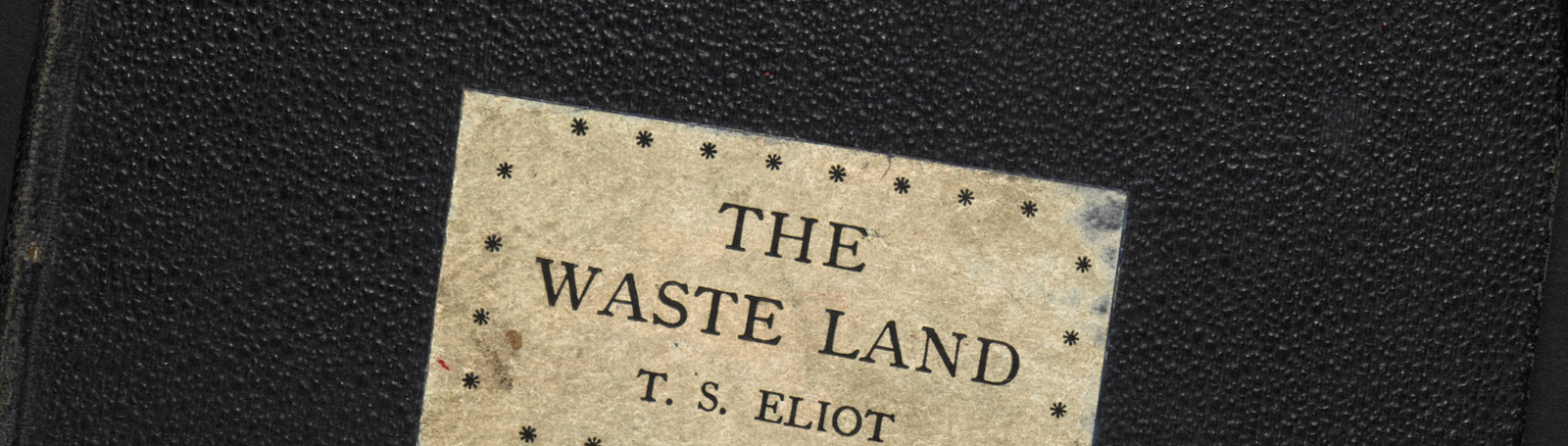

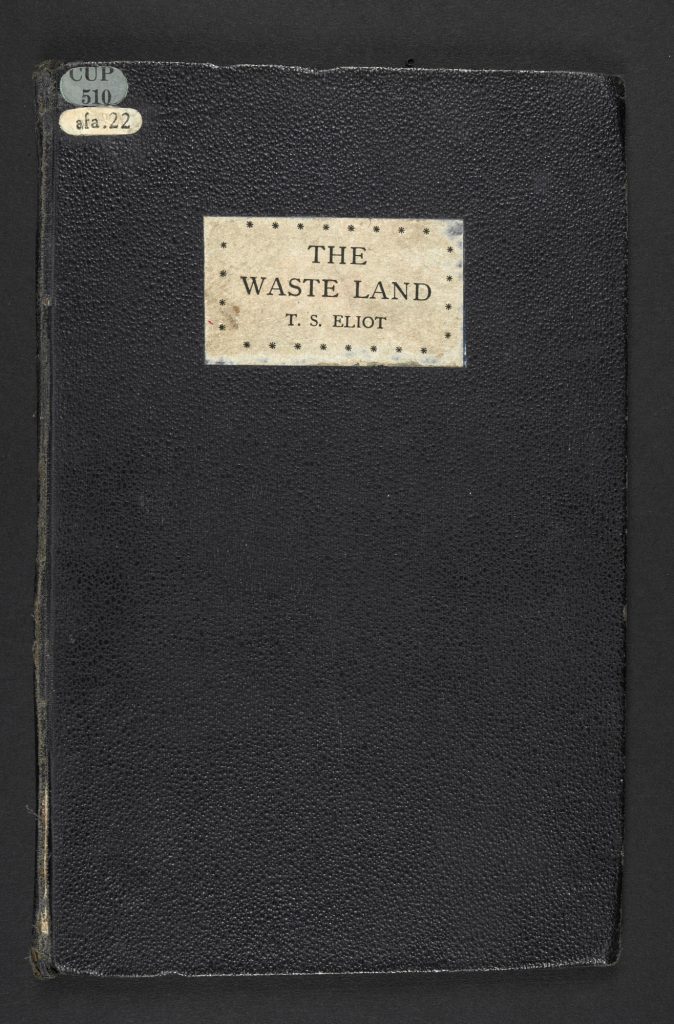

标题:The Waste Land by T S Eliot, 1923 Hogarth Press edition

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.510.afa.22.

版权:© Estate of T. S. Eliot. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

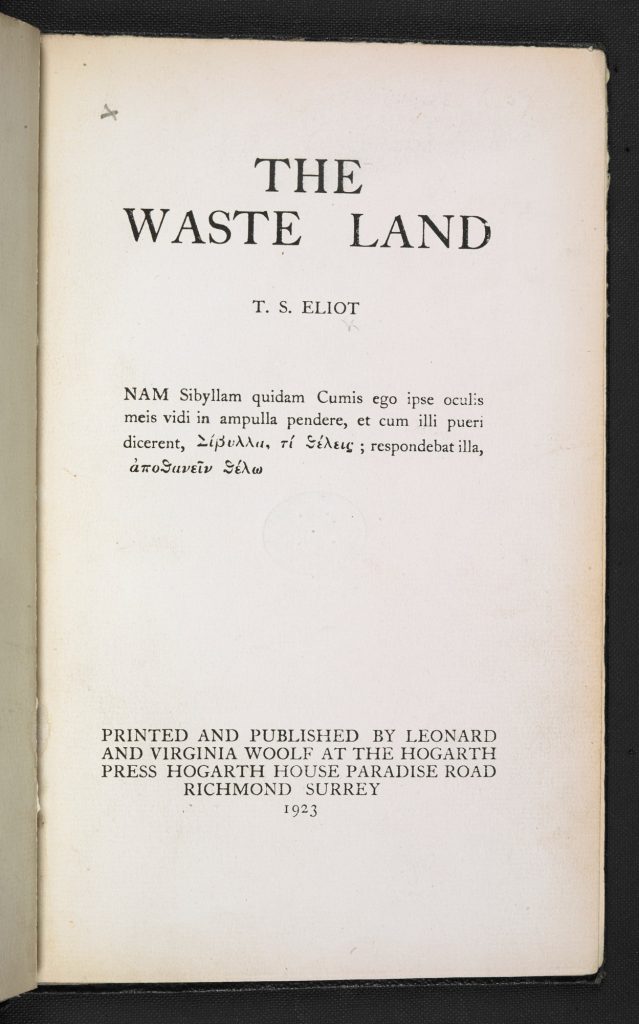

标题:The Waste Land by T S Eliot, 1923 Hogarth Press edition

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:Cup.401.F.15.

版权:© Estate of T. S. Eliot. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work.

<前页

后页>

A poem with many voices

Rather than a single dramatic monologue, like ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ (1915), woven throughout The Waste Land is a rich array of voices. There are numerous literary and cultural references from sources as diverse as Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Blake, Conrad, ancient Sanskrit and even soldiers’ trench slang from the First World War. In addition, the poem contains a variety of musical allusions: Wagner, music hall, ragtime and nursery rhyme; and these sit alongside the simple sounds of children sledging, horns and motor cars, pub chatter and the rattle of bones.

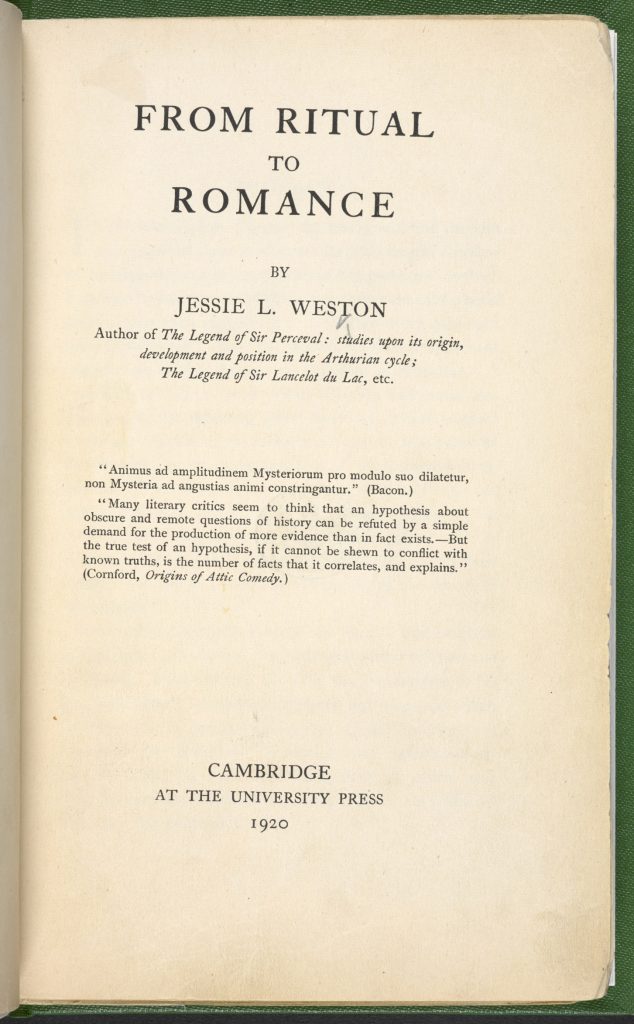

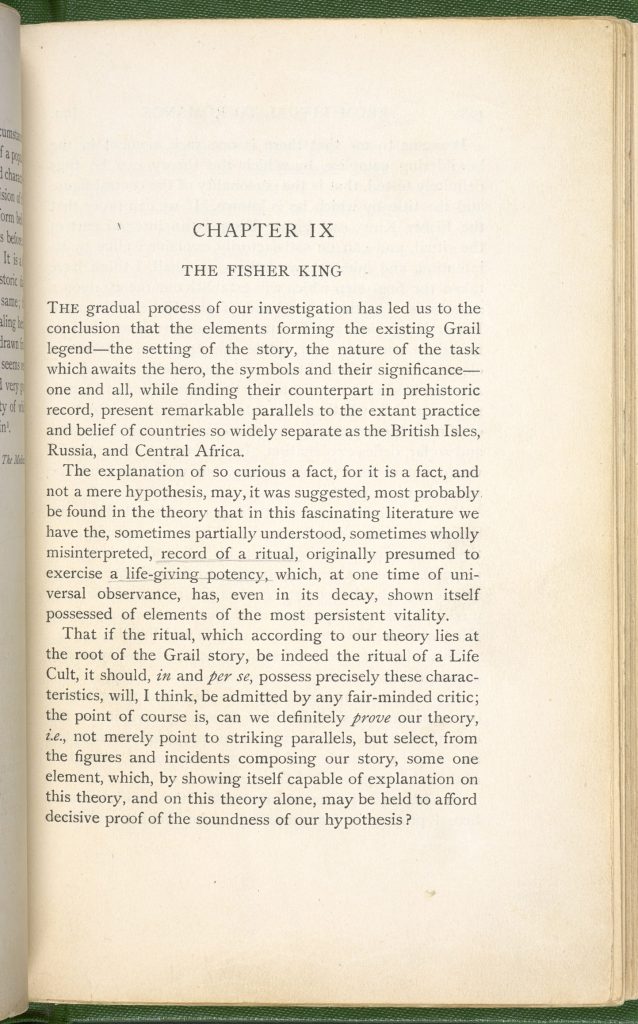

For many commentators, The Waste Land expresses disillusionment with 20th-century civilisation set against allusions to ancient myth, folklore and the Bible. In his notes , Eliot describes his indebtedness to Jessie L Weston’s book From Ritual to Romance on the legend of the Holy Grail, and it was this work that Eliot cites for the plan and much of the symbolism found in the poem.

标题:From Ritual to Romance

作者/创作者:Jessie Laidlay Walton

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:12403.bb.5.

版权:Public Domain

标题:From Ritual to Romance

作者/创作者:Jessie Laidlay Walton

藏品存于:British Library

书架号:12403.bb.5.

版权:Public Domain

<前页

后页>

The Waste Land was written in the aftermath of the First World War and has been interpreted as reflecting the plight of the generation left to confront a futile and confusing world. The majority of the poem was written at a time when Eliot was recovering from a nervous breakdown and was trapped in an unhappy marriage, leading some to consider the poem as autobiographical. Neither of these views was wholly accepted by Eliot, who commented that some critics were perhaps projecting their own disillusionment onto the work.

Looking back, Eliot felt that the poem ultimately overshadowed his other work, and described it not so much as ‘an important bit of social criticism’ but as ‘the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life; it is just a piece of rhythmical grumbling’. These rhythms are indeed intensely of the time, and include hints of jazz and popular song.

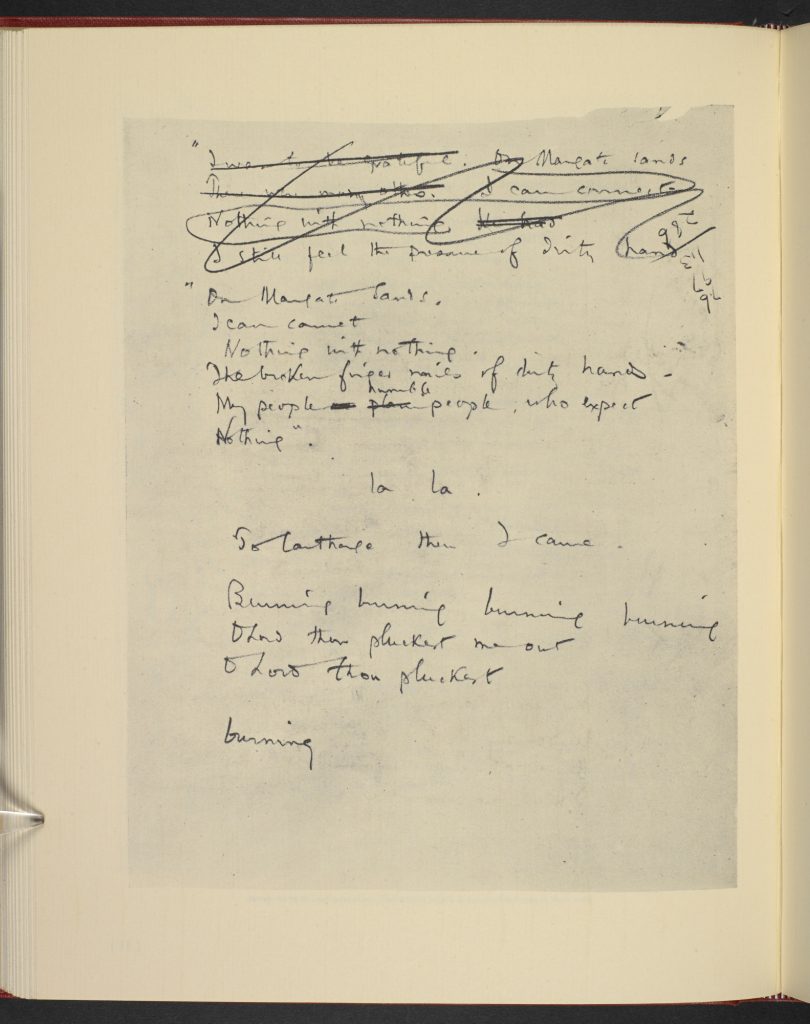

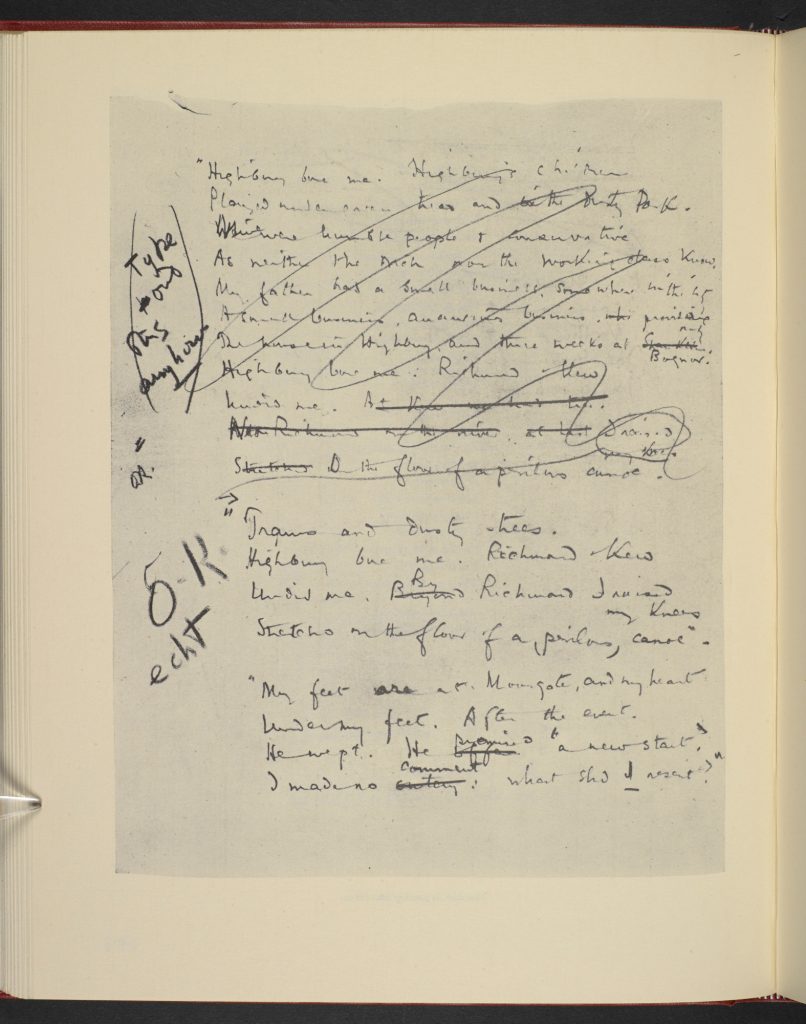

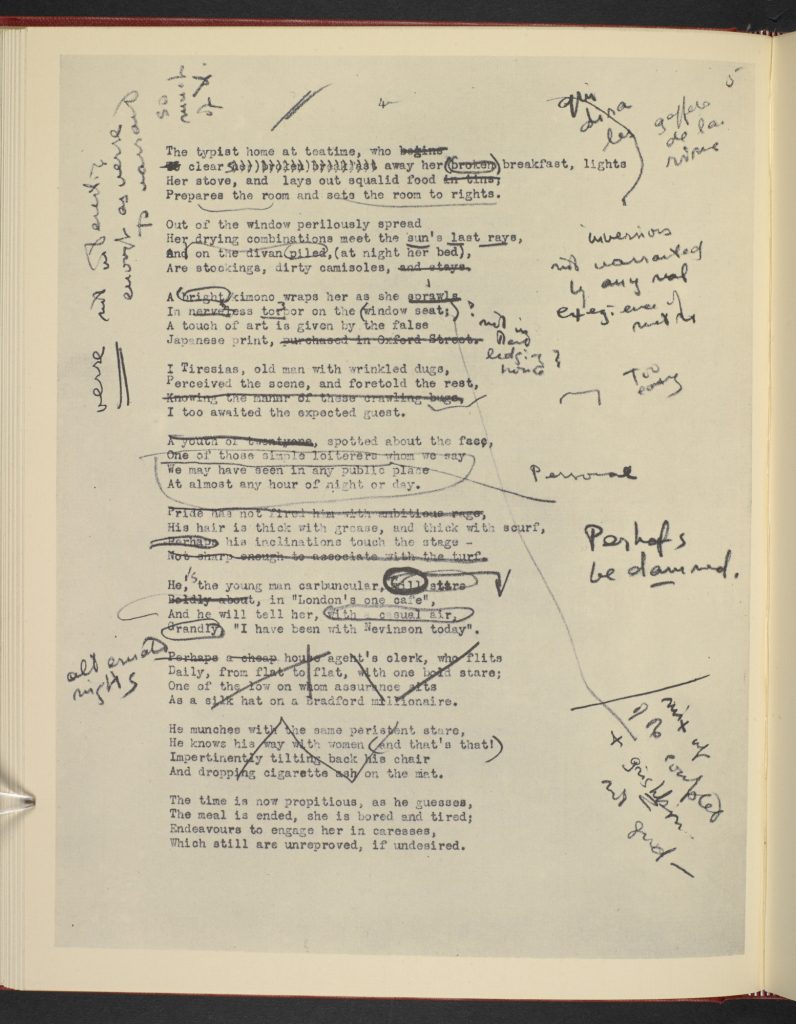

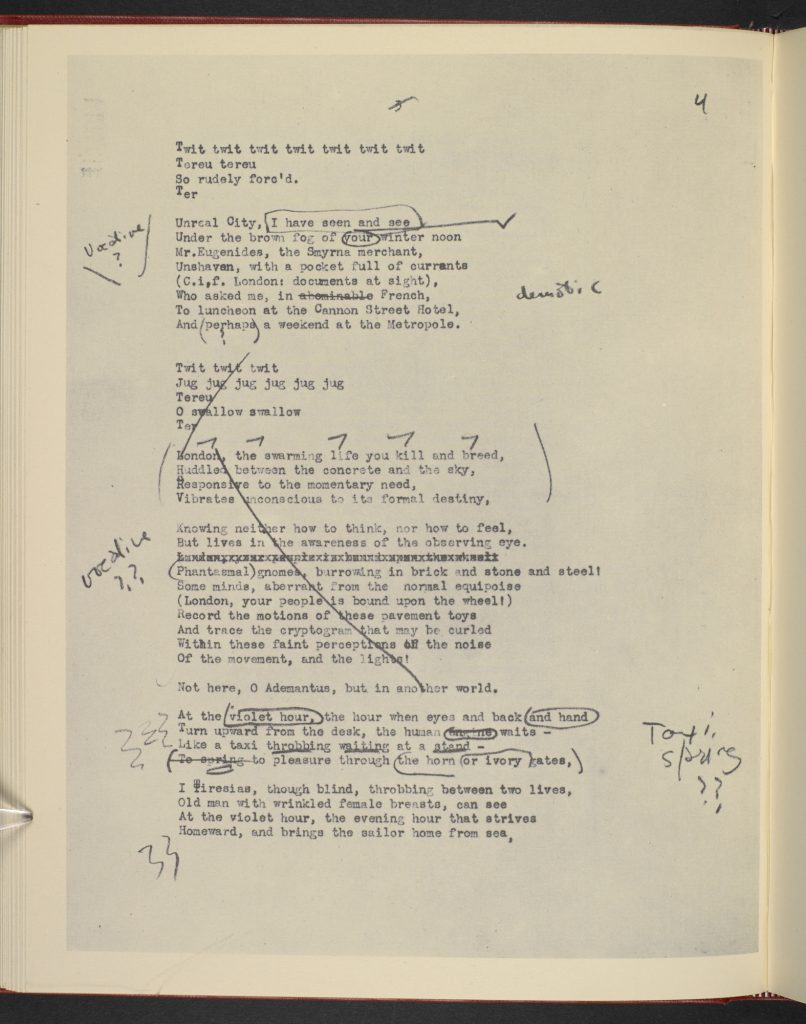

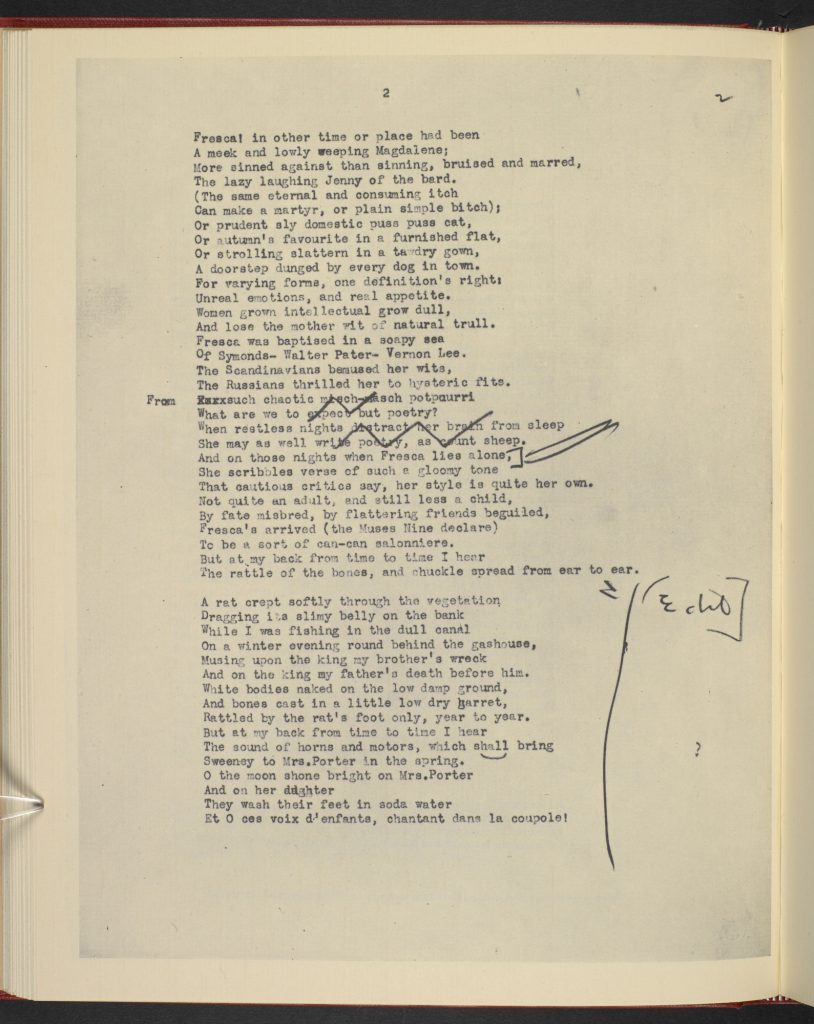

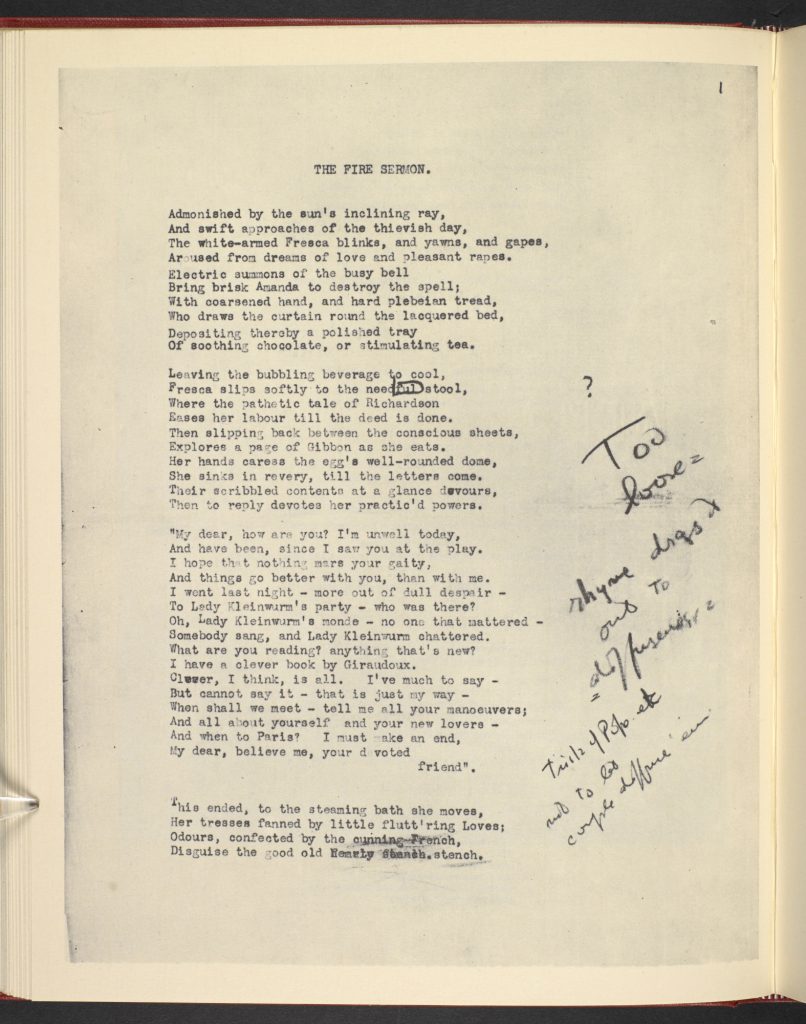

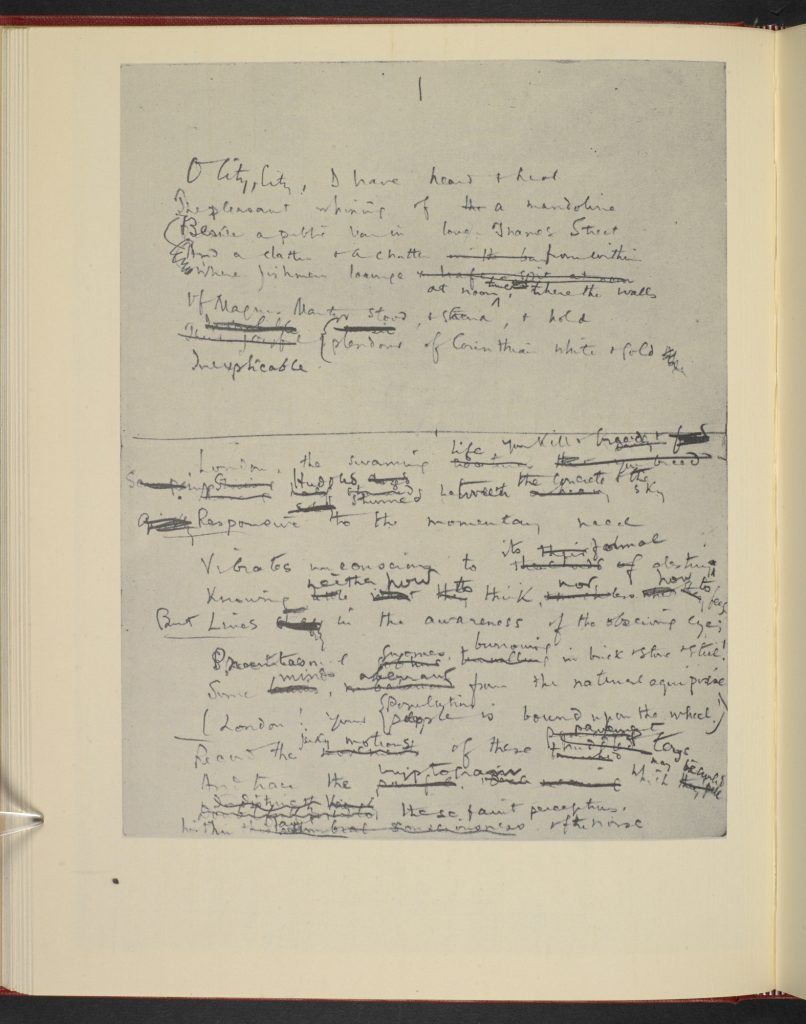

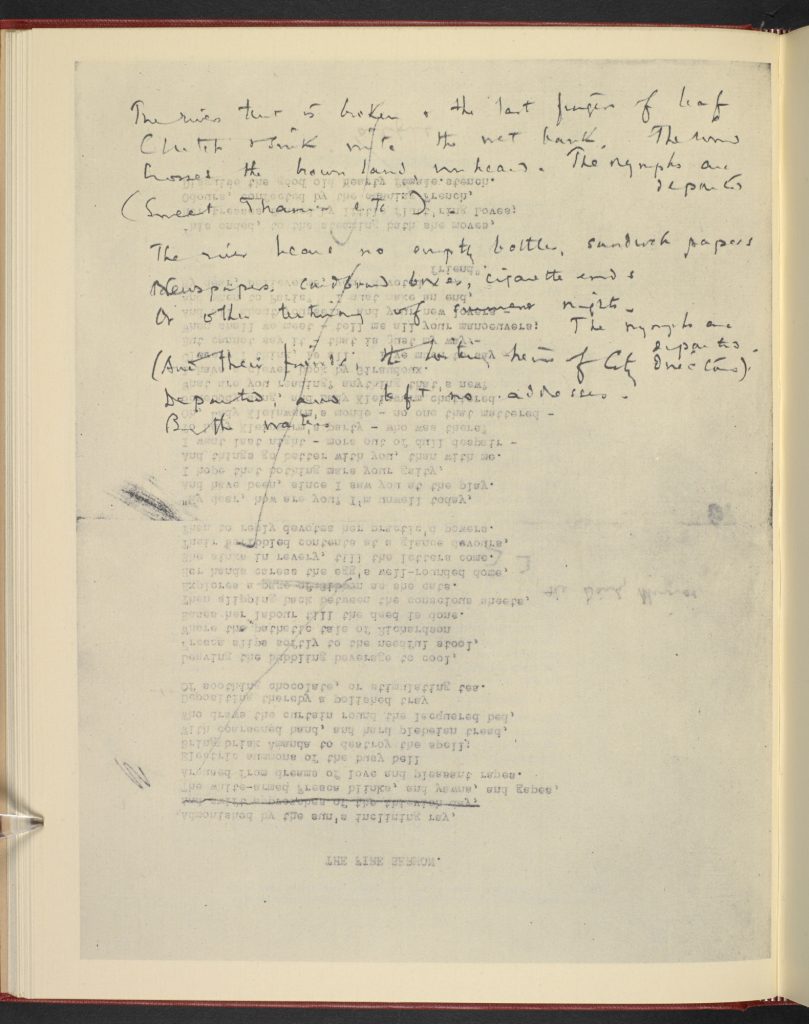

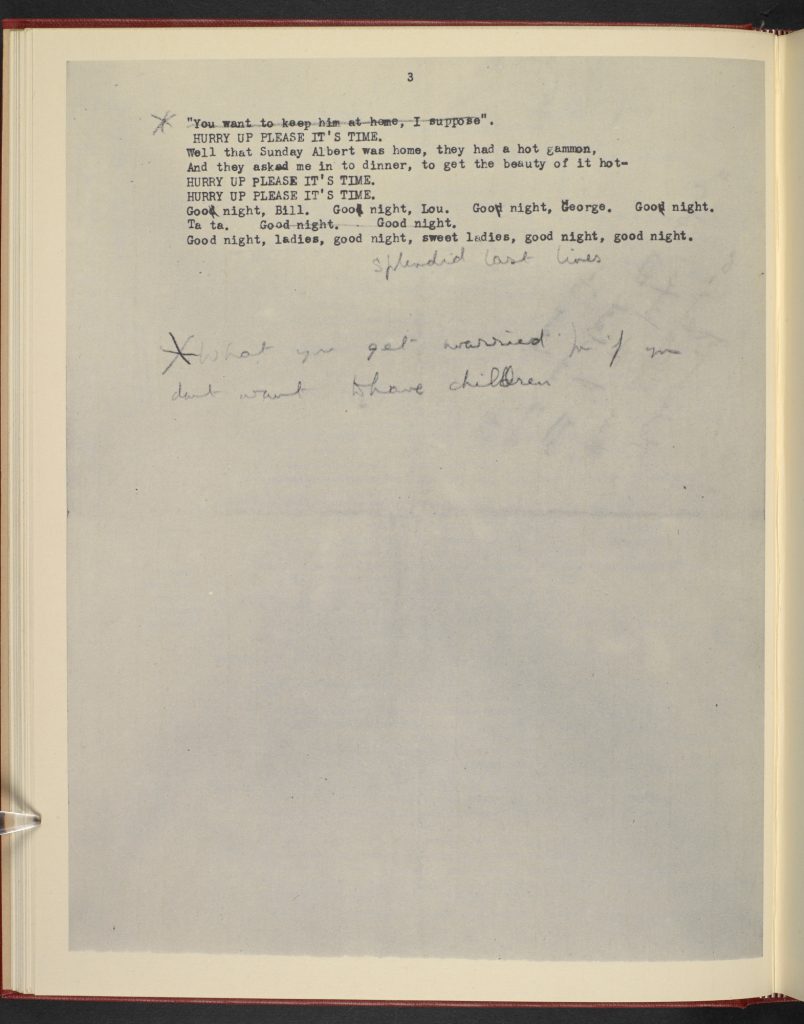

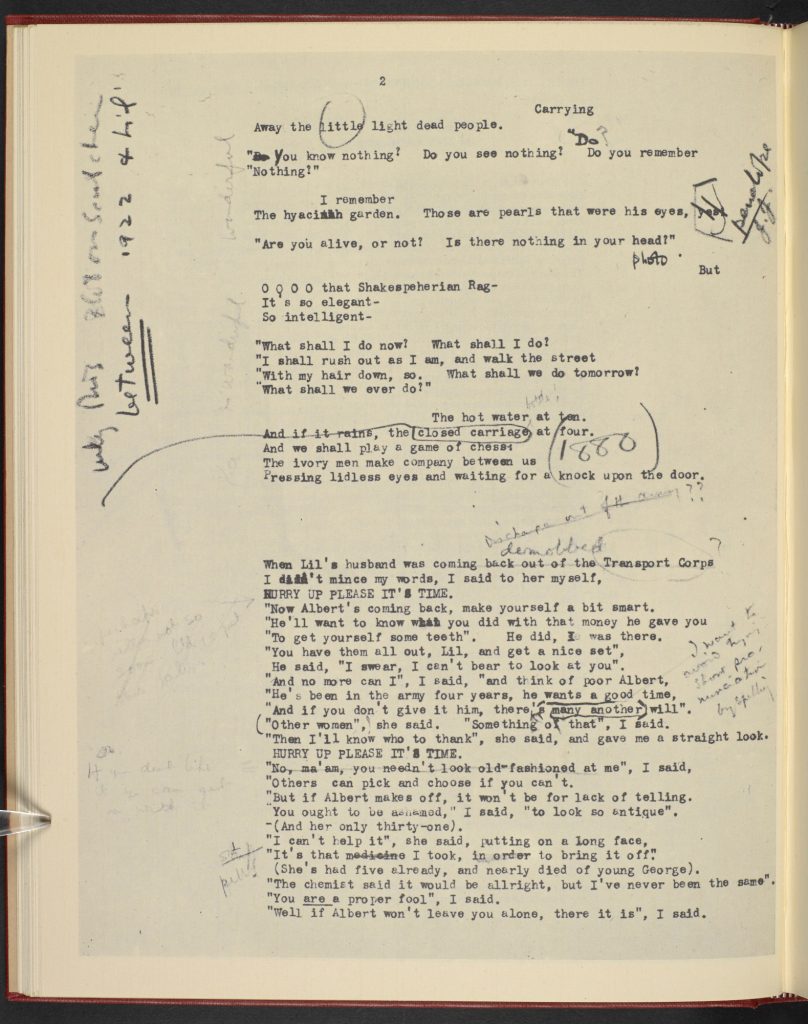

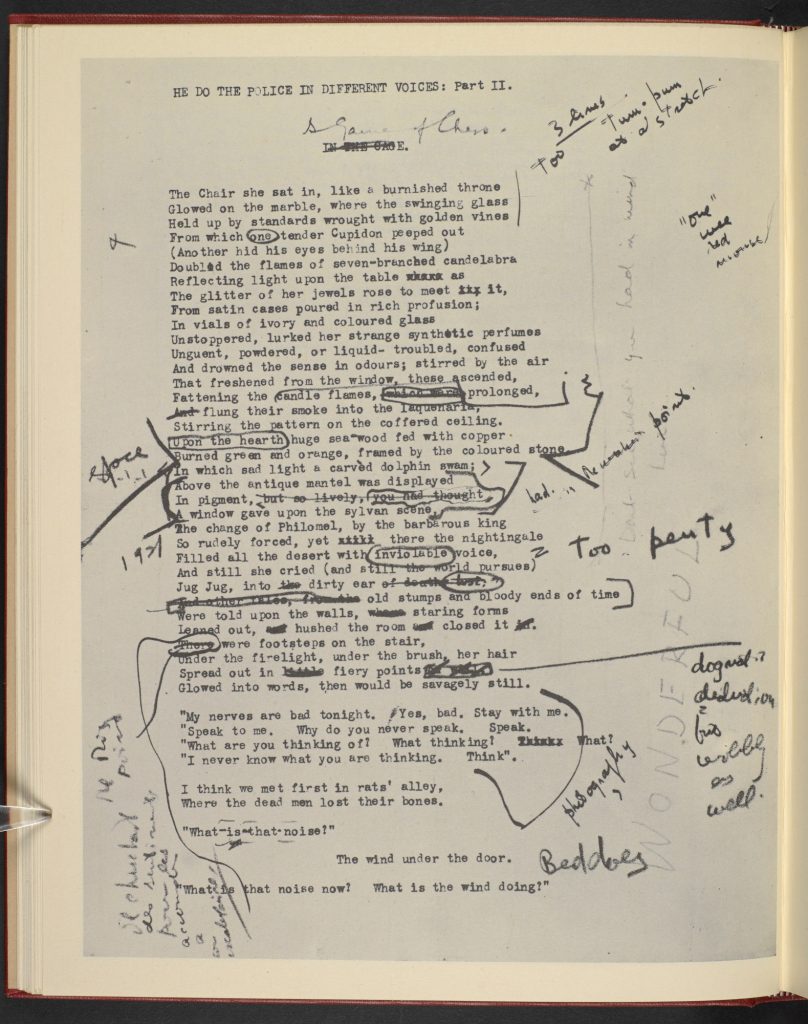

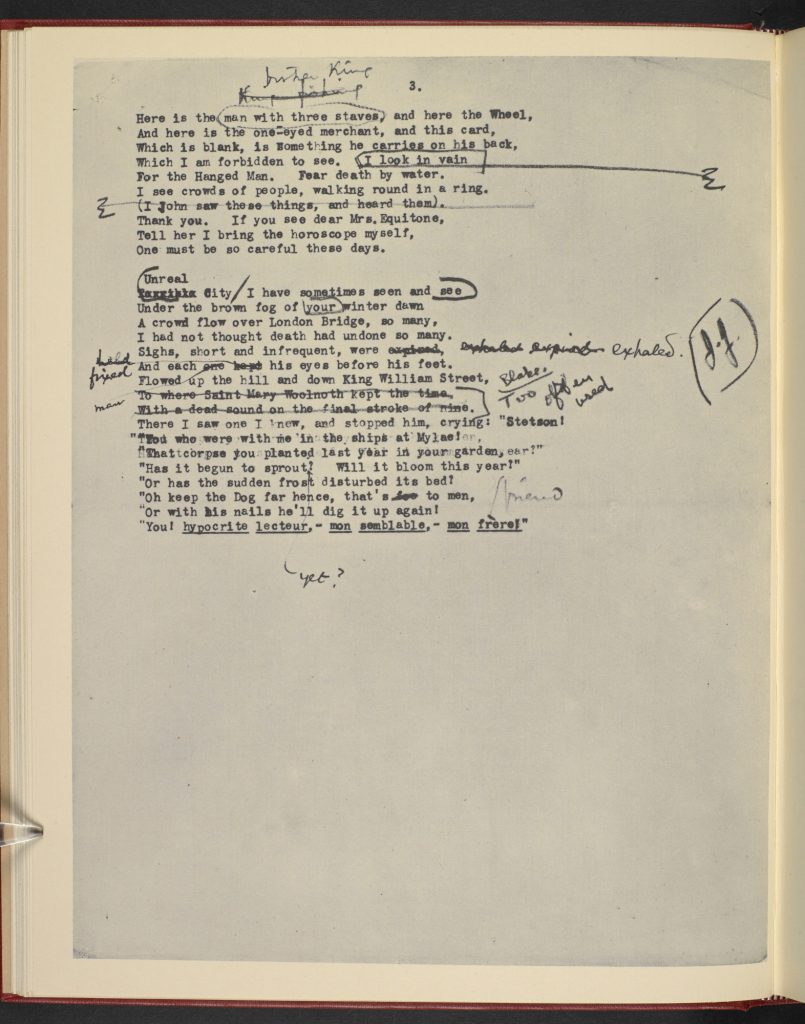

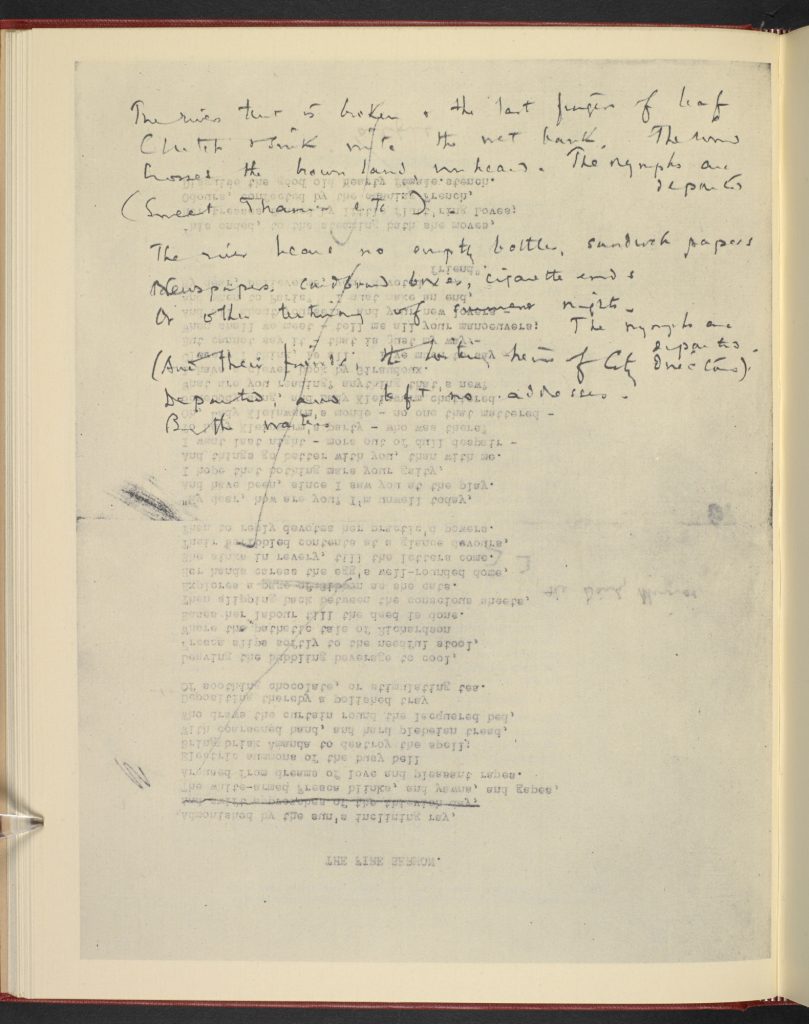

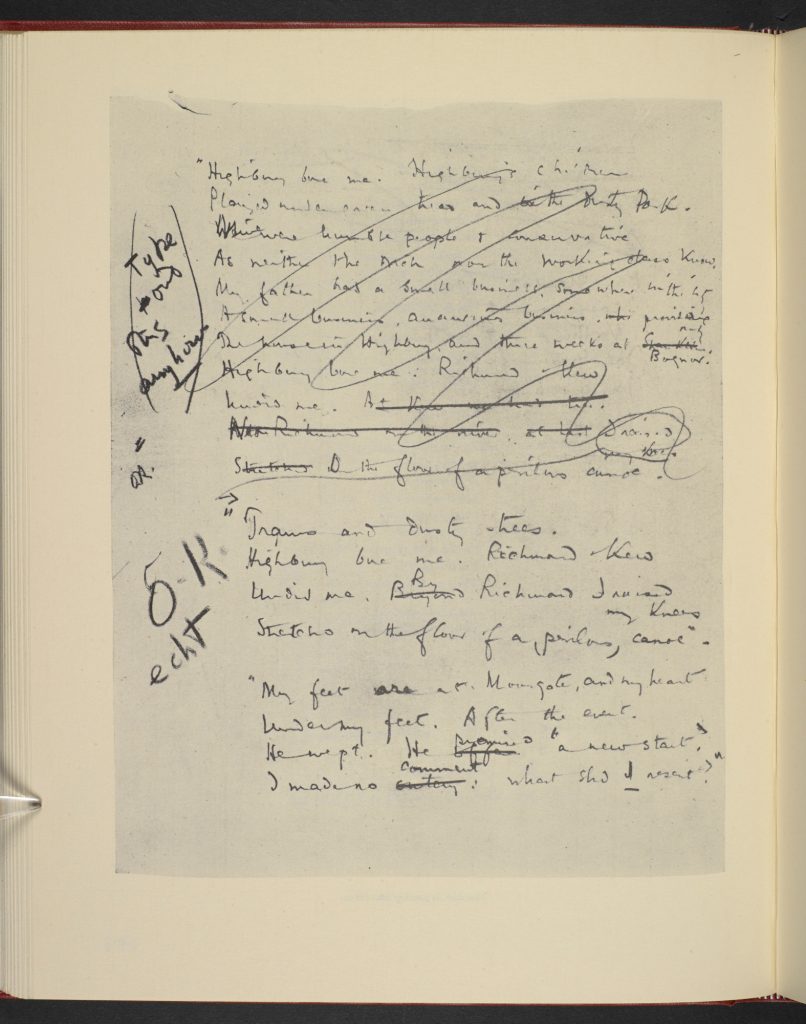

What does the manuscript tell us about how the poem took shape?

After straining one of his hands rowing while at graduate school, Eliot preferred to write by using a typewriter where possible. One example of where it was probably not possible would be in the shelter at Margate. Editors assume that most of the actual manuscript Eliot produced in Margate was destroyed. In this copy, on page 52, we can see him redrafting the closing parts of Part III, ‘The Fire Sermon’, with its lines:

On Margate Sands.

I can connect

Nothing with nothing.

(ll. 300–02)

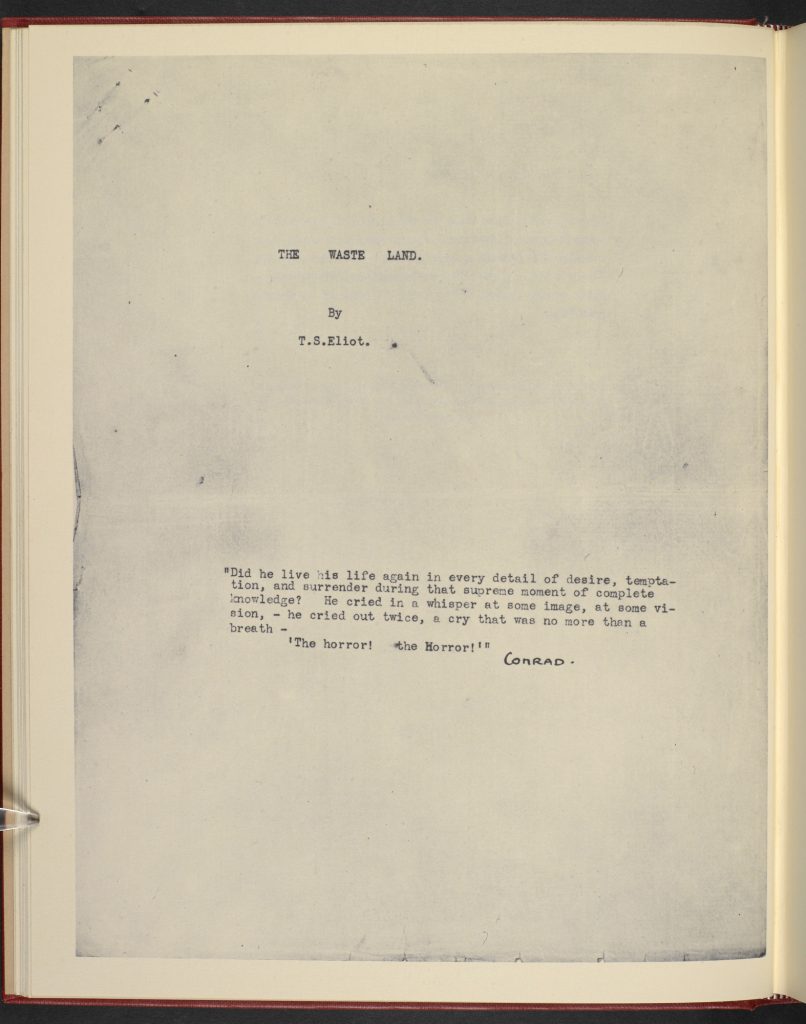

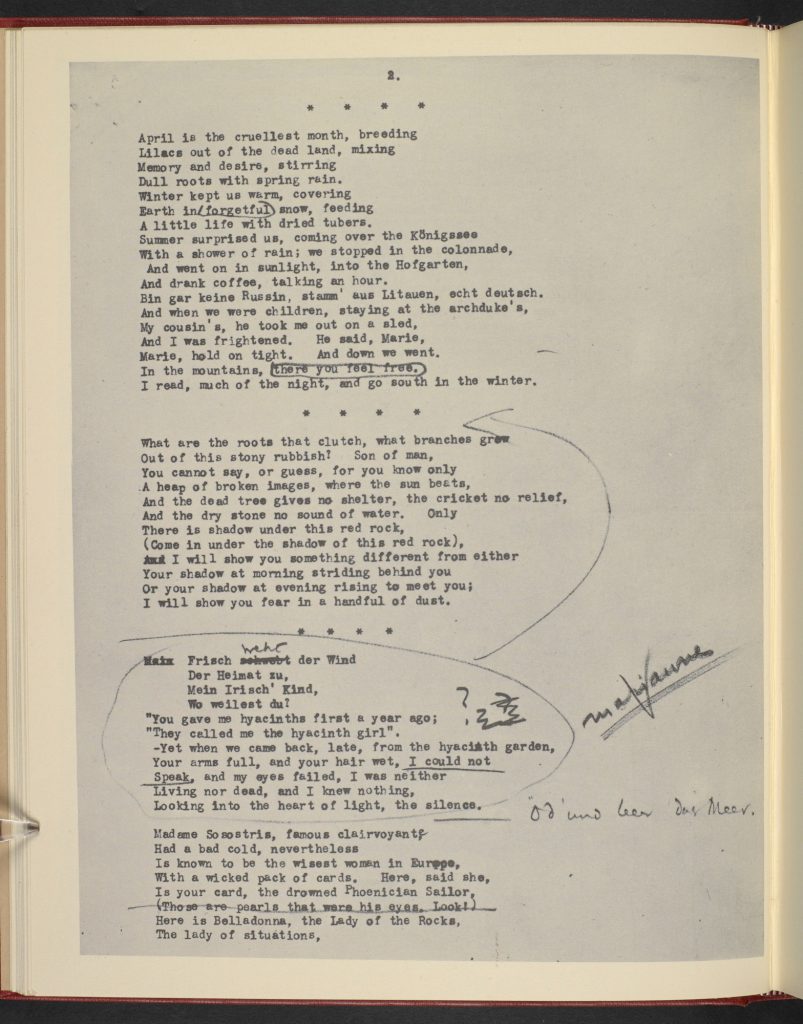

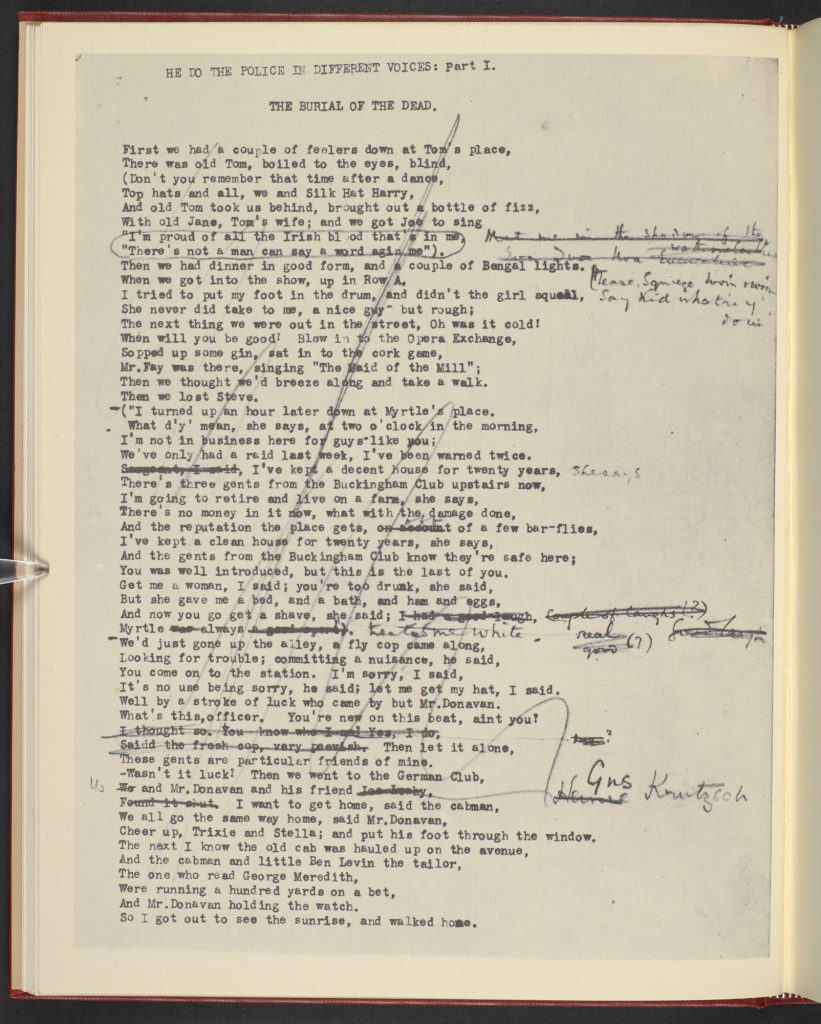

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权: T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

<前页

后页>

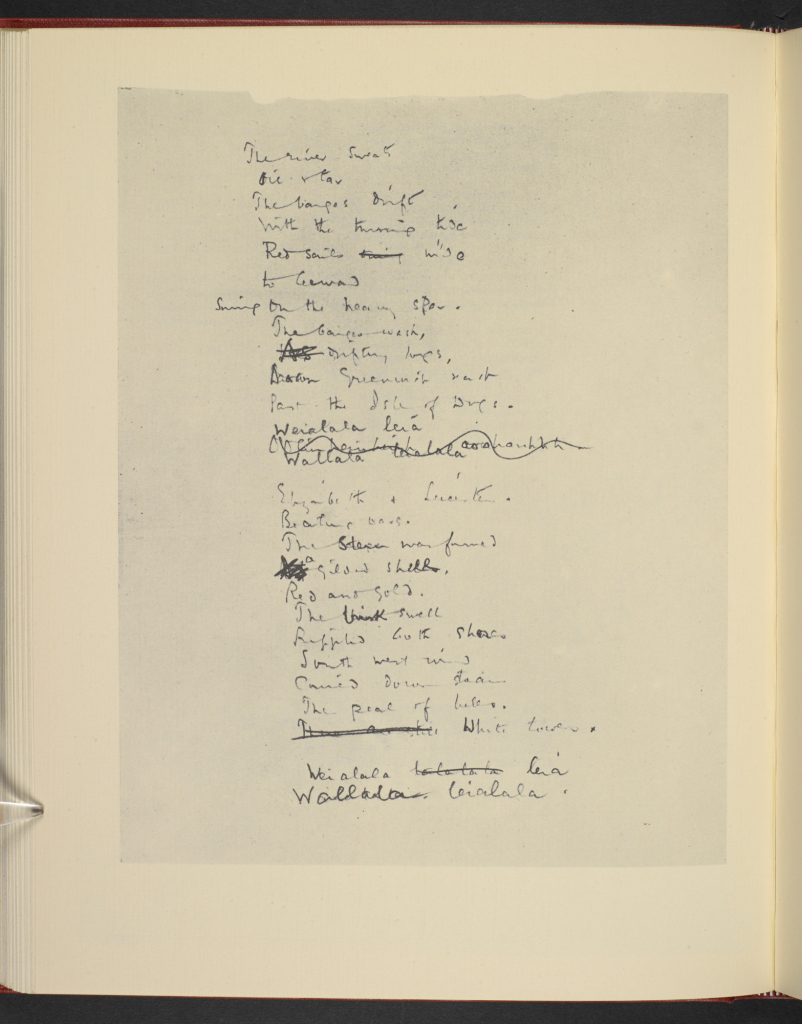

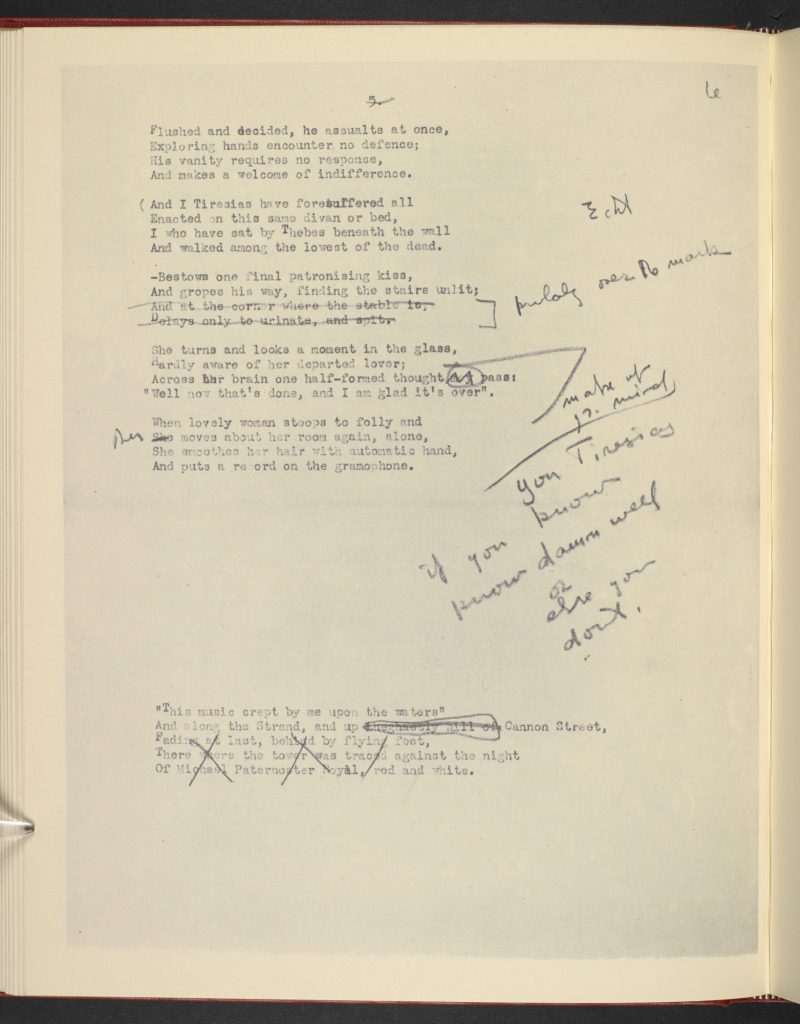

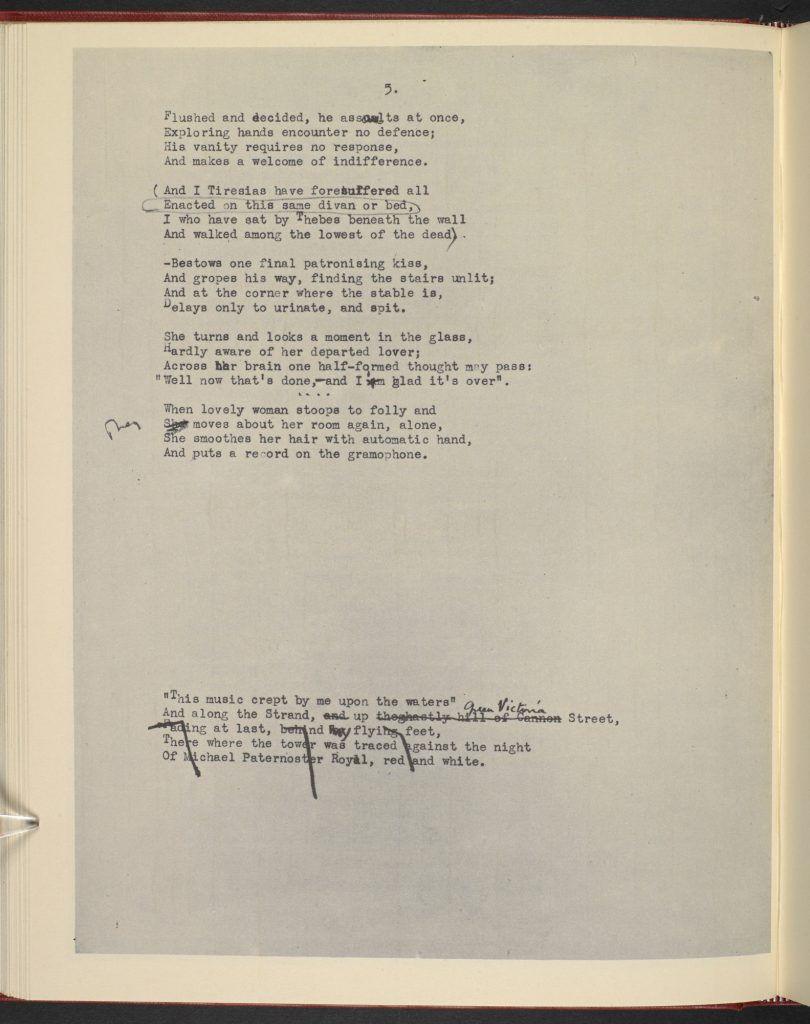

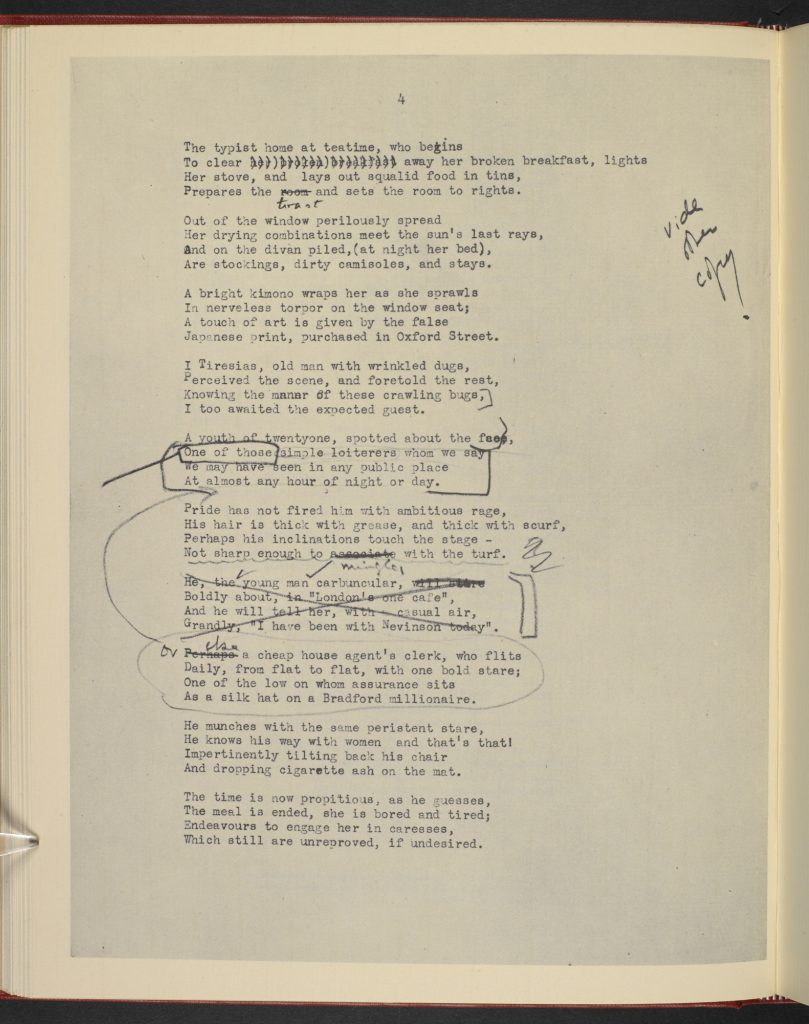

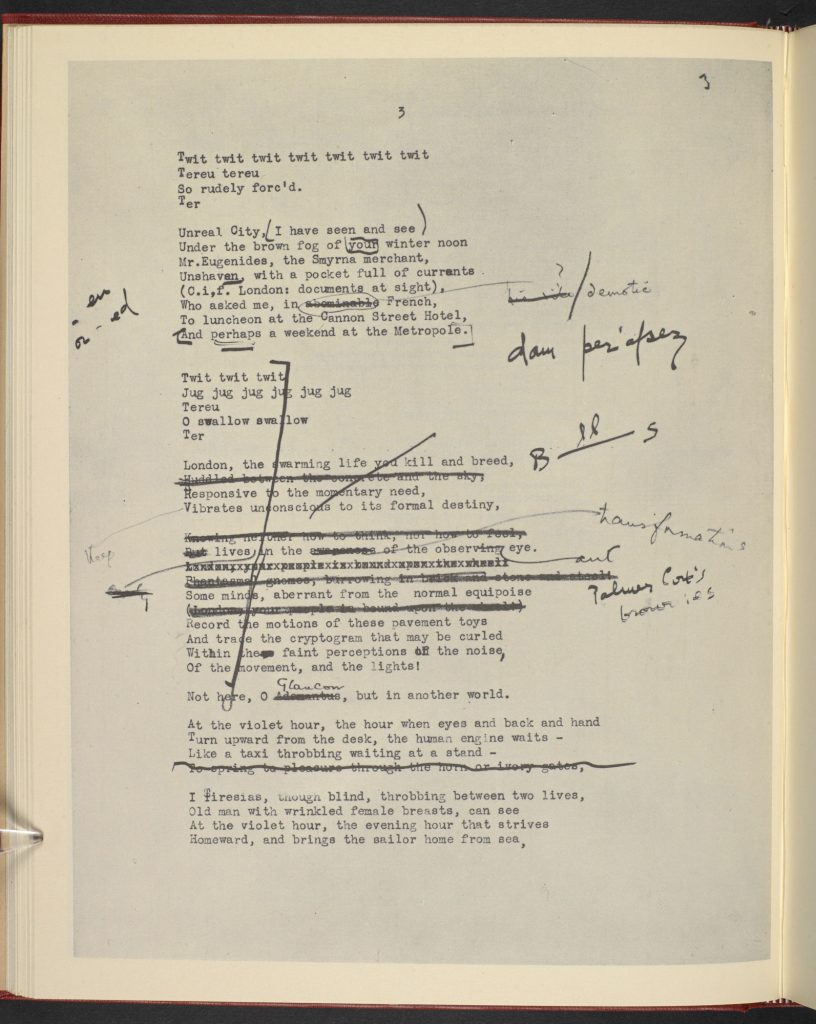

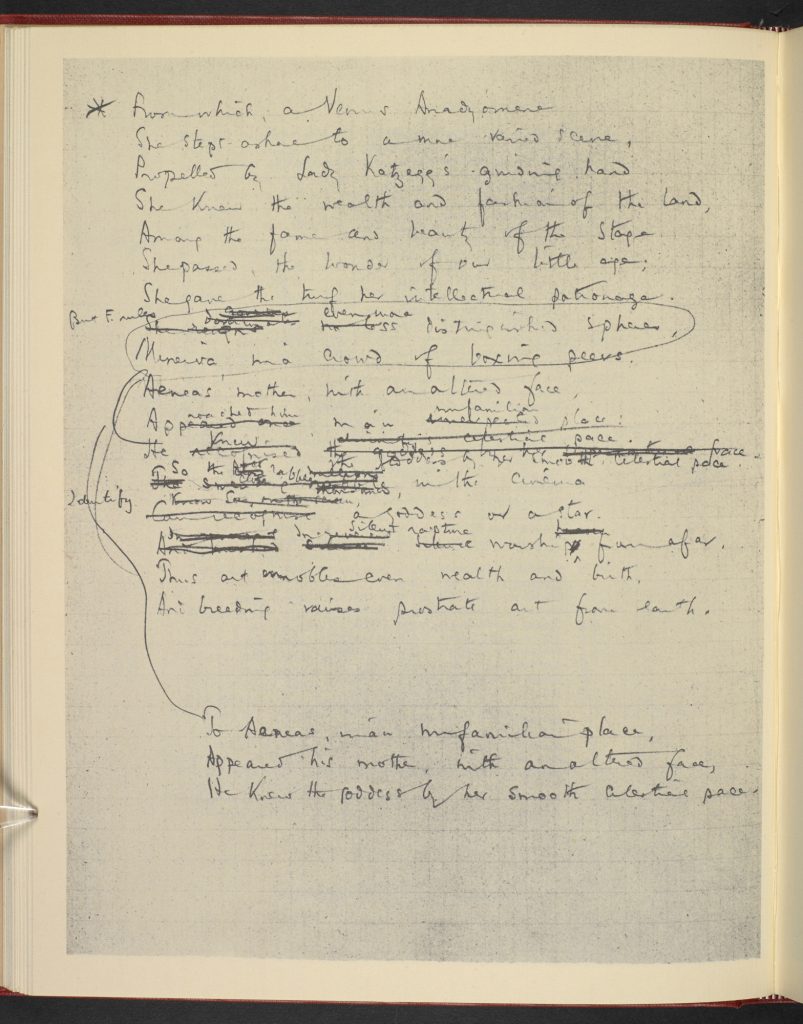

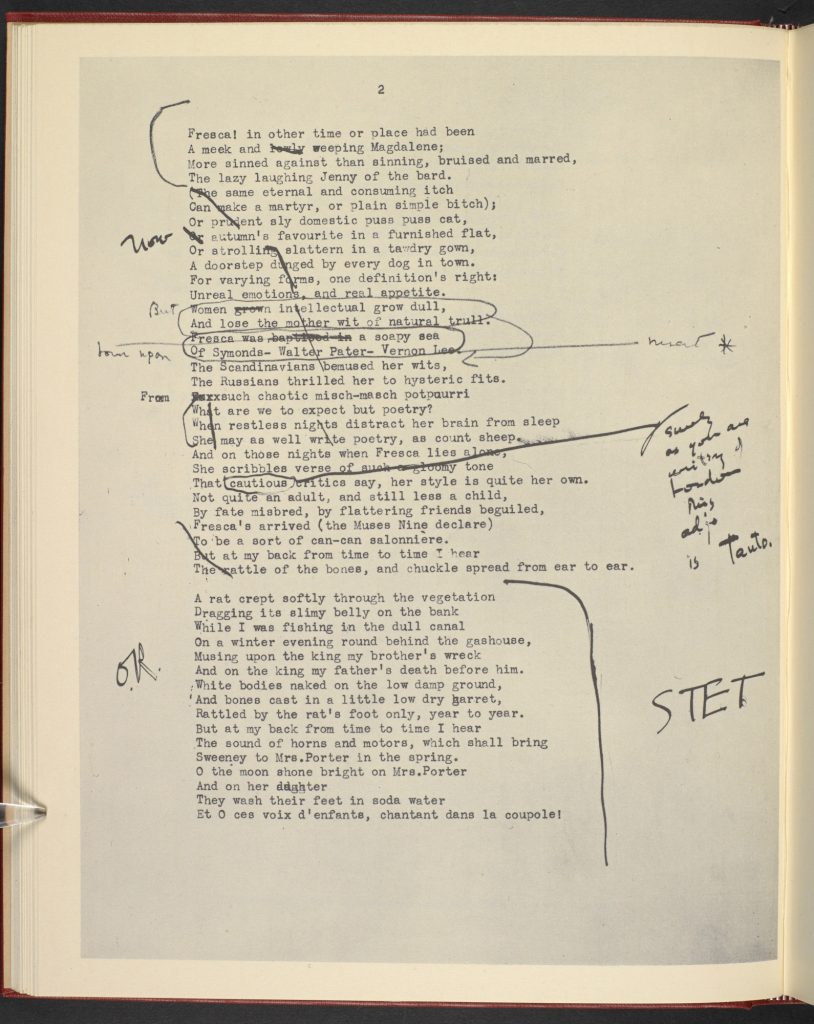

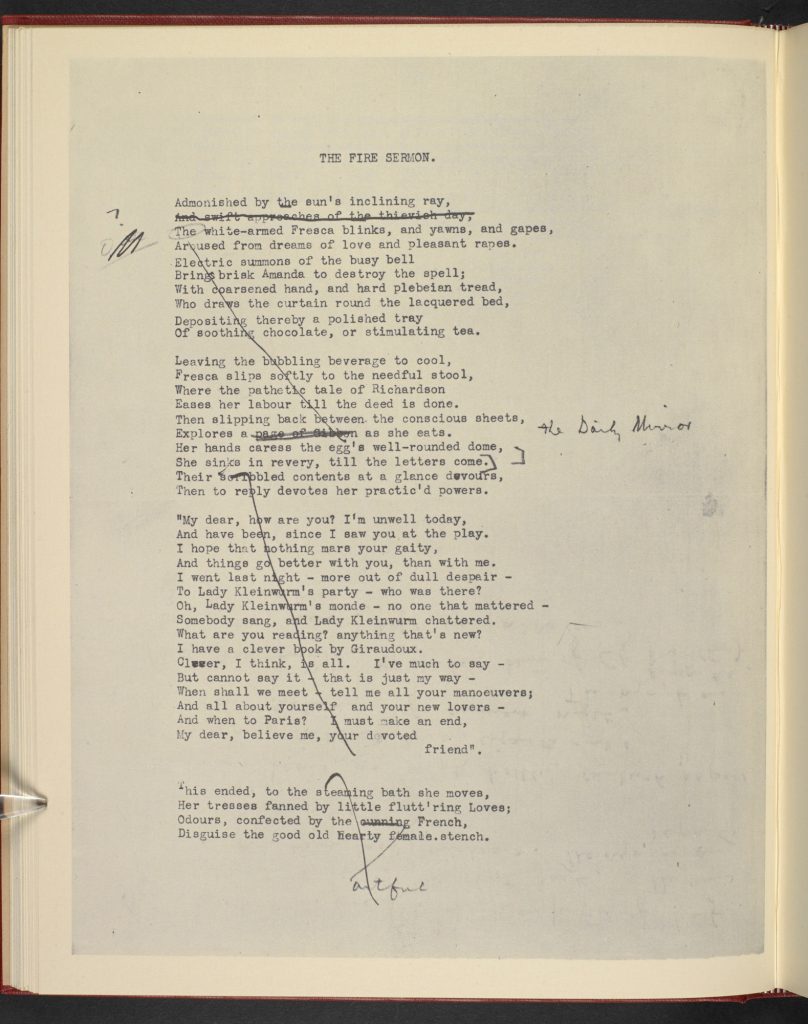

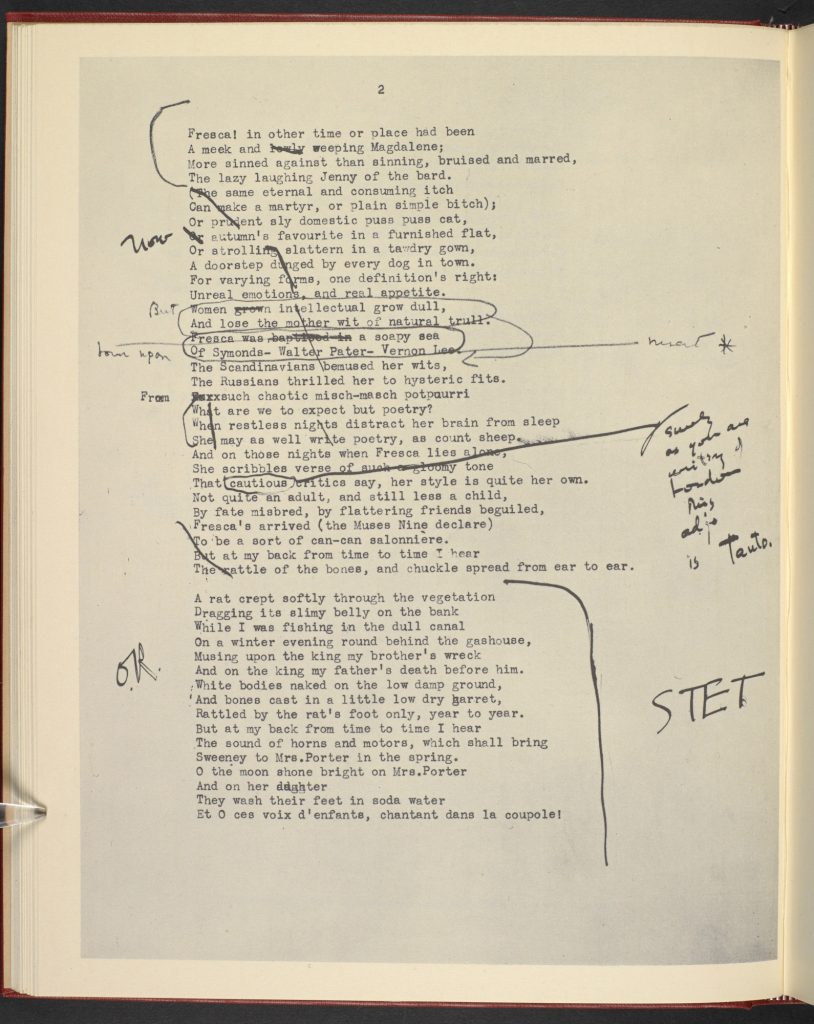

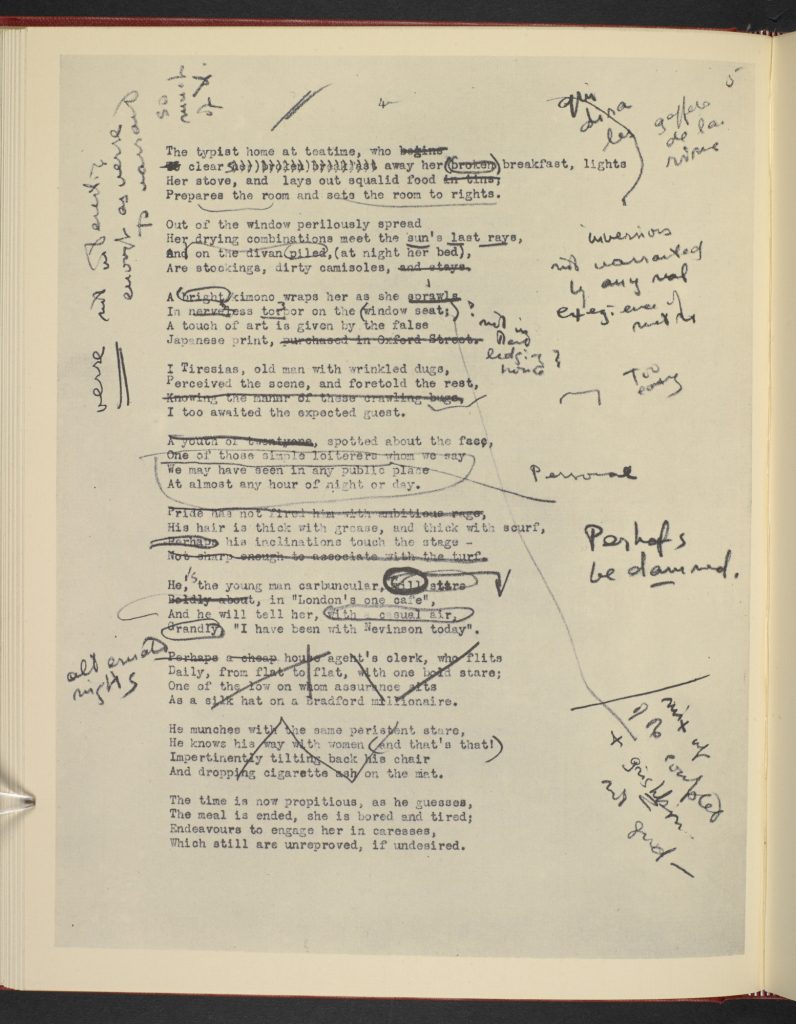

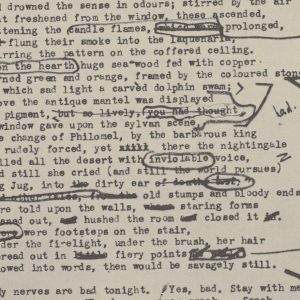

At the top of this manuscript, corrections, suggestions and comments have been added to the text by hand. In some instances, these are by Eliot’s wife Vivienne. The majority , however, are by the poet Ezra Pound, to whom Eliot showed the whole poem in Paris in January 1922. Critics have speculated that by this stage Eliot may already have decided to delete the first section of Part I, which describes a night out. But here in the draft, we can see them working together on the rest of this section. The two men worked particularly hard on Part III, ‘The Fire Sermon’. Pound suggested deleting the first page-and-a-half. As can be seen on page 24, Eliot then redrafted it by hand, upside down on the back of the paper. Because he was reincorporating some lines he had already written, he could refer to these in shorthand. One example is ‘Sweet Thames etc.’

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

The real thing

As can be seen from this typescript, Pound’s annotations use the standard terminology of professional editing. On page 26, for example, he has used the editing term ‘STET’, which means ‘let it stand’ in Latin.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Other notes are in the highly idiosyncratic blend of languages in which Pound communicated, both in person and writing. For example, at various points he annotates the text with the German word ‘echt’, by which he means a compliment: ‘this is the real thing’. Pound continued to help Eliot with the poem after their period together in Paris, sending suggestions by letter.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

On 24 January, after Eliot had returned to London, Pound wrote to him with a lightly comic poem praising Eliot’s achievement. He also wrote, ‘complimenti, you bitch’, and suggested, among other things, that the quotation from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) which stands at the front of this manuscript should be removed.

The version printed later that year does indeed lack the Conrad quotation, a decision which Eliot apparently later regretted. It was replaced with a quote in Latin and Greek from the Satyricon, an ancient Roman novel attributed to Petronius.

标题:Manuscript of T S Eliot's The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

作者/创作者:T S Eliot

藏品存于:The Berg Collection, New York Public Library

书架号:Cup.410.g.63

版权:T S Eliot: © Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. Please credit the copyright holder when reusing this work. Ezra Pound: By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2015 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Except as otherwise permitted by your national copyright laws this material may not be copied or distributed further. Berg Collection: © The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature The New York Public Library Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

In recognition of his editorial work, Eliot also included a dedication to Ezra Pound: ‘il miglior fabbro‘. This is a slightly altered quotation from the Purgatorio, the second part of The Divine Comedy (c. 1309–20). In three parts, this epic poem by the medieval Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) describes a progression from Hell through Purgatory to Heaven. In the quotation, Dante is pointing at the poet Arnaut Daniel, and calling him ‘the better craftsman’. For some critics this is an allusion to the fact that Pound’s ‘craft’ is perhaps more obscure than Eliot’s; for others, it is straightforward praise and thanks.