Original manuscripts by five of the greatest writers in the English language will go on show in Shanghai for the first time in March 2018. ‘Where Great Writers Gather: Treasures of the British Library’ will feature drafts, correspondence and manuscripts by writers including Charlotte Brontë, D H Lawrence, Percy Bysshe Shelley, T S Eliot and Charles Dickens, alongside Chinese translations, adaptations and responses to their works.

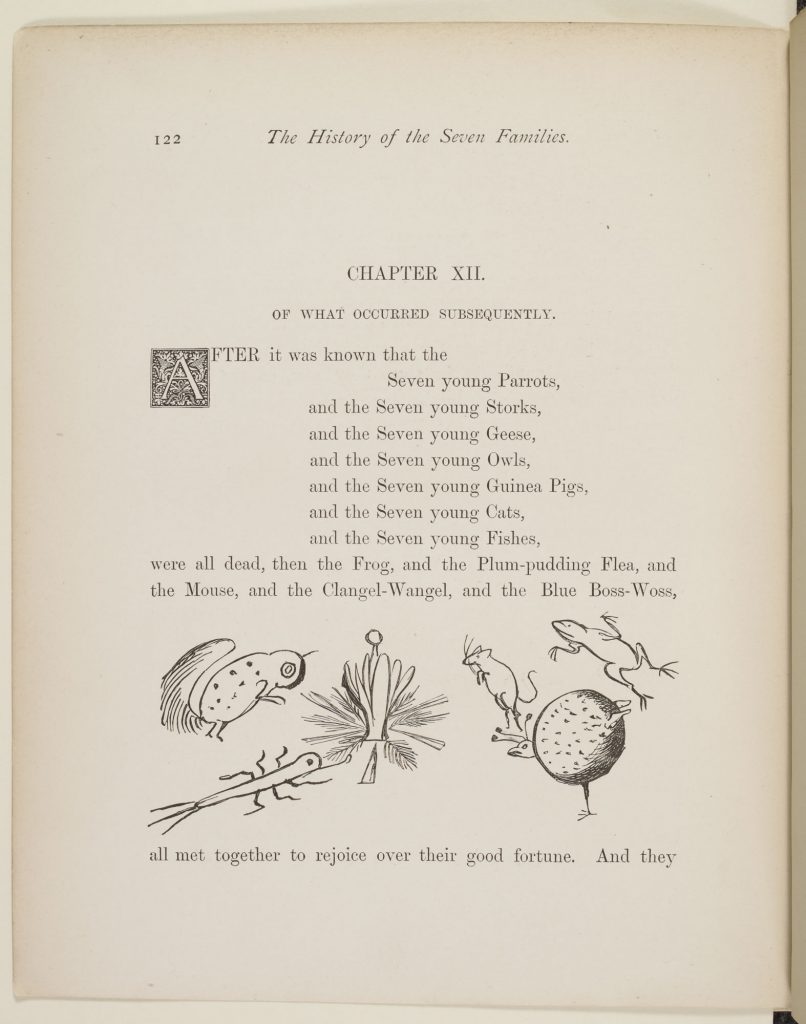

T S Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats

出版日期: 1939 文学时期: 20th century

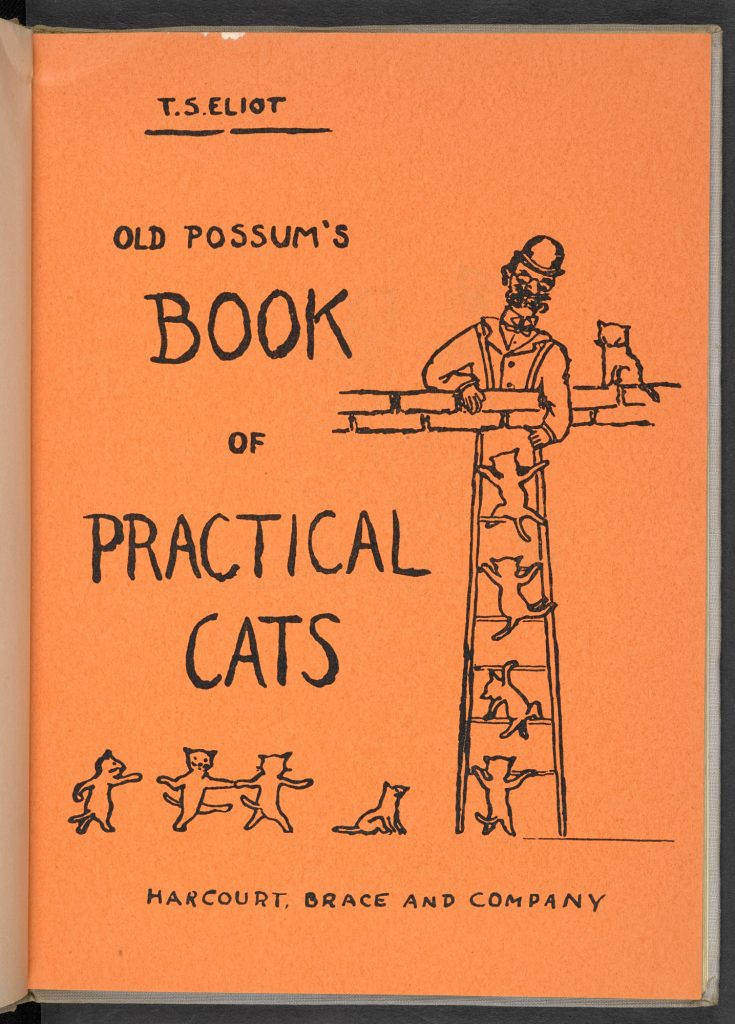

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats is a book of comic verse by the American modernist poet T S Eliot. The works contained are ‘nonsense’ poems in the tradition of Edward Lear, as well as passages of nursery rhyme and popular song.

T S Eliot

出生: 26 September 1888 逝世: 4 January 1965 职业: Poet, Playwright, Essayist, Critic, Publisher‘No biography’, instructed T S Eliot as he came to the end of his life in 1965. His prohibition was faithfully observed for decades and has only very recently been relaxed. Over those years his status as the leading modernist poet (in English) of the 20th century – and the greatness of his poem The Waste Land – was never challenged. But, ironically, the work of Eliot’s which sold best was a collection of ‘cat poems’ for children.

Eliot’s block on any posthumous biography was less the result of there being skeletons in his closet (cats to be let out of the bag, one might say) than his extreme, morbid almost, sense of privacy. He was, said Leonard Woolf (a close friend, as was his wife, Virginia), like someone in a sealed envelope.

None the less one can learn a lot about a person from their pets and the emotions they show them. Virginia Woolf, for example, was very much a ‘dog person’ and wrote one of the great canine novels in the English language, Flush: A Biography, in honour of another literary dog lover, Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Eliot was a ‘cat man’. He owned many during his life and gave them such fondly ridiculous names as Jellylorum, Pettipaws, Wiscus, and George Pushdragon. No one would call the cat, as they do the dog, ‘man’s best friend’. Their relation to humans is always wary and frankly selfish. It is clear that Eliot, like Michel de Montaigne, was fascinated by the dignified remoteness of his feline companions. Was he playing with his cat, wondered Montaigne, or was his cat playing with him?

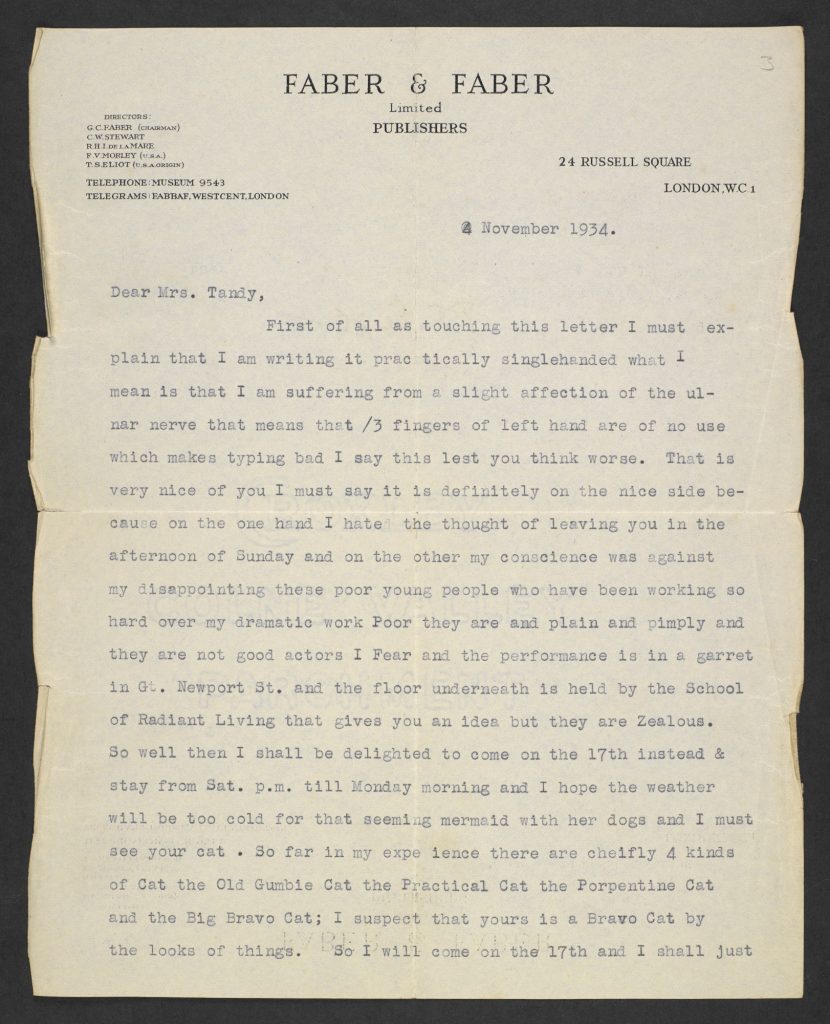

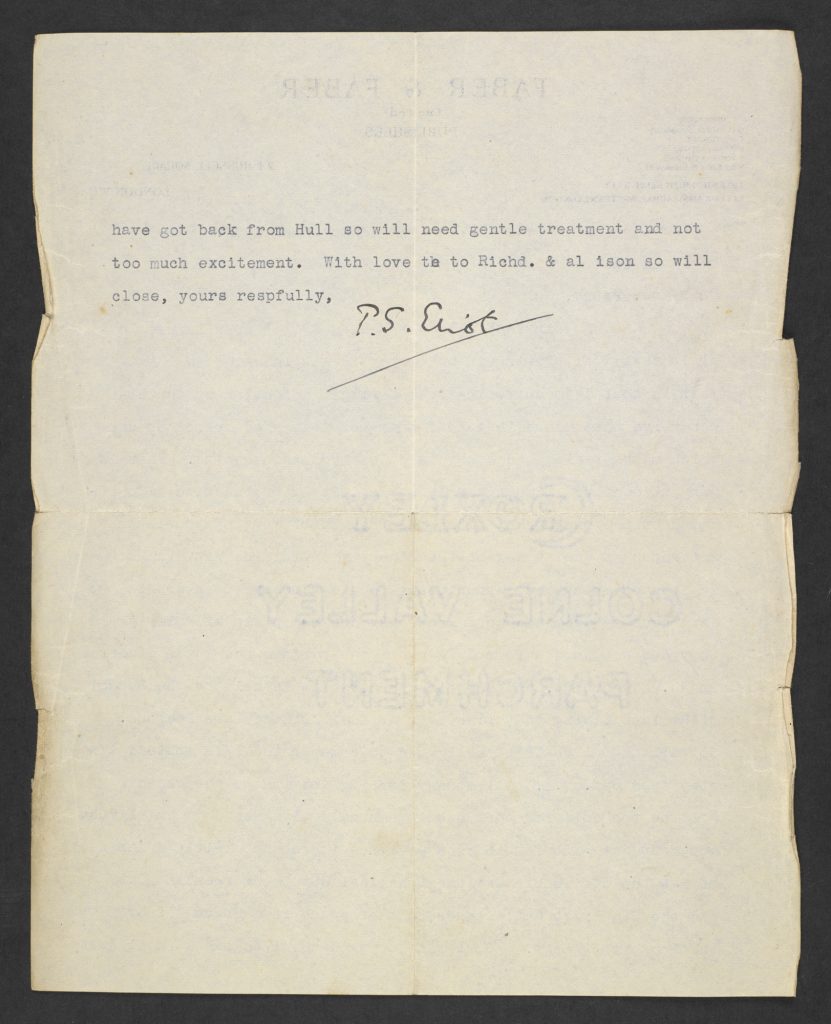

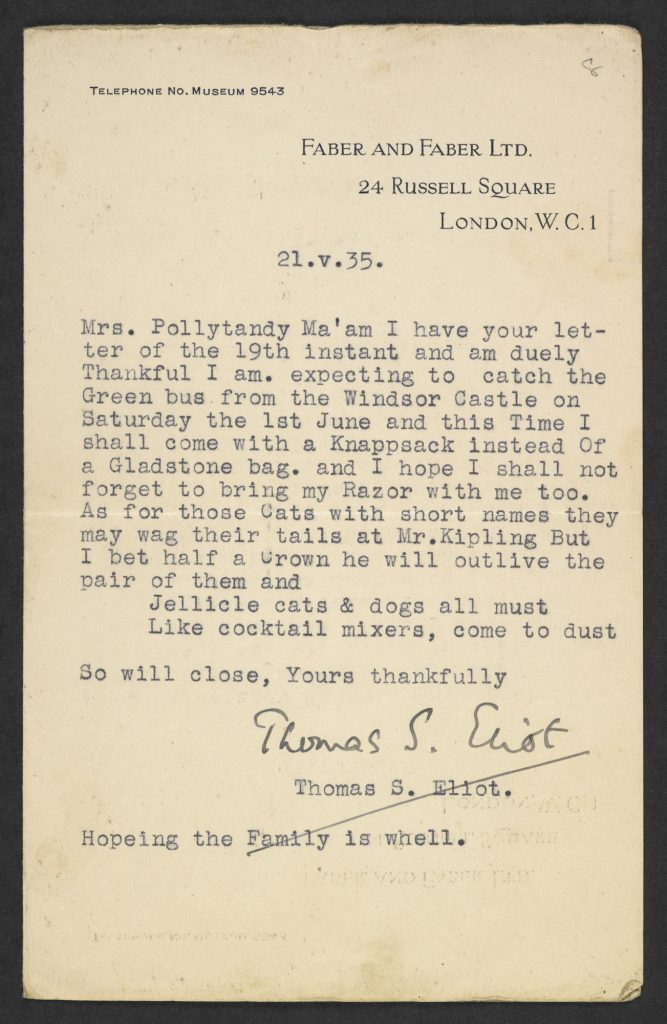

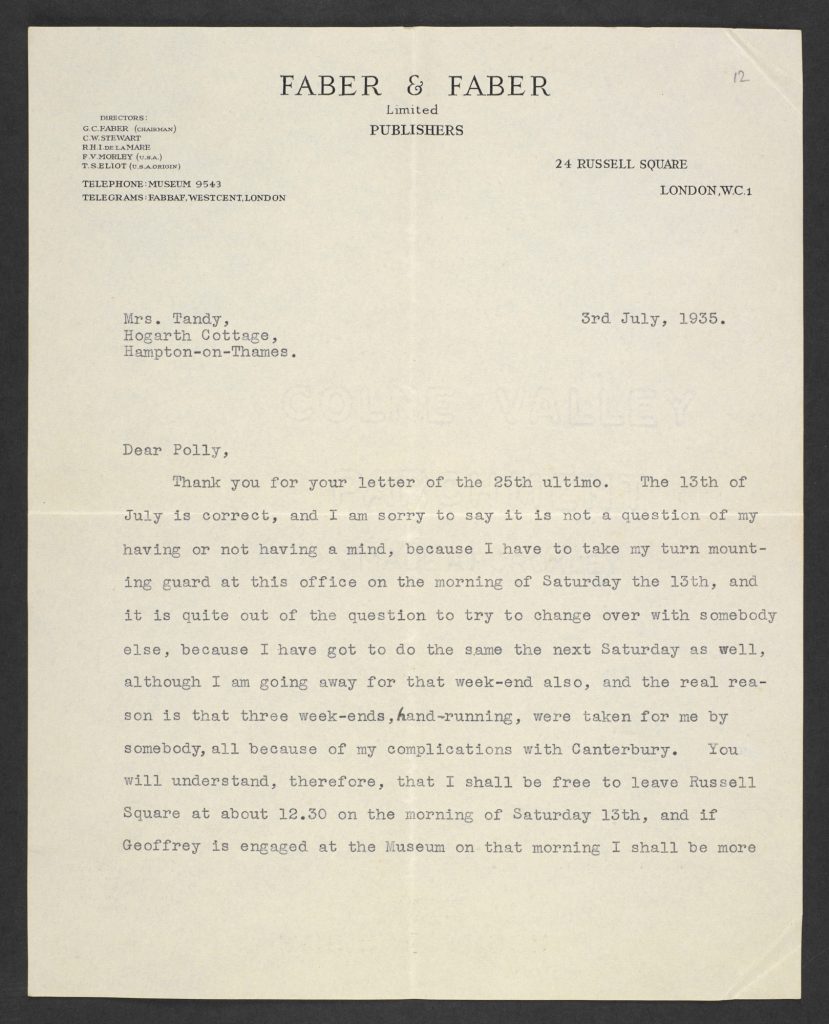

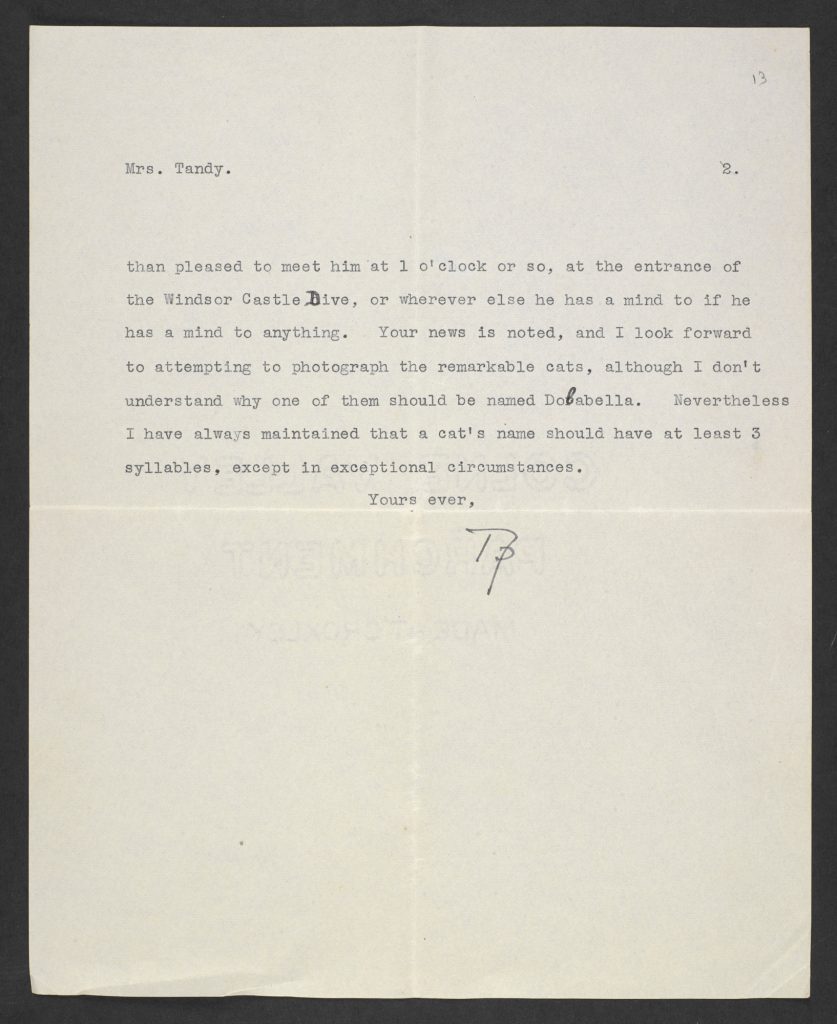

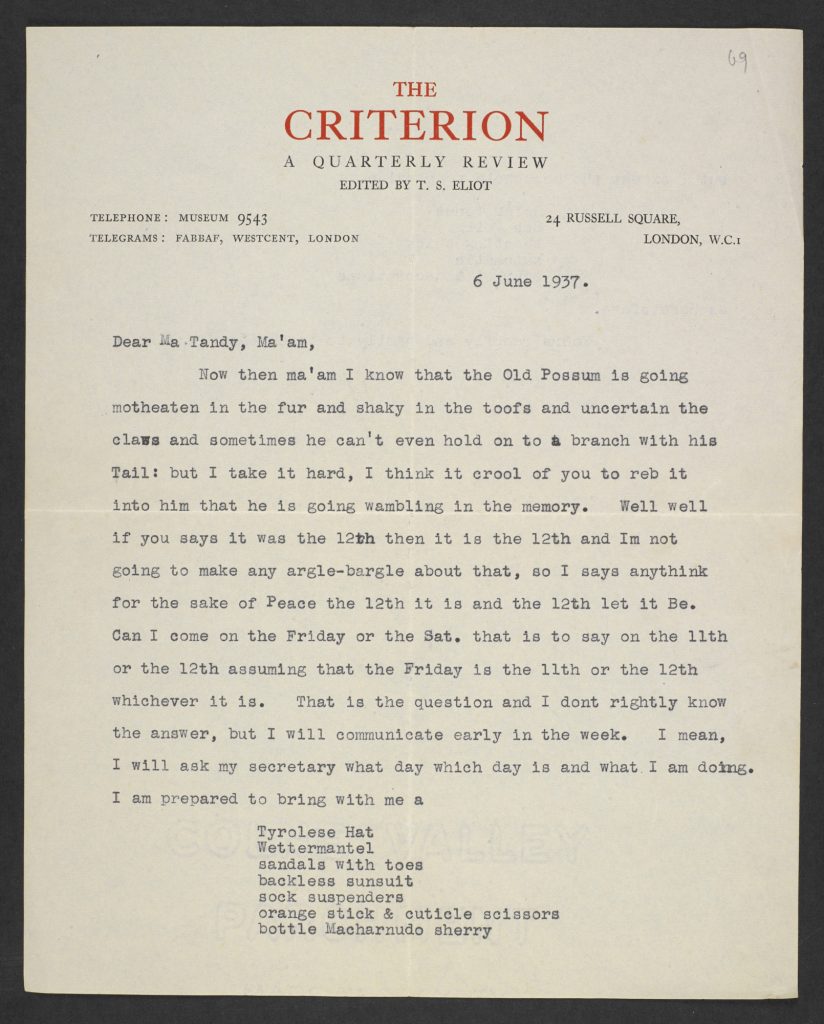

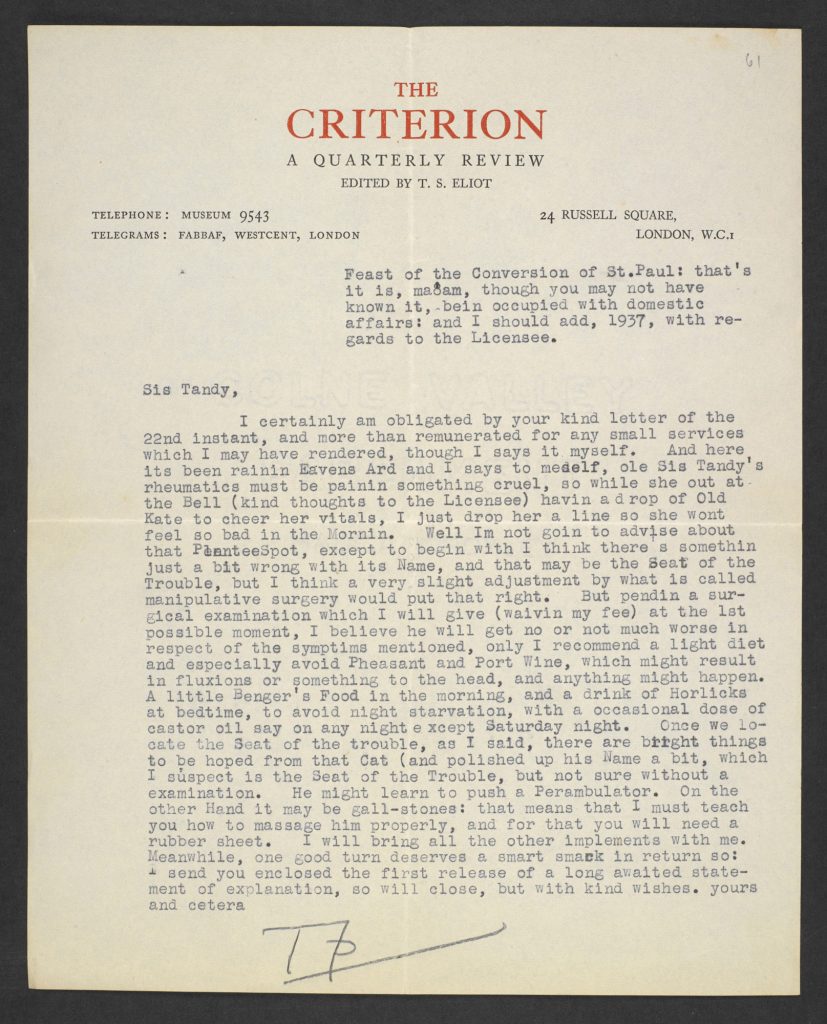

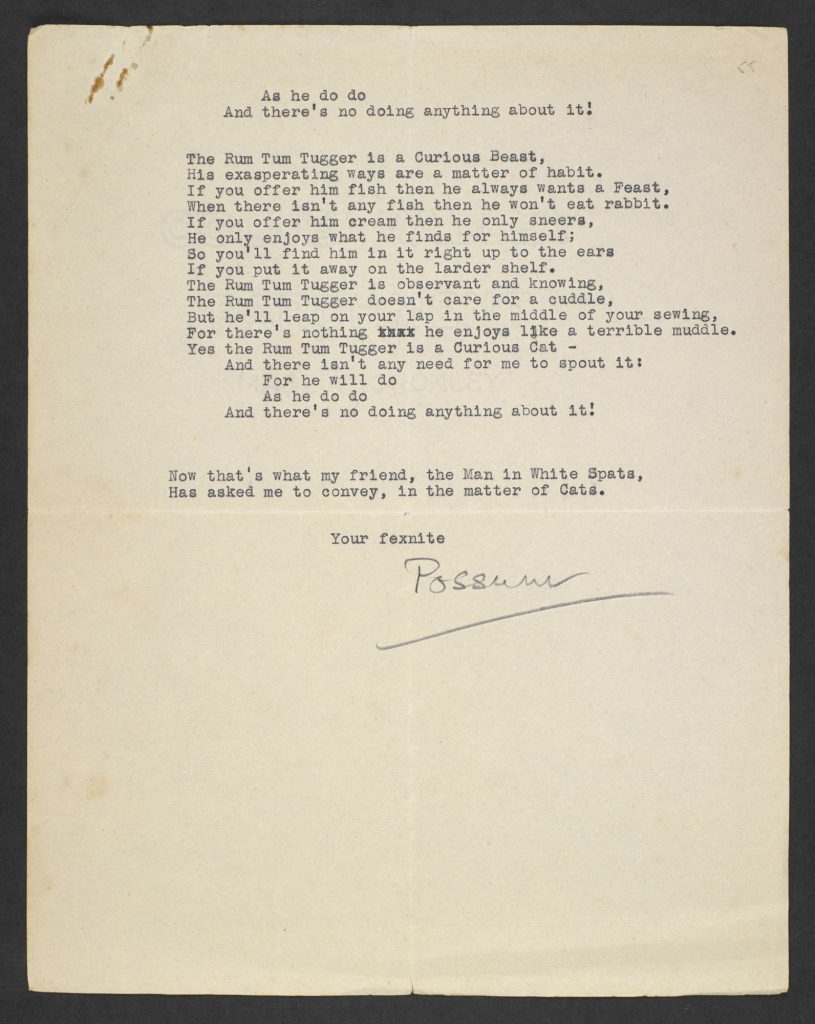

‘So far in my experience there are cheifly [sic] 4 kinds of Cat the Old Gumbie Cat the Practical Cat the Porpentine Cat and the Big Bravo Cat [sic]; I suspect that yours is a Bravo Cat by the looks of things’: T S Eliot shares his observations in a letter to Doris (Polly) Tandy, 4 November 1934.

Cats, as in Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Just So Stories’, walk by their ‘wild lone’ [1] – they are private. Eliot, among his friends, was called ‘Tom’. It echoes ‘tom cat’, the animal which goes out alone, wanting what it wants, at night. By itself.

There is, any ‘owner’ (so called) will agree, something strangely superior about the domestic cat – Felis domestica. They own themselves. The Devil has his obedient pack of hounds of hell: no sensible religion has ever elevated the dog to divine status. But for the ancient Egyptians the inner haughtiness of the cat had something god-like about it – a quality caught in one of the British Museum’s proudest possessions, the Gayer Anderson statuette:

The Gayer-Anderson cat is believed to date from the late period of ancient Egypt.

For Eliot, cats were intimate household companions but also objects of wonder and curiosity. And an appropriate subject for poetry.

Origins

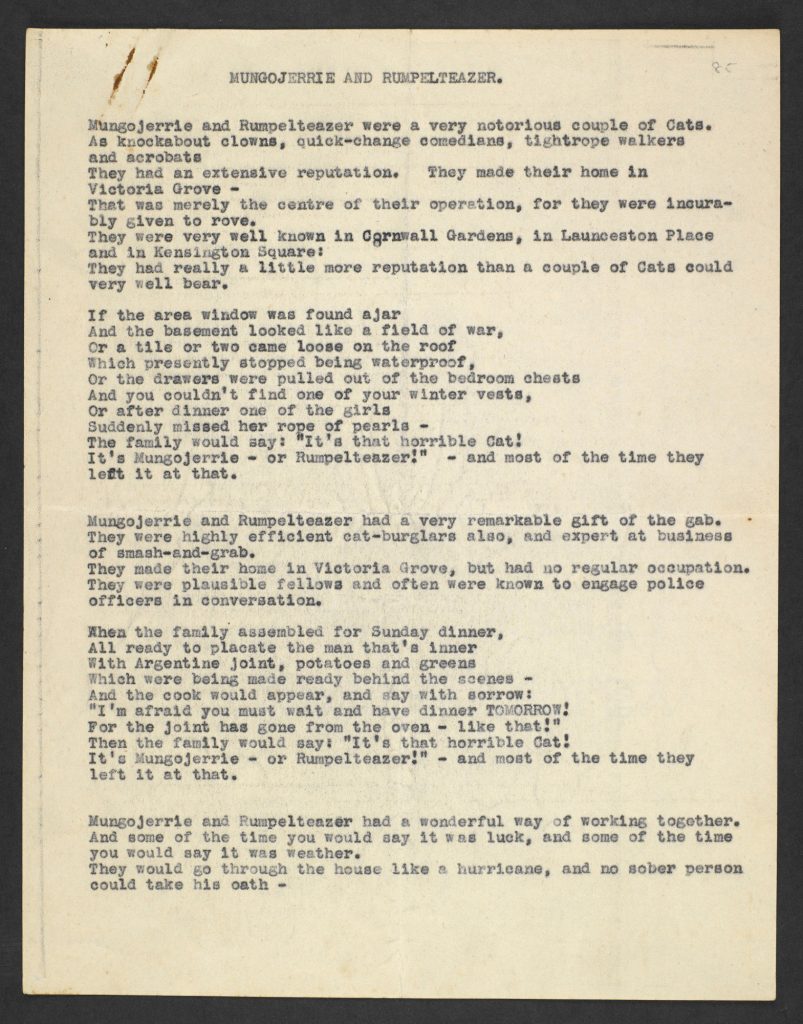

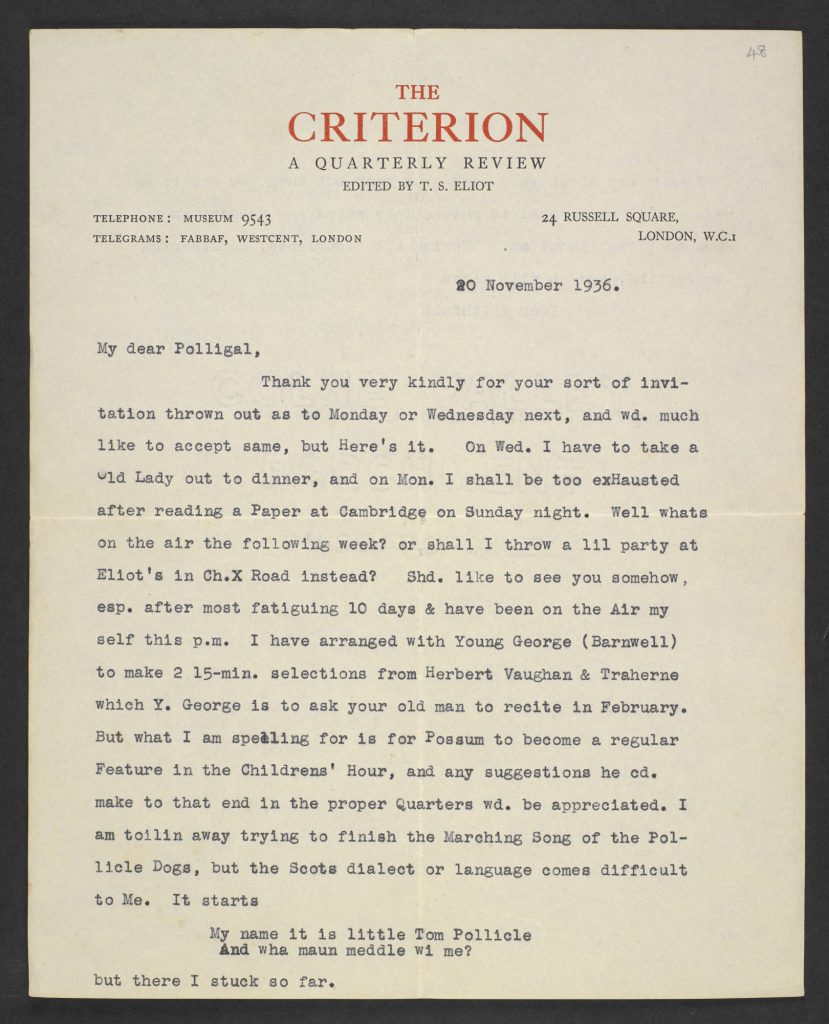

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats was begun in 1934–35. The separate poems were intended as gifts for the children of friends and the poet’s godchildren. A volume called ‘Mr Eliot’s Book of Pollicle Cats and Jellicle Cats’ was promised in 1936, but it never made print.

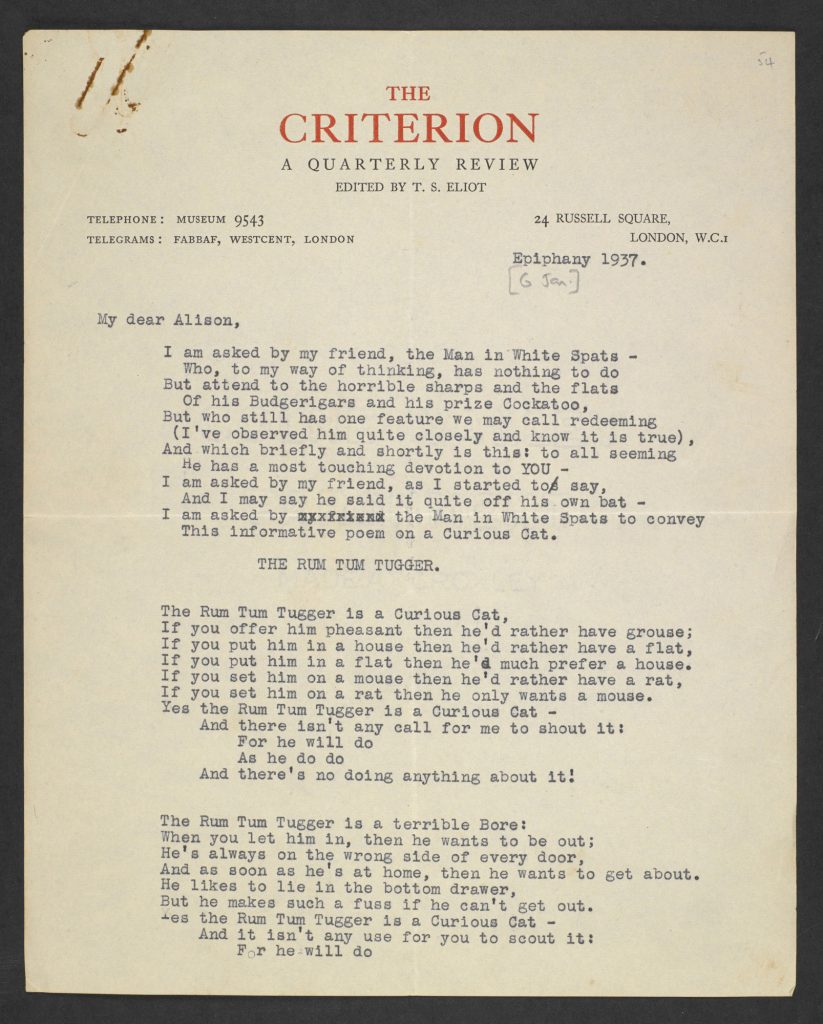

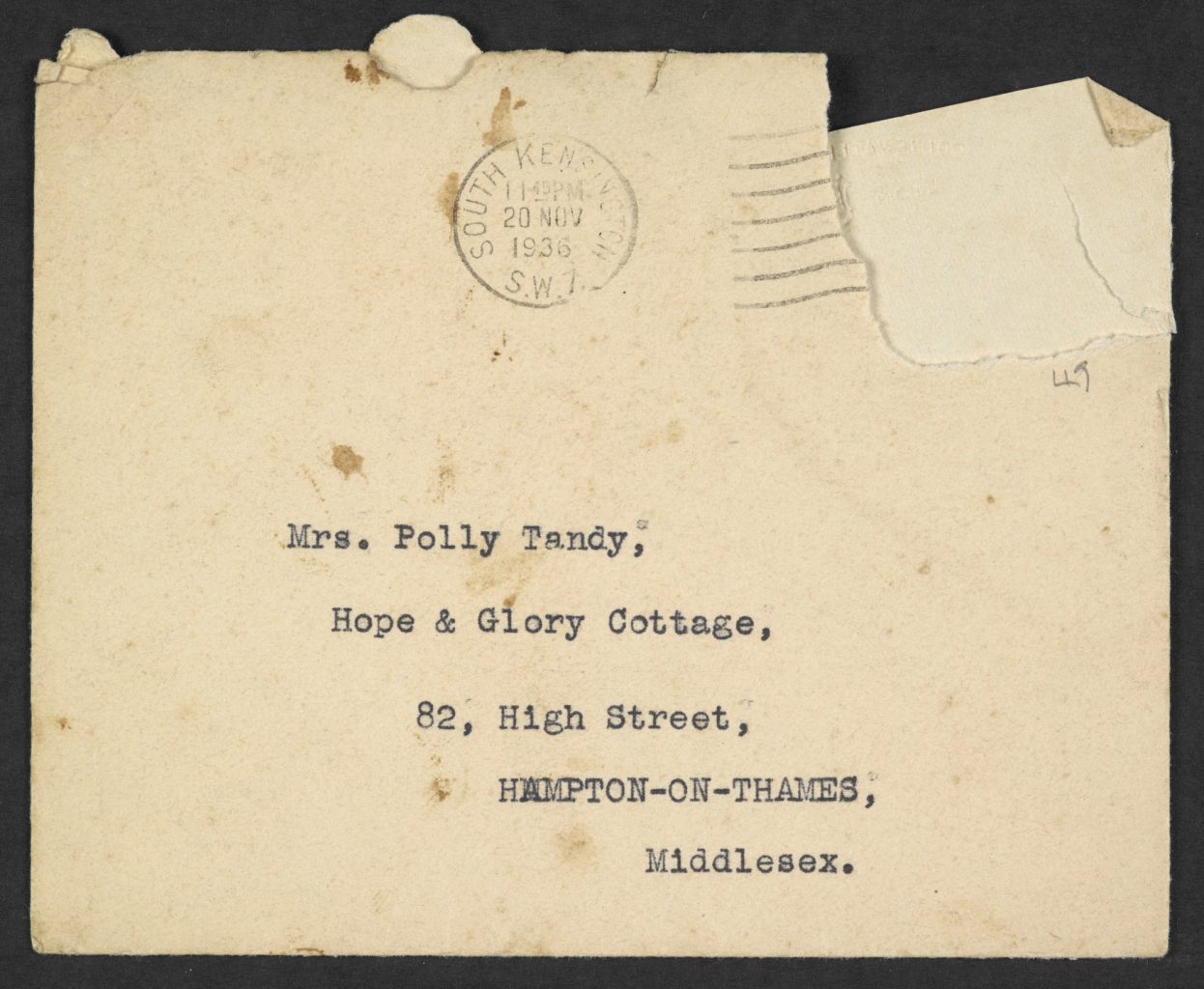

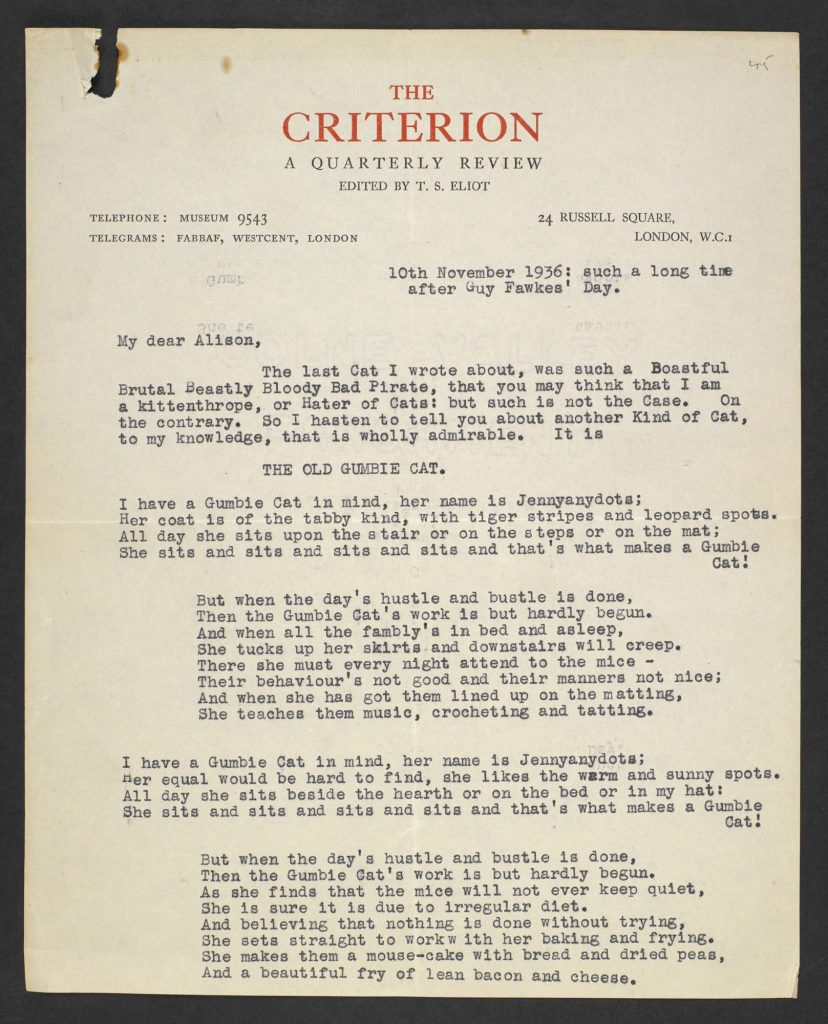

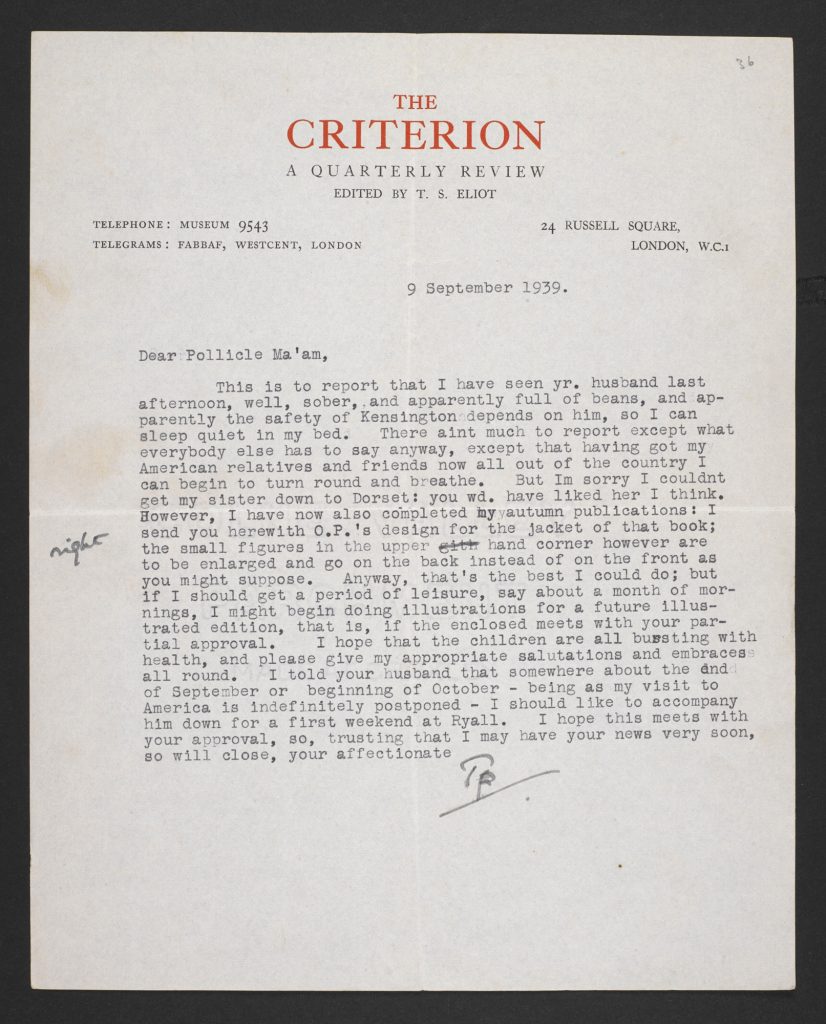

T S Eliot tested out the cat poems on the Tandy family (Geoffrey, Doris (Polly), and their three children Richard, Alison, and Anthea) in letters such as this one, sent on 10 November 1936, which contains a draft of ‘The Old Gumbie Cat’.

It’s clear that Eliot liked to recite the poems to his godchildren, such as those of his publisher-partner, Geoffrey Faber. Luckily, there survives a recording of him reading them.

The collection finally took book form in 1939. One poem, ‘Grizabella’ was dropped as being too ‘sad’ for young readers. A dozen named cats, of widely different character, made up the slim volume. Principal recipients of the poems over the years had been the children of Eliot’s business partner, Geoffrey Faber. The publishing house Faber published the poems.

Eliot’s poems drew, stylistically, on two well-established traditions. One was the nursery rhyme – the first poetry a child ever hears. For, example, the mournful:

Ding, dong, bell,

Pussy’s in the well.

Who put her in?

Little Johnny Flynn.

Who pulled her out?

Little Tommy Stout.

Shakespeare refers to this poem in his plays. His mother must have recited it at bedtime to little William.

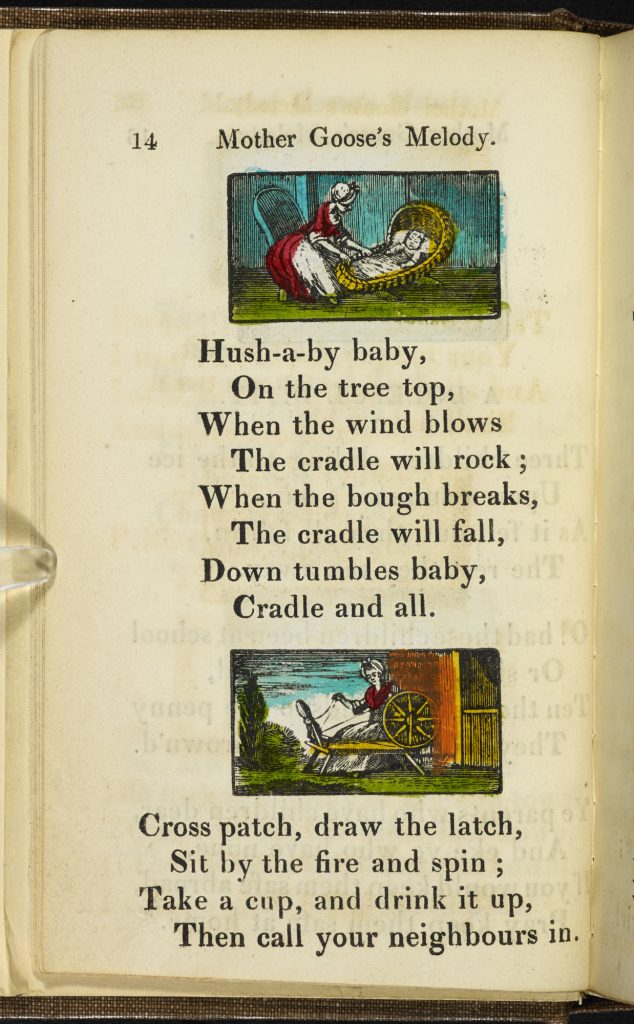

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes including ‘High diddle diddle’, also known as ‘Hey diddle diddle’ or ‘The cat and the fiddle’, 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

An early book of illustrated children’s nursery rhymes from 1817.

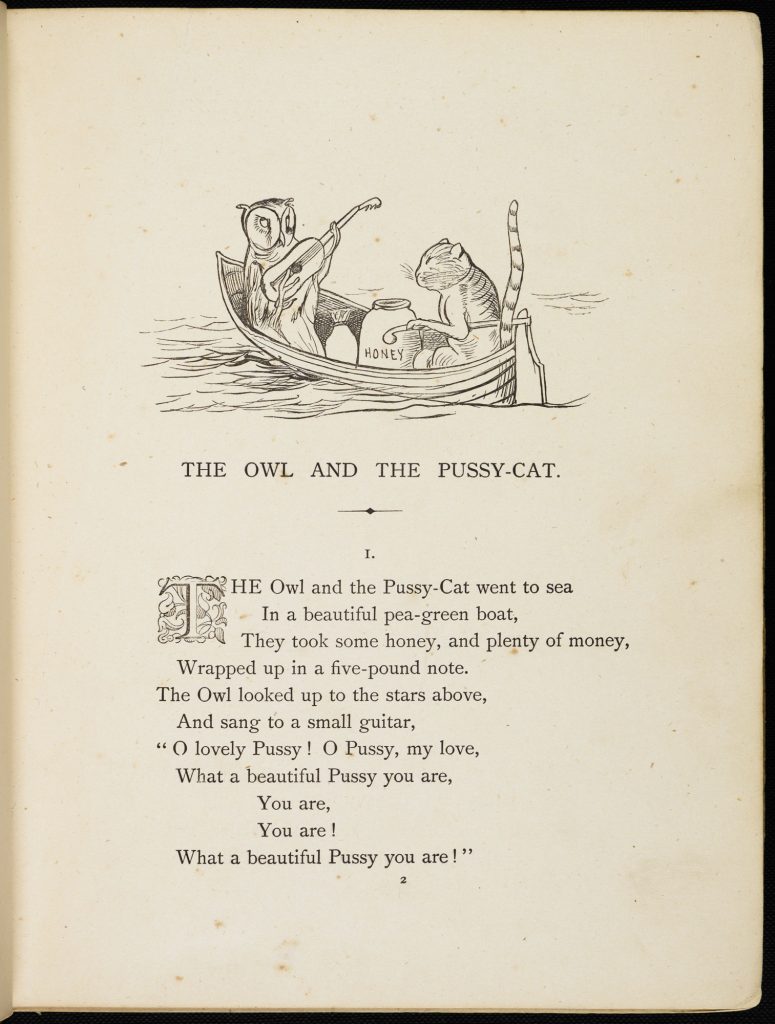

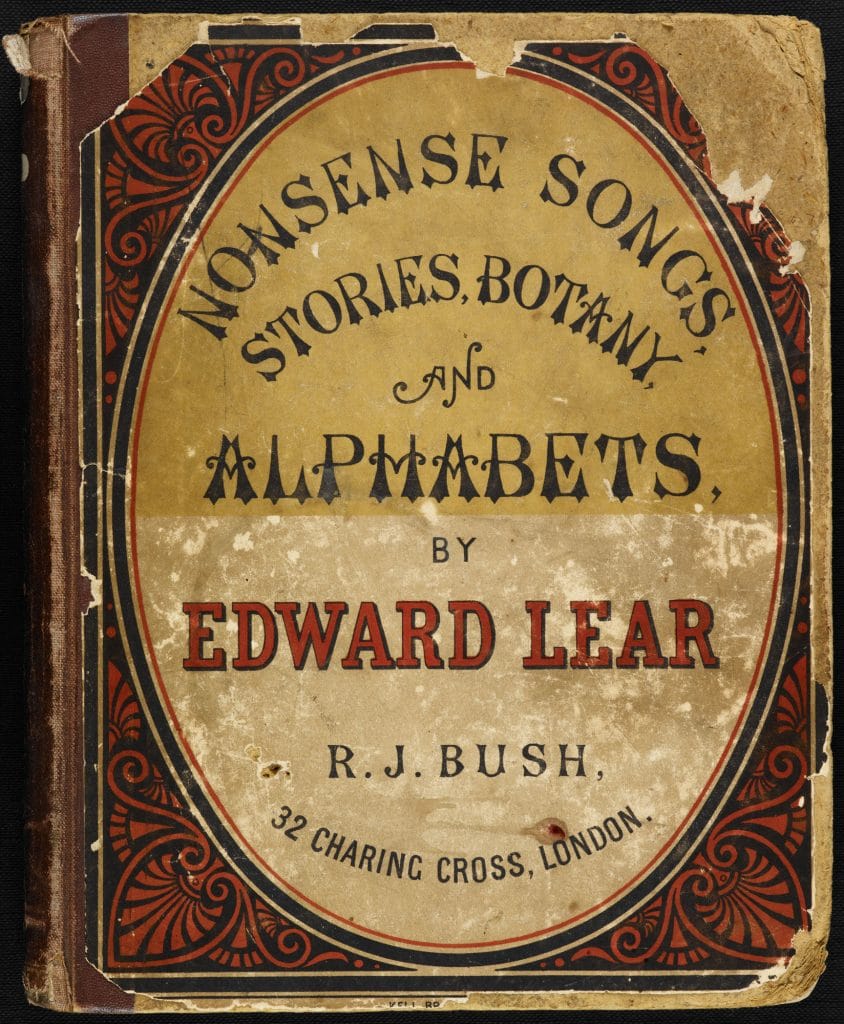

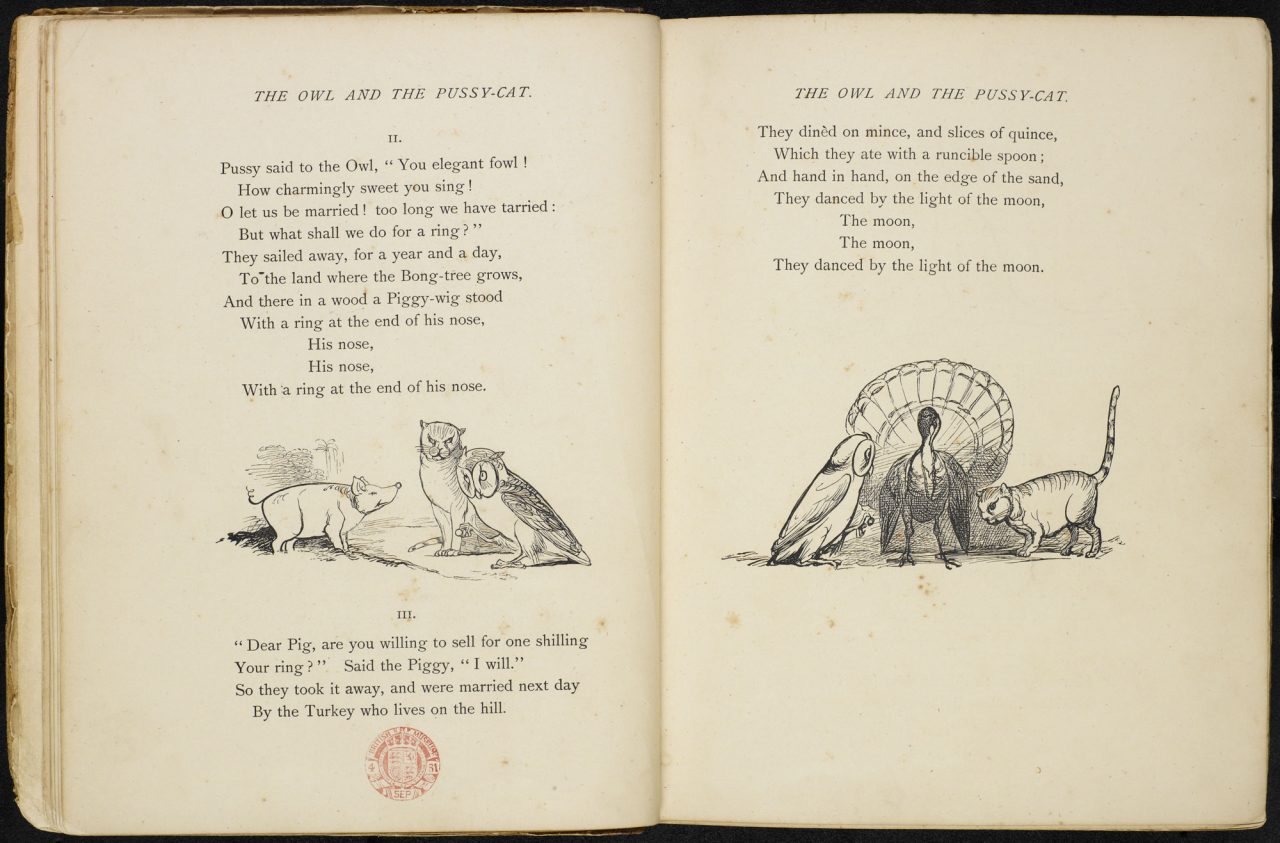

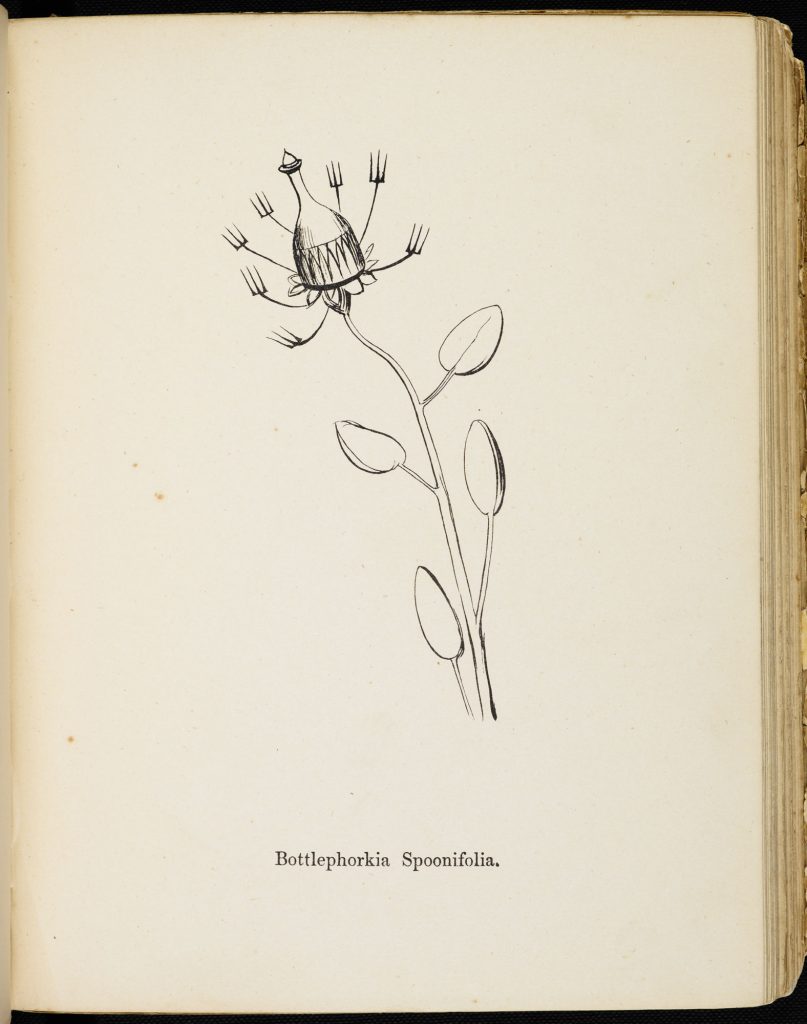

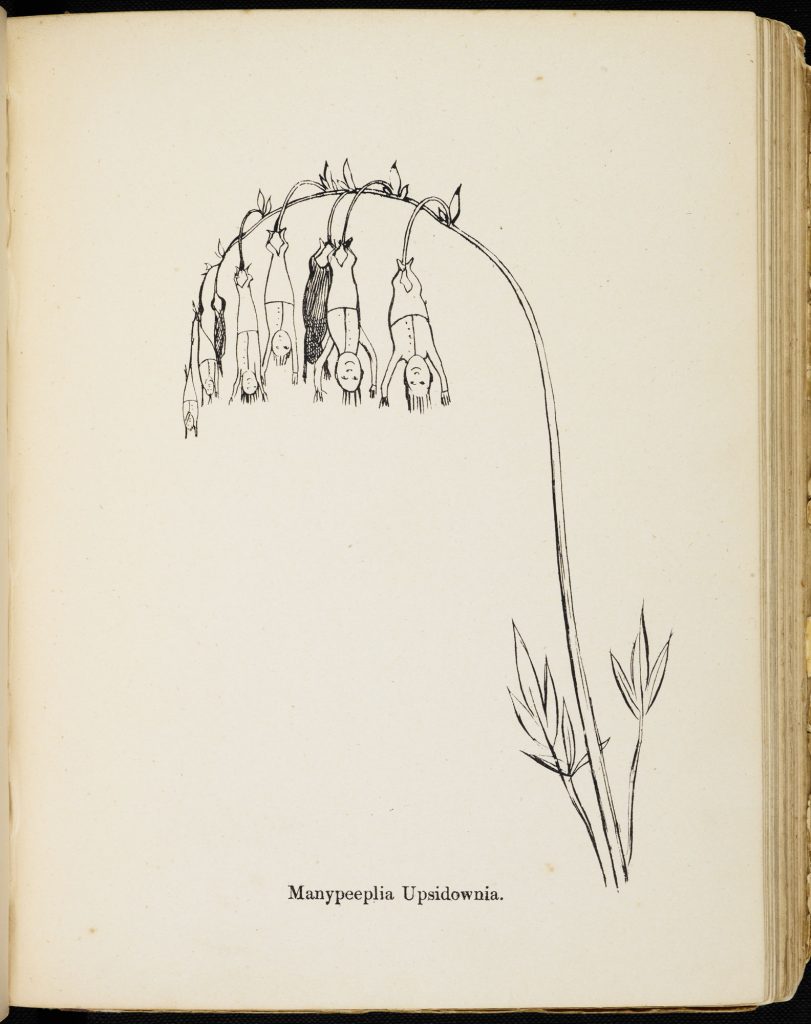

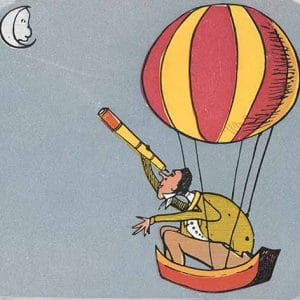

The other tradition – more interesting to the adult – is the nonsense poetry of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, most derivatively ‘The Owl and the Pussy Cat’:

The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat,

They took some honey, and plenty of money,

Wrapped up in a five-pound note.

Eliot adopted the heavy rhythm and rhyme of traditional children’s verse.

Edward’s Lear famous nonsense poem, ‘The Owl and the Pussy-Cat’, first published in 1870.

Edward’s Lear famous nonsense poem, ‘The Owl and the Pussy-Cat’, first published in 1870.

Edward’s Lear famous nonsense poem, ‘The Owl and the Pussy-Cat’, first published in 1870.

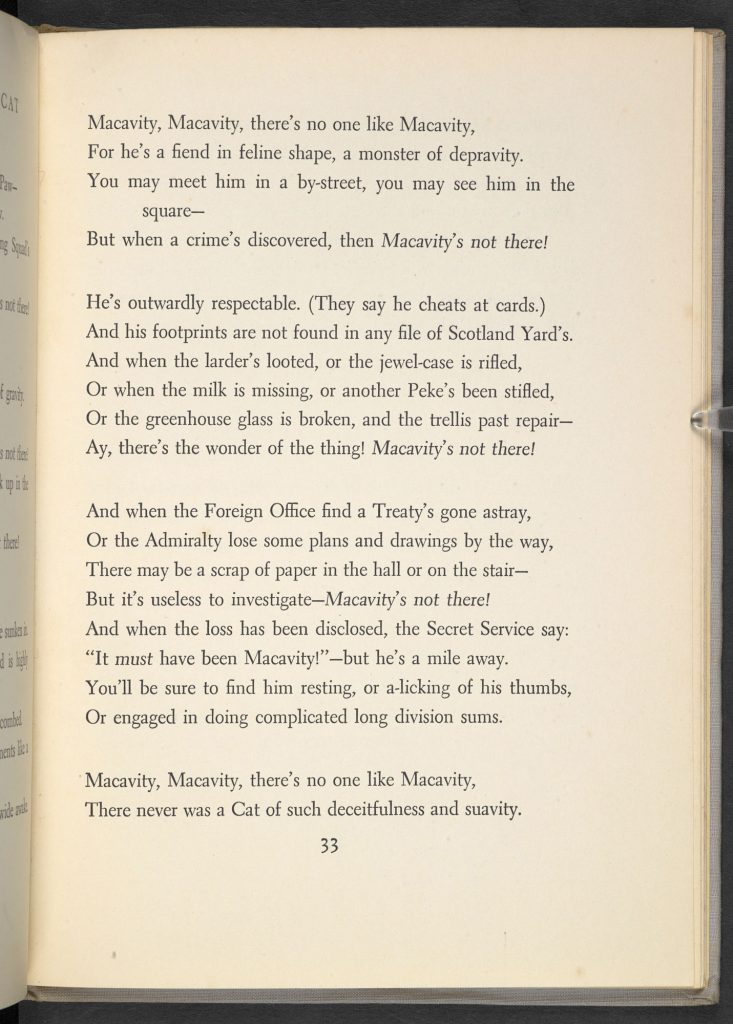

Eliot also drew on various private passions. He was a great lover of the Sherlock Holmes stories. The poem which is everyone’s favourite, ‘Macavity the Mystery Cat’, clearly draws on Conan Doyle’s ‘Napoleon of Crime’, Professor Moriarty:

Macavity’s a Mystery Cat: he’s called the Hidden Paw

For he’s the master criminal who can defy the Law.

He’s the bafflement of Scotland Yard, the Flying Squad’s despair:

For when they reach the scene of crime – Macavity’s not there!

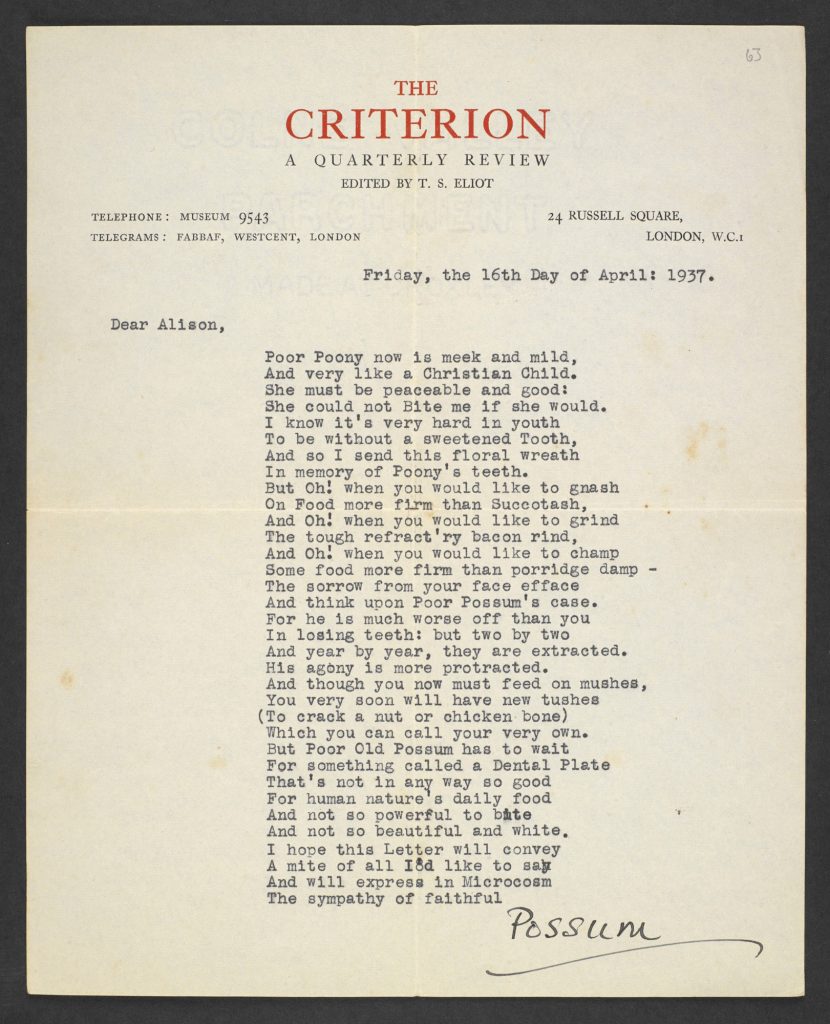

Eliot, who had none of his own, had the softest of spots for children. As Peter Ackroyd wryly says in his biography of Eliot, he loved small animals, whether of the four- or two-legged variety.

The dust-jacket and title page

Eliot, as publisher, designed the dust-jacket and did the cover illustration himself.

Front cover to Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats illustrated by T S Eliot, 1939.

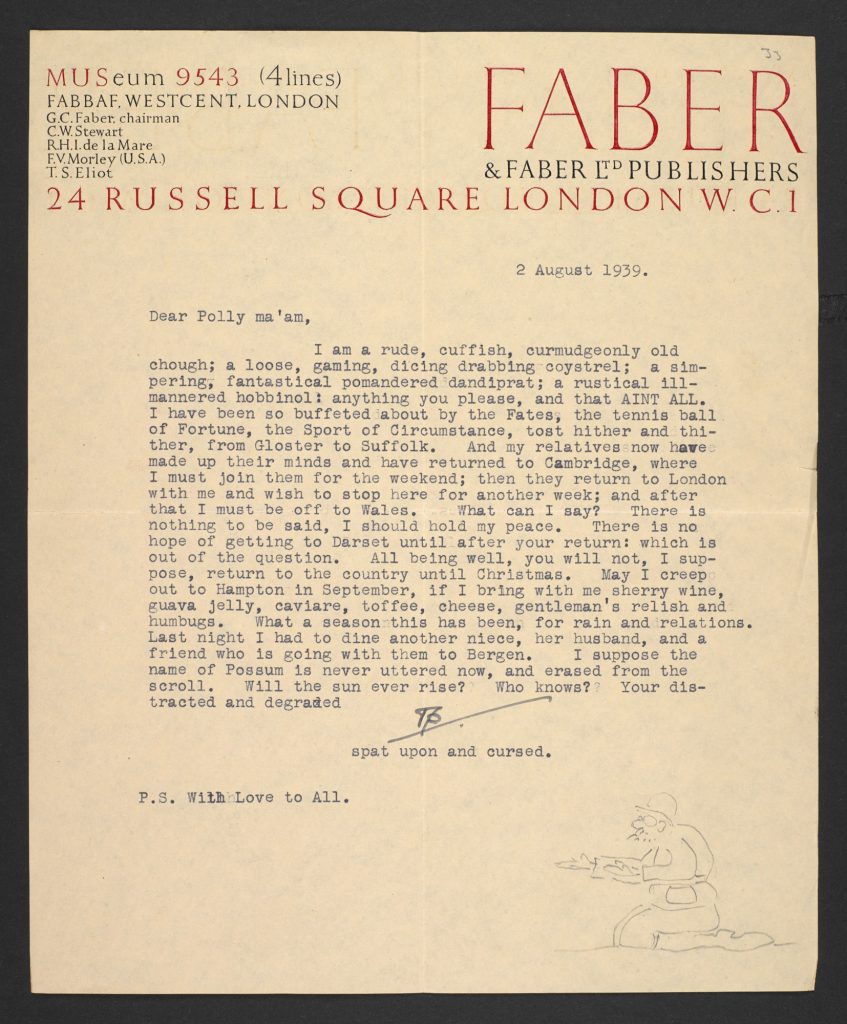

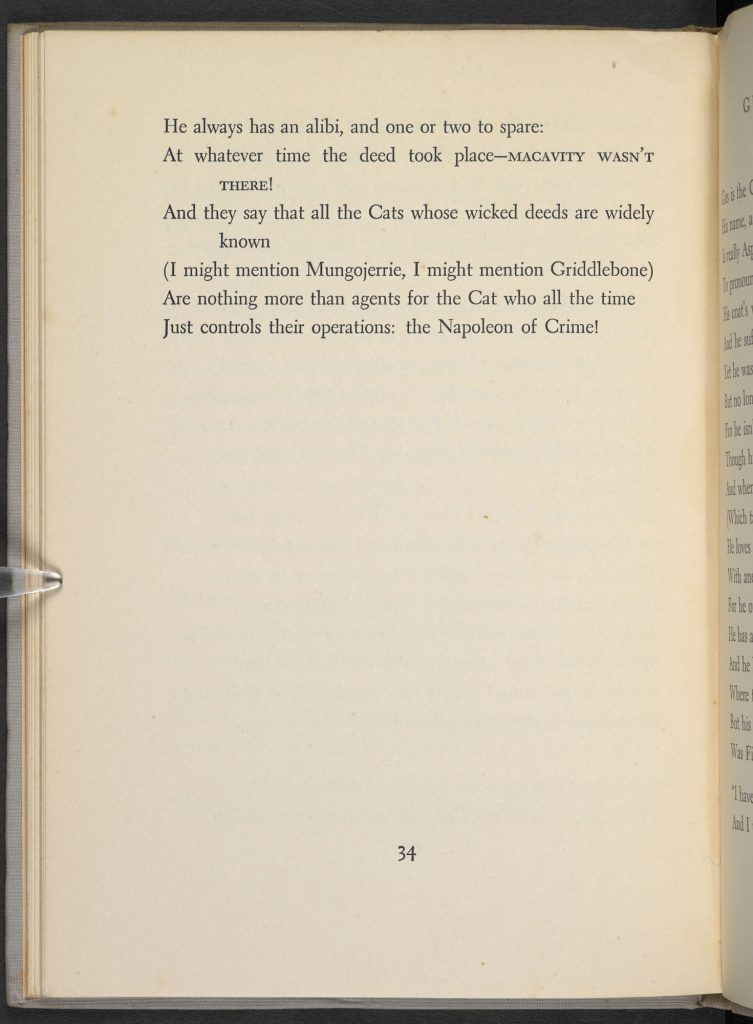

Self-portrait caricature by T S Eliot, sketched in pencil at the bottom of a letter to Doris (Polly) Tandy, 2 August 1939.

Eliot guys himself as the stuffily overdressed figure helping his nine feline friends up the ladder – to escape from what? 1939, one recalls, was the year in which World War Two was declared. It was what W H Auden called ‘an age of anxiety’.

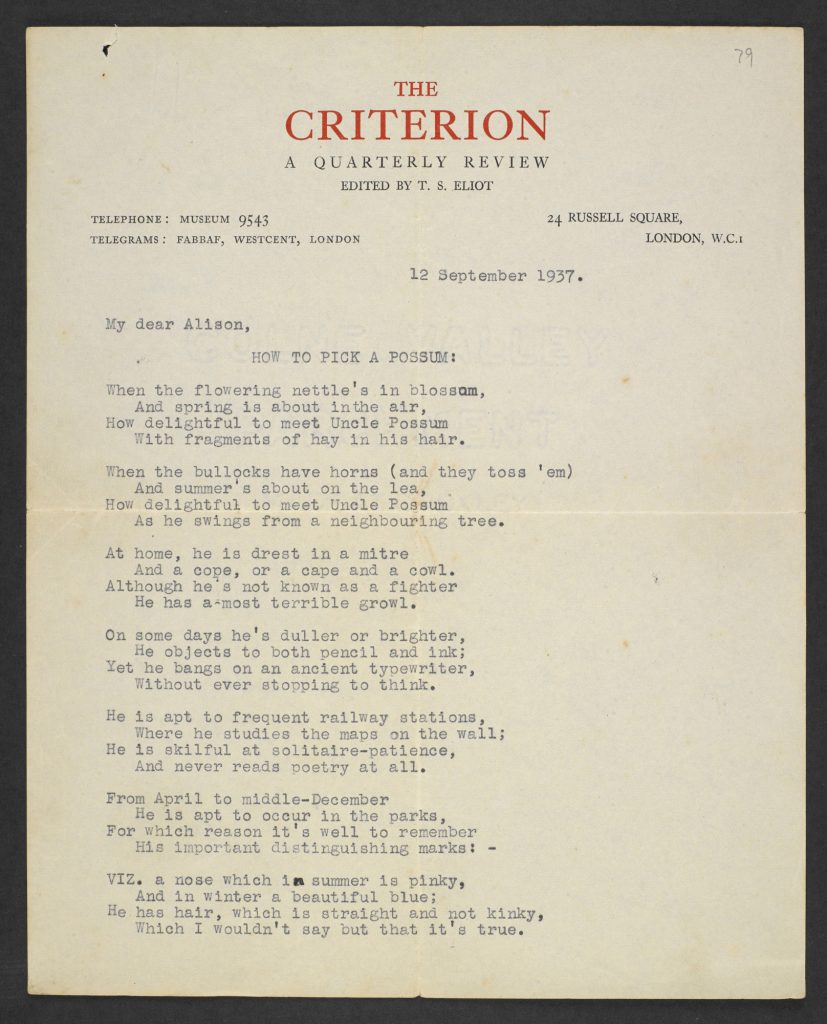

There is a discreetly authorial ‘T.S. Eliot’ at the top, but the central banner statement is: ‘Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats’. Eliot was nicknamed ‘Old Possum’ by his close comrade in modernist poetry, Ezra Pound (il miglior fabbro, ‘the better craftsman’, as he is hailed in the dedication to The Waste Land). In private correspondence, Eliot jokily called Pound ‘Brer Rabbit’. It was an allusion to Joel Chandler Harris’s ‘Uncle Remus’ stories. It pleased these two eminent men of letters, when having fun between themselves, to lapse into mock ‘tar baby’ African-American dialect.

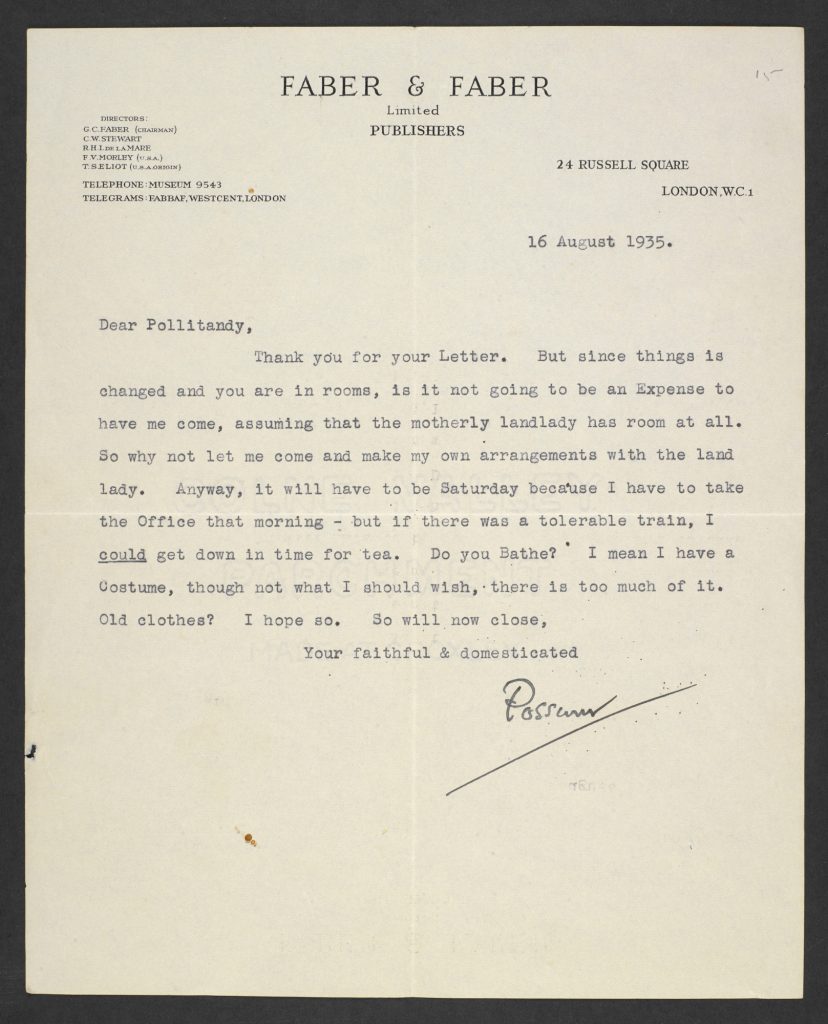

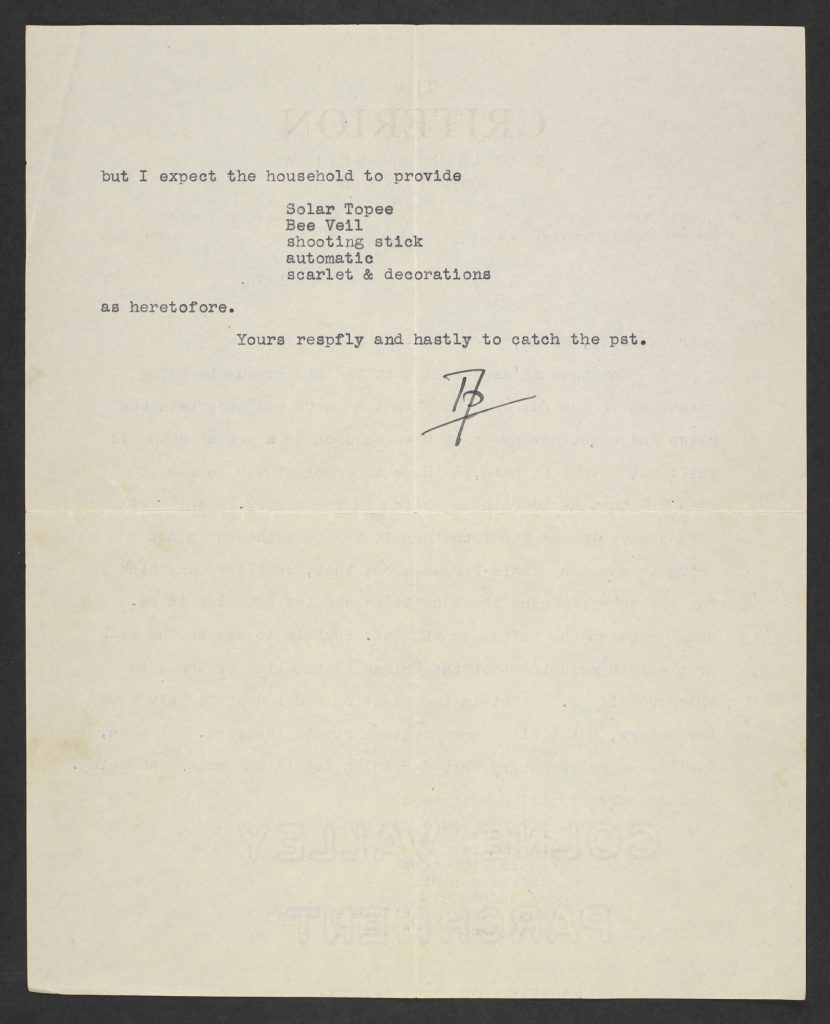

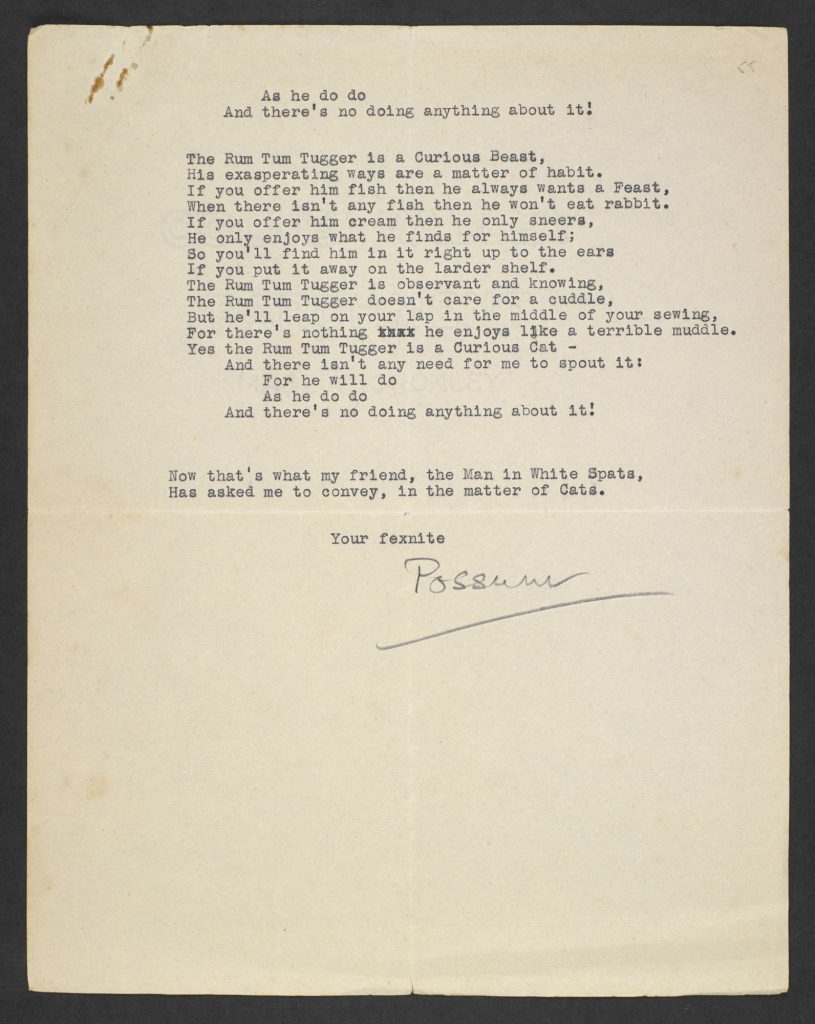

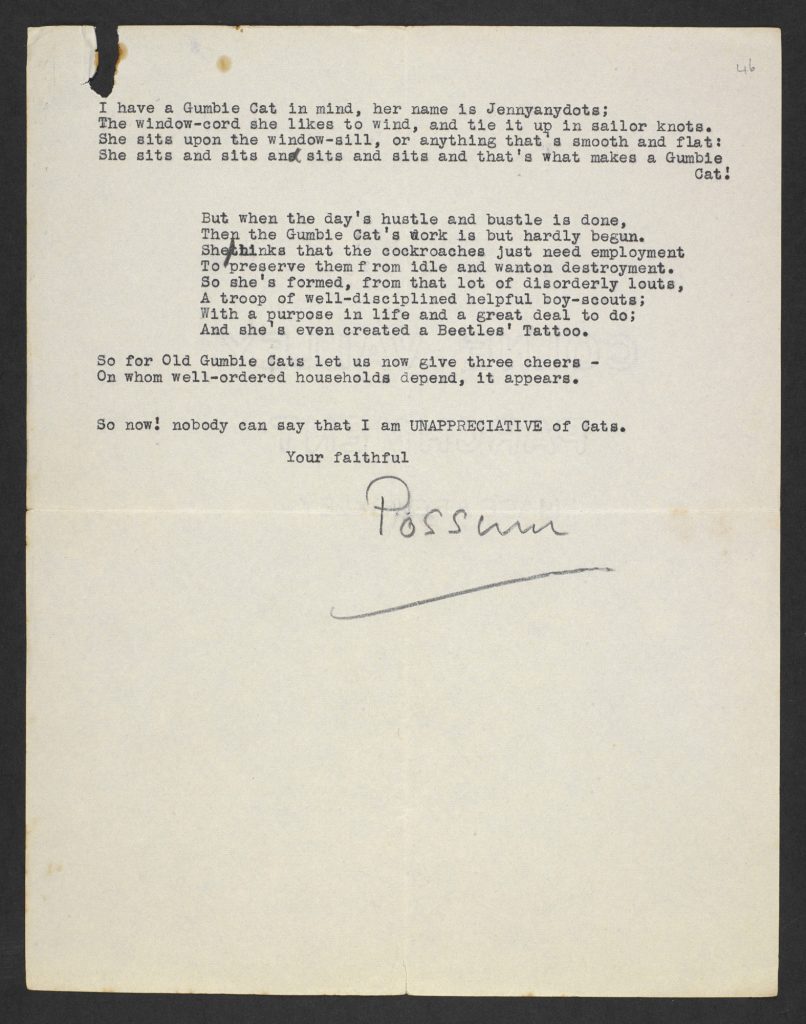

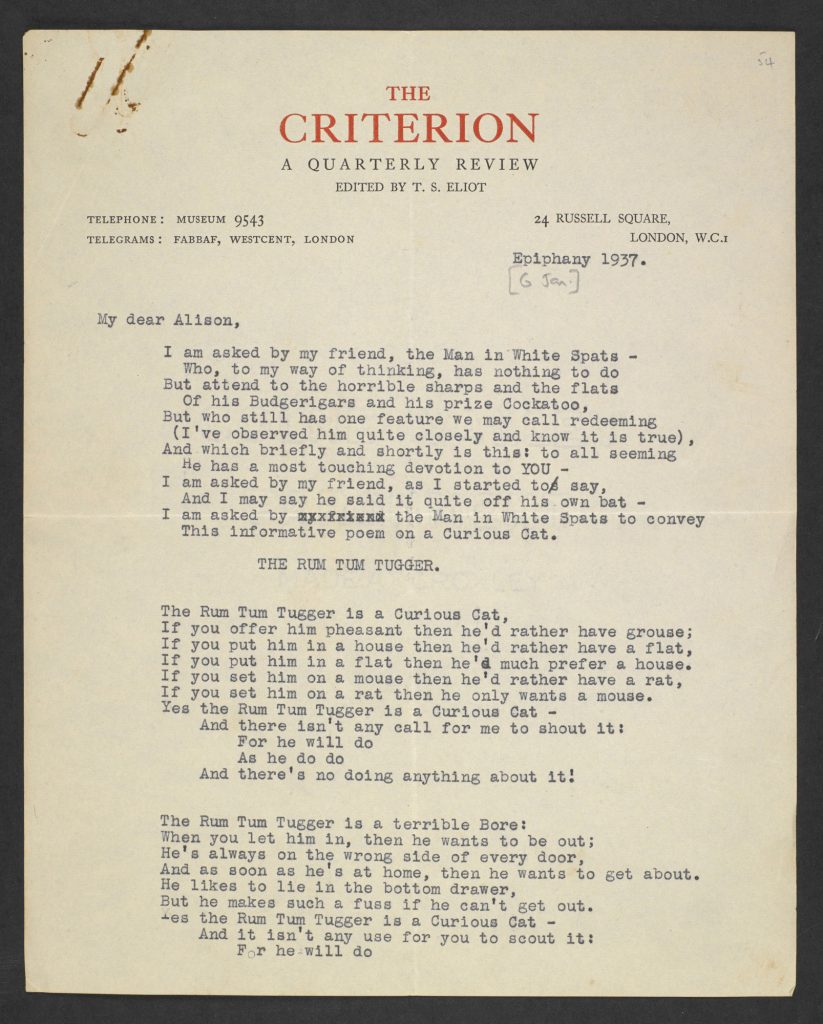

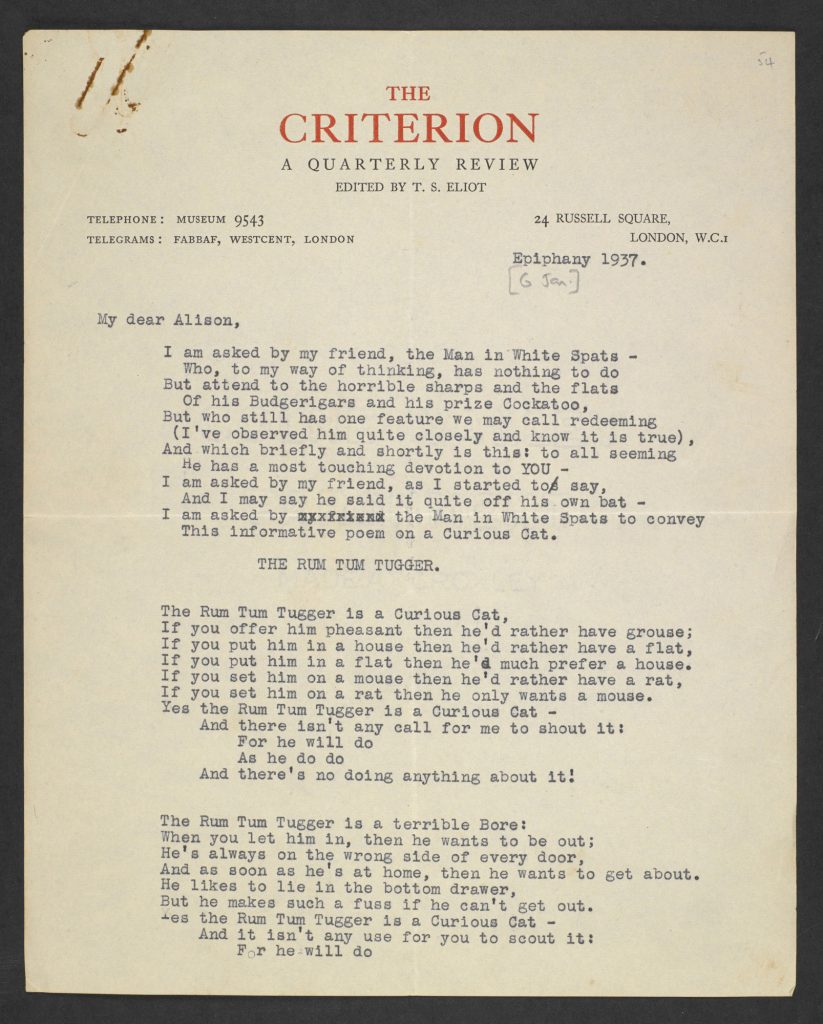

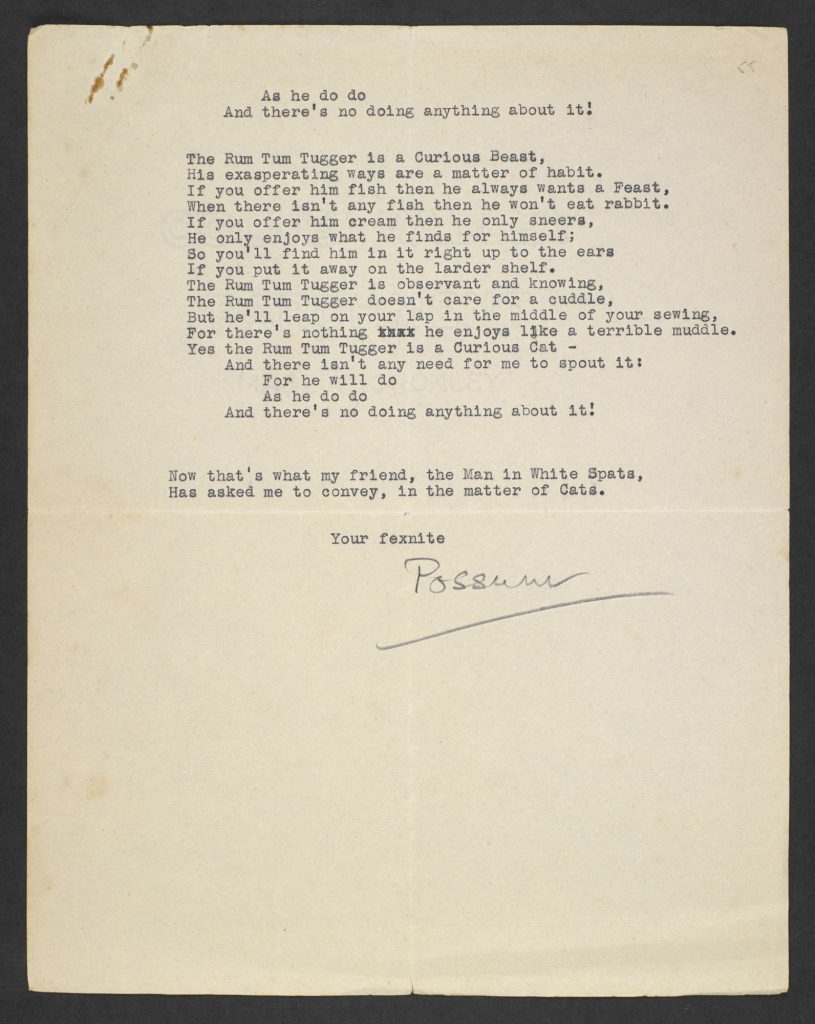

T S Eliot signed many of his letters to the Tandy family as ‘Possum’, ‘Old Possum’, or ‘T.P.’ (Tom Possum).

The possum, in the Uncle Remus tales, and in folklore, ‘plays dead’ when in danger. Pound’s nickname for his friend mocks Eliot lifelong practice of giving away as little of himself as possible: in life, and in poetry.

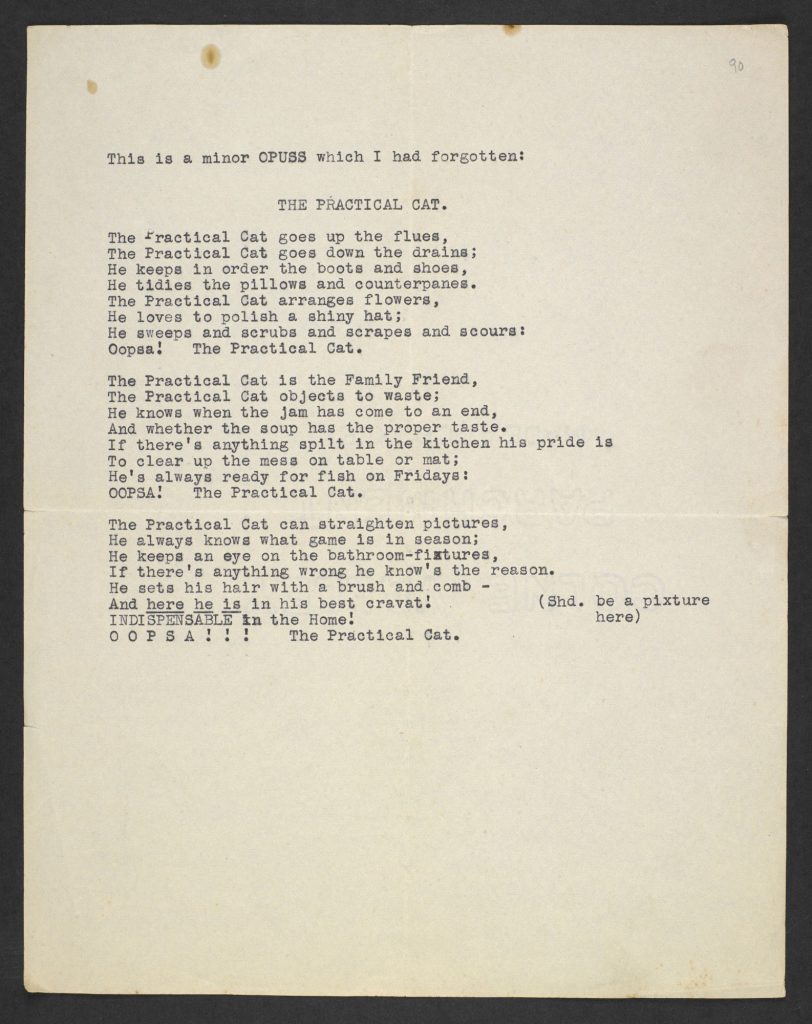

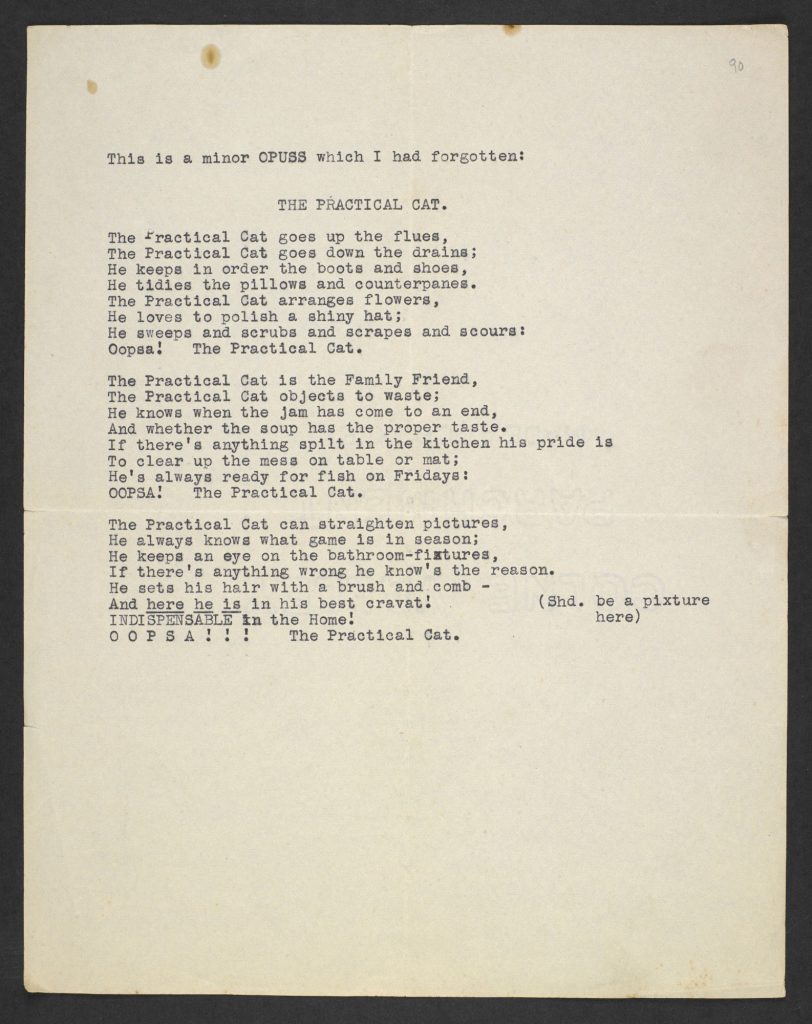

And why ‘practical’? Because Old Possum’s cats all ‘do’ something. They are not there merely to be stroked, purr and adorn the household.

‘The Practical Cat goes up the flues, / The Practical Cat goes down the drains’: a draft of a poem sent from T S Eliot to the Tandy family, undated.

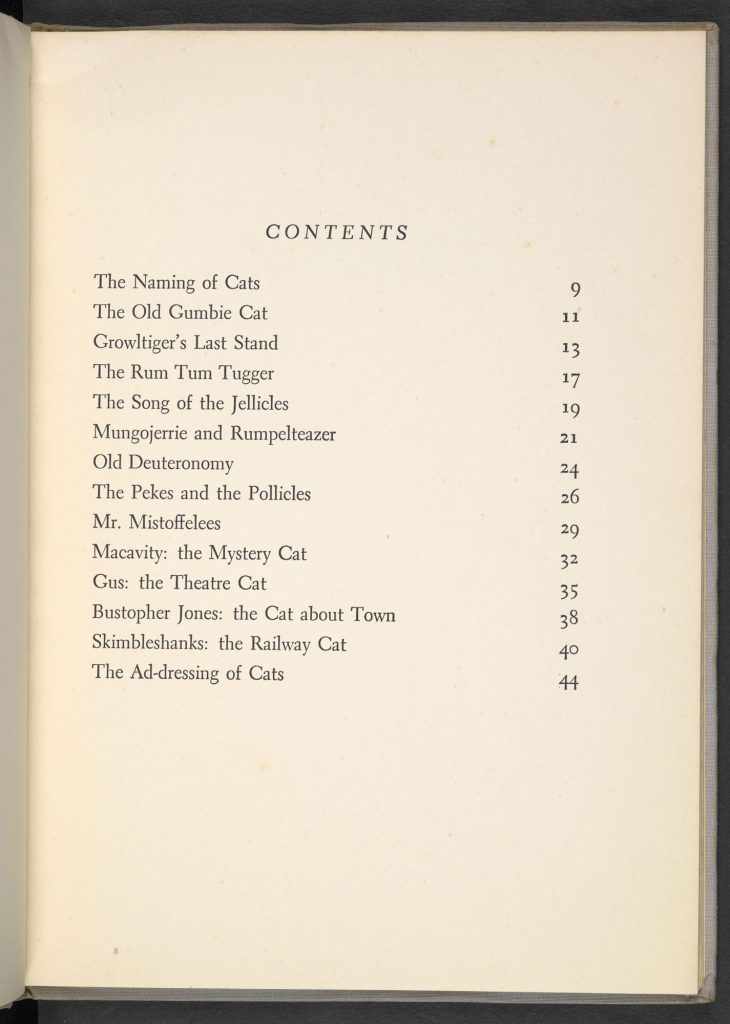

Contents

The collection opens with a general observation. Every cat, says ‘Old Possum’, has three names – its group name (e.g. ‘tabby’, ‘marmalade’, ‘ginger’) a house name (‘Mog’, ‘Oscar’ or whatever) and a personal name which may never be divulged. Cats, unlike dogs, do not answer to their name when called. Every owner knows that – sometimes to their frustration.

There follows a gallery of feline portraits. The Old Gumbie Cat (‘Jennyanydots’) is a busybody, always ‘a-doin sumpn’ in and around the house, after the day’s ‘hustle and bustle’ is done. A ‘mammy in the kitchen’ figure.

Growltiger, by contrast, is a ‘bucko’. He lives on a coastal barge and lives to fight – particularly foreigners like the invading hordes of Siamese cats. Toffs, all of them. The poem describes his ‘last stand’. He is vanquished and:

Oh there was joy in Wapping when the news flew through the land;

At Maidenhead and Henley there was dancing on the strand.

Rats were roasted whole at Brentford, and at Victoria Dock,

And a day of celebration was commanded in Bangkok.

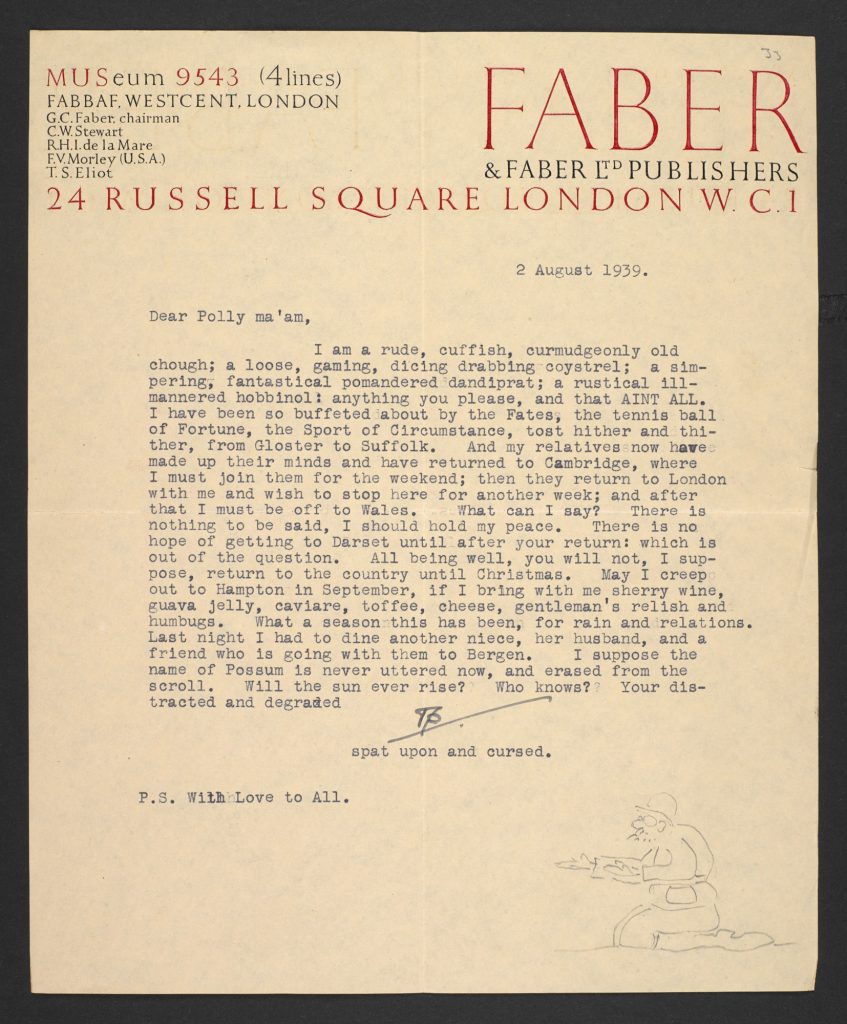

T S Eliot sends a draft of ‘The Rum Tum Tigger’ to Alison Tandy, 6 January 1937.

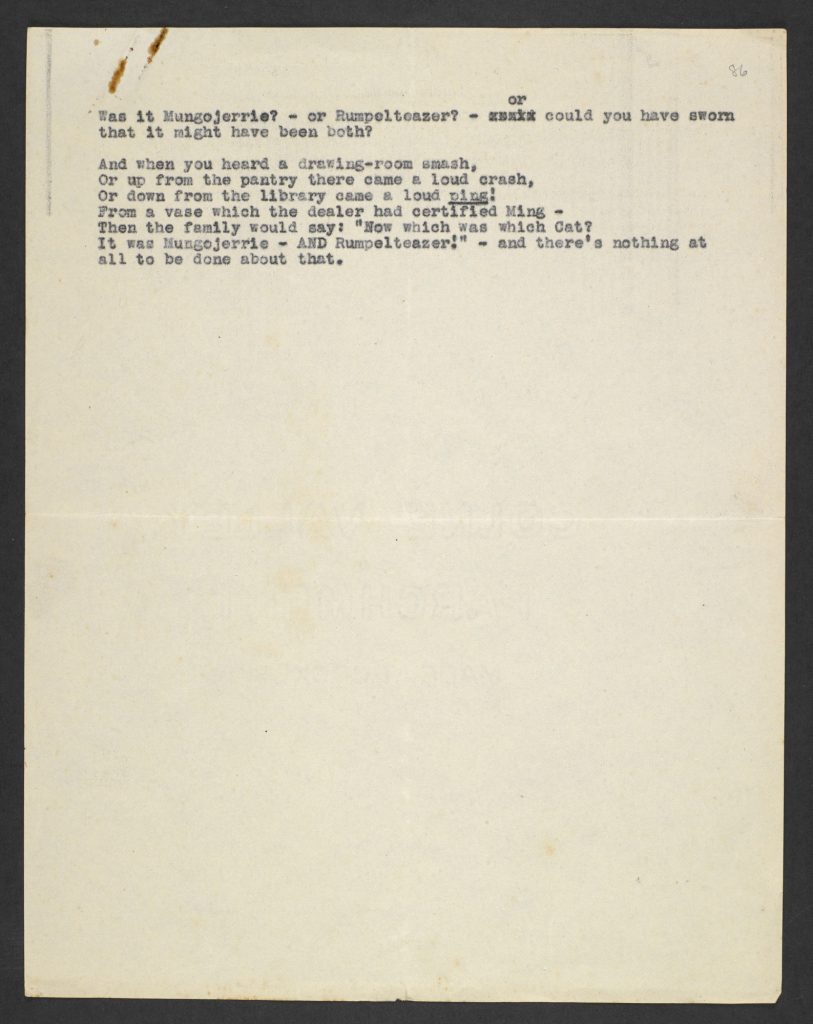

The Rum Tum Tugger is a ‘curious cat’ who can never make up his mind and is ‘a terrible bore’. The ‘Jellicles’ are a merry band who come out at night, dance and ‘caterwaul’. Mungojerrie and Rumpelteazer are music-hall performers (Eliot loved the English music hall):

As knockabout clown, quick-change comedians,

tight-rope walkers and acrobats

They had extensive reputation.

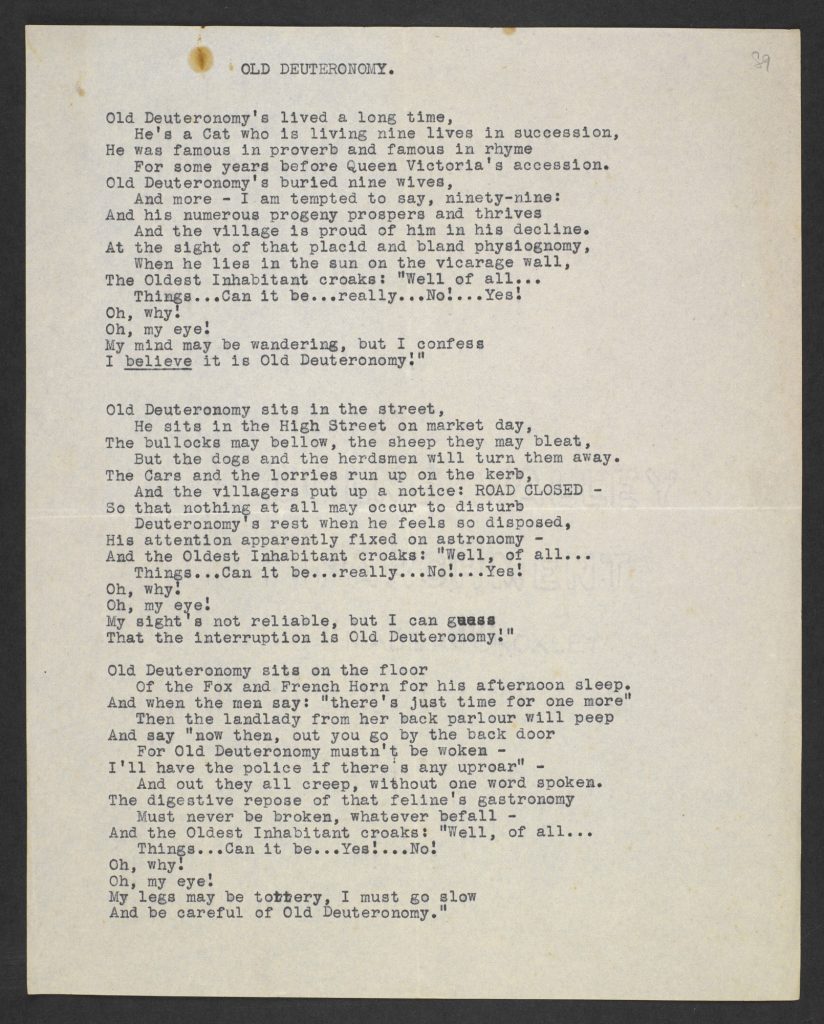

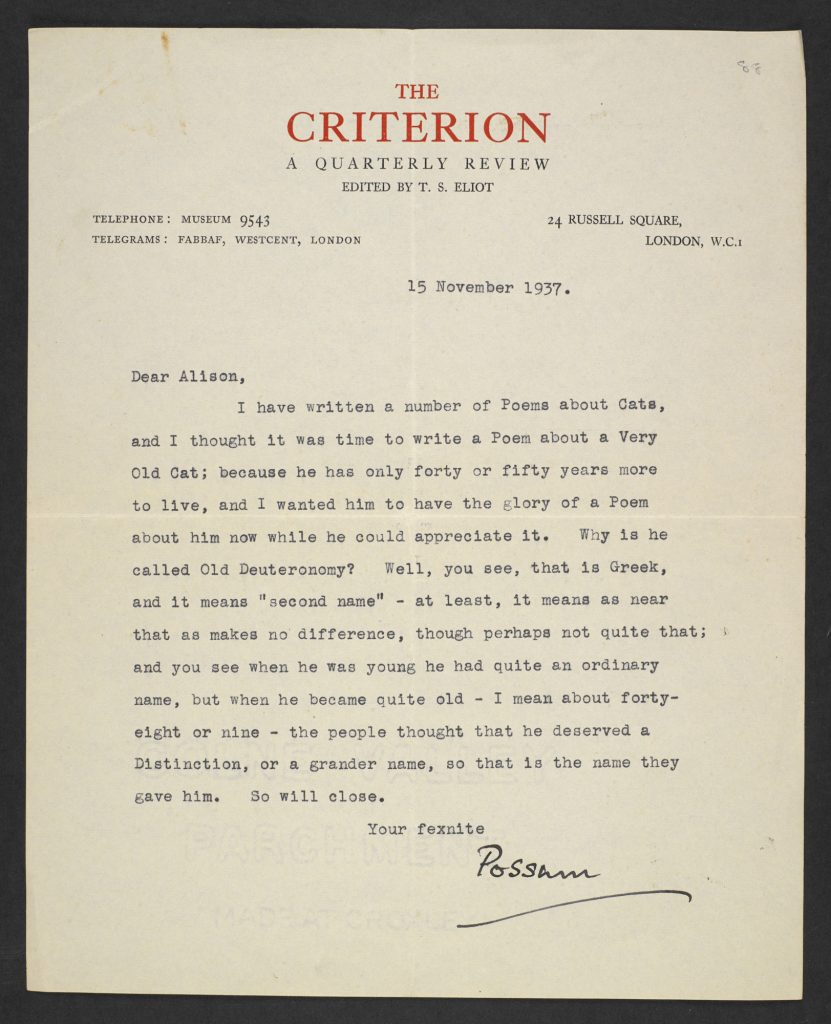

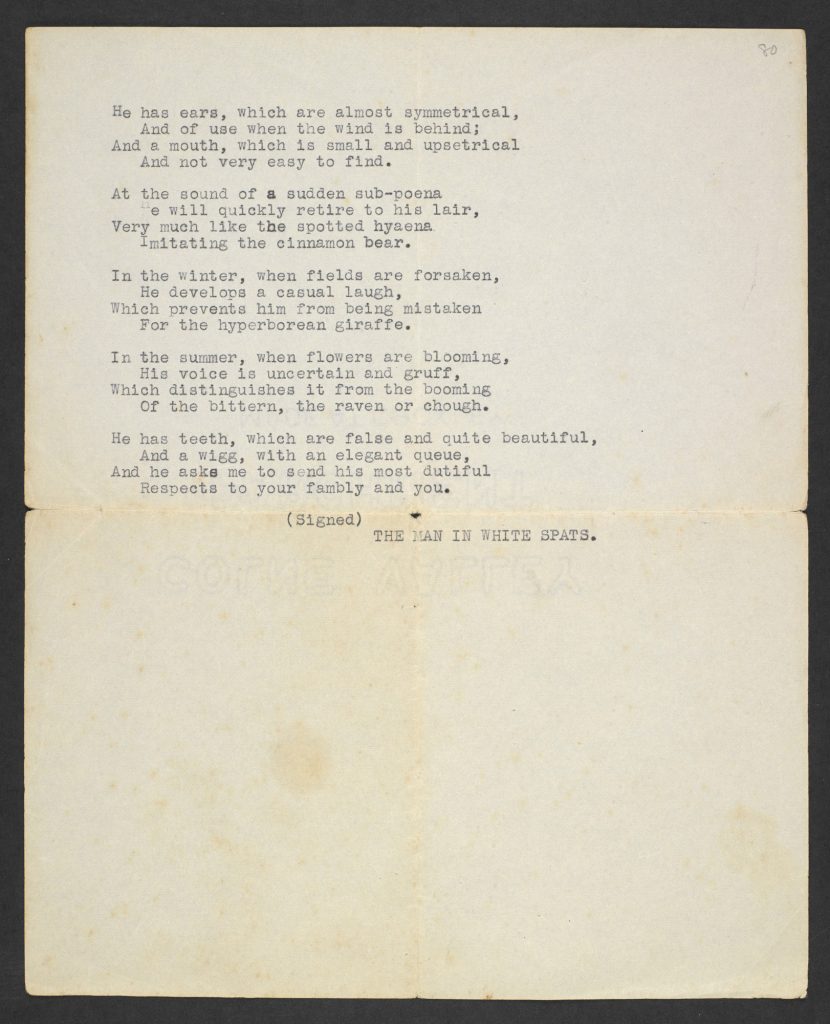

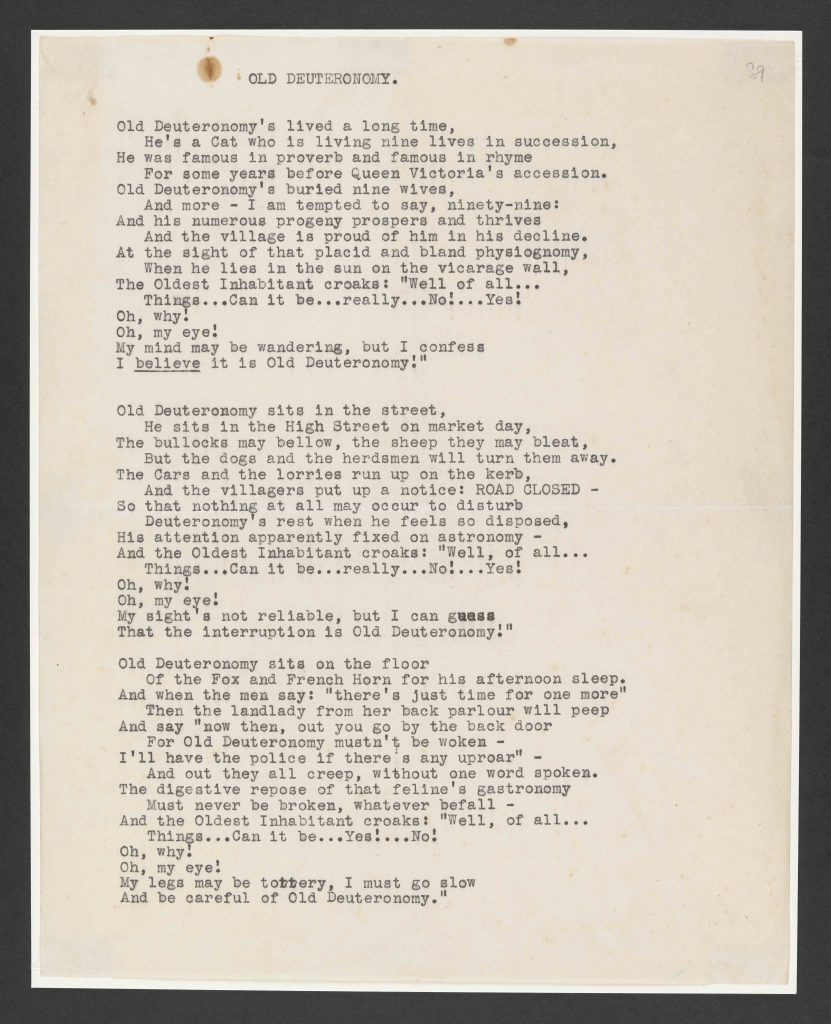

Old Deuteronomy, as his name suggests, is a mournful old mog. All cats have nine lives, but the Methuselean Deutoronomy ‘has buried nine wives’. He will outlive us all.

The following poem celebrates ‘The Awefull [sic] Battle of the Pekes and the Pollicles (Together with Some Account of the Participation of the Pugs and the Poms and the Intervention of the Great Rumpus Cat)’. The word ‘pollicle’ is a version of ‘poor little dog’. ‘Pekes’ are Pekinese dogs, and ‘Poms’ pomerians. The battle rages, the police dogs are ineffective until: ‘Why who should stalk out but the GREAT RUMPUSCAT. / His eyes were like fireballs, fearfully blazing.’

Peace is duly restored. Mr Mistoffelees (i.e. Satan’s minister, Mephistopheles) is a conjurer and, like his namesake, an inveterate trickster. Macavity is the Mystery Cat, Gus the Theatre Cat and Bustopher Jones the Cat about Town. Without Skimbleshanks, the Railway Cat, the night mail train cannot run. His ‘nimbleness’ (like that of the fingers of the mail sorters) is essential to next morning’s letters.

And so ends the collection with the sage reminder ‘A CAT IS NOT A DOG’.

Draft of poem ‘Old Deuteronomy’ by T S Eliot in a letter from Eliot to Alison Tandy, dated 15 November 1937

Afterlife

The popularity of Old Possum’s cats did not end with the book and its string of reprints. It was successfully adapted into other media. In 1954 the composer Alan Rawsthorne set six of the poems in a work for speaker and orchestra entitled Practical Cats. Recordings survive of its successful stage presentation.

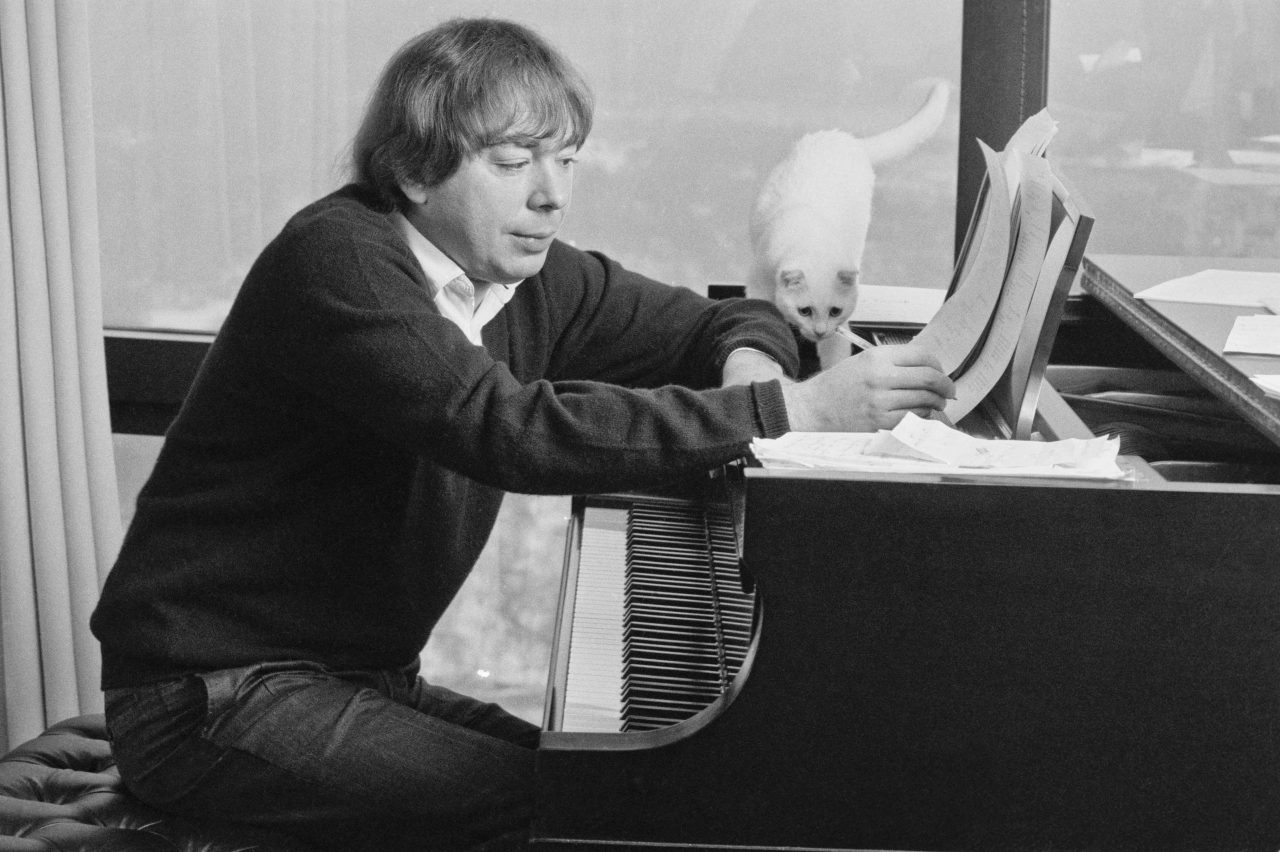

The most famous adaptation has been Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats which had a record-breaking run following its launch on London’s West End stage and New York’s Broadway in 1981 and 1982.

Eliot’s estate, presided over by his widow, Valerie, demanded that the poet’s own words – not some paraphrase or script – be used by Lloyd Webber. Grizabella, excluded from the book version, was added, using an unpublished draft. Few children have found it too ‘sad’ to watch.

Lloyd Webber’s version narrativises the poems around the band of Jellicles, providing a storyline rather than presenting a series of what would have been stilted solo performances. The stage version was filmed in 1988.

Eliot died long before the stage version, and it is pleasant to speculate what he would have made of it. If it entertained children, and amused adults, Old Possum would, one can plausibly assume, have heartily approved and, like most of us, would have left the theatre humming Lloyd Webber’s catchy songs.

Contributor:John Sutherland

The text in the article is © John Sutherland. It may not be reproduced without permission.

相关文章

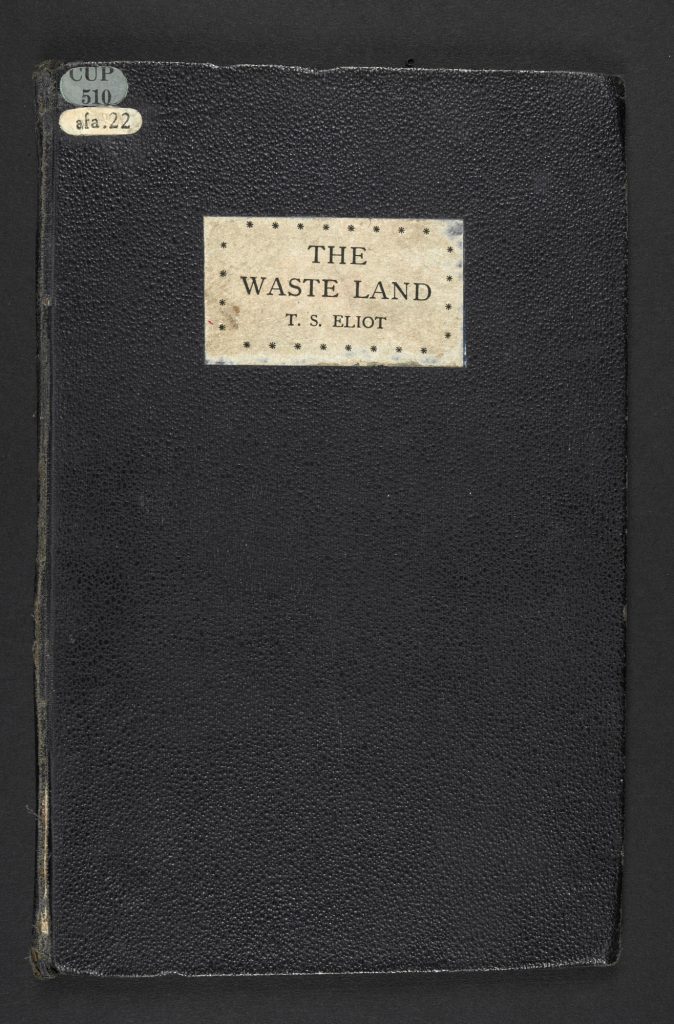

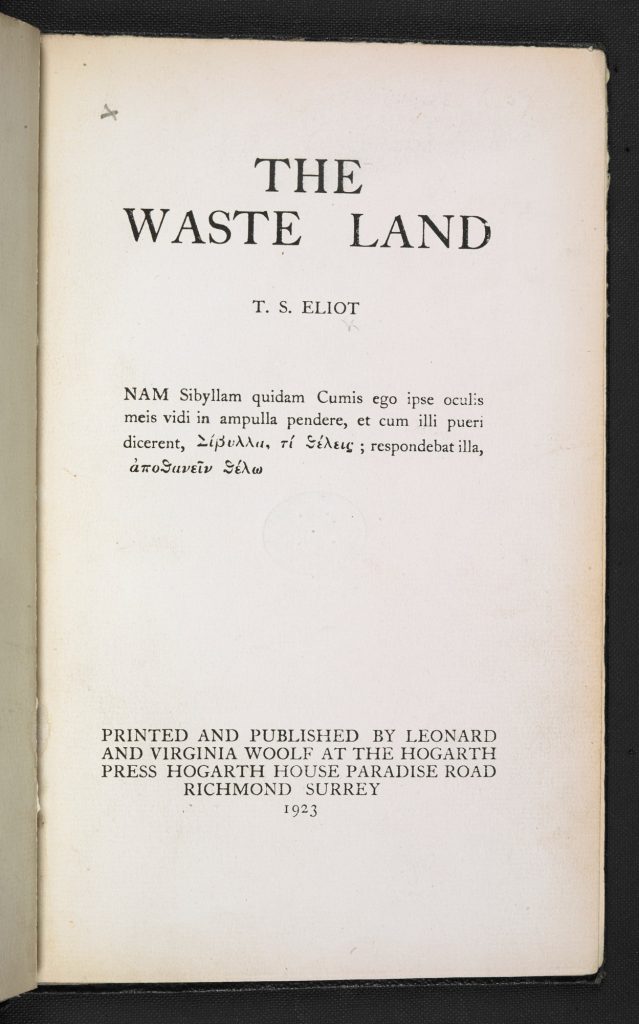

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land

The Waste Land is arguably the most influential modernist poem of the 20th century. Across the poem's five sections, Eliot presents a bleak picture of the landscape of the contemporary world and its history.

Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense

Quirky and infectiously absurd, Edward Lear’s ‘nonsense’ writings have been treasured by generations of children, who adore their humour and wild surrealism. His two-volume collection of poems and drawings, A Book of Nonsense, was so successful that it has never been out of print since.

Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories

Rudyard Kipling told his children gloriously fanciful tales of how things in the world came to be as they are. He wrote them down for publication as the Just So Stories in 1902, just three years after the tragic death of his daughter for whom they had first been invented.