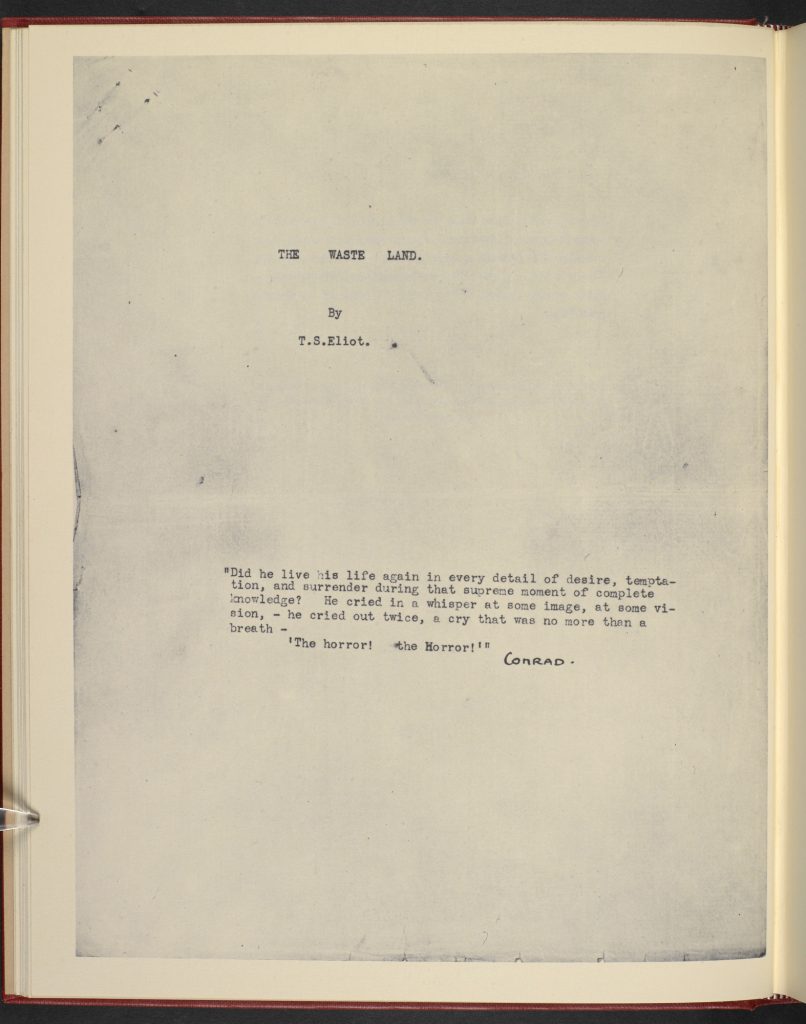

Presences in The Waste Land

T S Eliot‘s The Waste Land is full of references to other literary works. Seamus Perry takes a look at four of the most important literary presences in the poem: Shakespeare, Dante, James Joyce and William Blake.

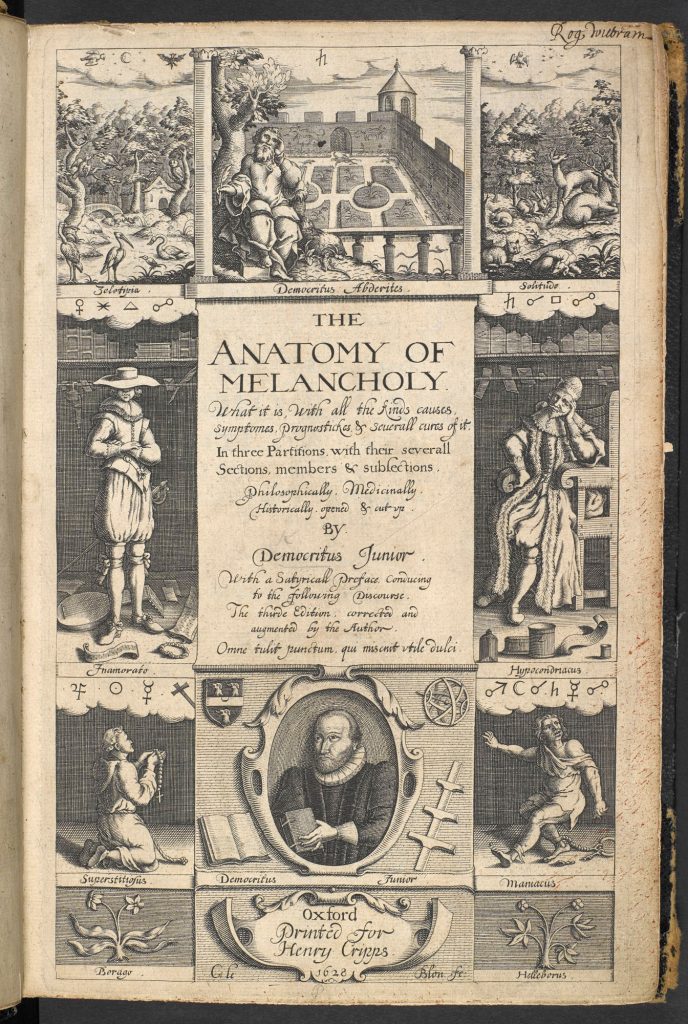

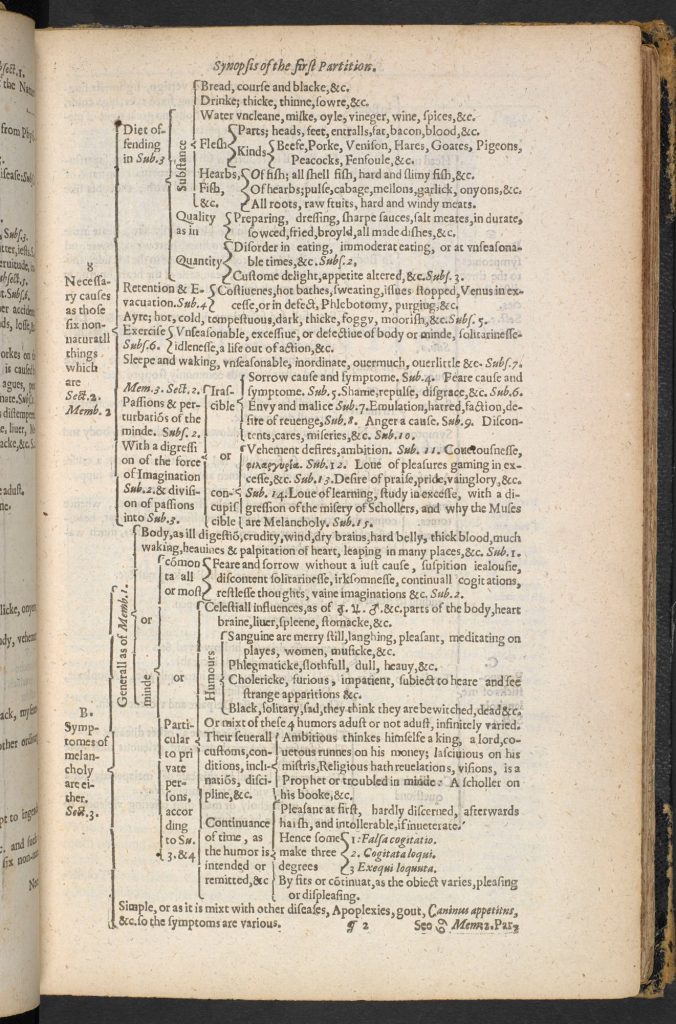

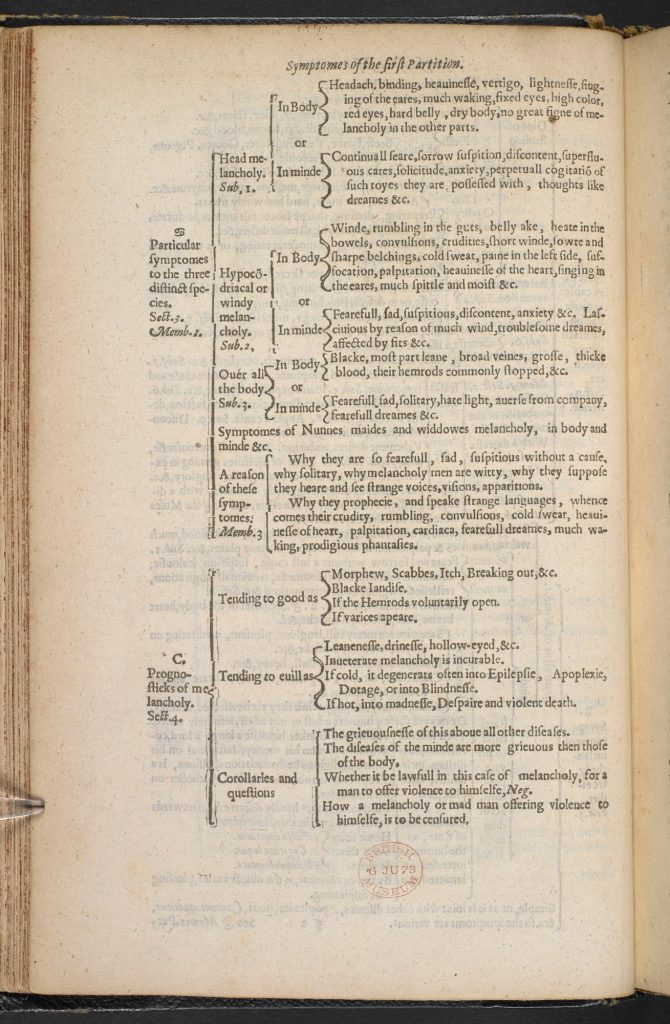

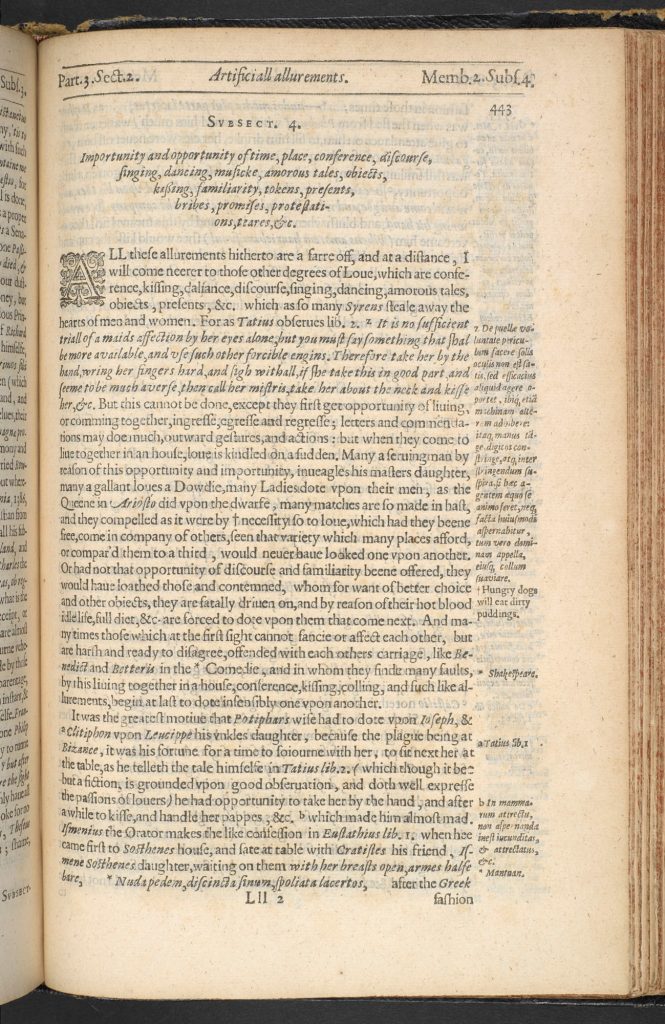

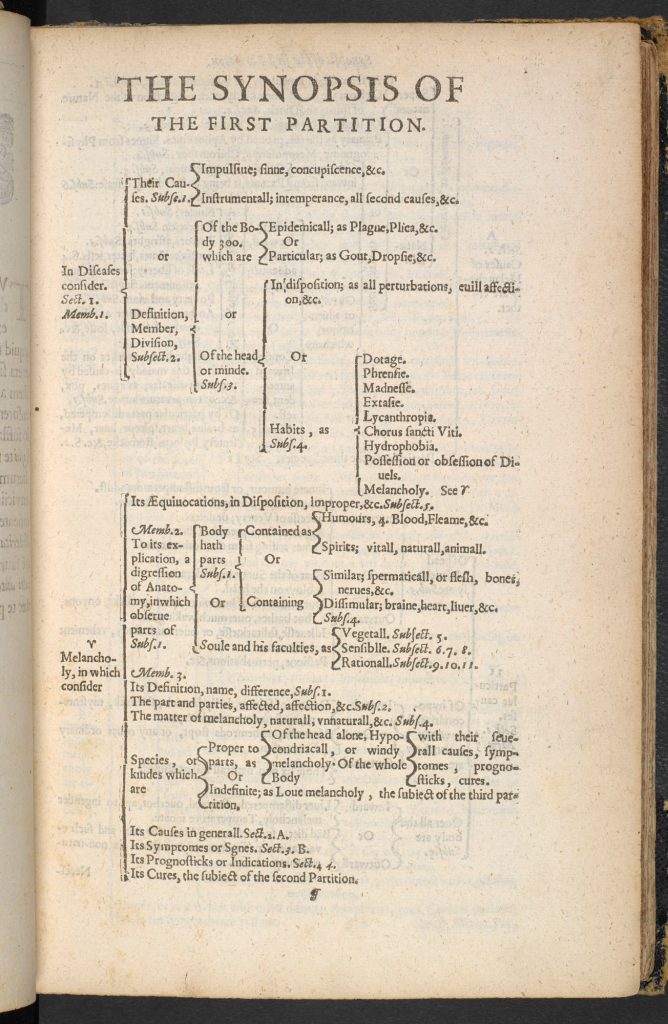

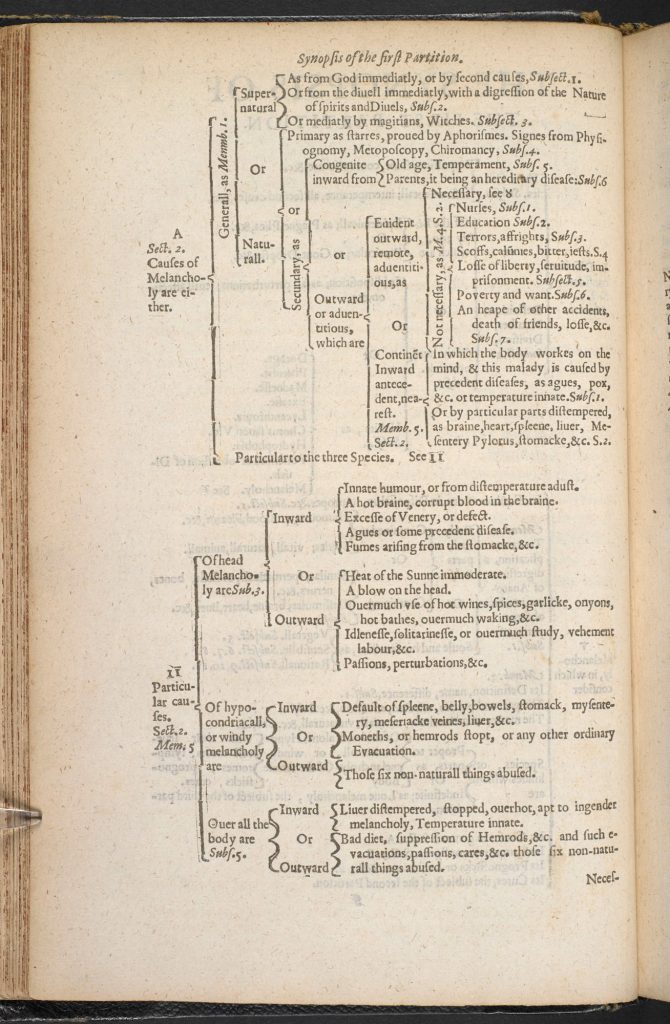

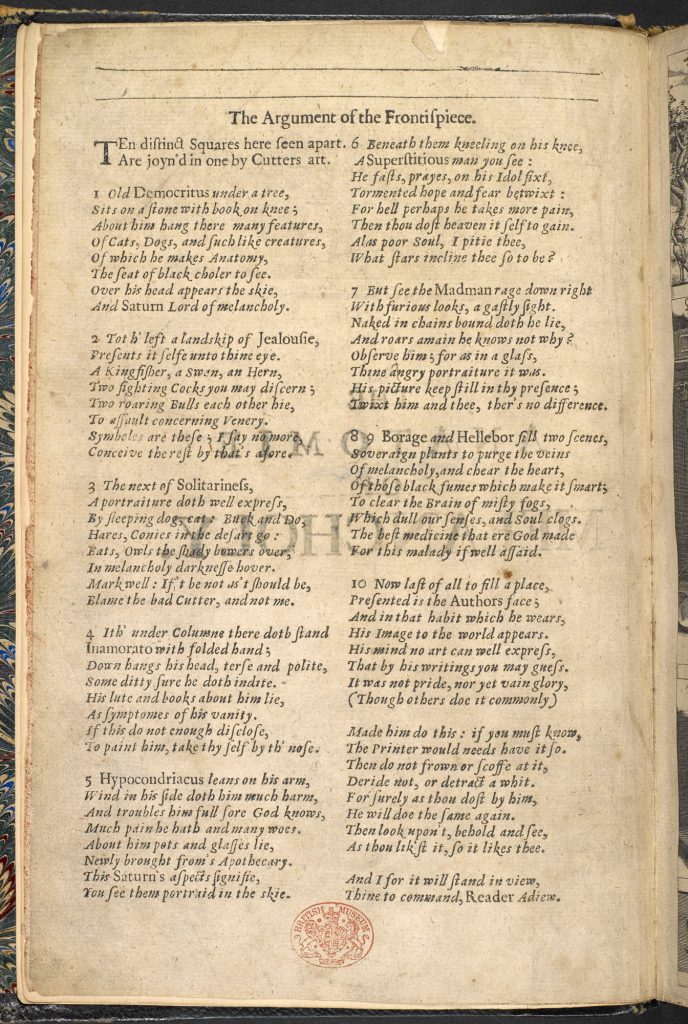

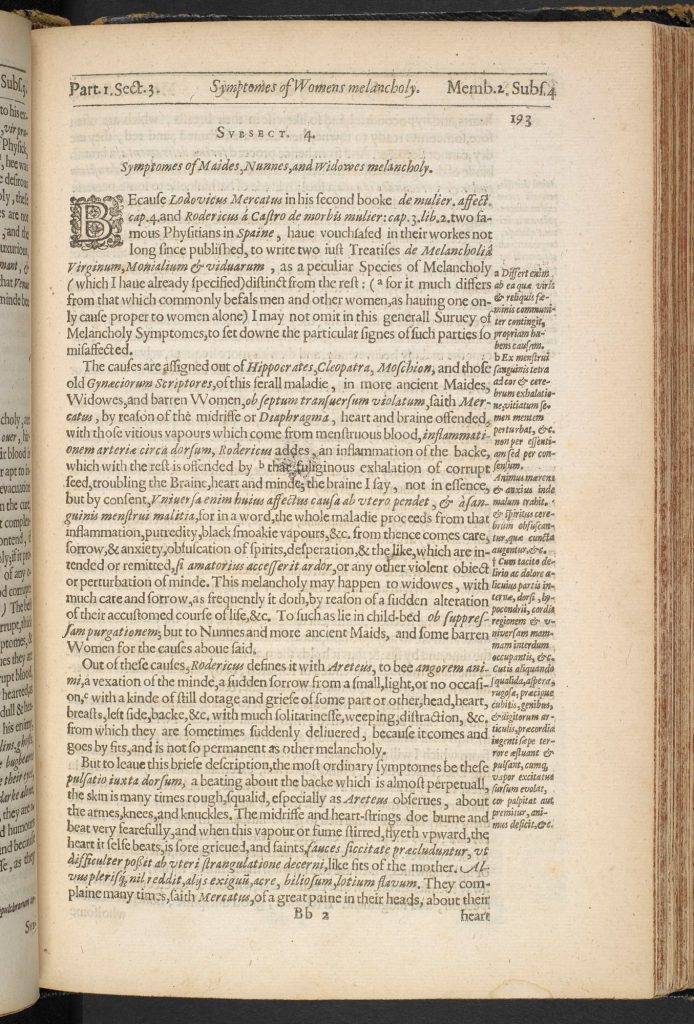

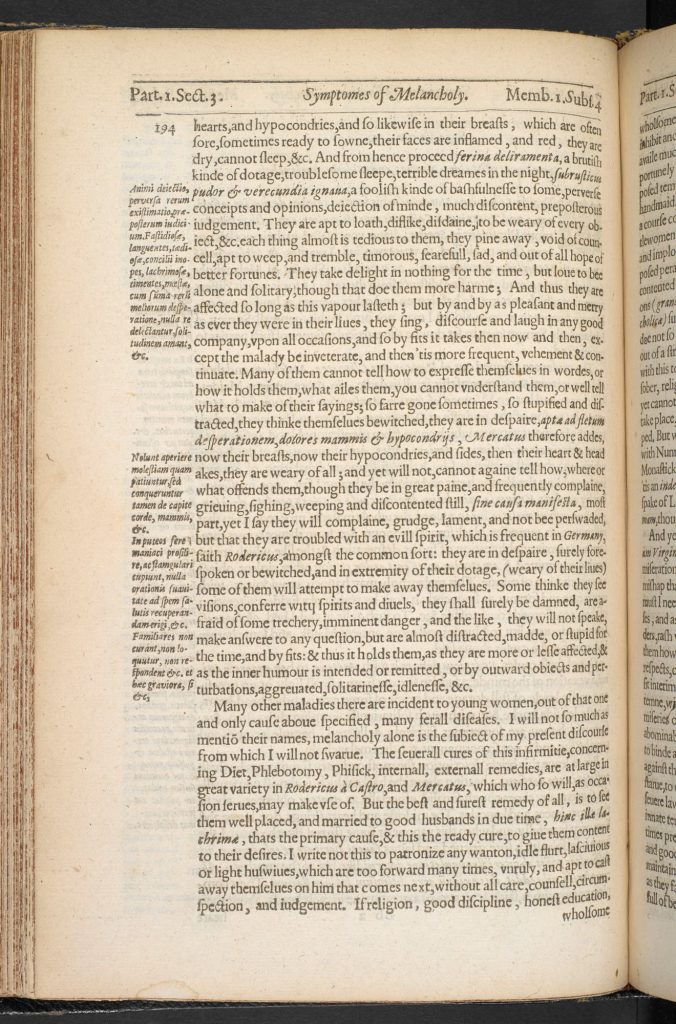

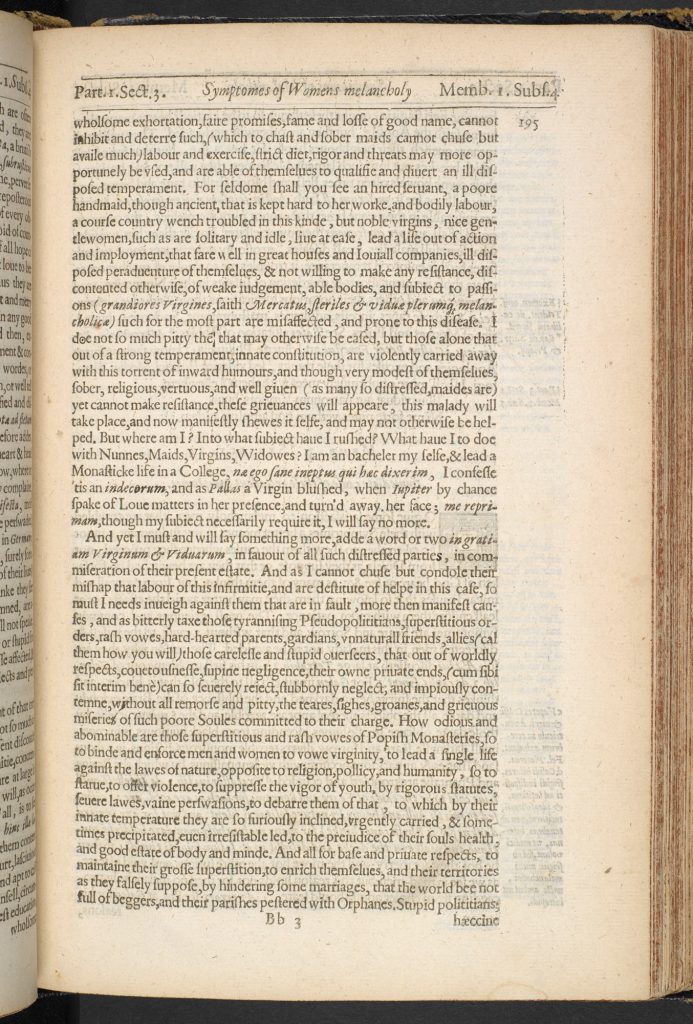

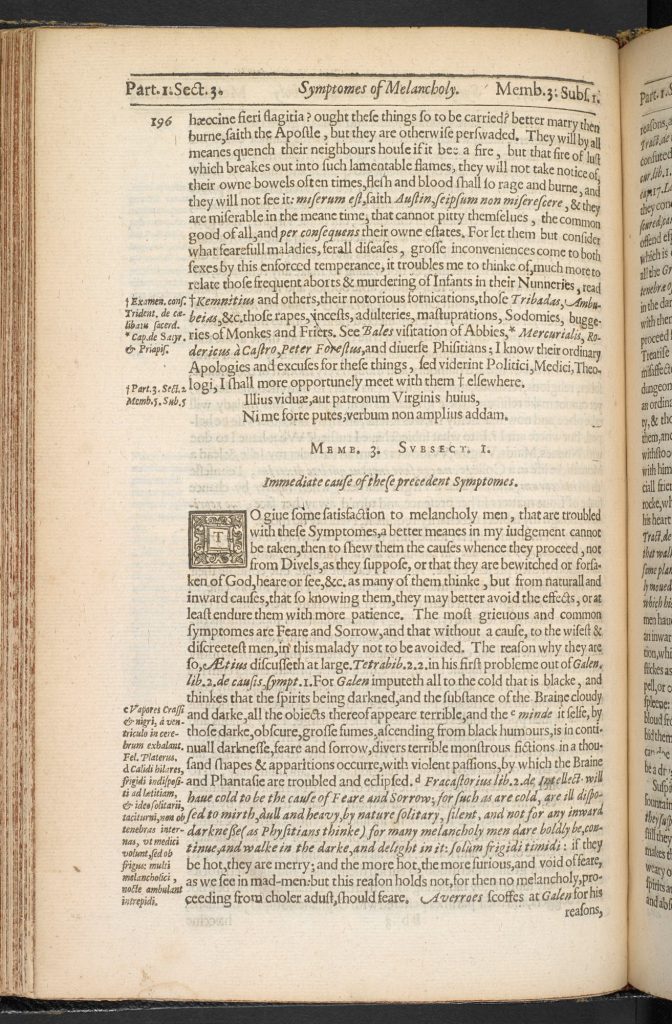

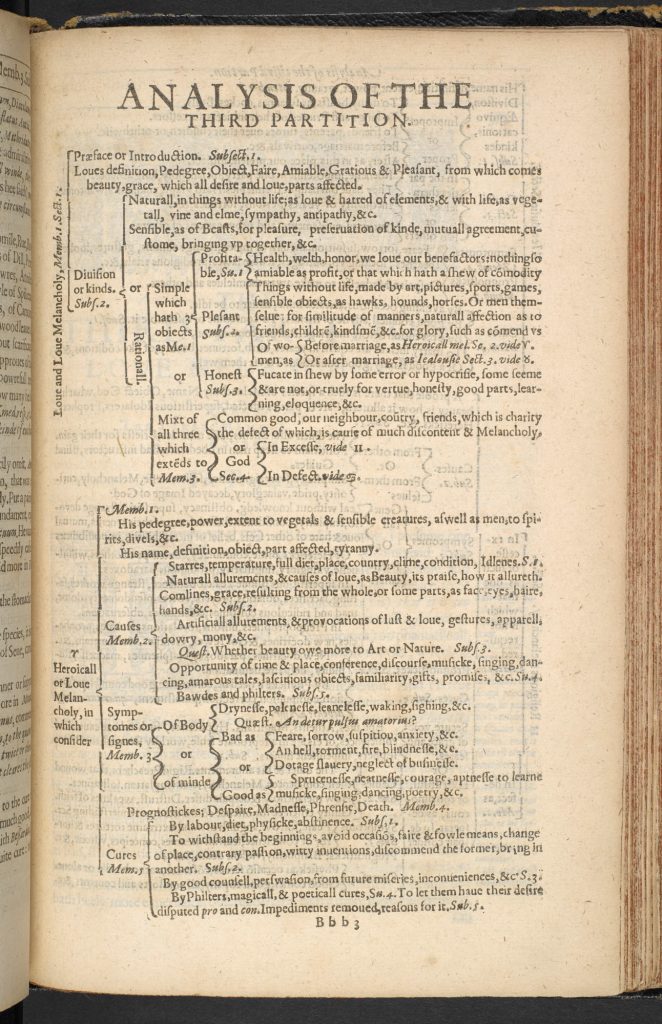

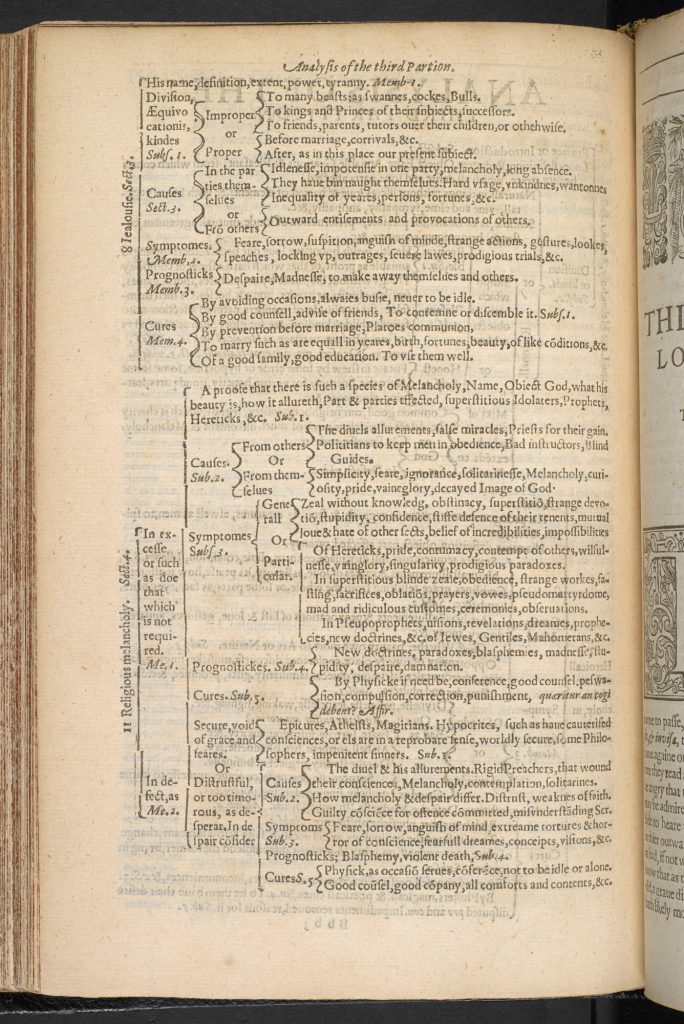

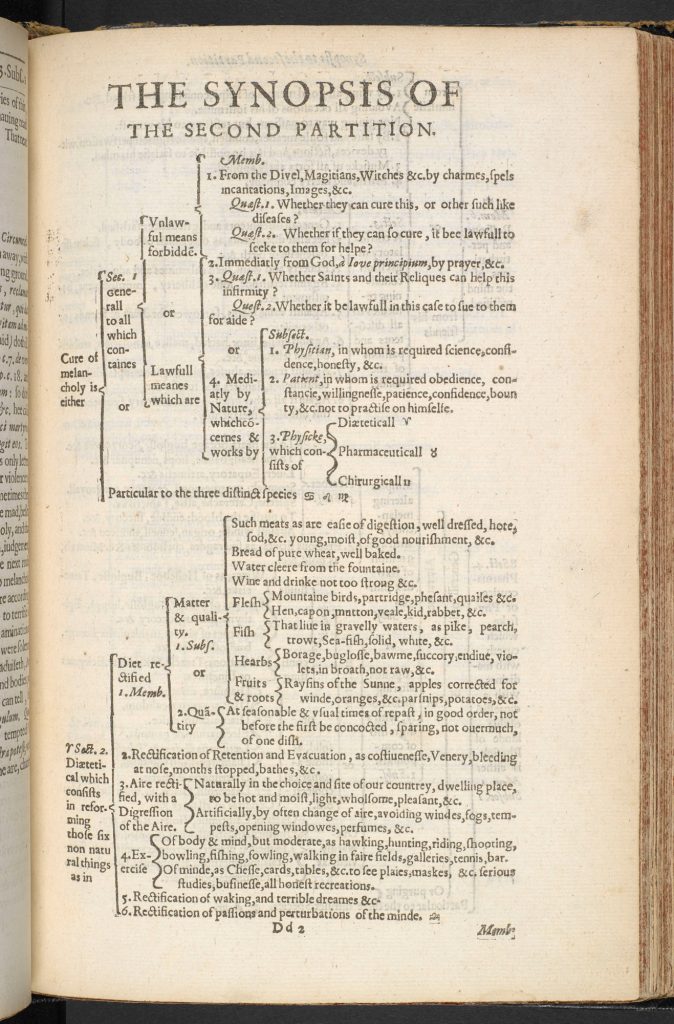

One of T S Eliot’s friends, Conrad Aiken, wrote a review of The Waste Land which was published under the title ‘An Anatomy of Melancholy’. When Eliot heard he was extremely cross because, as he said to Aiken, ‘There is nothing melancholy about it!’ Aiken defended himself: ‘The reference, Tom, was to BURTON’s Anatomy of Melancholy, and the quite extraordinary amount of quotation it contains!’ Of course the poem is not really very much like The Anatomy of Melancholy, which is a 17th-century compendium of contemporary learning about almost everything; but Aiken was right to draw his readers’ attention to one of the poem’s most striking innovations: the intensity and intricacy of its relationship with other works of literature – sometimes a matter of quoting them, sometimes of misquoting them or gesturing towards them. All texts exist within the world of other texts, literary and otherwise; but Eliot’s poem to an unprecedented extent establishes itself as what it is through thoughts of what other people’s poems are.

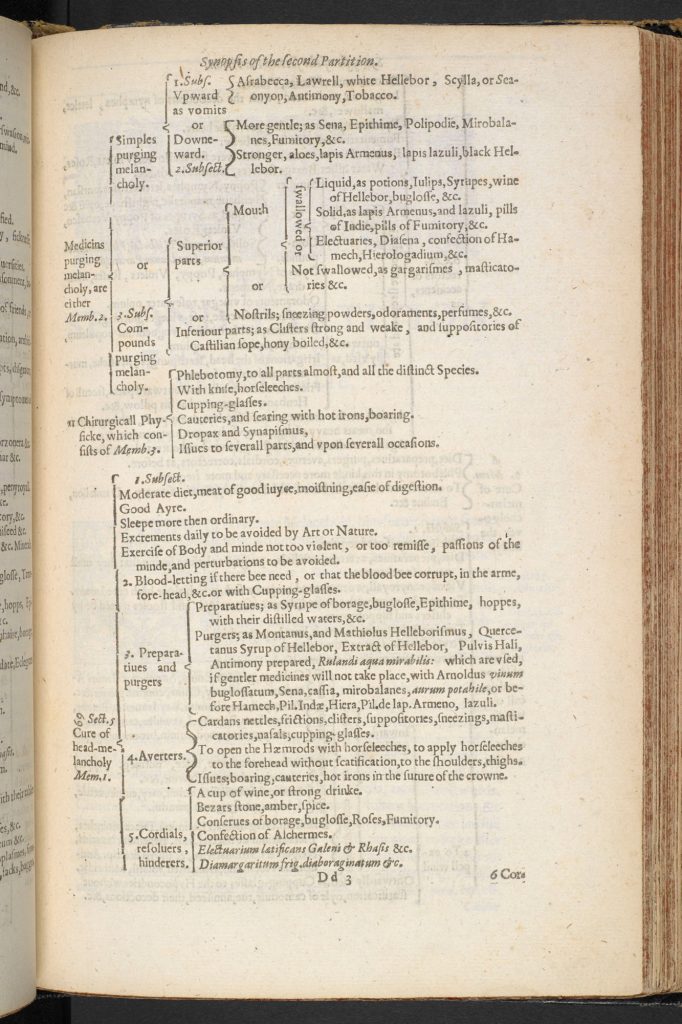

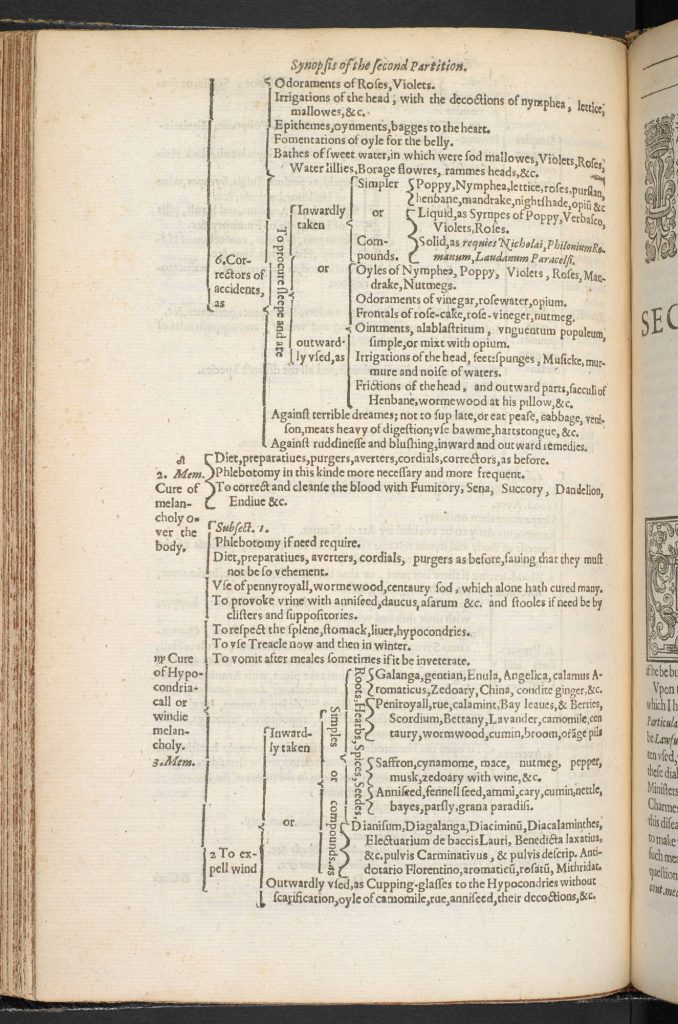

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

T S Eliot’s The Waste Land extensively quotes from the The Anatomy of Melancholy, a 17th century text by Robert Burton.

Dozens of authors and texts accompany the poem: Eliot’s own notes identify many of them, and dozens of other allusions have been suggested since. The poem resounds with things other than literature too: at different moments it tunes in to Wagnerian opera, rag music, Eastern scripture, nursery rhymes, the call of the pub landlord at closing time; and occasionally it sounds noises beyond the human too – the cries of birds (a thrush, a cockerel) and the rolling of thunder. Eliot wrote strikingly in his prose works about the way that the totality of a society’s life, high and low, properly comes together to constitute its complete ‘culture’; and although the society portrayed in The Waste Land is anything but coherent and whole, as Eliot thought a healthy culture required, the spread of the poem’s range speaks to his abiding preoccupation with the way that very different sorts of fragmentary experience may co-exist fruitfully as parts of a single, larger, inclusive sort of experience. The canon of Western literature is only one of the things that is drawn into the difficult synthesis of The Waste Land, but it is one of the most important; and of all the great authors present in the poem, four contribute more than most to the ways in which Eliot uses the recollection of pre-existing texts to create new kinds of meaning: they are Shakespeare, Dante, Joyce and Blake.

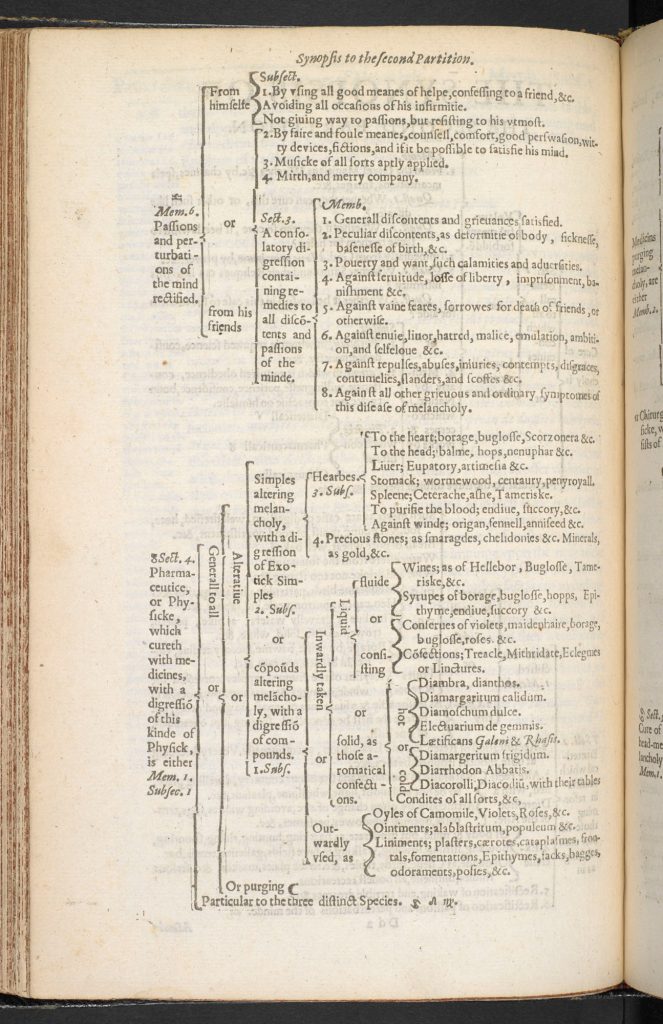

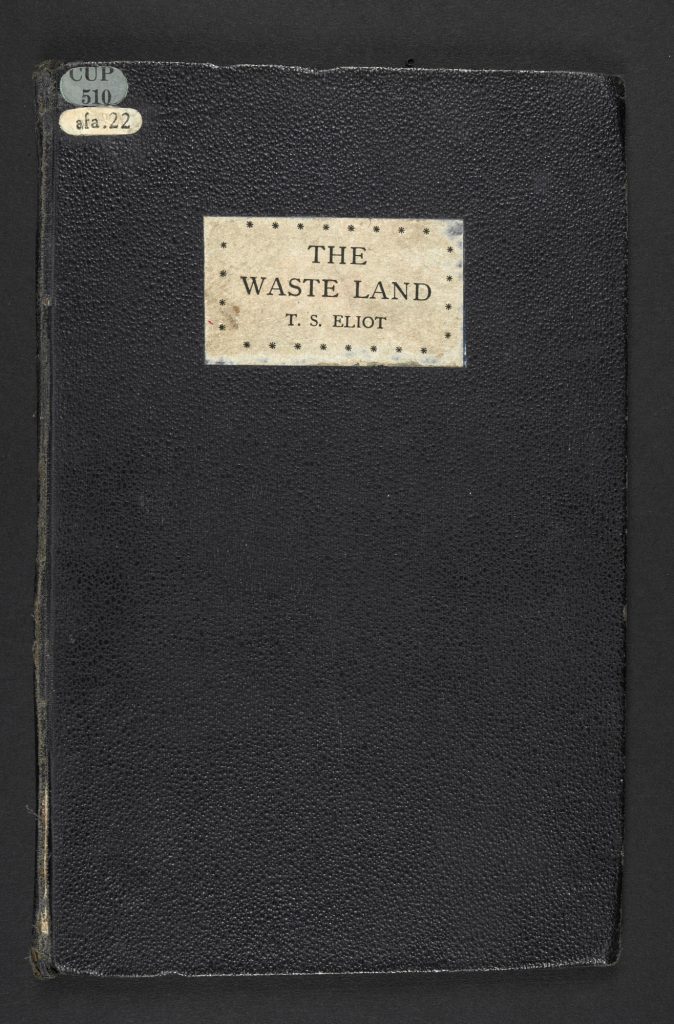

Front cover from the Hogarth Press edition of T S Eliot’s The Waste Land, 1923. The poem was first published in America in 1922.

Shakespeare

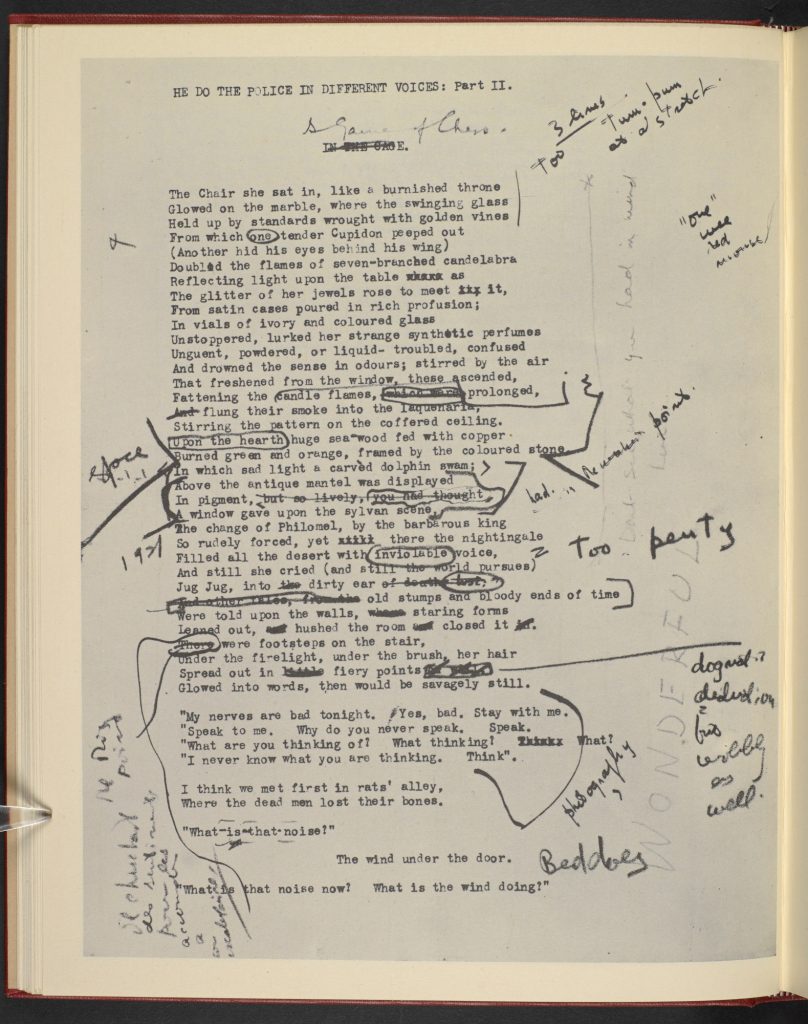

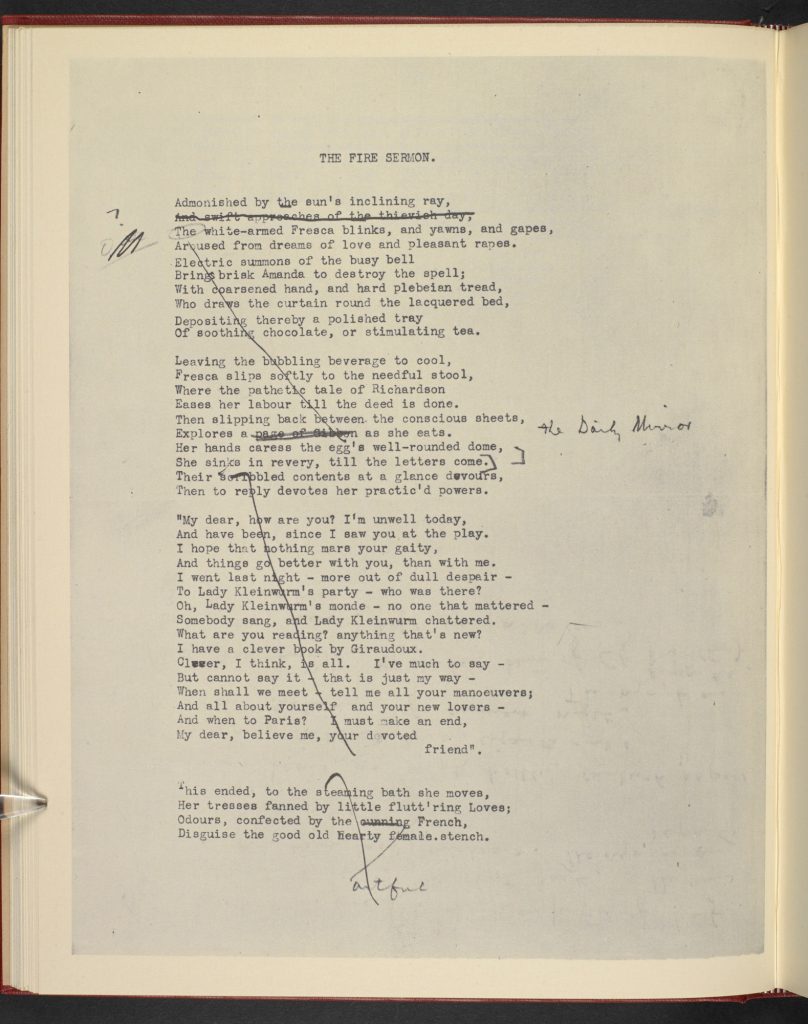

Four plays inhabit the imagination of The Waste Land with particular presence: Antony and Cleopatra, Hamlet, Coriolanus and The Tempest. The ancient clash of empires which shapes the erotic tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra anticipates the poem’s modern interweaving of European war and personal catastrophe, a parallel which the opening lines of Part 2 brings to the surface: the faltering rhythm of ‘The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne’, mishears Enobarbus’s great description of Cleopatra on her sumptuous royal barge (not ‘Chair’), offering a depleted Cleopatra for diminished times. Much of the poem is preoccupied with suffering of a specifically female kind, and if the archetype of Cleopatra involves a downfall that is at least partly the work of her own hands, then the death and madness of Ophelia, from Hamlet, is more unmitigatedly a portrait of victimhood.

Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

‘The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne’: T S Eliot alludes to Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra in the opening to Part II of The Waste Land.

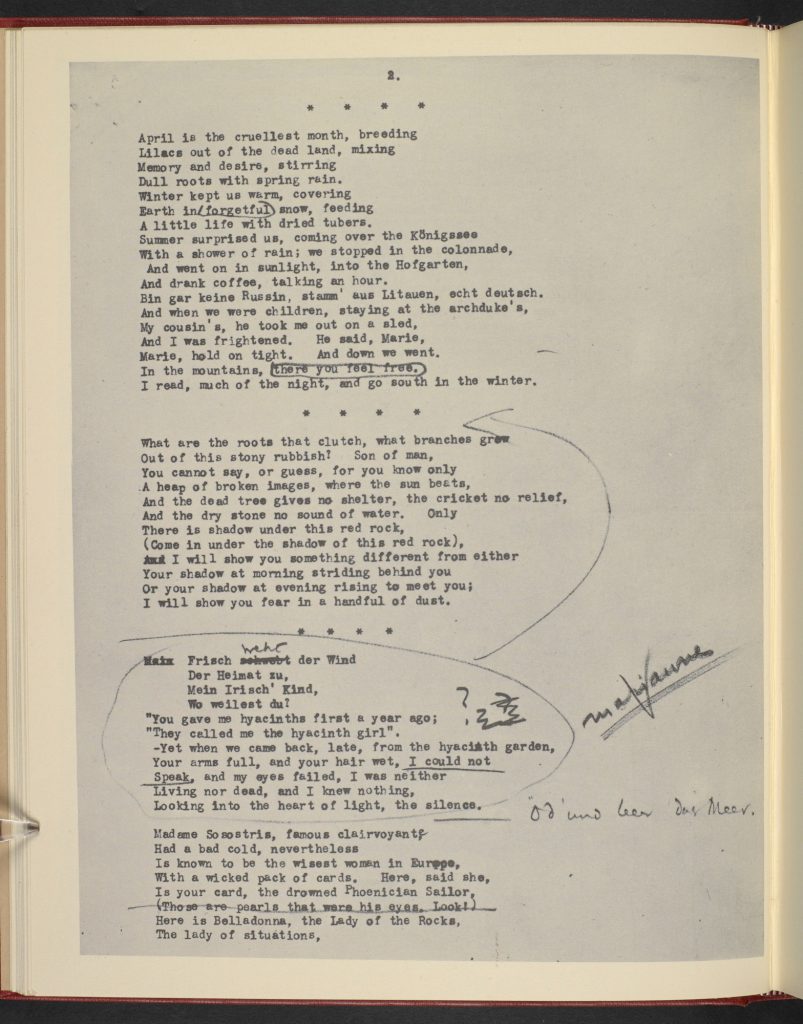

In the last line, the voice of Ophelia, in the play distracted by grief, tunes in with the blurry farewells at closing time. ‘Her speech is nothing’, we are told of Ophelia in Hamlet, ‘Yet the unshaped use of it doth move / The hearers to collection’, which would be a good epigraph for Eliot’s poem, in which unshaped fragments are collected by their hearers to infer meaning. The figure of Coriolanus represents a different element threading through the poem: the precarious imagining, within so much vividly imagined failure, of the scope and conditions of human success. In Part 5, ‘aethereal rumours’ are said to ‘Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus’: the reference brings into the poem’s mind a brutal and deeply unlikeable Roman hero whose violent life comes to an end after a single defining moment; formerly hell-bent on destroying Rome, he finally chooses not to do so after all, but knows the decision will be his ruin. He represents the possibility of morally transformative self-sacrifice, a theme (as in a musical theme) that is also heard whenever The Tempest comes into the airwaves of the poetry: it is Shakespeare’s great romance of reconciliation and renunciation and metamorphosis, and Eliot is haunted especially by a line from one of its songs, describing the imagined aftermath of a drowning (of which the poem has a number) – ‘Those are pearls that were his eyes!’ The possibility of human transformation haunts the poem, but the line suggests, too, an account of its main poetic method: the conjuring of a mass of inherited elements into ‘something rich and strange’.

Dante

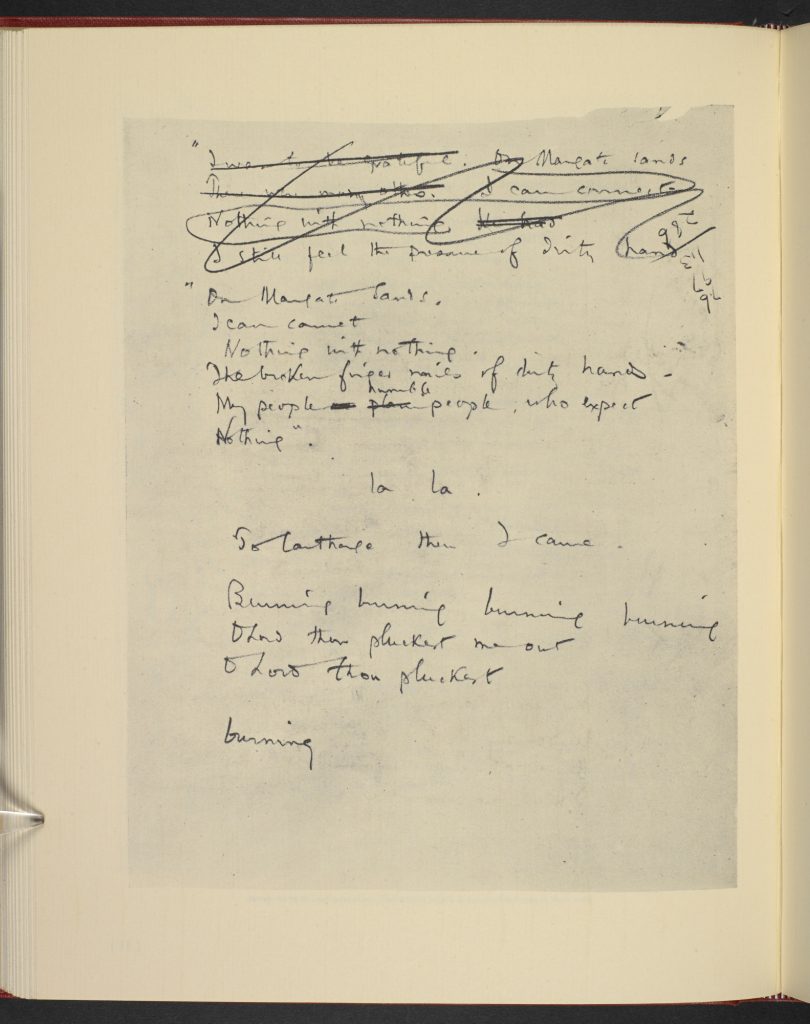

The greatest poem that Eliot wrote before The Waste Land was ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, and the works share a Dantesque perspective on contemporary life. Dante’s Divine Comedy (completed 1320), widely regarded as the central masterpiece of Italian poetry, tracks the journey of its protagonist through Hell and Purgatory, finally arriving at the peak of Paradise. Eliot’s interest in his earlier poems is on the quality of infernal experience as Dante imagines it, the tormenting mixture of ‘Memory and desire’ that Eliot had announced in the opening lines. ‘The ecstasy, with the present thrill at the remembrance of it, is a part of the torture’, wrote Eliot in an essay about Dante published in The Sacred Wood, his critical collection of 1920: ‘For in Dante’s Hell souls are not deadened, as they mostly are in life; they are actually in the greatest torment of which each is capable’. When a crowd flows over London Bridge in Part 1 of The Waste Land, the note brings to mind a parallel we might have dimly felt from the Inferno: ‘I had not thought death had undone so many’. Much later, in the crash of the poem’s last lines, another voice from Dante’s poem emerges, but now from the Purgatorio, the next stage in the journey. It is a voice from the dead who asks to be remembered. Eliot quotes the line that follows the speech: ‘Poi s’ascose ne foco che gli affina’, meaning ‘Then he hid him in the fire which refines them’. The flames of Purgatory are unlike the flames of Hell which otherwise they seem to resemble so closely: they are agonising but their function is not to punish but to amend, for they work purposively to burn away sin and prepare the willing soul (agonisingly) for its progress. It is one of several threads in Part V that show a movement of the spirit, however doctrinally unspecific it might be at this stage in Eliot’s life, towards something other than the perpetuity of the waste.

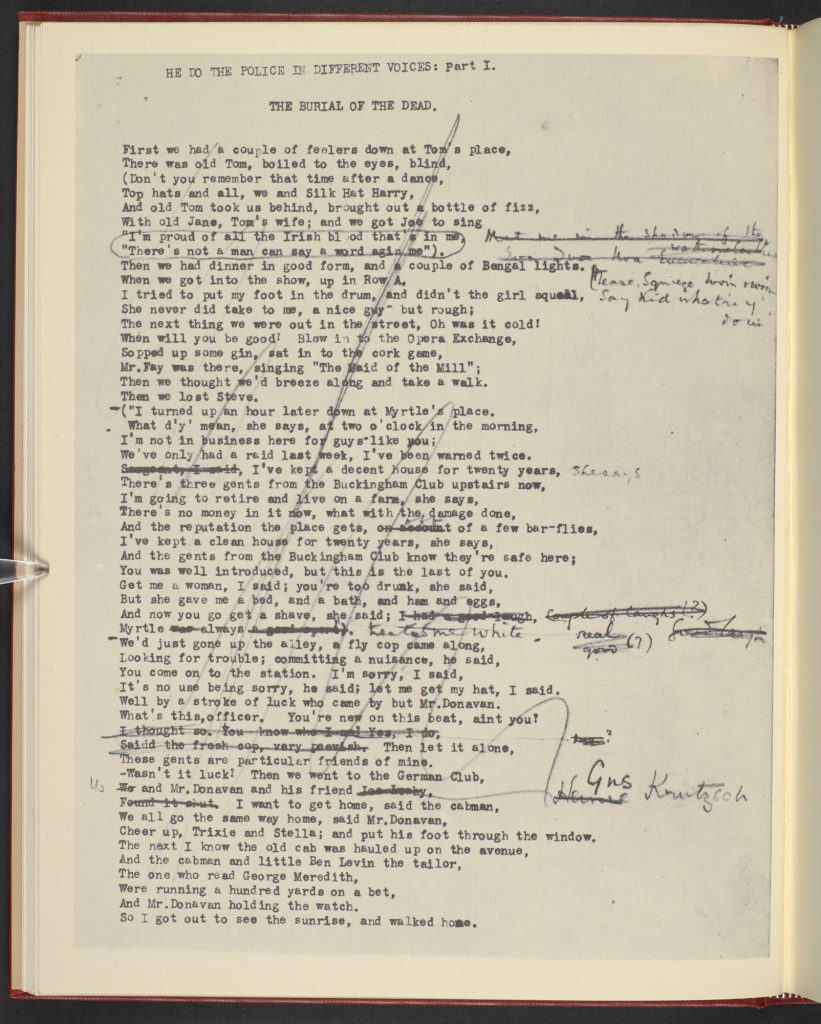

Joyce

The poet Ezra Pound had a decisive shaping impact on the poem, reading it in manuscript and making many suggestions; but of Eliot’s contemporaries it is James Joyce who is the most important presence. The atmosphere of his book of short stories, Dubliners (1914), is one influence: they present a series of case studies in disconnection and human failure which anticipates in many ways the broken relationships of Eliot’s poem. ‘He felt his moral nature falling to pieces’, says Joyce of one of his Dubliners at one point, the normal condition. Eliot’s ear was evidently caught, in particular, by the tragic-comic possibilities implicit in tipsy farewells:

‘Good-night, Gabriel. Good-night, Gretta!’

‘Good-night, Aunt Kate, and thanks ever so much. Goodnight, Aunt Julia.’

‘O, good-night, Gretta, I didn’t see you.’

‘Good-night, Mr. D’Arcy. Good-night, Miss O’Callaghan.’

‘Good-night, Miss Morkan.’

‘Good-night, again.’

‘Good-night, all. Safe home.’

‘Good-night. Good night.’

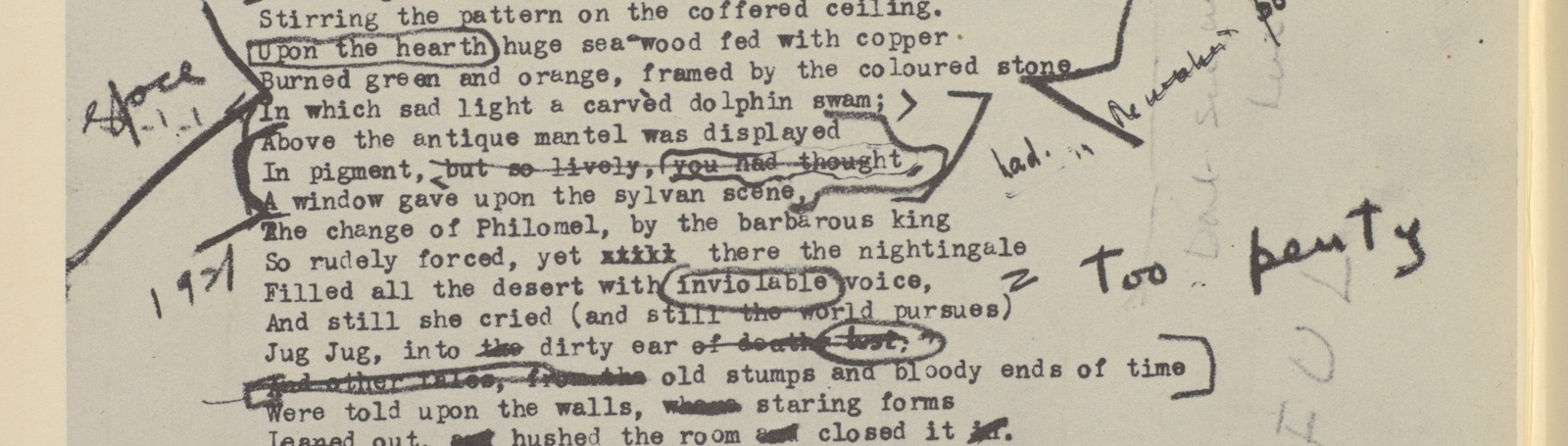

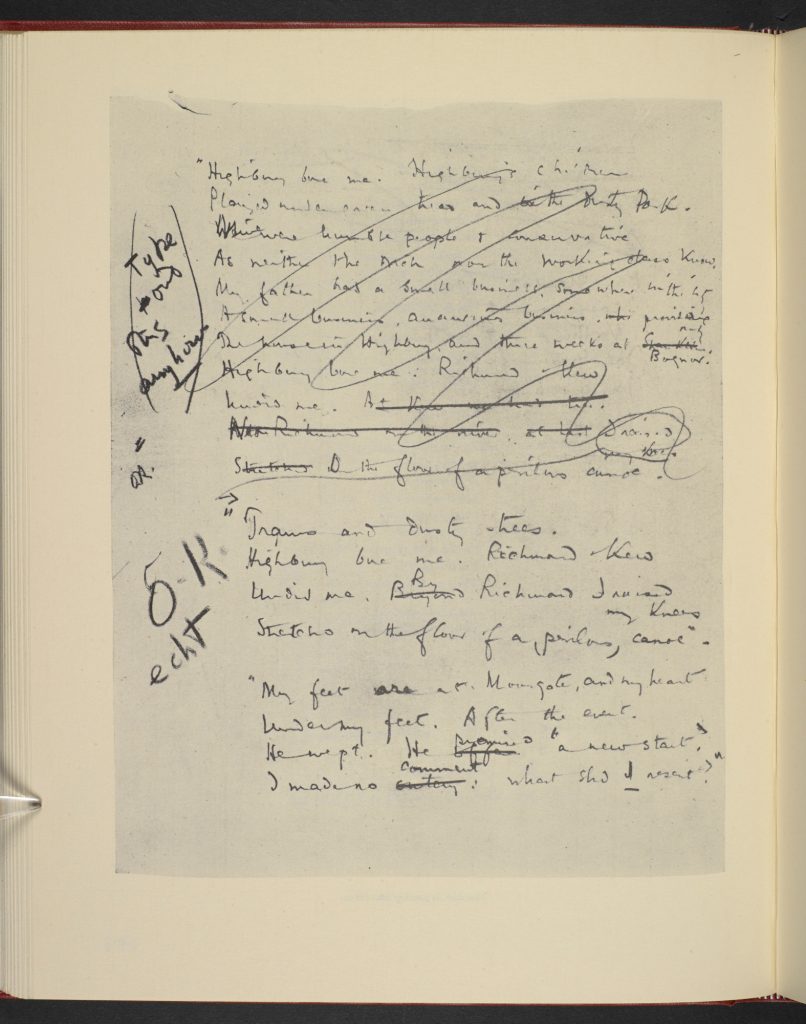

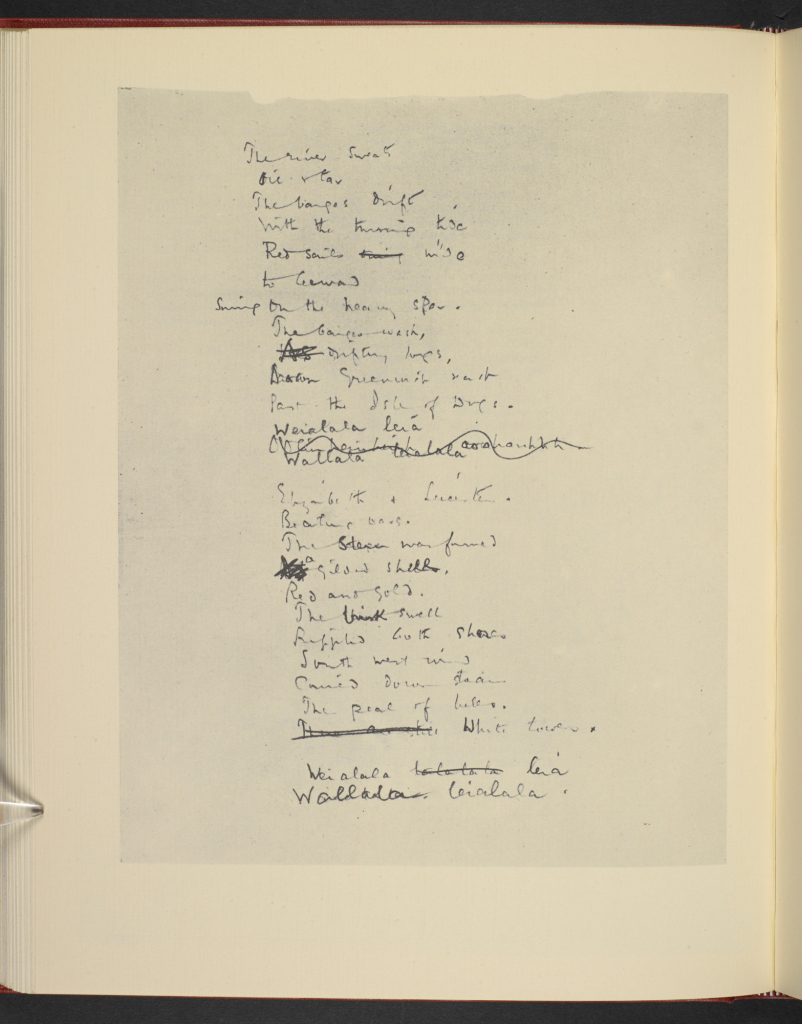

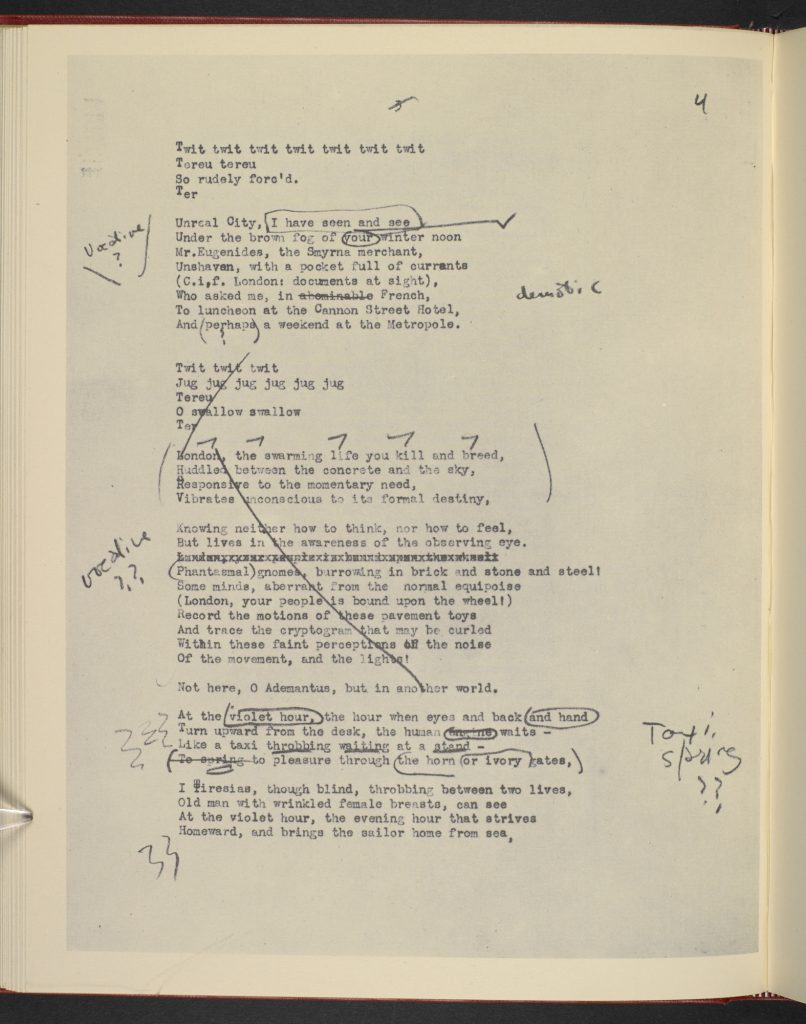

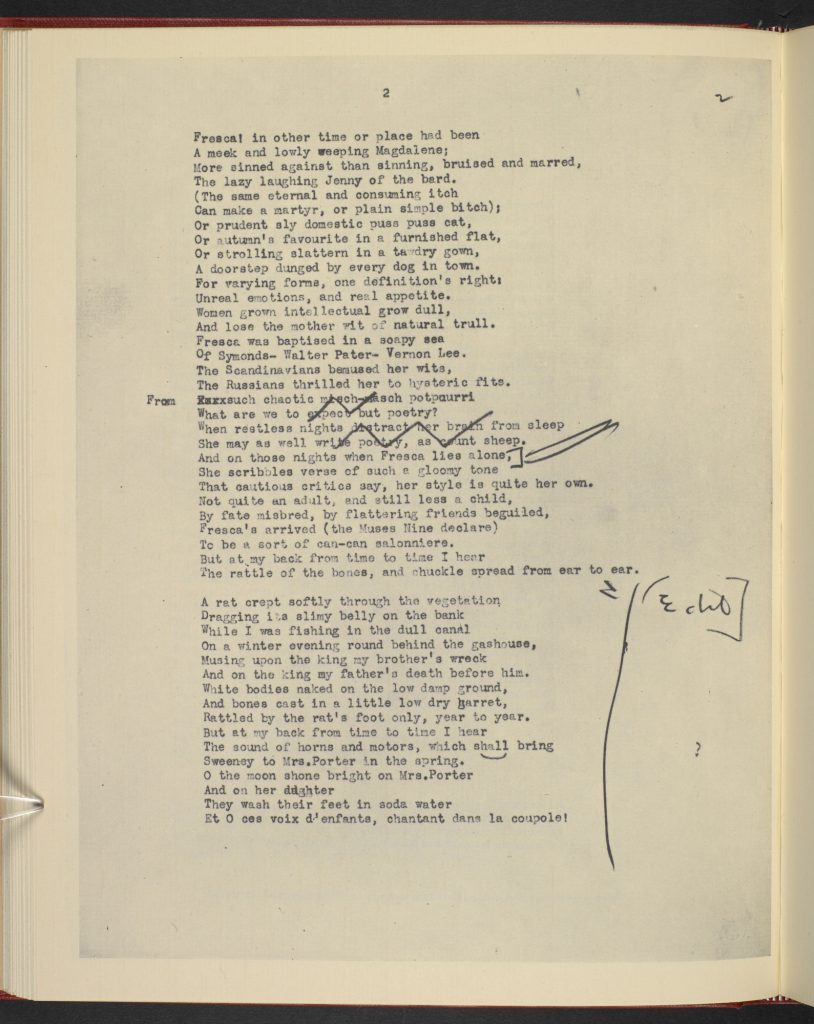

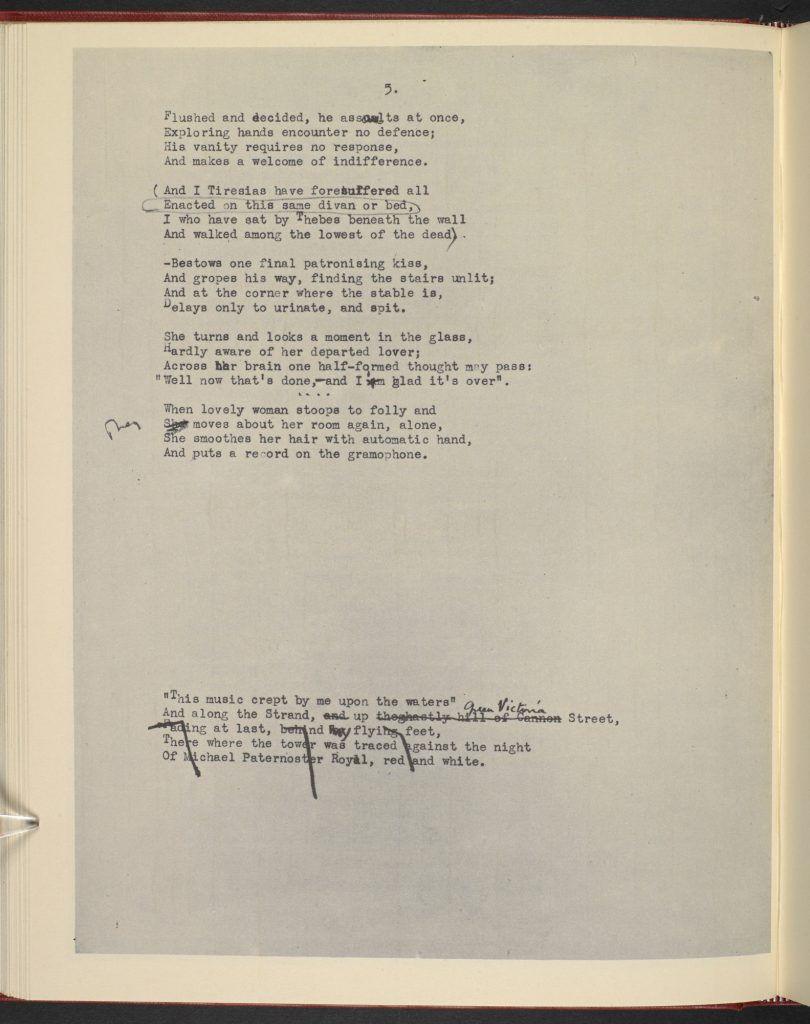

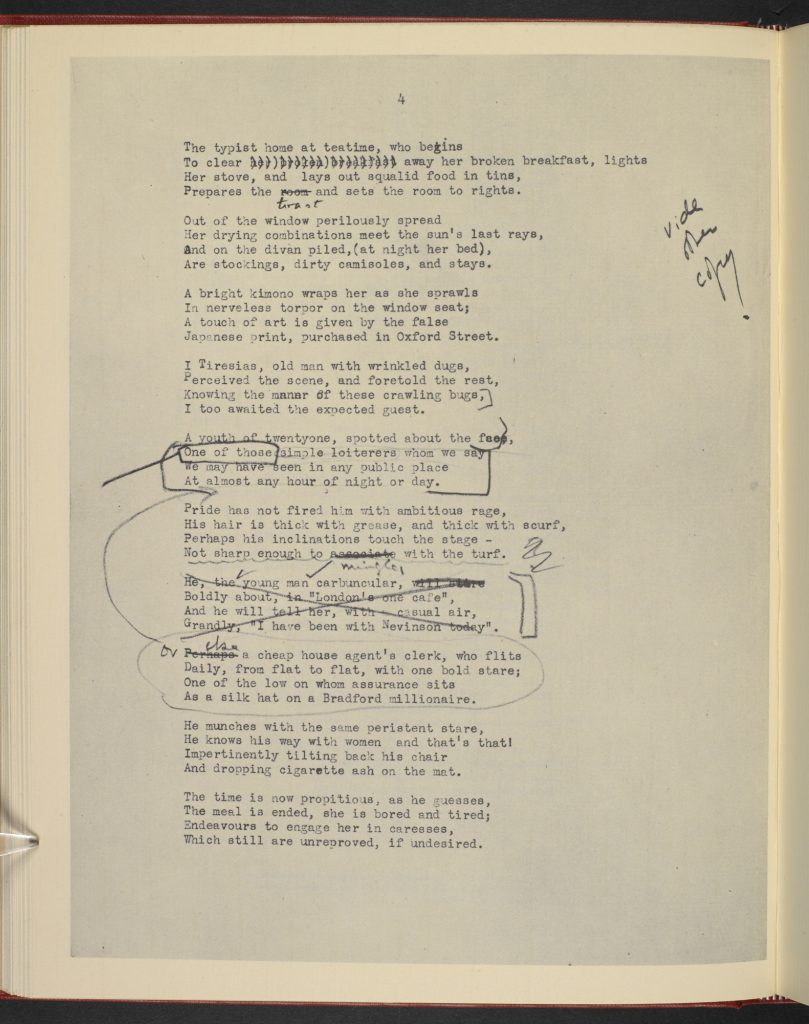

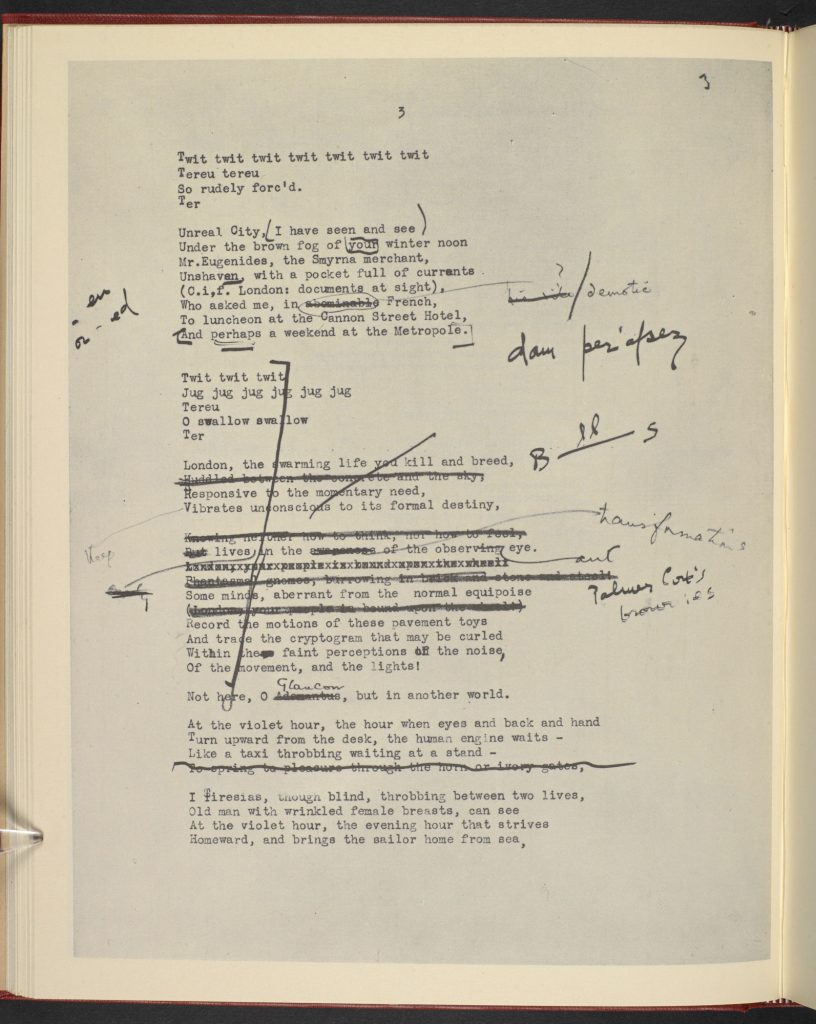

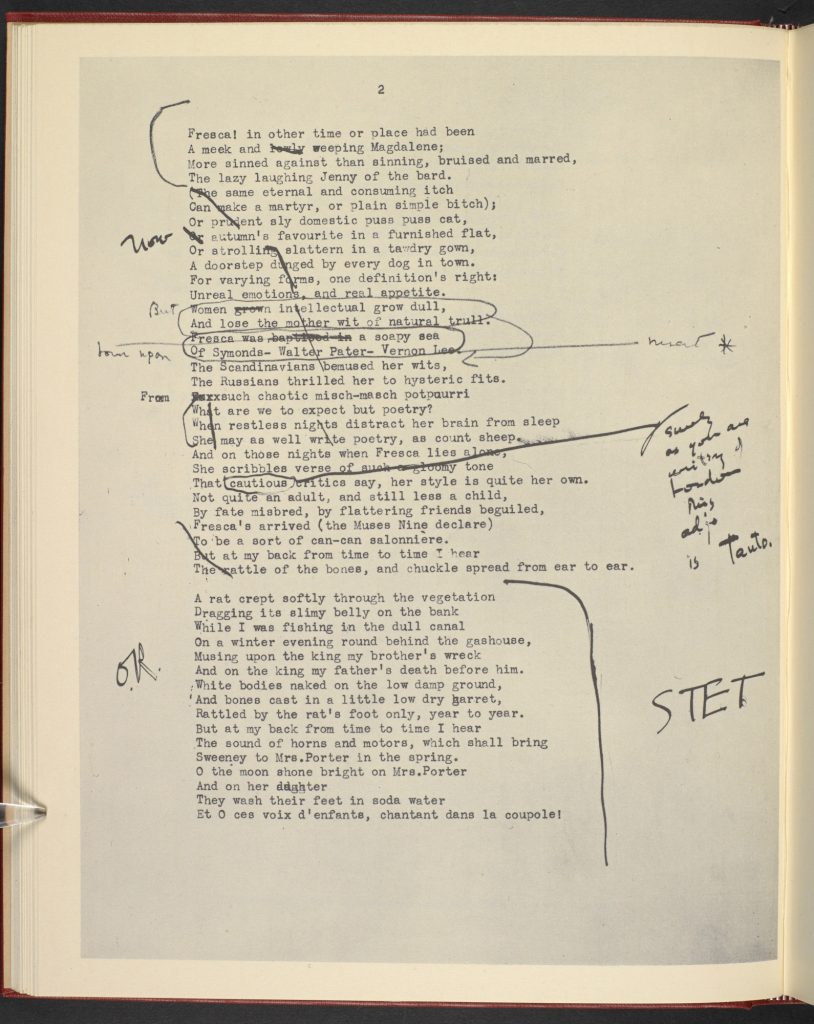

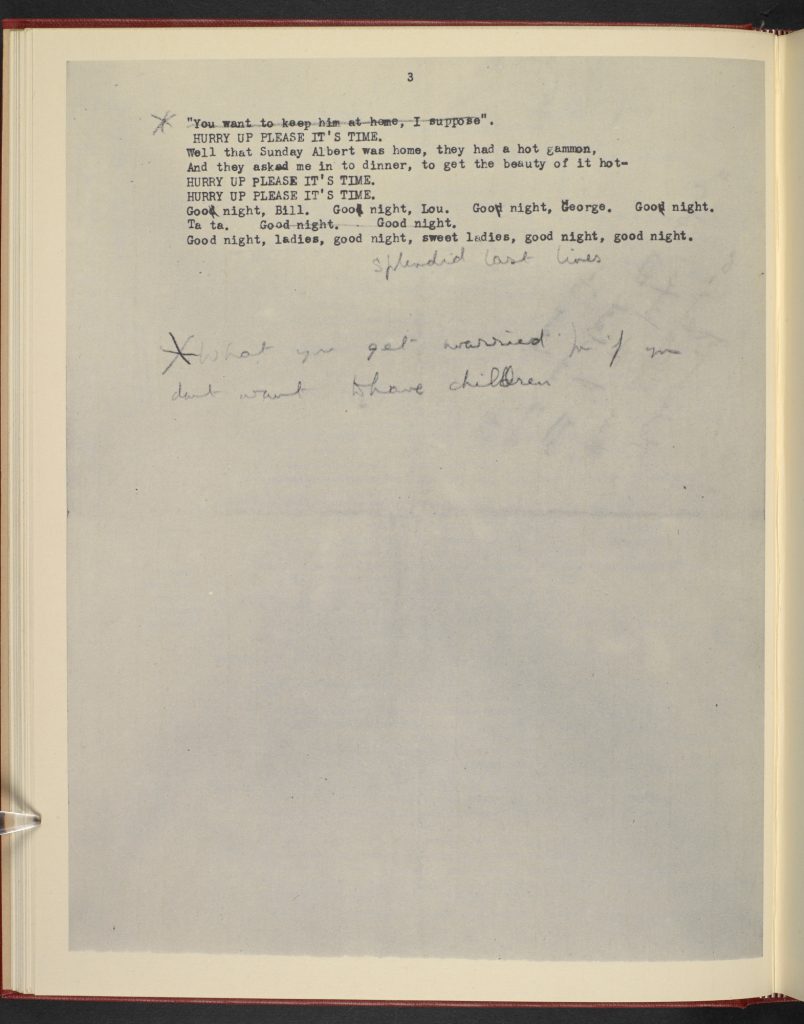

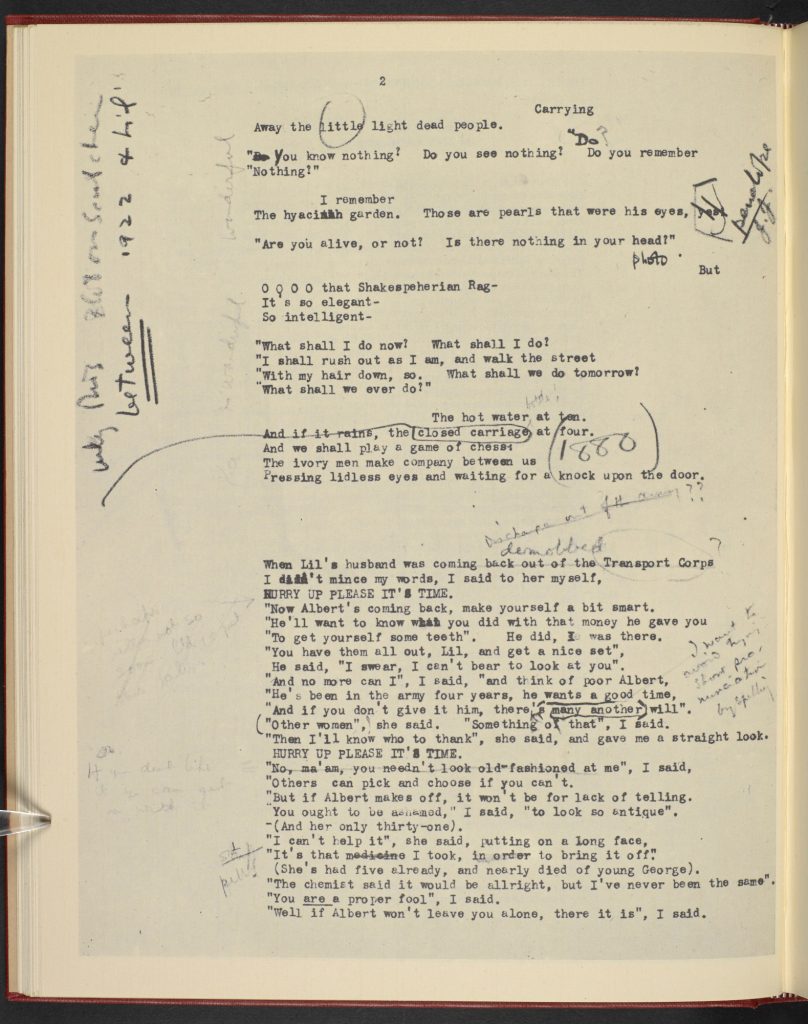

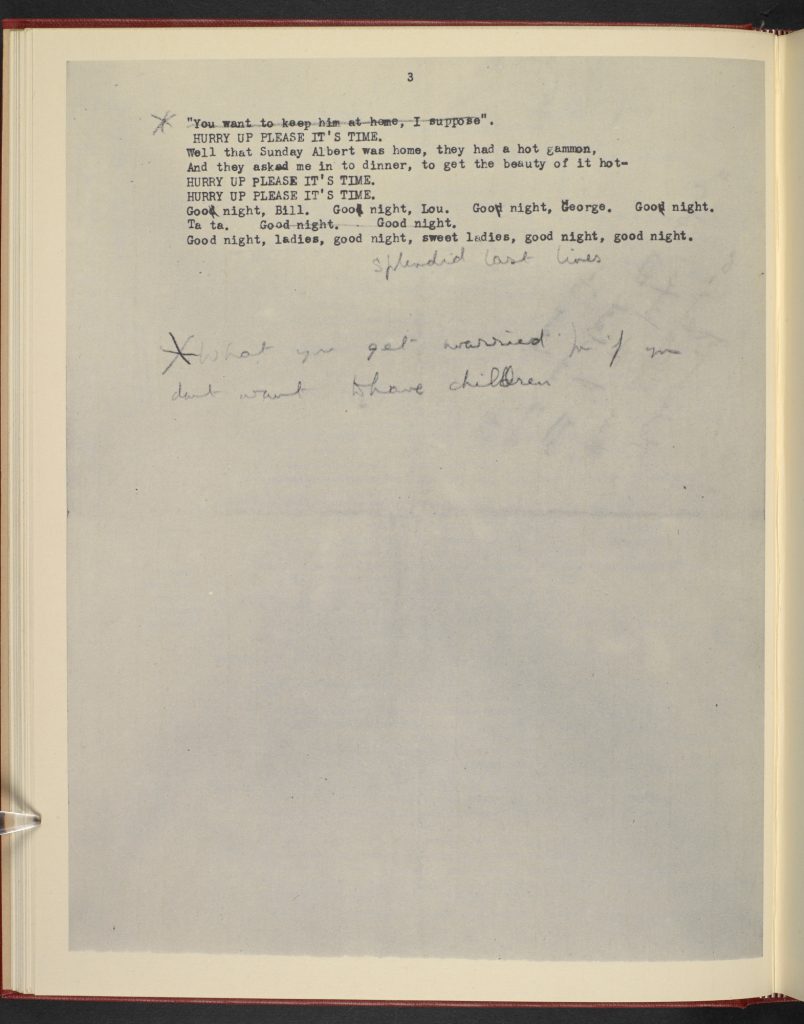

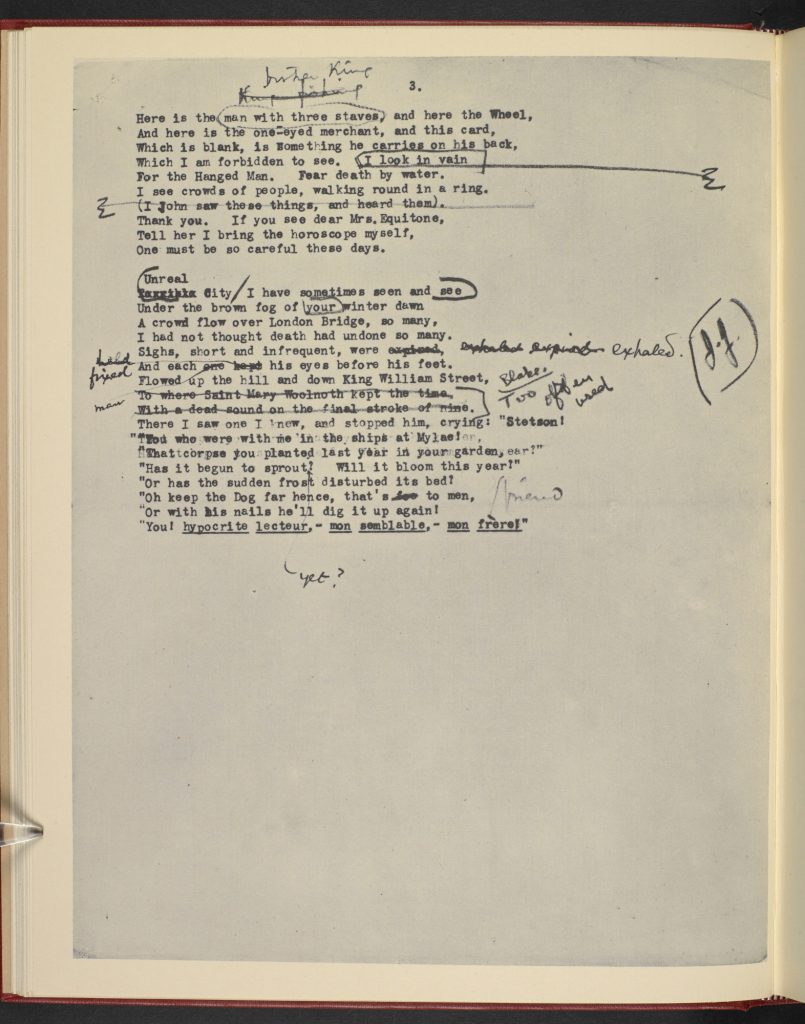

‘Good night, Bill. Good night, Lou. Good night, George. Good night. / Ta ta. Good night. Good night’: T S Eliot’s manuscript revisions to the close of Part II of The Waste Land, a scene which echoes the tipsy farewells in James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914).

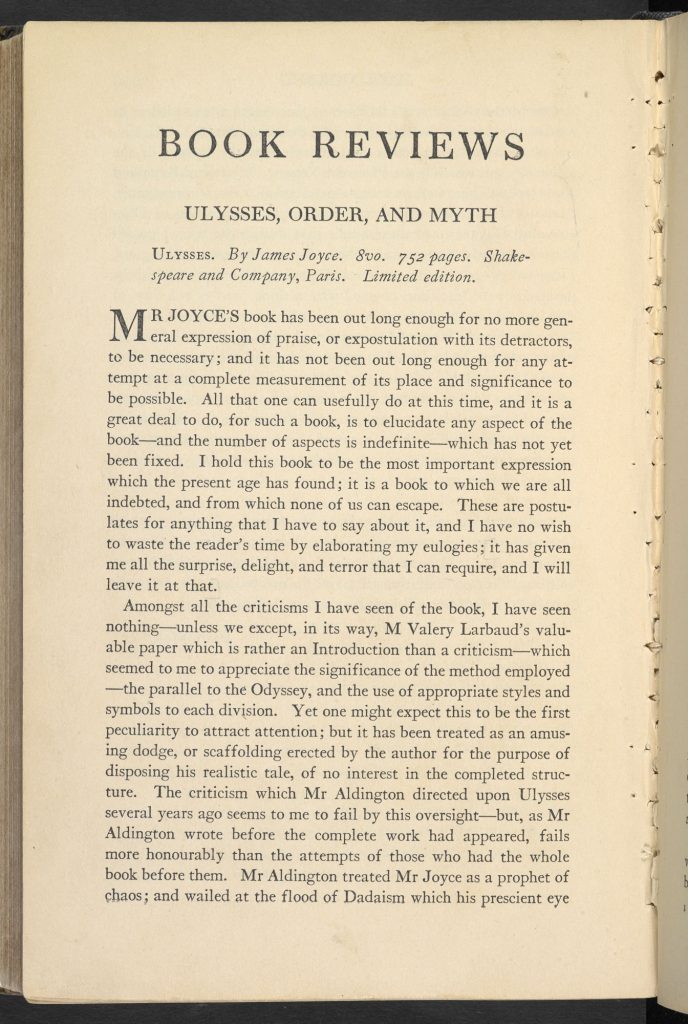

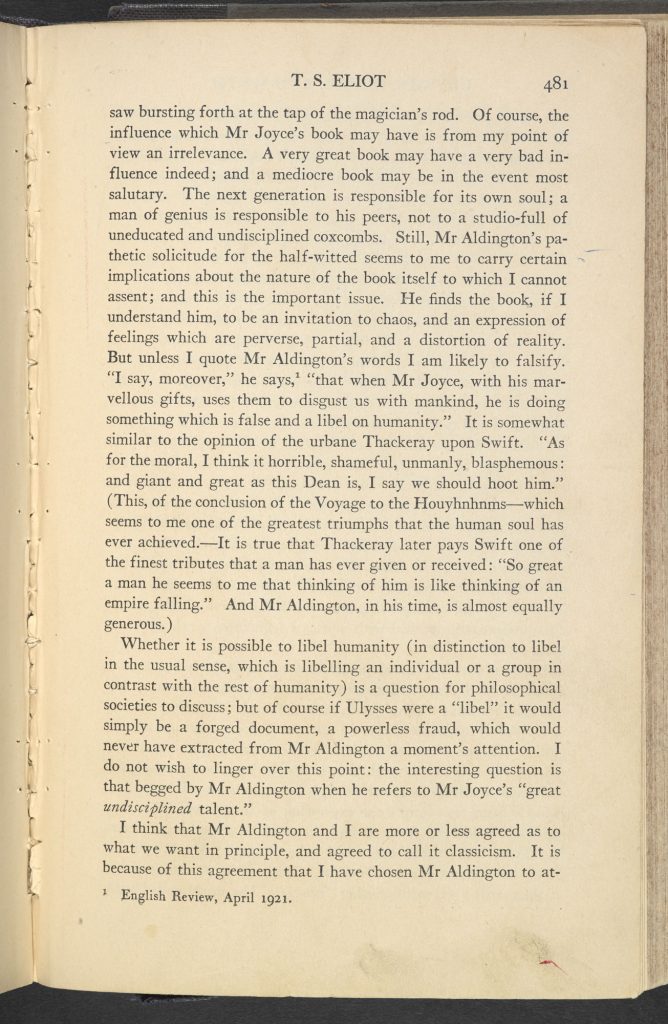

Joyce exerted another influence on Eliot besides Dubliners. As Eliot was thinking about his poem he was reading the instalments of Joyce’s new novel as they appeared: after its publication in book form, Eliot would celebrate Ulysses in a way which spoke to the interests of his own poem very clearly. Joyce’s novel sets incidents in contemporary Dublin against episodes in the Odyssey, running in parallel the story of his Mr Bloom and Ulysses: ‘in manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’, Eliot said,

Mr Joyce is pursuing a method which others must pursue after him. They will not be imitators, any more than the scientist who uses the discoveries of an Einstein in pursuing his own, independent, further investigations. It is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.

Ulysses is in many ways a joyous book, and it is doubtful that Eliot has the tone quite right; but it is very true that his own poem worked by effecting a series of parallels between ancient stories and modern unhappinesses – between Cleopatra and a distracted Londoner, Tiresias and a typist.

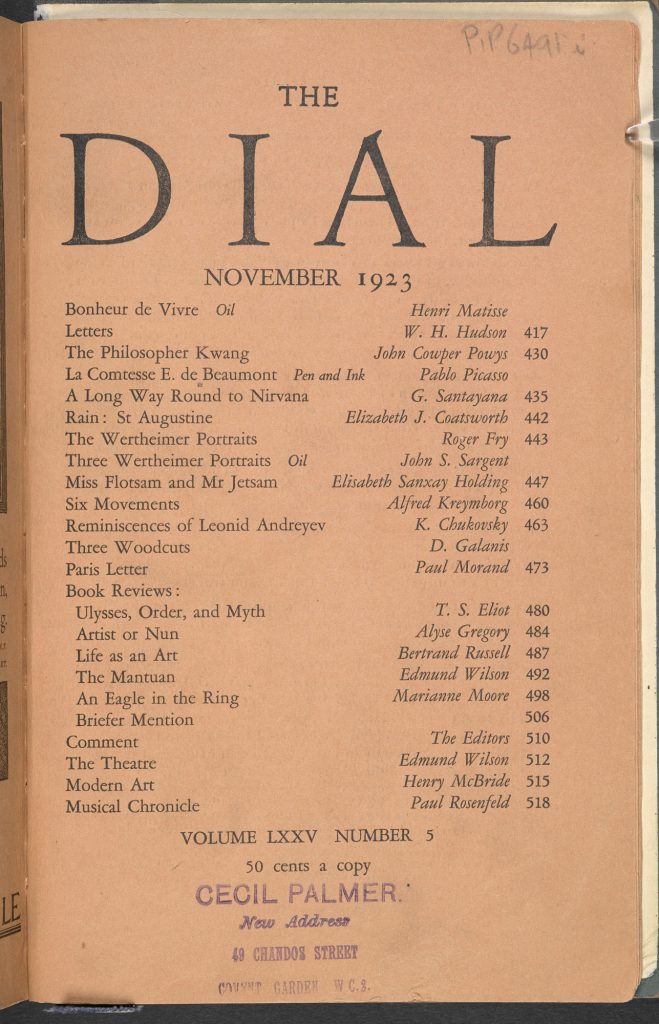

In this November 1923 review of Ulysses, T S Eliot celebrated James Joyce’s use of myth, ‘manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’.

In this November 1923 review of Ulysses, T S Eliot celebrated James Joyce’s use of myth, ‘manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’.

In this November 1923 review of Ulysses, T S Eliot celebrated James Joyce’s use of myth, ‘manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’.

In this November 1923 review of Ulysses, T S Eliot celebrated James Joyce’s use of myth, ‘manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’.

In this November 1923 review of Ulysses, T S Eliot celebrated James Joyce’s use of myth, ‘manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity’.

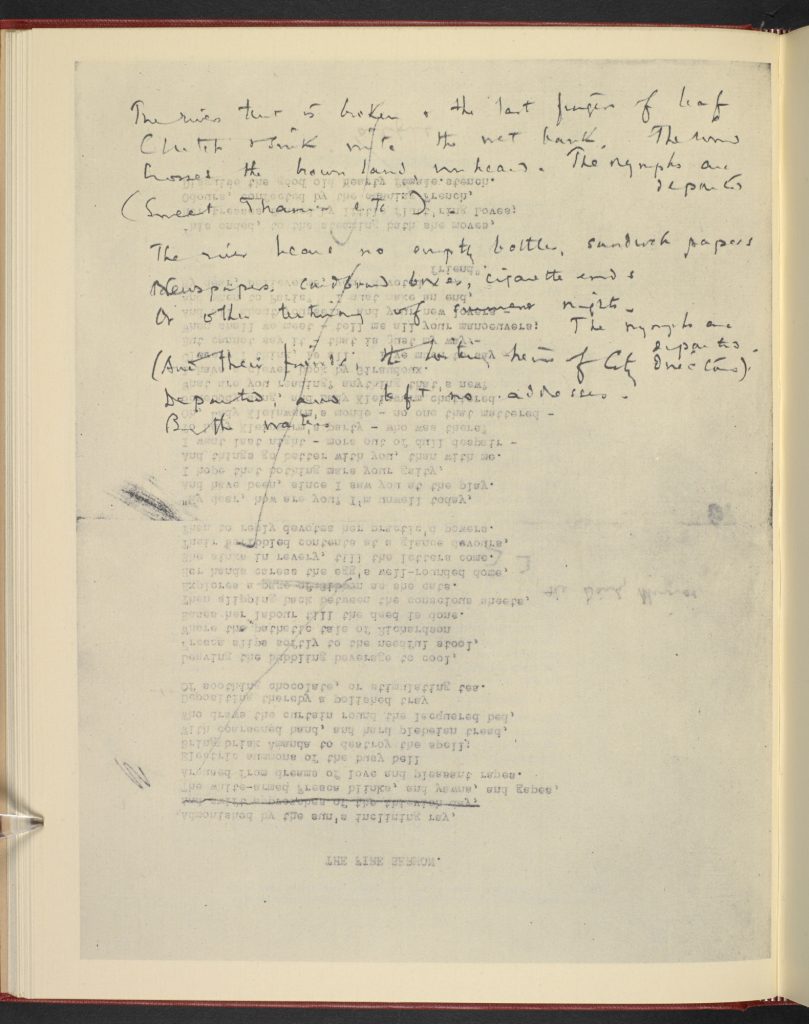

Blake

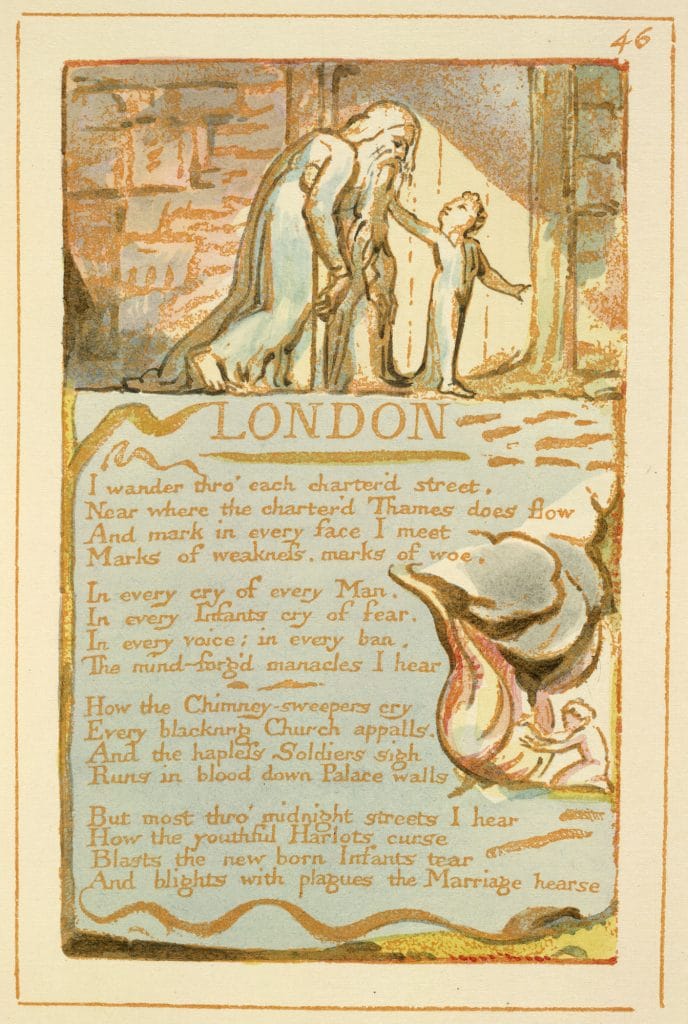

William Blake (1757–1827) is Eliot’s greatest precursor as a poet who cast London as Hell: critics do not often find him in the language of the poem, though Pound for one thought a pair of lines in Eliot’s manuscript too close to him to stand. ‘Blake. Too often used’, he wrote, next to ‘To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the time / With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine’. Eliot changed ‘the time’ to ‘the hours’, presumably to avoid the misrhyme that Pound thought too obviously Blakean: it seems a dubious improvement when hearing ‘a dead sound’ was precisely what was at issue. Generally, though, Blake makes himself felt in The Waste Land – as he doesn’t to any extent in Eliot’s other works – as a spirit, as particularly the poet who wrote:

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

(‘London’, Songs of Experience [1794])

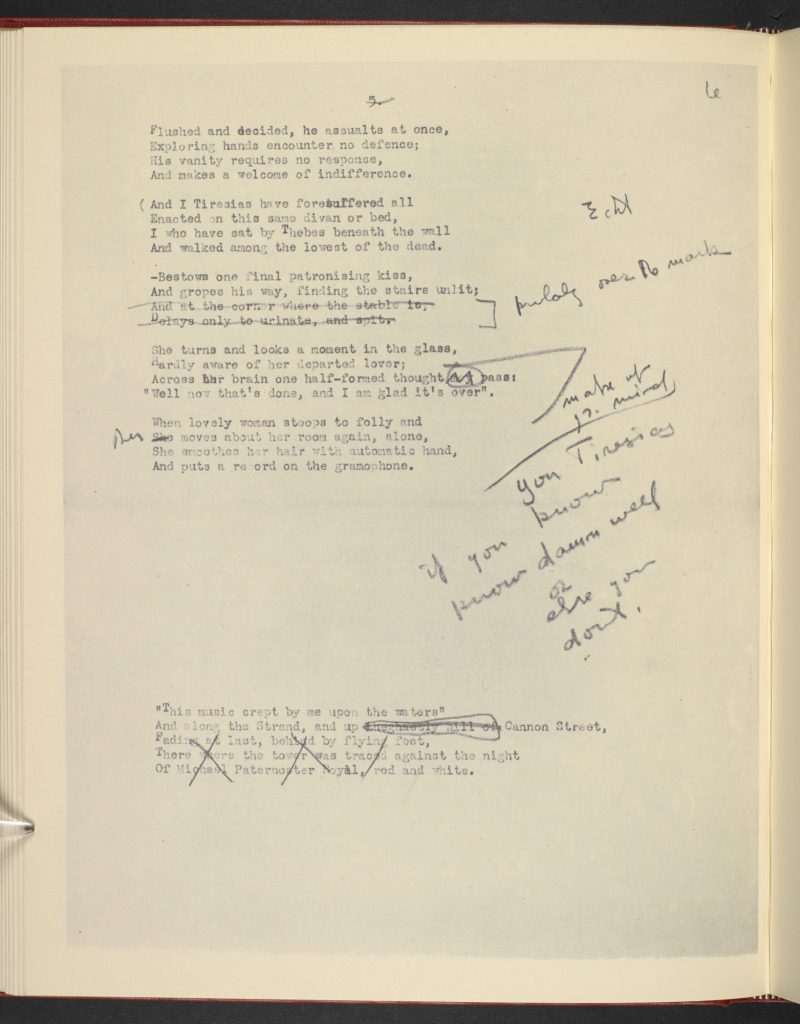

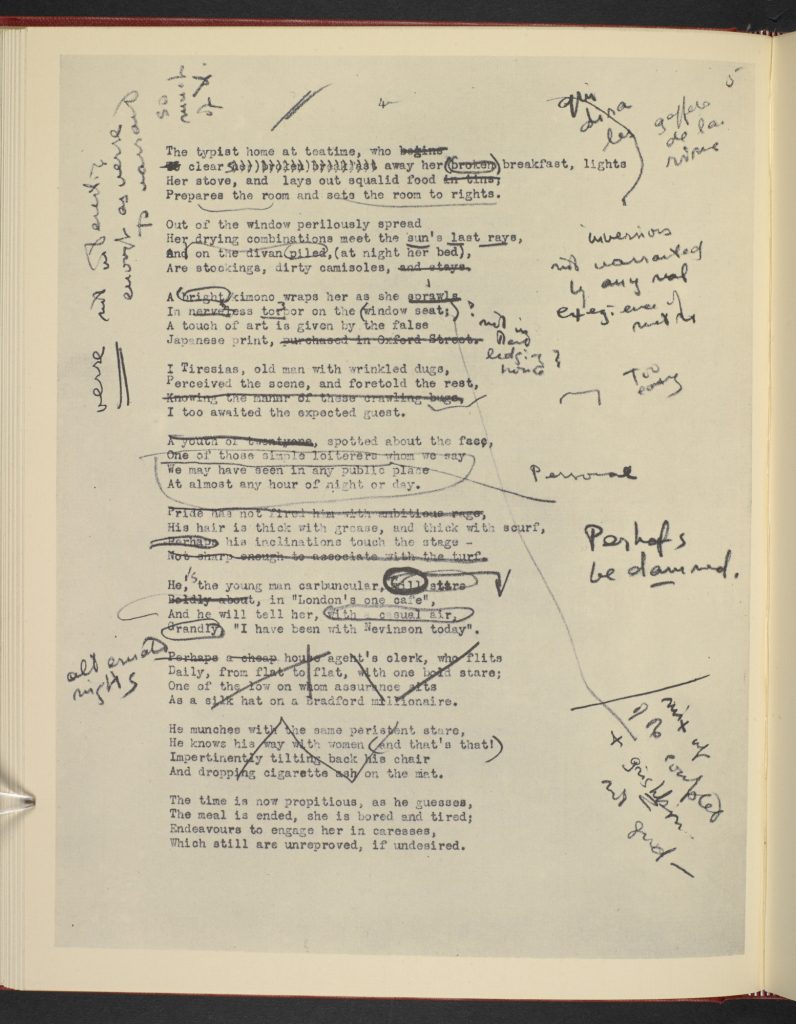

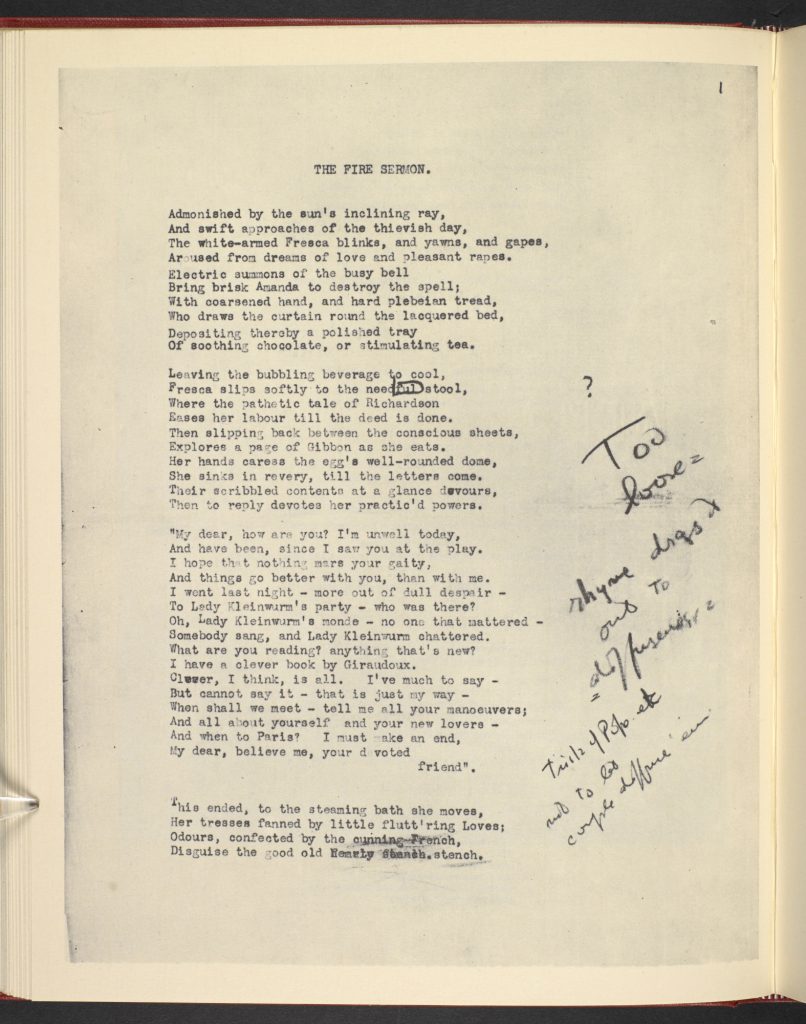

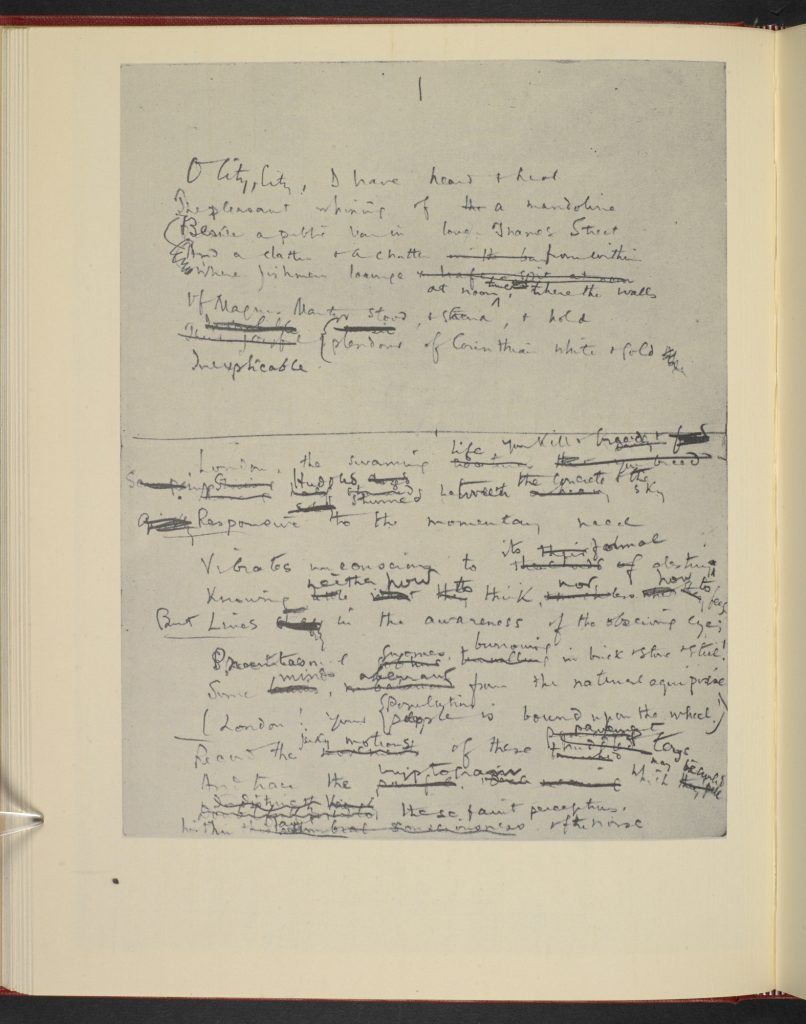

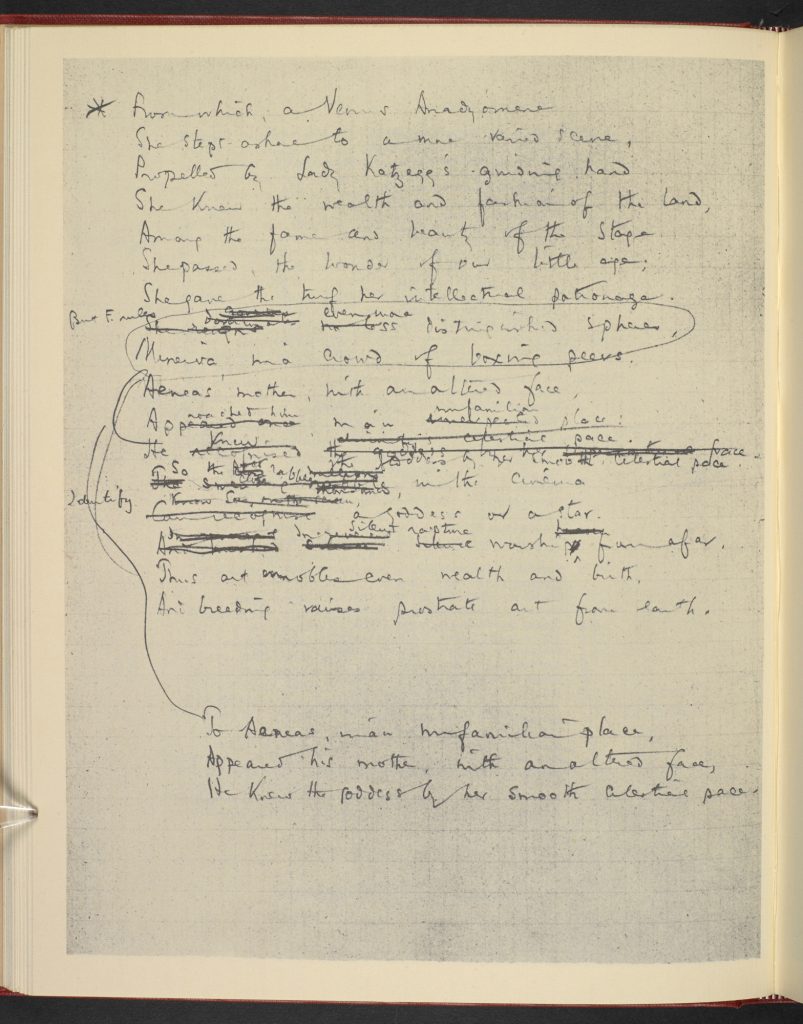

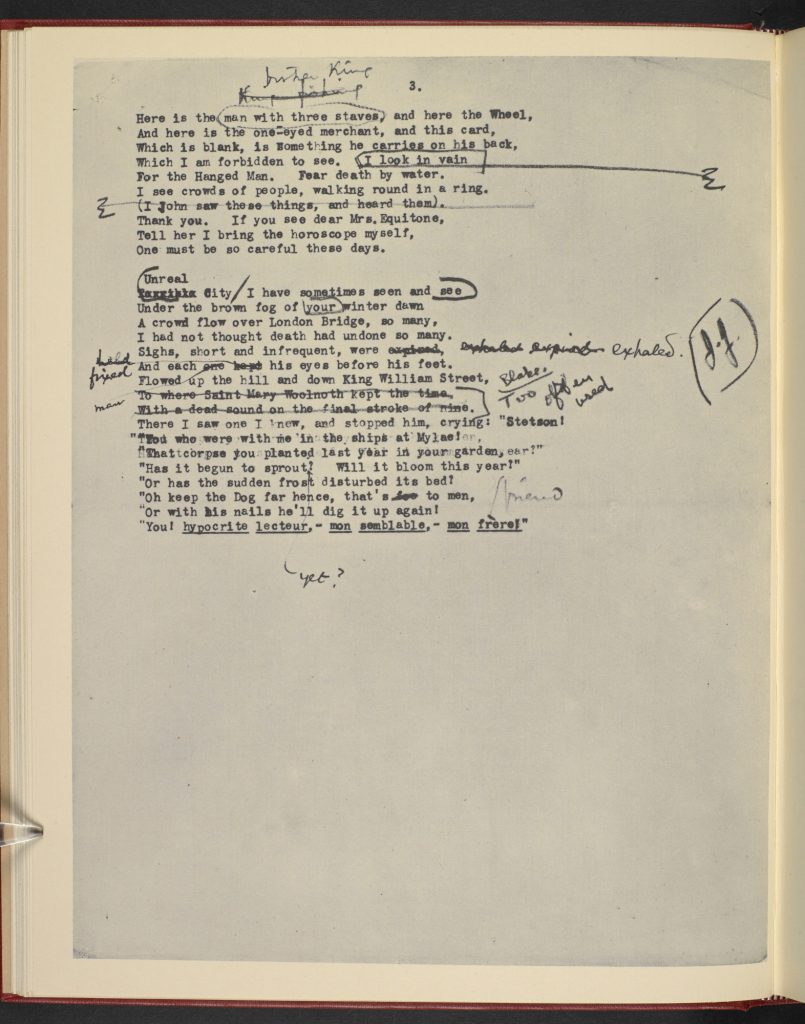

Ezra Pound recommended that T S Eliot amend or delete a pair of lines in The Waste Land that he thought resembled William Blake too closely, commenting ‘Blake. Too often used’ in the manuscript draft.

‘London’ from William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1794.

Eliot admired Blake hugely at this stage in his life, and wrote about him in The Sacred Wood:

Blake’s poetry has the unpleasantness of great poetry. Nothing that can be called morbid or abnormal or perverse, none of the things which exemplify the sickness of an epoch or a fashion, have this quality; only those things which, by some extraordinary labour of simplification, exhibit the essential sickness or strength of the human soul. And this honesty never exists without great technical accomplishment.

Something not dissimilar might be said of The Waste Land, shortly to come together in Eliot’s mind.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Seamus Perry

Seamus Perry is a Fellow of Balliol College and an Associate Professor in the English Faculty, University of Oxford. He is the author of books and articles about, among others, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, T S Eliot, and W H Auden.

相关文章

Sounds in The Waste Land: voices, rhythms, music

The Waste Land is crowded with voices and music, from ancient Hindu and Buddhist scripture to the popular songs of the 1920s. Katherine Mullin listens to the sounds of T S Eliot's poem.