The Romantics

Dr Stephanie Forward explains the key ideas and influences of Romanticism, and considers their place in the work of writers including Wordsworth, Blake, P B Shelley and Keats.

Today the word ‘romantic’ evokes images of love and sentimentality, but the term ‘Romanticism’ has a much wider meaning. It covers a range of developments in art, literature, music and philosophy, spanning the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The ‘Romantics’ would not have used the term themselves: the label was applied retrospectively, from around the middle of the 19th century.

In 1762 Jean-Jacques Rousseau declared in The Social Contract: ‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.’ During the Romantic period major transitions took place in society, as dissatisfied intellectuals and artists challenged the Establishment. In England, the Romantic poets were at the very heart of this movement. They were inspired by a desire for liberty, and they denounced the exploitation of the poor. There was an emphasis on the importance of the individual; a conviction that people should follow ideals rather than imposed conventions and rules. The Romantics renounced the rationalism and order associated with the preceding Enlightenment era, stressing the importance of expressing authentic personal feelings. They had a real sense of responsibility to their fellow men: they felt it was their duty to use their poetry to inform and inspire others, and to change society.

Revolution

When reference is made to Romantic verse, the poets who generally spring to mind are William Blake (1757-1827), William Wordsworth (1770-1850), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), George Gordon, 6th Lord Byron (1788-1824), Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) and John Keats (1795-1821). These writers had an intuitive feeling that they were ‘chosen’ to guide others through the tempestuous period of change.

This was a time of physical confrontation; of violent rebellion in parts of Europe and the New World. Conscious of anarchy across the English Channel, the British government feared similar outbreaks. The early Romantic poets tended to be supporters of the French Revolution, hoping that it would bring about political change; however, the bloody Reign of Terror shocked them profoundly and affected their views. In his youth William Wordsworth was drawn to the Republican cause in France, until he gradually became disenchanted with the Revolutionaries.

The imagination

The Romantics were not in agreement about everything they said and did: far from it! Nevertheless, certain key ideas dominated their writings. They genuinely thought that they were prophetic figures who could interpret reality. The Romantics highlighted the healing power of the imagination, because they truly believed that it could enable people to transcend their troubles and their circumstances. Their creative talents could illuminate and transform the world into a coherent vision, to regenerate mankind spiritually. In A Defence of Poetry (1821), Shelley elevated the status of poets: ‘They measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature with a comprehensive and all-penetrating spirit…’.[1] He declared that ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’. This might sound somewhat pretentious, but it serves to convey the faith the Romantics had in their poetry.

The marginalised and oppressed

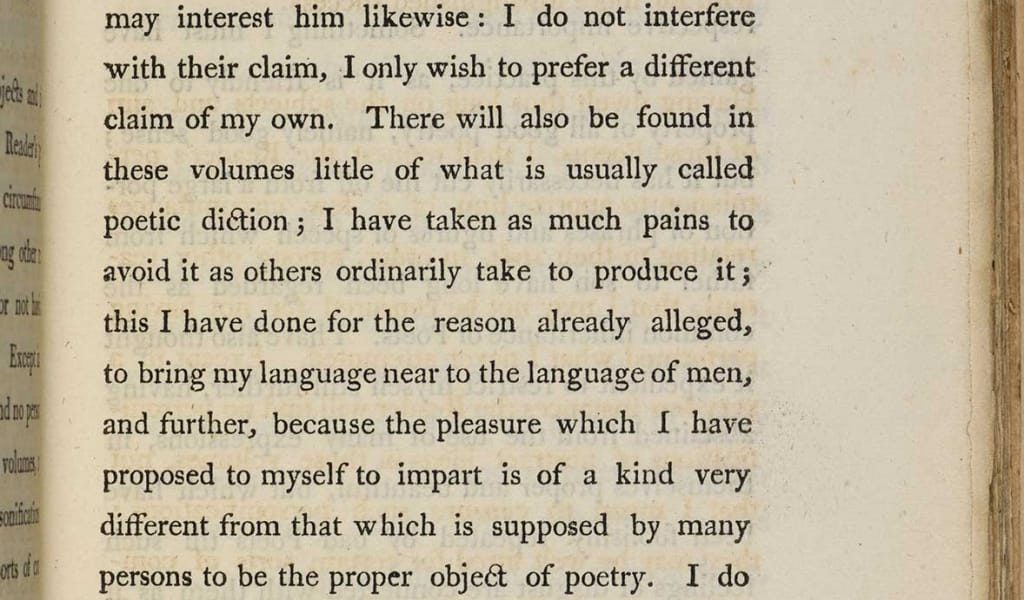

Wordsworth was concerned about the elitism of earlier poets, whose highbrow language and subject matter were neither readily accessible nor particularly relevant to ordinary people. He maintained that poetry should be democratic; that it should be composed in ‘the language really spoken by men’ (Preface to Lyrical Ballads [1802]). For this reason, he tried to give a voice to those who tended to be marginalised and oppressed by society: the rural poor; discharged soldiers; ‘fallen’ women; the insane; and children.

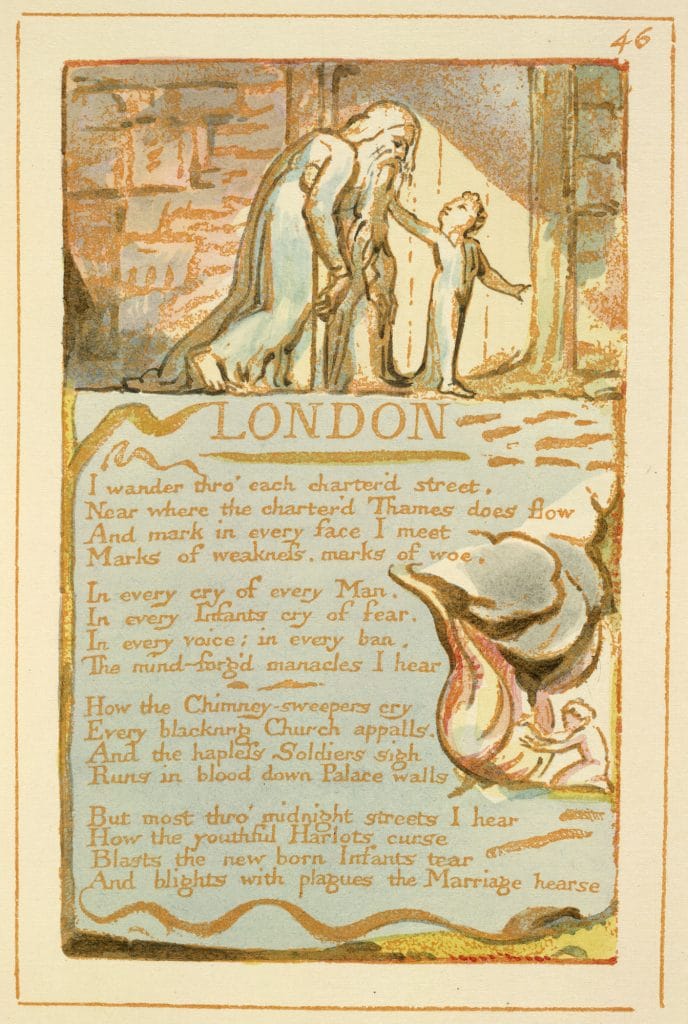

Blake was radical in his political views, frequently addressing social issues in his poems and expressing his concerns about the monarchy and the church. His poem ‘London’ draws attention to the suffering of chimney-sweeps, soldiers and prostitutes.

Children, nature and the sublime

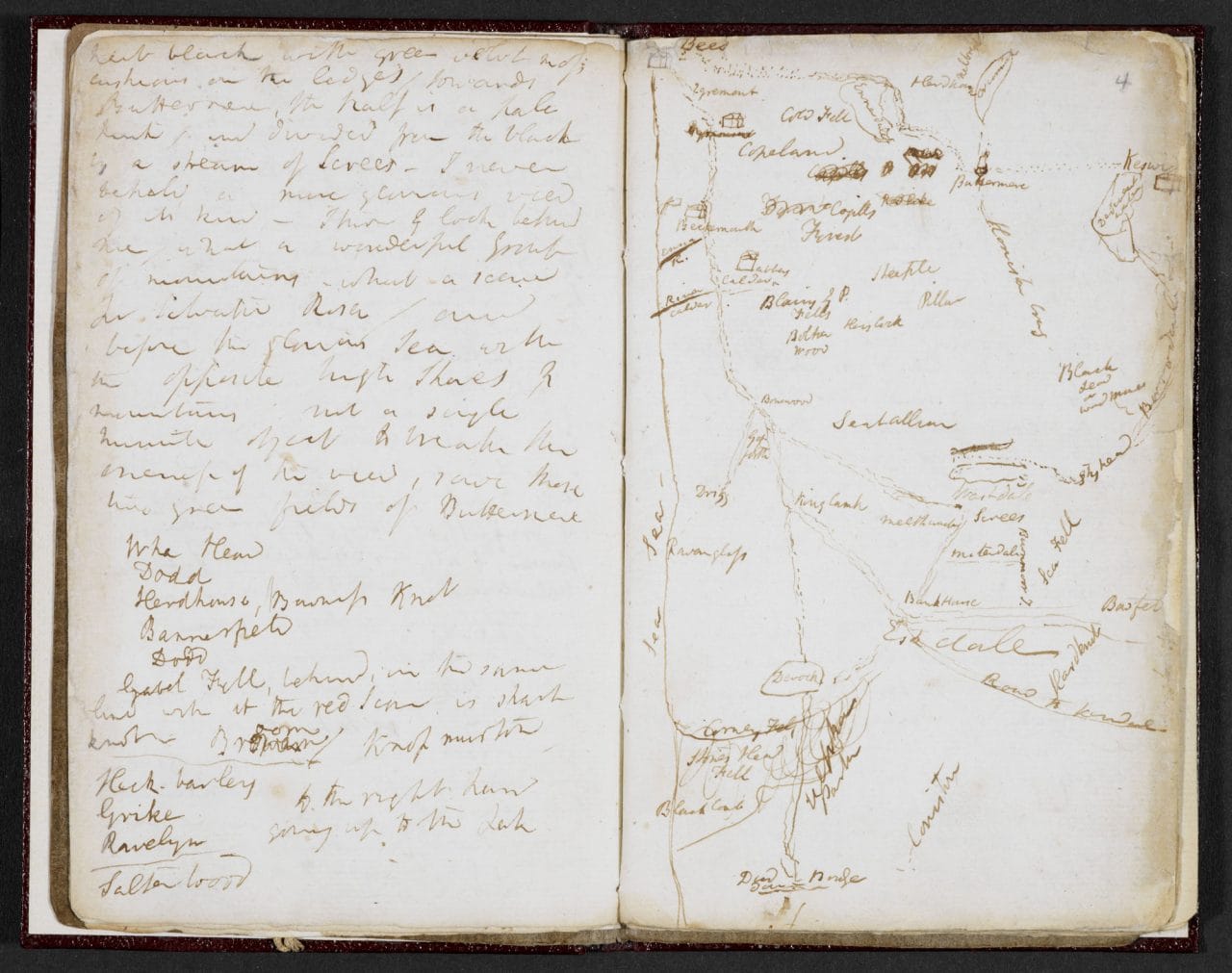

For the world to be regenerated, the Romantics said that it was necessary to start all over again with a childlike perspective. They believed that children were special because they were innocent and uncorrupted, enjoying a precious affinity with nature. Romantic verse was suffused with reverence for the natural world. In Coleridge’s ‘Frost at Midnight’ (1798) the poet hailed nature as the ‘Great universal Teacher!’ Recalling his unhappy times at Christ’s Hospital School in London, he explained his aspirations for his son, Hartley, who would have the freedom to enjoy his childhood and appreciate his surroundings. The Romantics were inspired by the environment, and encouraged people to venture into new territories – both literally and metaphorically. In their writings they made the world seem a place with infinite, unlimited potential.

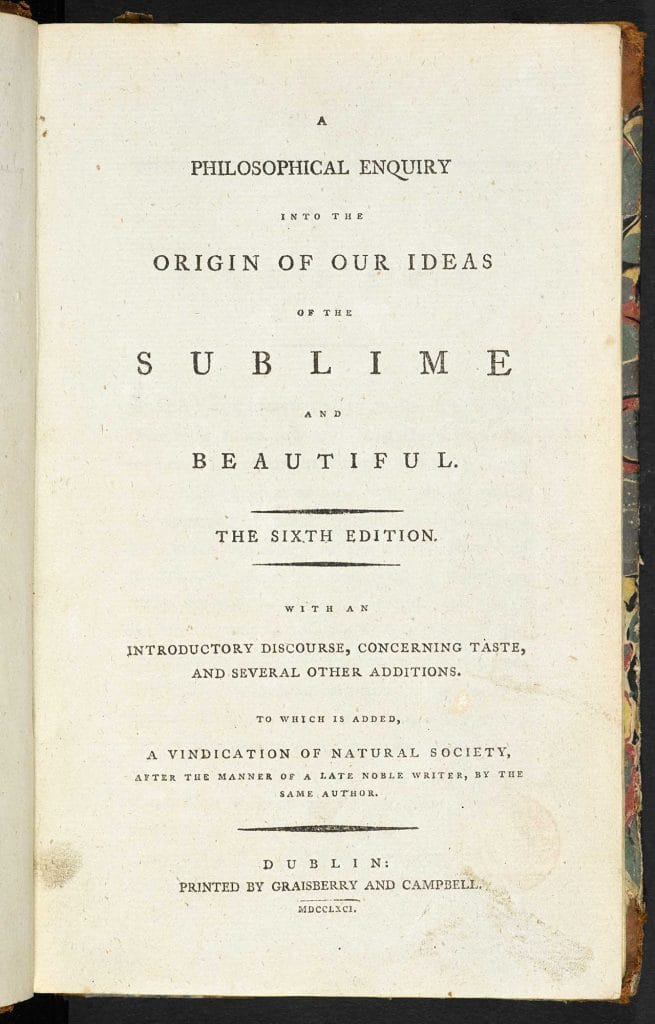

A key idea in Romantic poetry is the concept of the sublime. This term conveys the feelings people experience when they see awesome landscapes, or find themselves in extreme situations which elicit both fear and admiration. For example, Shelley described his reaction to stunning, overwhelming scenery in the poem ‘Mont Blanc’ (1816).

The second-generation Romantics

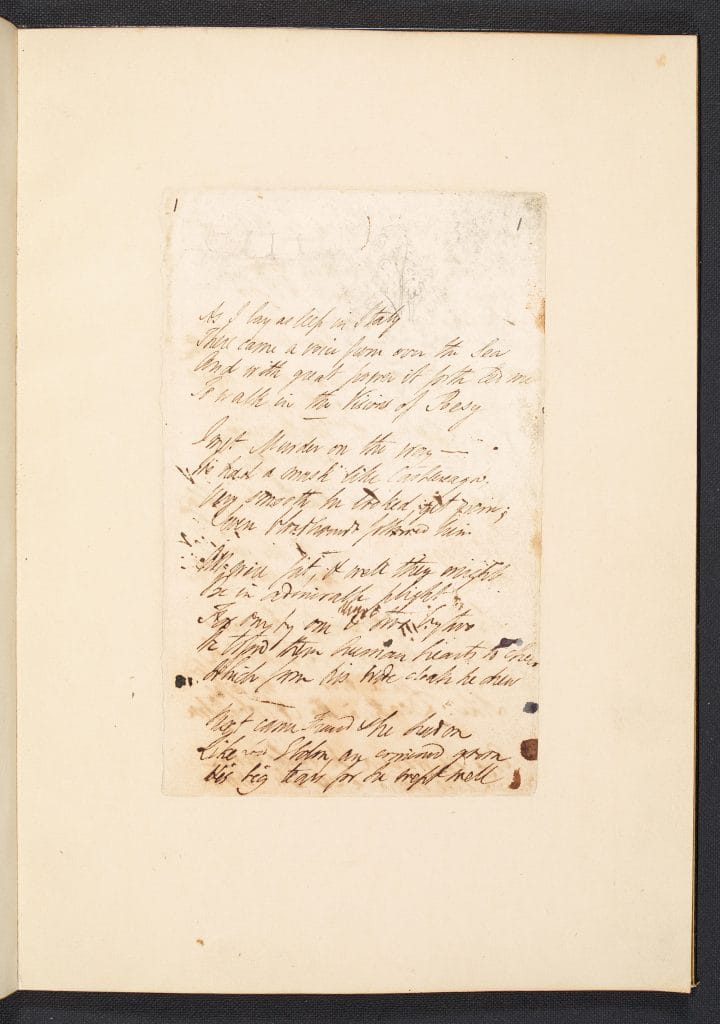

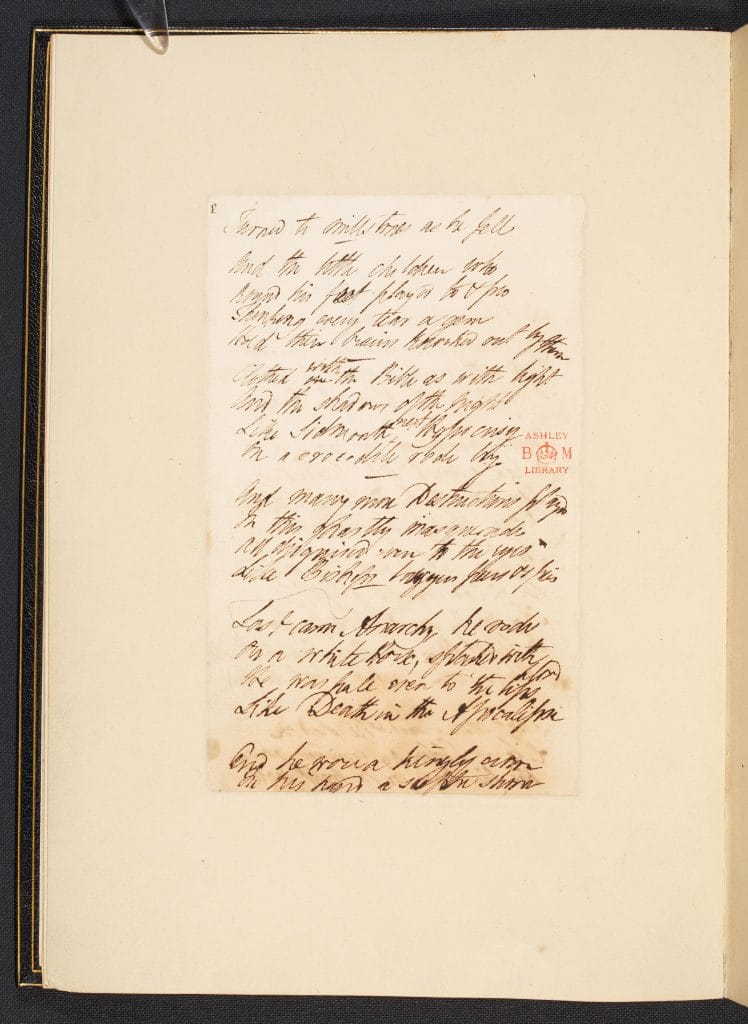

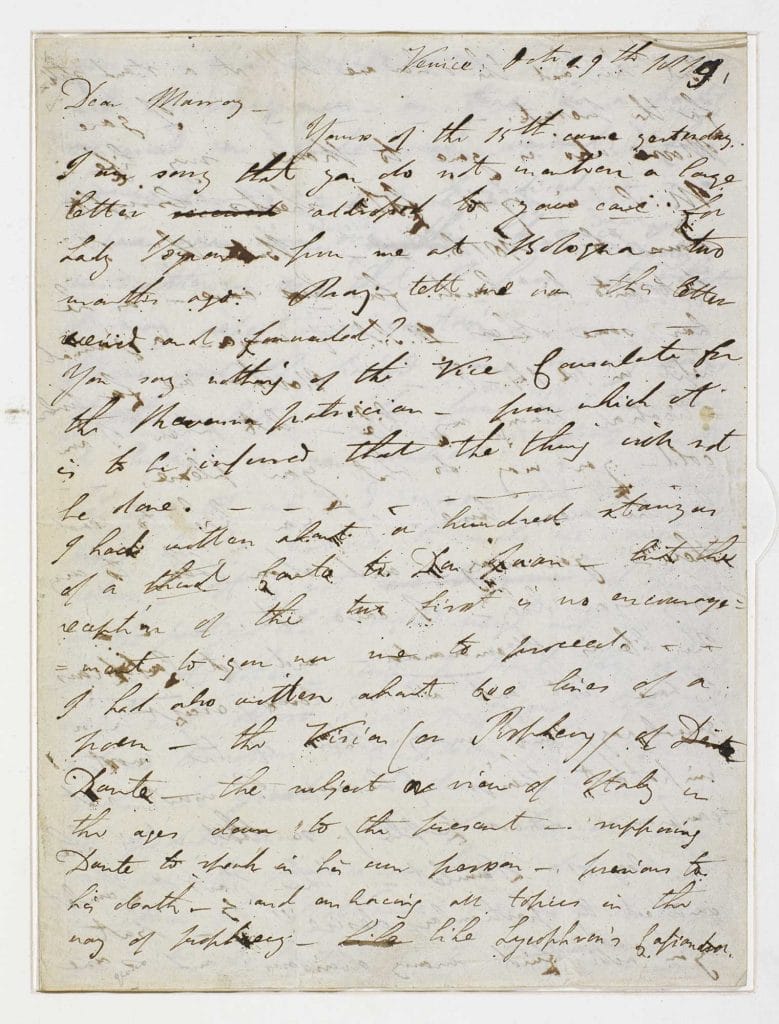

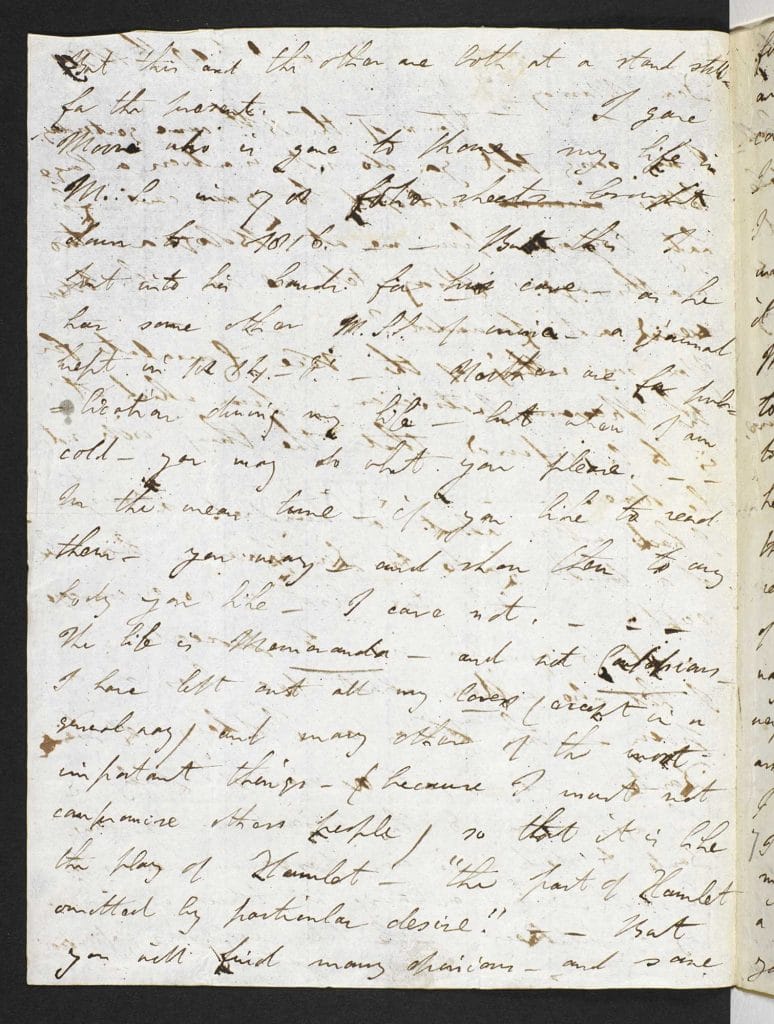

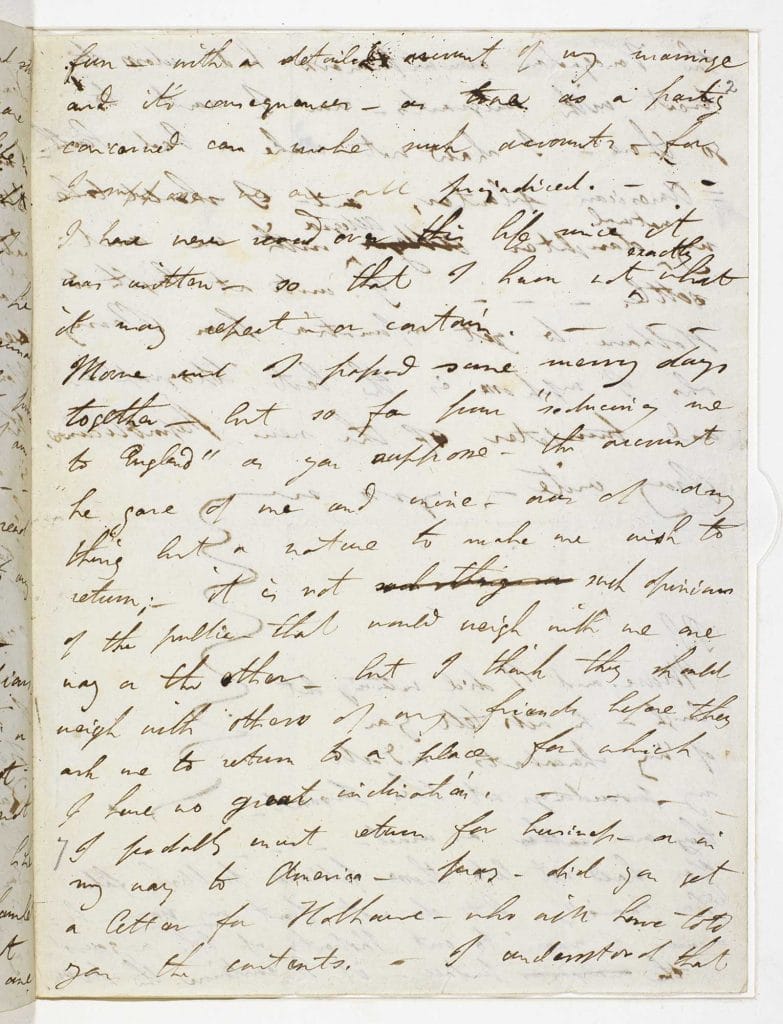

Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge were first-generation Romantics, writing against a backdrop of war. Wordsworth, however, became increasingly conservative in his outlook: indeed, second-generation Romantics, such as Byron, Shelley and Keats, felt that he had ‘sold out’ to the Establishment. In the suppressed Dedication to Don Juan (1819-1824) Byron criticised the Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, and the other ‘Lakers’, Wordsworth and Coleridge (all three lived in the Lake District). Byron also vented his spleen on the English Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, denouncing him as an ‘intellectual eunuch’, a ‘bungler’ and a ‘tinkering slavemaker’ (stanzas 11 and 14). Although the Romantics stressed the importance of the individual, they also advocated a commitment to mankind. Byron became actively involved in the struggles for Italian nationalism and the liberation of Greece from Ottoman rule. Notorious for his sexual exploits, and dogged by debt and scandal, Byron quitted Britain in 1816. Lady Caroline Lamb famously declared that he was ‘Mad, bad and dangerous to know.’ Similar accusations were pointed at Shelley. Nicknamed ‘Mad Shelley’ at Eton, he was sent down from Oxford for advocating atheism. He antagonised the Establishment further by his criticism of the monarchy, and by his immoral lifestyle.

Female poets

Female poets also contributed to the Romantic movement, but their strategies tended to be more subtle and less controversial. Although Dorothy Wordsworth (1771-1855) was modest about her writing abilities, she produced poems of her own; and her journals and travel narratives certainly provided inspiration for her brother. Women were generally limited in their prospects, and many found themselves confined to the domestic sphere; nevertheless, they did manage to express or intimate their concerns. For example, Mary Alcock (c. 1742-1798) penned ‘The Chimney Sweeper’s Complaint’. In ‘The Birth-Day’, Mary Robinson (1758-1800) highlighted the enormous discrepancy between life for the rich and the poor. Gender issues were foregrounded in ‘Indian Woman’s Death Song’ by Felicia Hemans (1793-1835).

The Gothic

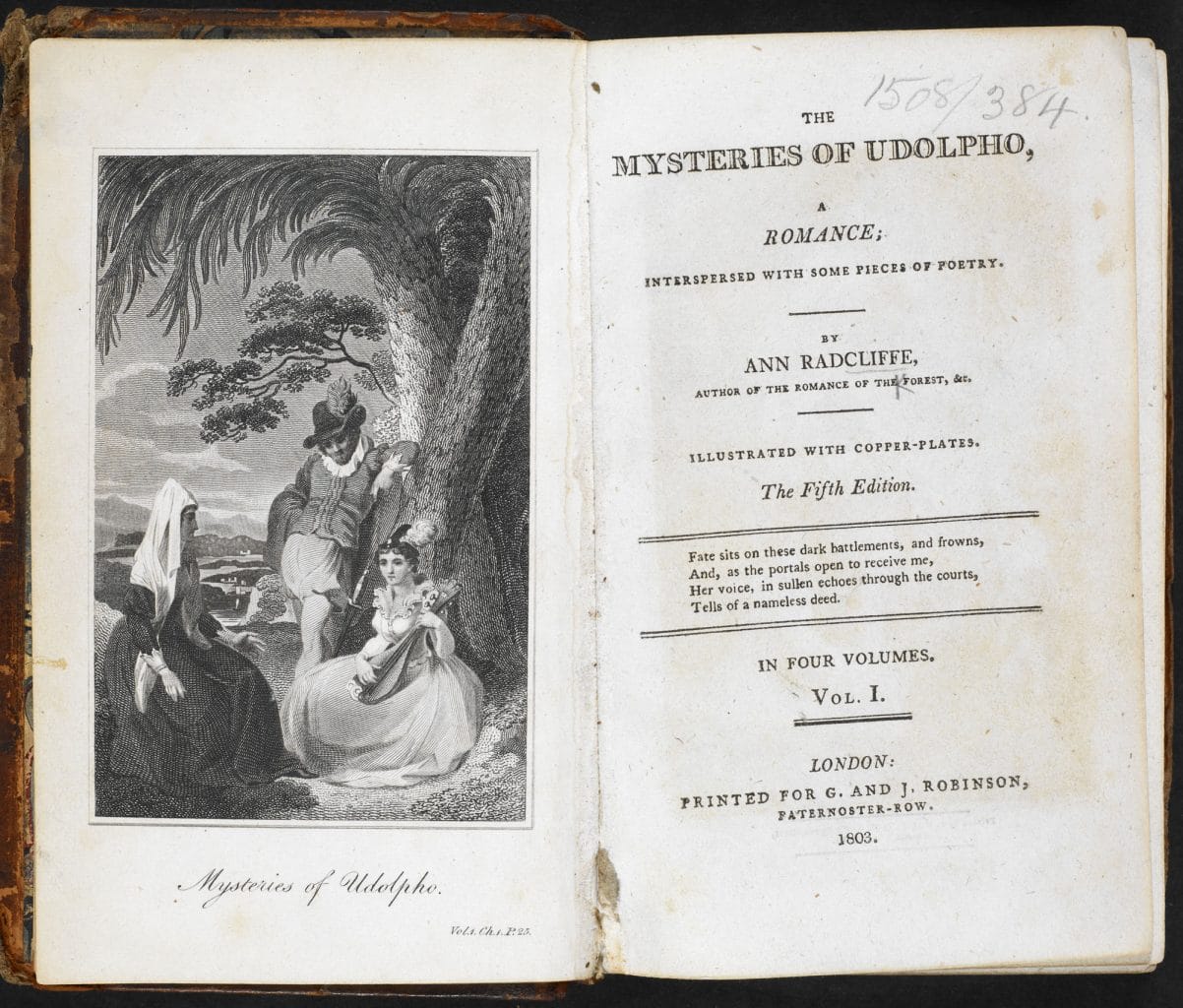

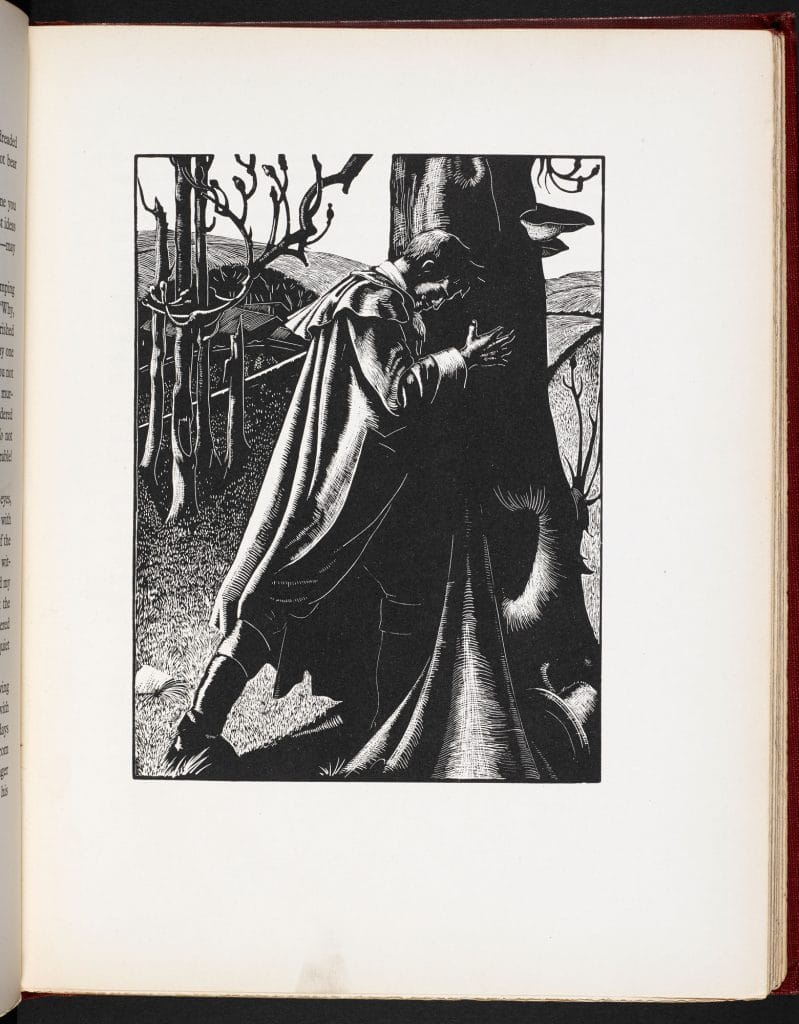

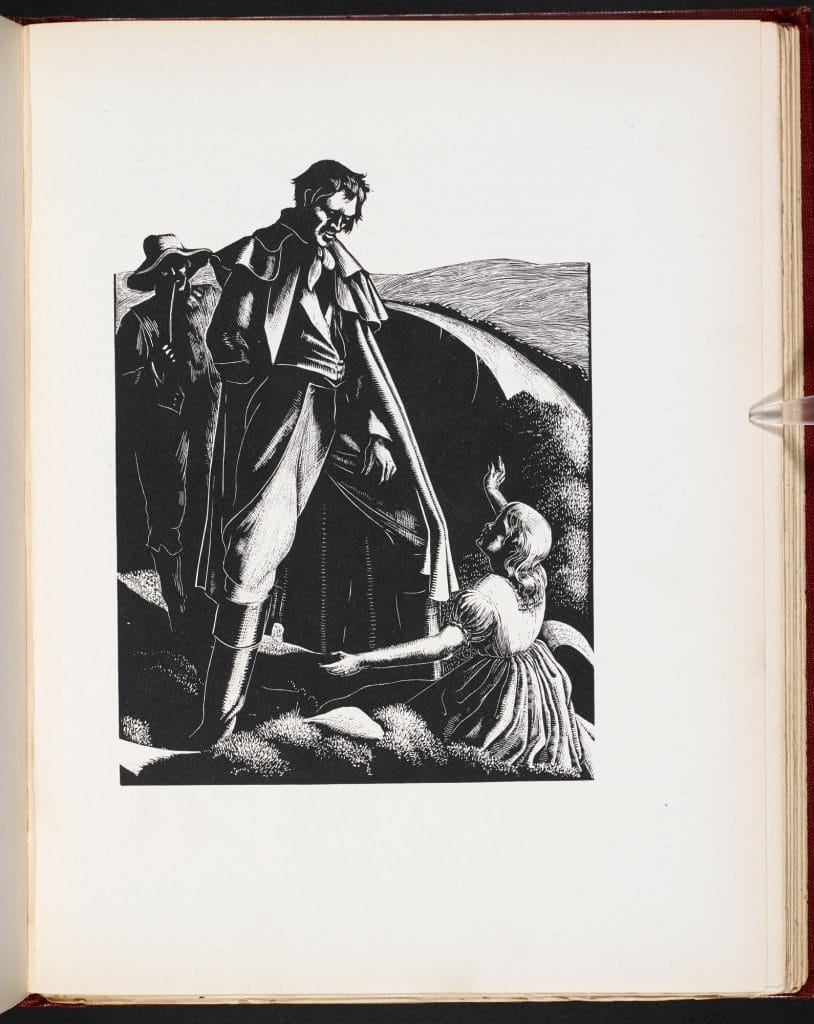

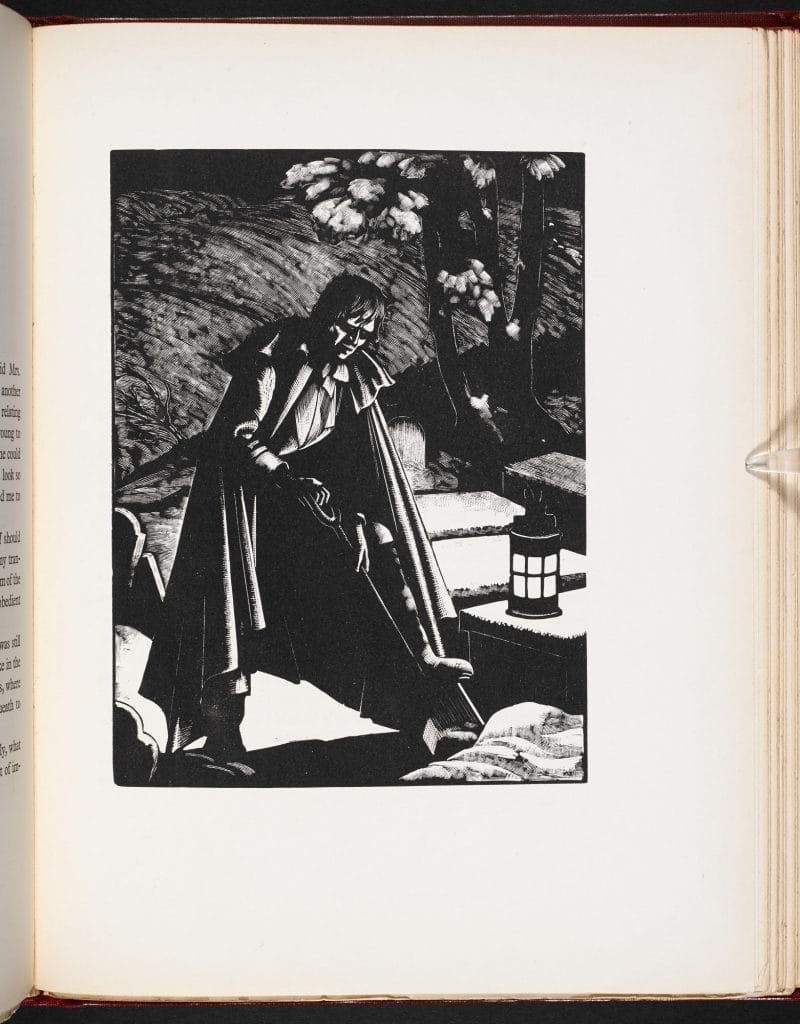

Reaction against the Enlightenment was reflected in the rise of the Gothic novel. The most popular and well-paid 18th-century novelist, Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823), specialised in ‘the hobgoblin-romance’. Her fiction held particular appeal for frustrated middle-class women who experienced a vicarious frisson of excitement when they read about heroines venturing into awe-inspiring landscapes. She was dubbed ‘Mother Radcliffe’ by Keats, because she had such an influence on Romantic poets. The Gothic genre contributed to Coleridge’s Christabel (1816) and Keats’s ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ (1819). Mary Shelley (1797-1851) blended realist, Gothic and Romantic elements to produce her masterpiece Frankenstein (1818), in which a number of Romantic aspects can be identified. She quotes from Coleridge’s Romantic poem The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere. In the third chapter Frankenstein refers to his scientific endeavours being driven by his imagination. The book raises worrying questions about the possibility of ‘regenerating’ mankind; but at several points the world of nature provides inspiration and solace.

The Byronic hero

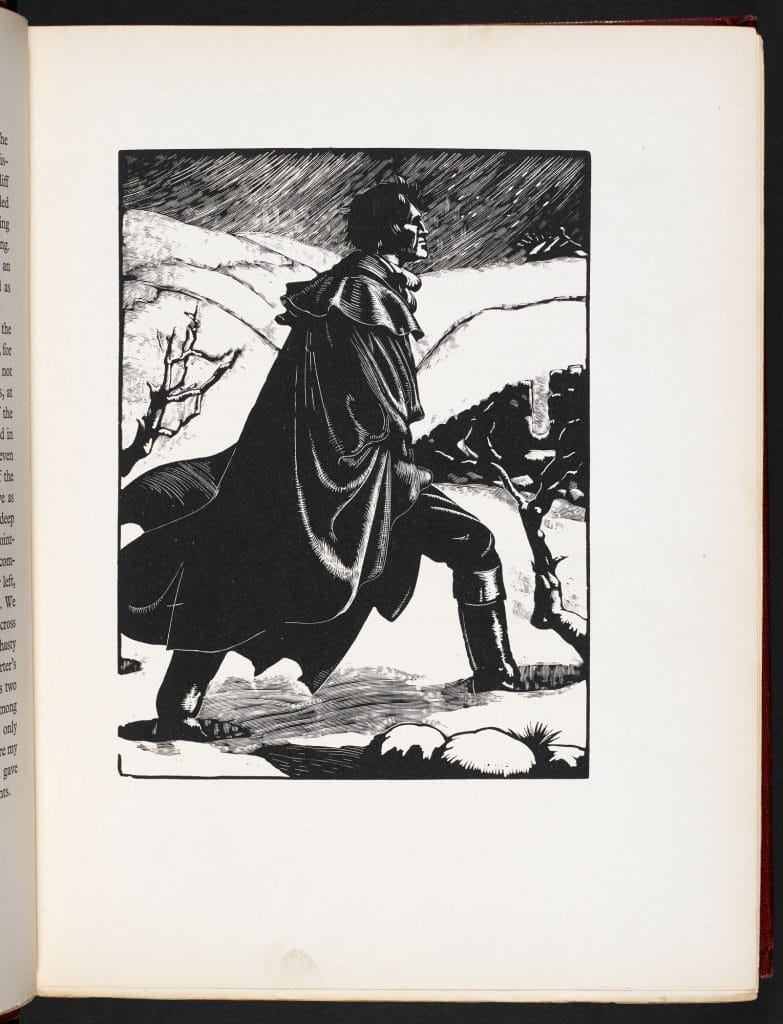

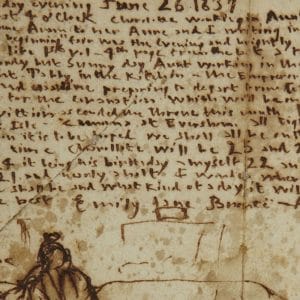

Romanticism set a trend for some literary stereotypes. Byron’s Childe Harold (1812-1818) described the wanderings of a young man, disillusioned with his empty way of life. The melancholy, dark, brooding, rebellious ‘Byronic hero’, a solitary wanderer, seemed to represent a generation, and the image lingered. The figure became a kind of role model for youngsters: men regarded him as ‘cool’ and women found him enticing! Byron died young, in 1824, after contracting a fever. This added to the ‘appeal’. Subsequently a number of complex and intriguing heroes appeared in novels: for example, Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Edward Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (both published in 1847).

Contraries

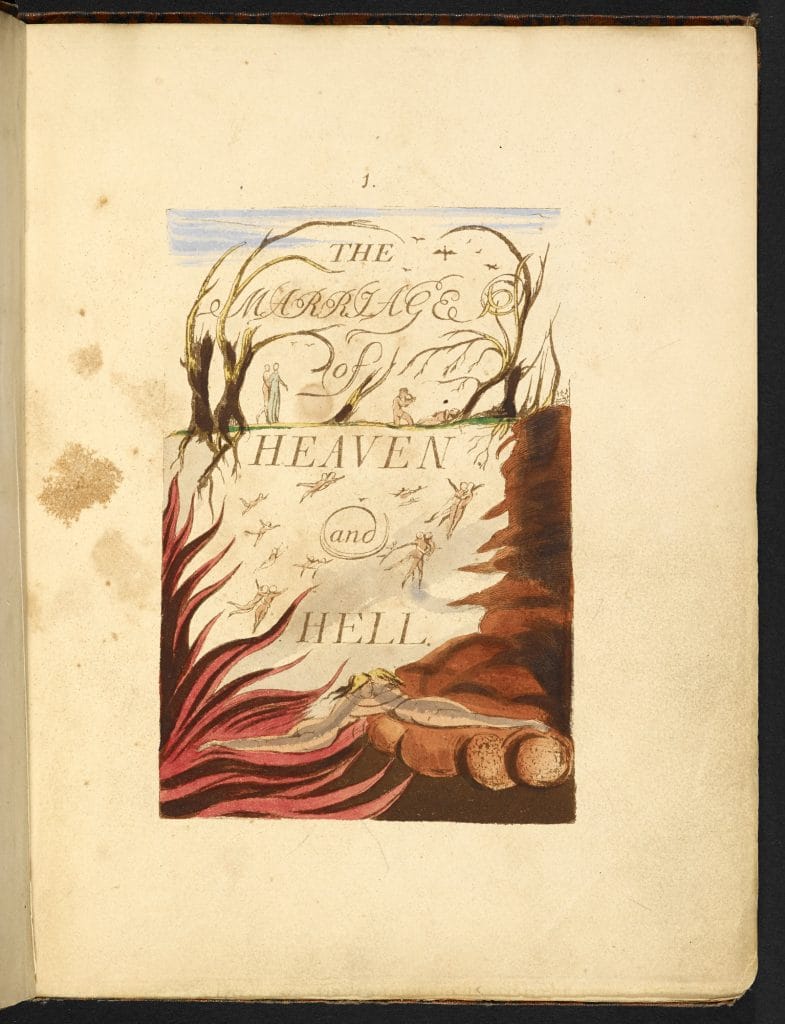

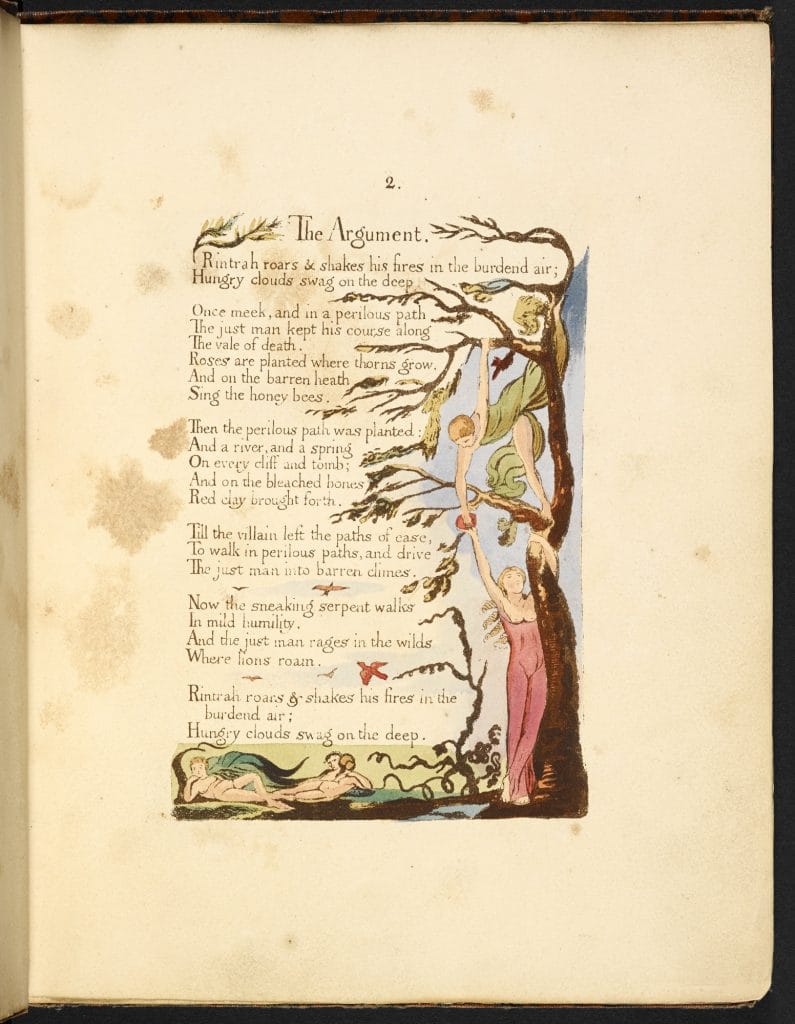

Romanticism offered a new way of looking at the world, prioritising imagination above reason. There was, however, a tension at times in the writings, as the poets tried to face up to life’s seeming contradictions. Blake published Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul (1794). Here we find two different perspectives on religion in ‘The Lamb’ and ‘The Tyger’. The simple vocabulary and form of ‘The Lamb’ suggest that God is the beneficent, loving Good Shepherd. In stark contrast, the creator depicted in ‘The Tyger’ is a powerful blacksmith figure. The speaker is stunned by the exotic, frightening animal, posing the rhetorical question: ‘Did he who made the Lamb make thee?’ In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-1793) Blake asserted: ‘Without contraries is no progression’ (stanza 8).

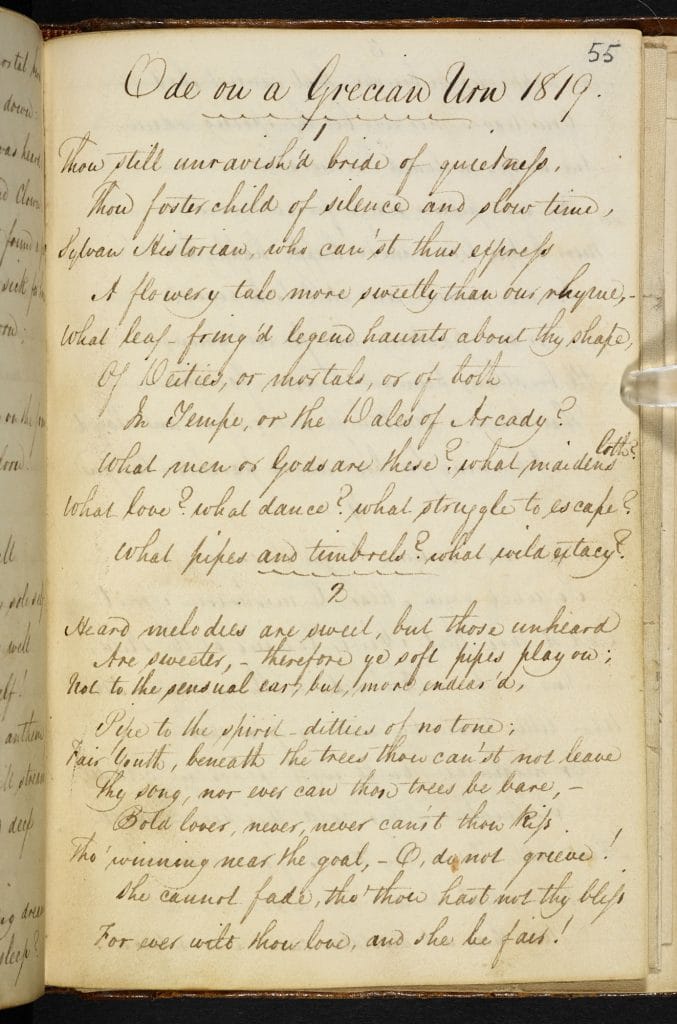

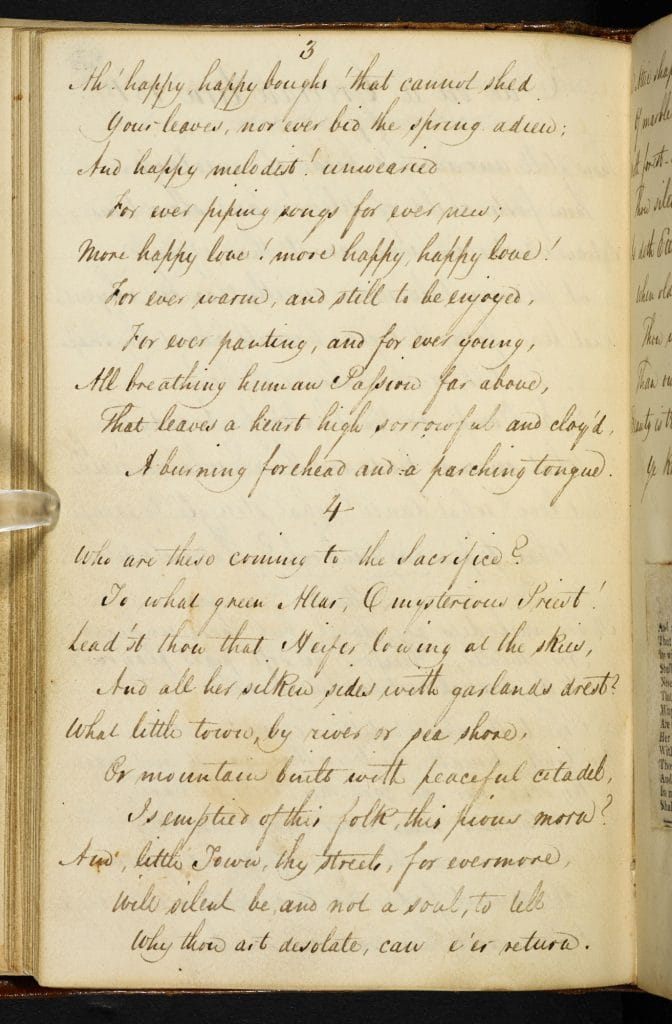

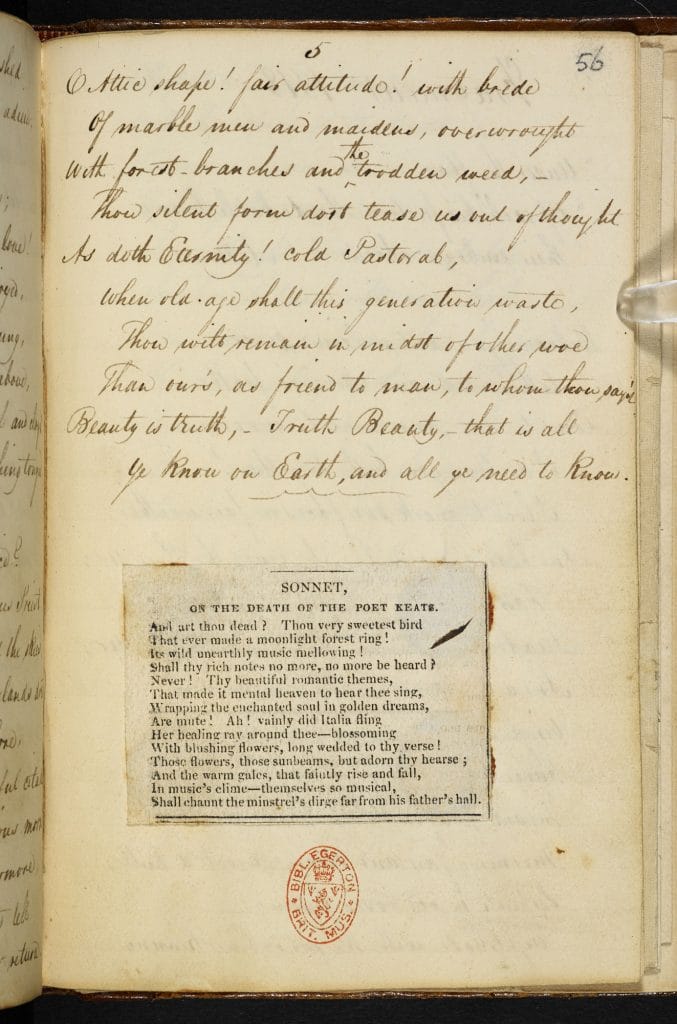

Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ (1798) juxtaposed moments of celebration and optimism with lamentation and regret. Keats thought in terms of an opposition between the imagination and the intellect. In a letter to his brothers, in December 1817, he explained what he meant by the term ‘Negative Capability’: ‘that is when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’ (22 December). Keats suggested that it is impossible for us to find answers to the eternal questions we all have about human existence. Instead, our feelings and imaginations enable us to recognise Beauty, and it is Beauty that helps us through life’s bleak moments. Life involves a delicate balance between times of pleasure and pain. The individual has to learn to accept both aspects: ‘“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” – that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know’ (‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ [1819]).

The premature deaths of Byron, Shelley and Keats contributed to their mystique. As time passed they attained iconic status, inspiring others to make their voices heard. The Romantic poets continue to exert a powerful influence on popular culture. Generations have been inspired by their promotion of self-expression, emotional intensity, personal freedom and social concern.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Stephanie Forward

Dr Stephanie Forward is a lecturer, specializing in English Literature. She has been involved in two important collaborative projects between the Open University and the BBC: The Big Read, and the television series The Romantics, and was a contributor to the British Library’s Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians site and to the 20th century site. Stephanie has an extensive publications record. She also edited the anthology Dreams, Visions and Realities; co-edited (with Ann Heilmann) Sex, Social Purity and Sarah Grand, and penned the script for the C.D. Blenheim Palace: The Churchills and their Palace.