Lord Byron, 19th-century bad boy

Clara Drummond explains how Lord Byron’s politics, relationships and views on other poets led to his reputation of 19th-century bad boy.

The great object of life is Sensation – to feel that we exist – even though in pain – it is this ‘craving void’ which drives us to Gaming – to Battle – to Travel – to intemperate but keenly felt pursuits of every description whose principle attraction is the agitation inseparable from their accomplishment. (Lord Byron to Annabella Milbanke, his future wife, 6 September, 1813)

Born in London in 1788, the poet George Gordon Byron, or Lord Byron as we know him, spent his life collecting sensations and courting controversy. While a student at Cambridge, for example, he kept a tame bear as a pet, taking it for walks as one would a dog. During his acrimonious and very public divorce in 1816, Byron was rumoured to be having a sexual relationship with his half-sister, an allegation he denied in public but less adamantly in his private letters. His passionate support for the freedom of the Greeks in their War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire was likewise a ‘keenly felt pursuit’ that ultimately proved deadly. Suffering from a fever and infection contracted while awaiting battle in Greece, Byron died in 1824 at the age of 36.

Although in his letters Byron confessed to having no interest in society – ‘I only go out to get me a fresh appetite for being alone,’ – his exploits and writings drew attention, at times adoring and at others deeply critical. It was in 1812 after the publication of the first part of his long narrative poem about a young aristocrat’s travels, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, that Byron became widely known, a celebrity in fashionable circles. With a noticeable limp due to a club-foot – a disability he had suffered with from birth – and a striking face, Byron’s physical presence also commanded attention. His fellow English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge commented in a letter on 10 April 1816 that Byron’s face was ‘so beautiful, a countenance I scarcely ever saw’ and ‘his eyes the open portals of the sun—things of light, and for light’. During his lifetime, Byron was notoriously protective of his image and directed his publisher John Murray to destroy any engravings of himself that he disliked. One portrait he endorsed was completed in 1813 by the artist Thomas Phillips.

It shows Byron wearing Albanian dress, ‘the most magnificent in the world’, Byron thought, which he had acquired while on a Grand Tour of the Mediterranean in 1809. The portrait alludes to his travels and adventurous spirit while presenting the face of a calm and pensive Byron. Known to be moody, by turns gregarious and then sullen, Byron was a man of extremes, both in terms of his character and his deeds. In a candid moment of self-reflection Byron wrote, ‘I am so changeable, being everything by turns and nothing long, – I am such a strange mélange of good and evil, that it would be difficult to describe me’.[1]

Politics

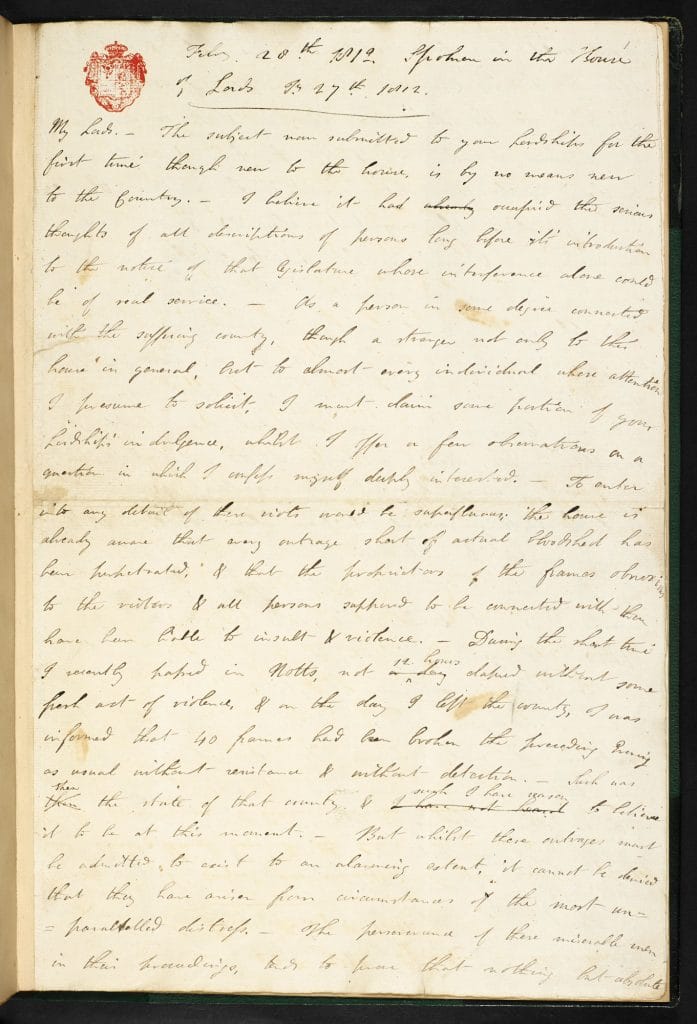

From a young age, Byron wished for a career in Parliament with poetry initially being only a secondary interest. He entered the House of Lords, his privilege for being born into British nobility, and in 1812 gave his first speech opposing the Frame Work Bill, which made the destruction of stocking frames, mechanical looms used in the textile industry, a crime punishable by death.

The controversy over the bill had provoked riots in Nottinghamshire where use of the frames had left many men unemployed, and therefore hungry and desperate. In the historic speech, Byron laments that many of his fellow politicians view the rioters as an uneducated mob, failing to recognise the desperation of their situation:

it is the mob that labour in your fields and in your houses – that man your navy and recruit your army – that have enabled you to defy all the world and can also defy you when neglect and calamity have driven them to despair .You may call the people a mob but not forget that a mob too often speaks the sentiments of the people.[2]

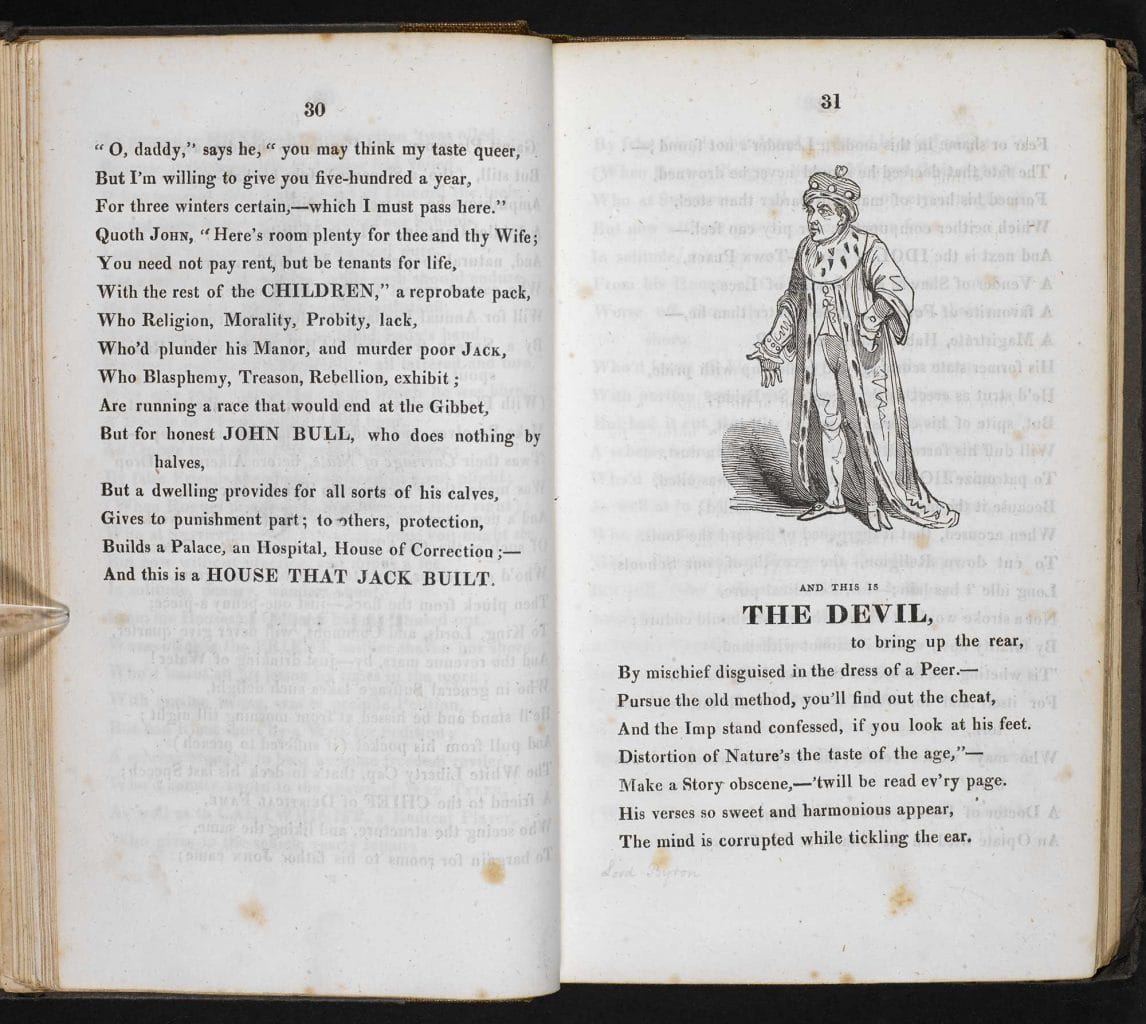

Despite the eloquence and passion of Byron’s speech opposing the bill, the bill passed. Seen as a radical, Byron became the enemy of the more conservative forces as made clear by his representation as the devil with a cloven hoof in The Dorchester Guide; or, a house that Jack Built (1819), an anti-radical satirical pamphlet. The anonymous publication warns that ‘the mind is corrupted’ by Byron’s ‘sweet and harmonious’ poetry and says to ‘look at his feet’, a reference to his club-foot, for proof of his association with the devil.

This criticism was especially harsh given his lifelong sensitivity about his disability. Byron allegedly refused to sleep overnight in the same bed as many of his lovers so that they would not have an opportunity to observe his twisted foot.

Love

‘I cannot exist without some object of Love’. (Lord Byron to Lady Melbourne, 9 November 1812)

By his own account, Byron had many lovers, and most biographers agree that he had relationships with both women and men. Lady Caroline Lamb, the woman who famously labelled him ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’ in her journal, demanded to meet Byron after reading Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and went on to have a short-lived but zealous affair with him in 1812. After Byron ended the relationship because he felt it had become too public and intense, Lamb tried to stab herself and then sent Byron a snippet of her pubic hair in a letter signed ‘from your wild antelope’.[3]

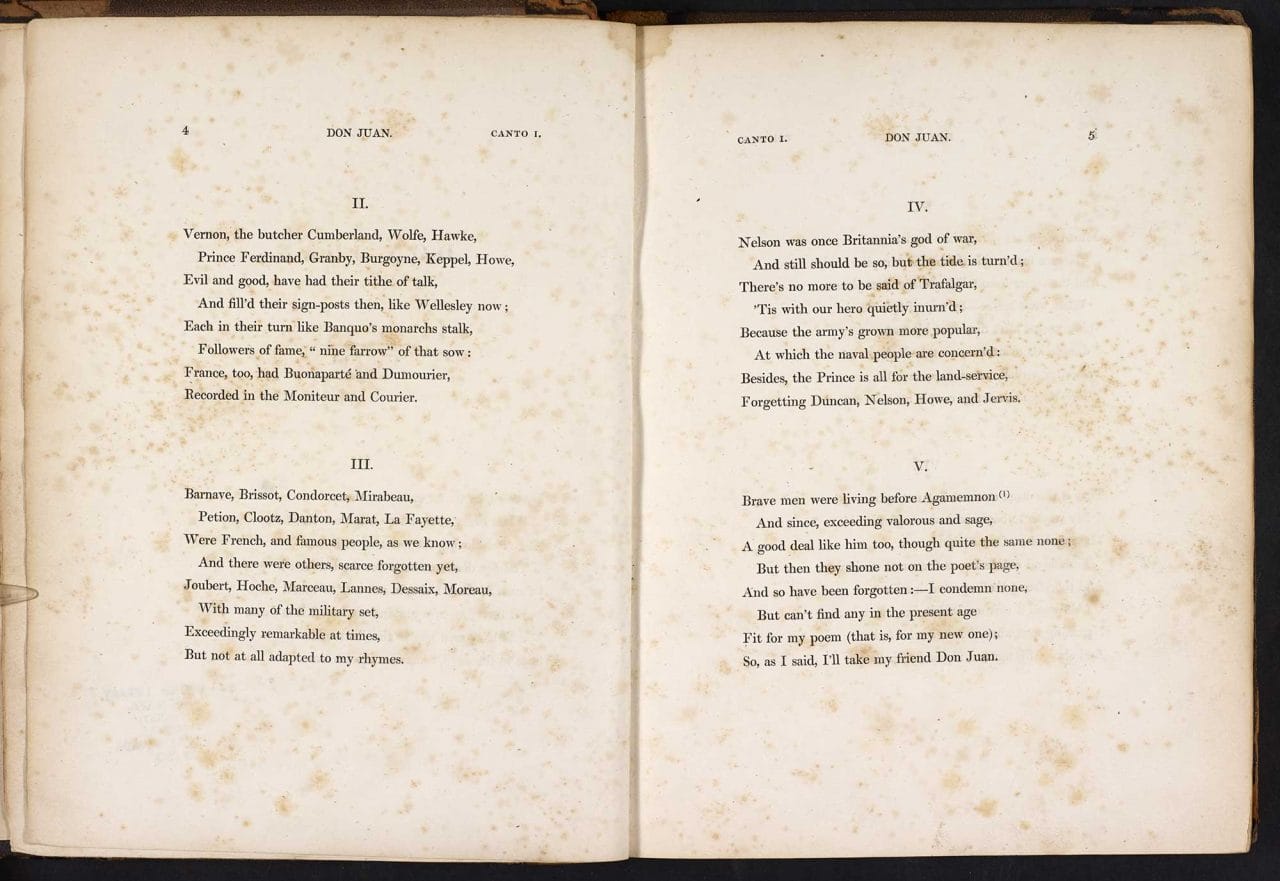

The fame that went along with the publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage brought many attestations of love, but love and poetry intertwined throughout Byron’s life. He claimed that his first attempt at poetry at the age of 12 was occasioned by the love of a cousin. And Don Juan, the epic poem he worked on for the last six years of his life and which was unfinished at his death, reimagines the legend of the prolific lover. He wrote to a friend about Don Juan, ‘it may be bawdy but is it not good English […] Could any man have written it – who has not lived in the world? – and tooled in a post-chaise? in a hackney coach? in a Gondola? Against a wall? in a court carriage?’ [4] His final days saw him enthralled by a young Greek boy of 15 who failed to return his affection. No longer the dashing and famous poet he once was, Byron found the teenager’s rejection a deep blow to his fragile ego, and his poetry from the time bears witness. His poem on the occasion of his 36th birthday, [5] his last, concludes ‘My days are in the yellow Leaf; / The flowers and fruits of Love are gone’.

Criticism

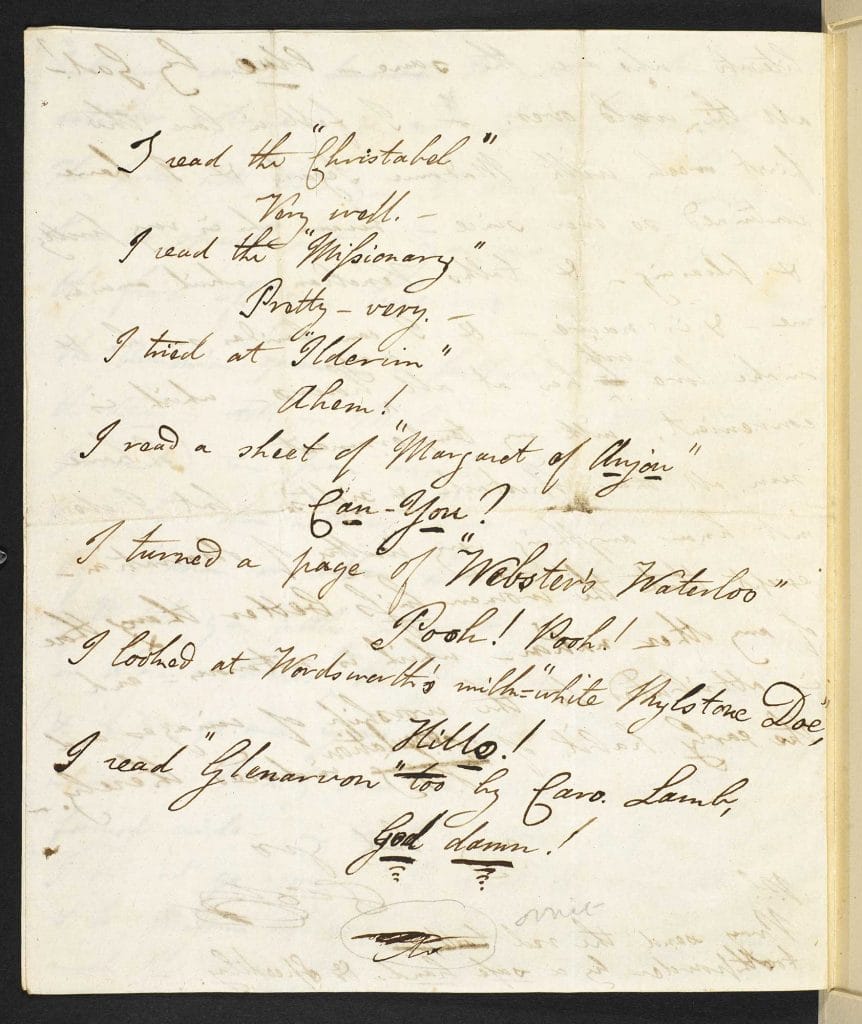

From his early publications, Byron provoked his contemporary poets by denouncing their writings. After receiving a harsh review of an early edition of his own poetry, Byron wrote the satire ‘English Bards and Scotch Reviewers’ (1809), which took aim at various poets, including Robert Southey, Walter Scott, and William Wordsworth whom he described variously as ‘little wits’ or ‘knaves and fools’. A letter to his publisher John Murray from 25 March 25 1817 when he was living in Venice includes an amusing poem that comments on the poems and novels of his contemporaries: Coleridge’s ‘Christabel’, William Lisle Bowles’ ‘The Missionary’, Margaret Holford’s ‘Margaret of Anjou’, and, most entertainingly, his ex-lover Caroline Lamb’s novel Glenarvon, which is a thinly veiled portrait of Byron.

I read the ‘Christabel’

Very well.

I read the ‘Missionary;’

Pretty – very.

I tried at ‘Ilderim;’

Ahem!

I read a sheet of ‘Margaret of Anjou;’

Can-You?

I turned a page of Webster’s ‘Waterloo’

Pooh! Pooh!

I looked at Wordsworth’s milk-white ‘Rylstone Doe’

Hillo!

I read ‘Glenarvon,’ too, by Caro. Lamb,

God damn!

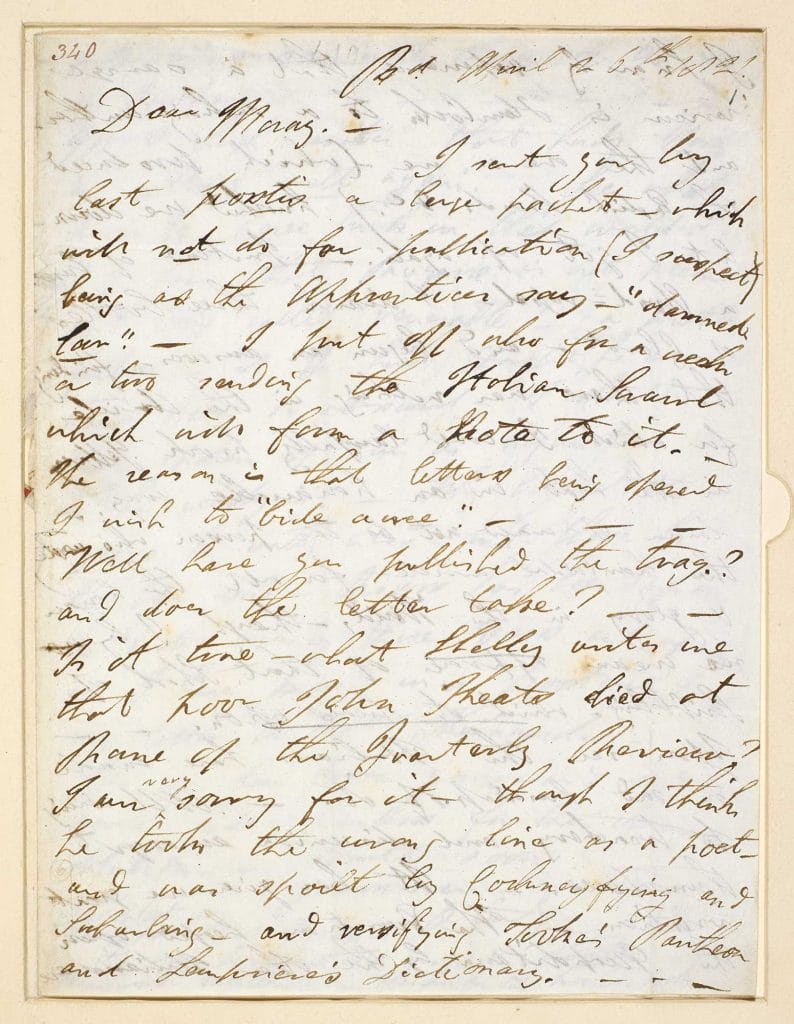

Byron was also famously dismissive of his fellow poet John Keats. In letters to his publisher Murray, Byron variously refers to ‘Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are’ [6] and to Keats’s writing as ‘a sort of mental masturbation’. [7] In a letter from 1821, Byron again expresses dislike of Keats’s poetry, although this time, it is tempered by Keats’s recent death, which was rumoured to be hastened by a bad review: ‘Is it true – what Shelley writes me that poor John Keats died at Rome of the Quarterly Review? I am very sorry for it – though I think he took the wrong line as a poet.’ [8]

The manuscript of the letter reveals that Byron inserted ‘very’ above the line ‘I am sorry’, an emphasis that regardless of its significance was certainly an afterthought.

One exception for Byron and his relationship with his contemporaries was his close friendship with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Byron praised Shelley’s poetry and Shelley his. In a letter from Shelley to ‘My dear Lord Byron’ in 1821, Shelley writes. ‘Many thanks for Don Juan. […] Nothing has ever been written like it in English, nor if I may venture to prophecy, will there ever be.’

脚注

- Lady Marguerite Blessington, Conversations of Lord Byron, ed. by Ernest J. Lovell Jr. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), p. 220.

- George Gordon Byron, The Works of Lord Byron including the suppressed poems complete in one volume (Paris, A. and W. Galignani, 1828), p. 555.

- Leslie A Marchand, Byron: A Portrait (London: John Murray, 1971), p. 130.

- London, British Library, Add MS 42093, 26 October 1819.

- The full title of this poem is 'On this Day I complete my Thirty-Sixth Year'.

- London, British Library, Ashley MS 5160, 4 November 1820.

- London, British Library, Ashley MS 5161, 9 November 1820.

- London, British Library, Ashley MS 4747, 26 April 1821.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Clara Drummond

Clara Drummond is an independent curator and writer based in Belgium. She has a PhD in Editorial Studies from Boston University and was previously a Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts at The Morgan Library & Museum in New York. She has curated major exhibitions on Jane Austen and Animals in Art, Literature, and Music and published essays on Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the history of classical translation. She is currently working on a book on the material and cultural history of letter writing.