Charlotte Brontë: mixing the familiar and the fantastic

In her writing as a child and as a young schoolteacher, Charlotte Brontë moved effortlessly between ordinary and imaginary worlds. Professor John Bowen explores how this dual existence made its way into her novel Jane Eyre.

Professor John Bowen and Ann Dinsdale discuss the fantasy worlds of Gondal and Angria, created by the Brontë children, and the lasting influence of these on the sisters’ later novels. Filmed at the Brontë Parsonage, Haworth.

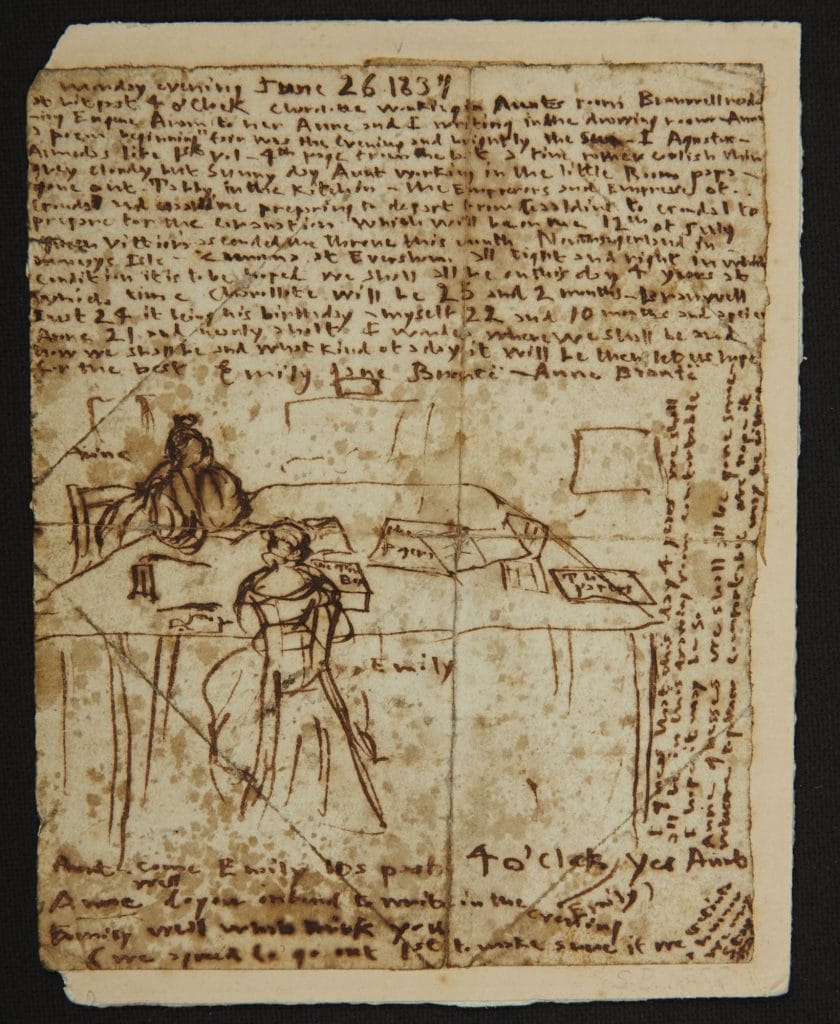

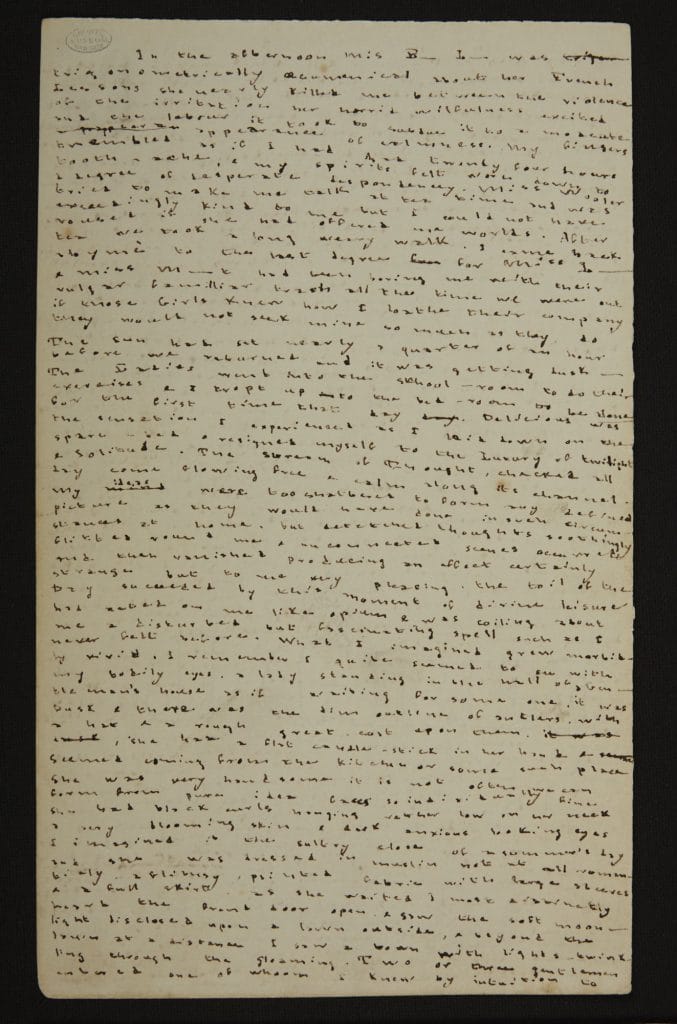

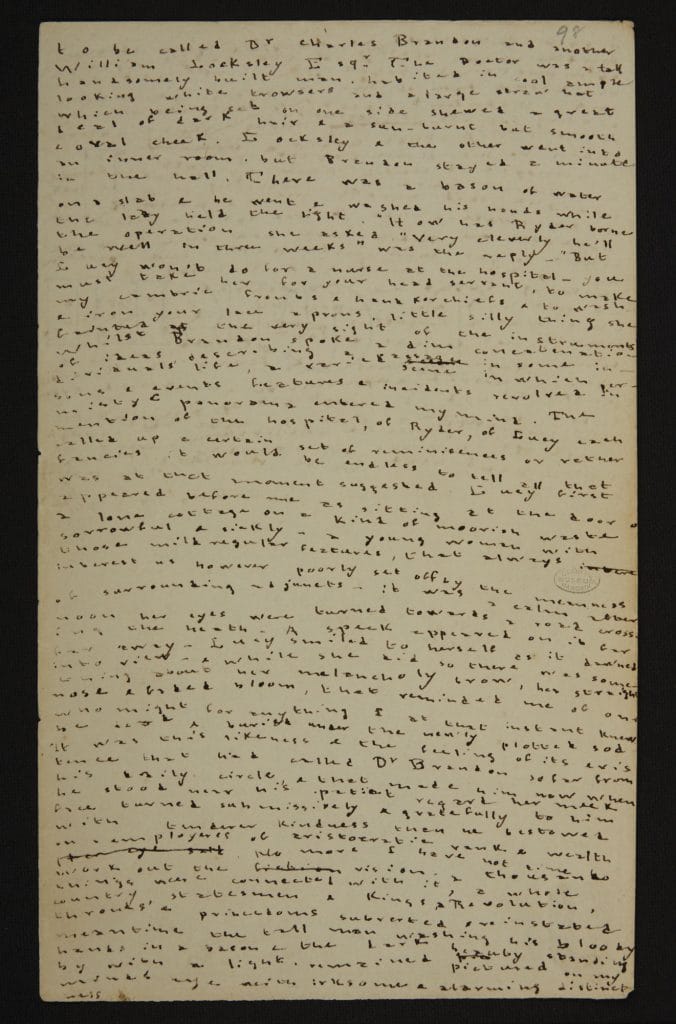

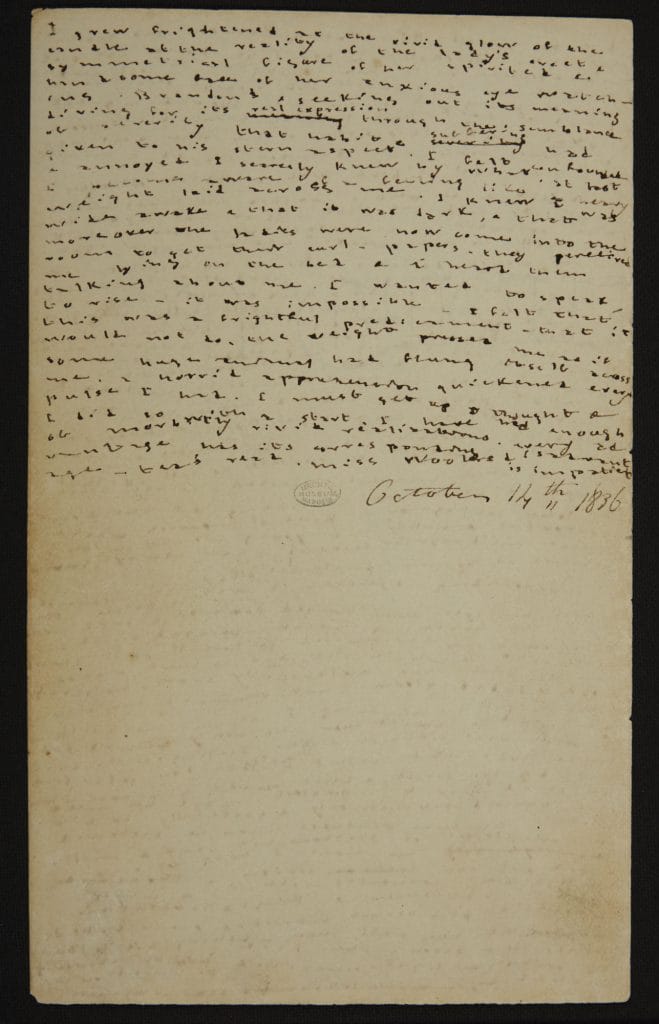

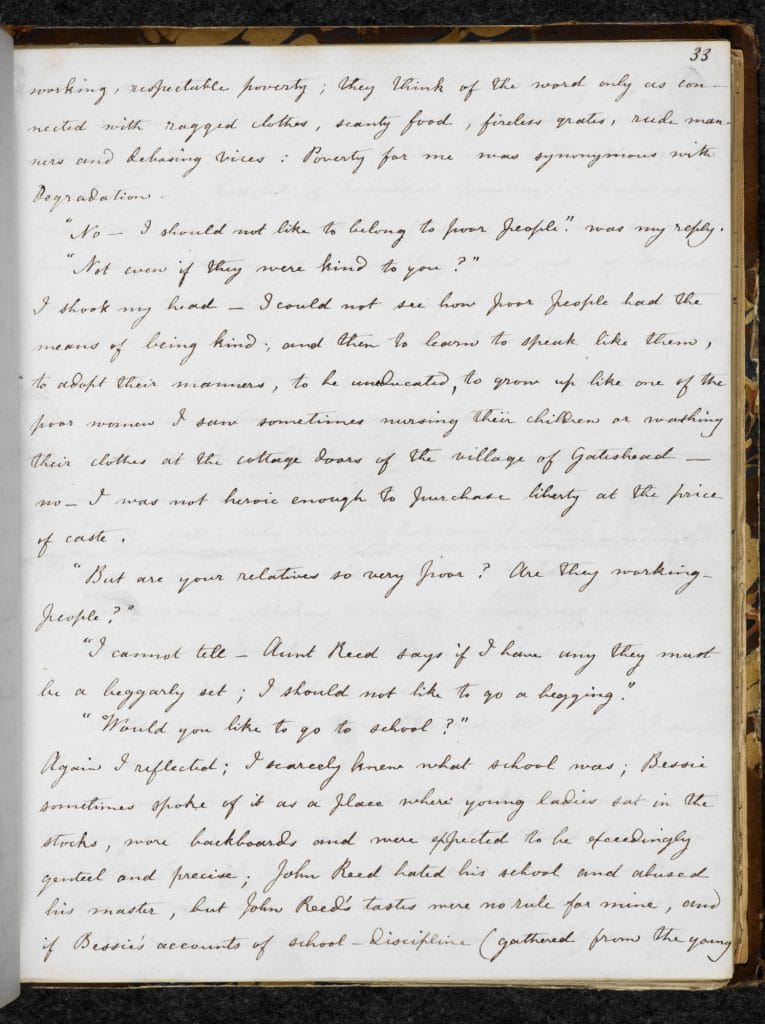

Few novelists of the period were as fascinated as Charlotte Brontë by the power of fantasy or aware of its complicated relationship to everyday life. The Brontë children left behind a remarkable archive of handwritten manuscripts, several of which are shown on this website. Charlotte and Branwell, and Emily and Anne, collaborated on the creation of two extraordinary fantasy lands, Angria and Gondal respectively, the life of which they recorded in dozens of stories, magazines, maps and drawings. They were often written in tiny books made out of pieces of scrap paper, such as wallpaper and sugar bags, small enough for their toy soldiers to read. The contents of these stories were an extraordinary mix of dramatic, violent and sometimes erotic happenings on the one hand and everyday events on the other.

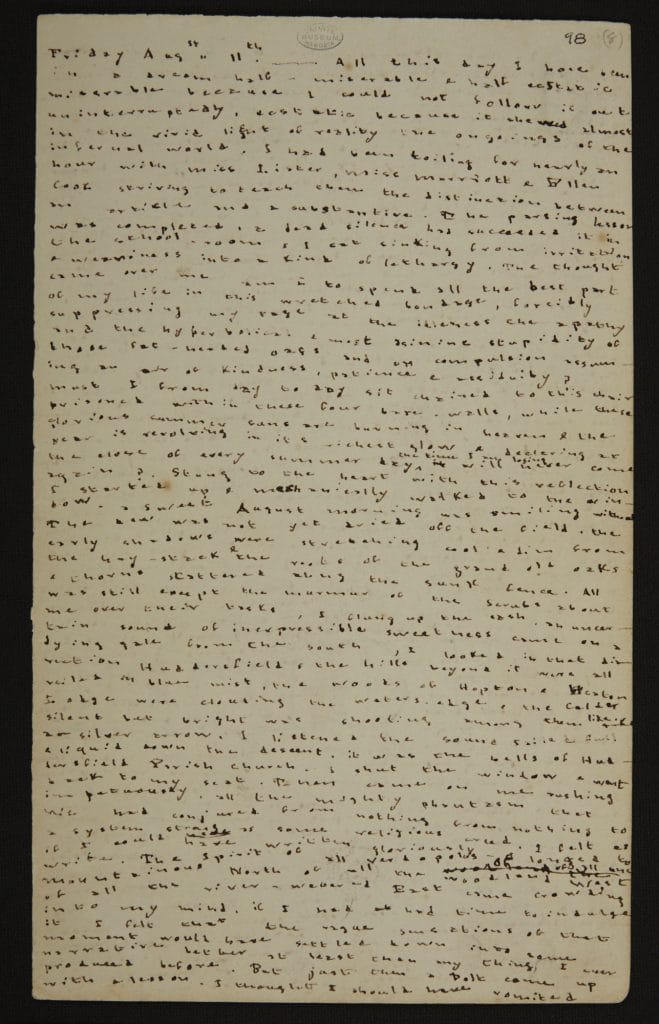

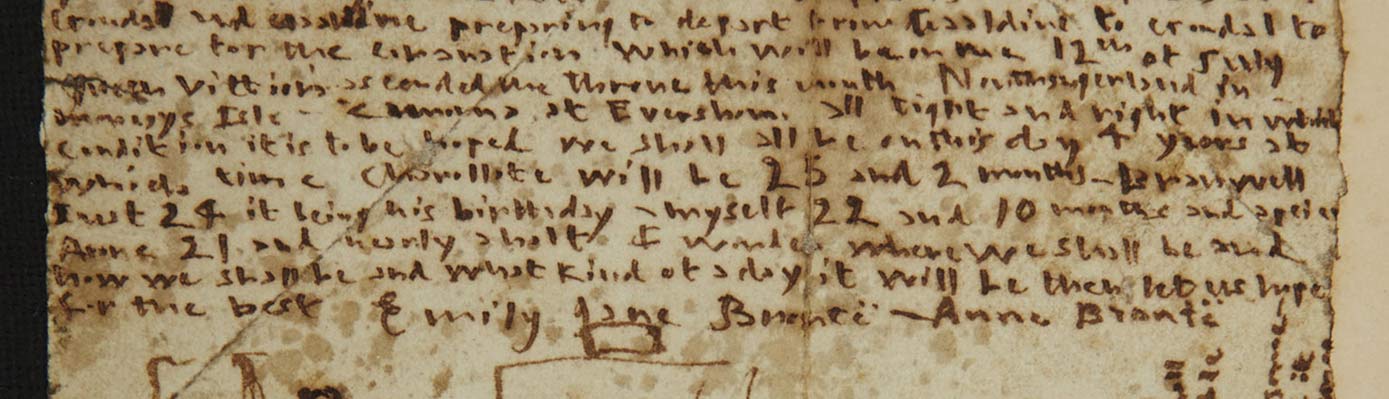

One ‘diary paper’ from June 1837 seamlessly moves from mentioning Queen Victoria’s recent ascension to the throne to describing the coronation of the fictional Queen of Gondal. Charlotte Brontë’s diary, kept when she was a schoolteacher at Roe Head school, records both imaginary happenings in Angria and the banalities of her everyday life as a teacher:

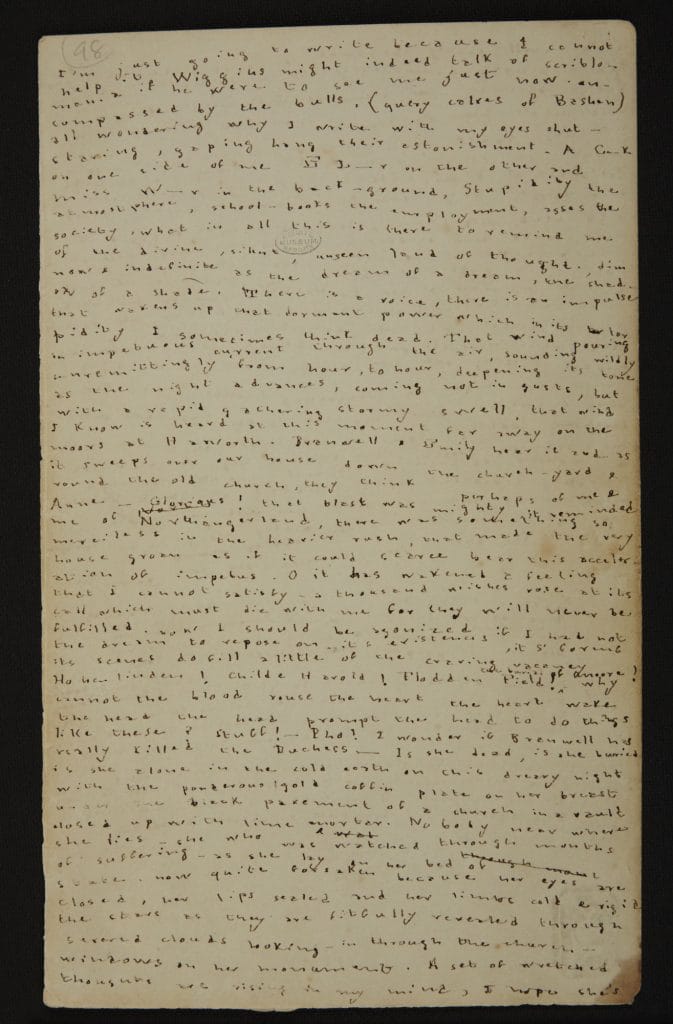

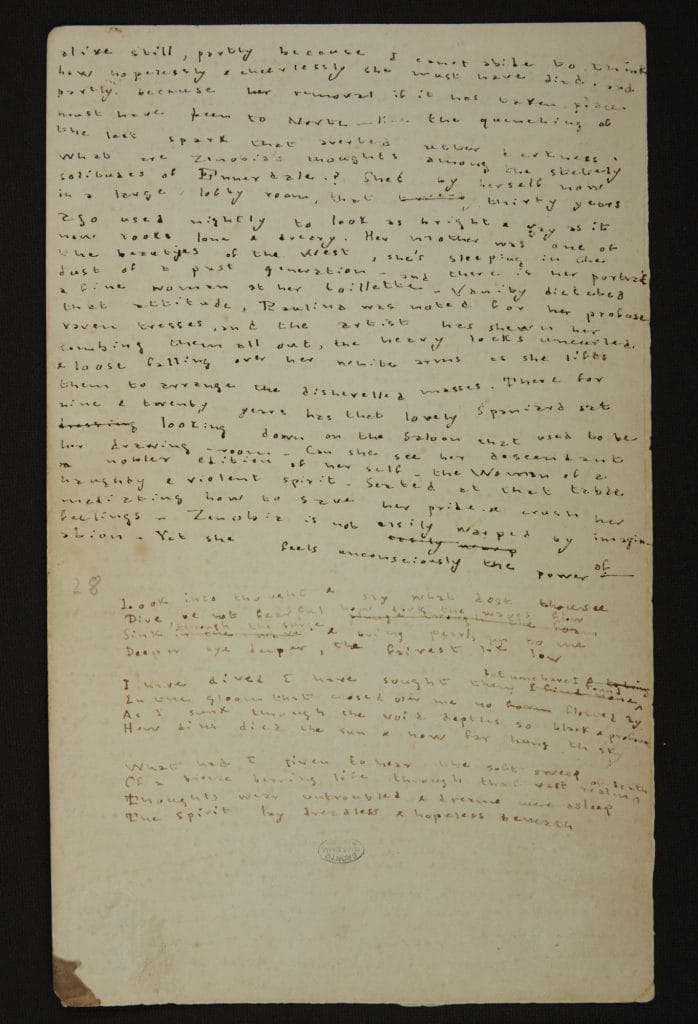

What I imagined grew morbidly vivid,…All this day I have been in a dream, half miserable and half ecstatic: miserable because I could not follow it out uninterruptedly; ecstatic because it shewed almost in the vivid light of reality the ongoings of the infernal world. …Then came on me, rushing impetuously, all the mighty phantasm that we had conjured from nothing to a system strong as some religious creed. I felt as if I could have written gloriously – I longed to write. The spirit of all Verdopolis, of all the mountainous North, of all the woodland West, of all the river-watered East came crowding into my mind. If I had had time to indulge it, I felt that the vague sensations of that moment would have settled down into some narrative better at least than any thing I ever produced before. But just then a dolt came up with a lesson. I thought I should have vomited. [1]

Two very different kinds of writing, thought and being coexist here. On the one hand, there is a simple conversational intimacy with the reader that tells us about the humdrum world of provincial school teaching. On the other, there is a hallucinatory vision of Angria. The latter is a world of primal emotions – shame, pride, revenge, ‘ambition, tyranny, licentiousness, insolence, avarice, bold-thirstiness, bad faith’ [2] – and of a bi-sexual eroticism so shocking that it gave Charlotte’s friend and fellow novelist Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-65) ‘the idea of creative power carried to the verge of insanity’.[3] Everyday life suddenly punctuates fantasy and closes off its pleasures, and Brontë tells us about both. It is often hard, though, to know what relationship reality and fantasy have at this moment and more generally in her work. Is the tone here ironic, exasperated or comically self deflating? Does it signal the defeat of superheated fantasy by everyday life or something more complex?

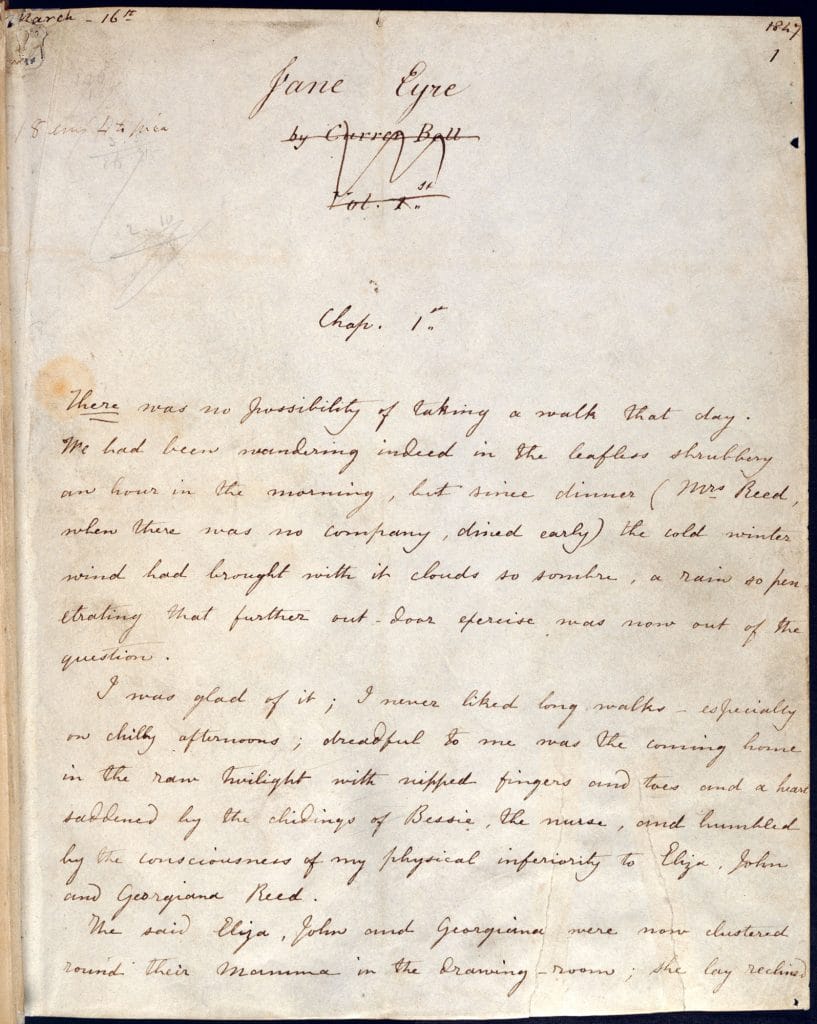

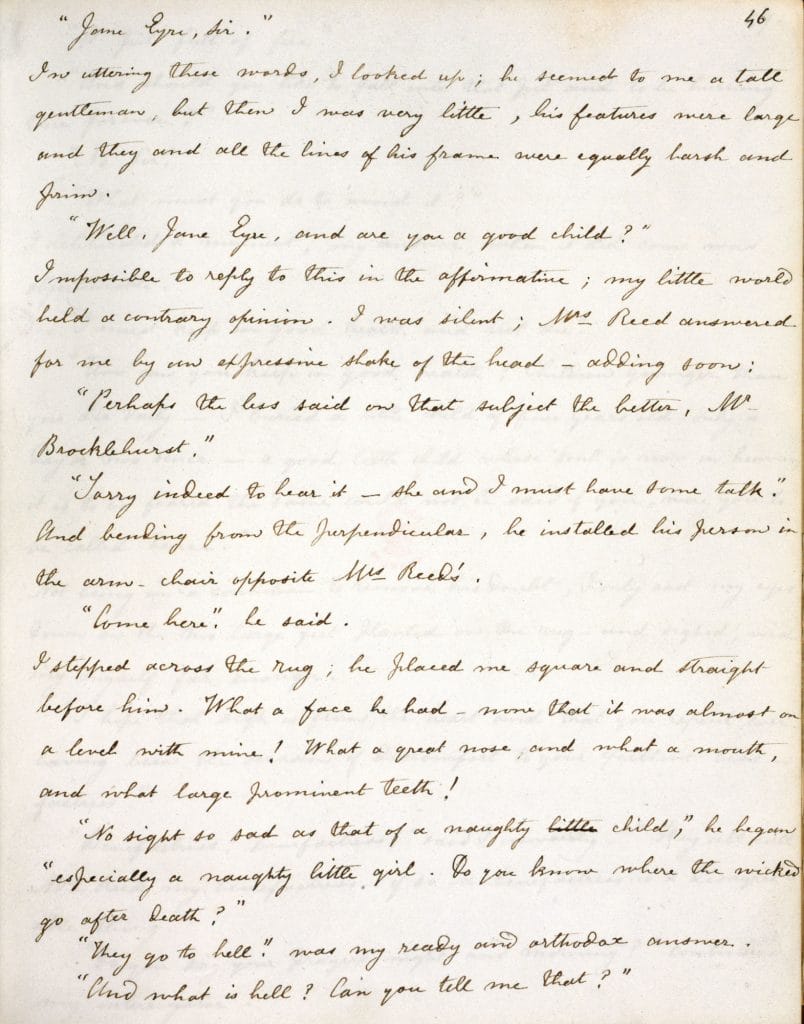

Jane Eyre – mixing styles

This mix of qualities can be seen even more deeply in Jane Eyre (1847). It is an archetypal, if not the archetypal, romance in English fiction, and the model for countless conscious and unconscious imitators. When Jane as a child resists the bullying of John Reed, she exclaims: ‘Wicked and cruel boy! … You are like a murderer – you are like a slave-driver – you are like the Roman emperors!’ I had read Goldsmith’s History of Rome, and had formed my opinion of Nero, Caligula etc.’ (ch. 1) It is an act of self-assertion by Jane, in and through the power of reading and identification. She violently rebels against the injustice of her particular fate, but equally strongly seeks to persuade us that it is typical and representative.

This is how many of the novel’s uses of fairy-tale motifs and fantasy gain their power. When Jane is first shown round Thornfield, she asks if there are any ‘legends or ghost stories’ about the house. ‘None that I ever heard of’ is Mrs Fairfax’s reassuring reply; but Jane immediately compares a passage-way in the house to ‘a corridor in some Bluebeard’s castle’. In the legend, of course, Bluebeard murdered his virgin brides and forbade his new wife to enter one particular room in which their corpses were placed. Immediately after making the comparison, Jane first hears the ‘curious laugh’ of Rochester’s first wife, Bertha Mason that announces the terrible secret of the house. We are in a realistic world, without ghosts, legends or murderous husbands, but we are repeatedly invited to think that the supernatural, the Gothic or fairy-tales may help us understand its deepest and most important workings. Jane senses something significant at this moment that will determine her whole future fate. It is not the force of the supernatural, but it nevertheless cannot beexpressed in simply rational or common-sense terms. There are many examples of this: Rochester’s dog, for example, is compared to the legendary creature, the Gytrash; Jane is described by him as someone who comes ‘from the abode of people who are dead’. Each of these examples is simultaneously both mystifying and revealing; they never allow us to settle into knowing exactly what kind of story we are being told, or of knowing in what way it will resolve itself.

Much of the force of the book stems from the play of opposing qualities, in a world of primordial states of feeling. It is often a very melodramatic book, which finds value and meaning through impassioned conflicts between the hope and possibility of authenticity and fulfilment for Jane on the one hand, and renunciation and loss on the other. Many of the most important scenes of the book are forms of trial, that both test Jane’s endurance and integrity and reveal injustice or wrong. These scenes often lead to bodily suffering and symptoms, such as nervous shock or pain. They also lead to deep divisions and uncertainties of the self: when Jane returns to Rochester after visiting her dying aunt, she feels as if ‘every nerve is unstrung: for a moment I am beyond my own mastery’. The self and the body are never secure in Jane Eyre, but often taken to (or even beyond) its limits. Courageous in its description of pain and violence, the novel is fascinated by how physically powerfully emotions and sensations can be: Rochester in chapter 15 describes jealousy as ‘the green snake …rising on undulating coils from the moonlit balcony, [that] ate its way in two minutes to my heart’s core’. Against the oppressive moralism and rejection of the body that the Rev. Brocklehurst advocates, the novel and its leading characters constantly emphasises the desires and needs of the embodied self.

脚注

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: John Bowen

John Bowen is a Professor of 19th century literature at the University of York. His main research area is 19th-century fiction, in particular the work of Charles Dickens, but he has also written on modern poetry and fiction, as well as essays on literary theory.