Jane Eyre and the rebellious child

Drawing on children’s literature, educational texts and Charlotte Brontë’s own childhood experience, Professor Sally Shuttleworth looks at the passionate and defiant child of Jane Eyre.

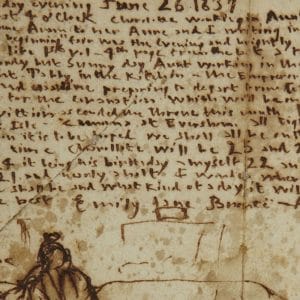

Professor John Bowen and Ann Dinsdale discuss the childhood writings and experiences of the Brontë sisters, exploring how these shaped their later writing in novels such as Jane Eyre. Filmed at the Brontë Parsonage, Haworth.

I am glad you are no relation of mine: I will never call you aunt again as long as I live. I will never come to see you when I am grown up; and if any one asks me how I liked you, and how you treated me, I will say the very thought of you makes me sick, and that you treated me with miserable cruelty. (ch. 4)

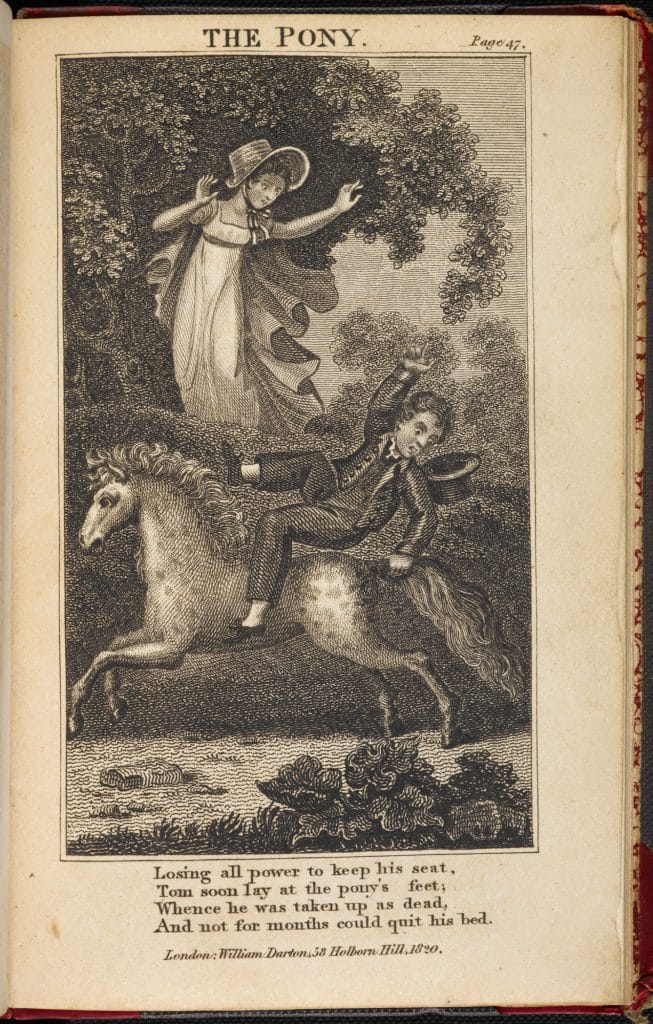

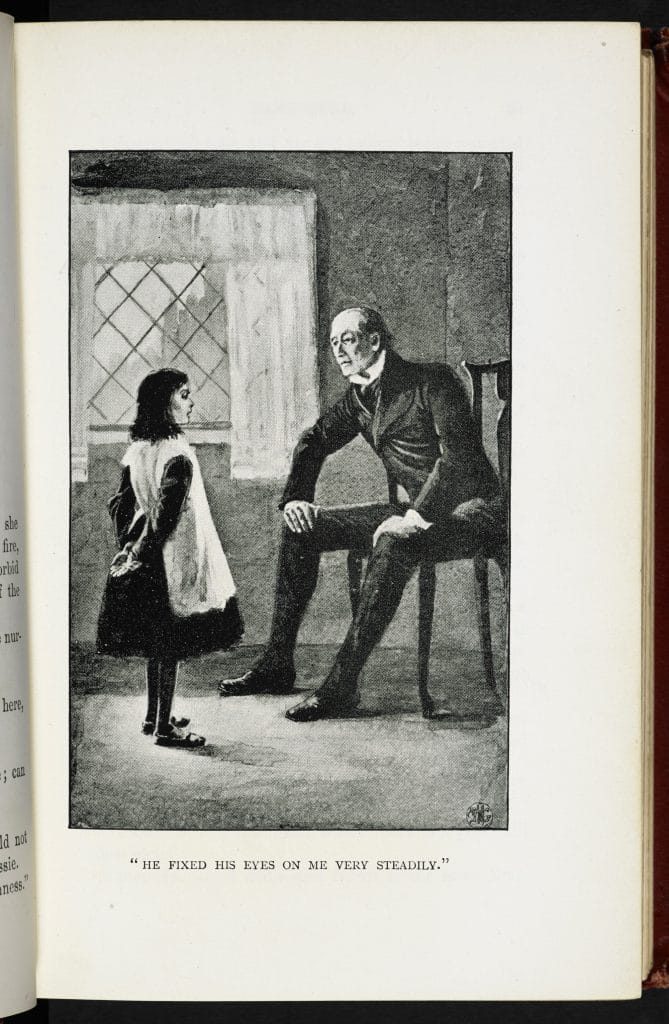

When Jane Eyre was published in 1847, it introduced a new voice to the world – a passionate, angry and defiant child. There were many passionate children in the moral instruction books designed for children in the early decades of the 19th century, but in these cases, they were examples of bad or sinful behaviour. Such children had to mend their ways, or suffer a terrible fate. In the case of Jane Eyre, however, Charlotte Brontë clearly expected her readers to be on the side of her defiant child as she stands up to adult tyranny.

Passion and disobedience

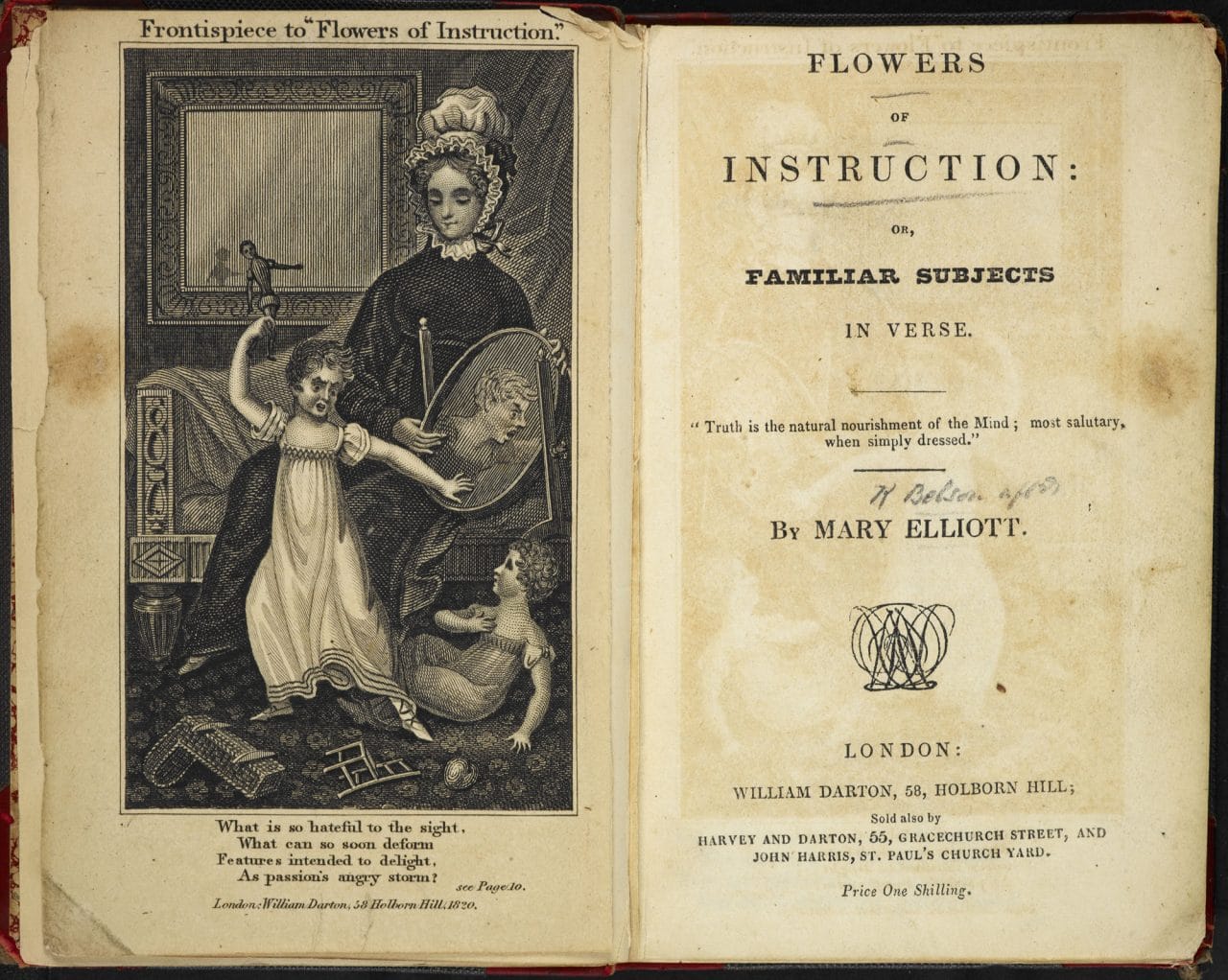

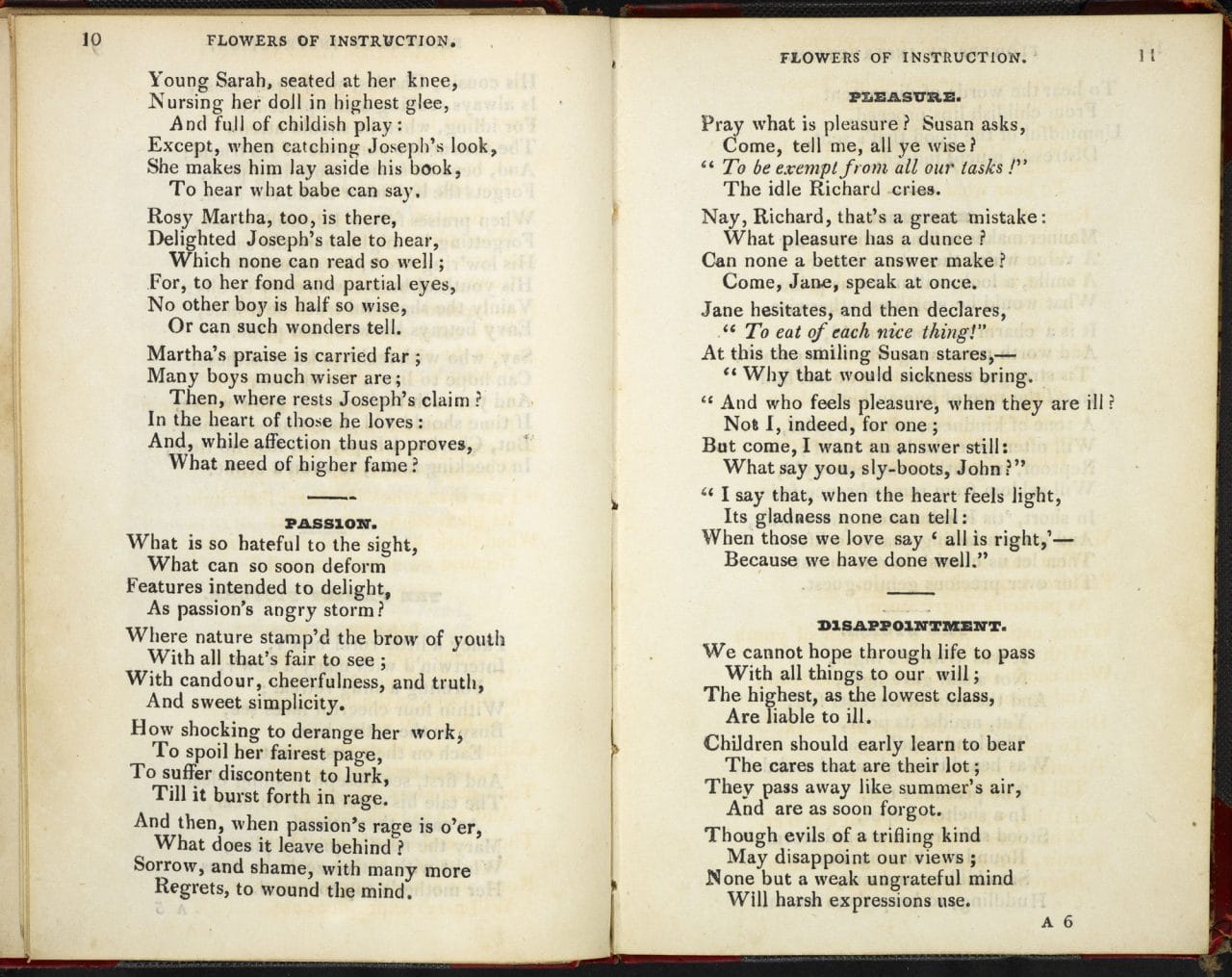

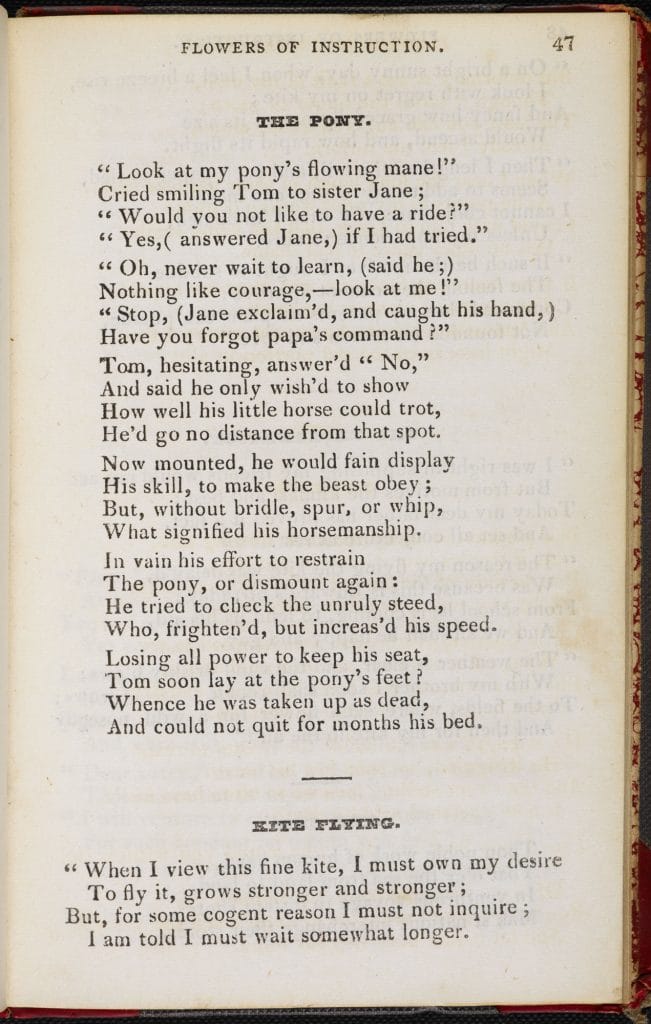

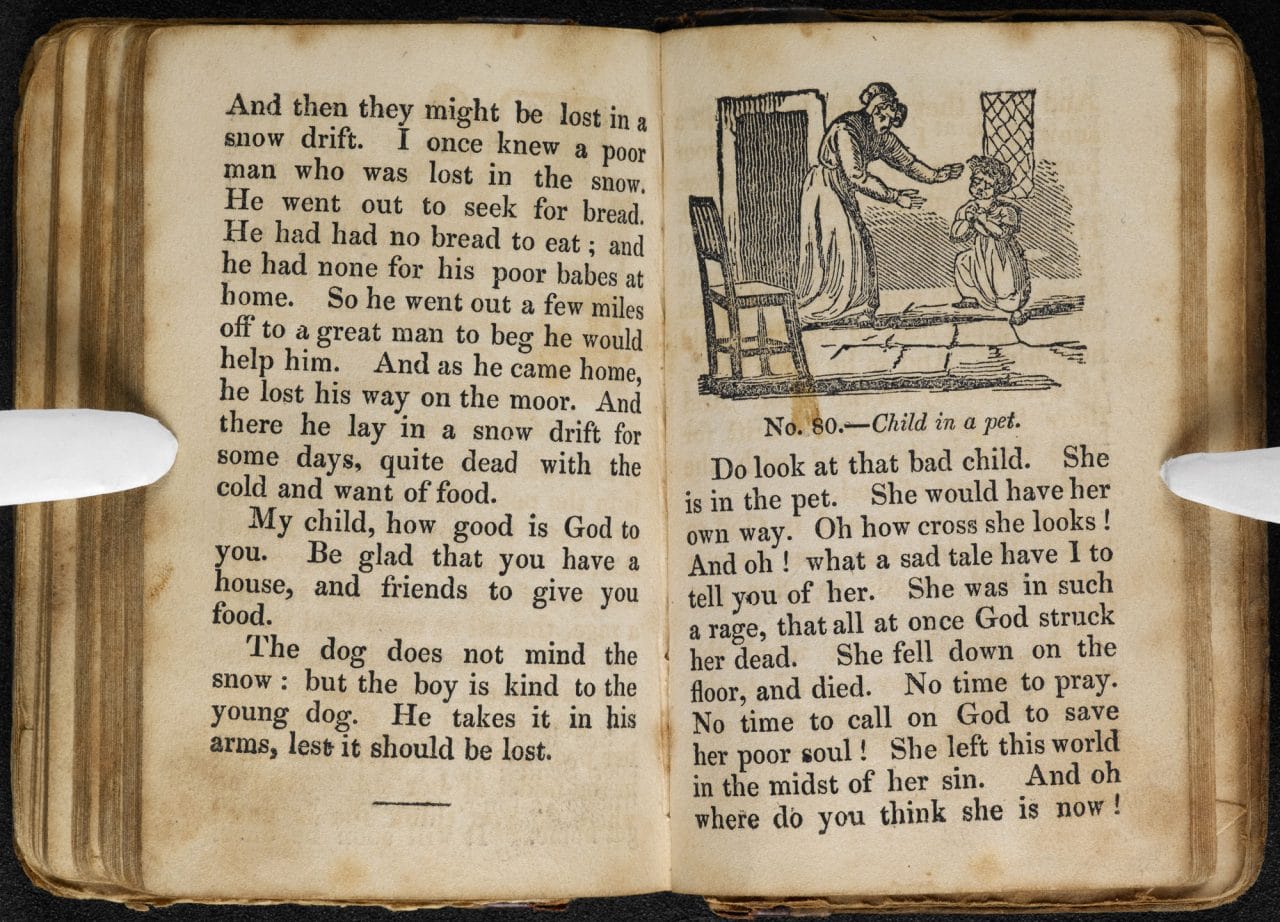

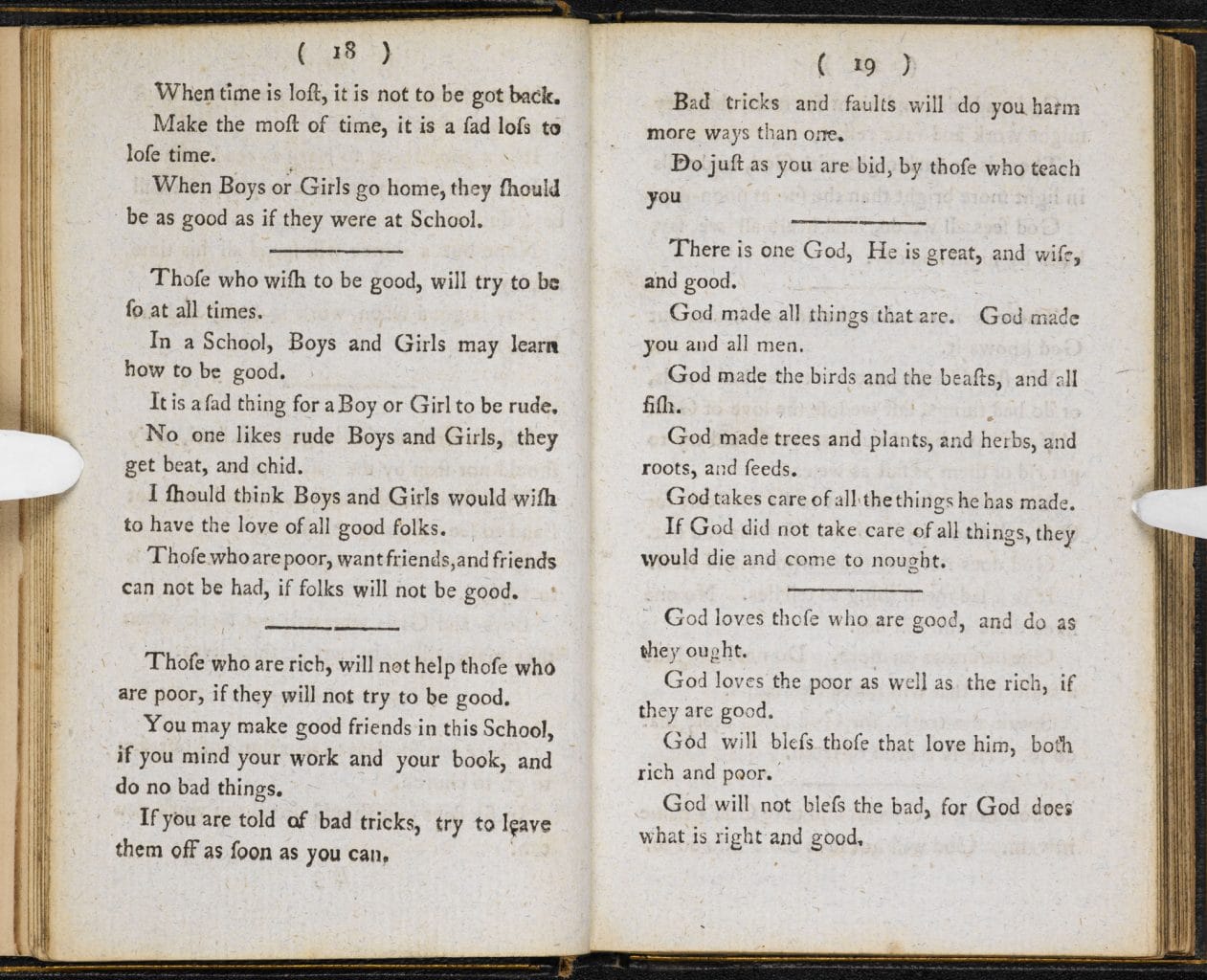

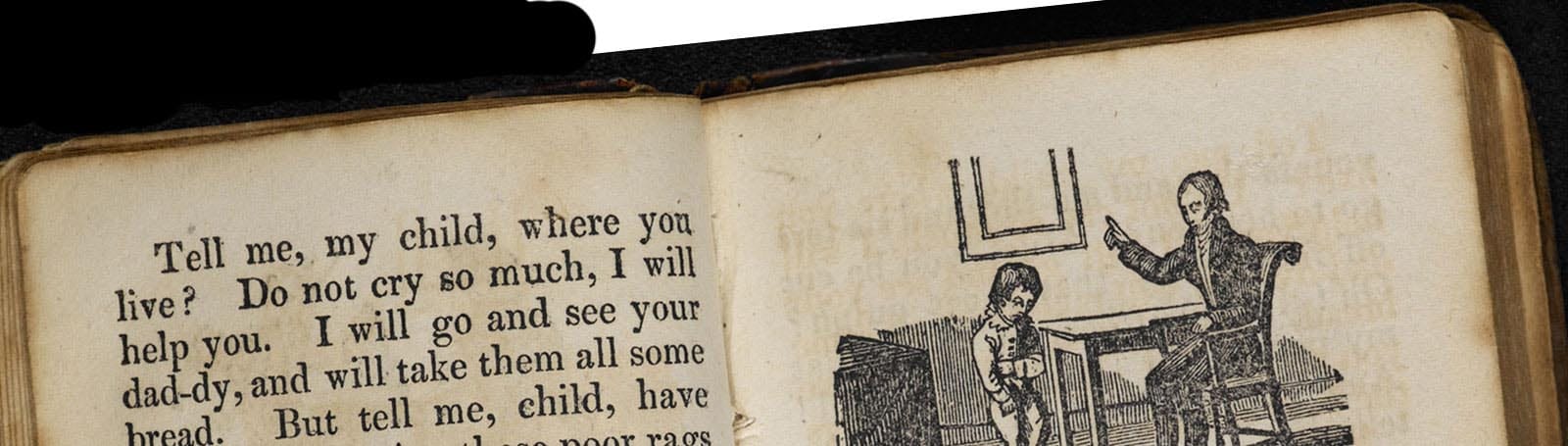

Jane Eyre was one of the first novels that set out to explore what it feels like to be a child: unlike Charles Dickens’s slightly earlier work, Oliver Twist (1838), it is recounted by the heroine herself, supposedly in adulthood, but with all the intensity of immediate experience. On the very first page we learn that Jane is set apart from her cousins by her aunt who wants her to acquire ‘a more sociable and child-like disposition’. Her aunt clearly has in mind the sort of child depicted in the instruction books for children such as Ellen, or the Naughty Girl Reclaimed (1811) , a picture book with a cut-out dunce’s cap. Here a naughty child, who throws away her schoolbook, learns to control herself and to become a quiet, obedient daughter, who is ‘anxious her dear mamma to please’. Another example, from Flowers of Instruction (1820), shows an angry child who is jealously attacking her little sister or brother, but learns from her mother to control ‘passion’s angry storm’. Children who did not control themselves could descend, it was warned, into a life of crime, or even worse, medical books suggested, into complete mania in adulthood.

Unlike these naughty children from the morally improving literature, Jane is a defiant child, who is fully convinced of the rightness of her rebellion. She likens her mood to that of a ‘rebel slave’ with her ‘heart in insurrection’ (ch. 2). Subtle connections in language are thus created with the figure of Rochester’s ‘mad wife’, who we will meet later on, who is of mixed race, and from the slave-owning West Indies. In her anger and passion, Jane is far removed from the conventional model of the Victorian child who should be ‘seen and not heard’. Instead, she is part of new, emerging, more sympathetic attitudes to childhood, which stressed that adults should pay attention to the feelings and sufferings of children. They were not just blank slates until adulthood, but capable of even more intense emotional suffering than adults. In her book, Household Education (1849), the writer Harriet Martineau noted that it had not been fully understood how much a child can suffer from fear, and few parents ‘know anything of the agonies of its little heart, the spasms of its nerves, the soul-sickness of its days, the horrors of its nights’. Her description of her own terror of a magic lantern, and the shadows it cast, offers remarkable parallels with Jane’s terror of the flickering light when she is locked in the red room. (ch. 10, Care of the Powers – Fear)

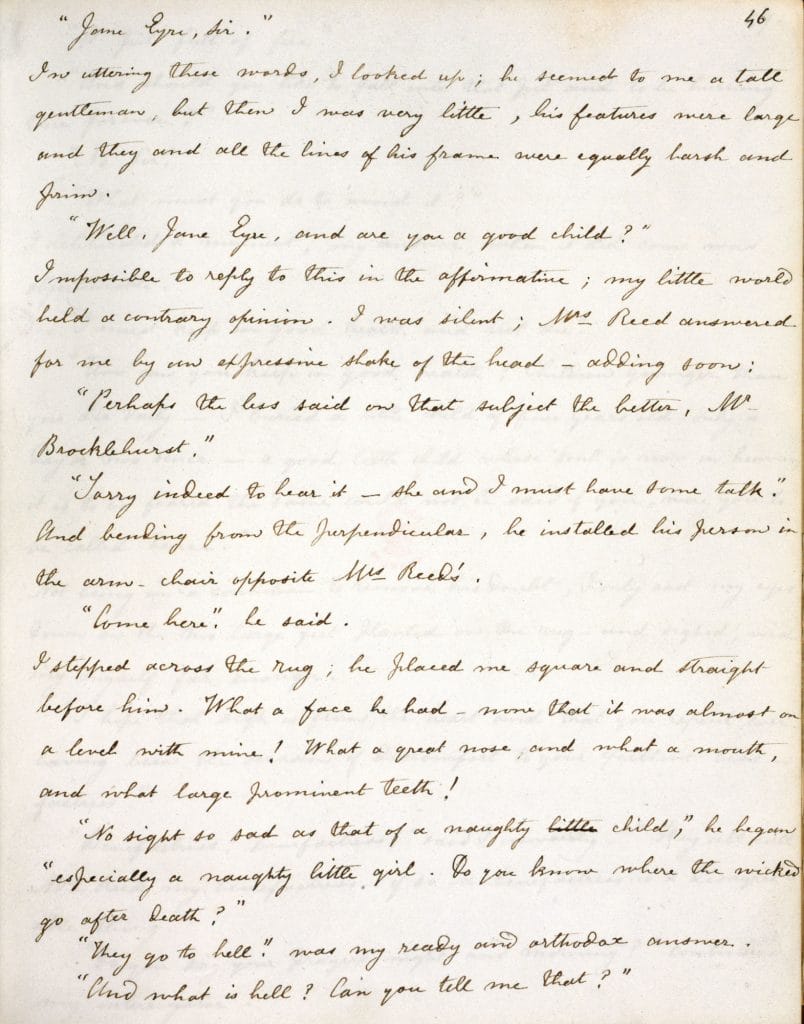

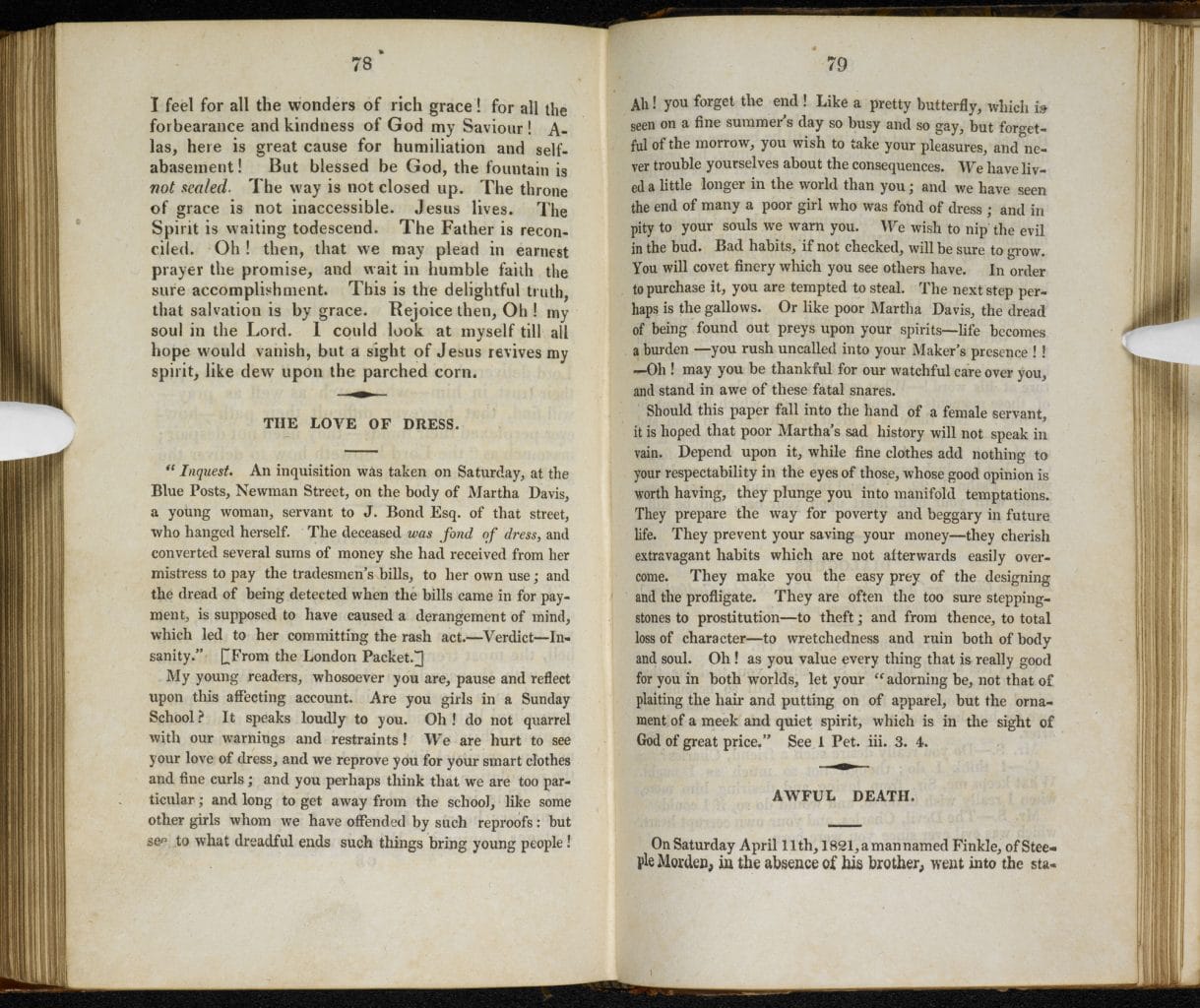

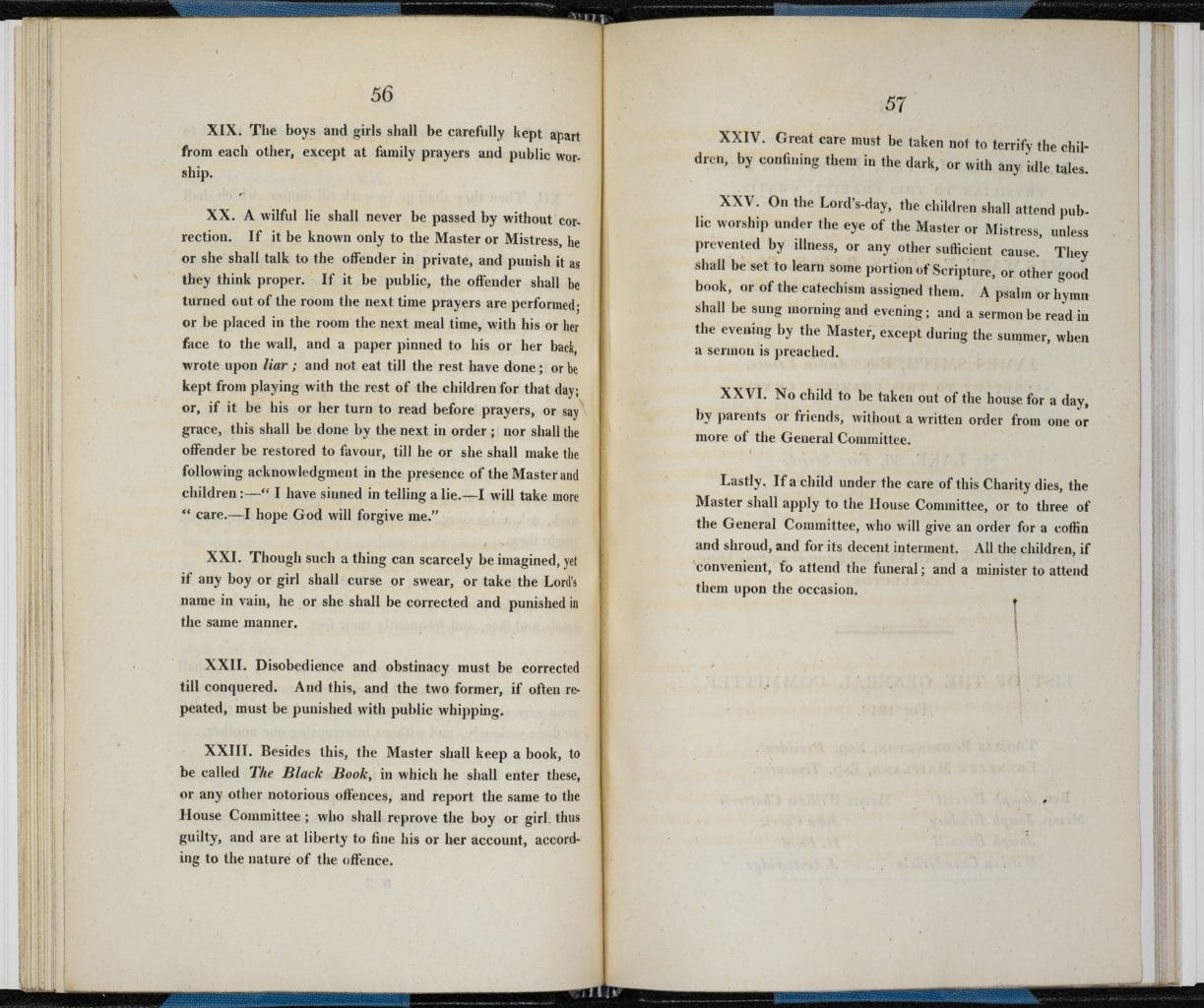

Lowood and the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge

When Jane is sent away to school by her aunt, she hopes her life will improve, but she is mistaken. Lowood Institution is partly based on the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, which Charlotte Brontë attended with her older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, and younger sister Emily, in 1824-25. Maria and Elizabeth died of consumption, contracted at the school, and there was also an outbreak of typhus while Charlotte was there, which clearly helped to colour her memories of Cowan Bridge. When the Reverend Brontë sent his daughters there, however, he had every reason to believe it would be a good school, and indeed it was not that different from other similar institutions. Lowood Institution, as depicted by Brontë, was harsh, but far removed from the dreadful Yorkshire school, Dotheboys Hall, in Dickens’s novel Nicholas Nickleby (1839). The dominating Mr Brocklehurst was partly based on the evangelical clergyman, the Reverend Carus Wilson, who ran Cowan Bridge. The ‘Child’s Guide’ Brocklehurst gives to Jane, which contained ‘an account of the awfully sudden death of Martha G—, a naughty child addicted to falsehood and deceit’ (ch. 4) is no doubt based on some of Carus Wilson’s own publications, either Child’s First Tales (1836), or his magazine, The Children’s Friend, which both carried many tales of children who were struck down dead if they flew into a passion, or told lies. Brocklehurst makes Jane stand on a stool in front of the class and orders her classmates to shun her because she is a liar. The novelist Elizabeth Sewell recalls how, at her school in the 1820s, girls who told a lie were made to stand in a black gown with a picture of a liar’s tongue round their neck. (Sewell, Autobiography, 1907, pp. 13-14) The main idea behind these harsh measures was that if the body was punished, the soul could be saved. In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë challenges these notions, and instead offers a deeply sympathetic portrayal of a rebellious child, which helped to transform Victorian attitudes to the child.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Sally Shuttleworth

Sally Shuttleworth is Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford, where she specialises in Victorian literature and the inter-relations of literature and science. Her published works include Charlotte Brontë and Victorian Psychology and The Mind of the Child: Child Development in Literature, Science and Medicine, 1840-1900. She has also published Oxford World’s Classics editions of Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey.