Cities in modernist literature

The alienated modernist self is a product of the big city rather than the countryside or small town. Katherine Mullin describes how an interest in the sensibility associated with the city – often London, but for James Joyce, Dublin – developed from the mid-19th century to the modernist period.

There is something distasteful about the very bustle of the streets, something that is abhorrent to human nature itself. Hundreds of thousands of people of all classes and ranks of society jostle past one another; are they not all human beings with the same characteristics and potentialities…? And yet they rush past one another as if they had nothing in common or were in no way associated with one another…The greater the number of people that are packed into a tiny space, the more repulsive and offensive becomes the brutal indifference, the unfeeling concentration of each person on his private affairs.

Frederick Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845).

The city is a key motif in modernist literature. Numerous novels and poems reflect the ways in which cities generate states of shock, exhilaration, alienation, anonymity, confusion or thrill. The idea of the isolated, questioning self belongs to the modern urban centre, not the provincial margins, a subject famously explored by the 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire celebrated the flâneur, a leisured wanderer who was able inconspicuously to observe the vivid modern city. Far from being repelled by the crowd as in the passage by Engels above, the flâneur revels in the sense of anonymity he experiences while drifting through a stream of people. In his 1863 essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ Baudelaire offered a profile of ‘The Man of the Crowd’:

The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and infinite. [1]

Loitering, lingering, strolling and looking, the flâneur indulged in this modern hobby: ‘botanising on the asphalt’, as Walter Benjamin later put it.[2] The flâneur was no mere tourist or gawker, but a sophisticated native, practising ‘gastronomy of the eye’. Selective, intelligent, scrutinising to infer, he was a detective, reading the urban landscape for clues. As Benjamin wrote: ‘Baudelaire speaks of a man who plunges into the crowd as into a reservoir of electric energy…he calls this man “a kaleidoscope equipped with consciousness”.[3]

London’s fogs

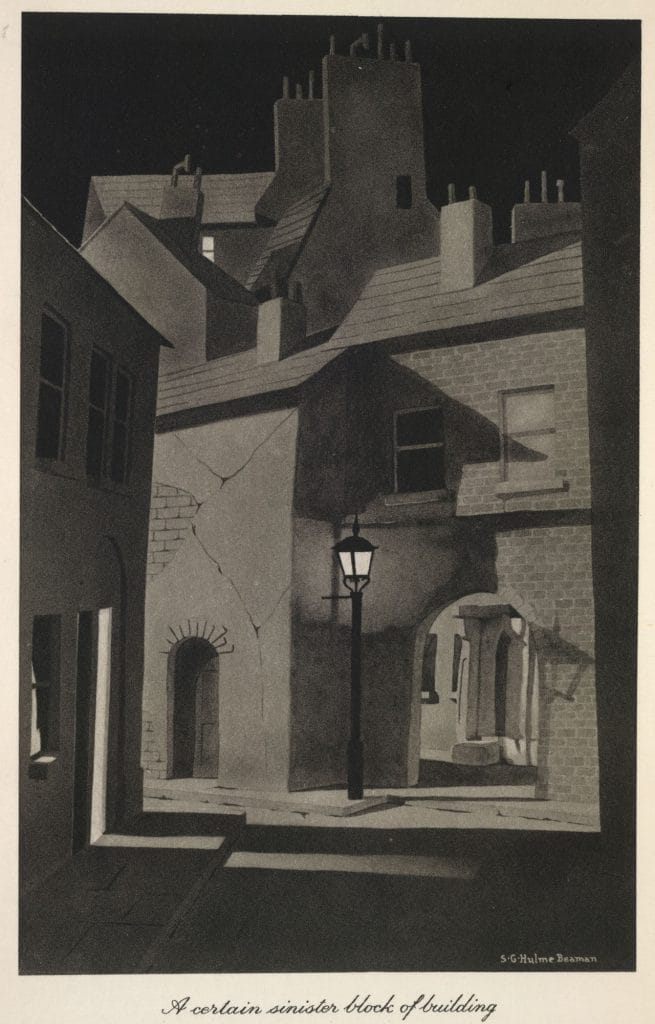

For Baudelaire, the flâneur‘s talents were fascinatingly distilled in Edgar Allen Poe’s 1840 short story ‘The Man of the Crowd’. The tale concerns a nameless narrator, sitting in a London coffee shop and watching the crowds, until he is drawn to pursue a stranger, an oddly dressed old man with a compelling face suggestive of ‘the type and genius of deep crime’. Poe’s narrator is a prototype of his later detectives, and the detective became a new version of the flâneur and a widely used literary motif. Between 1831 and 1925, London was the largest city in the world, and its labyrinthine geography and disorientating fogs were suited to fictions about the opacities of modern life. Robert Louis Stevenson‘s 1886 novella, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, acquires menace and mystery from a hybrid setting — a London-resembling Edinburgh — where mornings are overcast with dark fog, and the main action takes place against the ‘great field of lamps of a nocturnal city’.[4] In Arthur Conan Doyle‘s The Sign of Four (1890), imperial adventure is transposed to a London that is as resistant to understanding as the faraway Empire. Travelling with Sherlock Holmes to an appointment that will set the plot in train, Dr Watson soon loses his bearings, perplexed by ‘a dense drizzly fog which lay low over the great city,’ the ‘yellow glare from the shop-windows’ and ‘something eerie and ghostlike in the endless procession of faces’.[5] Watson’s confusion casts Holmes’s confidence into relief, for it is through Holmes’s miraculously encyclopaedic knowledge of this slippery city that the conspiracy is unravelled.

Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907) amplifies slipperiness in a disorientating detective plot set against a bewilderingly liquid London. Attempting to discover the truth behind a terrorist plot to blow up the Greenwich Observatory, the assistant commissioner leaves his office to find ‘His descent into the street was like the descent into a slimy aquarium from which the water had been run off’. [6]

Winnie Verloc is at the heart of the riddle, and she too finds ‘the whole town of marvels and mud, with its maze of streets and its mass of lights’ so difficult to navigate that her ‘entrance into the open air had a foretaste of drowning’ (p. 198). Conrad’s London is persistently amphibious or aquatic, fluid not solid – an apt location for a novel that experiments with form by jumbling the order of its chapters, so that readers encounter Stevie blown up into fragments in a chapter before he helps his mother move house.

Conrad’s watery, seasick landscape, together with Doyle’s and Stevenson’s disorientating fogs, presents the capital as unsettlingly mobile and animate. That representation is refreshed in E M Forster’s Howards End (1910), similarly ambivalent about a city in flux. Naturally, London means different things to different characters: it is home, to the Schlegel sisters, of culture and humanity, but, for precarious clerk Leonard Bast, it remains a place of deprivation and desperation. A key scene sees Leonard visit the Schlegel sisters in hope of intellectual conversation: he soon discovers they’re more interested in his recent decision to spend a holiday walking overnight out of the city into the country surrounding it, from the gas lamps into the woods. Leonard’s ancestors, Forster tells us, were agricultural workers, and Leonard himself belongs more authentically to a rural past than an urban present. Moreover, Howards End itself, the ancestral family home which gives the book its title and its moral centre, is menaced by the encroaching city. ‘All the same, London’s creeping,’ remarks Helen to her sister Margaret in the final chapter, pointing out ‘eight or nine meadows’ surrounding Howards End, but menaced by ‘a red rust’.[7] Red rust, brown fog, a slimy aquarium: these borderline images are fascinated by apparent solidity dissolving into water or air.

For T S Eliot, such vagaries suggested an ‘Unreal City’:

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.[8]

At one level, The Waste Land (1922) describes a mundane phenomenon. Workers commuted by foot into the City of London in such numbers that rush-hour street etiquette required them to travel on the right and in the same direction as other pedestrians. Yet the commuting crowds, to which Eliot, a bank clerk, belonged, seemed both everyday and ‘unreal’. Anonymity and uniformity suggest an automatism verging on the uncanny – with resonances, too, of that other vast ‘crowd’ which had so recently marched to their deaths on the battlefields of the First World War. As for Conrad, Doyle and Stevenson, so for Eliot the city is a place of both excitement and estrangement.

Joyce’s Dublin: the centre of paralysis?

London’s vastness, its aura of being at the centre of the world, its economic and cultural importance, seems to produce anxiety, ambivalence and doubt. Paradoxically, being on the margins offered James Joyce greater scope to document the pleasures of city life. Joyce left the city of his birth, Dublin, at just 22 for a life of exile in cosmopolitan urban centres: Trieste, Zurich, Paris. His return to ‘dear dirty Dublin’ through his fiction initially imagines his home town as a place of ‘scrupulous meanness’, but later represents it with increasing affection as a place of imaginative and emotional opportunity.[9] In Dubliners, the city is dismissed as a second-rate place of paralysis, ‘wearing the mask of a capital’ in the story ‘After the Race’.[10]

In ‘The Dead’, Gabriel Conroy tells an anecdote about his grandfather’s horse Johnny, a beast so used to walking in a circle to drive a mill that he is unable to function when harnessed to a carriage:

And everything went on beautifully until Johnny came in sight of King Billy’s statue: and whether he fell in love with the horse King Billy sits on or whether he thought he was back again in the mill, anyhow he began to walk round the statue (p. 162).

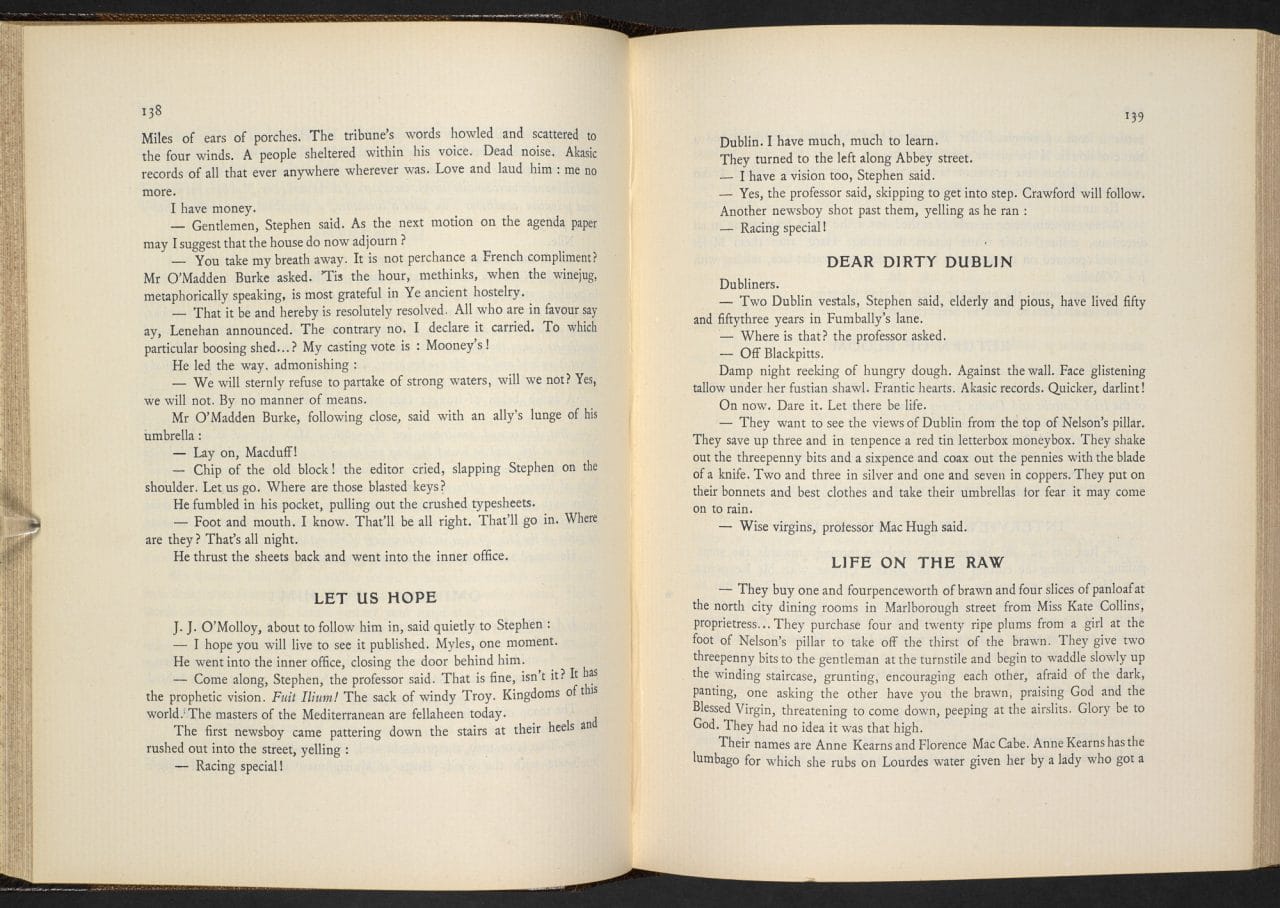

Gabriel’s tale inadvertently reveals his own fate, doomed to plod in a familiar provincial circle. Yet in Ulysses (1922), Joyce’s perspective has shifted, as he places a very different protagonist ‘IN THE HEART OF THE HIBERNIAN METROPOLIS’ (U 7: 1).

Leopold Bloom is a middle-aged Jewish advertising canvasser, who spends most of the day on which the novel is set, 16 June 1904, perambulating around his home city. Dublin is, occasionally, unwelcoming – Bloom is the target of anti-Semitic hostility while travelling to a funeral in the morning, and again while drinking in Barney Kiernan’s pub. But the city is more often a place of stimulation, opportunity and adventure. Many of Bloom’s serendipitous encounters look beyond Ireland to a wider world, such as when he reads a flyer urging him to invest in a Zionist scheme to plant orange and olive trees in Palestine, or when he takes a Turkish bath. But even those incidents closer to home – his erotic encounter with Gerty MacDowell on Sandymount Strand, his rescue of Stephen Dedalus from a street brawl in the ‘Circe’ episode, his visit to ask after the labouring Mina Purefoy in the maternity hospital, his furtive and anonymous correspondence with Martha Clifford – attest to the rich, generous magic of urban life. Bloom’s curious gaze makes him a particularly sympathetic version of Baudelaire’s flâneur. His wanderings allow him to observe urban phenomena: ‘a sugarsticky girl shovelling scoopfuls of creams for a christian brother’ (U 8: 2–3); advertisements for ‘That quack doctor for the clap’ (U 8: 95); the ‘Silk flash rich stockings white’ (U 5: 124) of an elegant woman mounting a carriage; or the ‘blind stripling … tapping the curbstone with his slender cane’ (U 8: 1075). Through Bloom’s compassionate eyes, Joyce gives a generous vision of the diversity of Dublin, a city full of life, colour and song.

Street-haunting for women: Woolf’s city pleasures

Joyce’s cosmopolitan marginality may have informed the shift in his writing from a sense of the city as the ‘centre of paralysis’ in Dubliners, to Ulysses‘s meticulous, celebratory recreation. Other experiences of marginality underscore Virginia Woolf‘s representations of city life, informed by her alertness to gender difference. Looking back to her sheltered Kensington girlhood of the 1880s in the early draft of The Years (1937), provisionally titled The Pargiters, she recalled ‘To be seen alone in Piccadilly was equivalent to walking up Abercorn Terrace in a dressing gown carrying a bath sponge’.[11] The city, Woolf underlines, is a very different place for women, hedged around with proprieties and dangers limiting their ability to emulate Baudelaire’s detached, anonymous flâneur. Accordingly, Woolf’s essay ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’ (1930) celebrates a wandering which was then still a novelty, beginning by framing a need to purchase a pencil as ‘an excuse for walking half across London between tea and dinner … the greatest pleasure of town life in winter’.[12] That exuberant sense of pleasure is also Clarissa Dalloway’s, deciding to ‘buy the flowers herself’ and so indulging in an unfettered stroll across Westminster: ‘What a lark! What a plunge!’[13]

In people’s eyes, in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.

This sense of jubilation is felt, too, by her daughter Elizabeth, who ‘most competently boarded the omnibus’ as it sails down Whitehall, ‘a pirate’, ‘reckless, unscrupulous, bearing down ruthlessly, circumventing dangerously, boldly snatching a passenger’ (p. 115). Mother, daughter and creator share an exhilaration arising from a freedom to feel at home in the street. That freedom was newly won for women, as the city becomes a landscape of opportunities.

However, in her dream-like depiction of consciousness, Woolf also represents the alienation and anxiety experienced in the modern urban space. The reader floats through the city while moving in and out of the characters’ minds; from the grieving mothers who have lost sons in the war to the shell-shocked, hallucinating Septimus Smith; and from the reminiscing Peter Walsh to the religious fanaticism of Miss Kilman – we even hear the internal monologue of the ‘battered old woman’ sitting outside Regent’s Park tube station. Mrs Dalloway may be set in a bustling city, but within this space each character is alone – and the novel sews together the inner thoughts of these isolated but intersecting individuals.

Ultimately though Woolf, like Baudelaire, weaves together the sense of estrangement and the sense of wonder, and shows her characters enjoying the possibilities that anonymity in the city affords. As Septimus thinks:

now that he was quite alone, condemned, deserted, as those who are about to die are alone, there was a luxury in it, an isolation full of sublimity; a freedom which the attached can never know.

脚注

- Charles Baudelaire, 'The Painter of Modern Life' in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. and ed. by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964)

- Charles Baudelaire, 'The Painter of Modern Life' in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. and ed. by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964)

- Charles Baudelaire, 'The Painter of Modern Life' in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. and ed. by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964)

- Robert Louis Stevenson, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and other stories, ed. by Roger Luckhurst (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 9.

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sign of Four (London: Spencer Blackett, 1890), pp. 39–40.

- Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent, ed. by John Lyon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 108.

- E M Forster, Howards End (London: A A Knopf, 1921), p. 388.

- In Finnegans Wake (1939), Joyce repeatedly riffs on the phrase, initially Lady Morgan's.

- Virginia Woolf, The Pargiters, ed. by Mitchell Leaska (New York: Harcourt, 1977).

- Virginia Woolf, 'Street Haunting' in The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (London: Harcourt Brace and Co, 1970), p. 20.

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, ed. by David Bradshaw (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 1.

Banner illustration by Matthew Richardson

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Katherine Mullin

Dr Katherine Mullin teaches Victorian and Modernist literature at the University of Leeds. She is the author of James Joyce, Sexuality and Social Purity (Cambridge University Press, 2003) and Working Girls: Fiction, Sexuality and Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2016).