Shakespeare’s London

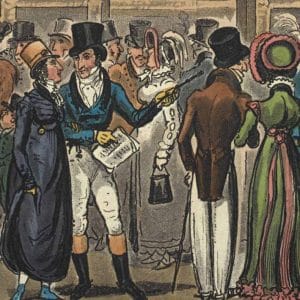

Early modern London was an expanding metropolis filled with diverse life, from courtiers, merchants and artisans to prostitutes, beggars and cutpurses. Here Professor Eric Rasmussen and Ian DeJong describe the city that shaped Shakespeare‘s imagination.

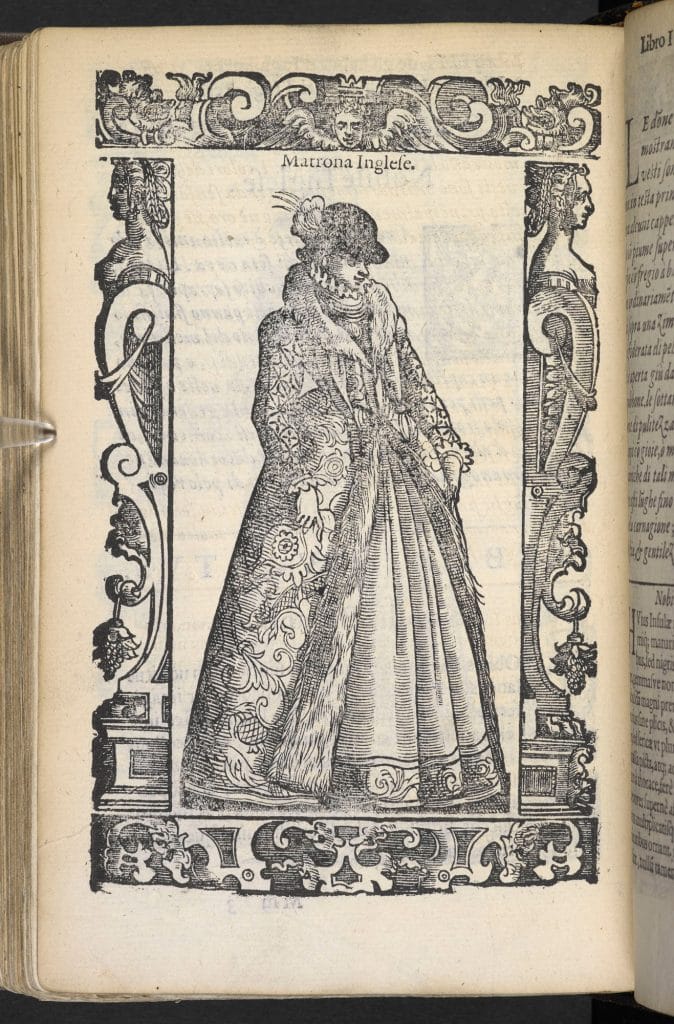

Shakespeare’s London was home to a cross-section of early modern English culture. Its populace of roughly 100,000 people included royalty, nobility, merchants, artisans, laborers, actors, beggars, thieves, and spies, as well as refugees from political and religious persecution on the continent. Drawn by England’s budding economy, merchants from the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and even further afield set up shop in London. As a result, Londoners would hear a variety of accents and languages as they strolled about the city – a chorus of voices from across Europe and from all walks of life.

The term ‘court’ referred both to these palaces and to the people who surrounded the monarch and travelled with her: a thousand or more servants, attendants, and courtiers. The court’s frequent movements appear to have been motivated less by the queen’s desire for a change of scenery than necessitated by a very basic practicality: those thousand bodies producing waste quickly overwhelmed the sanitation facilities in the palaces. Although flush toilets were invented by one of Elizabeth’s courtiers, John Harrington (the American slang-word for toilet, ‘john’, thus honours its inventor), no indoor plumbing was installed in any of the royal castles during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Thus, life at court could be luxurious, but it could also stink.

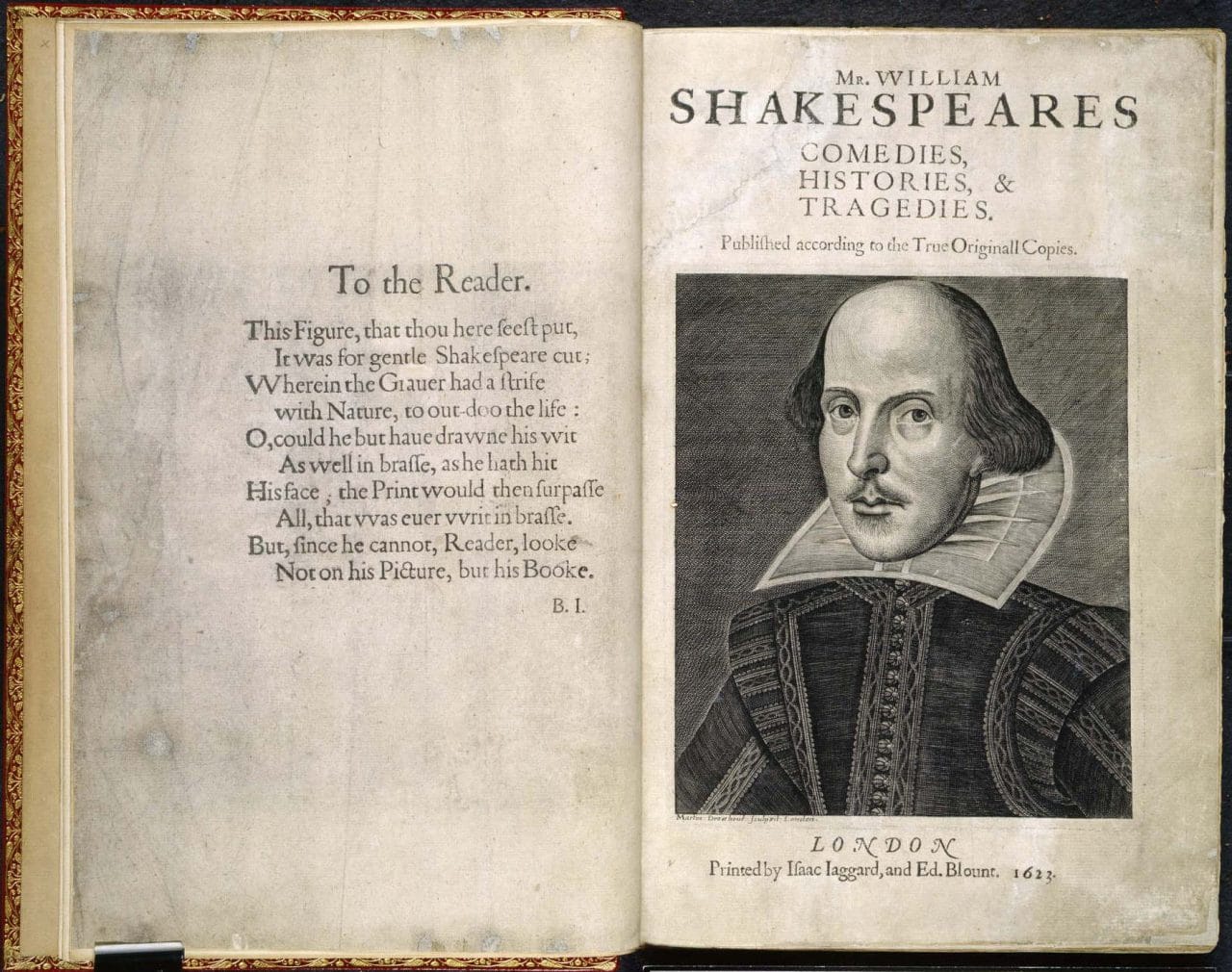

London in Shakespeare

When Shakespeare was active as an author, writing about London was en vogue. Ben Jonson and Thomas Dekker, among others, were famous for their ‘city comedies’. Although Shakespeare never contributed to this popular genre, London appears as a setting in several of the history plays, such as the two parts of Henry IV, where Falstaff’s home base, the Boar’s Head Inn, is located in Eastcheap. In a later historical period, but an earlier play, Richard III has his brother Clarence and his nephews murdered in the Tower of London. In the seldom-performed Henry VIII, the trial of Katherine takes place in Blackfriars. This name would have been well-known to early modern theatregoers, who would likely have attended plays in the indoor playhouse located in Blackfriars – just below the room in which Henry VIII places the trial.

Court and Royalty

Shakespeare’s London was bordered by royal sites: Westminster Abbey on the west, where every English monarch had been crowned since 1066; and the Tower on the east, where several had been imprisoned. Queen Elizabeth and King James had several palaces at their disposal in and around London: Whitehall (the largest palace in all of Europe), Hampton Court, Greenwich, Richmond, Westminster, St. James, and Windsor Castle. These were magnificent structures inside and out, and afforded the royals the greatest comforts to be found in London, such as fireplaces in nearly every room, along with oak paneled walls hung with tapestries, providing warmth and insulation. Queen Elizabeth would move from one palace to another during the calendar year, usually spending Christmas at Whitehall, New Year’s at Richmond, and then Easter in Windsor.

Making a Living in London

Though royalty, the court, and aristocrats may have been the most visible members of London society, a large portion of early modern London’s population worked for a living. The city’s tradesmen, artificers, merchants and manufacturers may claim much of the credit for London’s growth before and during Shakespeare’s lifetime.

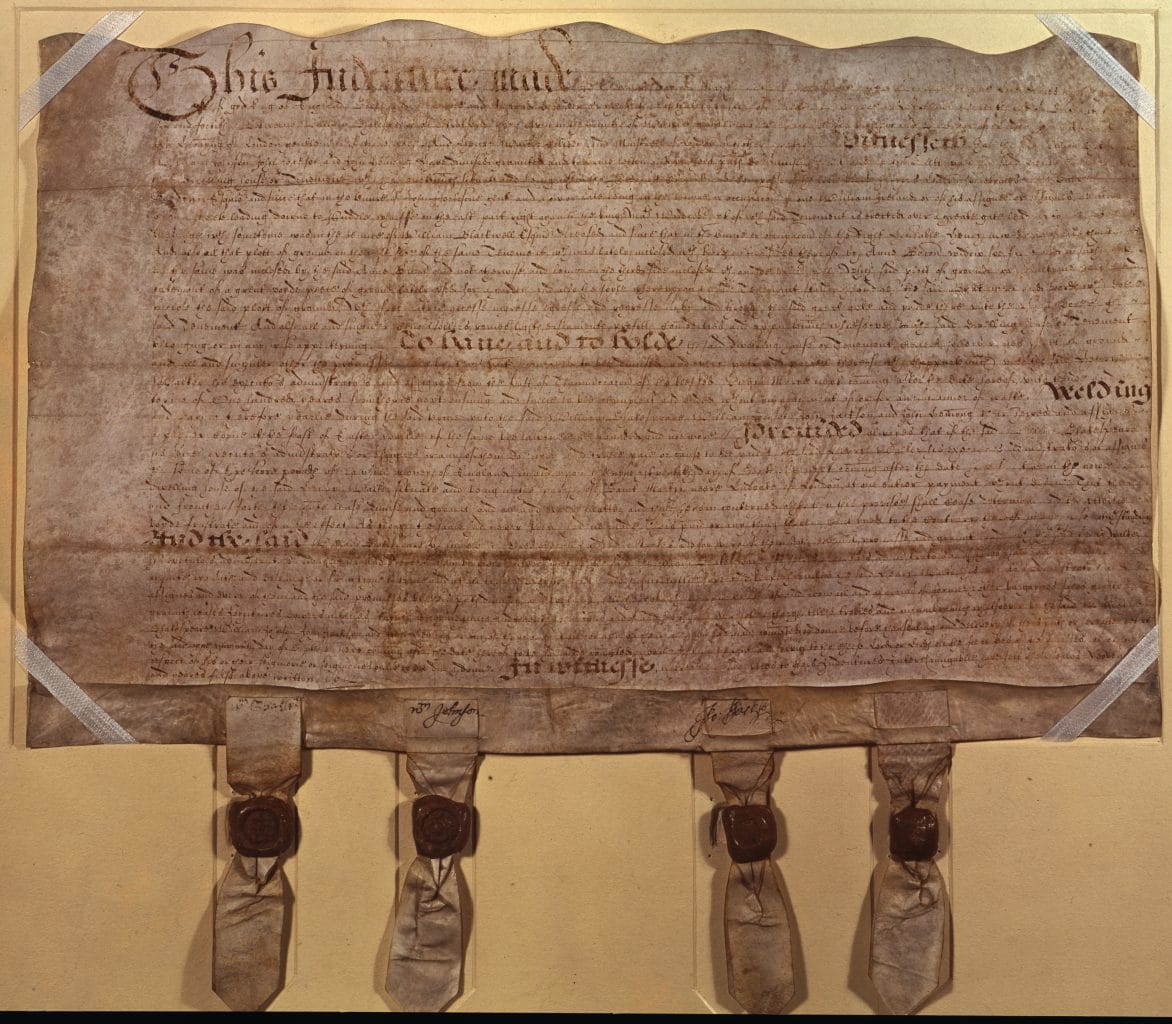

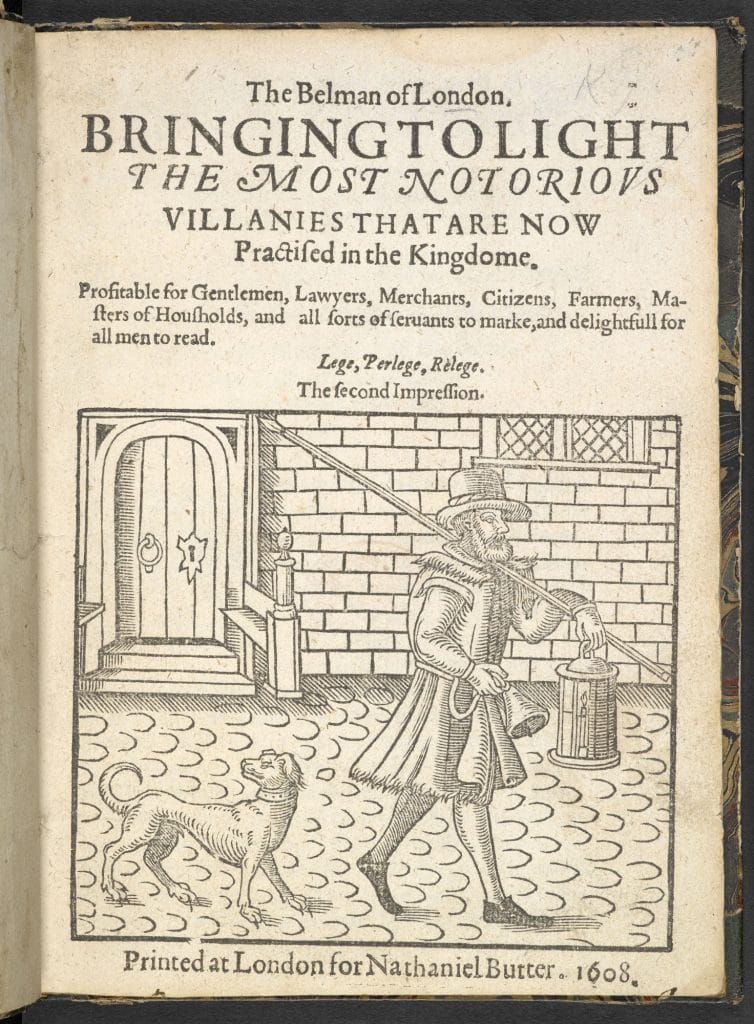

The printed word was among the commodities actively produced and sold in Shakespeare’s London. Technological advances made it possible to churn out pamphlets, sermons, plays, poems, proclamations, diatribes, and jeremiads at a tremendous rate. Booksellers took these varied materials and made them available to patrons from across London – nobility, wealthy bourgeois, artisans and even the literate poor.

Although anyone who had some level of trade, craft, or artisanal skill could make a life in London, one obstacle they faced was the guild system – a holdover from a medieval mode of organizing and regulating labour. Guilds had provided valuable social and commercial structure, establishing hierarchies (from apprentice to master) based on experience and skill level. They also provided a means of excluding undesirable members. If for some reason a London tradesman fell into disfavour in a guild, he could be censured or even expelled. Such exclusion could have drastic consequences, plunging the hapless tradesman into poverty – which, in London, was a serious predicament. Early modern London was a bad place to be poor.

Poverty and the Plague

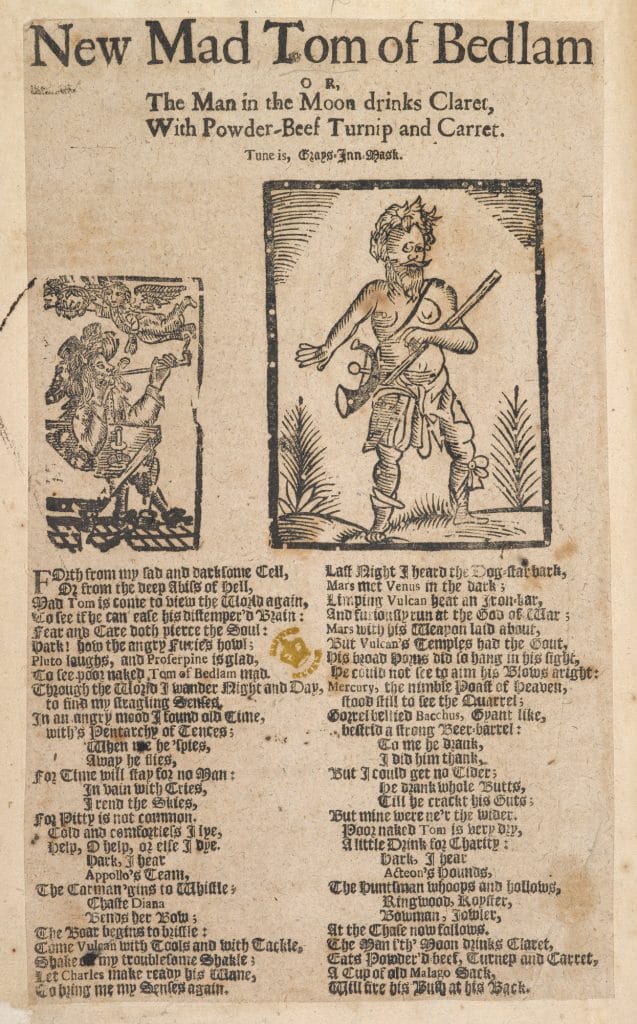

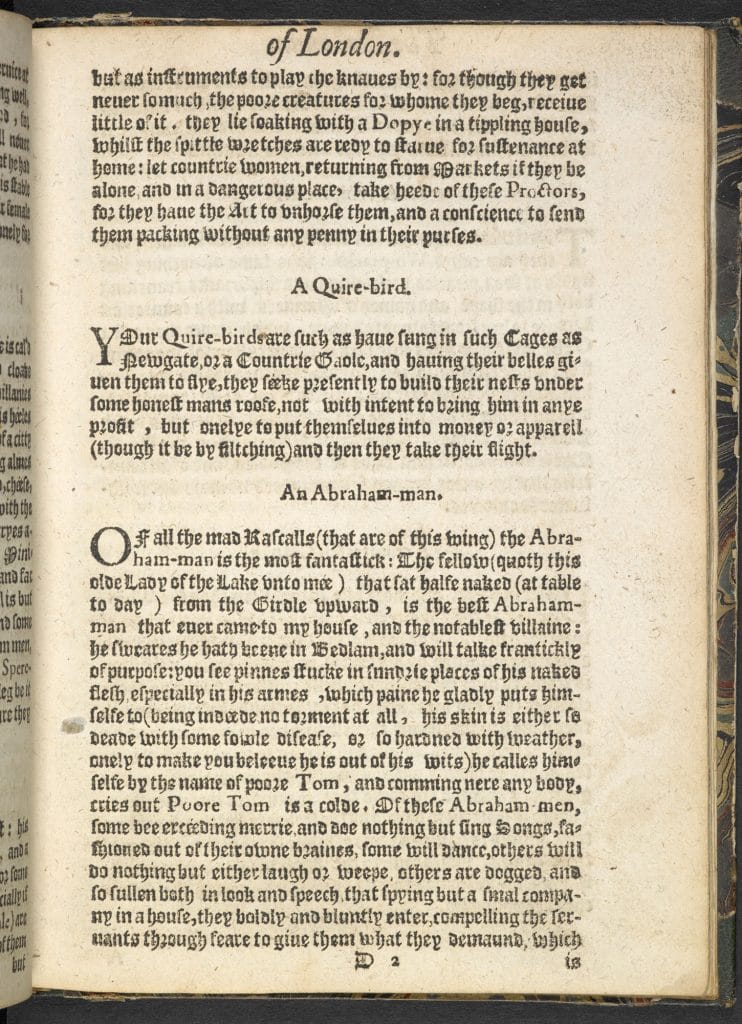

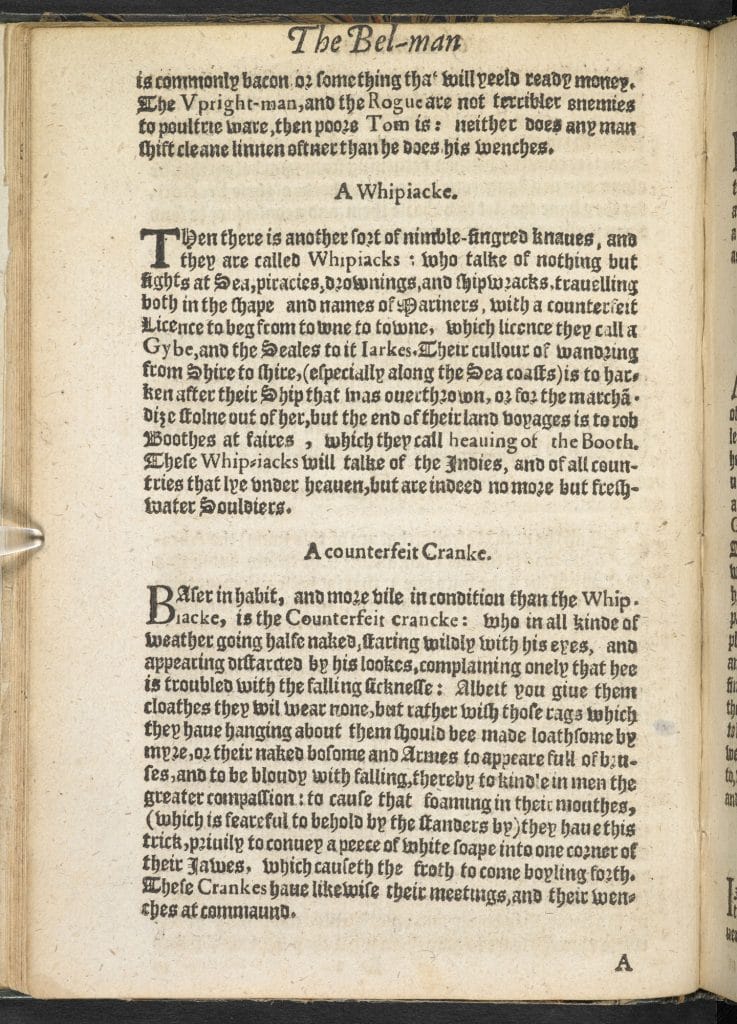

In Shakespeare’s time, the poor had little hope of escaping hunger, cold, damp, disease, and exposure. Beggars flooded the streets. Some were veterans – often maimed or disfigured – of the ongoing, undeclared war between Spain and England. Others were freemen who had been expelled from guilds. Still others had come up from the country perhaps hoping to find work, or trying to avoid family entanglements, or running from the law.

Because the poor were largely illiterate, they left little record of their existence. What we know about them comes mainly from government documents, such as the first legislation providing relief of the poor and the laws regarding vagabondage. John Stow’s Survey of London (1598) recounts in great detail various royal initiatives to designate refuges for the ‘leprous’ in London’s population, ‘for avoiding the danger of infection’. By 1601, poverty was so widespread that Elizabeth handed down ‘An Act for the Relief of the Poor’, which mandated local, community responses to indigent populations. The government wished to provide for the poor not necessarily out of any sense of charity or human kindness, but rather because of the plague.

Well after the period of the Black Death, the great pandemic of the 14th century, the bubonic plague continued to wax and wane in Europe. London, with its rapidly ballooning population and constant flow of new arrivals, was especially vulnerable. Despite the best attempts of the government, the plague remained a part of daily life in London. The theatres, considered to be hotbeds for contagion, were repeatedly closed throughout Shakespeare’s career.

In the minds of London’s more prosperous citizens, fear of the plague was linked in part to distaste for the poor, the disabled, the homeless. Besides condemning them as disease-ridden, the upper and middle classes often demonized London’s less fortunate as criminal Yet it is true that in London, as in any great city, there were many who broke the law, whether reluctantly or eagerly. Shouldering through a rough crowd in the city, Shakespeare might have passed by thieves in pillories; small boys might have brushed past him, trying to pick his pockets. Cutpurses might have tracked the well-dressed Shakespeare, testing the edges of the knives they used to slice the strings that attached purses to clothing. Prostitutes, brightly painted with lead-based makeup, might have leaned out of casements, calling to potential customers. Shakespeare might have seen, and steered clear of, muscled, scarred bruisers, sullen veterans of the war with Spain, spoiling for a fight with whoever crossed them.

The Great River

In addition to documenting the plight of the poor, Stow’s Survey (in its 1603 edition) also provided a vivid depiction of the river Thames, the great contributor to London’s emergence as Europe’s largest, most important city. By way of the river, Stow wrote,

all kind of merchandise be easily conveyed to London, the principal store house, and staple of all commodities within this realm, so that omitting to speak of great ships, and other vessels of burden, there pertaineth to the cities of London, Westminster, and borough of Southwark, above the number as is supposed of 2000 wherries and other small boats, whereby 3000 poor men at the least be set on work and maintained.

Given how essential the Thames was to the life of the city, it is perhaps surprising that Londoners did not treat it very well. By the early modern period, it was a receptacle for industrial and human waste. Audiences at the Globe Theatre must have prayed for cool weather, to keep down the stink of the river oozing past just outside. Clogged with filth as it was, the Thames must also have been a major carrier of disease. And the severed heads of executed traitors placed on poles along London Bridge surely added a macabre element to the already fetid environment.

The Romans had chosen the location of London, of course, because it was the first point that the river was narrow enough to erect a bridge across it using the technology of the day, and London Bridge had been for centuries a thriving center of commerce. In Shakespeare’s time it was lined with over a hundred buildings, many with shops on the ground floor and houses above, stalls, and even the four-story palace ‘Nonesuch House’ – so named because there was ‘none such like it’ in all of Europe – with a plaque on its south side facing the river that read ‘the Time and Tide stay for no man’. One of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, Michael Drayton, nicely sums up London pride in their Thames: ‘With that most costly Bridge that doth him most renown, / By which he clearly puts all other rivers down’.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Eric Rasmussen and Ian DeJong

Eric Rasmussen, Foundation Professor and Chair of English at the University of Nevada, is co-editor of the award-winning Royal Shakespeare Company’s edition of William Shakespeare: The Complete Works and William Shakespeare and Others: Collaborative Plays. Ian DeJong is a doctoral student at the University of Nevada. His scholarship centers around the cultural construction of Shakespeare. His work has appeared in Shakespeare Quarterly.