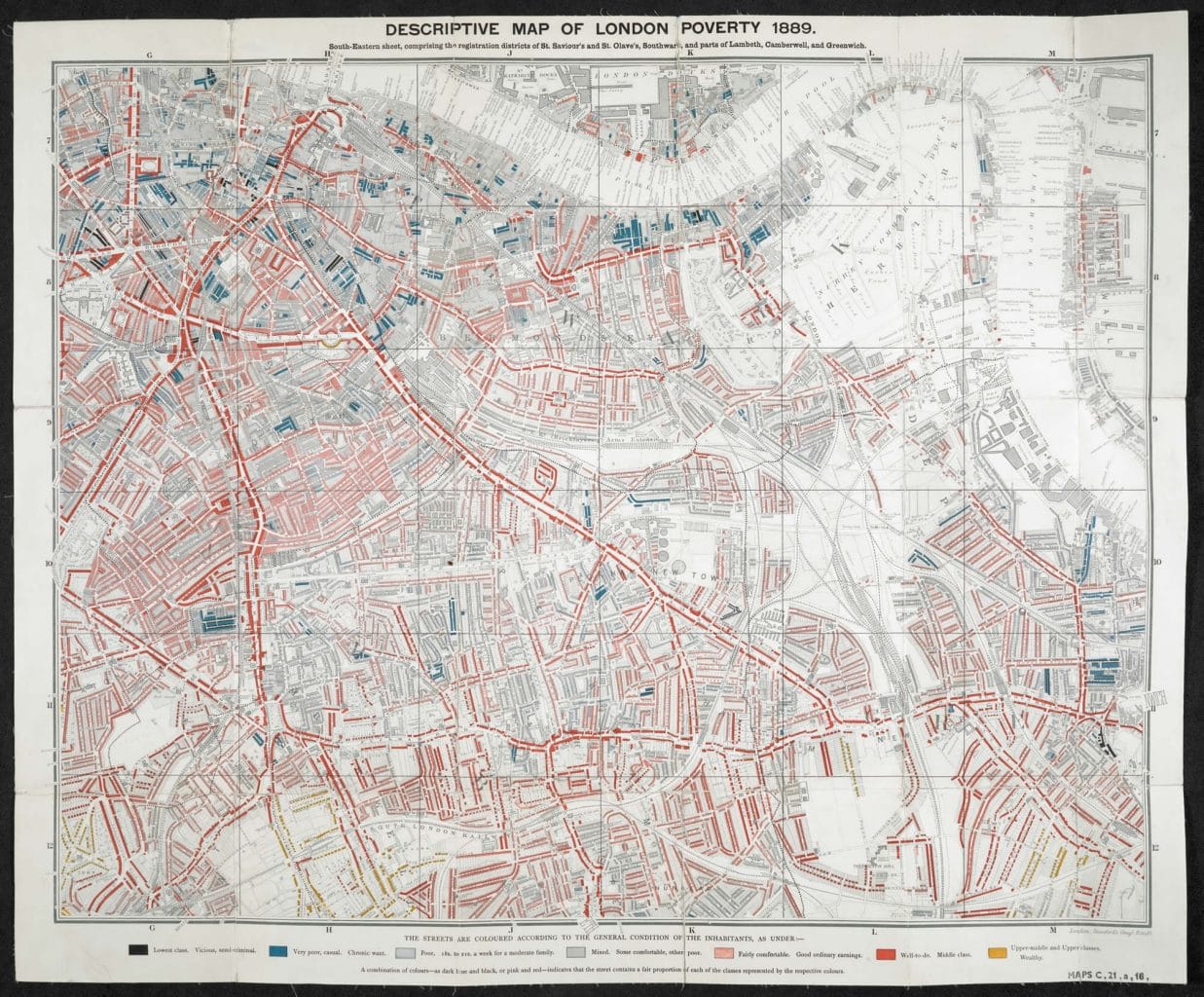

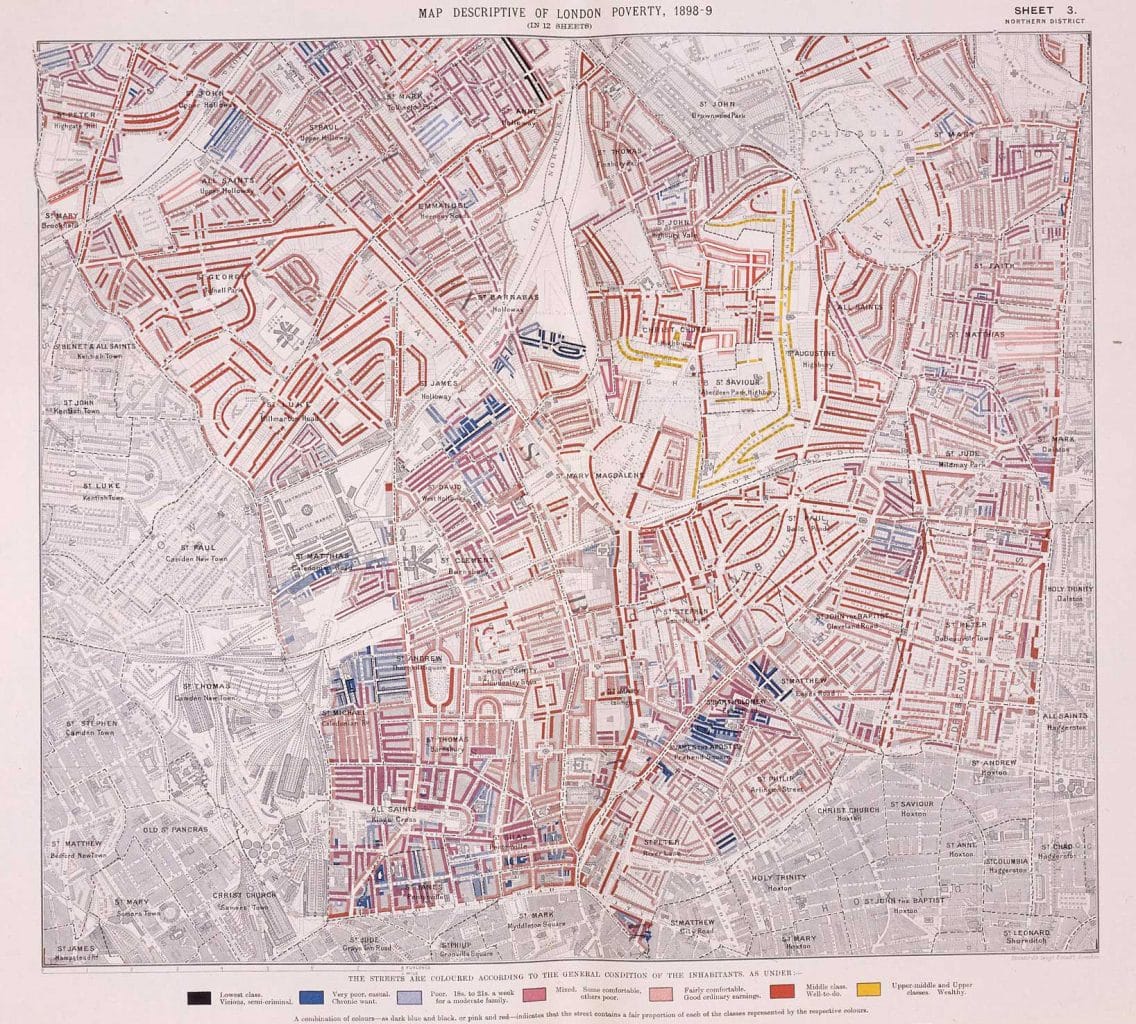

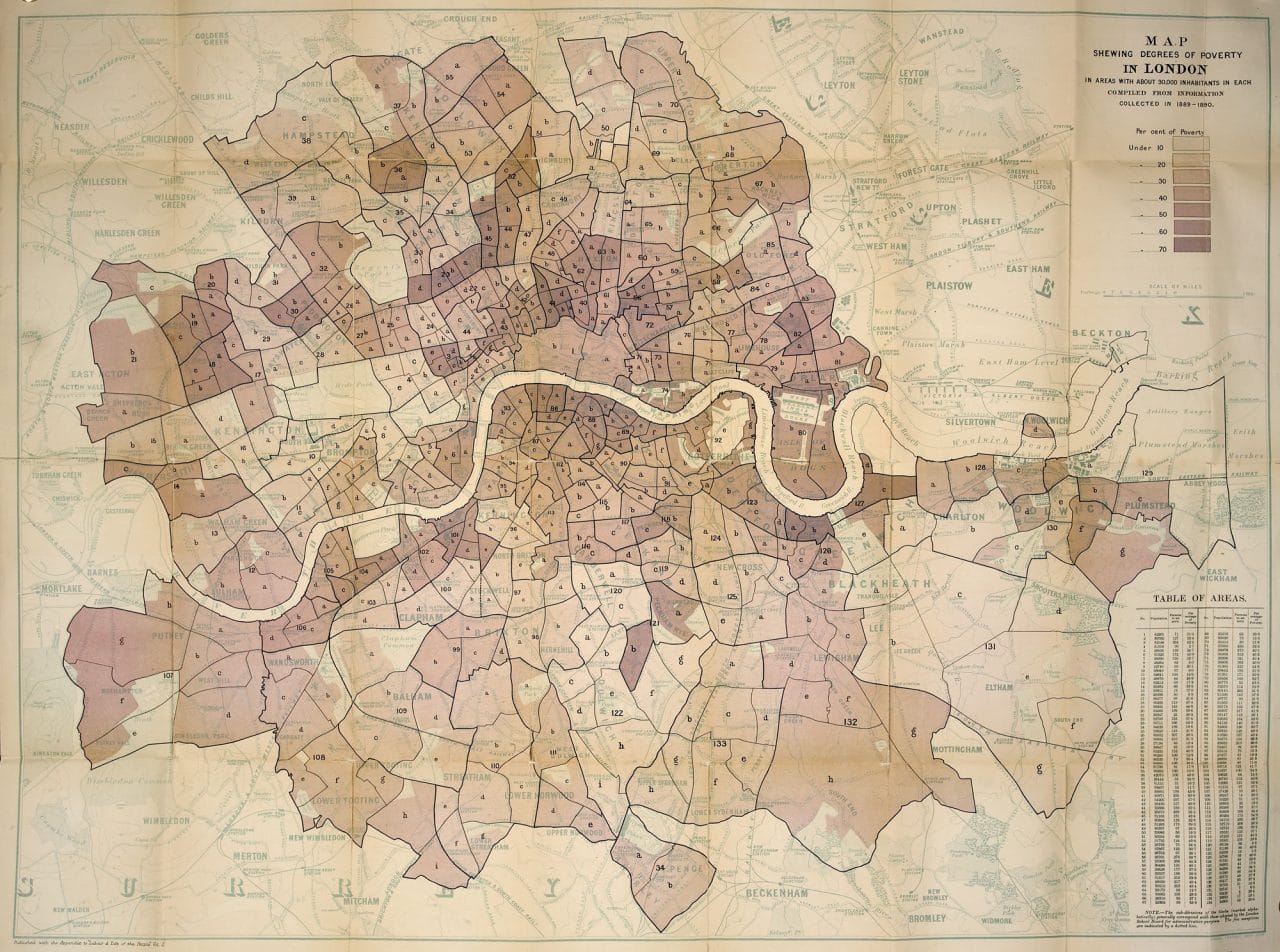

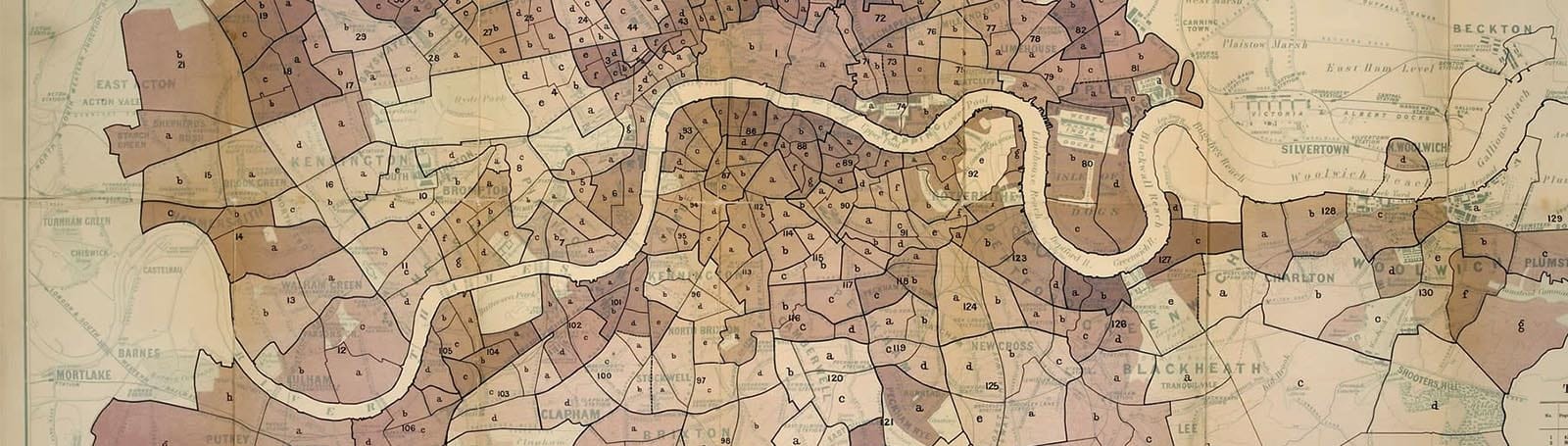

Charles Booth’s poverty map of London

Victorian businessman Charles Booth set out to see if poverty levels were exaggerated – and found they were worse. His map shows the patchwork nature of the capital: poor and rich live side by side, much like today. Booth’s work helped establish the old age pension, first paid on 1 Jan 1909.

Who was Booth and why did he make this map?

During the 1800s, a great proportion of Londoners lived in terrible poverty. Victorian cities were overcrowded, filthy and bleak. Charles Booth was a successful businessman who thought social reformers had exaggerated London’s poverty levels, said to be about a quarter. In 1886, he decided to find out the truth. As part of his research Booth lived with working-class families for several weeks at a time. It revealed the level of want was even worse than generally thought: as many as one third of Londoners lived in poverty.

He took into account a wide variety of subjects including working conditions, education, wage levels, workhouses, religion, and police. He wrote of the many happy children he met who were, he wrote, free from the swarms of servants, nurses and governesses that overshadowed the lives of wealthier children. However, he recognised that for poor families disease, hunger and even death were an ever-present danger, and that many lived in a constant state of fear.

Booth’s study was published in 17 volumes under the title Life and Labour of the People in London. This map was included in the published work. Using a colour code, the map represents varying levels of poverty in different districts across London: for example, dark blue stands for ‘Very poor. Casual, chronic want’, while black stands for ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi criminal.’

What options did the poor have?

For many centuries there had been little or no safety net against poverty and illness. There was certainly no right to it. The industrial age saw extensive poverty amongst a rapidly expanding urban population. As moral and political pressure for reform built across society, the government’s role in providing a safety net gradually increased.

Workhouses began to appear from the mid-1600s, and at first were seen as beneficial. However, some parishes and employers used them as cheap labour. The Corn Laws, which kept the price of corn high to protect landowners whilst taxing the import of foreign corn, increased poverty.

Matters came to a head in 1830 with the Swing riots, named after Captain Swing, the revolt’s mysterious figurehead. Like the Luddites in the towns, agricultural labourers found their livelihood diminished by mechanisation and land grabs. Riots spread from Kent, the largest popular uprising since the Peasants’ Revolt.

Meanwhile, the cost of administering poor relief had risen more than ten times since the 1750s. The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act set up a Poor Law Commission to administer the system through unions spread across the parishes. This did not solve the problem of poverty, but simply contained the genuinely poor. Some relief was still paid, but the emphasis shifted to the workhouse.

What were workhouses like?

To discourage idlers, the regime was stern and unwelcoming. Able-bodied paupers were set to work crushing bones for fertiliser, breaking rocks or picking oakum. Sexes were segregated and families split up. Food was rationed and men and children resorted to sucking the marrow from the bones they crushed.

Such abuses led the government to take more control. The Poor Law Commission was replaced by the Poor Law Board in 1847. Although conditions improved, workhouses remained an ever-present threat and were not abolished until 1930, and even then many lingered on for years.

What did Booth’s work achieve?

Booth’s work was instrumental in establishing the old age pension, an idea which had been around since Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man in 1791.

Following years of campaigning, Liberal Chancellor Herbert Asquith managed to juggle the Budget to free up funds to pay for a free state weekly payment to the old. As Prime Minister he saw it through Parliament in August 1908.

The first pensions were paid on 1 Jan 1909 (2 January in Scotland). At a thanksgiving service held on 3 Jan Frederick Rogers, secretary of the NCOL, acknowledged Booth’s considerable work and added: “Pensions were given to the aged, not as a charity, but as a right.” Every effort had been made to ensure they did not carry the stigma of poor relief. Take-up in the first week was over 50 per cent and continued to grow.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.