Oliver Twist and the workhouse

The hardships of the Victorian workhouse led Oliver Twist utter the famous phrase ‘Please Sir, I want some more’. Here Ruth Richardson explores Dickens’s own experiences of poverty and the social and political context in which he was writing.

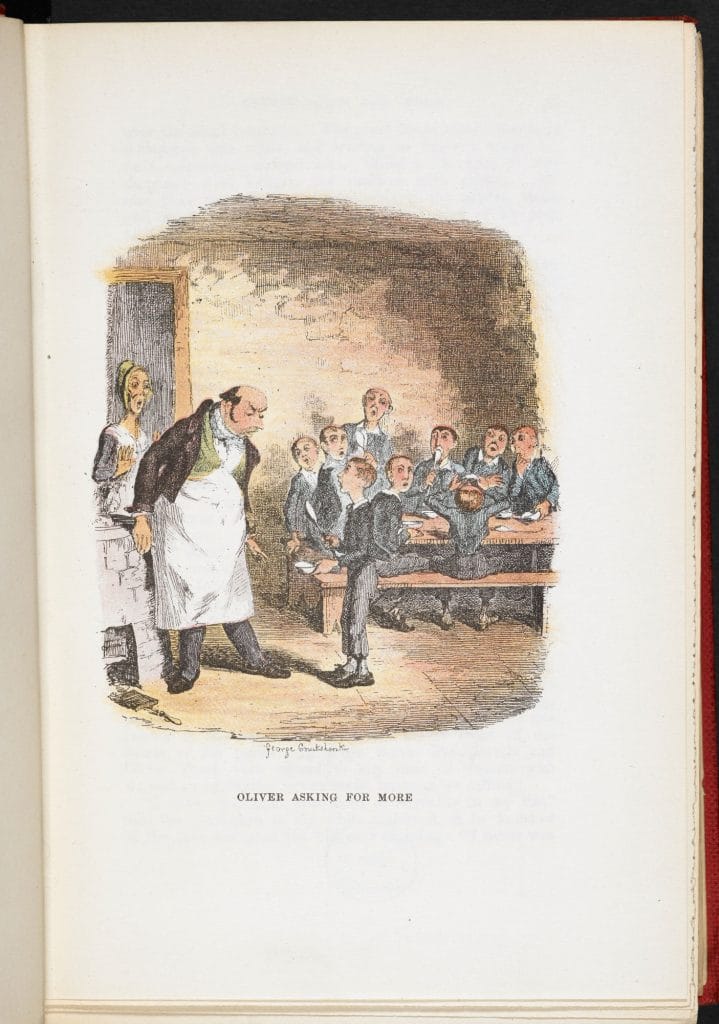

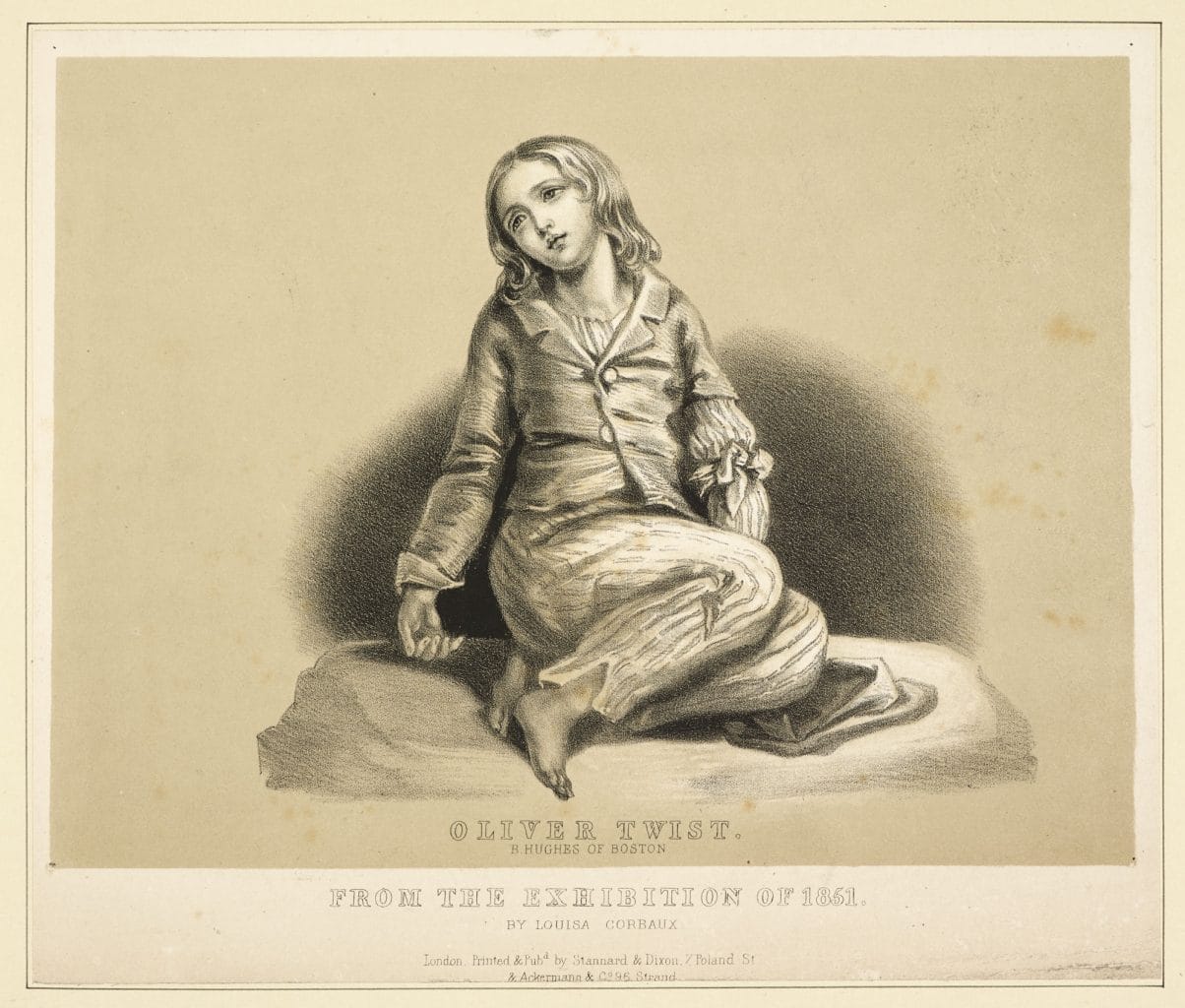

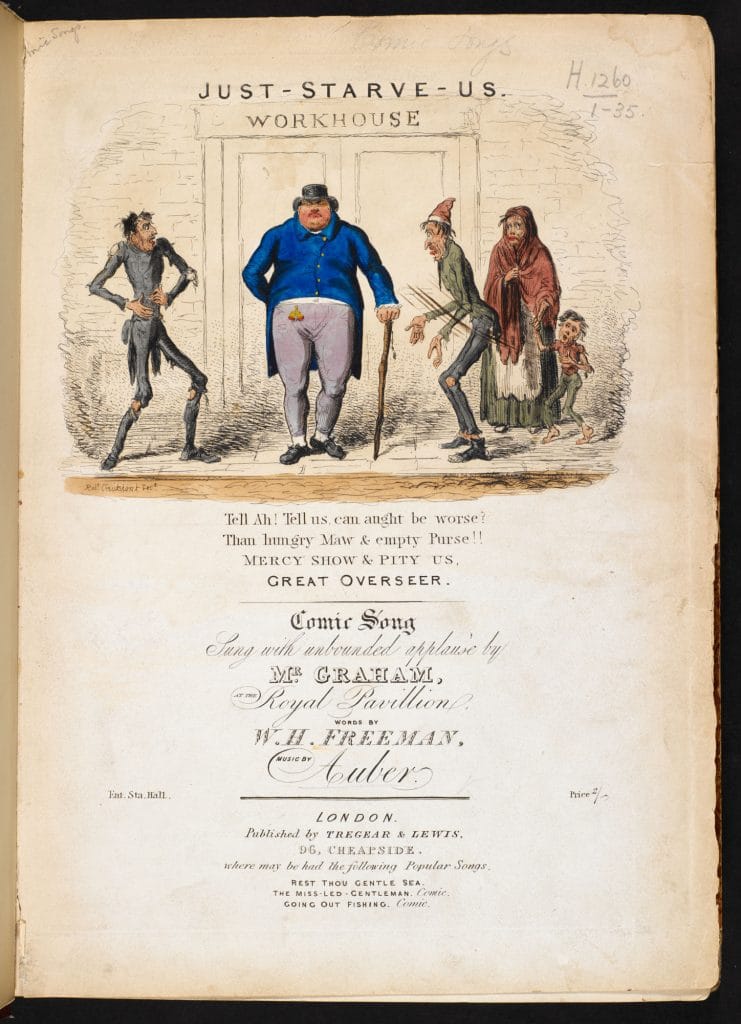

Most people nowadays know about the Poor Law and its workhouses from Oliver Twist – whether from the book, film or the musical. The image of the skinny neglected little boy asking for more has become a classic. For Charles Dickens, writing a novel about the Poor Law was a thoughtful intervention in a contemporary national debate. You can hear in his tone of voice – occasionally heavy with satire or irony – that he regarded the Poor Law as profoundly un-Christian.

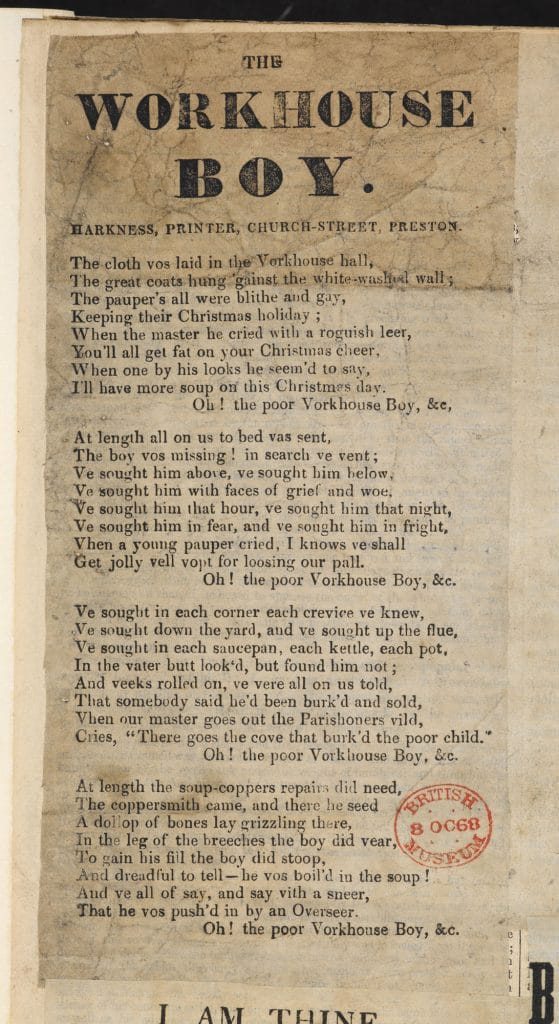

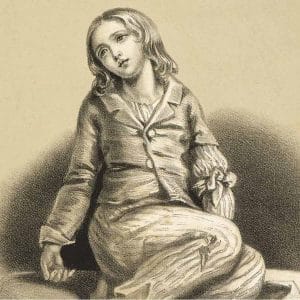

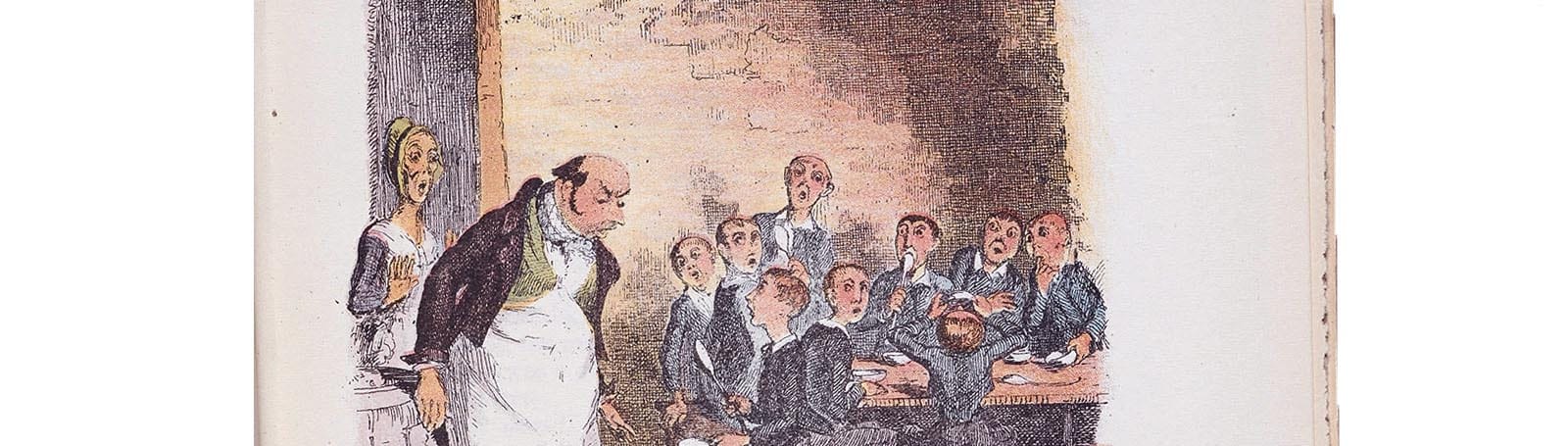

Dickens intended Oliver Twist, first published in monthly instalments between February 1837 and April 1839, to show the system’s treatment of an innocent child born and raised in the workhouse system, where no ‘fault’ could be ascribed to the child. He shows the boys neglected, ill-treated, and experiencing hunger so bad that one child threatens to eat one of the others if he isn’t better fed. Oliver has the temerity to ask for more food only because the hungry boys had cast lots to decide who would have to do it – and he had drawn the short straw. In the famous illustration by George Cruikshank, the poor orphan Oliver stands utterly alone – with the fearful threat of cannibalism right behind him, and facing him, the bully of a workhouse master preparing to unleash his powers of retribution. The pauper woman helper in the background recognises the danger of what Oliver has done, throwing up her hands in horror.

The description of Oliver’s punishments for his request – a natural entreaty from a growing boy – occupies quite a chunk of the following chapter. The sheer brutality of the system is exposed. Oliver is maligned, threatened with being hanged, drawn and quartered; he is starved, caned, and flogged before an audience of paupers, solitarily confined in the dark for days, kicked and cursed, hauled up before a magistrate and sent to work in an undertaker’s, fed on animal scraps, taunted, and forced to sleep with coffins.

The New Poor Law

Dickens was disgusted by Parliament. Before becoming a successful novelist, he had worked as parliamentary reporter. He had watched politicians at very close quarters, rapidly taking down their speeches word for word in shorthand notes, and then transcribing them for daily newspaper reports. He had listened carefully to many debates, and he was sickened by the attitudes MPs expressed towards their fellow human-beings. When Dickens planned and penned Oliver Twist, new legislation was just beginning to be implemented across the country.

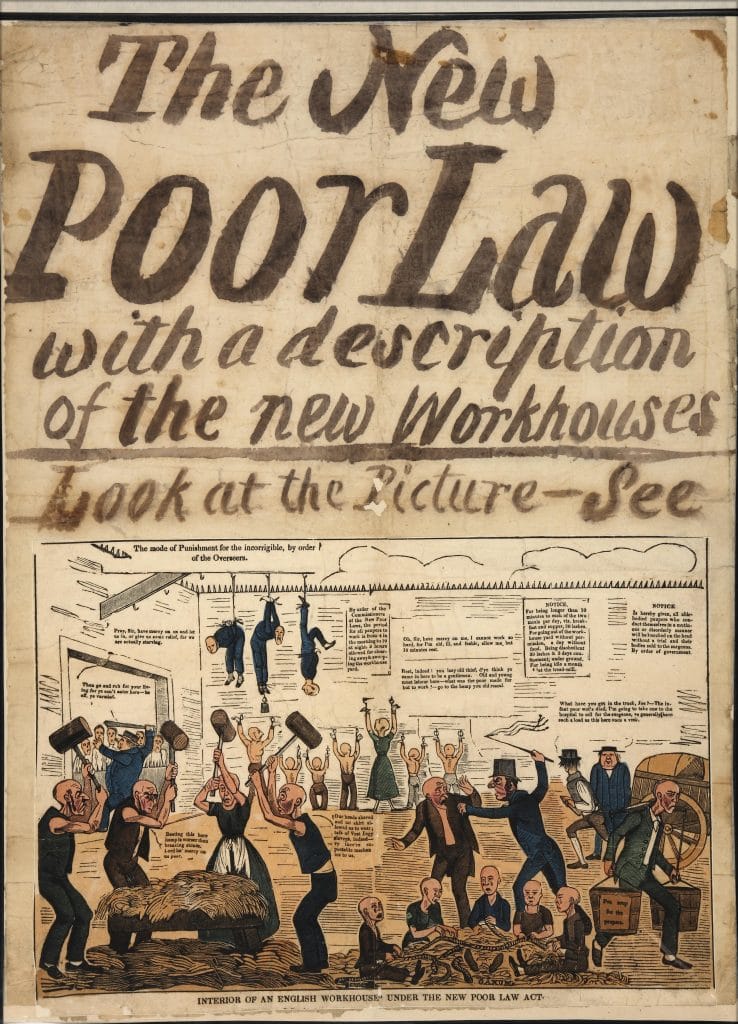

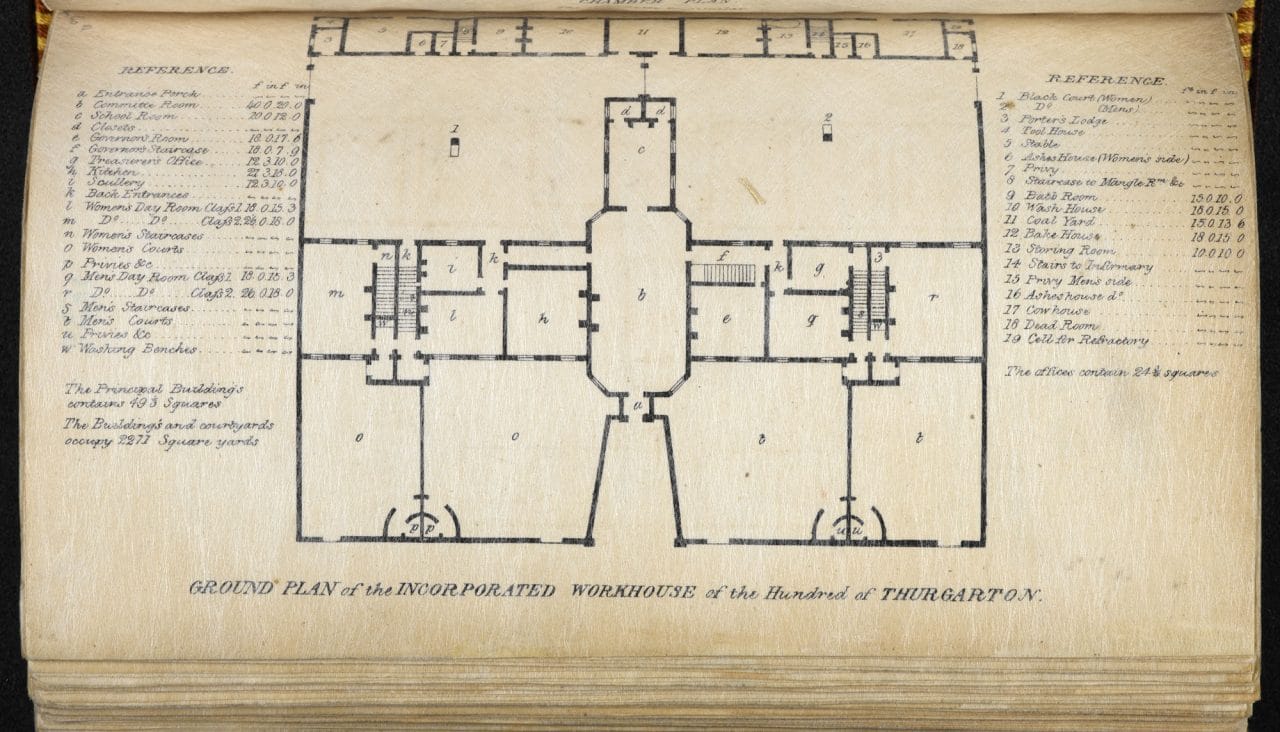

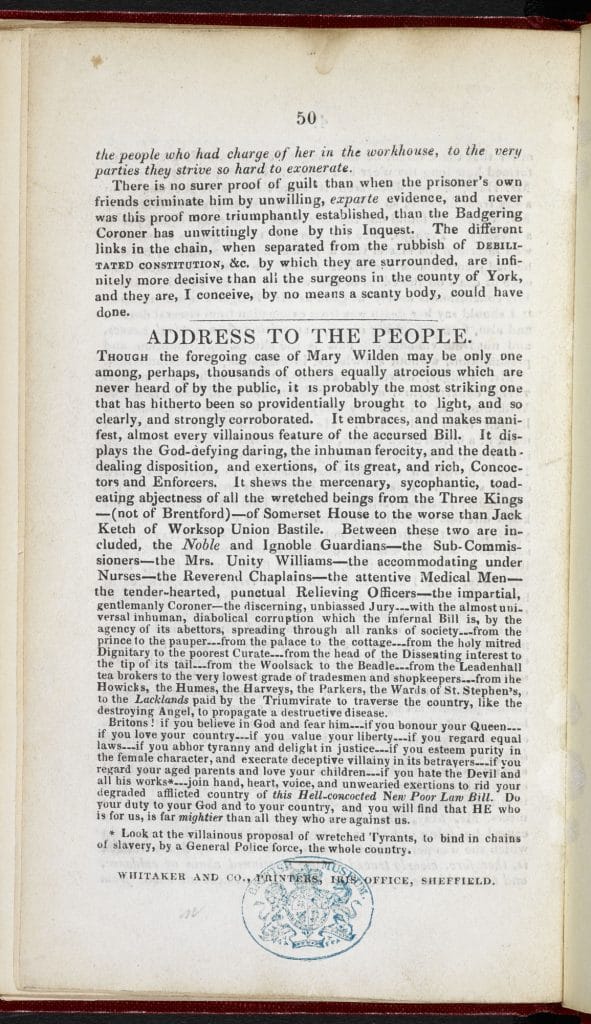

The Poor Law (Amendment) Act of 1834, otherwise known as the ‘New’ Poor Law, established the workhouse system. Instead of providing a refuge for the elderly, sick and poor, and instead of providing food or clothing in exchange for work in times of high unemployment, workhouses were to become a sort of prison system. The government’s intention was to slash expenditure on poverty by setting up a cruelly deterrent regime. The old parish poorhouses and almshouses were to be completely changed, no cash support whatever would henceforth be given out – whatever the hardship or the season – and the old gifts in kind (food, shoes, blankets) which could help a family survive together, were now disallowed. The only option would be hard work, forced labour, and only inside the workhouse (which meant entering there to live, full time) in exchange for a thin subsistence. Homes were broken up, belongings sold, families separated.

Groups of parishes – called Poor Law Unions – were formed under the new system, and a network of workhouses was established across the country. They were run by ‘Guardians’ who were usually local business people. The regime inside these places was deliberately intended to deter everyone but the most desperate. Children were separated and sent away, heads were shaved, clothes boiled, uniforms issued. Although centrally-controlled through the Poor Law Board, each workhouse was administered locally. Dickens shows that the administration was run by self-satisfied and heartless men: the ‘man in the white waistcoat’ personifies the smug viciousness of the guardians in Oliver Twist’s workhouse (ch. 2).[1] This is likely to have been something Dickens knew about: he had probably reported on such matters in London, and many accurate details in Oliver Twist show that Dickens did a lot of research before he wrote the story. It is true that the workhouse system was patchy: in some places – especially in parts of the North of England – more charitable notions among the ‘guardians’ of the poor meant that management could be kinder. In general, though, the system was harsh and austere. The poor – even if sick, old or dying – were treated punitively, as if their predicament was entirely of their own making, and they were deserving of punishment. This was at a time when there was no National Health Service to help the sick get well, no pension scheme to help the elderly remain at home, no unemployment pay for people with no work, no social services at all for those in need.

The workhouse system was hated, and people did everything they could to avoid becoming subject to it, so those who ended up there were either the most vulnerable, or the most hardened and brazen. Sadly, these groups were often housed in the same wards. Charitable hospitals generally refused access to those suffering from chronic (incurable) conditions, dying patients, and paupers. So workhouse inmates were often people whose medical conditions were regarded as hopeless at the time, and whose social status debarred them from other kinds of help. The Victorian Poor Law system effectively warehoused people the Nazis would have liked to liquidate: the sick, elderly and infirm, people who were chronically ill or incurable, physically deformed, diseased, maimed, lunatic, demented or mentally handicapped.

Dickens’s personal experience

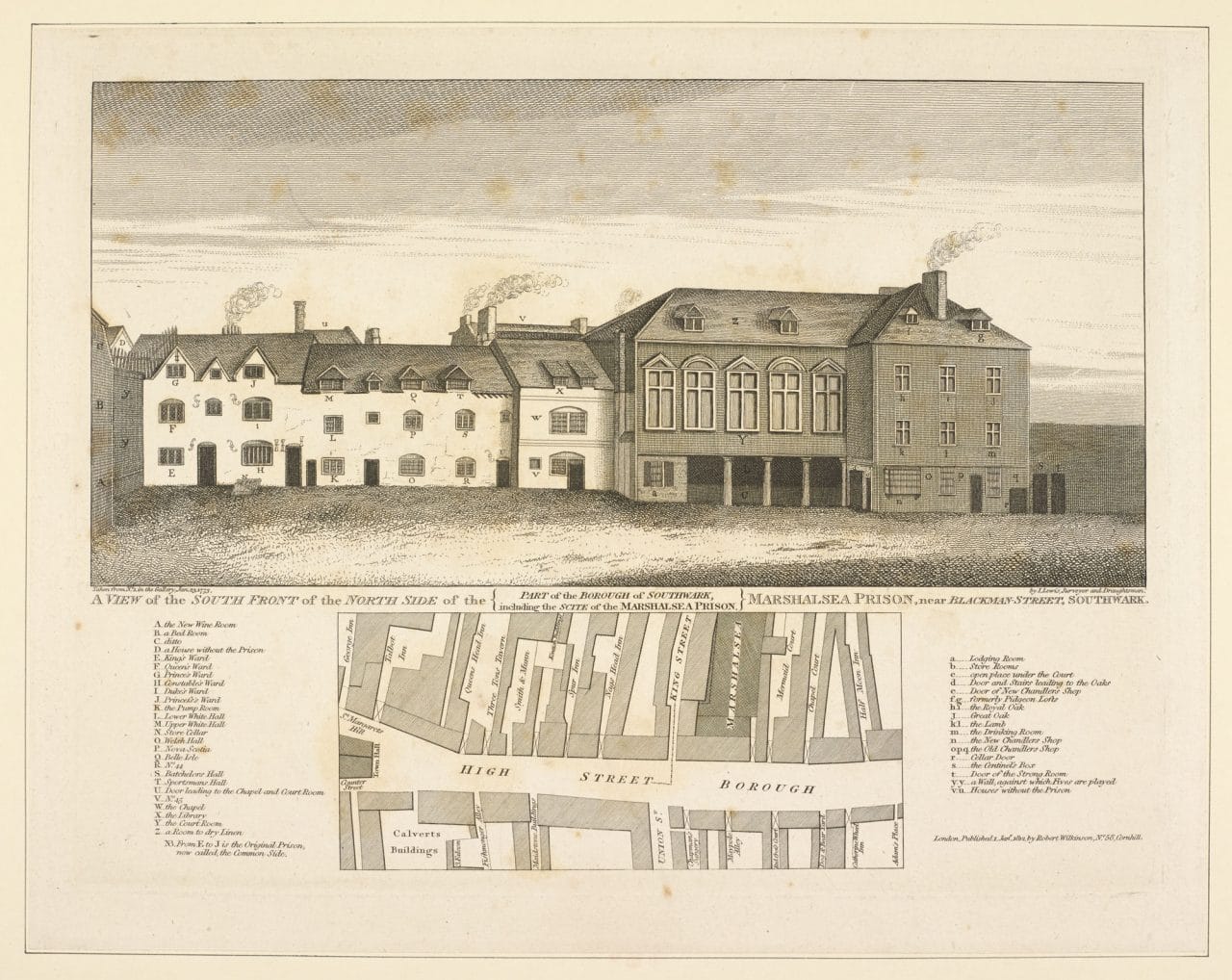

Dickens was only 25 when he started writing Oliver Twist in the winter of 1836–37. Because of his own life-experience he understood that accidents of birth or circumstance could make ordinary individuals vulnerable to desperation, hunger, cruelty and crime. His secret (which was only revealed after his death) was that when he was a child, his own family had been imprisoned in a debtors’ prison. However terrible that experience was for him – and it marked him for life – he knew it was actually preferable to being incarcerated in a workhouse. In a debtors’ prison, the family was at least allowed to remain together.

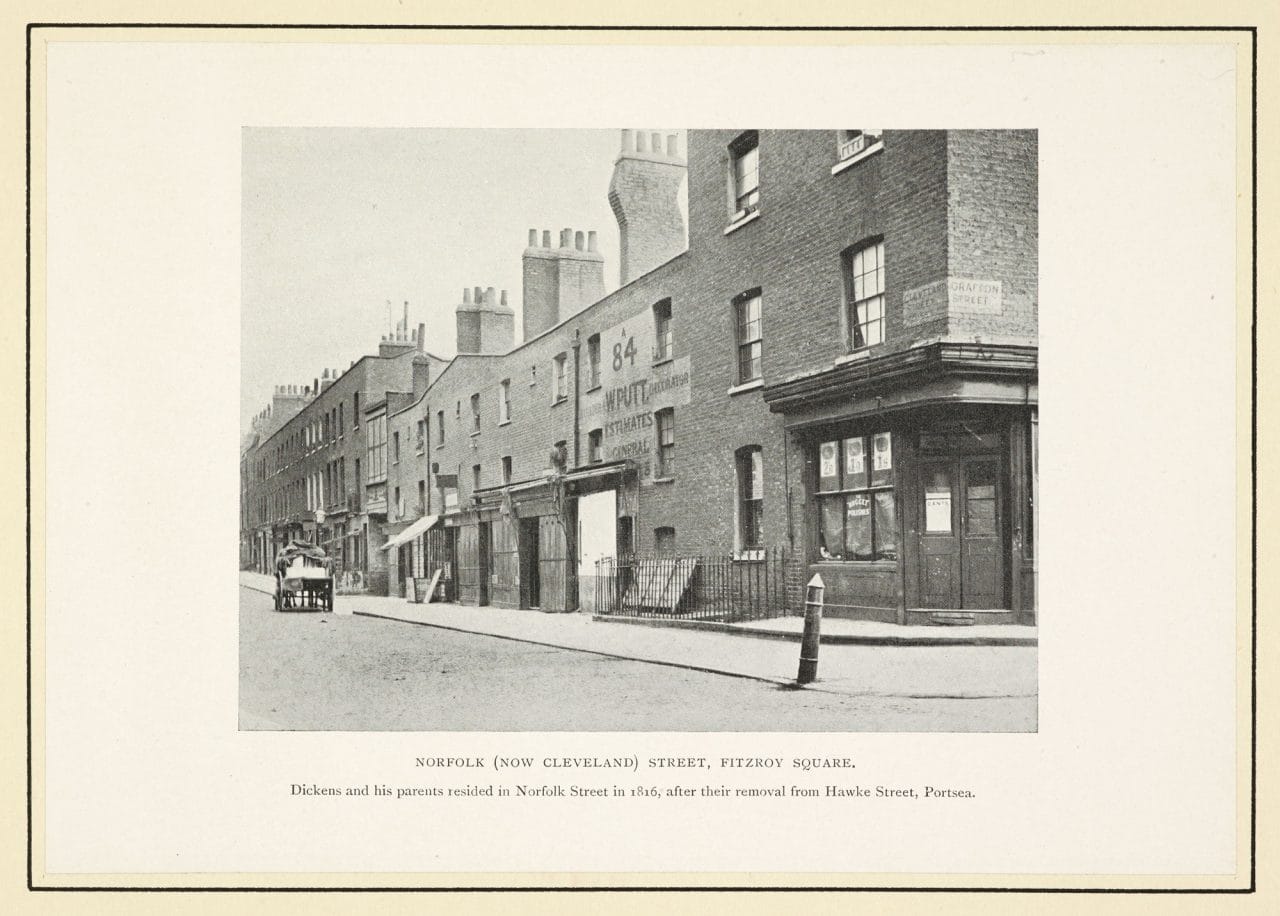

The Dickens family had also twice lived only doors from a major London workhouse (the Cleveland Street Workhouse), so they had most likely seen and heard of many sorrowful things. The family’s lodgings were above a food shop, and it is quite possible that young Dickens felt deeply sensitive about the suffering he knew was going on inside the institution close by. As an adult, Dickens knew that he himself had been fortunate to avoid a fate like Oliver Twist’s.

The diet at the Cleveland Street Workhouse

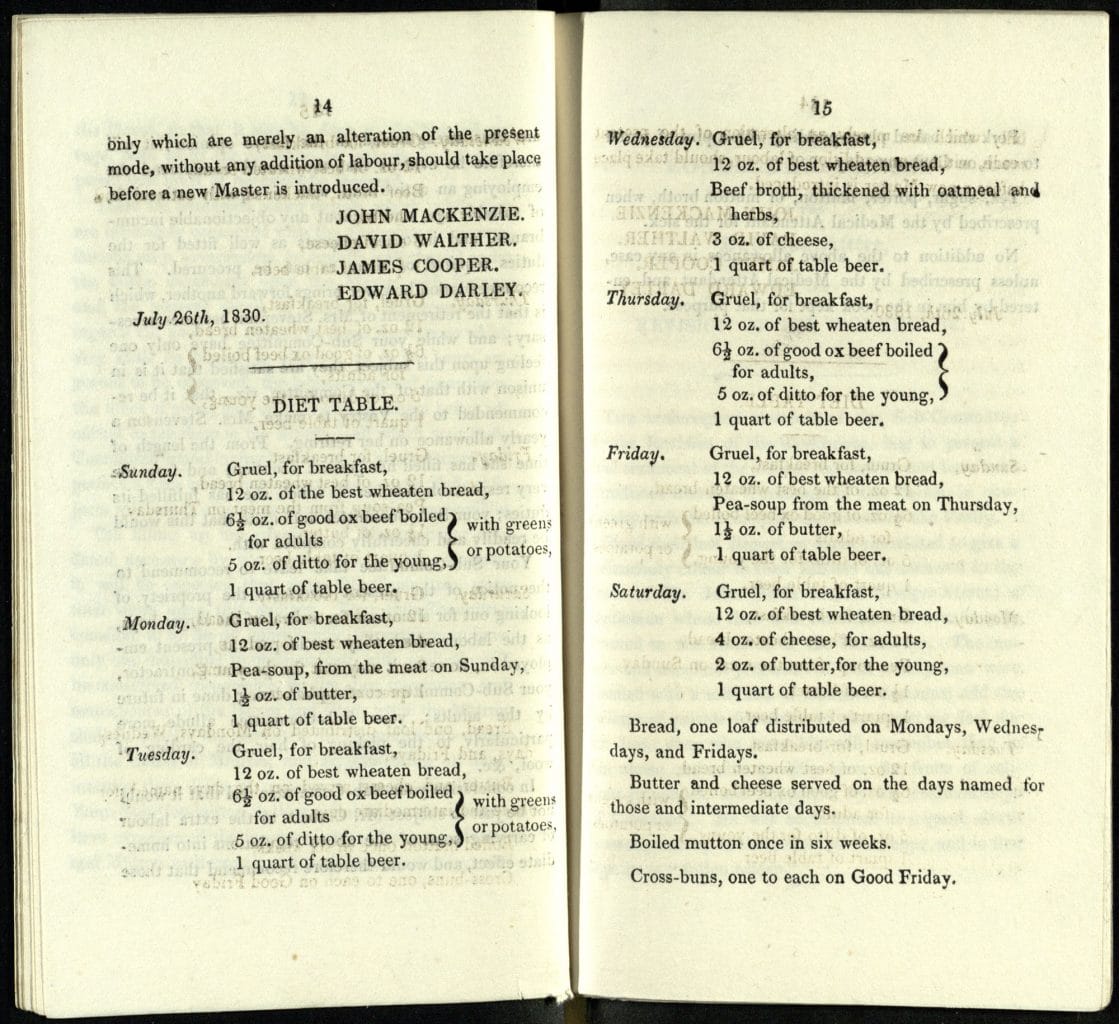

Recent historical research has shown that the picture of the Poor Law that Dickens created in Oliver Twist closely resembles the real thing as it operated inside the workhouse in Cleveland Street. The punishing regime used to discipline Oliver is very like that which prevailed at the time in Cleveland Street. The clearest instance of a parallel is perhaps that the official workhouse regulations published by Covent Garden Parish specifically forbade second helpings of food.

A ‘new-modelled diet table’ ordered gruel every day for breakfast, and an allowance of bread (no mention of butter) with ‘a portion’ of boiled meat on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. On each day following, the main meal was only soup, made from the broth in which the previous day’s meat had been boiled. On Saturday neither meat nor soup was given, but only a small portion of cheese. Tea, sugar, porter (ale), mutton or mutton broth, were permitted only on a doctors’ prescription. Fish was not mentioned, and pork made an appearance only once a year on Christmas Day, along with the only appearance of baked plum pudding. On Good Friday an Easter treat was allowed: ‘cross buns one to each’. Unless expressly prescribed by the Medical Attendant, and entered by him in the ledger devoted to that purpose, it was specifically emphasised twice that there was to be: ‘no addition to the above allowance in any case’, and ‘on no account any additional allowance to be given’.

Everyone knows what Dickens did with this: “Please Sir, I want some more”.

The sounds and smells surrounding the Cleveland Street Workhouse

The four-storey Workhouse in Cleveland Street and its burial ground were in active use throughout both periods that Dickens was living only a few doors away. The Workhouse inhabited an enclosed space, but it was not an entirely closed institution: what went on there influenced the locality in more ways than we can imagine. The many windows of the building’s frontage overlooked the street, so from across the road faces might be seen behind the glass, and perhaps human voices heard. The life of the entire institution was coordinated by the regular clang of the workhouse bell, which punctuated the working day within the institution at the hours of rising, working, dining and sleeping. A great workhouse bell intended to be heard in every ward and across the backyard and forecourt of this large institution can hardly have been inaudible in the surrounding streets. Other sounds might also have escaped beyond the walls of the institution: both the lying-in (maternity) ward and the ward for lunatics were at the front of the building, so on occasions moans and wails might have mingled and merged audibly outside. The overpowering smell of the place, which even Poor Law correspondents, who generally understated institutional shortcomings, referred to as ‘fetid exhalations’ was commented upon by Dr Rogers (the reforming doctor and Poor Law Medical Officer in the Workhouse), who also spoke with disgust of the choking clouds of dust from the paupers’ carpet-beating and stone-breaking, particles from which must surely have freighted the air in the streets nearby.The Workhouse gate was usually kept firmly shut. The gateman, whose double gatehouse stood on each side of the entrance, was expected to keep firm control over access. He required a written order from arrivals before opening the gate, searched visitors individually for ‘spiritous liquors’ as they entered, accepted and documented deliveries, checked all those who left the House, and noted everything in a great ledger. We do not know whether he was summoned by bell or knocker, but either would have been audible on the street as well as inside his gatehouse. Tradesmen, visitors, pauper funerals arriving for the graveyard, and pauper applicants for admission would all have had to wait outside until he verified their credentials. There would have been times, no doubt, when the queue was long.

Dickens’s inspiration

Further material has also come to light which suggests that Dickens used details from the locality of the Cleveland Street Workhouse in his writings, most especially in Oliver Twist. For example, Oliver’s cap is described as being of brown cloth – the same as the boys’ uniform in the Cleveland Street Workhouse, and the novel’s plot pivots on the possibility that the workhouse matron could be observed from the women’s wing of a workhouse, going to visit a pawnbroker’s. In Dickens’s day, a well-established pawnbroker’s shop stood at the top end of Norfolk Street, diagonally between the Workhouse and the corner house in which the Dickens family were lodgers. It was clearly visible from the windows of both places. If you stand on the same corner today, where the pawnbroker’s shop used to be, you can still see both Dickens’s old home (which now has a blue plaque) and the upstairs windows of the Workhouse’s women’s wards, from where the elderly female inmates could have secretly scrutinised the matron’s errand.But perhaps the most convincing evidence that Dickens used Cleveland Street in Oliver Twist is that right opposite the Workhouse, was a tallow-chandler’s shop selling candles and cheap rushlights made of animal fat (tallow). The signboard outside is likely to have been painted with the proprietor’s business and his name. Who was he? A man named Bill Sykes, just the same as the murderer in Oliver Twist.

The text in the article is © Dr Ruth Richardson. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Ruth Richardson

Ruth Richardson is an independent scholar, a Visiting Fellow at King’s College London and Visiting Professor at Hong Kong University. A devoted reader in the British Library’s Rare Books Room, she is the author/editor of several books including Death, Dissection and the Destitute, Vintage Papers from the Lancet, Medical Humanities, The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy and most recently, Dickens and the Workhouse. She has published many papers in learned journals, created online exhibitions for King’s College Special Collections and for the Bishopsgate Institute, and is a frequent contributor to The Lancet. She is currently working on a study of marginalia and topography in Dickens and Tennyson, and working to preserve the Cleveland Street Workhouse.