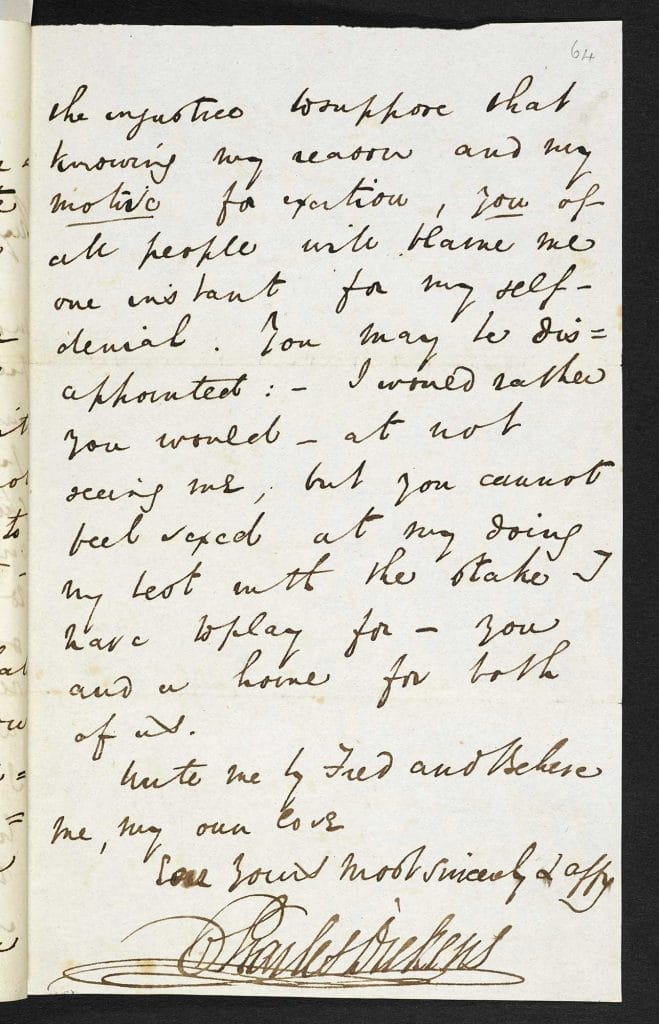

Crime in Oliver Twist

Dickens‘s Oliver Twist depicts the excitement as well as the danger surrounding the criminal underworld. Here Professor Philip Horne examines how Dickens’s portrayal of crime was influenced by public executions, contemporary criminal slang and other sensational literary works.

From childhood, Charles Dickens had an intense, even nightmarish sense of the looming threat of crime – the possibility of being its victim, but even worse that of becoming one of its perpetrators, its addicts, its devotees. Oliver Twist (1837–39) has been adapted many times for various forms, and famously turned into a musical (Lionel Bart’s Oliver! (1960)). Indeed, some of its criminal characters – Fagin, Bill Sikes, the Artful Dodger – have become legends. But for Dickens it wasn’t so jolly: even if dark humour and an acute sense of the grotesque never left him, the lure of crime was a matter of life and death, the saved and the damned. Dickens saw the pull of crime as a literary genre – his novels benefited from the topic’s wide appeal. And yet he insisted on crime’s seriousness, and saw that thrilling, enticing literature was part of the same world as the misery of real, blighting wrongdoing. In an era of public executions, which he more than once attended, Dickens saw the shadow of the gallows fall over a whole society.

Dickens’s childhood

As we know from his fragment of a memoir, printed in John Forster’s Life of Dickens (1872–4), after his father was imprisoned for debt, the 12-year-old Charles was sent to work in Warren’s blacking factory pasting labels on blacking bottles. Dickens remembered the experience both as a humiliation, and as a descent into the amoral world of London lowlife. ‘But for the mercy of God, I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a little vagabond’. Like the ‘young vagabond’ Oliver, that is, only narrowly avoiding adoption by a sinister Fagin (ch. 11). Dickens sees the possible other path his life might have taken: when he declares in his 1841 Preface that ‘I wished to show, in little Oliver, the principle of Good surviving through every adverse circumstance, and triumphing at last’, he needn’t be taken as suggesting Oliver could resist any temptation, but rather that he was also lucky, maybe protected by Providence.

The romance of crime

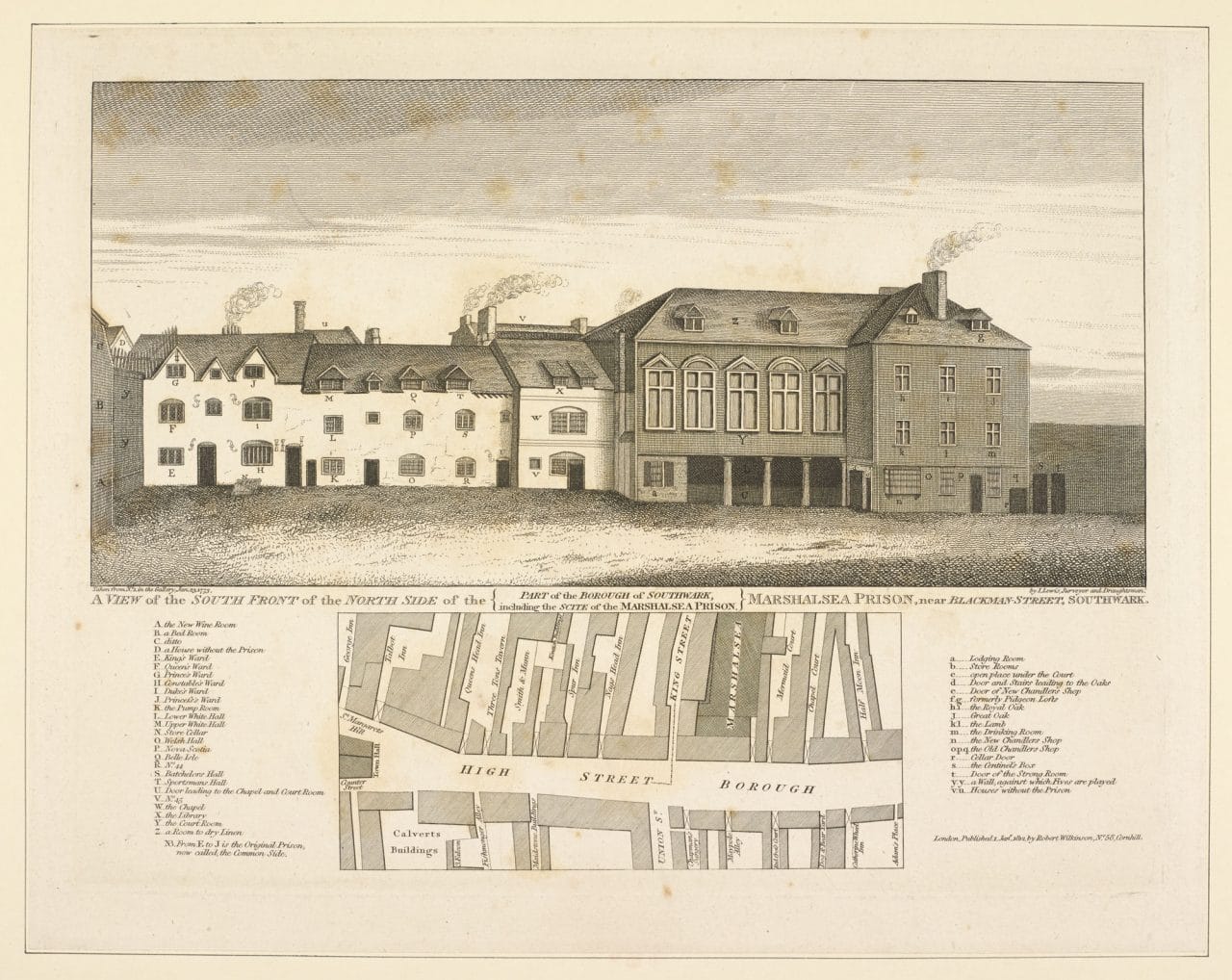

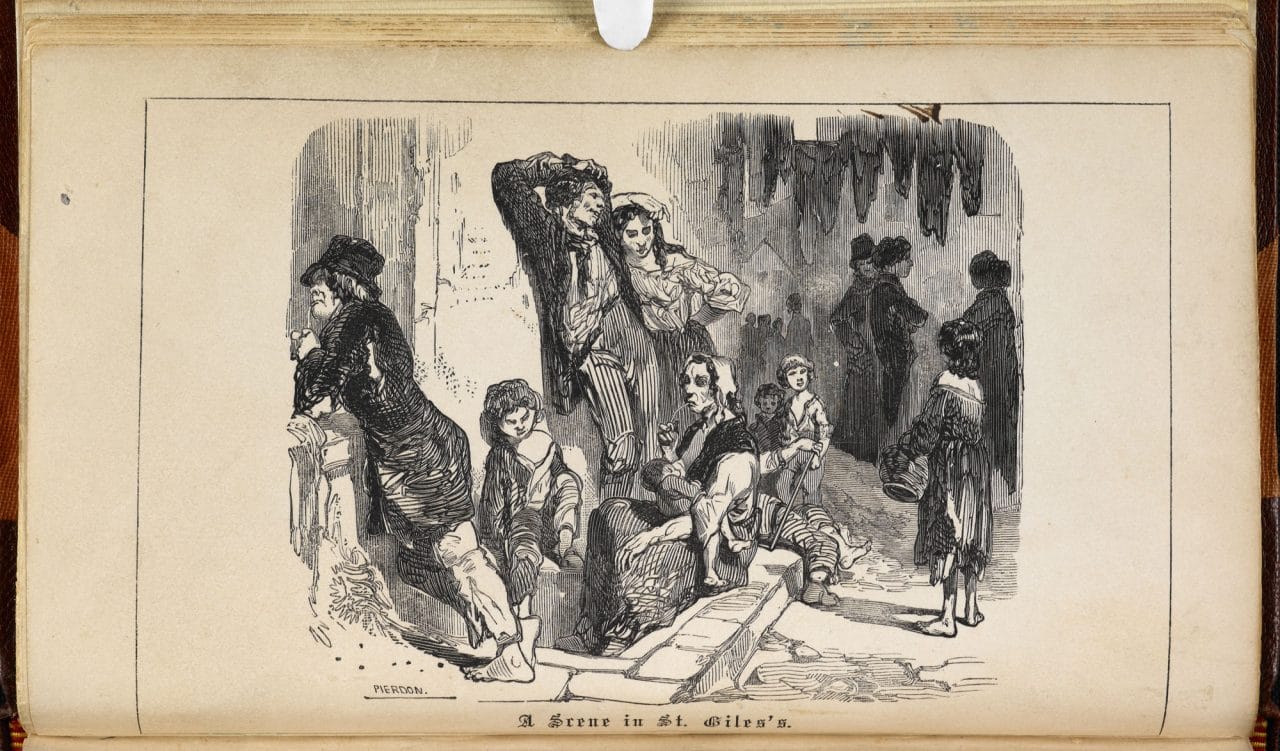

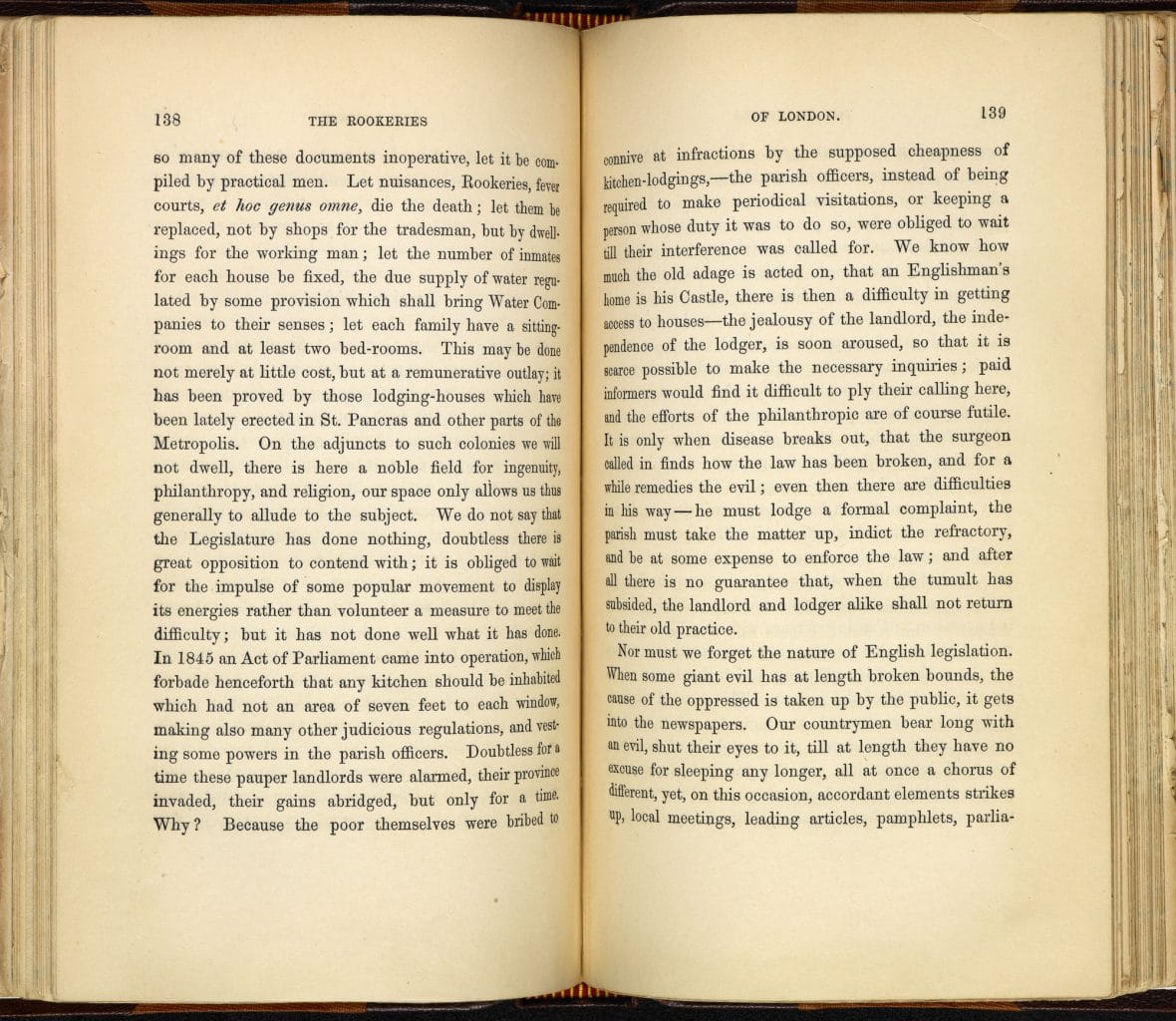

Dickens felt too, of course, the romantic attraction of crime. John Forster famously wrote of the glamour and excitement that drew Dickens even as a 10-year-old boy to the criminal parts of London know as ‘rookeries’, recording that he was both fascinated and repulsed by the worlds he found there.

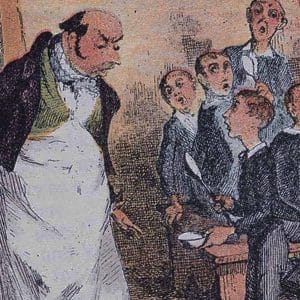

For Oliver Twist, Dickens chose as his subject matter London’s criminal underbelly, filling the novel with pick-pockets, prostitutes, murderers and house-breakers – thus horrifying many of his readers. The rawness of the novel didn’t appeal to the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, for instance – as recorded in the young Queen Victoria’s diary: ‘It’s all among Workhouses, and Coffin Makers, and Pickpockets’, he grumbled. ‘I don’t like those things; I wish to avoid them; I don’t like them in reality, and therefore I don’t wish them represented.’ (Victoria herself felt it was ‘excessively interesting’.) In the preface to the 1841 edition Dickens wrote: ‘It is, it seems, a very coarse and shocking circumstance, that some of the characters in these pages are chosen from the most criminal and degraded of London’s population; that Sikes is a thief, and Fagin a receiver of stolen goods; that the boys are pickpockets, and the girl is a prostitute … It appeared to me … to paint them in all their deformity, in all their wretchedness, in all the squalid poverty of their lives; to show them as they really are, for ever skulking uneasily through the dirtiest paths of life, with the great, black, ghastly gallows closing up their prospect, turn them where they may; it appeared to me that to do this, would be to attempt a something which was greatly needed, and which would be a service to society. And therefore I did it as I best could.’

Criminal slang and hanging metaphors

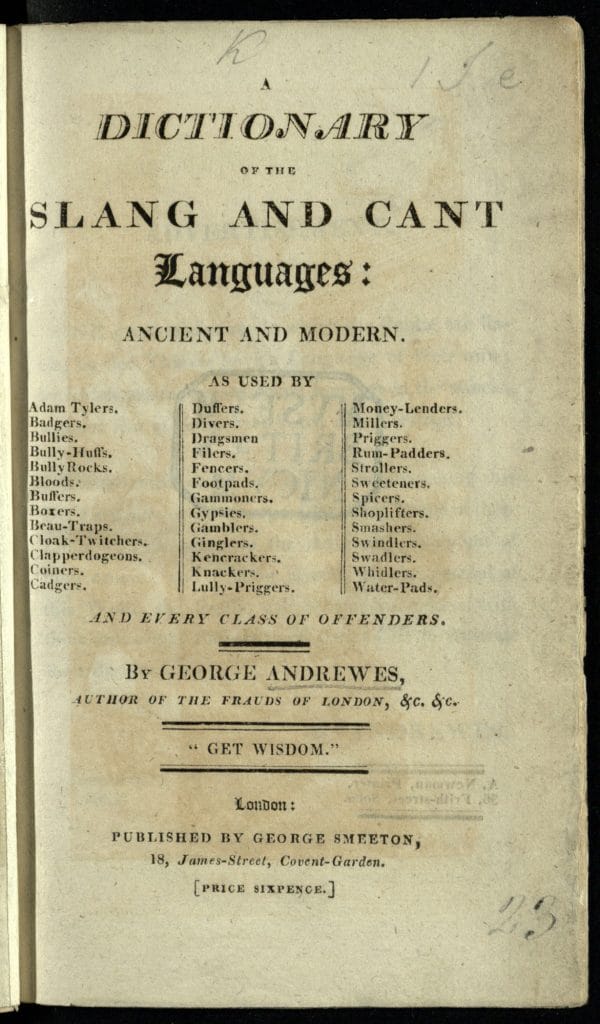

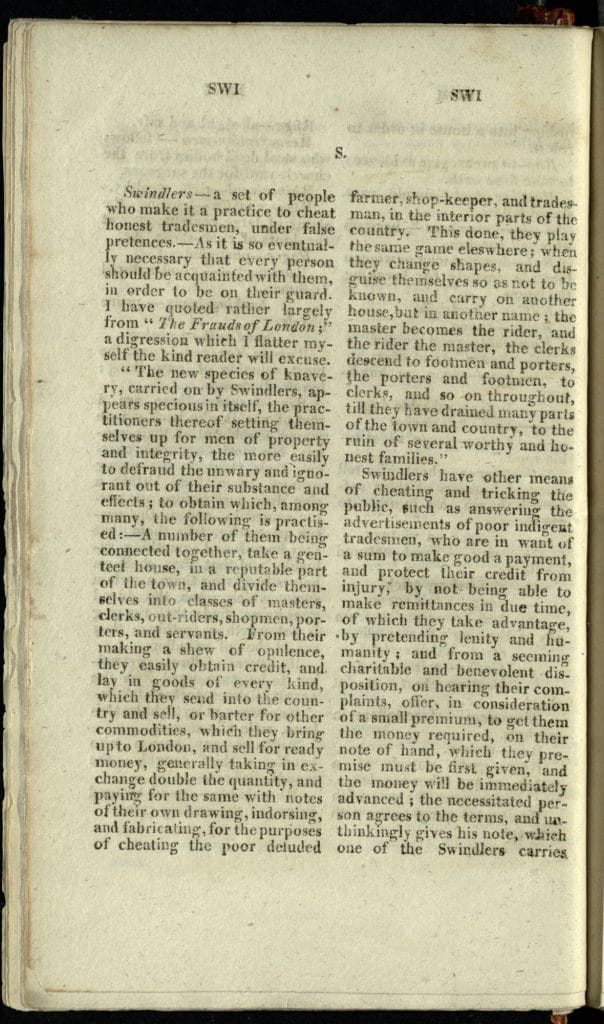

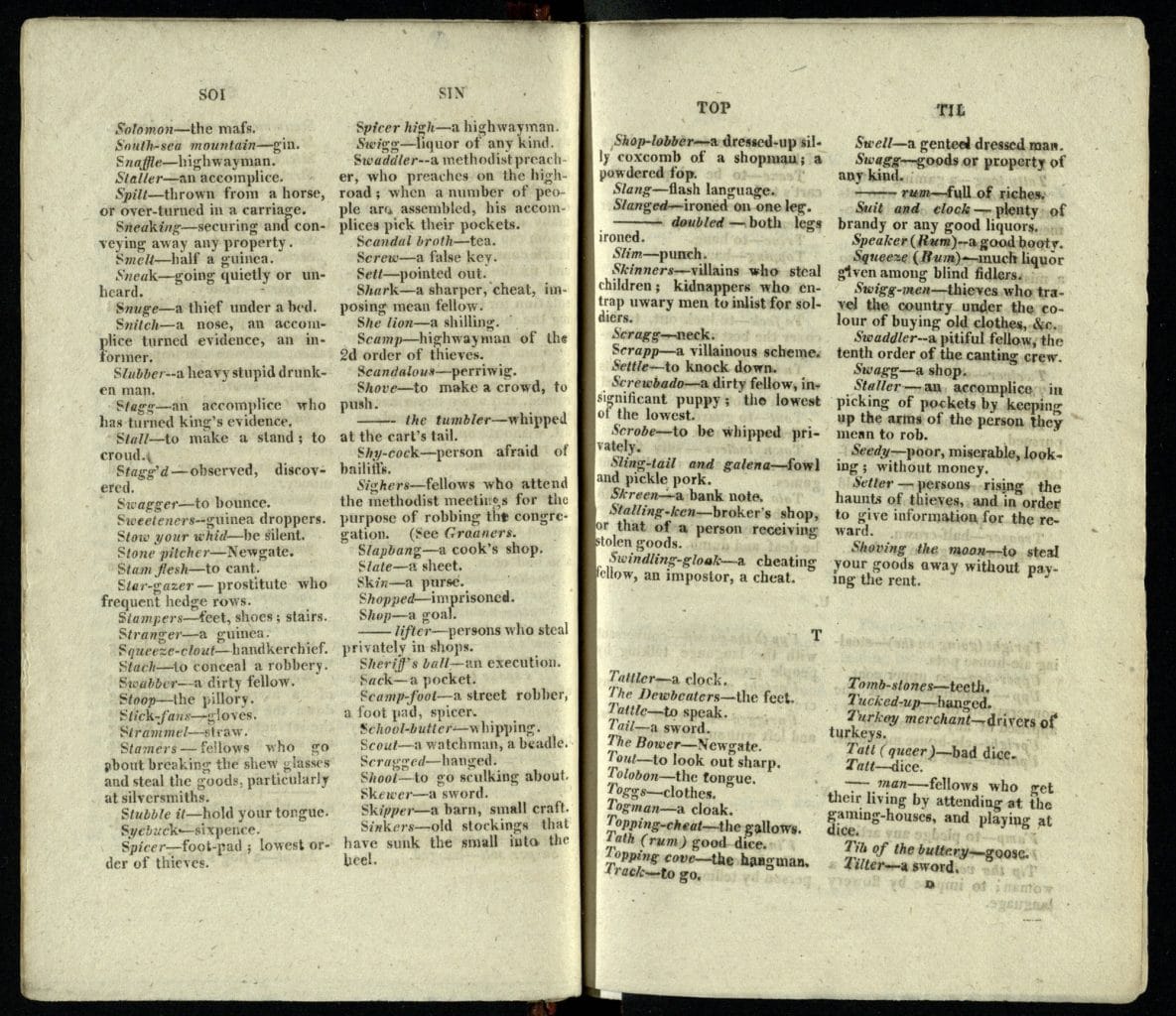

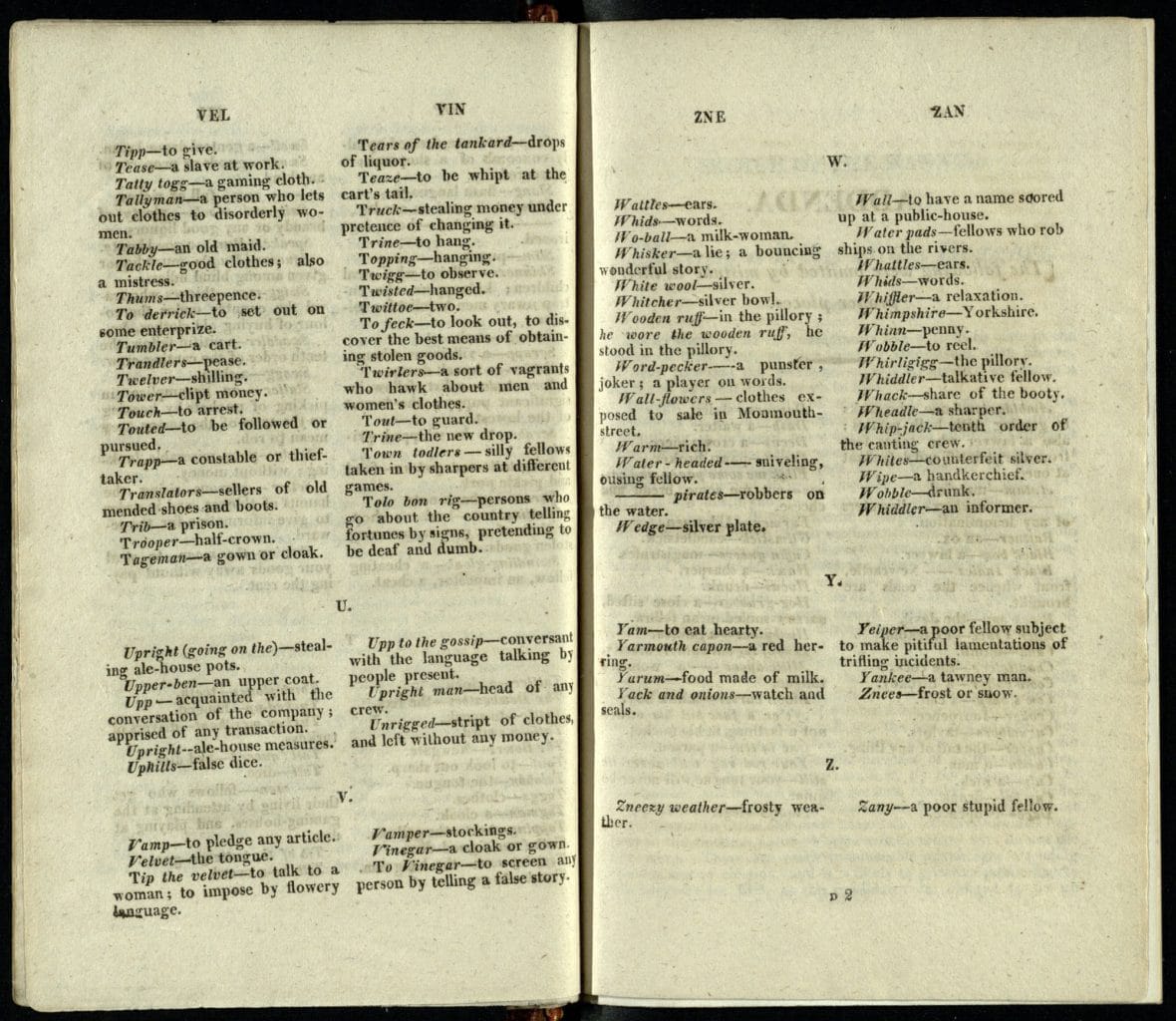

Dickens, who as a former reporter believed in active research and direct experience as well as exercising his astonishing imagination, consciously fills his novel with what is known as ‘Thieves’ Cant and Slang’ – of which there were many popular dictionaries and lexicons in print (e.g. ‘A new and comprehensive vocabulary of the flash language’[1] ((1812) by James Hardy Vaux, himself an ex-convict). For example, Toby Crackit says encouragingly to the Dodger: ‘You’ll be a fine young cracksman afore the old file now’ (cracksman = house-breaker; old file = old fraud) (ch. 25). The small Oliver himself is taken on the Chertsey burglary to carry out an authentic ‘rig’ or trick, his role being exactly as defined in Francis Grose’s 1796 Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue[2] : ‘LITTLE SNAKESMAN. A little boy who gets into a house through the sink-hole, and then opens the door for his accomplices; he is so called, from writhing and twisting like a snake, in order to work himself through the narrow passage.’ But before that he finds himself being initiated to the traditional first step in a criminal career – pickpocketing, which can lead all to insidiously to the gallows.

Dodger and the other pickpockets, go off to witness (and ‘make pocket-handkerchiefs’ – pick pockets) at the execution of boys like them – boys Fagin has informed on for the reward. When they get back, Fagin asks them ‘whether there had been much of a crowd at the execution that morning’ (ch. 9) – suggesting what may lie in store for Oliver.

Under the so-called ‘Bloody Code’ of capital punishment for a wide variety of property-related crime, small beginnings – in pickpocketing and burglary – could all too easily lead to conviction and death – though criminals used ‘gallows humour’ to put up a psychological barrier of bravado. Thus thieves’ cant is rich in terms for hanging, e.g. to be crapped, frummagemmed, jammed, nubbed, topped, tucked up; to dangle, dance upon nothing, die of hempen fever. Hanging is in fact the fate most often predicted for Oliver in the novel. His very name predicts it: one slang sense of ‘twisted’ was ‘hanged’ – the usage comes from ‘twisting as one swings on the rope’. In the workhouse, the gentleman in the white waistcoat repeatedly announces that ‘That boy will be hung’ (ch. 2). He’s not the only one: Noah Claypole, Fagin, a travelling tinker who helps capture Oliver after the Chertsey burglary, Monks – they all predict it, and seem eager to help it come about.Fagin, who harrowingly faces the gallows at the end, is early on overheard by Oliver muttering to himself, ‘What a fine thing capital punishment is!’ (ch. 9). He likes it because it’s useful to him – as a threat he holds over his gang, and even a means of profit (he informs on his colleagues for money). He spells it out to Noah Claypole that if he breathes a word against the gang, then Fagin will have to blow upon him, (the thieves’ cant phrase for informing on him), for his crime is a capital one. Stealing from Sowerberry ‘would put the cravat round your throat that’s so very easily tied, and so very difficult to unloosen, – in plain English, the halter!’ (ch. 43). In fact, the novel ties together symbolically handkerchiefs criminally picked from pockets, those sported as neckwear, the hempen ‘cravat’ of the hangman and all the various associations with throats or ‘windpipes’ – choking, strangling, clasping, tearing and cutting.

The attraction of repulsion

As this profusion of metaphors shows, Dickens was preoccupied with capital punishment (and changed his mind about it over time): the gallows – which was a punishment not only for murder but for all sorts of smaller felonies – looms large in many of his works (e.g. Barnaby Rudge, Great Expectations). This wasn’t just a personal quirk. The thirty-five years up to Oliver Twist saw 103 death-sentences passed on children under 14 for theft (this was controversial, and happily none were carried out). In 1830 18,017 felony prosecutions were brought under the capital (‘bloody’) code. It was a time of reaction and repression, social unrest and anxiety among the propertied class, in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Thus twice as many people were hanged in the first 30 years of the 19th century as in the last half of the 18th century. Two-thirds of the 671 hangings in the 1820s were for property crime, only one fifth for murder.[3]

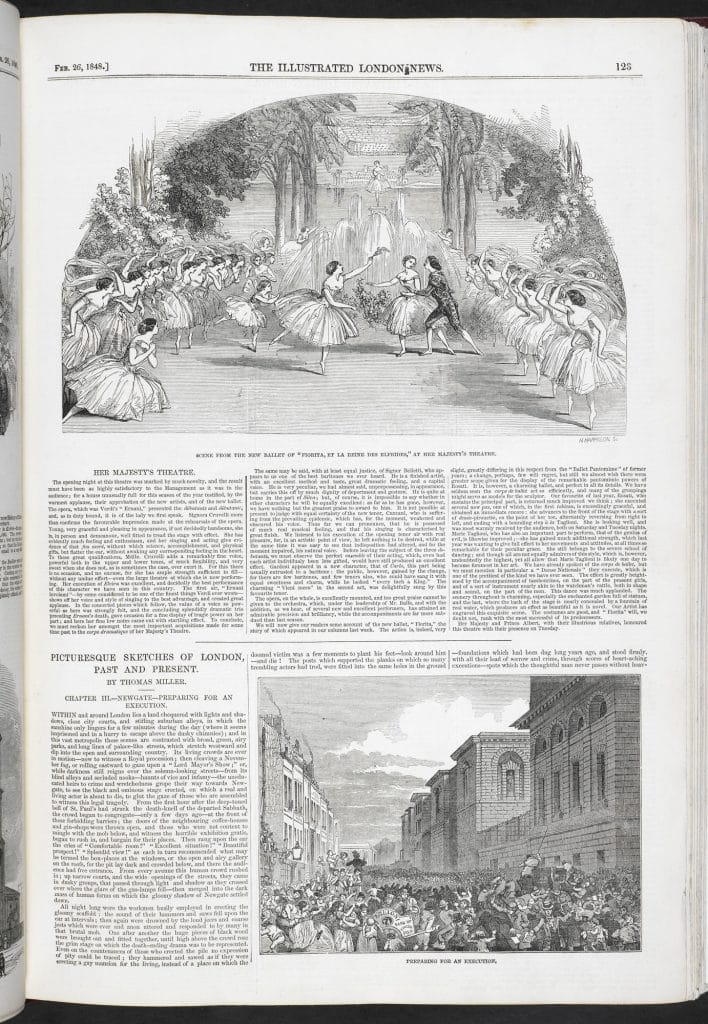

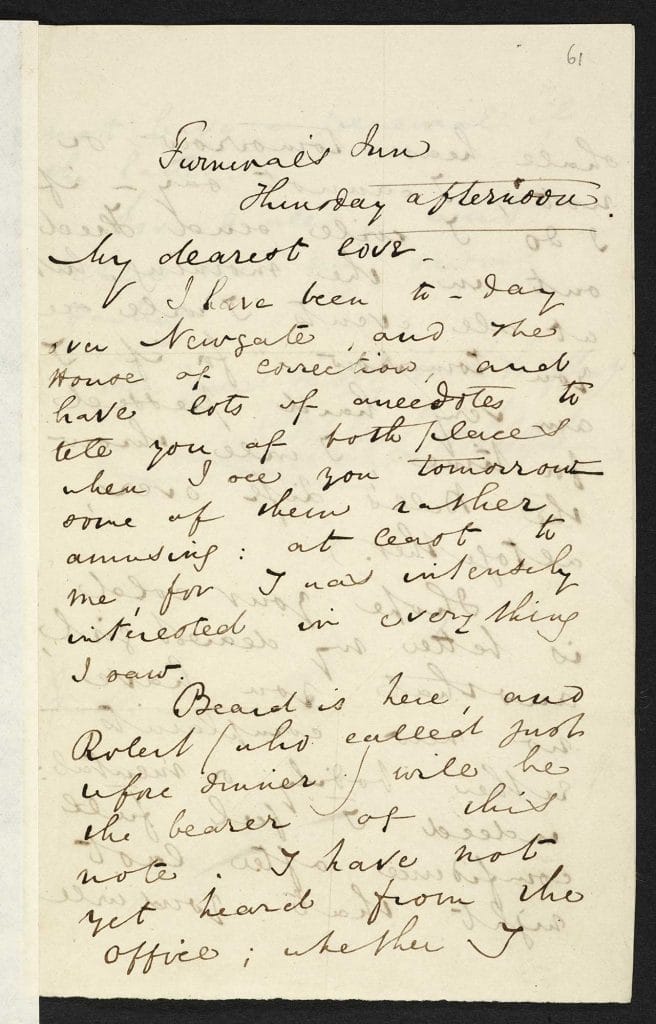

Hangings were public, and their audiences frequently vast (crowds of up to 100,000 were claimed). Even before writing Oliver Twist, Dickens already felt their gruesome fascination – as he wrote in an 1835 letter: ‘You cannot throw the interest over a year’s imprisonment, however severe, that you can cast around the punishment of death. The Tread-Mill will not take the hold on men’s feelings that the Gallows does’.

We see such a ‘hold on men’s feelings’ in Oliver Twist – it permeates the novel: Fagin’s conviction at the Old Bailey is met with ‘a peal of joy from the populace outside, greeting the news that he would die on Monday’ – the usual day for executions. When Oliver leaves the maddened Fagin in the death-cell, he sees no ‘suitable emotion’ outside: ‘the crowd were pushing, quarrelling and joking’ (ch. 52).

Images of the Gallows

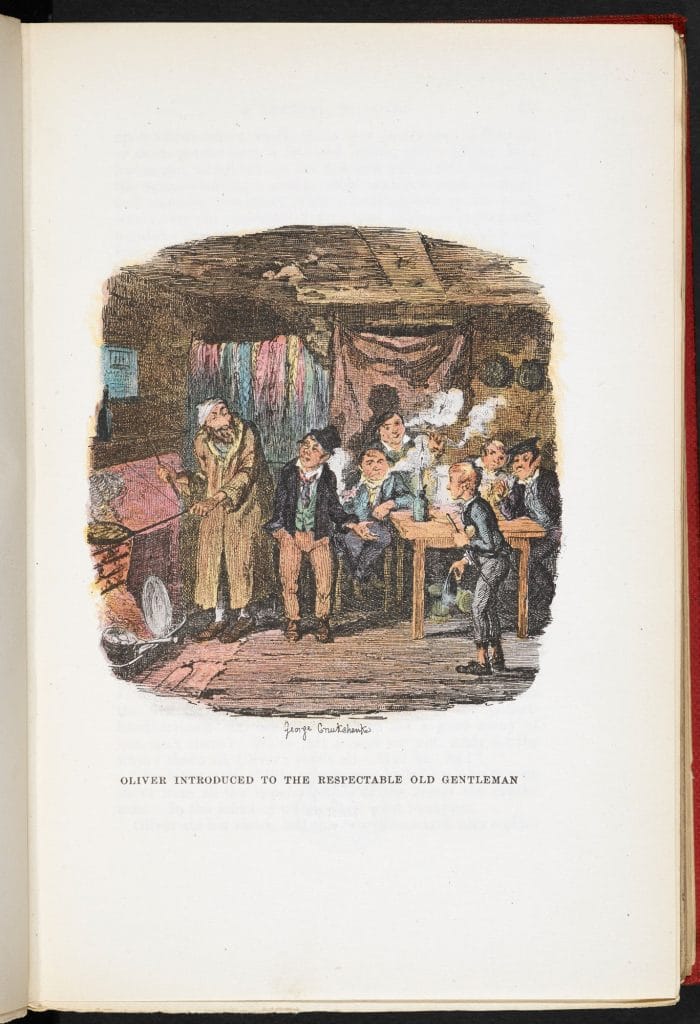

Dickens simply says the walls at Fagin’s ‘were perfectly black with age and dirt’ (ch. 8), but in the illustration to this passage by the great George Cruikshank there is a broadsheet above the fire – the tabloid-style single-sheet poster popular at the time, purveying prurient, moralistic ballads with brutal woodcuts and lurid details thrown in. It depicts three hanged criminals on the gallows. In the illustration, a potent diagonal leads from the handkerchief filled with belongings in Oliver’s hand to the kerchief round the Dodger’s neck, then to the one knotted on Fagin’s head, and finally to the triple noose on the wall. This composition displays the path to the gallows Oliver is in danger of treading. Cruikshank sometimes worked from a verbal summary without actually seeing the text; so Dickens could be inspired by his collaborator’s images. When Dickens has Fagin soliloquize approvingly about capital punishment in Chapter 9, he has him mention that there were ‘Five of them strung up in a row’ – picking up Cruikshank’s broadsheet (and adding two more for luck).

Depictions of the urban underworld

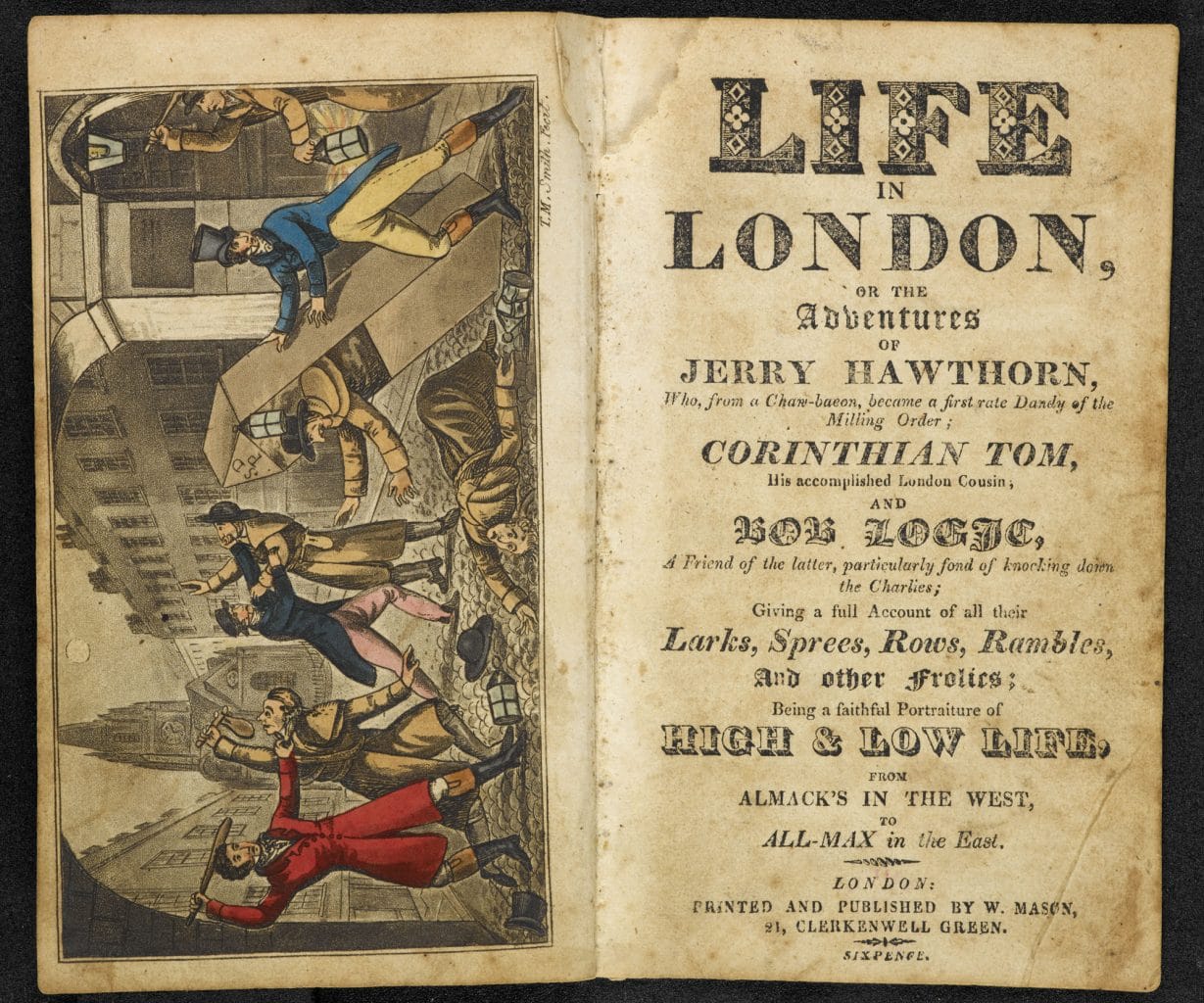

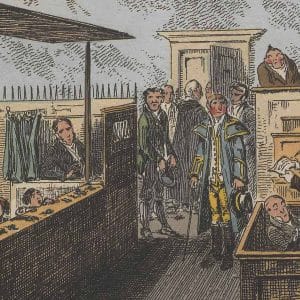

The glamorous mythography of London crime had already a rich literature. For instance, Pierce Egan’s bestselling Life in London of 1821, illustrated like Oliver Twist by the great George Cruikshank, had made the underworld a site for urban tourism – a fashionable, thrilling but cosy image of the unrespectable. Egan’s heroes Tom and Jerry go slumming in the ‘flash’ world of the criminal and sporting fraternities on comic ‘Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis’, but in a comic spirit and always with a safe escape route back to the comforts of the rich West End.

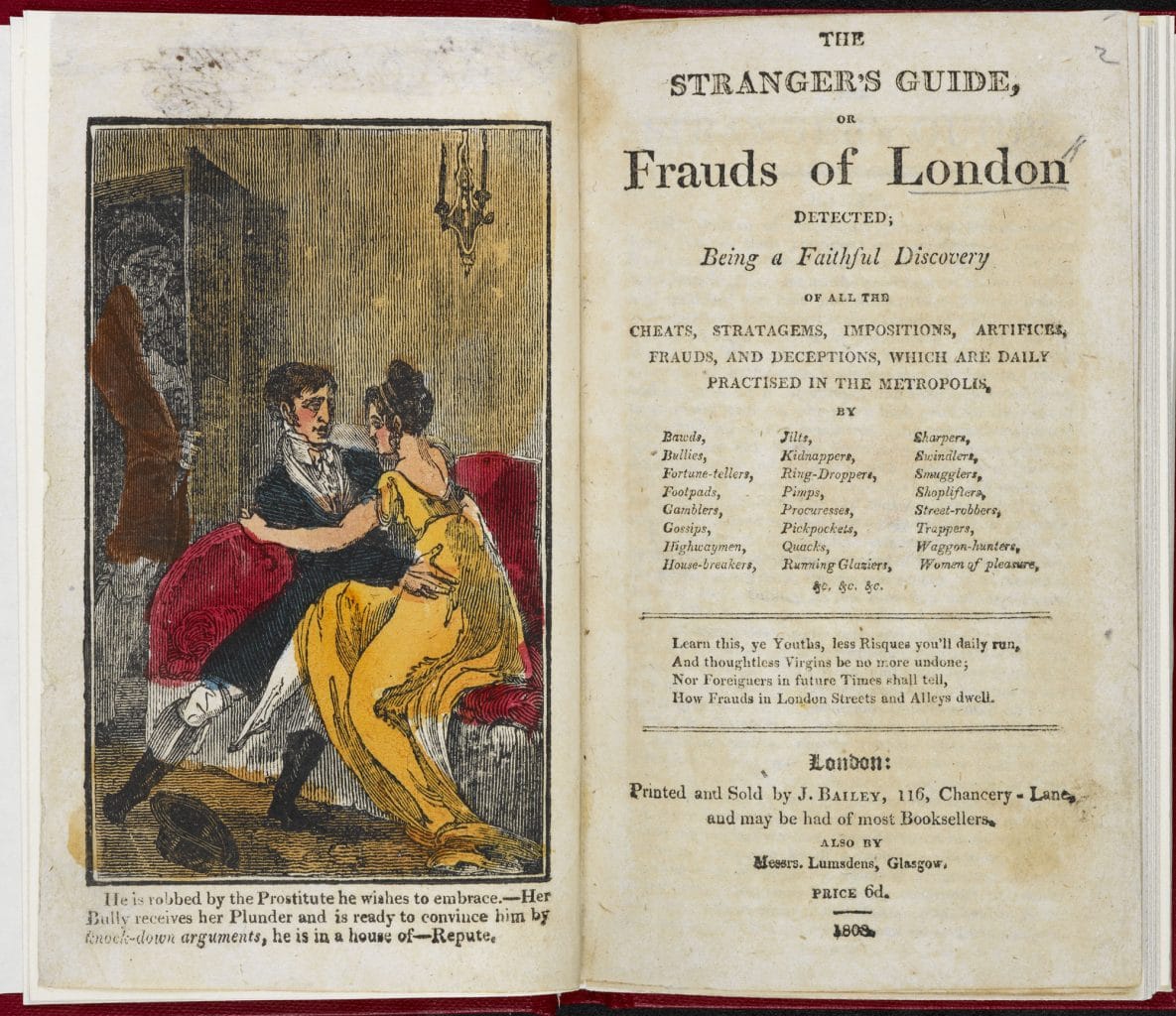

There were also numerous guidebooks to urban lowlife, aimed at potential victims, like The Stranger’s Guide, or Frauds of London Detected, Being a faithful Discovery of all the Cheats, Stratagems, Impositions, Artifices, Frauds, and Deceptions, which are daily practised in the Metropolis (1808). The title page of this alluring work offers a long list of London’s lowlife predators, including swindlers, shoplifters, pickpockets, kidnappers, house-breakers and women of pleasure. Its frontispiece shows the image of a metropolitan den of vice – a prostitute embracing her unsuspecting client, behind whom her ‘Bully’ lurks, ready to extort money by blackmail and if necessary violence. The appetite for images and narratives of crime, corruption and violence has deep roots – which Dickens explores in Oliver Twist – but Egan and The Stranger’s Guide offer sanitized, wishful versions of something Dickens recognised was dark and ugly.

Oliver Twist and the ‘Newgate Novel’

The particular tradition Dickens was confronting was at least a century old. When he is first locked up by Fagin, Oliver is left with a book – ‘a history of the lives and trials of great criminals’. The ‘terrible descriptions were so vivid and real, that the sallow pages seemed to turn red with gore’. This is the Newgate Calendar, dating from 1728 but much reprinted, the great book of English crime, and it sends Oliver into ‘a paroxysm of fear’ (ch. 20). With the vogue for criminal subjects that Oliver Twist was an attempt to deglamorise (but which its success mostly boosted), there was in the late 1830s a controversy over the sensationalisation of crime in the literary genre known as the ‘Newgate Novel’.

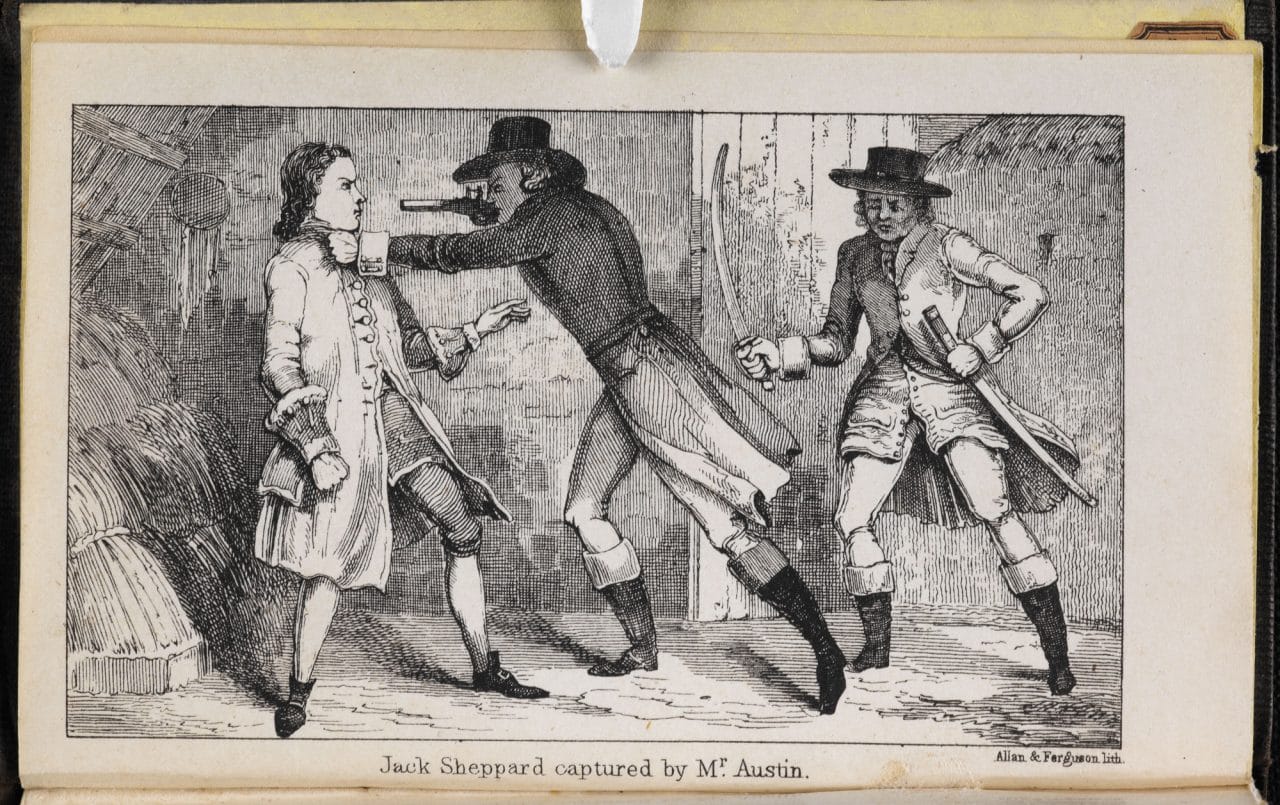

Dickens was disgusted that Oliver Twist became caught up in the controversy. His friend the novelist Harrison Ainsworth wrote a new Preface to his novel Rookwood (a frenzied, sexy and violent melodrama of illegitimacy, tombs, oaths, curses, poison, disputed inheritances and concealed identities) in October 1837, praising the account of criminal lives in London in Oliver Twist; and things got worse when Ainsworth’s next big hit, Jack Sheppard, based on the exploits of a notorious 18th-century thief (immortalised in the Newgate Calendar), overlapped with the last four instalments of Oliver Twist.

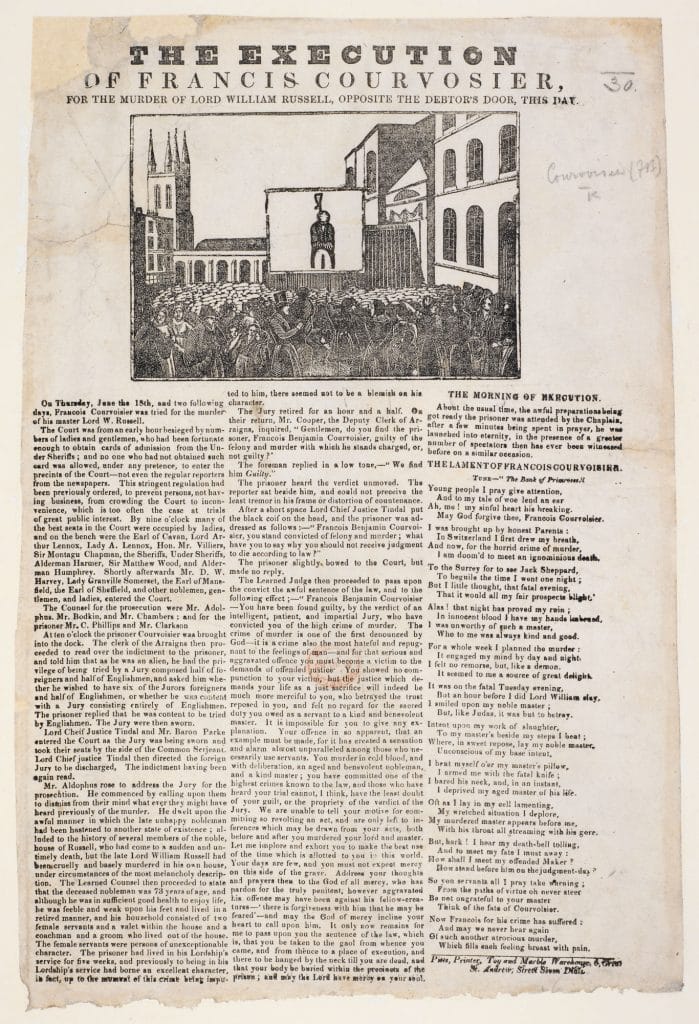

The controversy intensified when on 5 May 1840, a valet named François Courvoisier murdered his 72-year-old master, Lord William Russell; because Courvoisier subsequently proclaimed, allegedly at least, that he had been corrupted by reading or seeing the dramatisation of Jack Sheppard. The case was a sensation. On the morning of Monday 6 July 1840, Courvoisier was hanged before a crowd of about 30,000, including Dickens – who responded intensely.

In February 1846 (while revising Oliver Twist), Dickens wrote a long and powerful letter to the Daily News showing his deep concern with the subject. The letter harks back to Dickens’s experiences at Courvoisier’s hanging in 1840: he judges that ‘It was so loathsome, pitiful, and vile a sight, that the law appeared to be as bad as [Courvoisier], or worse; being very much the stronger, and shedding around it a far more dismal contagion.’ He also notes that

From the moment of my arrival, when there were but a few score boys in the street, and those all young thieves … – down to the time when I saw the body with its dangling head, being carried on a wooden bier into the gaol – I did not see one token in all the immense crowd; at the windows, in the streets, on the house-tops, anywhere; of any one emotion suitable to the occasion. No sorrow, no salutary terror, no abhorrence, no seriousness; nothing but ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness, and flaunting vice in fifty other shapes. I should have deemed it impossible that I could have ever felt any large assemblage of my fellow-creatures to be so odious.

His conclusion is profound:

The attraction of repulsion being as much a law of our moral nature, as gravitation is in the structure of the visible world, operates in no case (I believe) so powerfully, as in this case of the punishment of death.

It does not seem a coincidence that when he wrote this Dickens was revising Oliver Twist, perhaps his greatest evocation of ‘the attraction of repulsion’.

脚注

- James Hardy Vaux, A New and comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash language (1819)

- Francis Grose, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (London, S.Hooper, 1788)

- These figures come from V A C Gatrell’s superb study,, The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People, 1770-1868 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 4, 19, 7.

Some rights reserved: ‘Crime in Oliver Twist’ by Professor Philip Horne © Philip Horne. This item can be used for your own private study and research. You may not use this work for commercial purposes.

撰稿人: Philip Horne

Professor Philip Horne teaches in the department of English at University College London. His current research interests—apart from Henry James—include literary allusion, literature and politics, and the relations between the living and the dead in film.