Orphans in fiction

Why do orphans appear so frequently in 19th-century fiction? Professor John Mullan reflects on the opportunities they provide for authors, considering some of the most famous examples of the period.

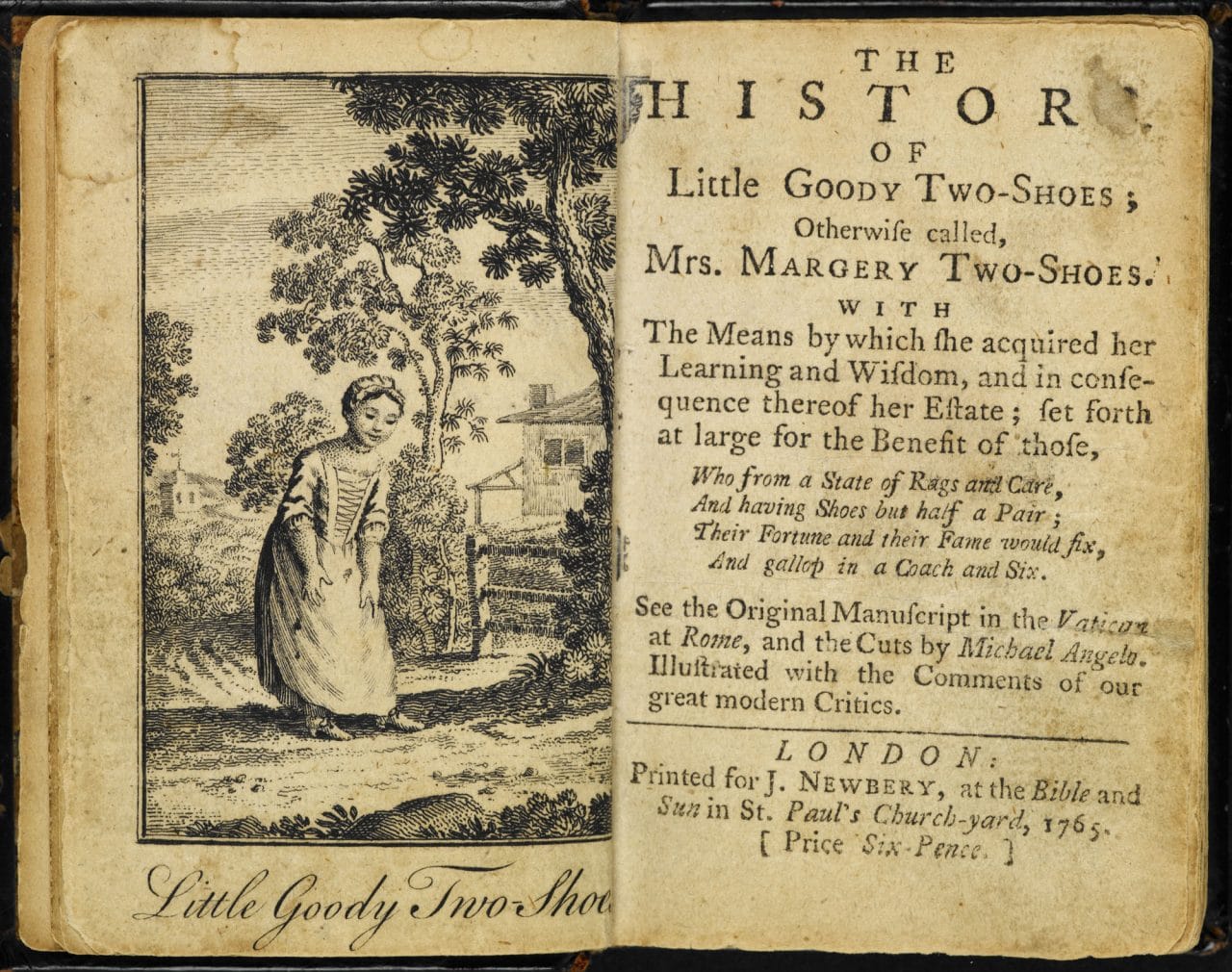

It is no accident that the most famous character in recent fiction – Harry Potter – is an orphan. The child wizard’s adventures are premised on the death of his parents and the responsibilities that he must therefore assume. If we look to classic children’s fiction we find a host of orphans. The child heroine of one of the earliest popular children’s stories, Little Goody Two-Shoes, (published by John Newbery in 1765) was an orphan. Protagonists of The Secret Garden, Anne of Green Gables, Tom Sawyer, and Ballet Shoes, to name a few, are also orphans. Their stories can begin because they find themselves without parents, unleashed to discover the world. Thus Orphan Annie (the good-hearted and resilient child heroine first of a hugely popular comic strip in the USA, then of a radio show, film and musical) wanders through a sometimes wicked world, revealing the qualities of others, herself untainted by folly or corruption.

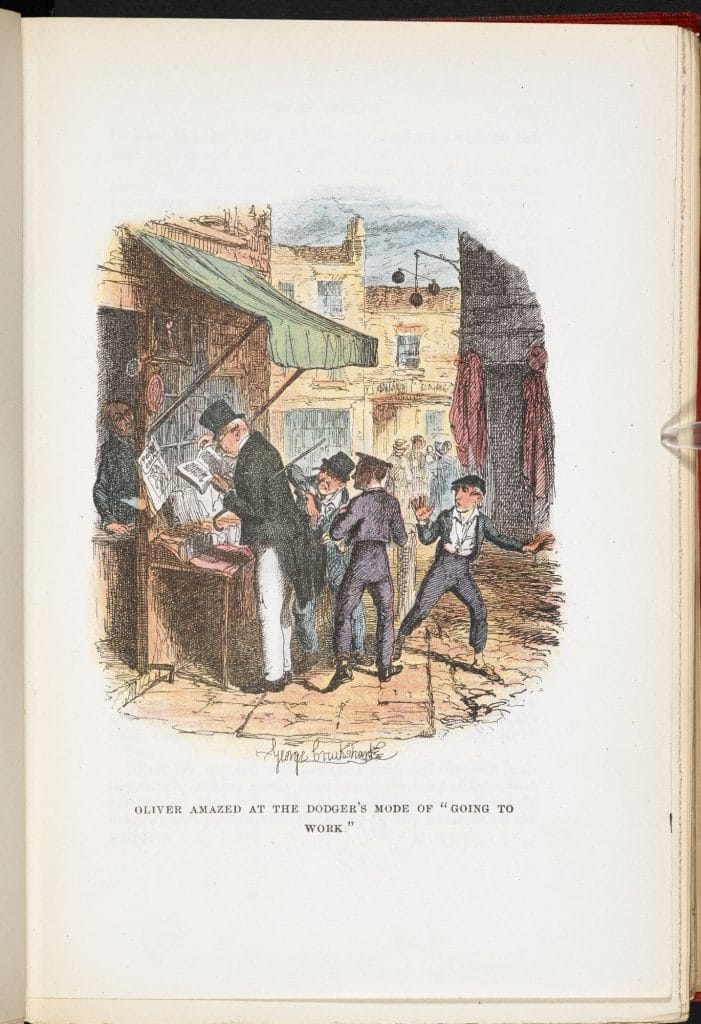

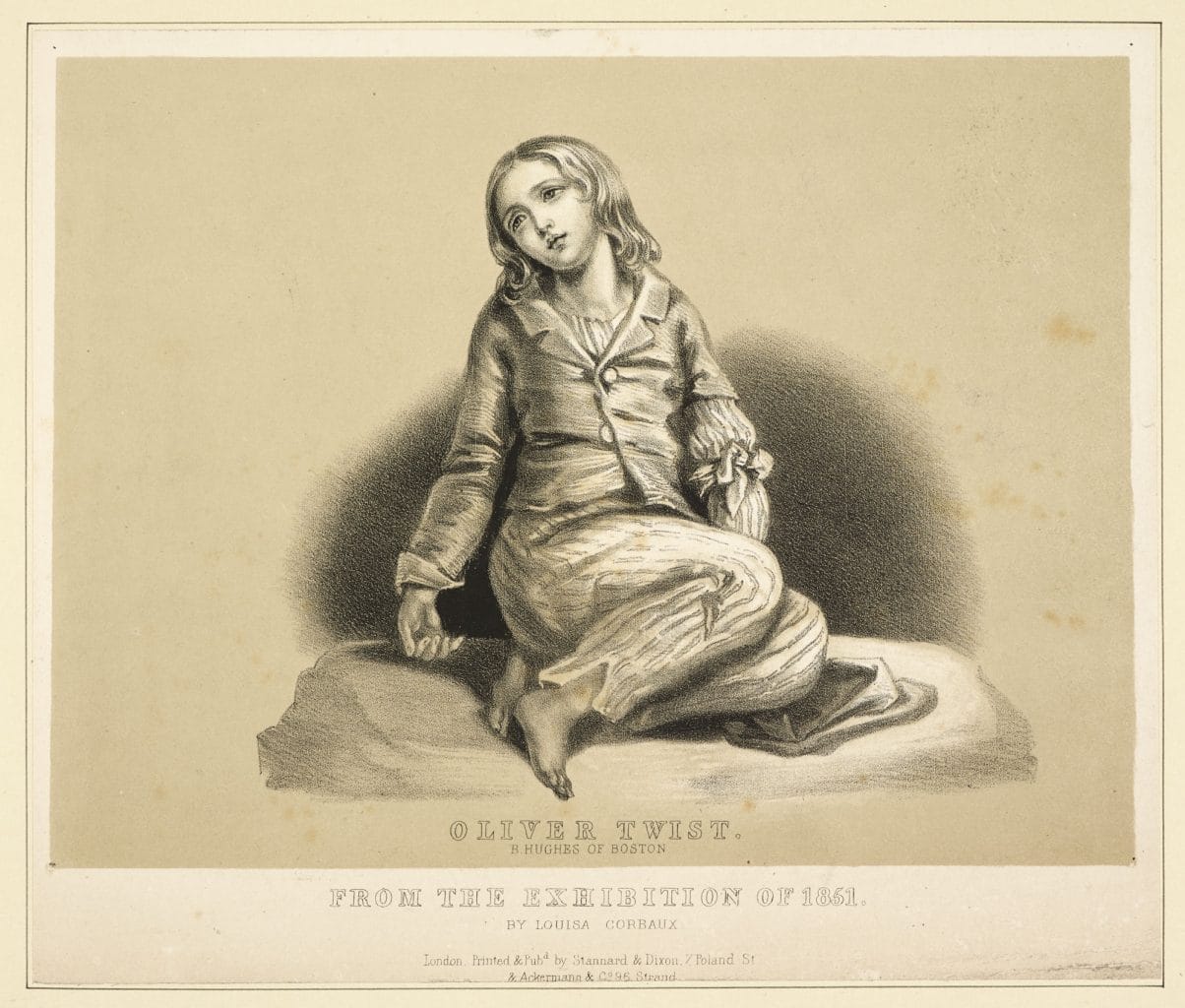

The orphan is above all a character out of place, forced to make his or her own home in the world. The novel itself grew up as a genre representing the efforts of an ordinary individual to navigate his or her way through the trials of life. The orphan is therefore an essentially novelistic character, set loose from established conventions to face a world of endless possibilities (and dangers). The orphan leads the reader through a maze of experiences, encountering life’s threats and grasping its opportunities. Being the focus of the story’s interest, he or she is a naïve mirror to the qualities of others. In children’s fiction, of course, the orphan will eventually find the happiness to compensate for being deprived of parents. Dickens’s Oliver Twist, who remains virtuous and innocent despite the criminal company he keeps, is comparable with these characters from children’s fiction. Like many of them, he discovers inherited affluence, but along the way reveals to the reader the secrets of London’s criminal underbelly.

Vulnerability and the governess

Any author interested in the vulnerability of children is likely to think of orphans. Miles and Flora in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw are the prey of malign spirits because they have no parents, only a permanently absent guardian. Their governess, the novella’s main narrator, knows she is their only saviour. Ironically, being a governess is commonly the occupation of orphans in 19th-century novels. An early example is Jane Fairfax in Jane Austen’s Emma, who, as an orphan, is entirely dependent on the kindness of others. She survives as the live-in companion to a close (and affluent) friend, but when that friend marries she must look for another way of sustaining herself. When her secret engagement to Frank Churchill collapses, it appears that she will have to become a governess. She calls this occupation a kind of slavery.The governess is another recurring literary motif. Like the orphan, she is betwixt and between, superior to any servant, yet not a member of the family. In novels, the job naturally belongs to an orphan, who has no certain class identity. The most notorious anti-heroine of Victorian fiction, Becky Sharp in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, is an orphan who becomes a governess – though in her case the job is the first rung on her climb up through society. Like other literary orphans who become governesses, she is more educated and accomplished than those who employ her. The alluring governess Lucy Graham in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Victorian bestseller Lady Audley’s Secret is inevitably an orphan, as was Miss Wade, the sinister governess in Dickens’s Little Dorrit.

Adoption

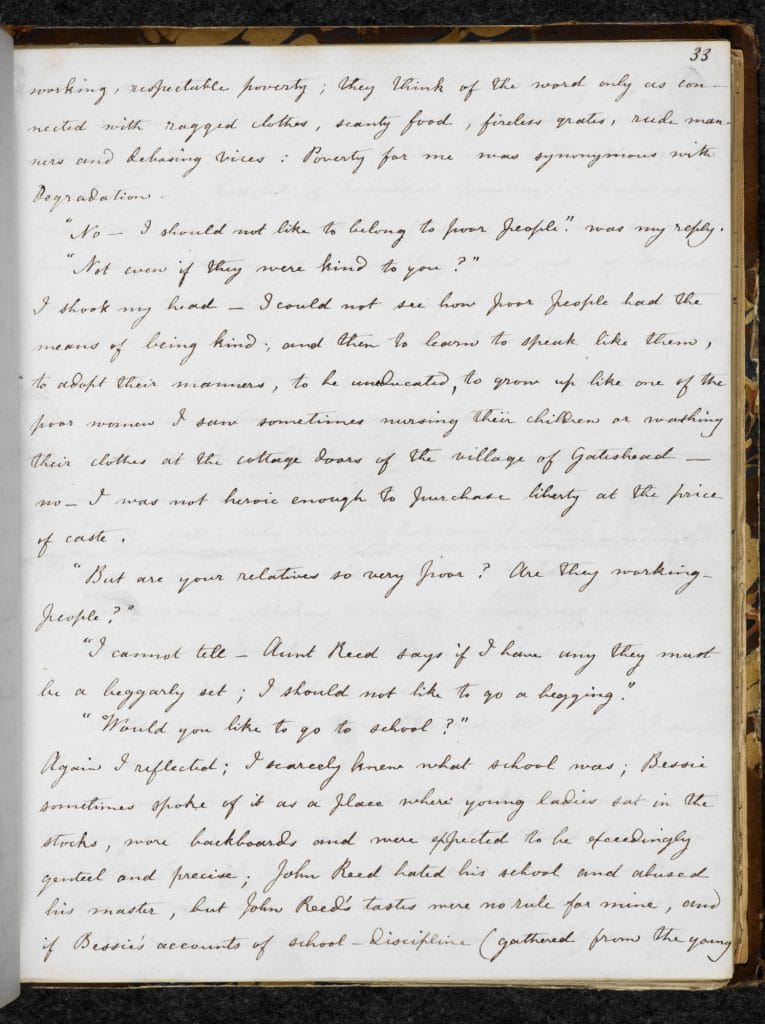

Life as a governess is the fate of Victorian fiction’s most famous female orphan, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Like many orphans of the time, Jane, whose parents died when she was very young, has been taken in by relatives. Pip in Great Expectations and Esther Summerson in Bleak House are similarly adopted by resentful and punitive relations. In Britain adoption was legally unregulated until the 1920s, so was easy and commonly informal. In George Eliot’s Silas Marner, the abandoned Eppie, whose mother dies at Silas’s door, is adopted by the solitary miser without any objection from the parish authorities. In Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, the young orphan Jude Fawley is taken in by his great-aunt. ‘It would ha’ been a blessing if Goddy-mighty had took thee too, wi’ thy mother and father, poor useless boy!’ she declares. Coming from a woman who likes to quote the Book of Job and ‘spoke tragically on the most trivial subject’, this seems comic, but to Jude it will later feel like prescience (ch. 2).

Institutions and defiance

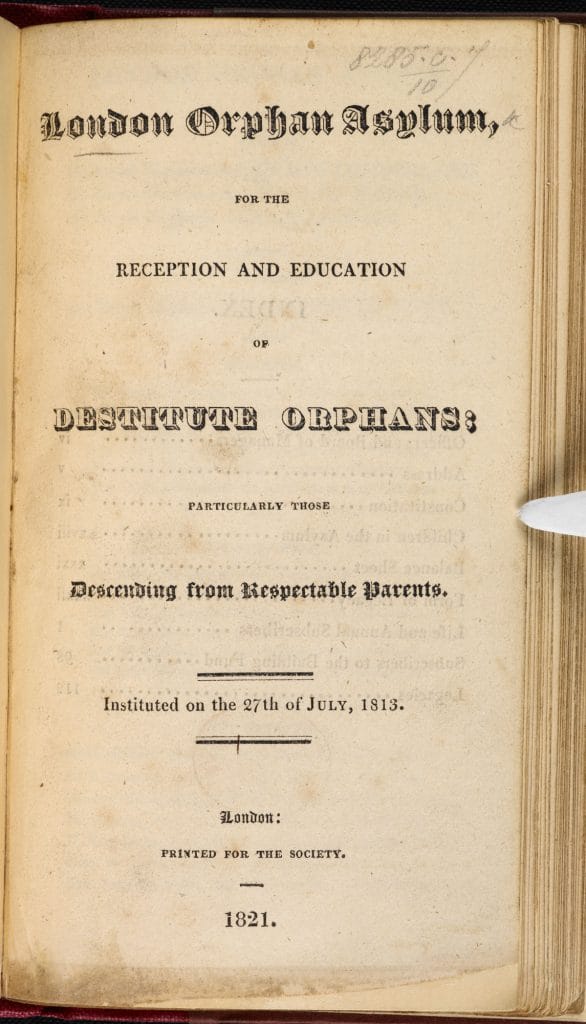

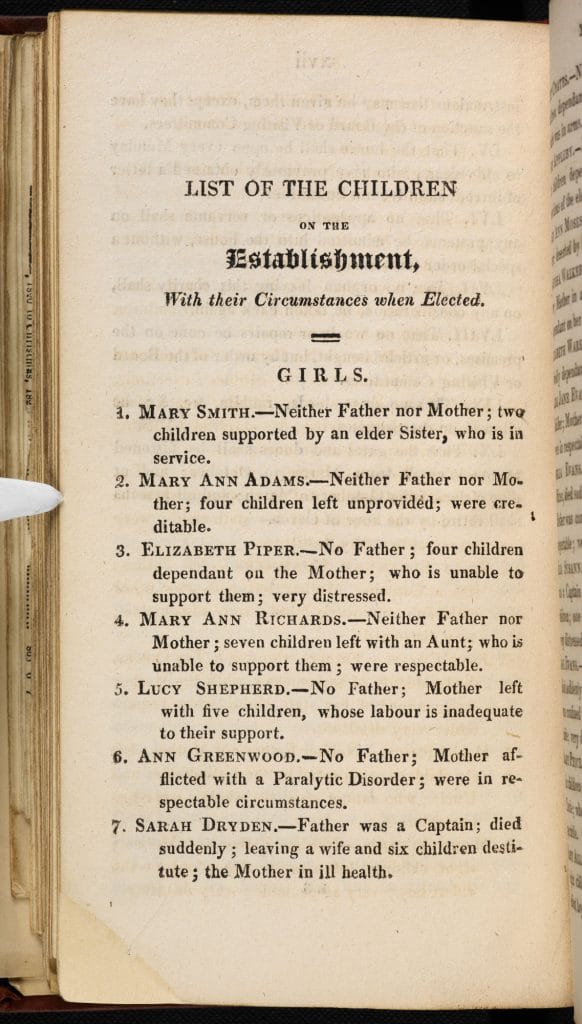

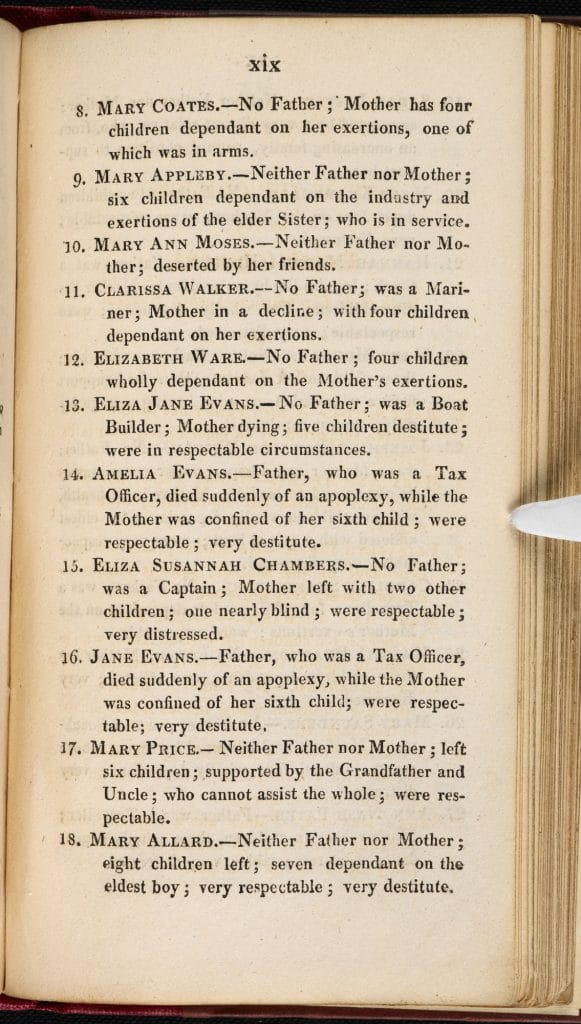

Jane Eyre is barely cared for by her unloving aunt, and is tormented by her cousins. She is then packed off to the appalling Lowood School, where most of the pupils are similarly abandoned. When she arrives she meets her fellow pupil Helen Burns, who tells her that ‘all the girls here have lost either one or both parents, and this is called an institution for educating orphans’ (ch. 5). Jane dubs the institution ‘the Orphan Asylum’, using a term that was common in the mid-19th century for institutions founded, like Lowood, by philanthropic donation and maintained by charitable donations. Mr. Brocklehurst, the self-proclaimed Christian who rules over the school, is malign and, as an orphan, Jane has only her own spirit with which to defend herself. Parentless protagonists like Jane and Jude are frighteningly vulnerable to prejudice and cruelty.

On her own in the world, Jane is eventually compelled to be a governess. Lucy Snowe, the heroine and narrator of Brontë’s final novel, Villette, also appears to be an orphan (though she is notoriously evasive about the particulars of her early life). She is forced to survive first of all as paid ‘companion’ to a cantankerous old lady, and then as a junior teacher in a girls’ school in Villette (a fictional version of Brussels). ‘I suppose you are nobody’s daughter’, comments her spoilt pupil Ginevra – and she is right (ch. 14). Brontë’s extraordinary explorations of female self-consciousness, featuring heroines who sometimes shocked contemporaries with their defiance and self-reliance, required her to orphan those heroines.

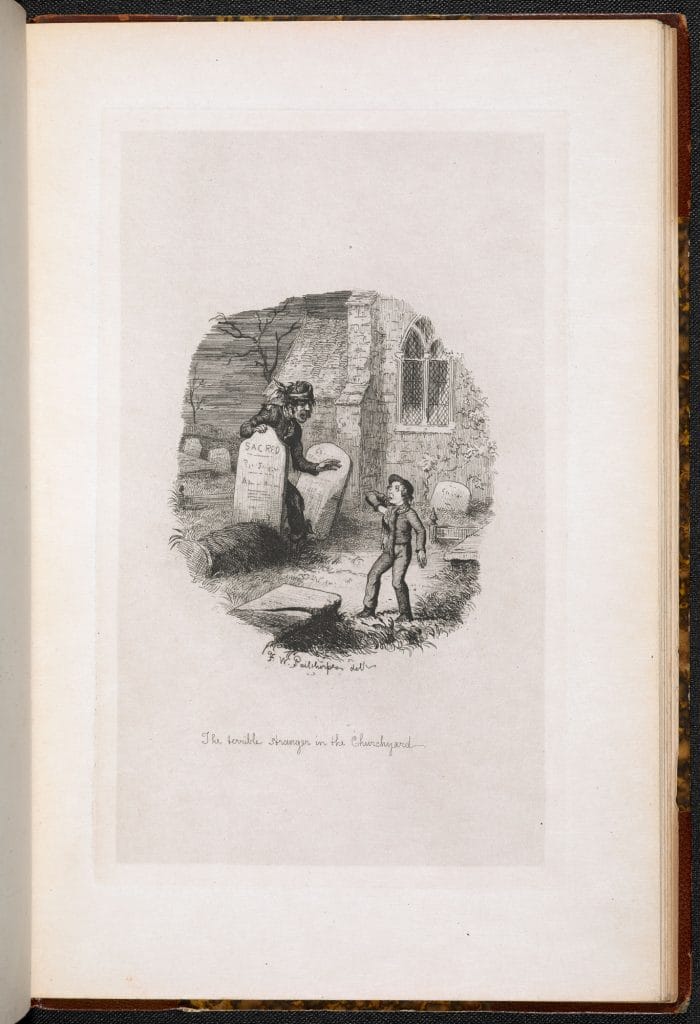

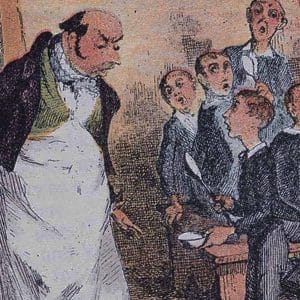

Even the fates of Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe seem less cruel than that of Dickens’s Oliver Twist. His unmarried mother dies immediately after giving birth to him in the parish workhouse, where, parentless, he must stay. The institution, maintained by local rates, is for the poor and destitute, but is the inevitable destination for orphans unfortunate enough not to have relations to adopt them. In the second chapter of the novel, Dickens reflects with savage facetiousness on the mortality rate among orphaned infants doomed to this fate.

Dickens’s orphans

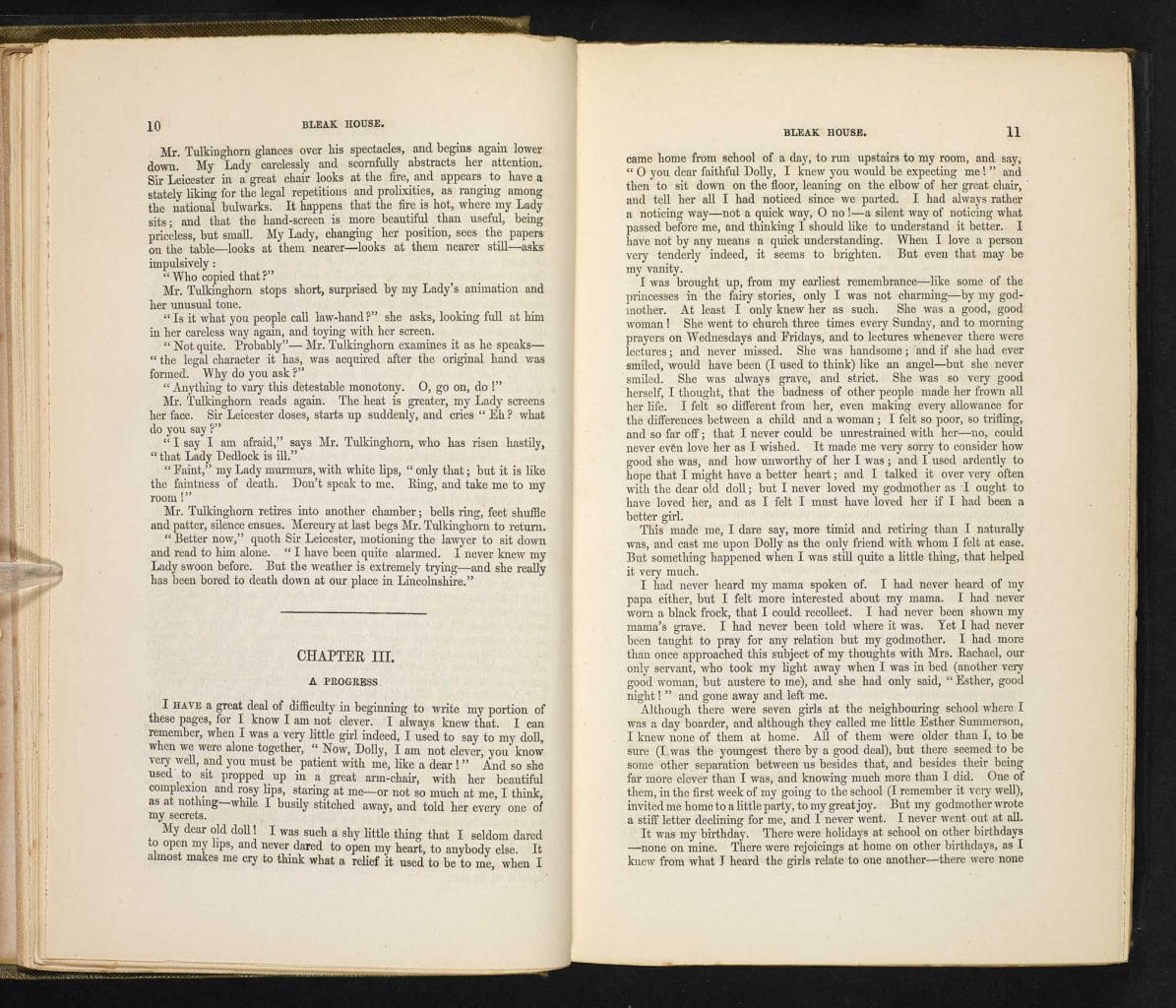

Dickens’s interest in orphans is almost obsessive. As well as Oliver Twist and Pip we have Martin Chuzzlewit and David Copperfield, Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities and Sloppy in Our Mutual Friend, among many others. Bleak House has a whole caste of orphans: not just Esther, the heroine, but also Richard Carstone, Ada Clare, his cousin, and Jo the crossing sweeper. Through these characters Dickens explores both heroic self-fashioning and feelings of abandonment, often combined. While Esther triumphs because of her inner resources – despite the baleful predictions of the ‘godmother’ (in fact her aunt) who brings her up – Richard, rudderless and self-deceiving, perishes. In the impoverished Jo, Dickens presents a sentimentalised version of the more likely condition of an orphan in the 19th century: a child abandoned to poverty, illiteracy and disease, whose premature death is inevitable.

Orphans have a special place in the history of the novel, especially in the 19th century. There is a real social history behind these fictional orphans. But orphaning your main characters was also fictionally useful – a means by which they were made to find their way in the world.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: John Mullan

John Mullan is Professor of English at University College London. John is a specialist in 18th-century literature and is at present writing the volume of the Oxford English Literary History that will cover the period from 1709 to 1784. He also has research interests in the 19th century, and in 2012 published his book What Matters in Jane Austen?