Foundlings, orphans and unmarried mothers

Ruth Richardson explores the world of poverty, high mortality, prejudice and charity that influenced the creation of Oliver Twist.

Children lacking one or both parents are a frequent theme in Charles Dickens‘s novels, which would not have surprised his Victorian readers because high mortality at the time meant that becoming an orphan was not a rare misfortune. You only have to think of Oliver Twist to see how Dickens used the predicament of the child alone in a rough world to reveal the drama and danger of the orphan’s plight. The nameless child could be anyone, and everyone.

What an excellent example of the power of dress, young Oliver Twist was! Wrapped in the blanket which had hitherto formed his only covering, he might have been the child of a nobleman or a beggar; it would have been hard for the haughtiest stranger to have assigned him his proper station in society. But now that he was enveloped in the old calico robes which had grown yellow in the same service, he was badged and ticketed, and fell into his place at once – a parish child – the orphan of a workhouse – the humble, half-starved drudge – to be cuffed and buffeted through the world – despised by all, and pitied by none. (Oliver Twist, Chapter 1)

His mother being at death’s door when she gave birth, Oliver is born without even a name in a workhouse. The only thing that could have helped identify him – her precious locket, which she had not pawned or sold despite being hungry and exhausted – is stolen from her corpse. Only late on in the story do we hear that it contained two locks of hair, and a wedding ring engraved with her name (Agnes). Local authorities sometimes advertised in newspapers when such a clue existed to a child’s parentage, in the hope that the woman’s family might recognise the information, ‘own’ the child as theirs, and save the parish the cost of rearing it.

Because his parentage was unknown and could not be discovered, Oliver’s name was bestowed upon him by the Parish Beadle, Mr Bumble, who explained that he had an alphabetical list of names ready for any child born in the parish in similar circumstances:

We name our fondlings in alphabetical order. The last was a S, – Swubble, I named him. This was a T, – Twist, I named him. The next one comes will be Unwin, and the next Vilkins. I have got names ready made to the end of the alphabet, and all the way through it again, when we come to Z.

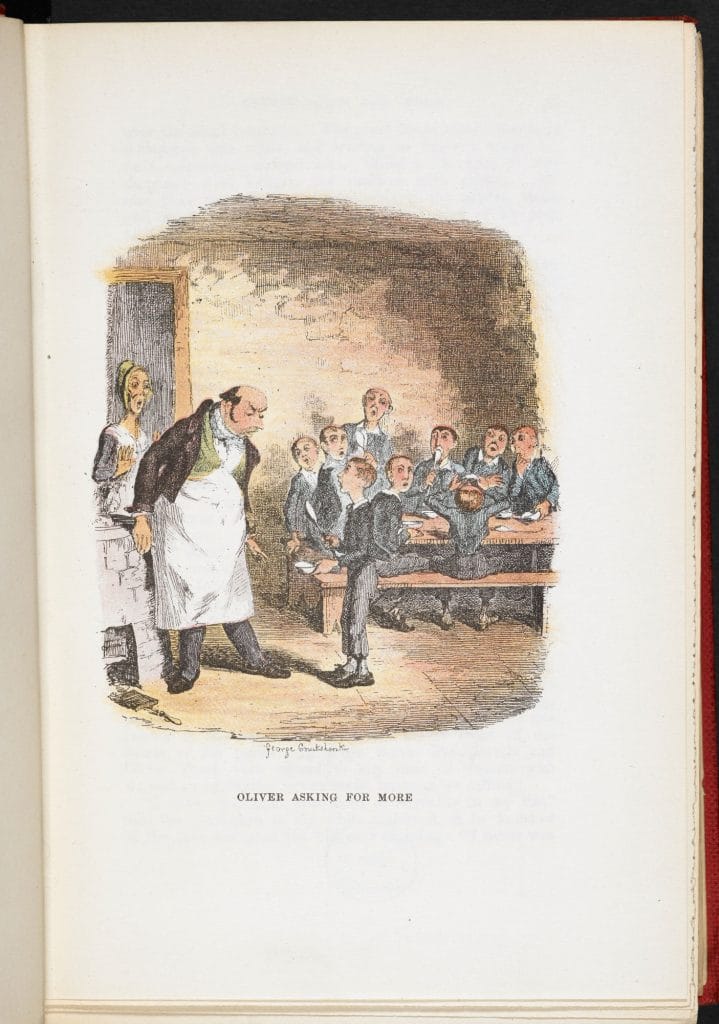

Mr Bumble’s slip – referring to ‘fondlings’ instead of ‘foundlings’ might suggest that the children are well cared for, but, as we know from the novel, in Oliver’s case, they were not. When he famously went up to ask for more food, it was because Oliver and the other workhouse boys were so hungry that one of them had threatened to eat another boy if he got no more to eat. The boys had cast lots to see who would go up and ask for second helpings, as they knew that whoever did the asking would be severely punished for their temerity.

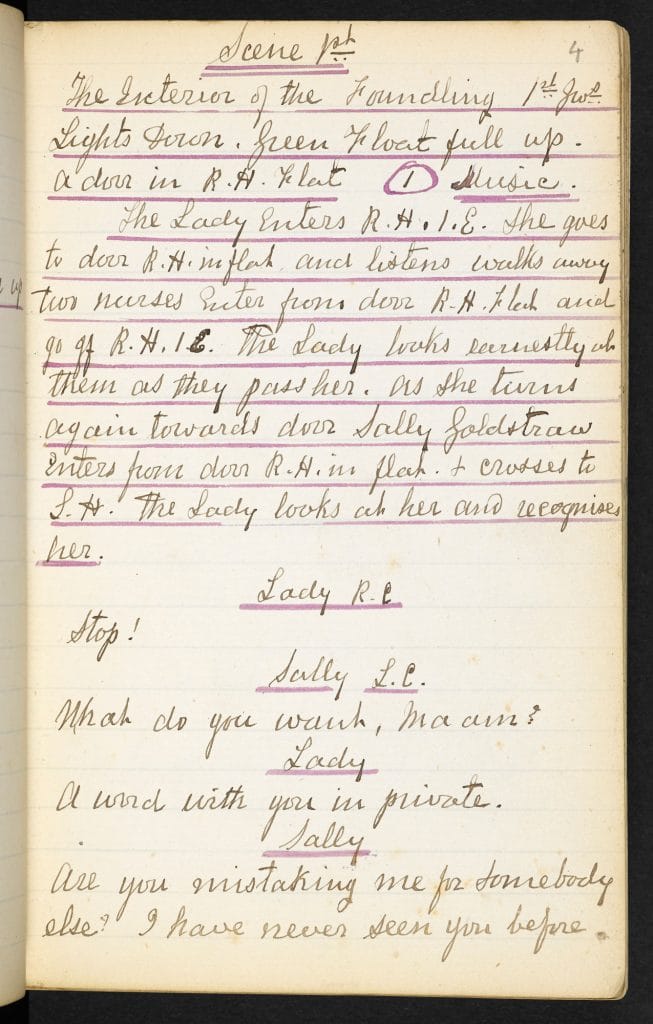

The Foundling Hospital

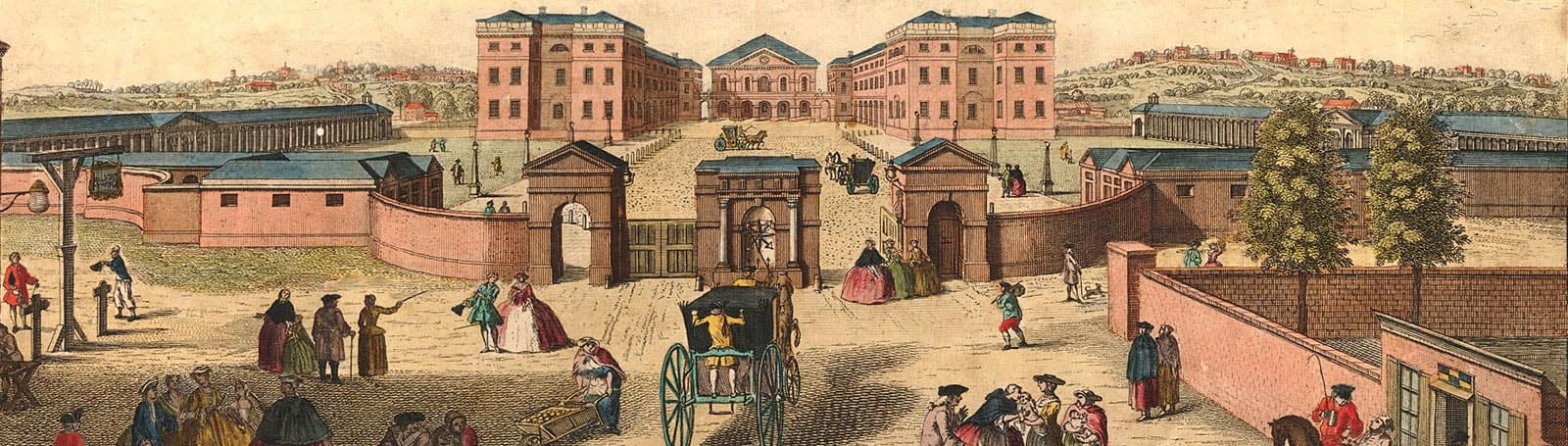

In fact, at the Foundling Hospital the same kind of naming custom was observed. The ‘Hospital’ (offering hospitality) was a very famous London institution, founded in the 1740s by an old sea-captain called Thomas Coram, as a home for deserted children. Coram had been very distressed by knowledge of the large numbers of unwanted children that were found on doorsteps or under bushes, sometimes dead from exposure because found too late. His idea was for a charitable institution that would take in these unwanted children, and care for them until they were of an age to fend for themselves. All children taken in as foundlings – even those whose names were known – were given entirely new identities at the outset. The Hospital provided shelter, food, clothing, medical care, education, and work-placements so its children were well-equipped to cope out in the world.

That great institution occupied a large tract of land very close to Doughty Street, where Dickens and his young family were living while he was finishing Oliver Twist. The Hospital was an impressive building, and it served as a model for the care of foundlings in other places. The site of the Hospital is now a park, Coram’s Fields, to the south of the British Library.

On Sundays, Dickens used to worship in the Foundling Chapel with his family, and he used the name of the Charity’s Secretary, Mr Brownlow, for a kindly and important character in his novel. The real Mr Brownlow is an interesting figure – he worked as the Secretary of the Foundling Hospital for an extraordinary 58 years, and was originally in fact a foundling himself. His surname was taken from that of the owner of the land on which the Hospital stood. Mr Brownlow wrote the history of the institution and the life-histories of some famous foundlings, and copies of his books are held in the British Library. In Oliver Twist, Mr Brownlow is a very kindly elderly gentleman, who is the victim of pocket-picking by the Artful Dodger. He saves Oliver from prison, and tries to protect him from the book’s villains Fagin and Bill Sykes.

Unmarried mothers

In Oliver Twist, Oliver’s mother is a single woman, an unmarried mother. To introduce such a subject in a novel was unusual in the 1830s, and it is likely that the basis of Dickens’s story would have shocked some readers. To become pregnant before being married was regarded as a source of shame for a woman in the early Victorian era, and in the novel Oliver’s mother left home so that her family did not suffer from her disgrace. The stigma did not apply to unmarried fathers. We find out later in the story that Oliver’s father was already married, but unhappily so, when he had met Oliver’s future mother. In those days ordinary people could not obtain divorces, so there were many unhappy marriages, many secret relationships. No contraception was available, so pregnancy was often an outcome. Oliver’s father died abroad before the couple knew there was a child on the way, so Oliver’s mother was left – like so many women – to face her future alone.

Surviving financially in the world was extremely difficult for an unmarried mother, with a child to care for. Women’s wages were half of what men would receive for the same work. The kind of work usually available to women, such as needlework, was very poorly paid.

A child born outside marriage, or ‘out of wedlock’, was regarded as ‘illegitimate’, without full legal status, and this was a serious stigma until the mid-20th century. It was recognised in the 19th century that illegitimate children were half as likely to survive compared to children with married parents. They and their mothers were victims of discrimination.

Few employers would take on a woman with an illegitimate child as a regular worker, partly because childcare distracts a mother, and partly because of the shame of illegitimacy. London was full of poor people seeking work, and without some useful skill, it was hard to find. With a child to care for, it was extremely difficult to make enough money to survive. Images of ballad singers begging on the streets – known as the lowest kind of ‘work’ – often show a woman with baby to care for. Many unwed mothers, or widows with small children, ended up like Oliver’s mother: without a home, in poor health, hungry and exhausted, before they would apply to enter the last place of refuge for the desperate: the workhouse. There, such women would be expected to undertake some of the drudgery of the institution. These women were singled out in some places by having to wear a special uniform which drew attention to their status as unmarried mothers. Some women became institutionalised and ended up as pauper nurses, others might leave their child in the institution, to try to make a new life outside. Like many women, Oliver’s poor mother was too weak when she gave birth, and died, leaving him alone in the world.

In some ways, being a foundling could perhaps be regarded as a preferable position in the world than being an illegitimate parish orphan, just as it was more fortunate for a baby to be taken in by the Foundling Hospital than the local workhouse. The 18th century novelist Henry Fielding’s famous character Tom Jones was a foundling, who turned out to be the illegitimate child of a good family. Dickens was an admirer of Fielding’s novels, and it seems the predicament of his own leading character, Oliver Twist, shows what might happen to a child in a similar predicament, in a later era. In the end he, too, turns out to have come from a comfortable family. Both discoveries make for happy endings in these books, but of course real life was not always so promising.

The text in the article is © Dr Ruth Richardson. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Ruth Richardson

Ruth Richardson is an independent scholar, a Visiting Fellow at King’s College London and Visiting Professor at Hong Kong University. A devoted reader in the British Library’s Rare Books Room, she is the author/editor of several books including Death, Dissection and the Destitute, Vintage Papers from the Lancet, Medical Humanities, The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy and most recently, Dickens and the Workhouse. She has published many papers in learned journals, created online exhibitions for King’s College Special Collections and for the Bishopsgate Institute, and is a frequent contributor to The Lancet. She is currently working on a study of marginalia and topography in Dickens and Tennyson, and working to preserve the Cleveland Street Workhouse.