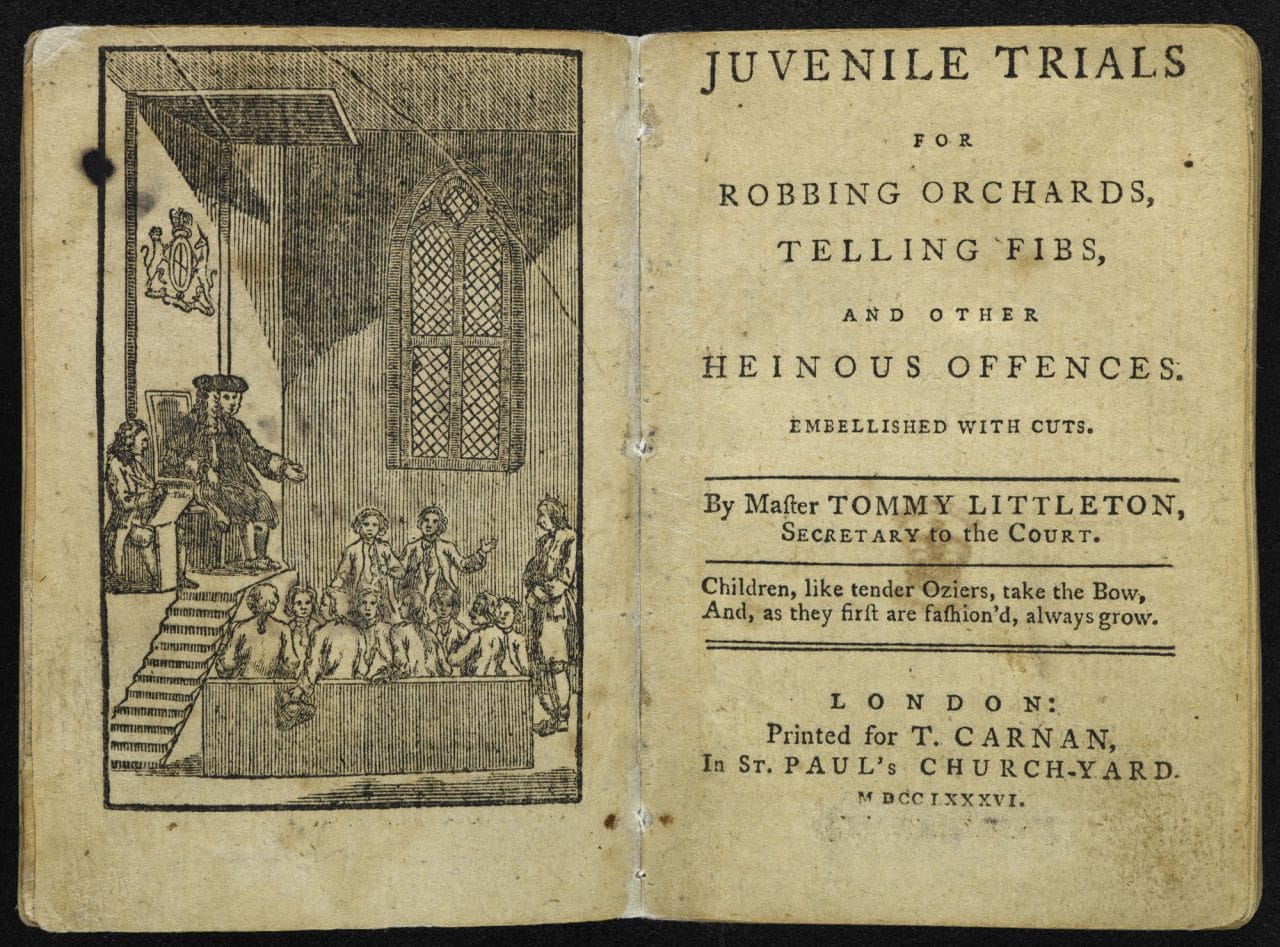

Juvenile crime in the 19th century

Novels such as Oliver Twist have made Victorian child-thieves familiar to us, but to what extent did juvenile crime actually exist in the 19th century? Drawing on contemporary accounts and printed ephemera, Dr Matthew White uncovers the facts behind the fiction.

The success of Oliver Twist owes much to the biting satire and keen social observations contained within its pages. The misery of workhouses, the morally corrosive effects of poverty and the degradation of life in Victorian slums all received Dickens’s close attention. The novel’s prominent theme though is criminality, witnessed most vividly in the activities of Fagin’s gang of nimble-fingered child-thieves. But how realistic was Dickens’s portrayal of criminality among Victorian boys and girls?

Popular fears

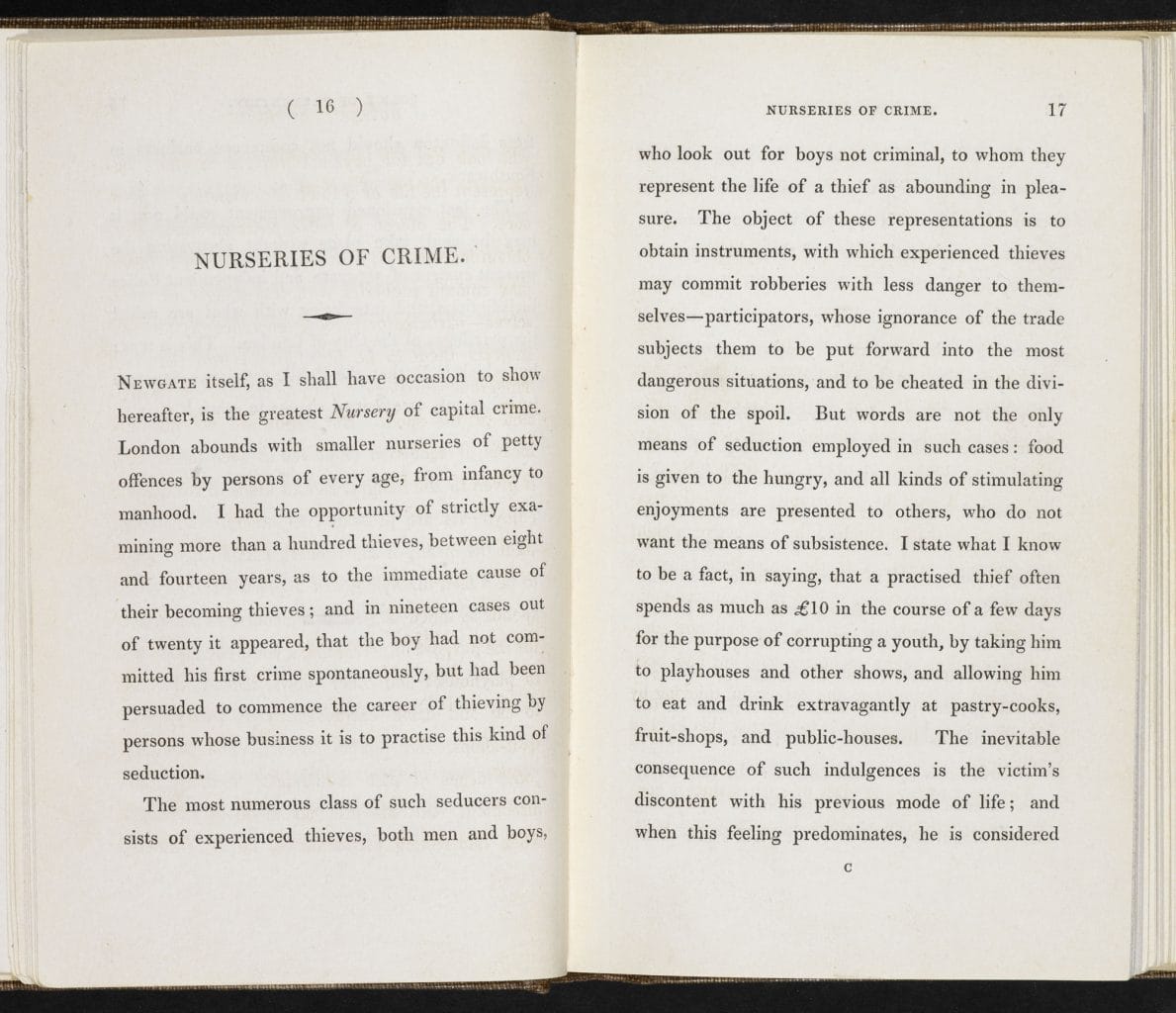

Although youth crime had been a concern since the 1700s, a decline in formal apprenticeships, and the disruptive effects of industrialisation on family life after 1800, did much to create fears among the general public about the activities of criminal gangs of boys and girls in London and elsewhere.

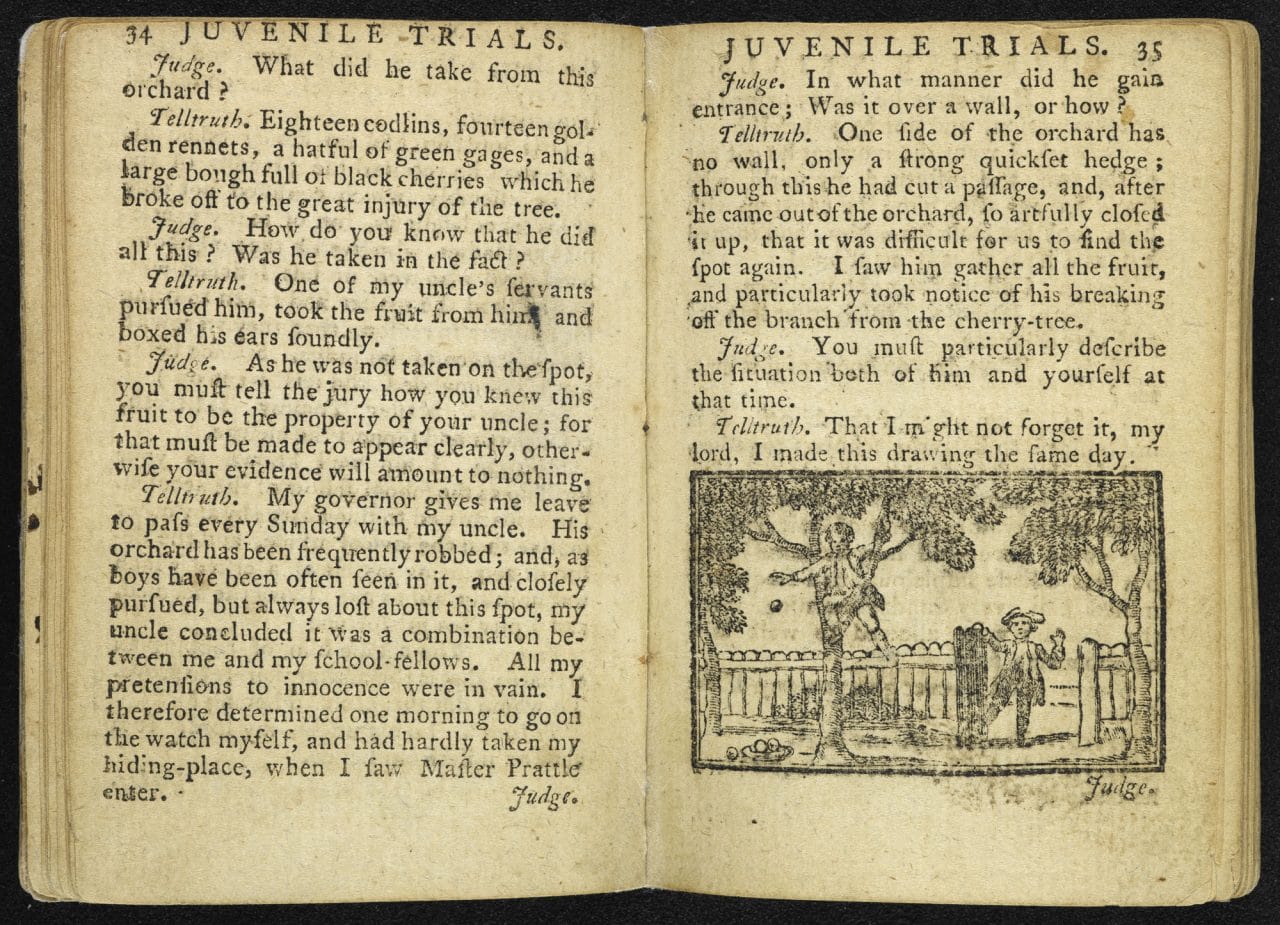

Sensational stories of crime and violence filled the pages of the popular press after 1800 with details of juvenile crime appearing in newspapers, broadsides and pamphlets. The activities of so-called ‘lads-men’ were regularly reported. These were criminal bosses who supposedly trained young boys to steal and then later sold on the stolen goods they received from them. Thomas Duggin for example was an infamous ‘thief-trainer’ who worked in London’s notorious St Giles slum in 1817, and as late as 1855 The Times newspaper reported the activities of Charles King, a man who ran a gang of professional pick-pockets. Among King’s gang was a 13-year-old boy named John Reeves, who stole over £100 worth of property in one week alone.[1] Similarly, Isaac ‘Ikey’ Solomon was a well-known receiver of stolen goods in the 1810s and 1820s who was arrested several times, and on one occasion escaped from custody. Solomon gained notoriety for being a trainer of young thieves and was for some time (incorrectly) considered to be the inspiration behind Dickens’s character of Fagin owing to his similar Jewish heritage.

‘Flash-houses’ also received regular attention from the police during the first half of the century. These were pubs or lodging houses where stolen property was ‘fenced’, and were considered by the police and magistrates to be ‘nurseries of crime’.[2] One report in 1817 described flash-houses as containing ‘distinct parties or gangs’ of young boys, while later in 1837 a police witness recalled how one lodging house in London had ‘20 boys and ten girls under the age of 16’ living together, most of whom were ‘encouraged in picking pockets’ by their ‘captain’.[3]

Child crime: fact or fiction?

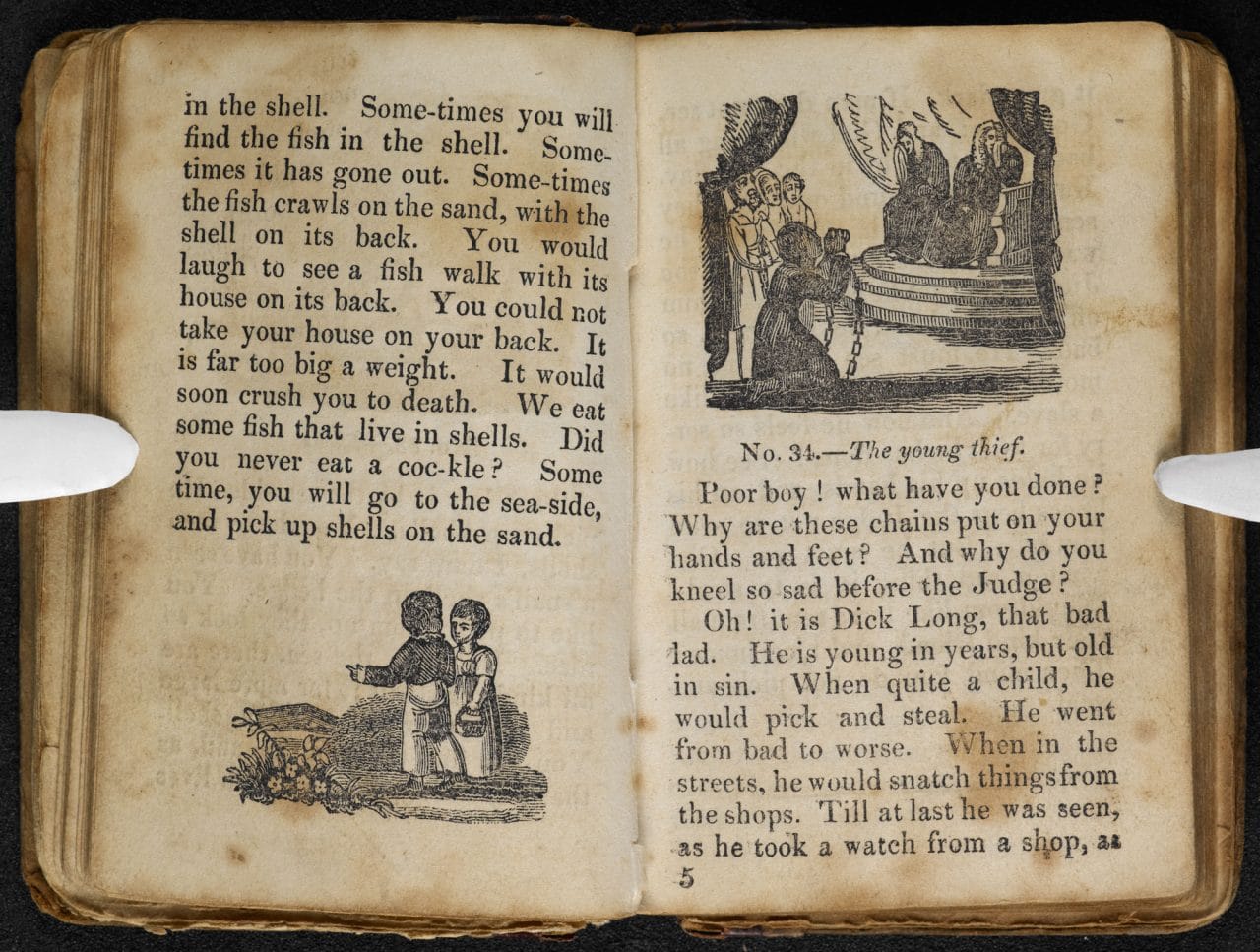

Evidence from the courts and newspaper articles during the first half of the 19th century suggests that juvenile crime was indeed a genuine problem. Picking of pockets was especially troublesome, particularly the theft of silk handkerchiefs, which had a relatively high resale value and could thus be easily sold. Field Lane in London for example (the setting of Fagin’s den in Oliver Twist) was the home to several notorious receivers of stolen goods, where it was believed more than 5,000 handkerchiefs were handled each week. Often these were hung on poles outside the shops for sale to passers-by, many of whom went there to buy back their own stolen property.

Crowded places such as fairs, marketplaces and public executions were particularly profitable for young thieves. In 1824 for example a 15-year-old boy, Joseph Mee, was charged with picking-pockets at a public execution taking place at the Old Bailey; a youth described by the magistrate as a ‘hardened and unconcerned’ offender.[4] At Greenwich Fair in 1835 13-year-old Robert Spencer was caught by a policeman drawing a handkerchief from the pocket of a gentleman in the crowd, while later in 1840 another constable stated in court how he witnessed 11-year-old Martin Gavan and another boy ‘try several pockets’ before stealing a gentleman’s handkerchief among a crowd that had gathered around a traffic accident.[5]

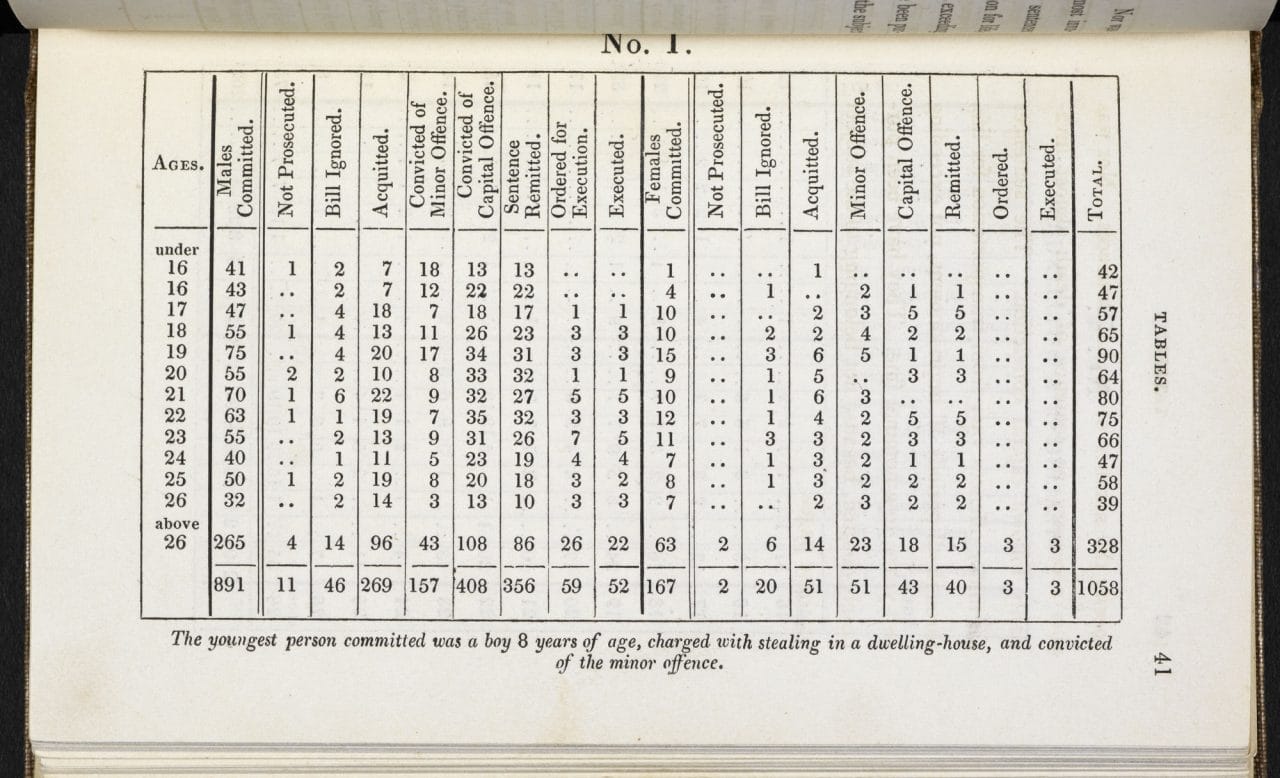

Around three in every four petty thefts of personal property recorded in the county of Middlesex in the first quarter of the 19th century were committed by people under 25 years old, the vast majority of whom were teenagers or younger boys.[6] Between 1830 and 1860, over half of all defendants tried at the Old Bailey for picking pockets were younger than 20 years of age.[7]

This evidence is further supported by the findings of social investigators at work during the 19th century. Journalist Henry Mayhew, for example, wrote extensively about the corrupting effects of poverty on the young. In London Labour and the London Poor Mayhew described life in the capital’s ‘low-lodging houses’, where he found several young boys engaged in daily petty thefts, including one who recounted how he was regularly drunk at the age of 10. Mayhew also described the activities of ‘Mudlarks’: boys and girls aged between eight and 15, who plundered goods from barges moored on the River Thames.

However, historians have debated the true extent of juvenile crime in the 19th century. Changes in the way that children could be prosecuted after 1847, more sophisticated ways of gathering statistics and an over-emphasis on child criminality by moral reformers may have contributed to an exaggeration of an assumed increase in ‘juvenile delinquency’.

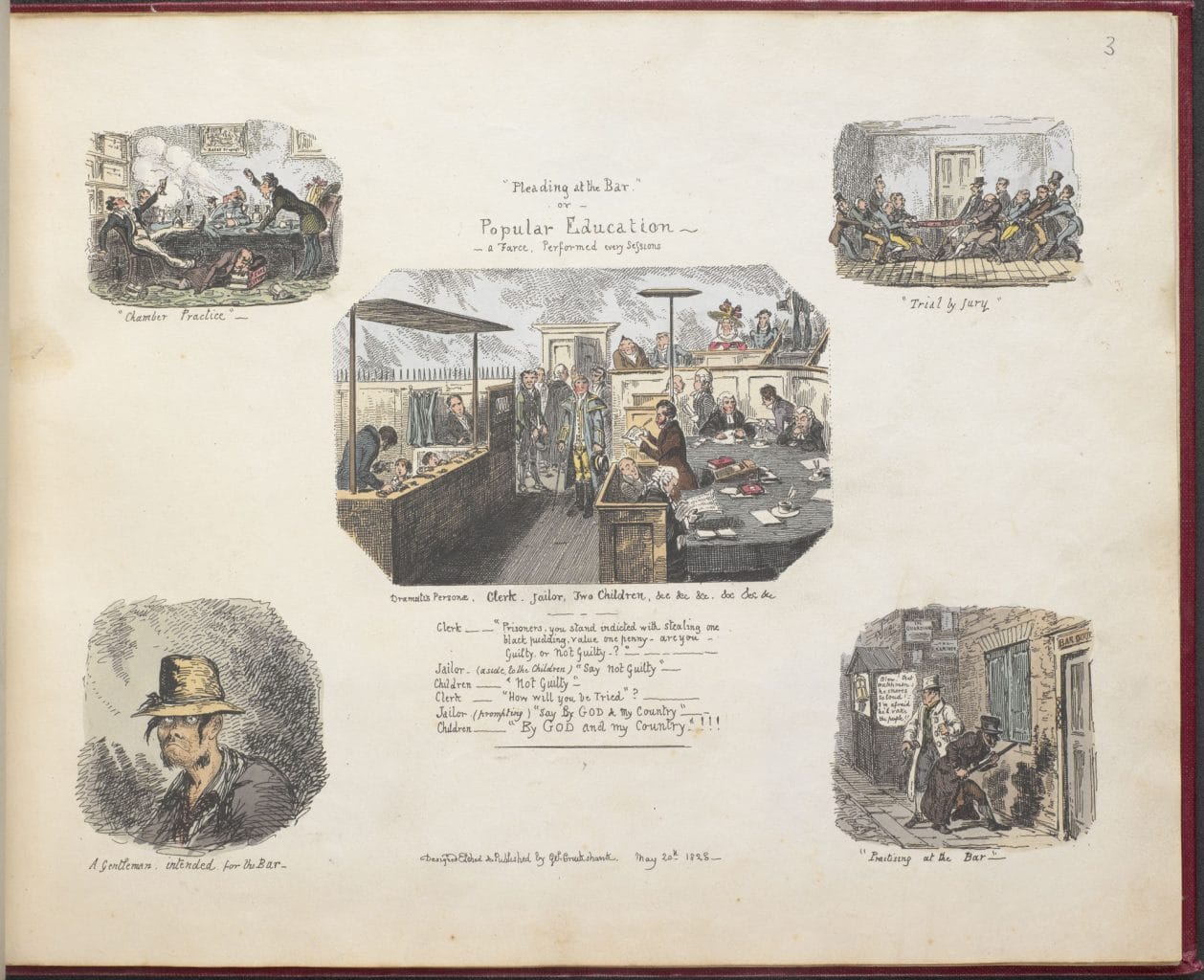

Prosecution and punishment

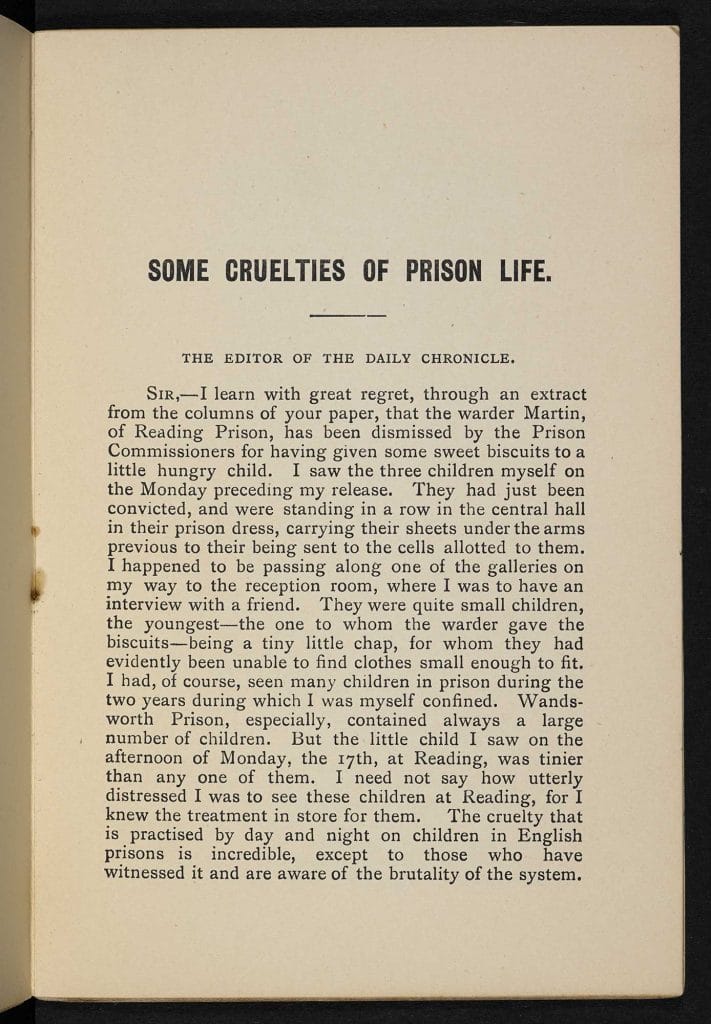

To modern eyes the treatment of juvenile criminals in the 19th century appears particularly savage. After 1800 children between the ages of seven and 14 were considered incapable of forming criminal intentions, but could nevertheless be found guilty where this was proven beyond doubt. In theory, children convicted of serious felonies therefore faced the full penalty of the law: namely sentences of imprisonment, transportation and death.

In reality, death sentences bestowed on children were almost always commuted to lesser sentences on the grounds of leniency. Of the 103 children aged 14 or under who were sentenced to death at the Old Bailey between 1801 and 1836, not one was executed. Typically, when two 13-year-olds and a 12-year-old were convicted of a burglary in 1821, they were ‘recommended to mercy on account of their youth’: a phrase that was regularly recorded by the courts.[8] The last execution of a juvenile in England was probably that of John ‘Any Bird’ Bell, at Maidstone in Kent in 1831: a 14-year-old who committed a cold blooded murder of a 12-year-old boy during a bungled robbery . His sentence by this time was already considered exceptional.[9]

Death sentences for girls and boys under 16 years of age were in practice usually commuted to transportation. By the 1830s, each year around 5,000 prisoners, some of whom were as young as 10, were carried by ship to penal colonies in Australia, to serve sentences of seven or 14 years (and occasionally life). Once safely arrived, the convicts were set to work on public projects (such as building harbours or prisons) or were otherwise given manual tasks as servants to private employers, all of which (it was hoped) would help reform the offenders. Transportation was finally abolished in 1857 following concerns about the deterrent effect of the sentence on would-be criminals.

Alternative punishment options were regularly used to deal with child criminals. Whipping or flogging for example was frequently used until the end of the century. Whippings could be carried out quickly after guilty sentences were passed in court, or otherwise took place in prisons as part of custodial sentences. In the 1860s, the whipping of boys at Bow Street magistrates’ court was abandoned as (according to a former magistrate) ‘the screams of the boys’ caused ‘angry excitement’ among nearby residents.[10] Children also served lengthy prison sentences, normally alongside hardened adult offenders.

脚注

- The equivalent of around £8000 in today’s money.

- Heather Shore, Artful Dodgers. Youth and Crime in Early Nineteenth-Century London (London: Royal Historical Society, 1999), p. 24. (This is Heather Shore’s paraphrase though the term was being used commonly by the mid nineteenth century).

- First Report from the Committee on the State of the Police of the Metropolis (London, 1817), p. 429; The Times, 28 June 1837.

- The Times, 1 December 1824.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.1, 15 February 2014) May 1835, trial of Robert Spencer (t18350511-1325) [accessed 1 April 2014]; Old Bailey Proceedings Online, March 1840, trial of Martin Gavan (t18400303-902) [accessed 1 April 2014]

- Heather Shore, Artful Dodgers. Youth and Crime in Early Nineteenth-Century London (London: Royal Historical Society, 1999), p. 59.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online, Tabulating defendant age where offence category is pocketpicking, defendant age is at least 1 and defendant age is at most 80, between January 1830 and 1860. Counting by defendant [accessed 1 April 2014]

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online, April 1821, trial of James Jordan, William Donald, Thomas Steers (t18210411-20) [accessed 1 April 2014]

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online, April 1821, trial of James Jordan, William Donald, Thomas Steers (t18210411-20) [accessed 1 April 2014]

- The National Archives, HO 45/7550. Also quoted in L. Radzinowicz and R. Hood, A History of English Criminal Law and its Administration from 1750. Volume 5: The Emergence of Penal Policy (London: Stevens, 1986), p. 715.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Matthew White

Dr Matthew White is Research Fellow in History at the University of Hertfordshire where he specialises in the social history of London during the 18th and 19th centuries. Matthew’s major research interests include the history of crime, punishment and policing, and the social impact of urbanisation. His most recently published work has looked at changing modes of public justice in the 18th and 19th centuries with particular reference to the part played by crowds at executions and other judicial punishments.