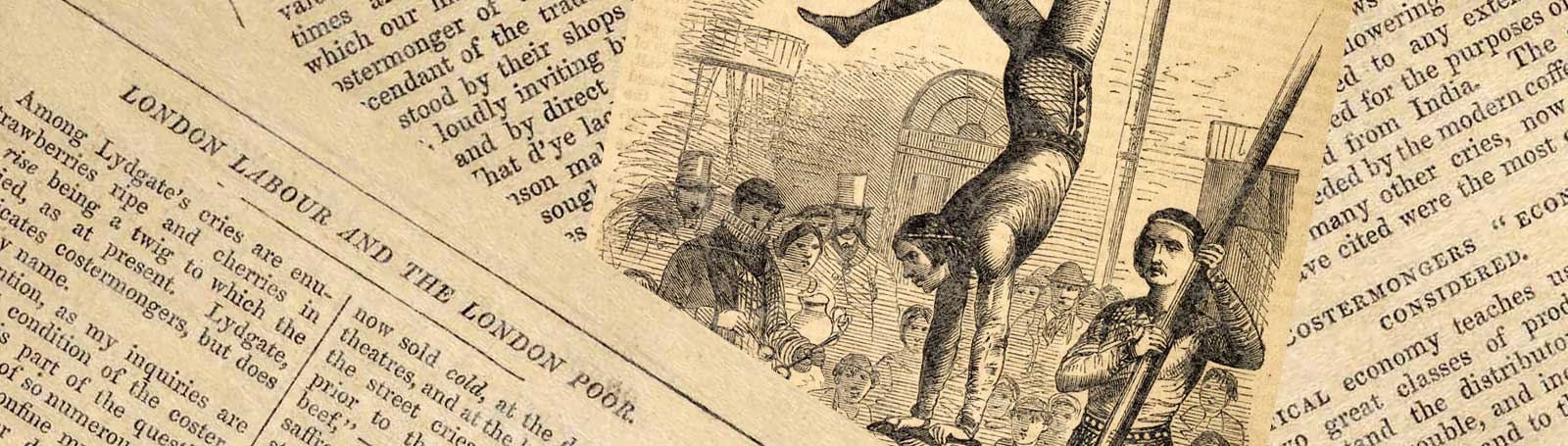

Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor

出版日期: 1851 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Investigative Journalism

London Labour and the London Poor is a vivid oral account of London life in the mid-19th century. In his introduction to the work, writer and editor Henry Mayhew writes: ‘I shall consider the whole of the metropolitan poor under three separate phases, according as they will work, they can’t work, and they won’t work’. Thus, the book proceeds from interviews with working-class professionals (dockers, factory workers) to street performers and river scavengers (‘mudlarks’ ) and finally to interviews with beggars, prostitutes and pickpockets. The completed four-volume work amounts to some two million words: an exhaustive anecdotal report on almost every aspect of working life in London.

Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor by Mary L Shannon

‘A picture of human life so wonderful, so awful … so exciting and terrible’[1]: this is how the novelist and journalist W M Thackeray described Henry Mayhew’s accounts of the lives of the poor in Victorian London. Mayhew wrote his articles, collected together as London Labour and the London Poor (1851), in the decades that Dickens wrote Dombey and Son and Bleak House, and Mayhew’s work is every bit as vivid and surprising as a Dickens novel. Instead of simply describing the London poor, Mayhew lets them speak to the reader directly in their own words and their own voices, albeit edited by Mayhew the middle-class journalist. They jump off the page, opinionated and alive.

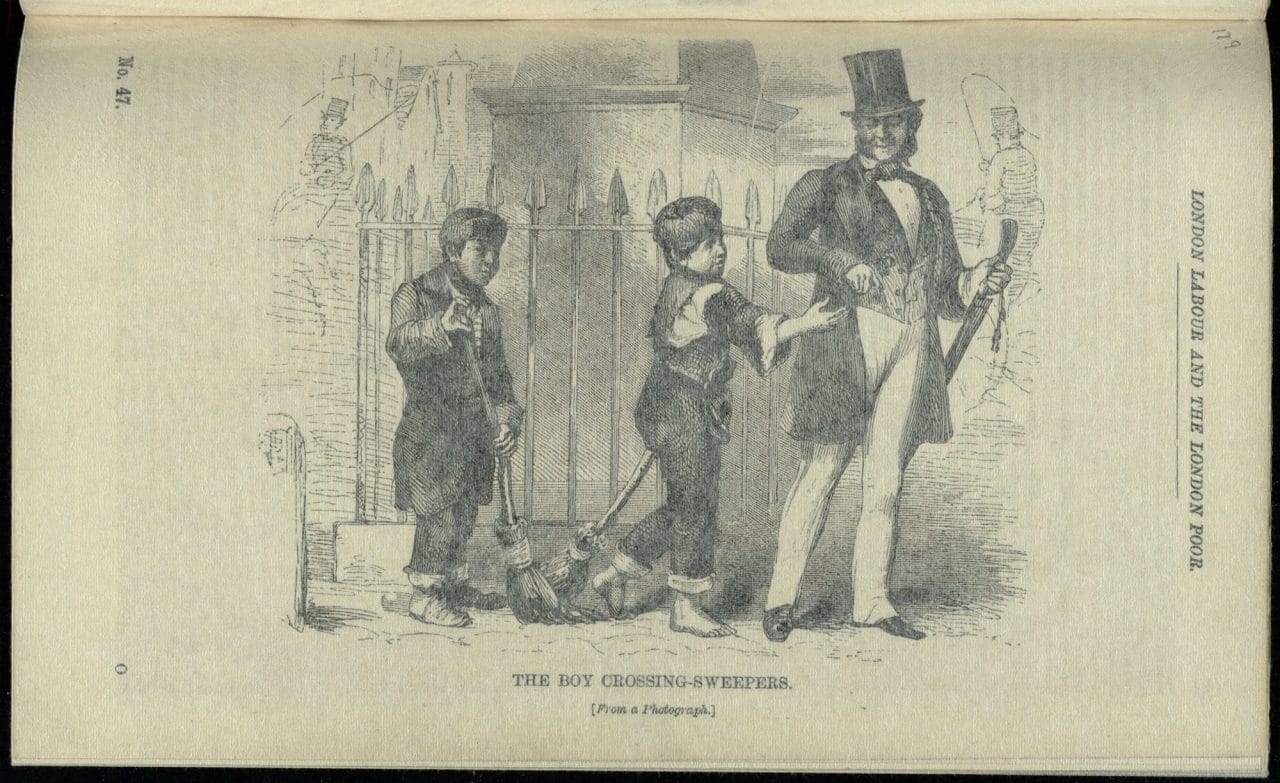

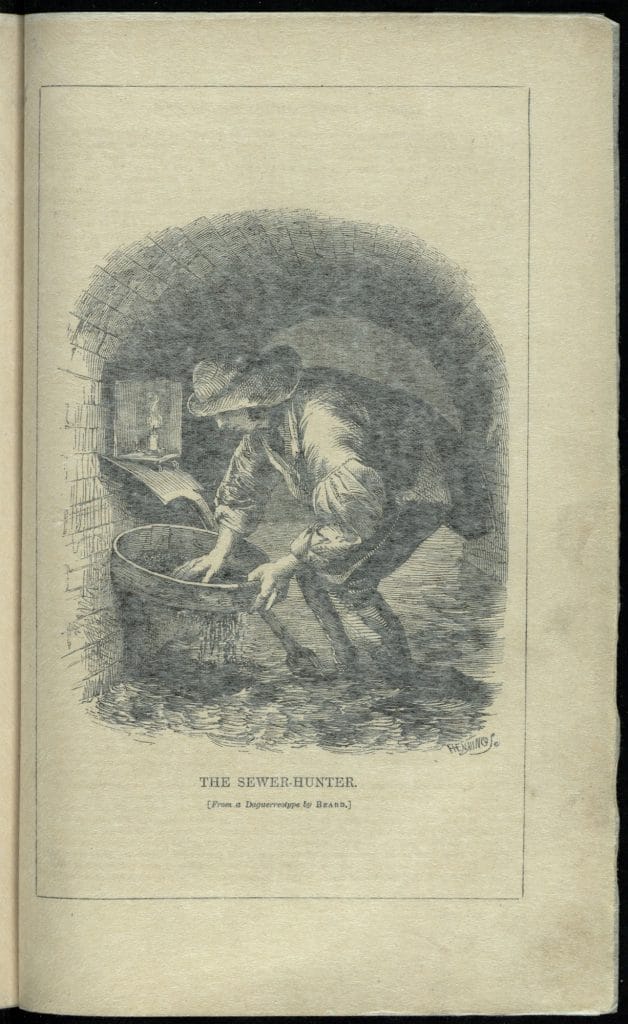

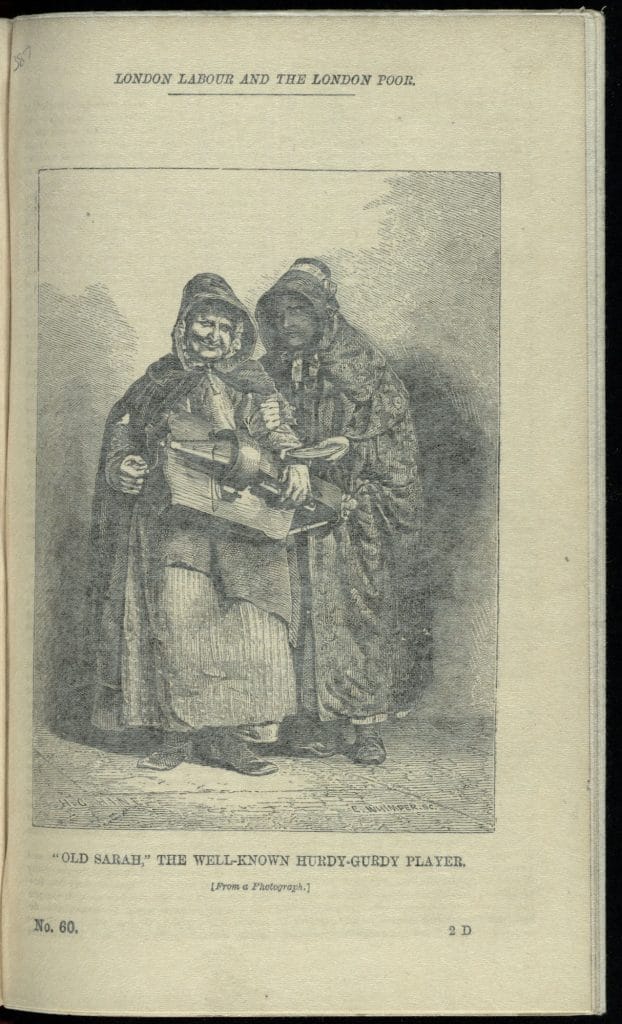

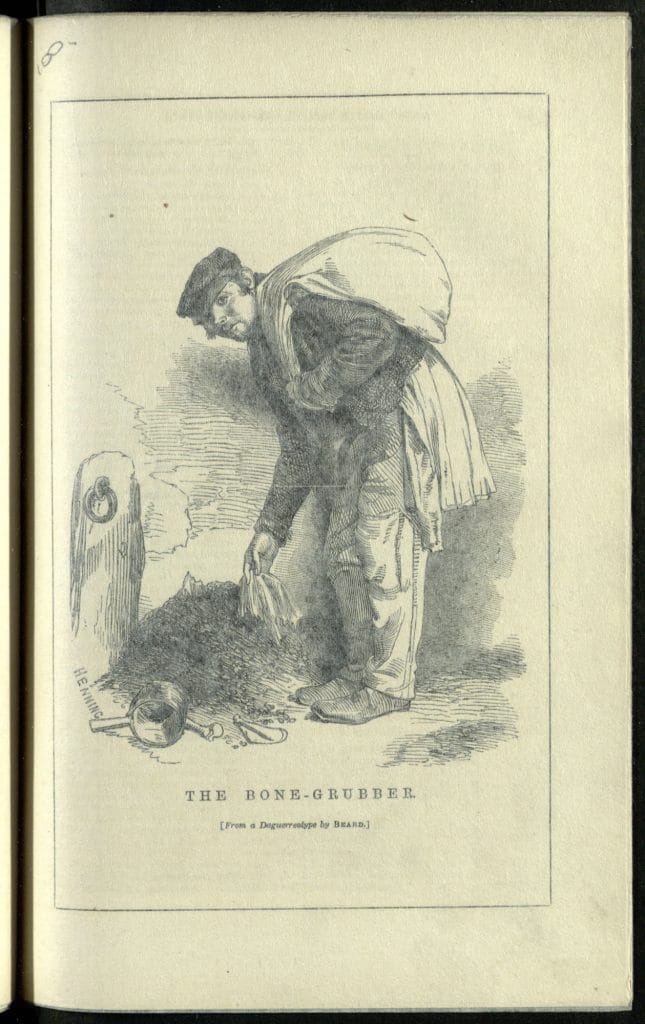

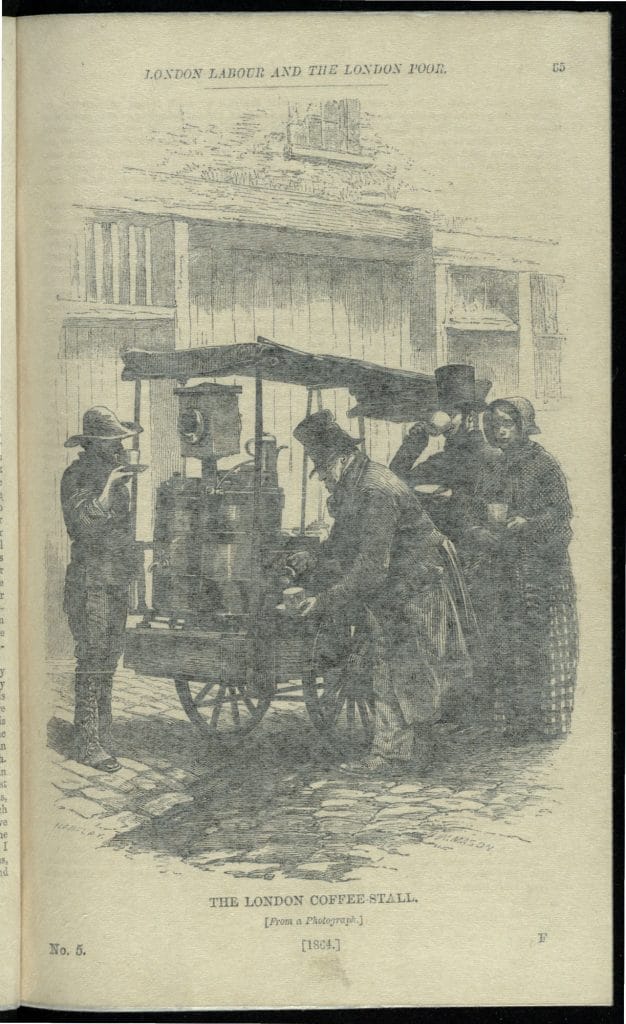

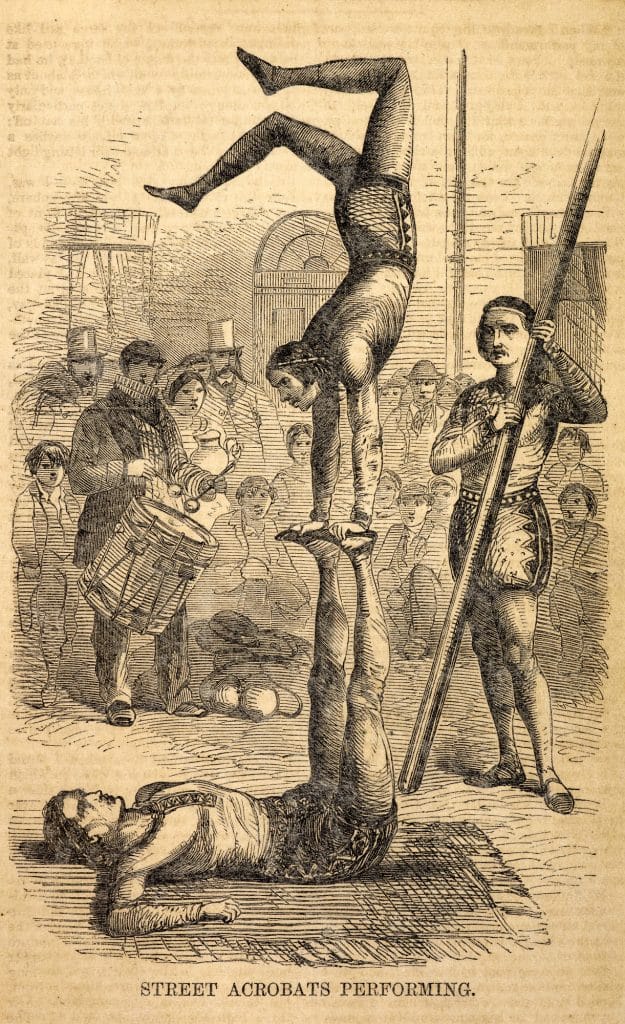

These accounts are drawn from his interviews with the London poor, either in the street, at his office, in their homes, or (as word of his work spread) conducted after specially arranged meetings of large groups of poor workers. Mayhew made use of the latest technology to bring his work to life: accompanying the text are engravings copied from daguerreotypes, an early form of photography. Mayhew aimed to cover all the poor of London, but this proved too much work. What we have, then, is interviews with the poor street-sellers and street-scavengers of London, and an extra volume with work by other contributors on London’s criminal underworld

London street-sellers

Mayhew’s interviewees were out in the London streets in all weathers, carrying out all kinds of work in tough conditions and for barely any money. Some trades we are familiar with today: the coffee-stall keepers; the street-musicians busking for coins; the stall holders selling anything from saucepans to pictures, bootlaces to umbrellas. Some worked at the street markets where the poor bought their Sunday dinner, and some just walked around the city and sold their scanty stock in the streets. We meet street-sellers of tea and rat-poison, dog-collars and jewellery, paper and ballads. Mayhew interviews a man who sells pamphlets that he pretends are ‘indecent’, and another who sells printed accounts of the latest ‘murders, seductions, … explosions, alarming accidents, [and] duels’. Those who sold fruit, meat and vegetables in the streets were known as costermongers, and Mayhew spends the beginning of London Labour and the London Poor telling us all about them. They sold eels, mackerel, herrings, apples, oranges, cherries, grapes, walnuts, turnips, onions and cabbages. They told Mayhew all their tricks for selling rotten meat or fruit disguised as fresh food: they boiled oranges to make them look bigger and juicier; filled up baskets with leaves and put strawberries on top so customers thought they were buying baskets full of fruit; and hid rotting fish amongst fresh fish.

A penny a bunch – hurrah for free trade!

Here’s your turnips! Fine ‘ating apples

Who’ll buy a bonnet for fourpence?

Buy, buy, buy, buy, buy, – bu-u-uy!

Some unpleasant occupations

The costermongers had relatively easy lives compared with the rag-gatherers, the bone-gatherers and cigar-end finders (who hunted for rubbish in the street to sell on). Other people driven to unpleasant occupations in a desperate bid to survive were the mudlarks (mostly old women and children who scavenged in the mud and sewage at the edge of the River Thames for anything they could sell), the crossing-sweepers (who swept the streets clear of mud and dung so that the well-dressed rich could cross the road and not dirty their clothes) and the pure-finders (who collected dogs’ dung). As well as these unfortunates, Mayhew lets us hear the voices of chimney-sweeps and refuse-collectors, street-acrobats and prostitutes.

Early investigative journalism

Mayhew’s accounts started life as a series of articles in the Morning Chronicle, for which newspaper Mayhew was given the role of ‘Special Correspondent to the Metropolis’ and instructed to provide descriptions of the ‘moral, intellectual, material and physical’ condition of the ‘industrial poor’. Mayhew’s distinctive blend of interviews and statistics proved extremely successful, and once he left The Chronicle he continued to publish in weekly pamphlets, and then in bound volumes, in the 1850s and 1860s.

Mayhew’s technique of giving centre stage to the poor themselves, and enabling them to tell their own stories, fascinated and overwhelmed the Victorian public. Suddenly a strange new world right under their noses was opened up to them; in this, Mayhew played an important part in the development of investigative journalism. Influenced as he was by 19th-century urban fiction, many of Mayhew’s interviewees seem like characters by Dickens. In the voice of one boy street-seller who speaks to Mayhew, we hear the echo of illiterate, baffled Little Jo, the crossing-sweeper from Bleak House: ‘Didn’t know what happened to people after death, only that they was buried … Had heer’d of another world; wouldn’t mind if he was there hisself, if he could do better, for things was often queer here’ (ch. 56).

Written by: Dr Mary L Shannon

Dr Mary L Shannon is a Lecturer in English Literature in the English & Creative Writing Department the University of Roehampton. She is interested in the connections between literature, journalism, drama, and visual culture throughout the 19th-century, and also in London’s cultural geography. Her first book, Dickens, Reynolds and Mayhew on Wellington Street: The Print Culture of a Victorian Street, won the 2016 Robert and Vineta Colby Scholarly Book Prize.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.