Anthropomorphism in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

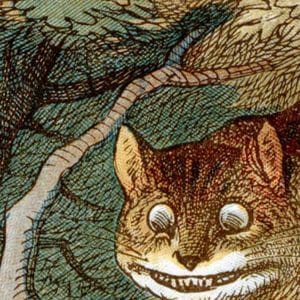

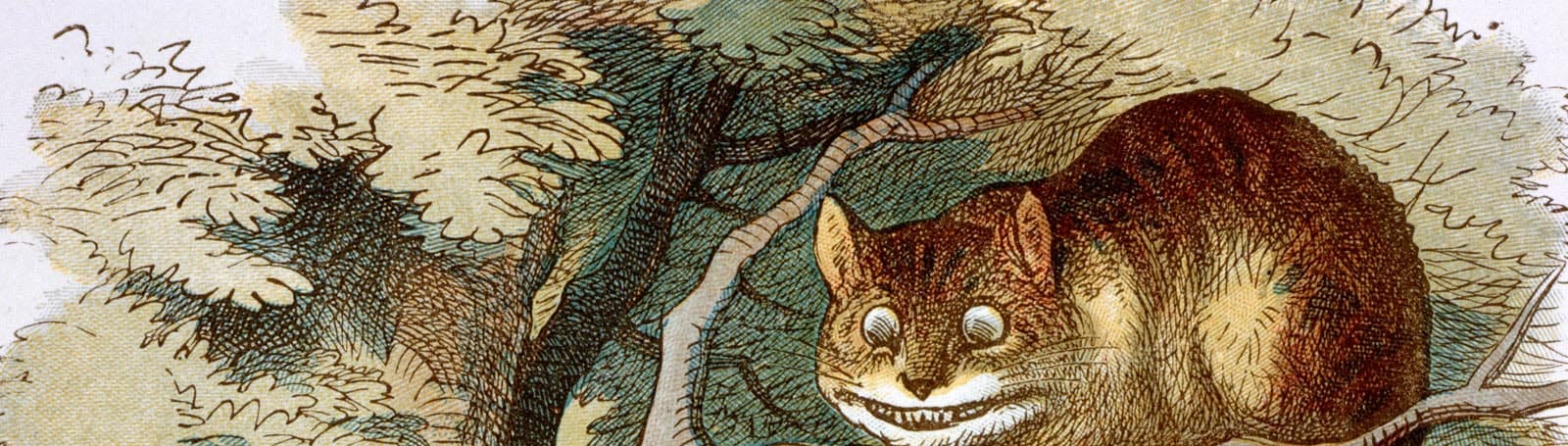

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is crammed with animals: a grinning cat, a talking rabbit, an enormous caterpillar and countless others. Dr Martin Dubois explores anthropomorphism and nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s novel, revealing the literary traditions that underpin it – and those it inspired.

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

(Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, ch. 6)

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice discovers a mad world that nevertheless manages to make a strange kind of sense. First published in 1865, her story is a classic of nonsense literature, a form of writing that became a phenomenon in the mid-19th century. We sometimes use the word ‘nonsense’ to indicate an absence of meaning. Nonsense literature, however, disrupts meaning rather than escaping it entirely. Some of its common techniques include the inversion of logic and language, the creation of curious juxtapositions, and experiments with size and scale. All these help to turn the familiar peculiarly out of place. In Carroll’s nonsense, animals and things behave almost like people, and talk almost like them too. Among many other oddities, Alice witnesses a rabbit check his pocket watch, has a conversation with a caterpillar smoking a hookah pipe, and hears a Mock Turtle (a creature who takes his name from a popular type of Victorian soup) sing a song.

This last aspect of Carroll’s nonsense – the inhabiting of the human by the non-human–is an ancient technique of writing for children. It was given fresh impetus in this period, not only by nonsense writers such as Carroll and his close contemporary Edward Lear, but also in children’s literature generally.

Nonsense

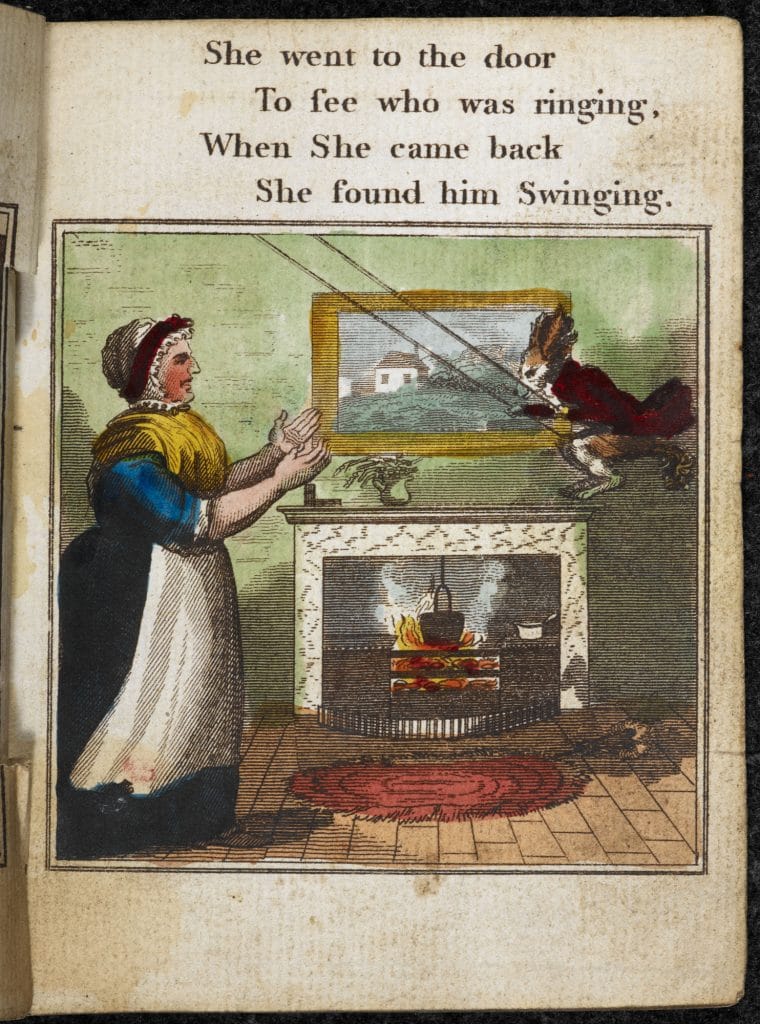

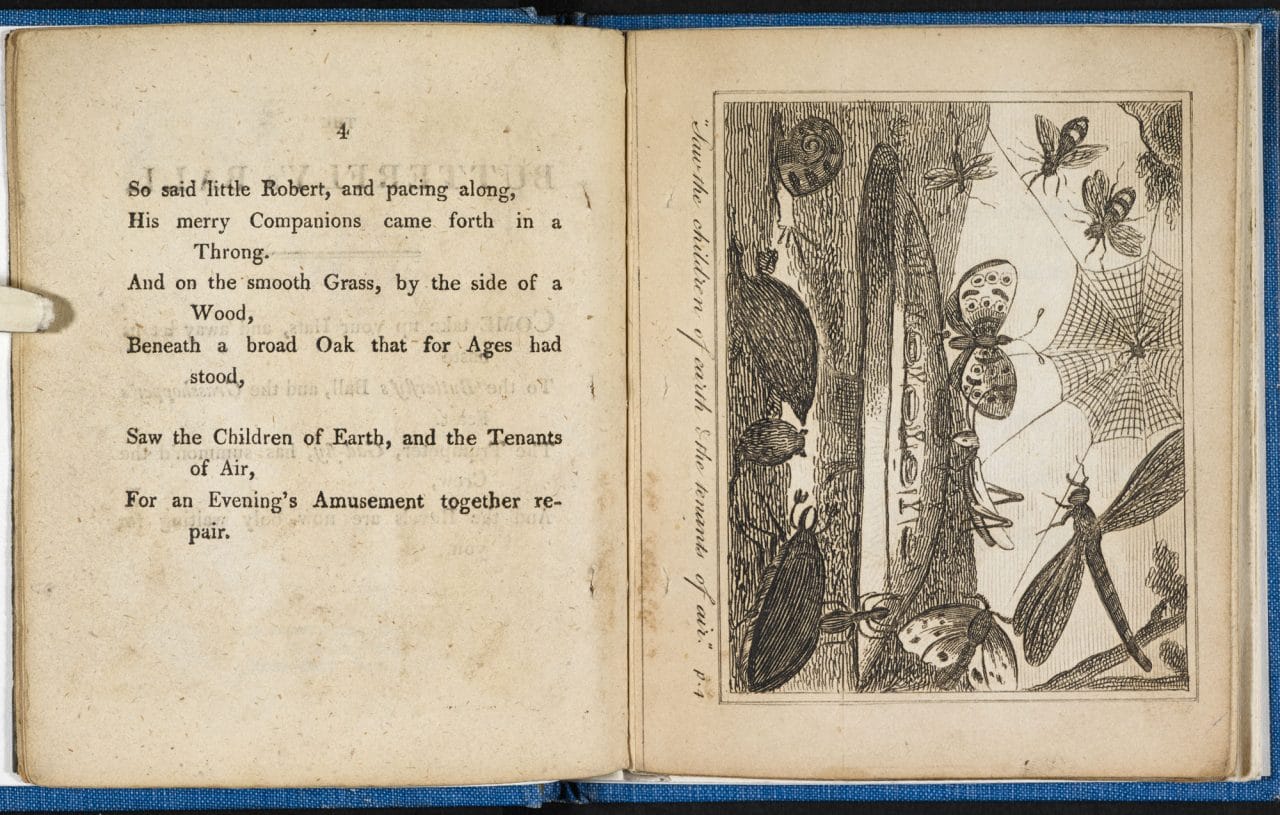

Literary nonsense did not originate in the 19th century, but it was during this period that the form came into its own. Carroll and Lear inherited a tradition of writing for children that had fun thinking of animals performing human actions. Part of the joke here is that the animals never entirely lose their individual animal characteristics upon becoming human. In William Roscoe’s fanciful poem of animal merriment, The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast (1806), entertainment is provided by a tightrope-walking grasshopper. This fact is strange enough, but even less probable is the promise of a snail to perform a slow and graceful ballroom dance (called a minuet) along the same rope, for which he is roundly mocked by his fellow revellers. A snail can turn up to the party, it seems, but to expect him to dance is to take the absurdity too far. In Sarah Martin’s The Comic Adventures of Old Mother Hubbard and Her Dog (1805), a dog variously smokes a pipe, plays the flute, rides a goat, and reads the news. Finally, his long-suffering owner, Dame Hubbard, returns home to find him dressed in his clothes, at which point matters make an unlikely return to something closer to normality:

The dame made a curtsey,

The dog made a bow;

The dame said, Your servant, The dog said, Bow-wow.

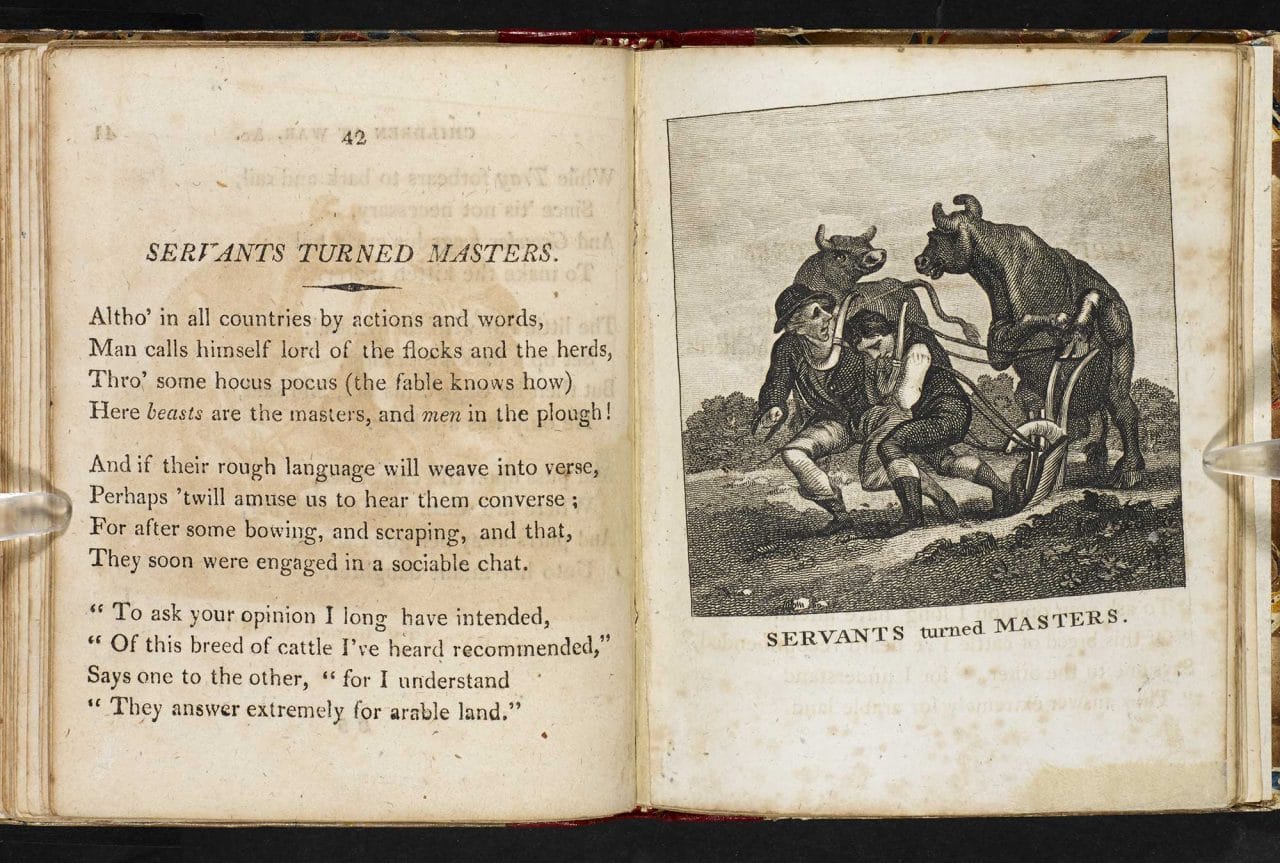

The many ‘World Turned Upside Down’ chapbooks (cheaply printed, pocket-sized books) in the 18th century delight in the same kind of absurd role-reversal, but with an additional eye to the violence done to animals by humans: the goose roasting a cook and the fish hooking a man pictured in these chapbooks exact a form of animal revenge. Fish also turn into fishers in Ann and Jane Taylor’s children’s version of the ‘World Turned Upside Down’, Signor Topsy-Turvy’s Wonderful Magic Lantern (1810). Usual hierarchies are subverted in their book, so that stags become huntsmen and birds become fowlers. This sometimes creates a moralising effect, as in episodes such as ‘Children at War, and ‘Cats and Dogs at Peace’, which attempt to shame children into good behaviour, and sometimes not, as in ‘The Ass Turned Elephant’, in which an ass borrows an elephant’s trunk in an effort to be taken seriously, with no obvious moral significance.

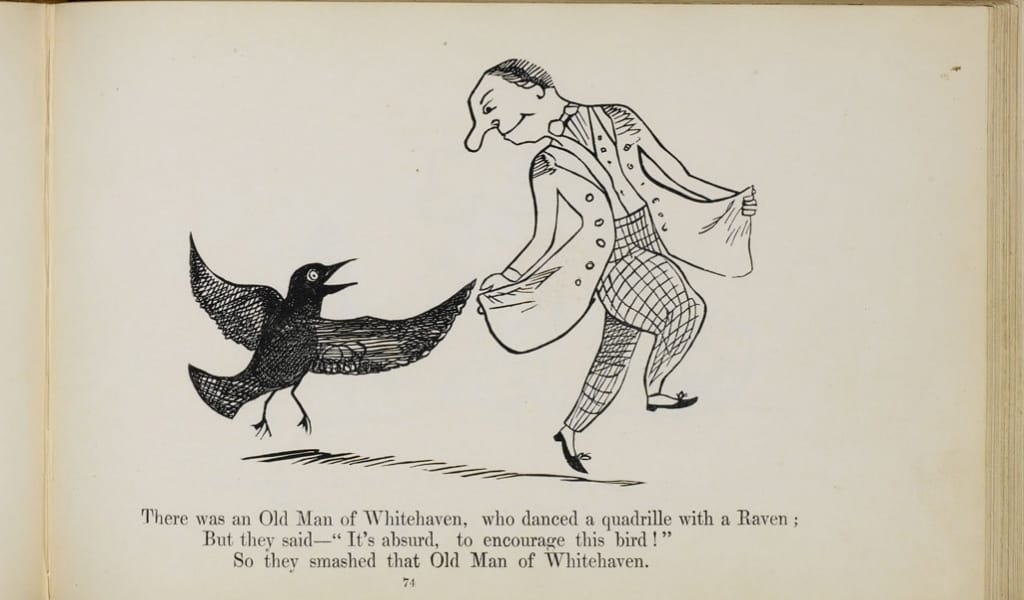

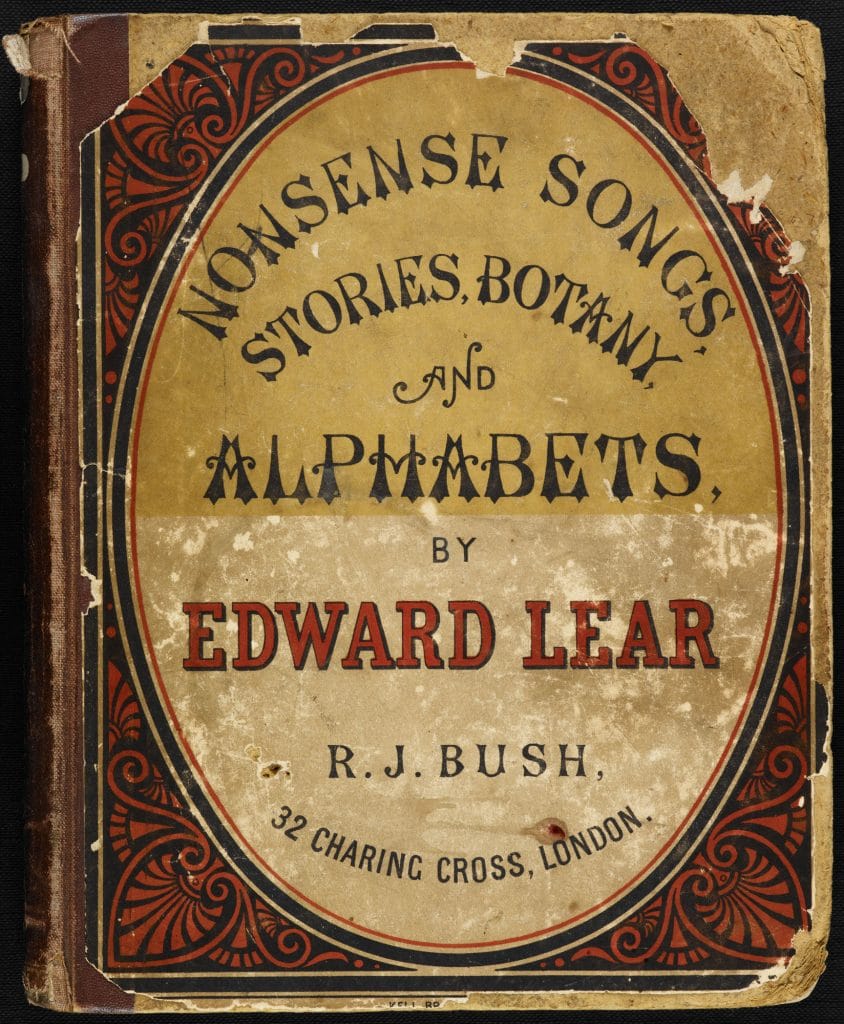

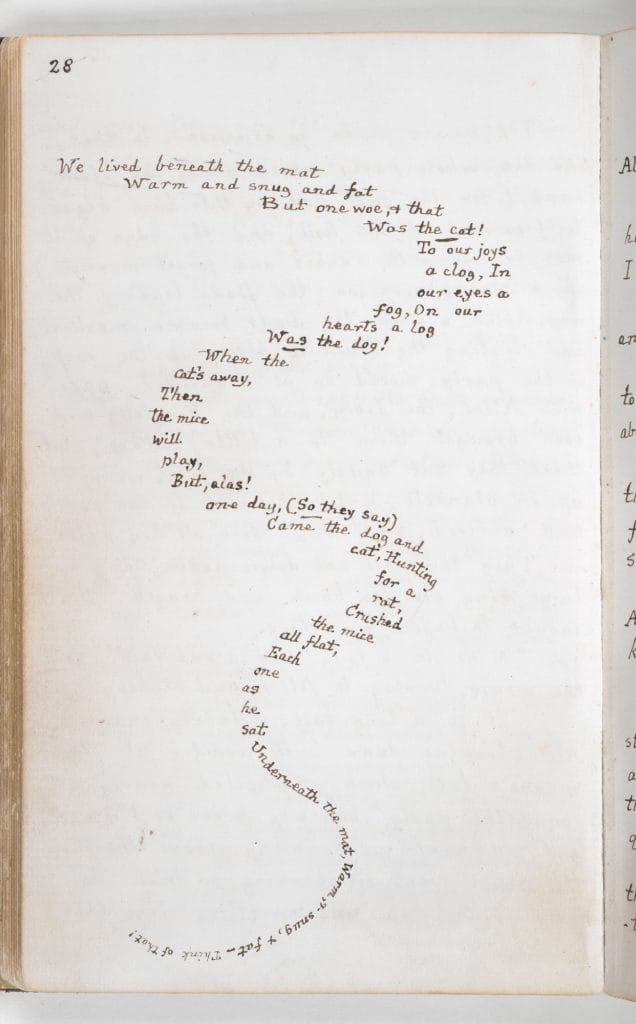

Lear and Carroll’s nonsense plays a more incongruous game with logic and expectation. It puzzles and disturbs as well as amuses. Lear’s first nonsense publication was A Book of Nonsense (1846), in which limericks were accompanied by his own illustrations. His cast of eccentrics often meet with baffling violence, as in the Old Man of Whitehaven limerick. Other Lear nonsense mixes laughter and sadness, as in his Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets (1871), a volume which includes ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’ and ‘The Jumblies’. ‘The Daddy Long-legs and the Fly’ involves just such mixed emotion. The fate of its pair of misfits – the daddy long-legs too long to ‘sing the smallest song’, the fly too short to go to court – is both ridiculous and tragic. Relief of a kind is provided by their departure for ‘the great Groomboolian plain’, where they ‘play for evermore / At battlecock and shuttledore’, but the escape to the idyll, we cannot forget, is also a flight from trouble.

Carroll’s nonsense is more analytical, delighting in puns, paradoxes, and word games. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland began life as a story Carroll (whose real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) told to his young friend, the 10-year-old Alice Liddell. He subsequently wrote out the tale for her by hand, and called it Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. The British Library owns the original manuscript. The later success of the published version was immediate, and Carroll followed it with another Alice book, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871). Here and elsewhere, Carroll’s word games highlight the social conventions of language use. So-called ‘portmanteau’ words in the poem ‘Jabberwocky’ pack up two meanings into one word: ‘slithy’ means both ‘lithe’ and ‘slimy’; ‘frumious’ combines ‘furious’ and ‘fuming’; and ‘chortle’ (a word in common use today, but invented by Carroll) is a mixture of ‘chuckle’ and ‘snort’ (Alice Through the Looking-Glass, ch. 1). To understand what words mean in this scenario, you need to know the rules that govern their usage. Carroll’s other nonsense works include a long poem, The Hunting of the Snark (1876), in which the rules directing meaning are if anything more obscure. Its puzzlingly indeterminate final line – ‘For the Snark was a Boojum, you see’ – was said by its author to have provided the inspiration for the poem as a whole.

Anthropomorphism

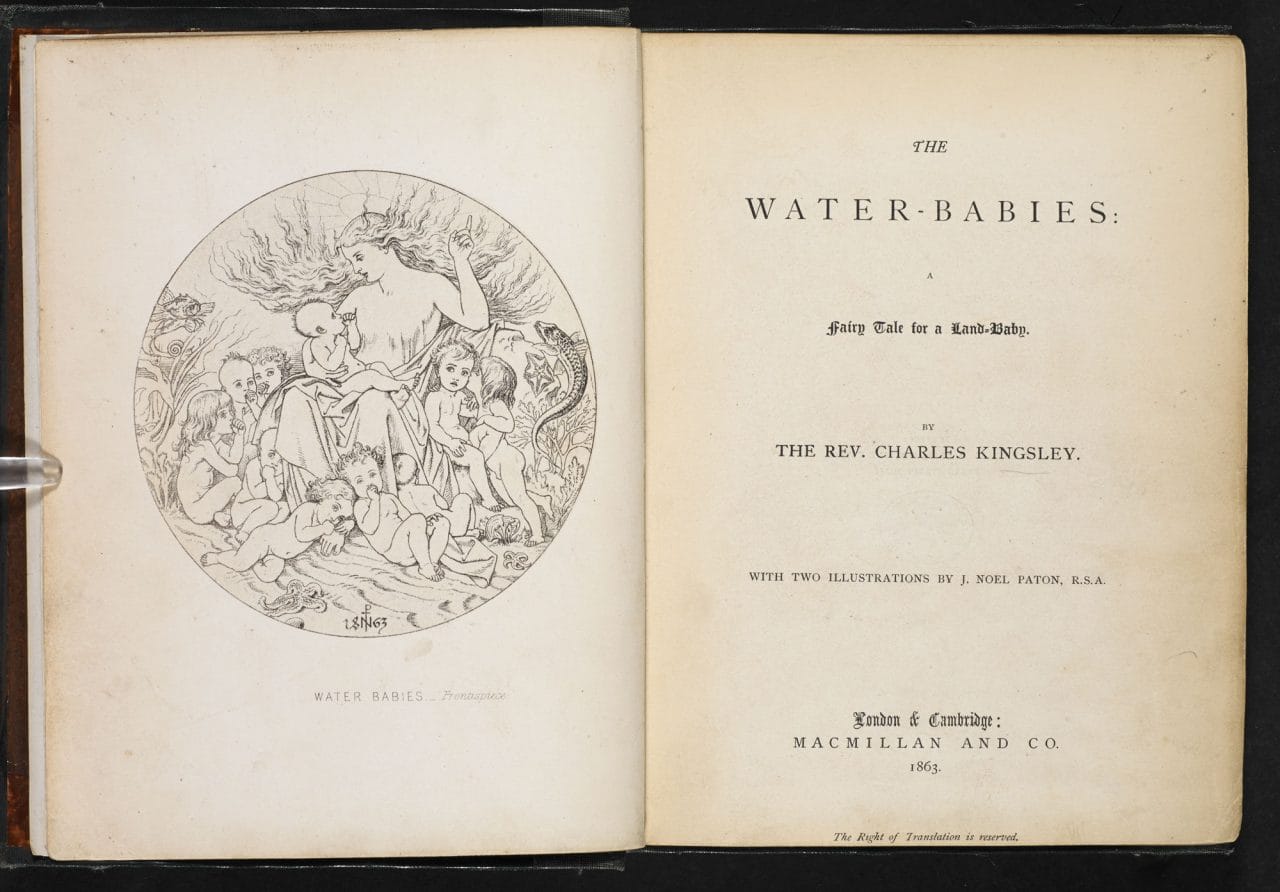

Carroll and Lear’s writing has been thought to herald a break with moralizing in children’s literature, yet it can also be seen to approve certain codes and values of behaviour. Alice’s adventures are absurd but not meaningless, and her return to the real world at the end of the book contains a lesson about the necessity of growing up. Other anthropomorphic children’s texts of the period also have a complicated relationship to didacticism. The chimney-sweep hero of Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies (1863) falls into a river and is transformed into an amphibious water-baby, beginning an adventure among water animals that is also an education in life. Kingsley’s bizarre and digressive book represents, among other things, an idiosyncratic response to the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species a few years earlier.

A different use of anthropomorphism is made in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Books (1894-95), a blend of animal fable and adventure story that has often been read in the context of British imperial culture. The boy-hero Mowgli has to learn the Law of the Jungle, an education in a social code that is sometimes said to parallel the ‘civilizing mission’ of British imperialism. The turn to animal fantasy seen in Kingsley and Kipling was also a distinctive feature of early 20th-century children’s literature, most notably in Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit books (1902-1912) and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Martin Dubois

Dr Martin Dubois is a lecturer in Victorian literature at Newcastle University. His current research falls into a few main areas: Victorian poetry, especially Hopkins; Victorian literature and religion; nonsense. He co-writes the annual review essay on Victorian poetry for The Year’s Work in English Studies.