Fantasy and fairytale in children’s literature

Professor M O Grenby explores the relationship between fantasy and morality in 18th and 19th-century children’s literature.

It is not as easy as one might think to define fantasy literature, or even the fairy tale. Must a fairy story contain actual fairies for instance? Or is the presence of an ogre, a talking cat, or of larger-than-life characters like Bluebeard enough? Must a fantasy story take place solely in a made-up land, or is it ok if the characters casually slip between our world and the other worlds? And must the fantasy world be full of wonders, impossible in our world, or do alternative universes which are actually rather banal and similar to our own count? What about journeys to strange worlds which turn out to be the past, or the future, of our own? What about worlds that turn out to be merely a character’s dream or hallucination? What about ghost stories, or superhero stories, or utopias, or satires, or stories in which animals are given thoughts and intelligible voices? In short, fantasy literature, and the fairy tale, are amorphous and ambiguous genres, whose boundaries are actually very difficult to set. What is certain, however, is that both fantasy and fairy tale literature have proved hugely popular with children. Indeed for many young readers, and critics, these genres are the core of children’s literature. But the place of this kind of make-believe literature in children’s culture has not always been secure, and it has a complex history.

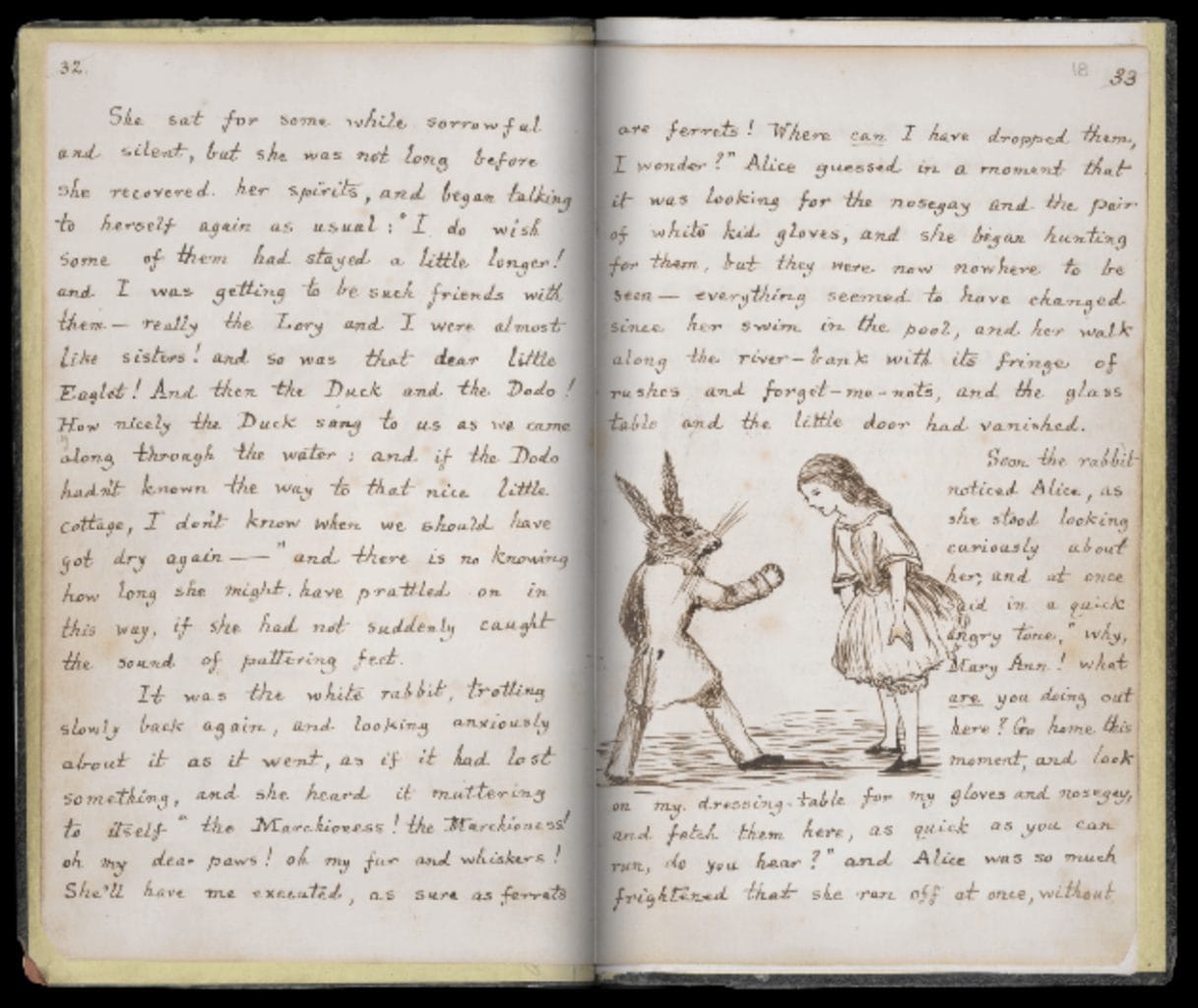

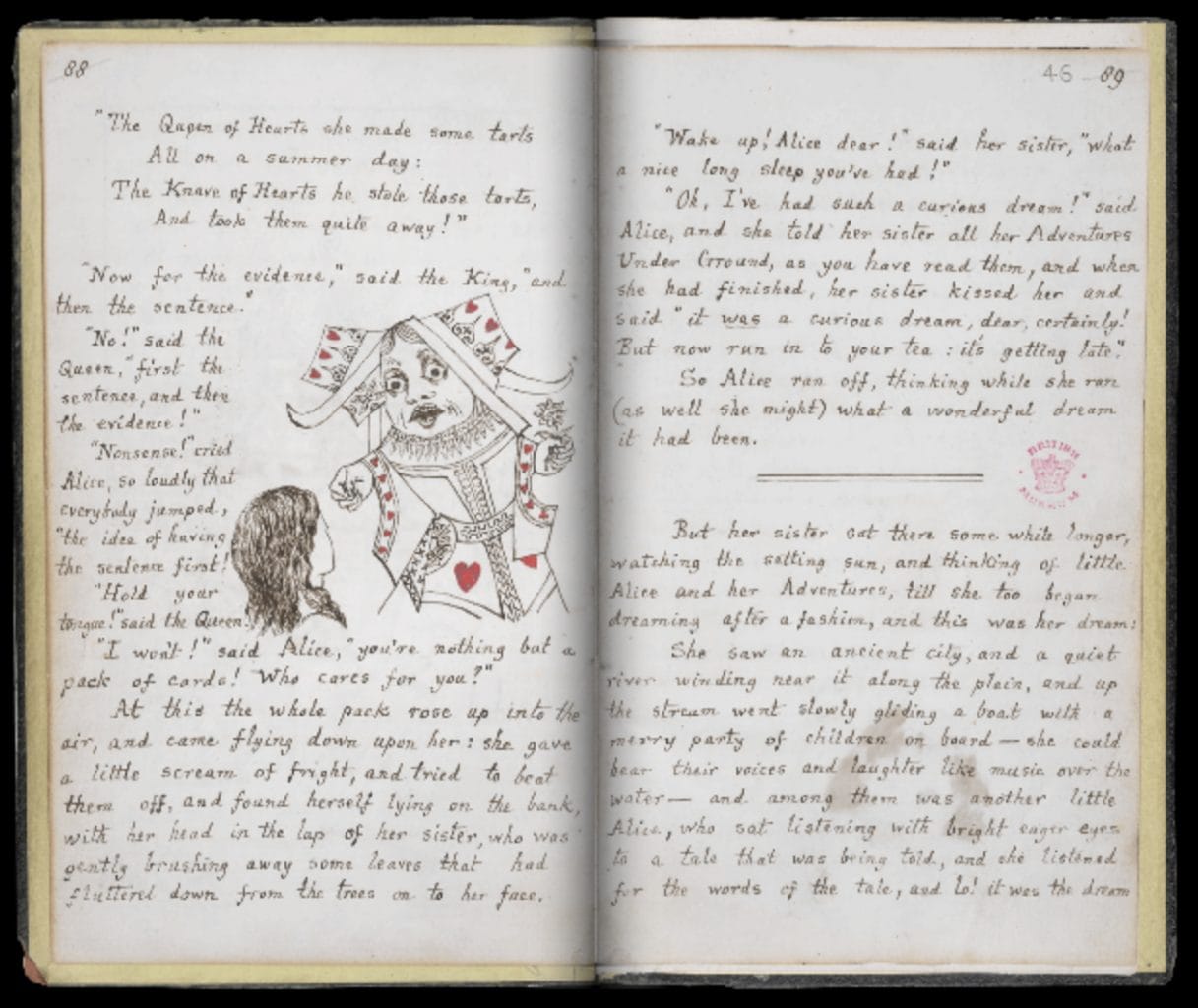

Historians of children’s books have often seen two forces – realism and didacticism on the one hand, and fantasy and fun on the other – as constantly in competition. Didactic literature, they argue, dominated in the 18th century, but in the Romantic period, around the start of the 19th century, the fantastic (they say) finally began to win the battle. The Brothers Grimm’s fairytales, first published in German in 1812, were translated into English in 1823. Hans Christian Andersen’s stories began to appear in the 1830s (first translated into English in 1846). And Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published in 1865. All these books can be seen as marking the beginning of a ‘Golden Age’, with fantasies of various kinds, like E. Nesbit’s Five Children and It (1902), Beatrix Potter’s Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904), Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and, in America, L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), setting the stage for the great fantasy writers of the 20th century, notably C. S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Philippa Pearce, Lucy Boston, Alan Garner and Philip Pullman.

Stories of spirits, ghosts and goblins

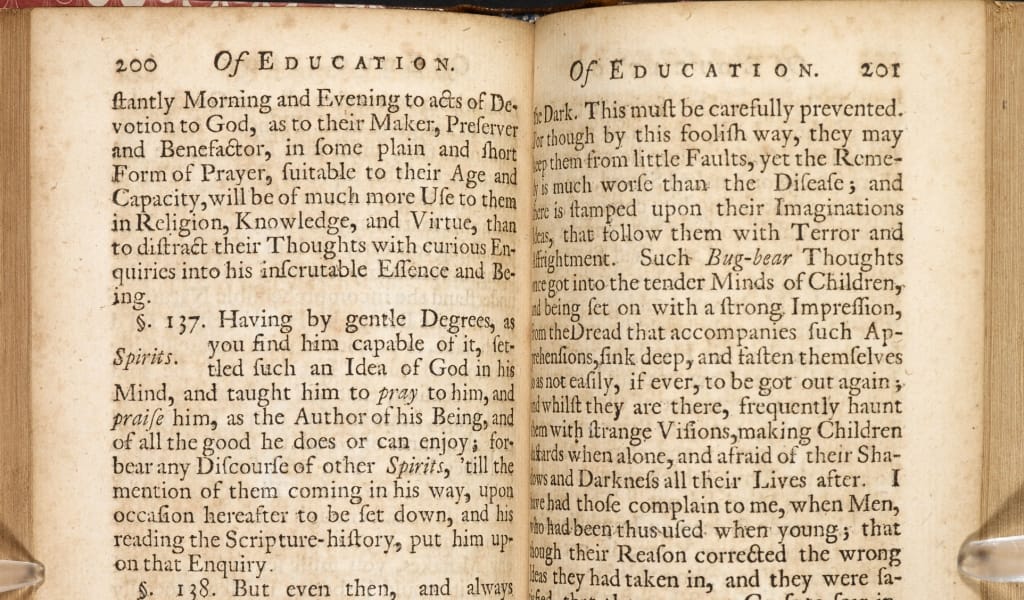

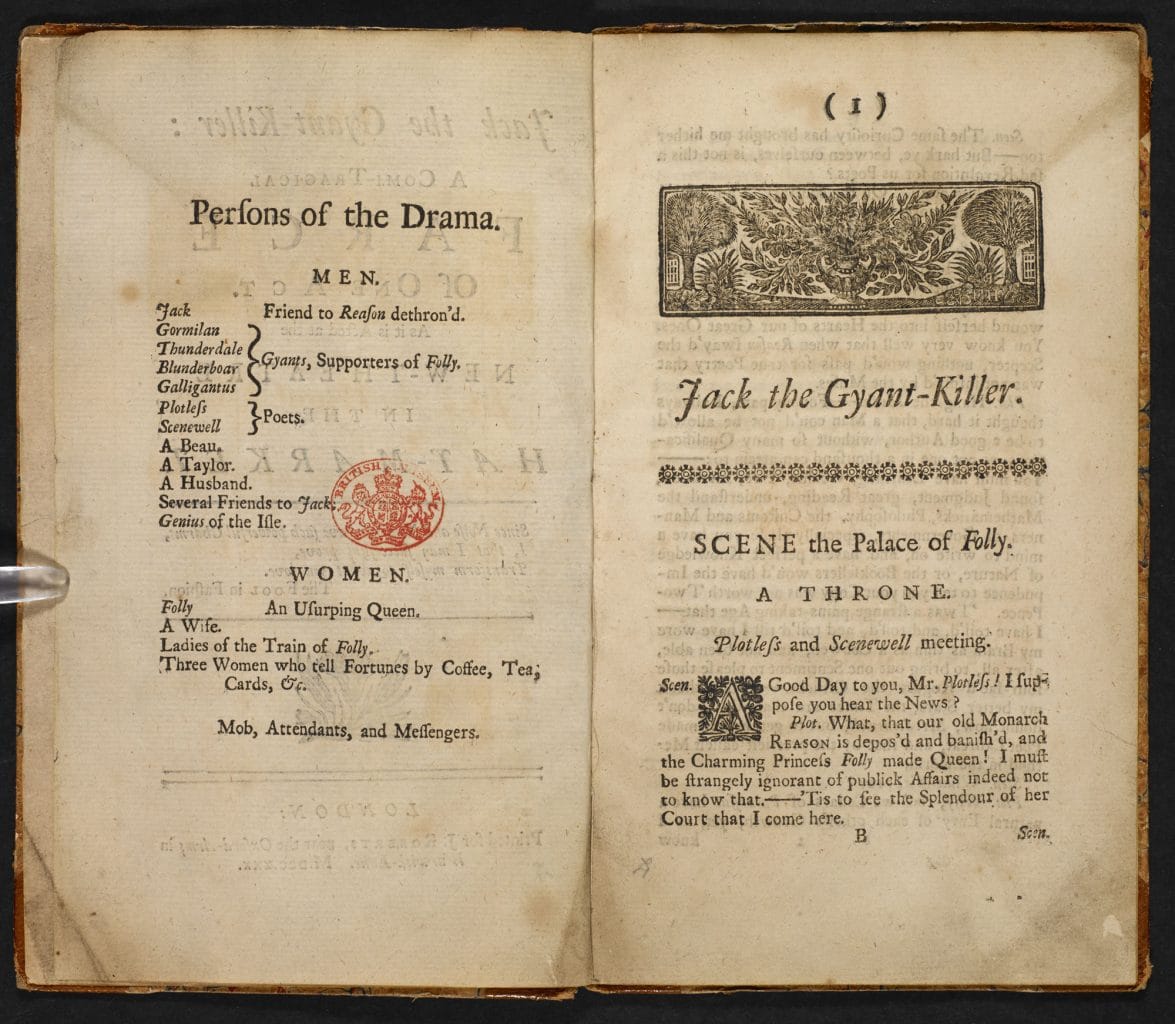

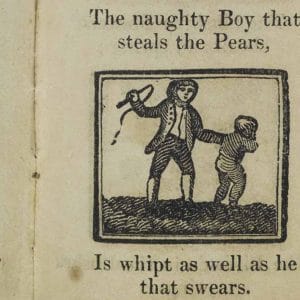

There are, however, several problems with an account that pitches fantasy and fairytale into a simplistic battle with realism and didacticism. First of all, there’s the question of whether didactic and realist children’s literature was really so dominant in the 18th century. Certainly it was the case that many 18th-century educationalists cautioned against introducing children to the supernatural. The philosopher John Locke, writing in Some Thoughts Concerning Education in 1693, influentially warned parents and teachers not to tell stories of ‘spirits and goblins’ in case they frightened the children in their care. But we should note that Locke had multiple agendas. He was concerned that supernatural tales were the province of servants and the poor, and one of his main aims was to remove the children of the middle and upper classes from the influence of their social inferiors. We should also remember that for most children in 18th-century Britain, stories of ghosts and goblins, and popular tales like Fortunatus (with his bottomless purse and magic hat) and Jack the Giant-Killer, would have been standard fare, whether told orally or published in cheap and flimsy chapbooks.

Moral fairytales

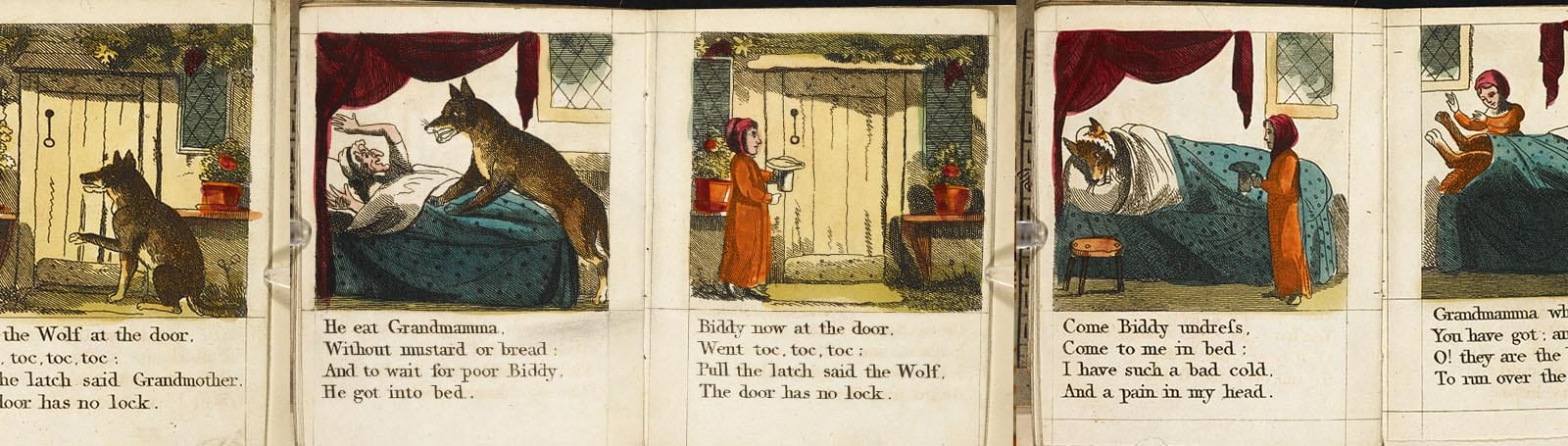

In any case, the more respectable children’s literature that began to emerge for the first time in the 18th century was far from devoid of fantastical elements. One highly regarded favourite in middle- and upper-class families were the fairytales of Charles Perrault, first published in France in the 1690s and in English in 1729. They contained morals alongside the supernatural elements. ‘The Little Red Riding Hood’, for instance, ended with a warning for ‘growing ladies fair’ against wolves ‘With luring tongues, and language wondrous sweet’ who ‘Follow young ladies as they walk the street’. And although fairytales continued to be criticised by Lockean educationalists, new editions were printed especially for children throughout the century. Similarly, following their first appearance in English at the start of the 18th century, the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments were quickly taken up by a juvenile audience. By the end of the century they were being published in editions designed especially for children, with added didacticism. The compiler of The Oriental Moralist or the Beauties of the Arabian Nights Entertainment (1791), Richard Johnson, admitted that he had ‘added many moral reflections, wherever the story would admit of them’ and ‘considerably altered the tales … to fortify the youthful heart against the impressions of vice’.

But in fact the line between fantasy and didacticism had always been very blurred. Even the mid 18th-century pioneers of the ‘new’ children’s literature would often include fantastical elements in their supposedly rationalist and instructional books. John Newbery’s Lilliputian Magazine (1751-52), for instance, included accounts of several voyages in which young boys and girls find themselves in strange lands populated by bizarre creatures or full of fairytale possibilities. One story takes us to ‘Angelica’, for instance, where there lives a race of tiny people with three eyes, one on the tip of their right-hand middle finger, which can be thrust down someone’s throat to determine moral worth. Another story takes us to ‘Petula’, where a poor London orphan named Polly, eventually becomes queen because of her great virtue, and lives in ‘a palace of jasper, the front of which was overlaid with pure gold, the floor paved with pearls and emeralds, and the ceilings adorned with the most curious paintings of sacred history’.

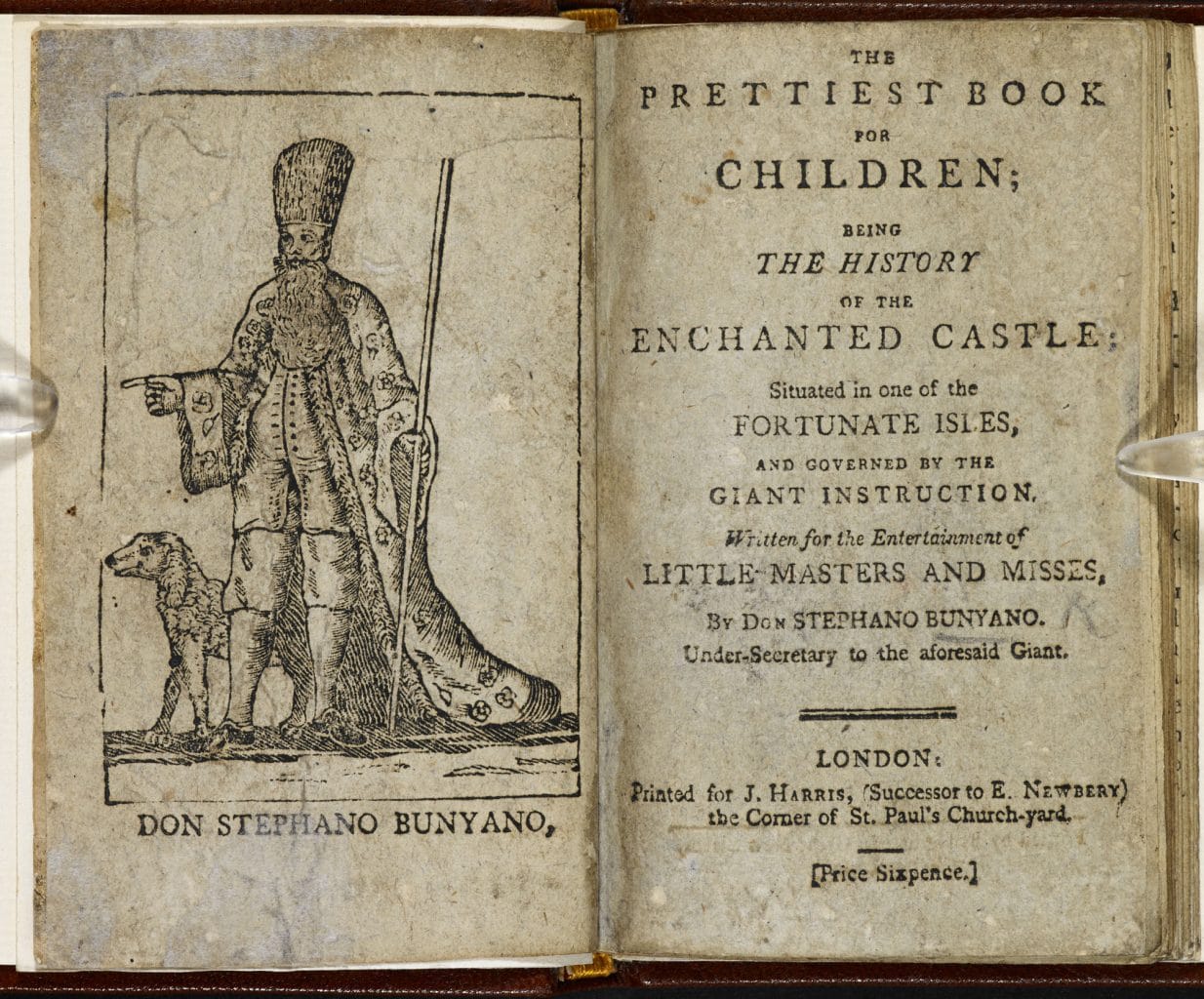

These are moral tales certainly, but they are not so very dissimilar from C S Lewis’s Narnia stories or the many other ‘alternative world’ fantasies of the 20th century in which undistinguished children find themselves transported to weird and wonderful lands where they suddenly wield great power. Another example of an 18th-century ‘moral fantasy’ is The Prettiest Book for Children; Being the History of an Enchanted Castle; Situated in one of the Fortunate Isles (1770). Here, the ‘enchanted castle’ belongs to a giant called ‘Instruction’, who employs new methods to teach children lucky enough to find themselves there. Again, this isn’t so very different from more modern fantasy literature. Alice’s Wonderland and the Never Never Land in Peter Pan are really spatial representations of childhood itself, from which adults are debarred and where children can behave entirely as they ‘ought’. The Never Never Land, with its pirates, ‘Indians’, fairies and mermaids and their eternal games and stories, represents Barrie’s idea of what childhood would look like if it could be plotted on a map. Similarly, the ‘Fortunate Isles’ in The Prettiest Book for Children is an adult writer’s fantasy of what childhood should be: a zone of cheerful and effective education.

Into the 19th century

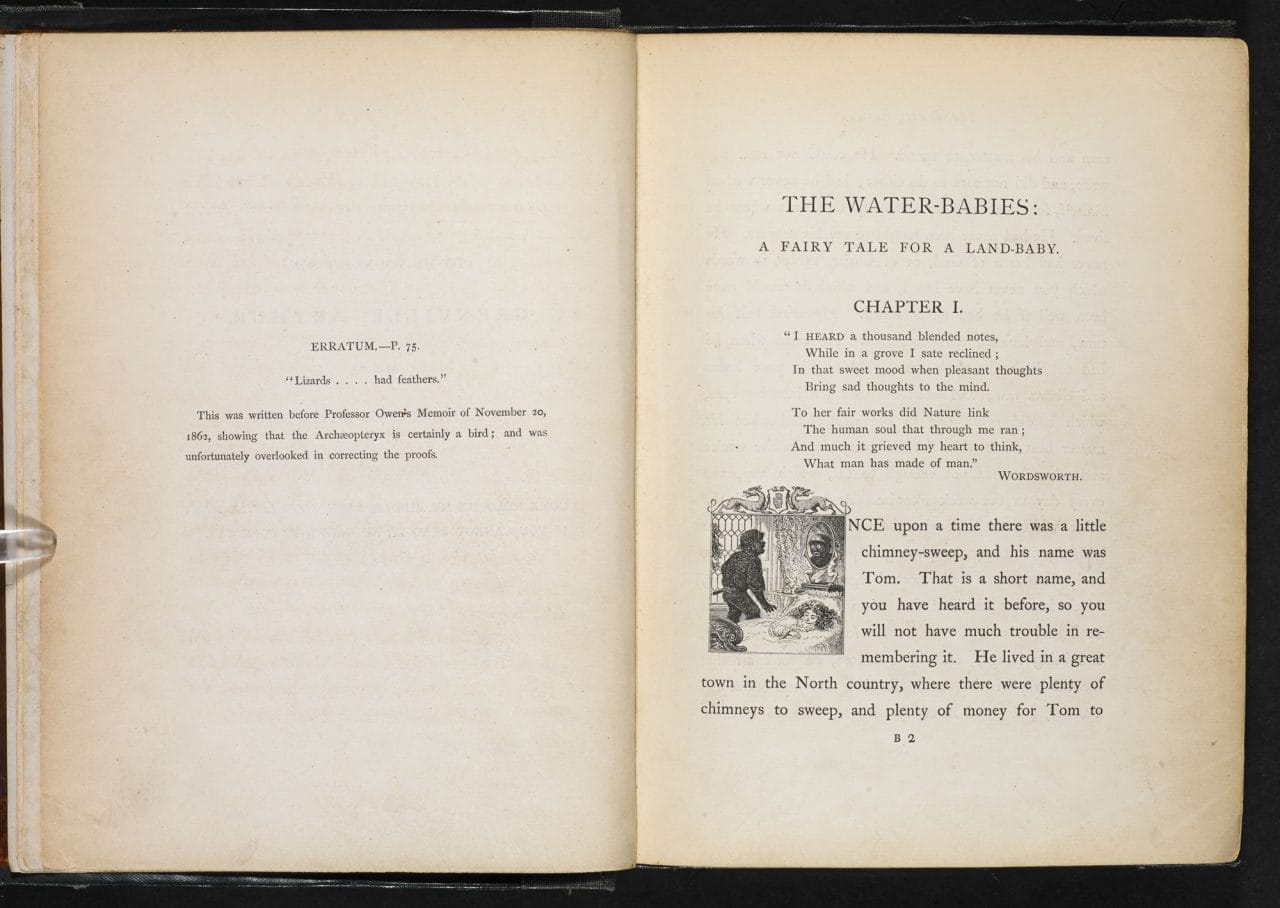

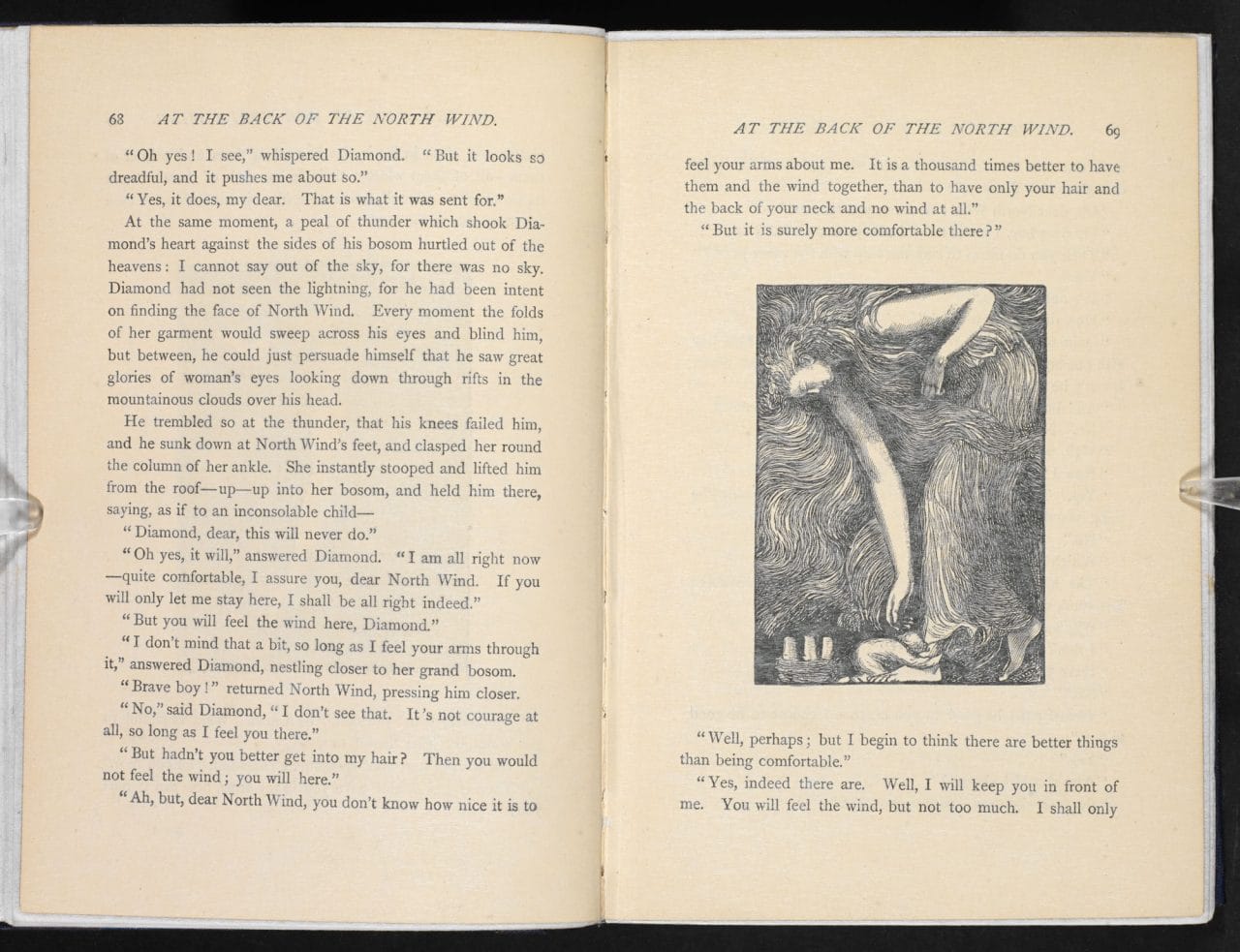

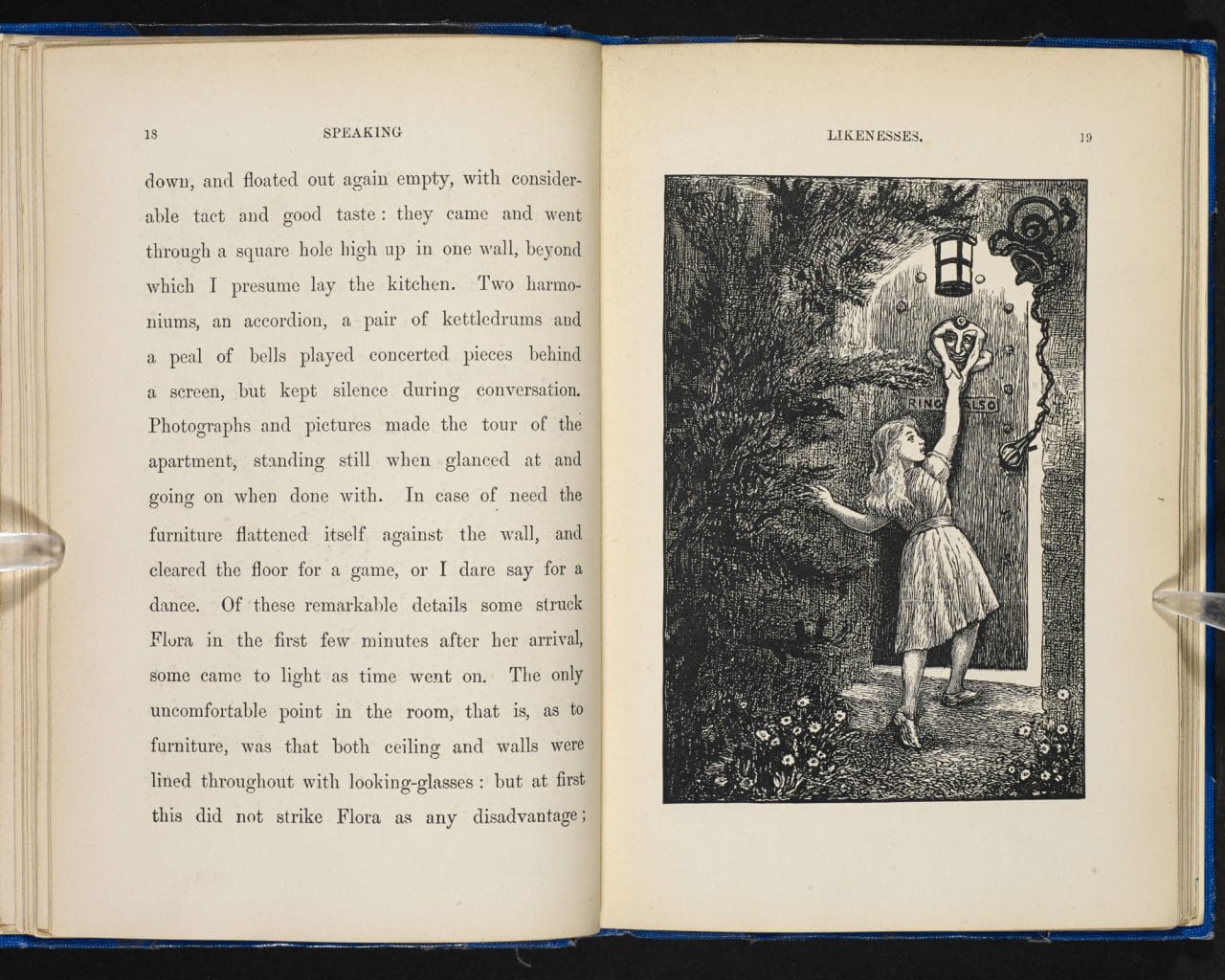

In the 18th century then, fantasy and didacticism could evidently happily coexist in the same books. But the same was also true in the 19th. A series actually called ‘Moral Fairy Tales’ appeared in the 1820s, including such titles as Miss Selwyn’s Mary and Jane; or, Who Would Not Be Industrious? Not dissimilar was Christina Rossetti’s Speaking Likenesses (1874), an imitation of Carroll’s Alice in which the heroine finds herself transported to a world where children’s exteriors exhibit their disagreeable moral characters. In 1853, George Cruikshank, who had illustrated the Brothers Grimm’s tales, began to rewrite fairy stories so that they included obvious anti-alcohol lessons (infuriating Charles Dickens, who, in keeping with the Romantics’ reverence for what they thought a sacred trove of ancient stories, attacked such ‘meddling’ in his 1853 essays ‘Frauds on the Fairies’). And it is difficult to think of a more preachy book than Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (1863), one of the most celebrated of all children’s fantasies but also including substantial amounts of moralising and a large dose of social realism in its attack on child chimney sweeps. George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871) is another hybrid: part fairytale, part social realism, and part religious allegory.

Even Alice, if looked at in a certain light, can seem rather didactic. Carroll mocks the cautionary tale: the ‘nice little histories’ Alice has read, ‘about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts and other unpleasant things, all because they WOULD not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them: such as, that a red-hot poker will burn you if your hold it too long; and that if you cut your finger VERY deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds’. But Alice does learn as she goes through Wonderland and then the Looking-Glass world. After falling down the rabbit hole (a sort of birth) and wrestling with the Caterpillar’s interrogation about who she actually is, she gradually grows up, encountering small, cuddly creatures first, then scarier figures like the Duchess and the Queen, dealing with increasingly adult concerns (anger, death, judgment), and understanding how to comply with strange rituals like the croquet match. All the time she is gaining a stronger sense of herself until, at the end of the second book, she finally comes into her own by becoming a queen on the chessboard. Much fantasy literature seeks to teach similar lessons in empathy and what the Germans call Bildung (‘formation’, ‘self-education’). In F. Anstey’s Vice Versa (1882), for example, a boy and his father find they have swapped bodies and must learn to live in each other’s places. And in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Selfish Giant’ (from The Happy Prince and Other Tales, 1888), characteristically for late Victorian writing, it is the adults (represented by the giant) who learn from the children as much as the other way round.

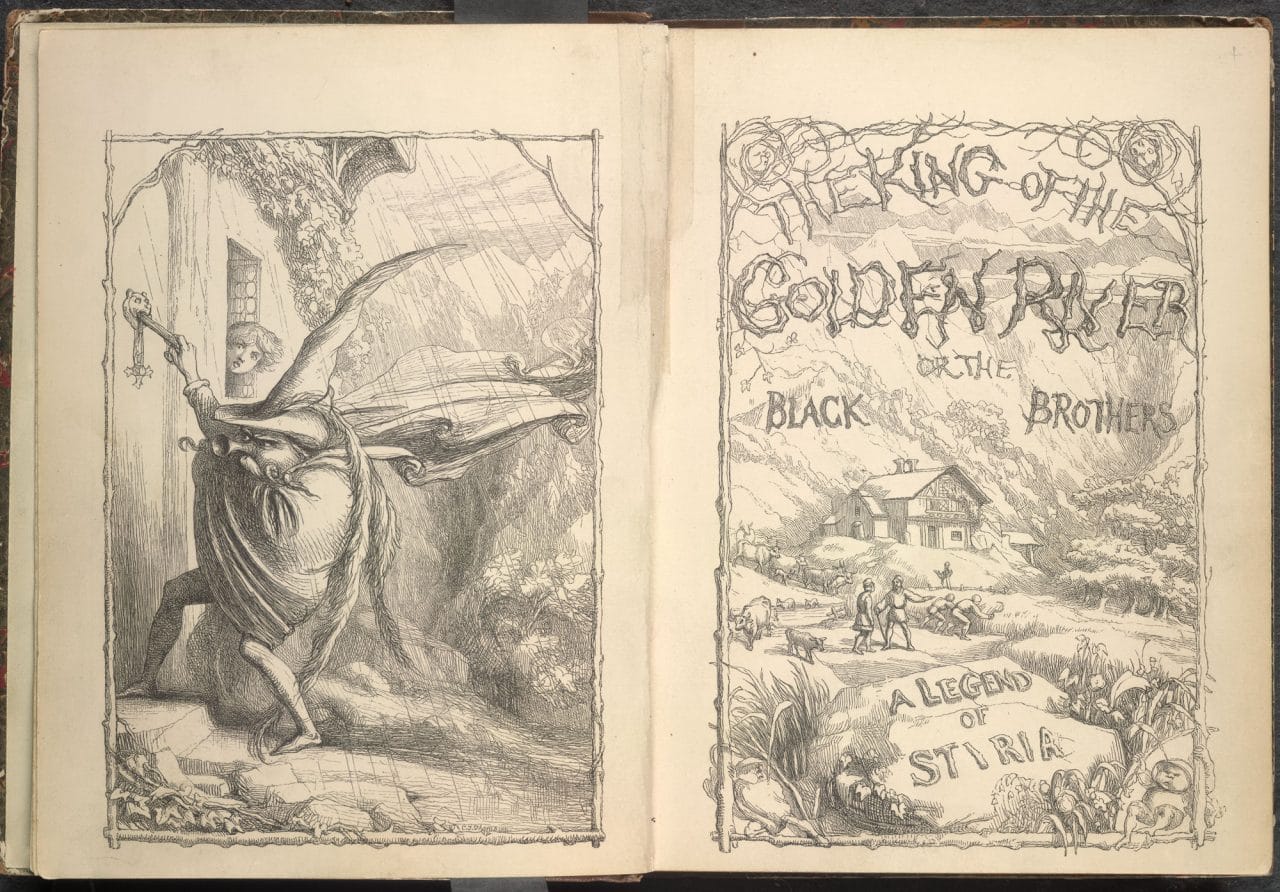

Why fantasy literature became so popular in the 19th century is not exactly clear, but its success was surely linked to rapid social, economic and intellectual change. Social reformers like John Ruskin and William Morris may have seen in the fairytale tradition, with its medievalism and its privileging of individualism, honour and the ‘old ways’, an antidote to the industrial and urban society whose advance they regretted. (Both Ruskin and Morris wrote successful fantasy novels: respectively The King of the Golden River, 1851; and The Well at the World’s End, 1894). Dickens, in his ‘Frauds on the Fairies’, wrote that ‘In an utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that Fairy tales should be respected’.[1] Kingsley’s Water-Babies was, in part, a response to Charles Darwin’s On the Origins of Species, published only four years earlier, and Nesbit’s innovative time-shift fantasies, such as The Story of the Amulet (1906) were clearly influenced by the same developing ideas in physics that inspired H G Wells’s The Time Machine (1895). Whatever led to the rise of fantasy literature, two things are clear. Firstly, by the end of the 19th century children were having a vast range of fairytales and fantasy literature written for them. And secondly, this literature was not quite so different as we might at first think from the realistic and didactic texts that fantasy and fairytales have sometimes been seen as displacing.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: M O Grenby

M O Grenby is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies in the School of English at Newcastle University. He works on 18th-century literature and in particular on the early history of children’s books. His published works include The Anti-Jacobin Novel, The Edinburgh Critical Guide to Children’s Literature and The Child Reader 1700-1840, and he co-edited Popular Children’s Literature in Britain and The Cambridge Companion to Children’s Literature.