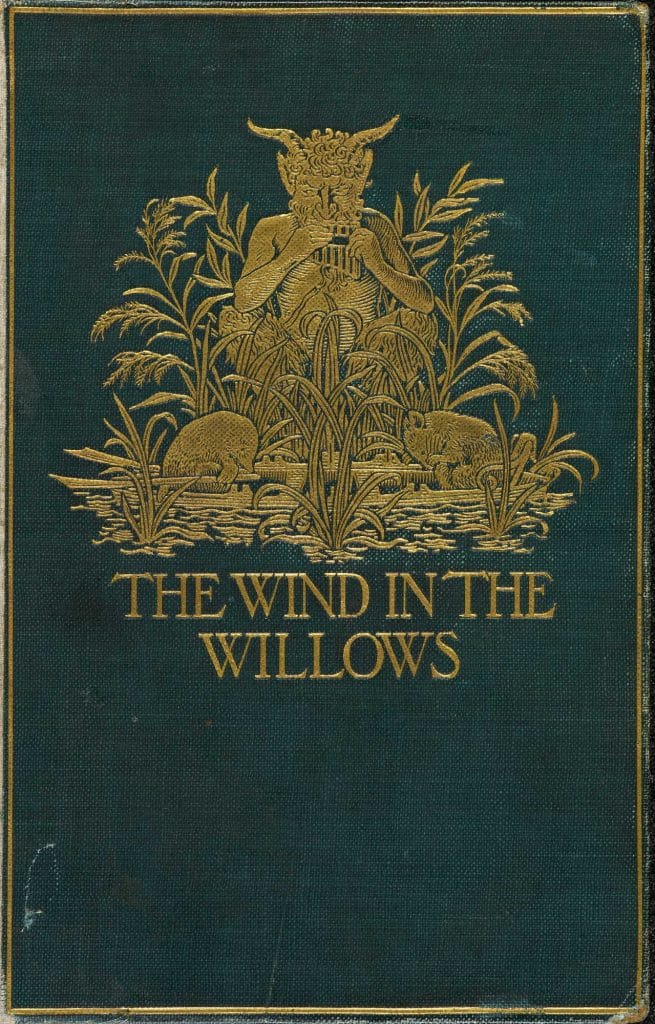

Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows

出版日期: 1908 类型: Children's Literature

Few British children’s books are as adored as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. In the century or so since it was published, this evergreen tale of a mole, a toad, a water vole and badger and their journeys through the English countryside has been loved by readers of all ages, and inspired numerous movie, TV and cartoon representations. But despite its evocation of an apparently timeless world, the novel is much more complex and grown-up than is often made out, a sharp-eyed social satire that has much to offer adults too.

The Wind in the Willows

The Wind in the Willows probably began as the bedtime stories Grahame told his young son Alastair. The idea of a saga focussing on the riverbank adventures of Mole, Ratty, Badger and Toad seems to have occurred to Grahame sometime around 1904, and by 1907 the characters (and much of the Toad-related material) crop up in letters sent to Alastair during the summer holidays.

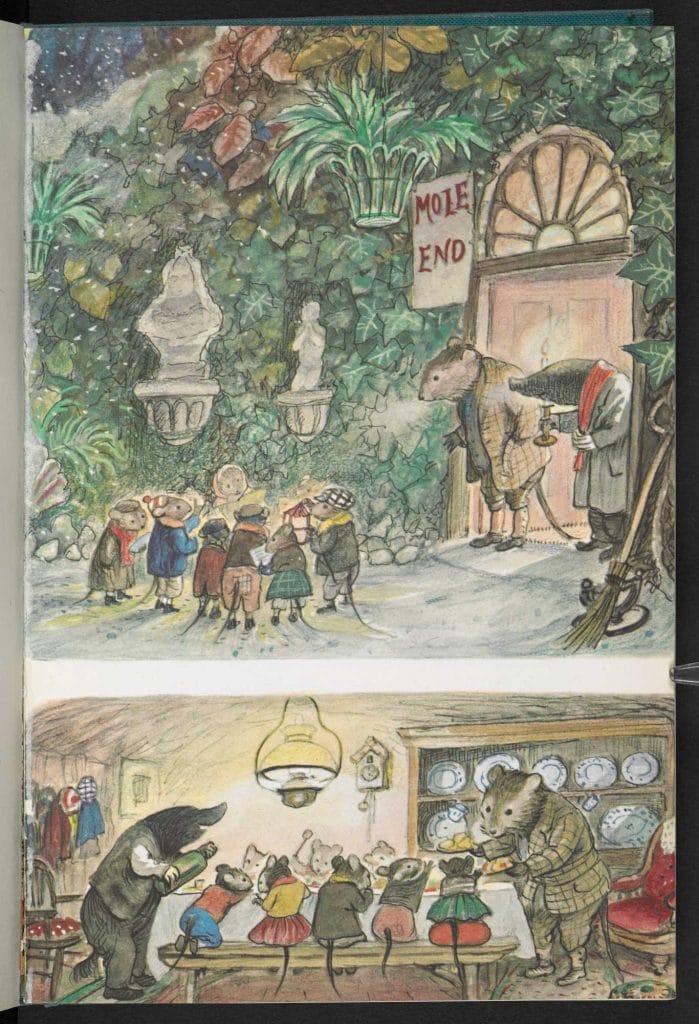

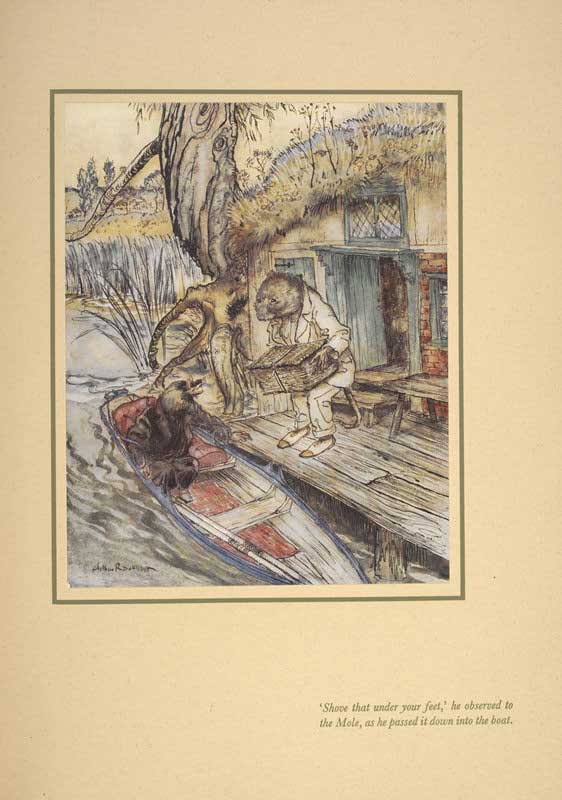

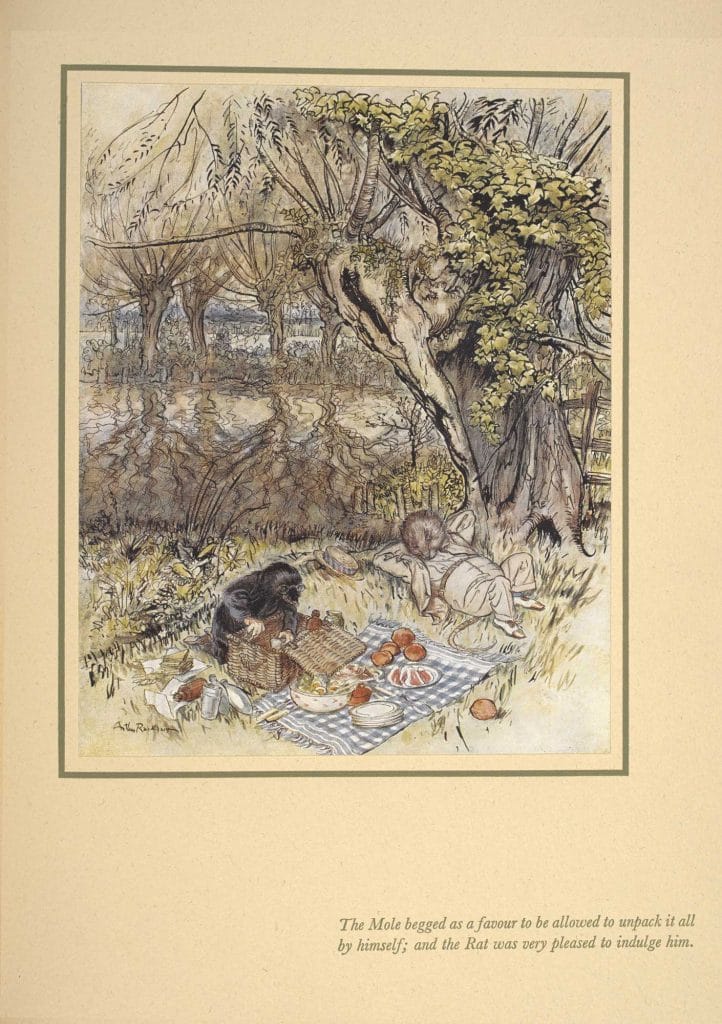

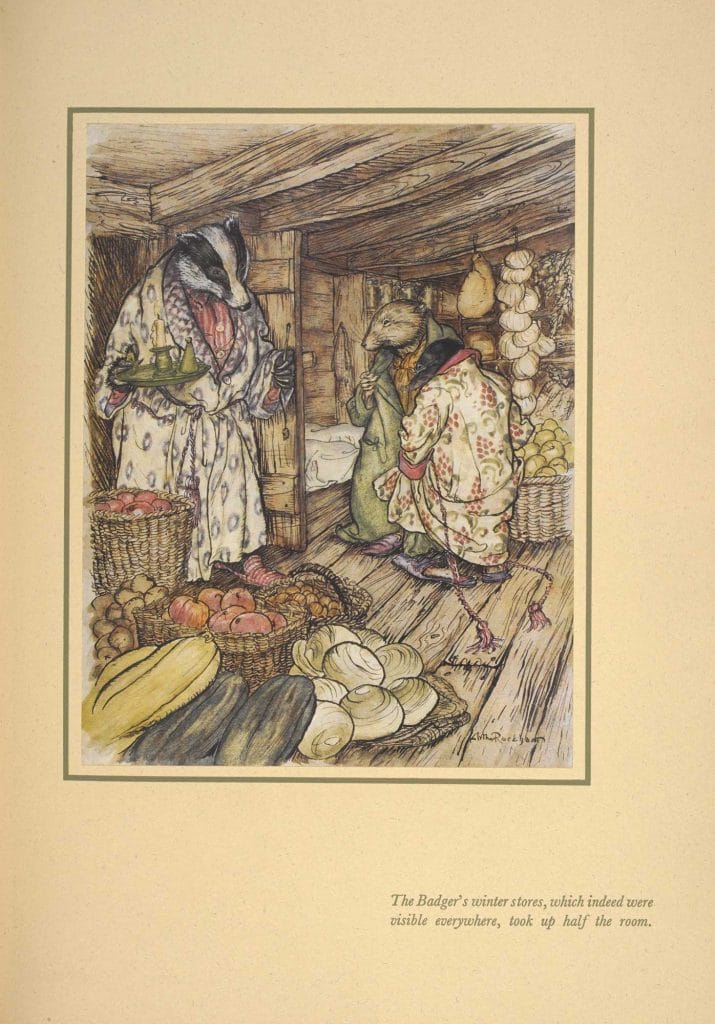

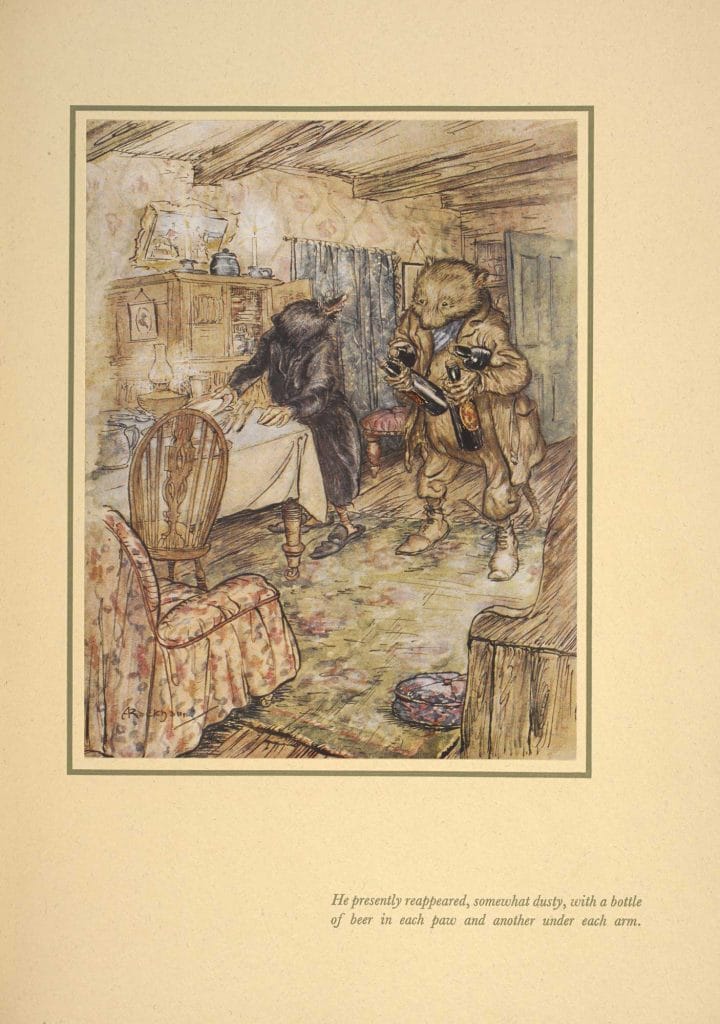

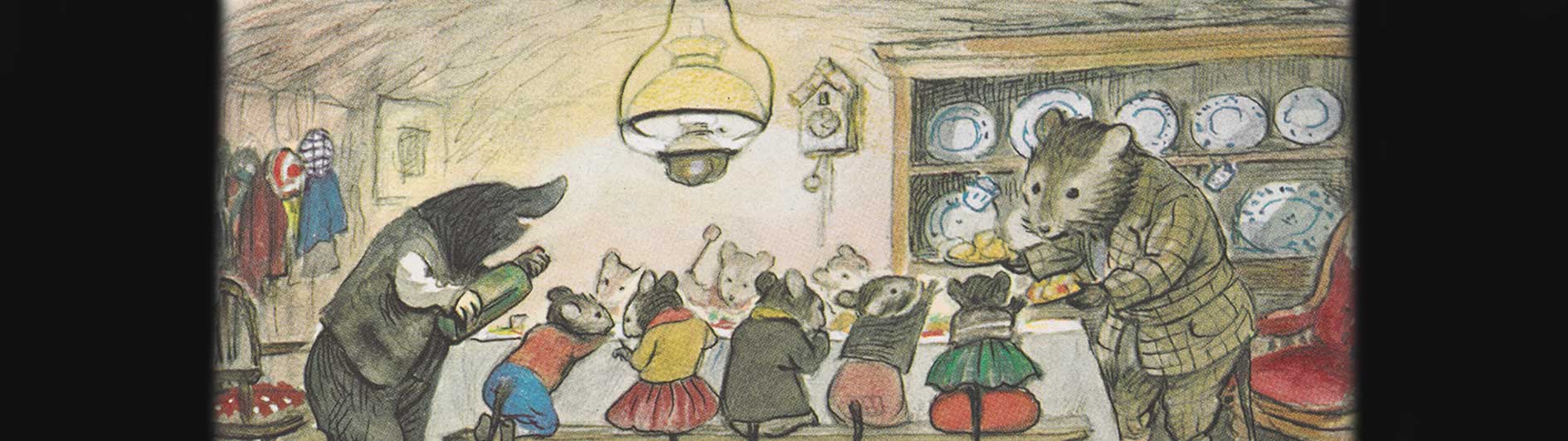

The book appeared in October 1908, and despite cool reviews was an almost immediate commercial success. It has since sold millions of copies. Though the work was initially published without illustrations, in 1930 the artist E H Shepard was commissioned to produce artwork, and his witty, characterful images have become almost as admired as The Wind in the Willows itself.

Synopsis

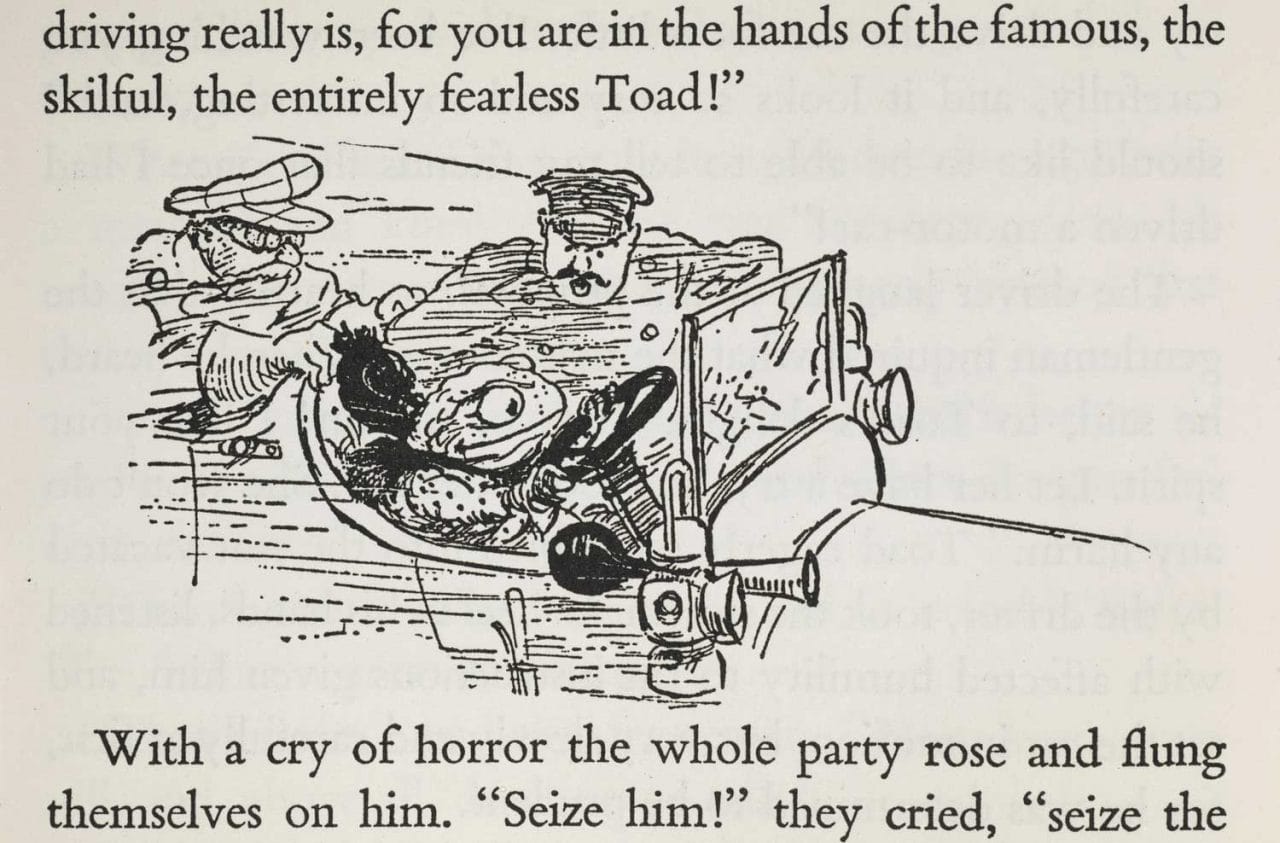

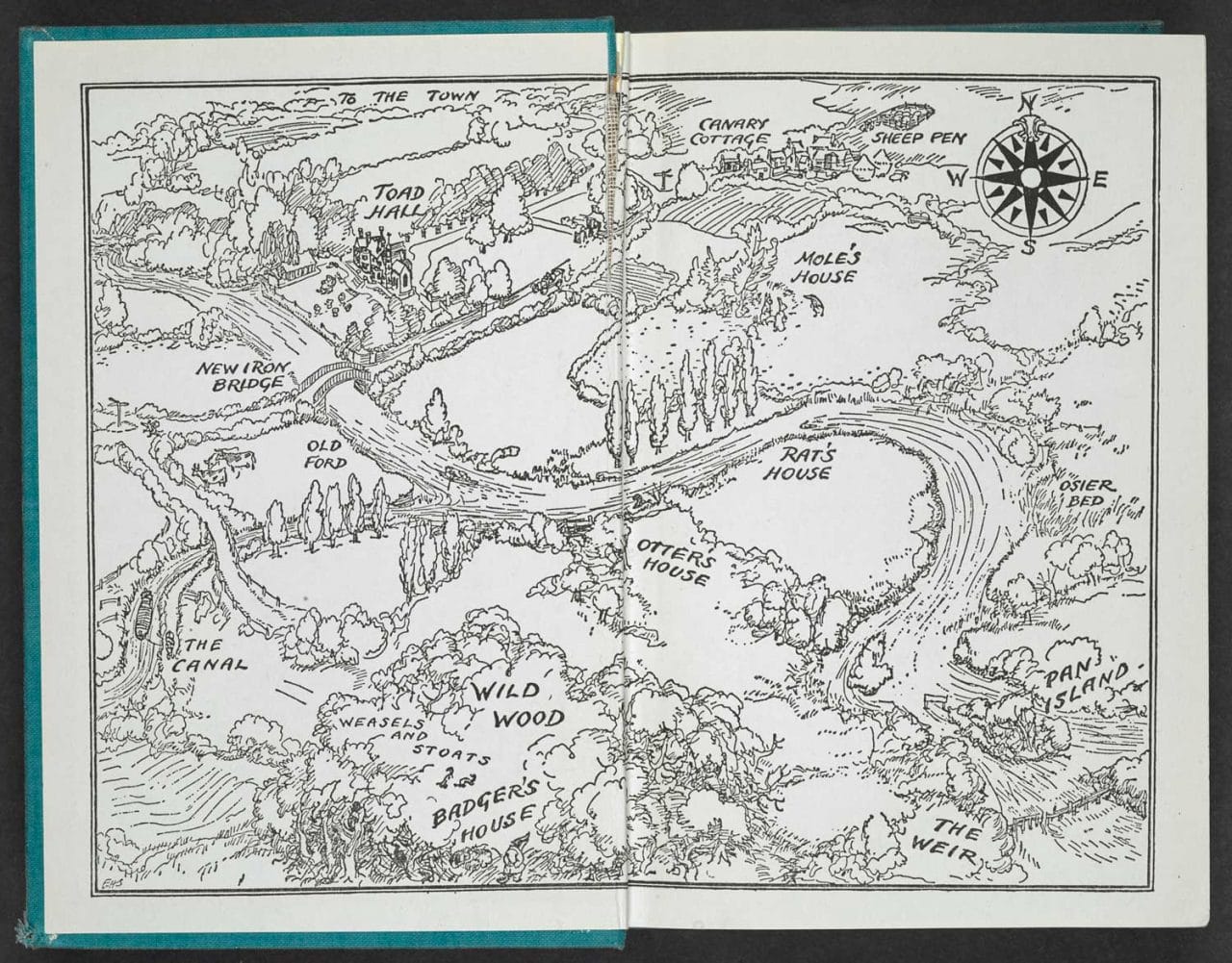

The basic story is straightforward – the nervous, stay-at-home Mole yearns to break free, and decides to go on an adventure. At the river, he becomes friends with Ratty (in fact a water vole), who offers Mole a jaunt in his rowing boat with the famous insistence that ‘there is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing around in boats’. En route, Mole and Ratty pay a call on the brash and roguish Toad of Toad Hall and travel to the Wild Wood in search of the wise but elusive Badger. Toad’s adventures are particularly colourful: obsessed with cars despite his terrible driving skills (he proudly testifies that he has crashed no fewer than seven vehicles), he is placed under house arrest for his own good by Ratty and Mole, but escapes after fooling Ratty into thinking he’s mortally ill. He subsequently steals another car after which he’s arrested by the police and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Once again he breaks free from his captors, this time disguised as a washerwoman. Back on the road, he has a series of wild exploits – ‘travel, change, interest, excitement!’ he cries – before the characters are happily reunited.

Enduring appeal

What makes The Wind in the Willows enduring is not only its deft reworking of classic narrative tropes – Mole’s quest, Toad’s comeuppance – but its glimpses of much more mature themes. Some critics have been struck by the book’s nostalgic, almost religious depiction of English rural life, rendered by Grahame in warmly evocative language and clearly modelled on the Thames Valley landscape that he knew intimately. Others have pointed to the way in which it emphasises the fragility of that landscape, rudely invaded by Toad’s new-fangled automobiles and under threat from malign social forces. In one of the book’s most arresting scenes, a band of evil Stoats, Weasels and Ferrets take over Toad Hall in a kind of anarchist revolution.

Other readers have noticed the vein of sharp social satire that runs through the book – Toad an archetype of the spendthrift landowner with more money and hobbies than sense, while Mole is an image of the quiet, unassuming middle-class Englishman. As the critic Peter Hunt points out, while The Wind in the Willows was written with children closely in mind, Grahame felt it was also a work for ‘those who still keep the spirits of youth alive in them’. He later added that although many readers loved the book, ‘they did not even notice the source of all the agony, all the joy’.

Kenneth Grahame: banker, writer and dreamer

Grahame’s own childhood was far from happy. His mother died when he was five, a loss which drove his father to alcoholism, and the family was brought up largely by Kenneth’s uncle and grandmother. The young Kenneth was a sickly child, but nevertheless did well at school in Oxford, and had every reason to expect he would go on to study at the university. Yet to his lasting shame his uncle refused to pay the fees, and he was forced to get a job. He joined the Bank of England in London in 1879, and remained there until his retirement in 1907.

For those three decades he lived what was essentially a double life: dutiful bank employee during working hours, writer and dreamer by weekend and night. He threw himself into literary activities, and began to publish light short stories in London periodicals.

Even in his early work Grahame exhibited an eye for childhood subjects, writing a number of nostalgic stories about a group of orphaned children that echoed his own early life. More tales were collected in The Golden Age (1895) and Dream Days (1898), which made Grahame’s name. In 1897 he met Elspeth Thomson, who had close connections to the artist John Tenniel and was a friend of the poet Alfred Tennyson. Two years later, they married, and in 1900 their only son, Alastair, was born. Nicknamed ‘Mouse’, he was blind in one eye and had a severe squint, and seems to have had learning difficulties. Nonetheless, his doting parents believed that he harboured brilliant talents.

In 1906 Grahame had been involved in an altercation at the Bank, when a mentally ill man had attempted to shoot him; despite being physically uninjured, Grahame decided to resign in June 1907 and devoted the rest of that year to turning his notes into a book he initially called The Wind in the Reeds.

A sad end

Despite its enormous success, The Wind in the Willows has a bleak coda. Grahame always denied that he was a ‘professional writer’, and completed little other literary work. Much of his and Elspeth’s energies were taken up with Alastair, who as he grew up became ever more cut-off from life, seemingly unable to live up to his parents’ exaggerated expectations. Having dropped out of both Rugby and Eton, he was eventually sent to Christ Church College, Oxford, where he struggled academically and was profoundly unhappy.

In May 1920, during his second year at Christ Church, Alastair walked onto a railway line a few days before his 20th birthday and was killed; though the coroner recorded a verdict of accidental death, the circumstances point to suicide. He was buried in Holywell cemetery, Oxford. In 1932, having cleared out the family house and spent his last years travelling extensively around Europe with Elspeth, Grahame died and was interred next to his beloved son. In the intervening time, he had written almost nothing else of note.

Written by: Andrew Dickson

The text in this article is available under the (Creative Commons License).