Moral and instructive children’s literature

Professor M O Grenby looks at the ways in which children’s literature of the 18th and 19th centuries sought to improve its young readers, combining social and moral instruction with entertainment.

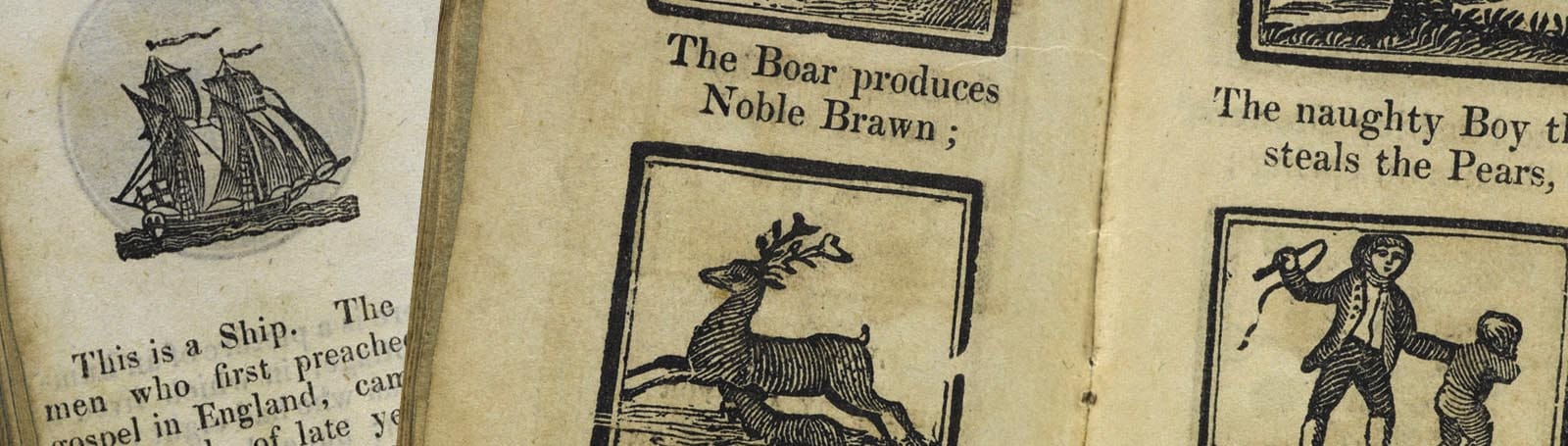

Those who write children’s books have always thought it part of their job to instruct their readers, whether in facts, religion, morals, social codes, ways of thinking, or some other set of beliefs or ideas. From very early on, authors and publishers realised that instruction would be more effective if it were made entertaining, and this sugar-coating approach – ‘instruction with delight’ – became enshrined in children’s literature from around the middle of the 18th century.

The pioneer children’s writers of the 1740s and 1750s were already experimenting with short fictions designed to teach behavioural and ethical lessons: what would come to be known, towards the end of the century, as ‘moral tales’. One of the first was The Christmass-Box, published by M. Cooper and M. Boreman in 1746 and written by ‘Mary Homebred’ (a pseudonym for the novelist Mary Collyer). It included stories three or four pages long whose lessons can be easily summarised. In ‘The History of Miss Polly Friendly’, for instance, Polly accidentally breaks a set of china and hides the pieces in the coal cellar but, when the breakage is blamed on a servant, admits her fault. Virtue becomes a habit and she grows up to marry an alderman, eventually becoming the Lady Mayoress. ‘The influence that stories of the like kind … have had upon my own Children,’ wrote the author in her preface, ‘is a great Inducement to me to make these Publick’. This kind of declaration that a published book had sprung out of maternal duties was typical. Men wrote moral tales too, and there was definitely money to be made from them. But it was a genre associated with women, which probably partly accounts for its lowly literary status.

Learning from your own mistakes

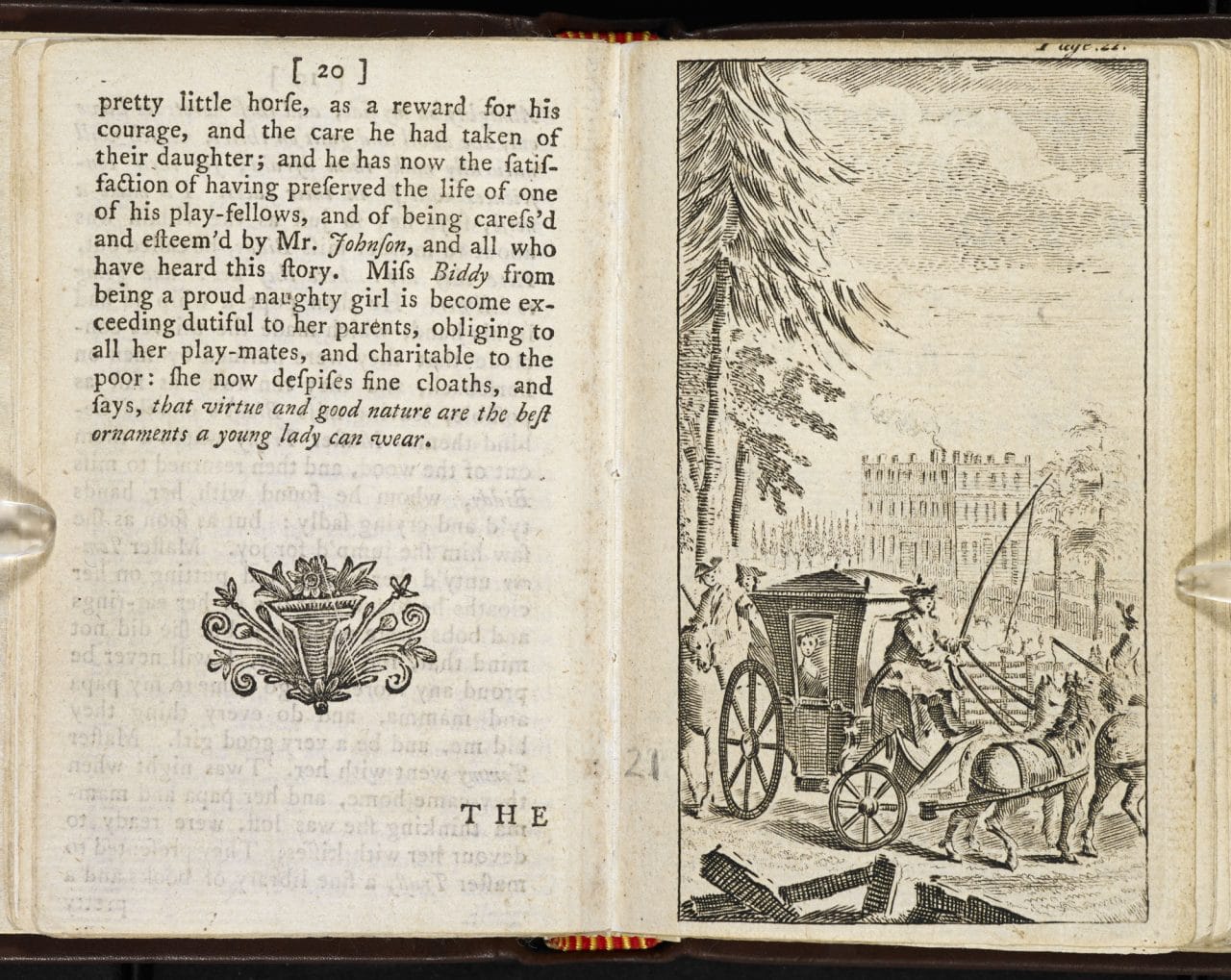

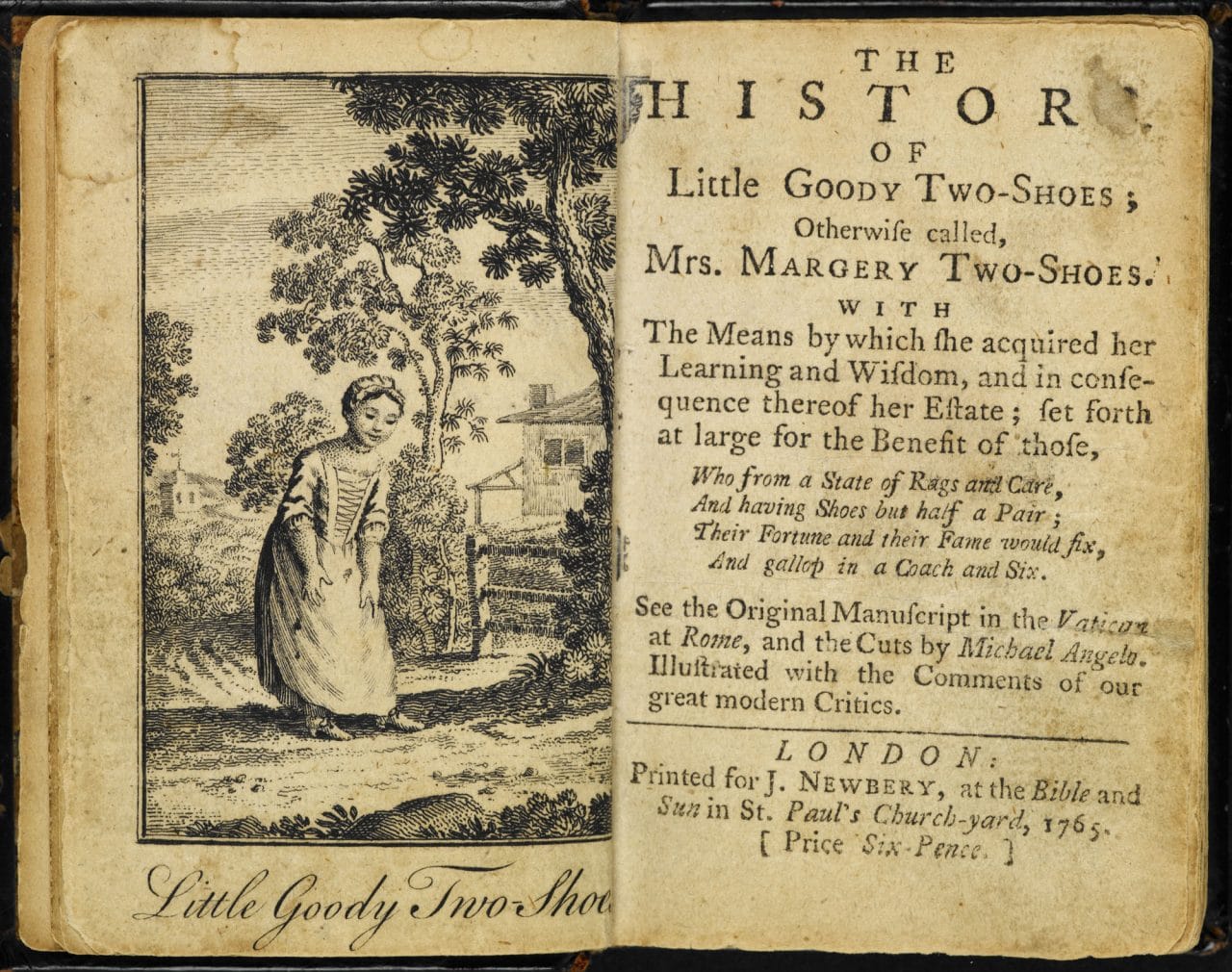

Moral tales became longer and often more sophisticated. Sarah Fielding’s The Governess (1749) was an early school story, but had a structure similar to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, each of the schoolgirls giving an account of her own life then telling a moral story for the education of the whole class. ‘An Adventure of Master Tommy Trusty and his Delivering Miss Biddy Johnson, from the Thieves who were going to murder her’ (in The Lilliputian Magazine, 1751-52) was a novel in miniature, warning against the childish vanity of Biddy who was kidnapped because she insisted in walking around town in fine clothes and jewellery. The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes (1765), also published by John Newbery, was perhaps the first full-length novel for children, telling how the young Margery became an orphan, how she educated herself and then others, how she ran a school, foiled an attempted burglary, exposed a fake ghost and, eventually, married the local landowner.

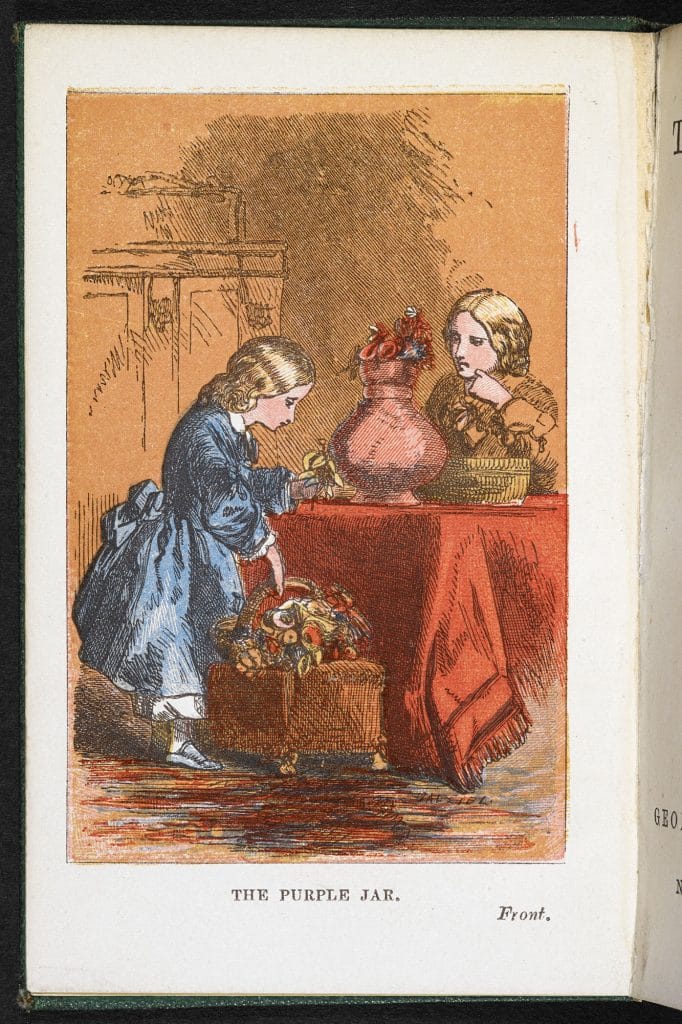

By the end of the century, in the hands of skilful writers such as Maria Edgeworth, the moral tale could introduce the reader to psychologically complex characters put in situations in which there wasn’t always a clear moral path to be taken. A famous example is Edgeworth’s ‘The Purple Jar’, first published in The Parent’s Assistant (1796). It depicts the agonies of indecision of Rosamond, a girl who wants to do right but, when her mother refuses to advise her, chooses (foolishly) to buy a gaudy vase rather than the new shoes she will soon need. The vase Rosamond buys turns out to be full of a foul-smelling purple liquid which, when poured away, leaves her with only a rather dull glass jar. This demonstrates why the moral tale was so successful: carefully designed narratives could allow characters, and through them the readers, to learn by their own mistakes, rather than by direct authorial admonition.

Depicting middle-class values

Indeed, most moral tales were set in familiar environments – middle-class homes, nicely kept gardens, well-to-do villages and cities – which would maximise the reader’s identification with the characters and their dangers and dilemmas. The values being taught were generally familiar too: commercial qualities like hard work, thrift and honesty; moral virtues like solicitude for others; social virtues like politeness, charity and obedience to parents; and a rationality which disdained fear of the dark or ghosts and rejected sentimentality or excessive emotion. In the early 19th century, the Evangelical revival led to an increasing number of religious tales, many of them published and distributed by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge or the Religious Tract Society. The most famous was probably Mary Martha Sherwood’s The History of the Fairchild Family (1818-47). Even with all its overt religiosity, The Fairchild Family could entertain and perhaps comfort the reader with its familiar domestic setting, its close study of parent-child relationships, its strong central characters, and the small predicaments they find themselves in.

Romantic backlash

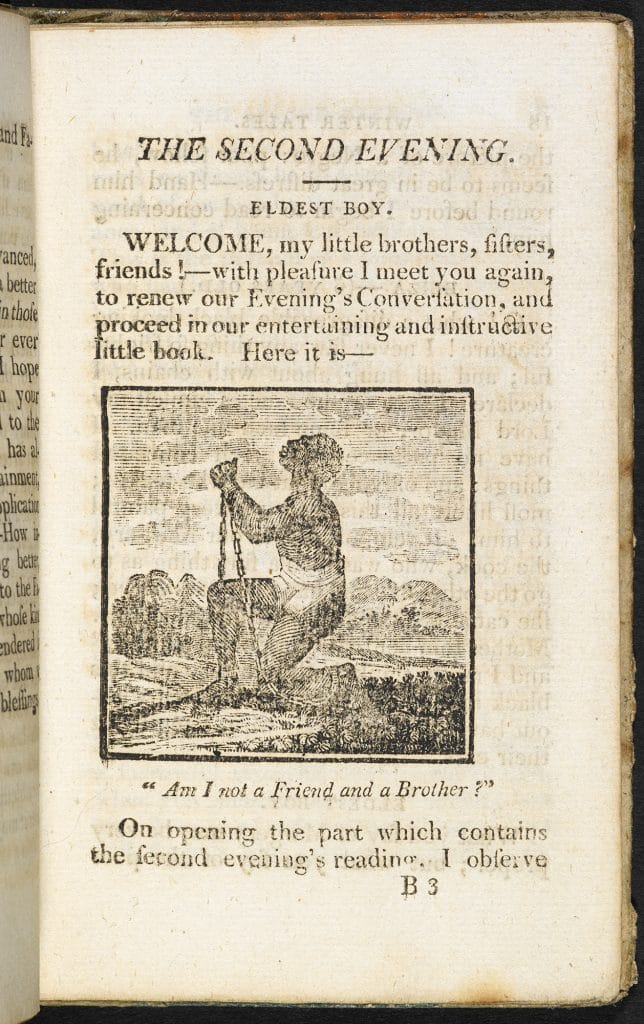

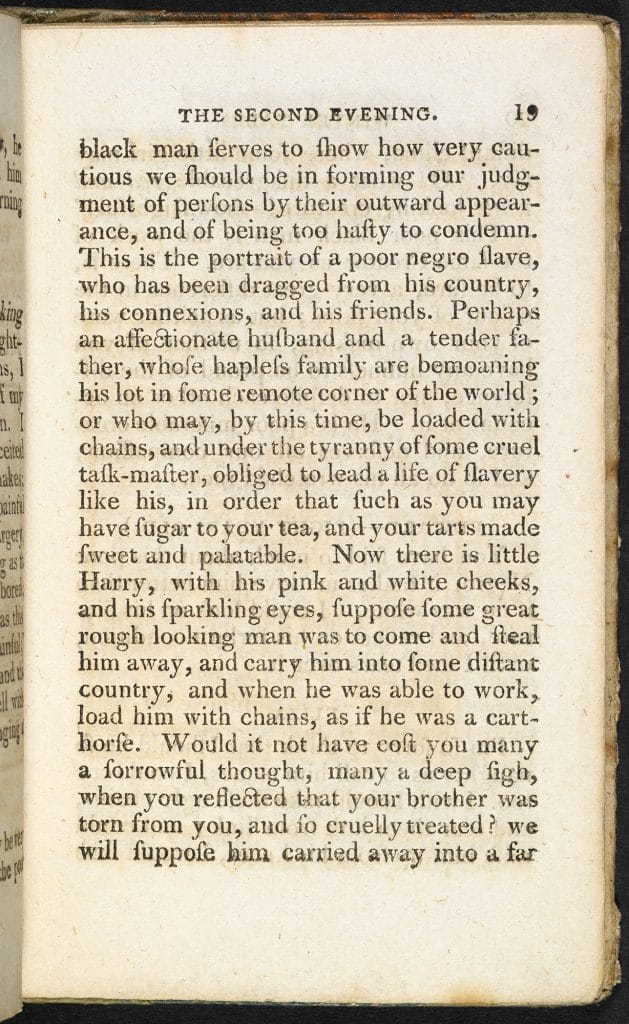

Romantic writers, in the early 19th century, found it expedient to make the moral tale the butt of their complaints about what they saw as the increasingly utilitarian direction society was taking. This kind of literature, they argued, suppressed imagination and true morality. In 1808, for example, Samuel Taylor Coleridge lectured against ‘moral tales where a good little boy comes in and says, Mama, I met a poor beggarman and gave him the sixpence you gave me yesterday. Did I do right?’ Such books, he said, ‘do not teach goodness – but if I might venture such a word – goodyness’. Writing in 1823, Sir Walter Scott agreed that when children read moral tales, ‘their minds are, as it were, put into the stocks’ and he objected to the way ‘the moral always consists in good conduct being crowned with success’. ‘I would not give one tear shed over Little Red Riding Hood’, he went on, ‘for all the benefit to be derived from a hundred histories of Jemmy Goodchild’.But in fact, these critics hugely exaggerated the dichotomy, and the line between the moral and instructional tale, and the fairy tale and fantasy writing, was very blurred. Moral tale authors were not above employing fairies and fantasy elements, particularly talking animals, as in Dorothy Kilner’s The Life and Perambulations of a Mouse (1783) or Sarah Trimmer’s Fabulous Histories (1786) about a family of robins. There is plenty of evidence that actual children enjoyed moral tales every bit as much as the more traditional stories that the Romantic poets claimed to prefer. The moral tales could often be very radical too, in stylistic, substantive as well as political terms. They pioneered science education for instance, for girls as well as boys, and many moral tales decried the slave trade. The Happy Family; or, Winter Evenings’ Employment (1801) was one, an older brother explaining slavery to his six-year-old sister and urging a boycott of the sugar that keeps the slave trade going. ‘Perhaps if older Christians than we were to come to a resolution to break the fetters, to emancipate and kindly raise up these poor afflicted fellow-creatures, who are so sorely burthened,’ he tells her, ‘they would feel a more exquisite sensation that they had ever before experienced.’

The endurance of didactic children’s literature

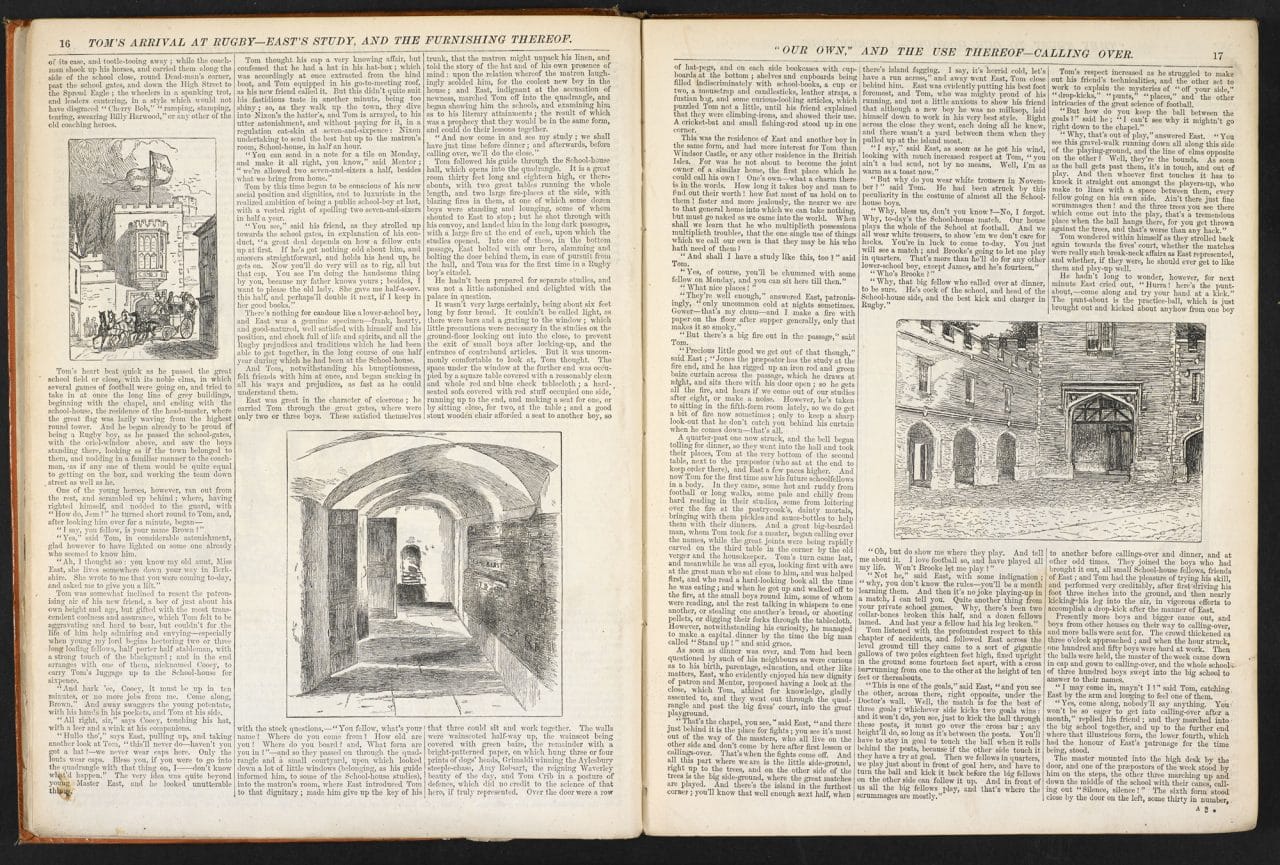

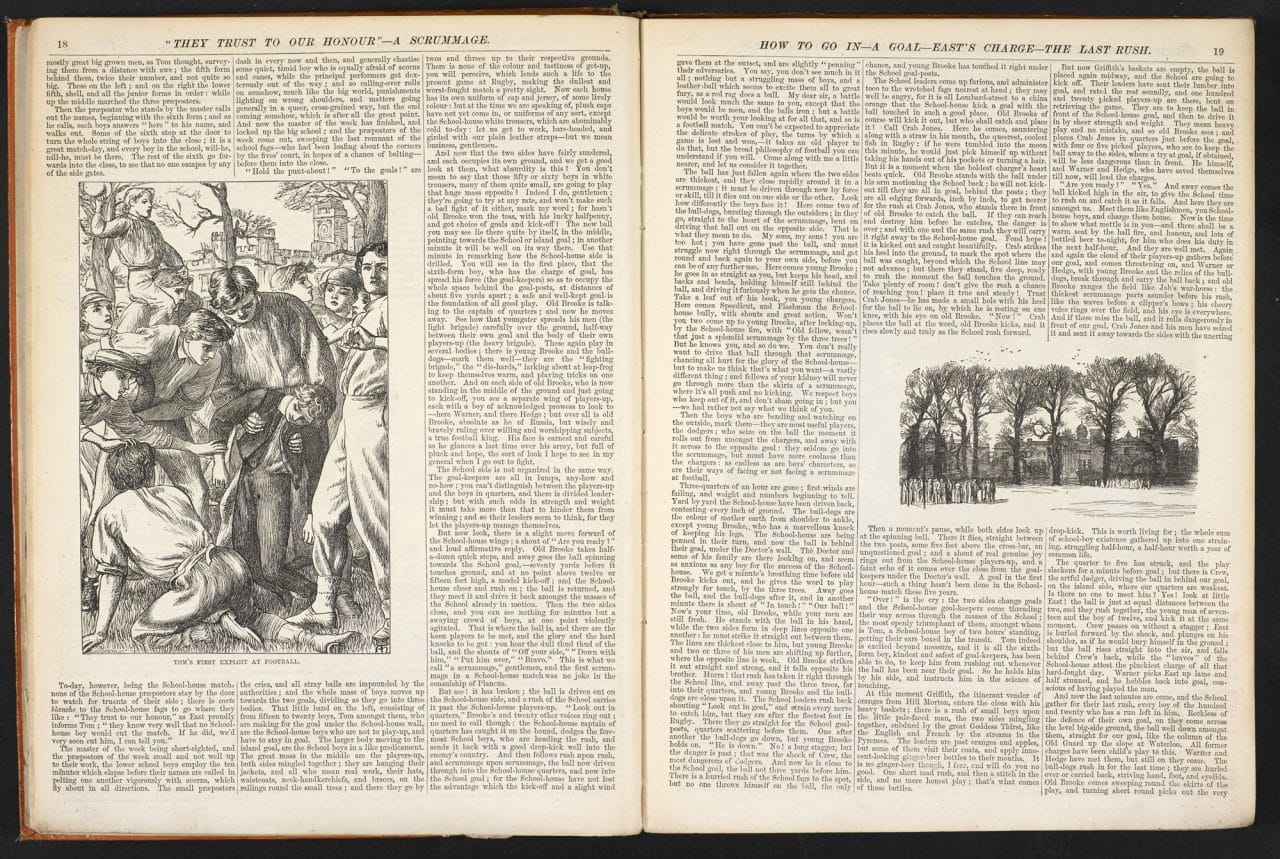

Despite the poets’ disdain, the moral tale did not die out in the 19th century. It continued alongside the revival of the fairy tales tradition and the new fashion for fantasy literature. Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), for instance, was not so very different from Fielding’s Governess, written a century before, teaching a certain kind of morality in a school setting. Mrs Ewing’s Jackanapes (1879) was a moral story set on an imperial battlefield. Indeed, it might be said that the moral tale entered the mainstream. Charlotte Yonge’s The Heir of Redclyffe (1853) was not written as a children’s book, though it was widely read by the young, but in classic moral tale style, it used an affecting narrative to ram home to its many readers the virtues of patience, devotion and integrity. By the start of the 20th century, this kind of moral literature was still being mocked, in E. Nesbit’s The Wouldbegoods (1901) for instance. But had the moral tale not been a common feature of many children’s lives, that mockery would have had no purchase. Despite the flowering of fantasy literature, instruction was just as important a part of children’s literature in the 20th century as it had been at its origins 200 years previously.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: M O Grenby

M O Grenby is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies in the School of English at Newcastle University. He works on 18th-century literature and in particular on the early history of children’s books. His published works include The Anti-Jacobin Novel, The Edinburgh Critical Guide to Children’s Literature and The Child Reader 1700-1840, and he co-edited Popular Children’s Literature in Britain and The Cambridge Companion to Children’s Literature.