The Pickwick Papers and the making of Charles Dickens

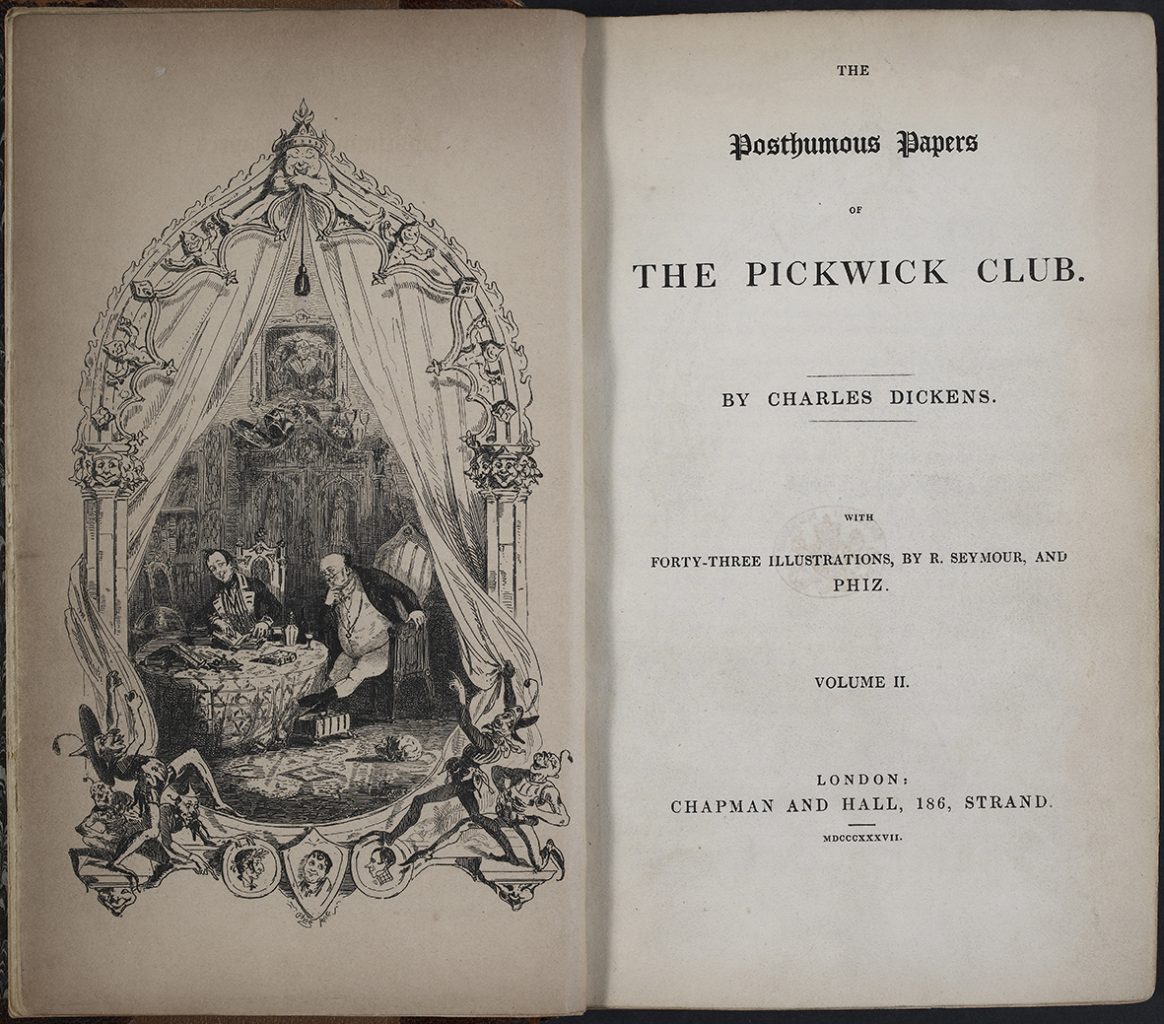

For the first 20 months of its extraordinary career, the book that the world now knows as The Pickwick Papers – the most popular work of British fiction in the 19th century, and a comic masterpiece that in a very real sense made its author’s name – did not look much like the imposing brick of a novel that generations of readers have since loved.

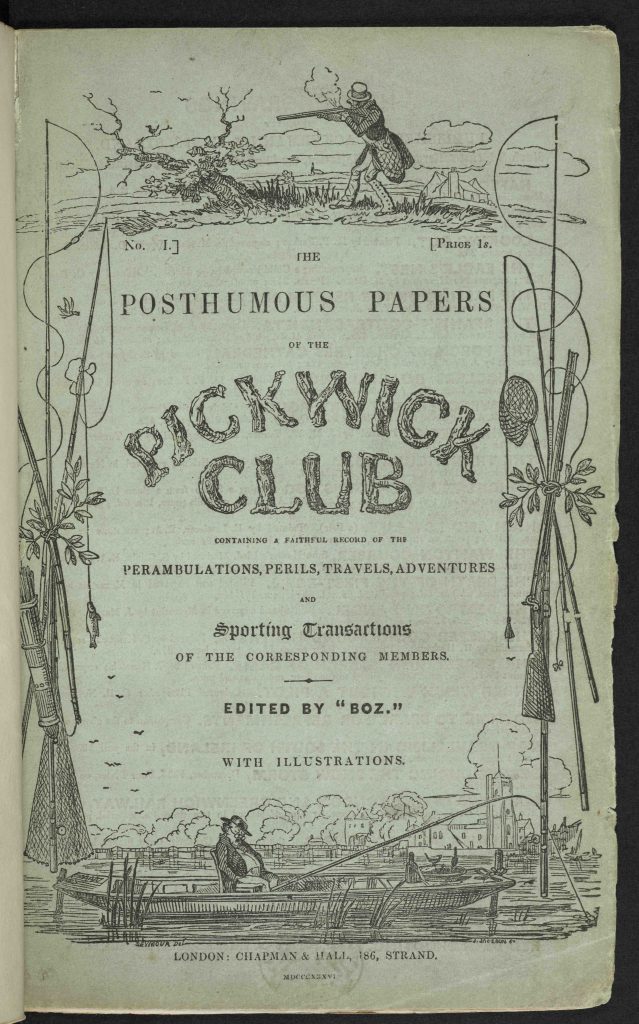

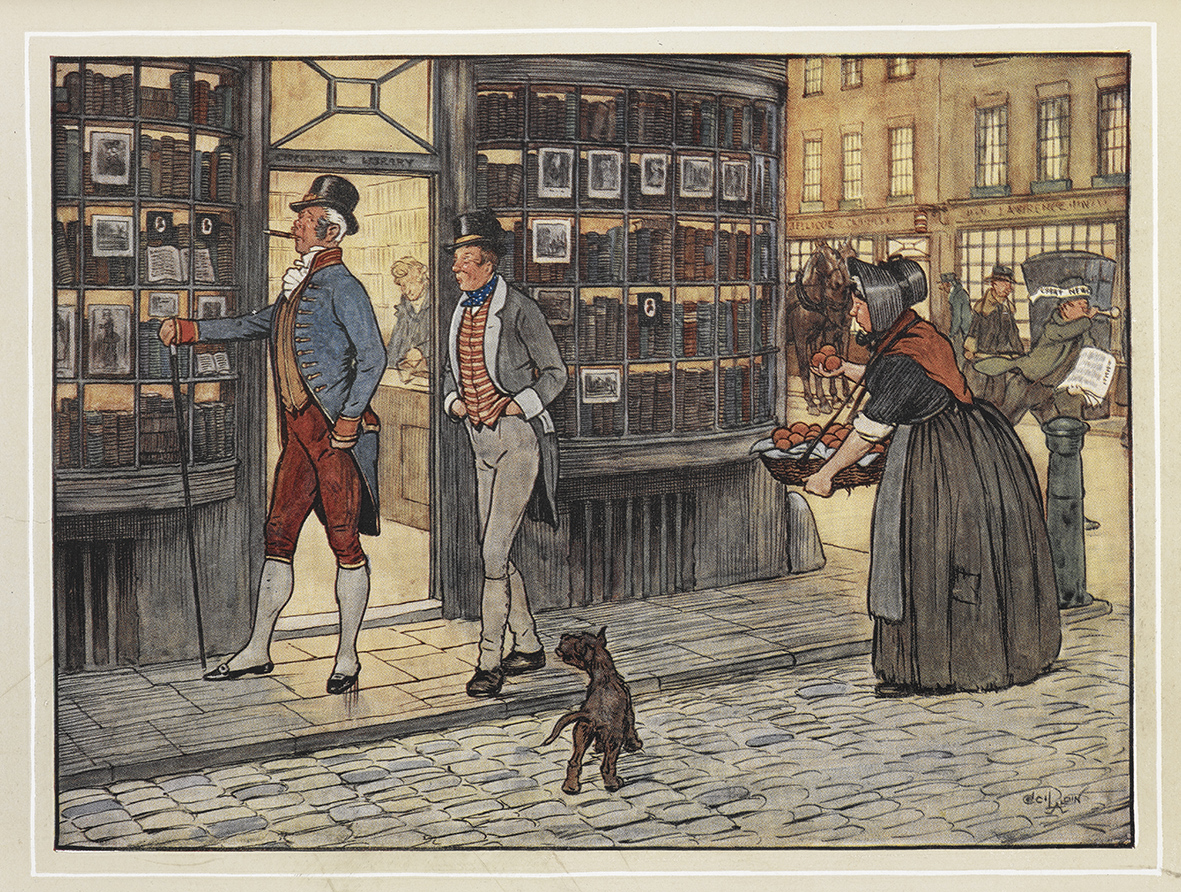

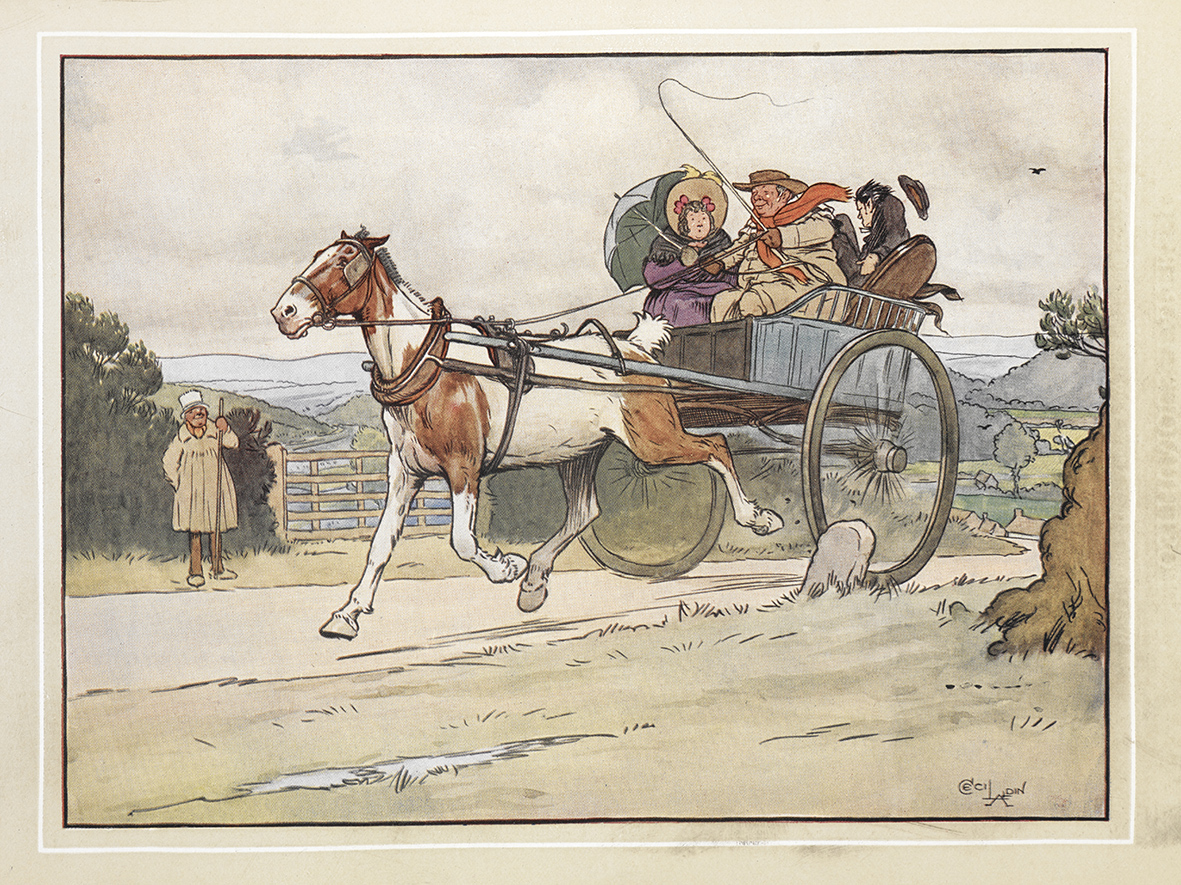

That much is clear from the green cover of the first slender number of the magazine of which Chapman and Hall printed 400 copies in March 1836. Priced at a shilling, it was designed to invite casual judgements and then to undercut them. The log lettering of the Pickwick Club, the fishing rods around the border, the sketch of the snoozing angler on calm waters in the foreground and the small bird apparently untroubled by the discharge of a hunter’s gun seemingly too close to give it a chance, promised contemporary readers familiar with such recent titles as R S Surtees’s fox hunting stories The Jaunts of John Jorrocks, more comic ‘Sporting Transactions’ of the kind that the man who had the idea for these adventures, the cartoonist Robert Seymour, wanted to sketch.

But the smaller print hinted at other targets, closer to the heart of Seymour’s junior partner, the 24-year-old parliamentary sketch writer and court reporter best known for his own recent Sketches by ‘Boz’ (1836). On the verge of marriage, and in need of an income, Charles Dickens seized the chance (declined by at least two other more established writers) to supply a prose frame for Seymour’s pictures.

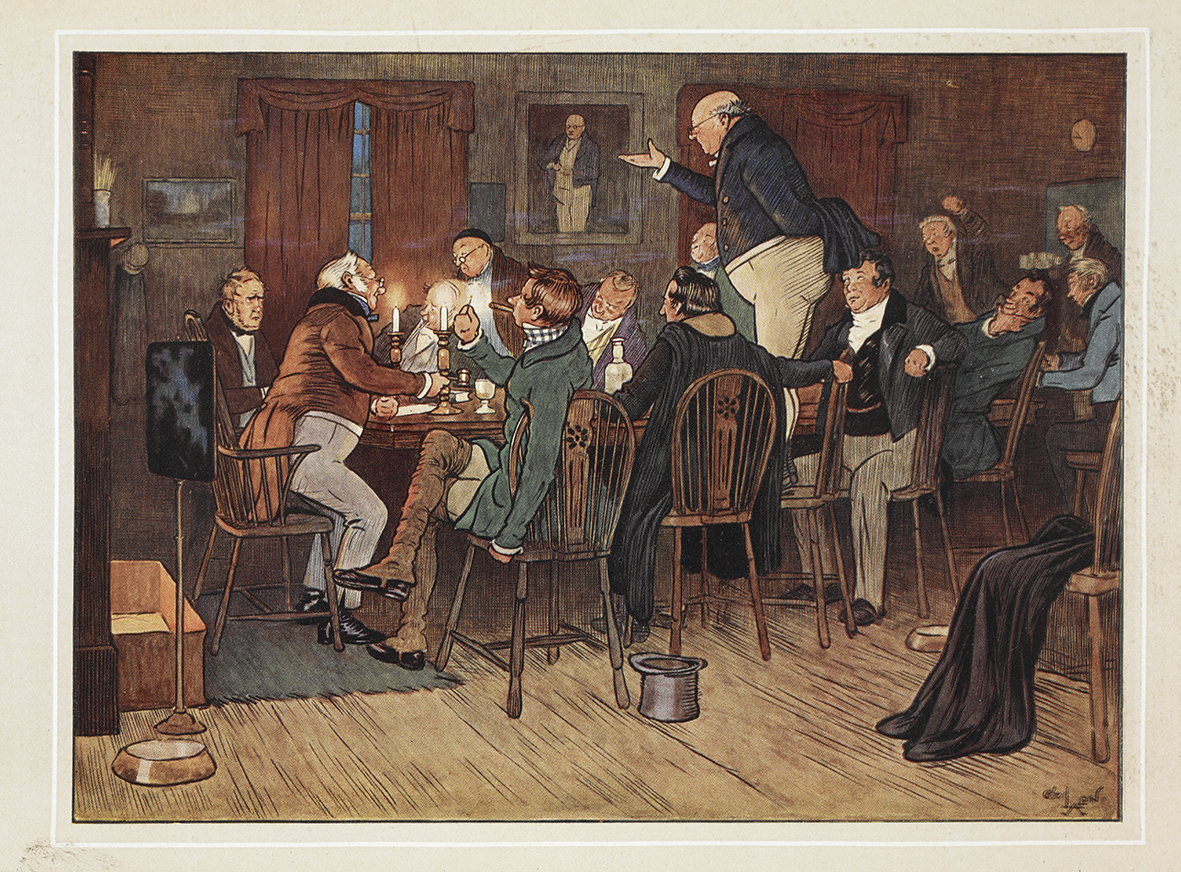

‘The work will be no joke, but the emolument is too tempting to resist’, he wrote to his teenage fiancée, Kate Hogarth.[1] And the contents of that first issue exchanged conventional field sports for a very different variety of ‘Perils and Perambulations’, and set out to use the Club’s ‘corresponding members’ to make a range of increasingly wild jokes, not just at their own expense but in settings a long way from the rural tranquility that might have been expected. The first chapter plunged its readers into the company of a stuffy London club room, where the discussions ‘bear a strong affinity to the discussions of other learned bodies’ – the British Society for the Advancement of Learning on one hand, Parliament on the other. When Pickwick is called a ‘Humbug’, an insult British politicians still use to accuse each other of hypocrisy, tempers are only defused by the charming defence that the word had been used in its ‘Pickwickian’ sense.

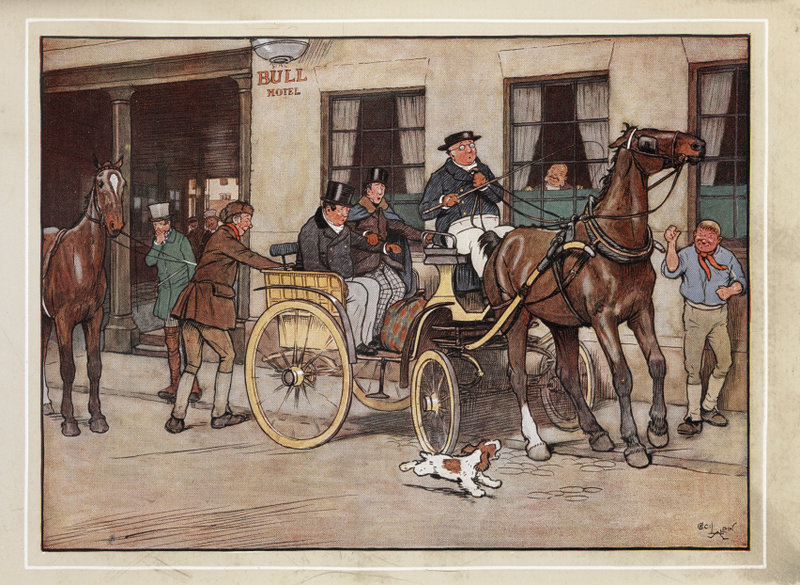

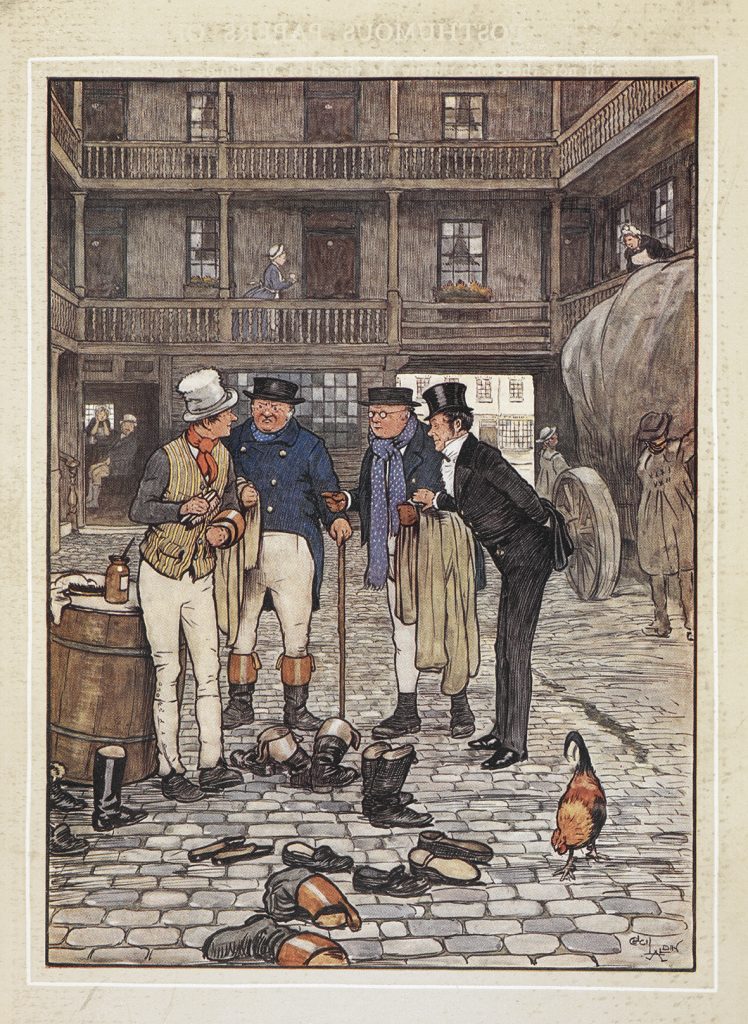

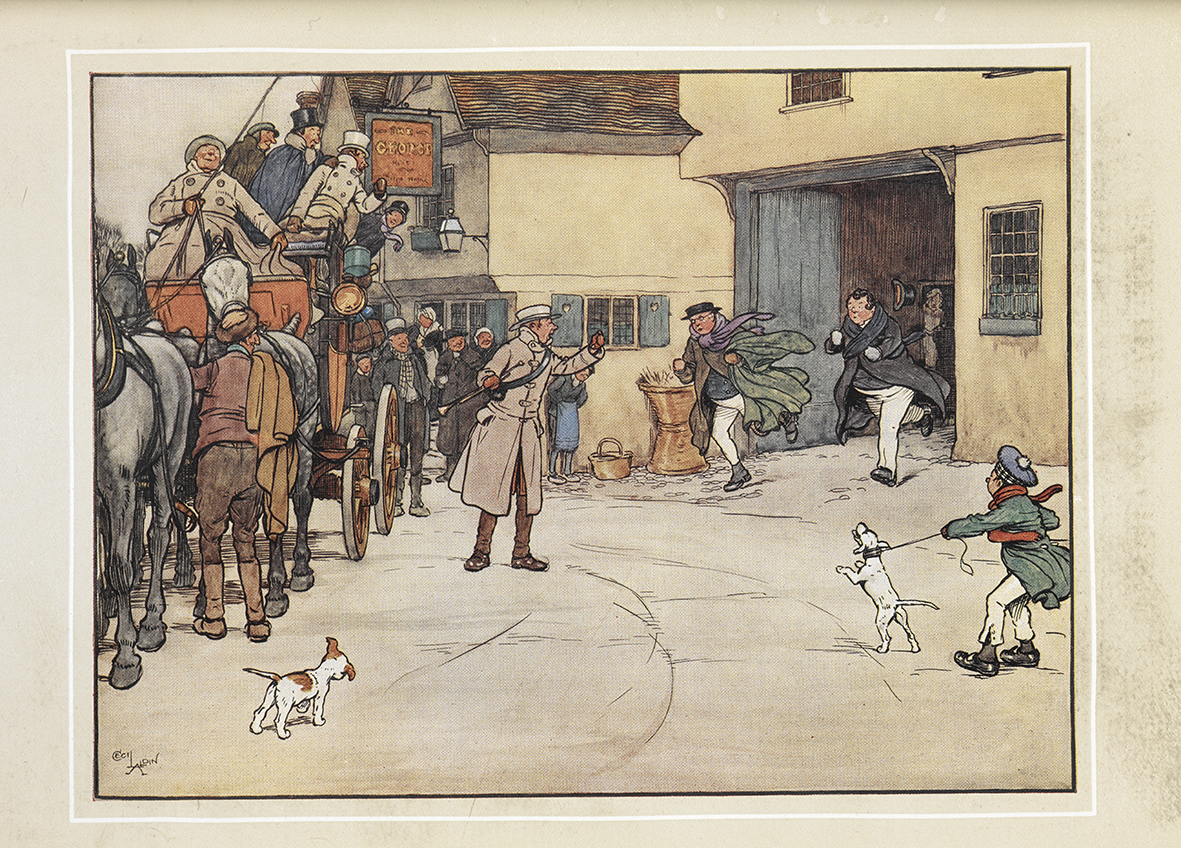

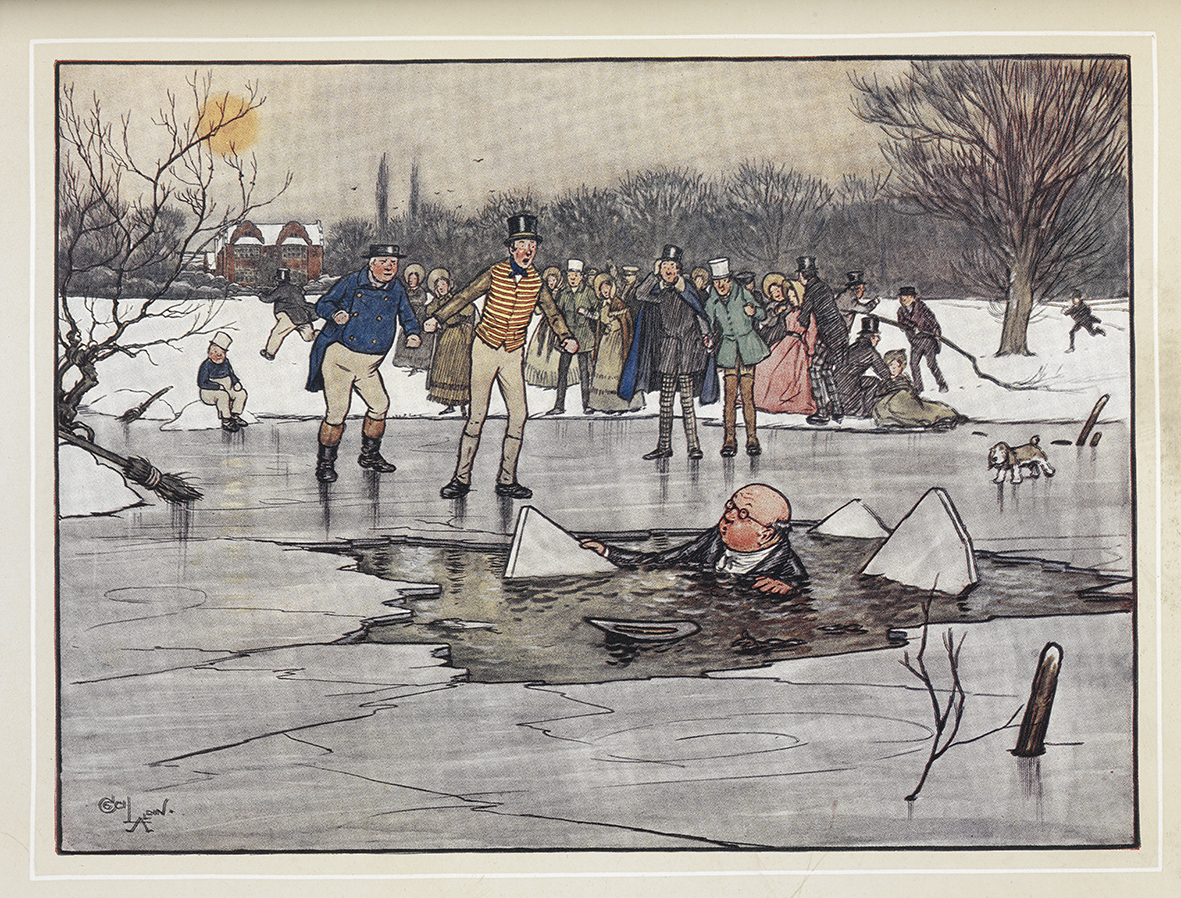

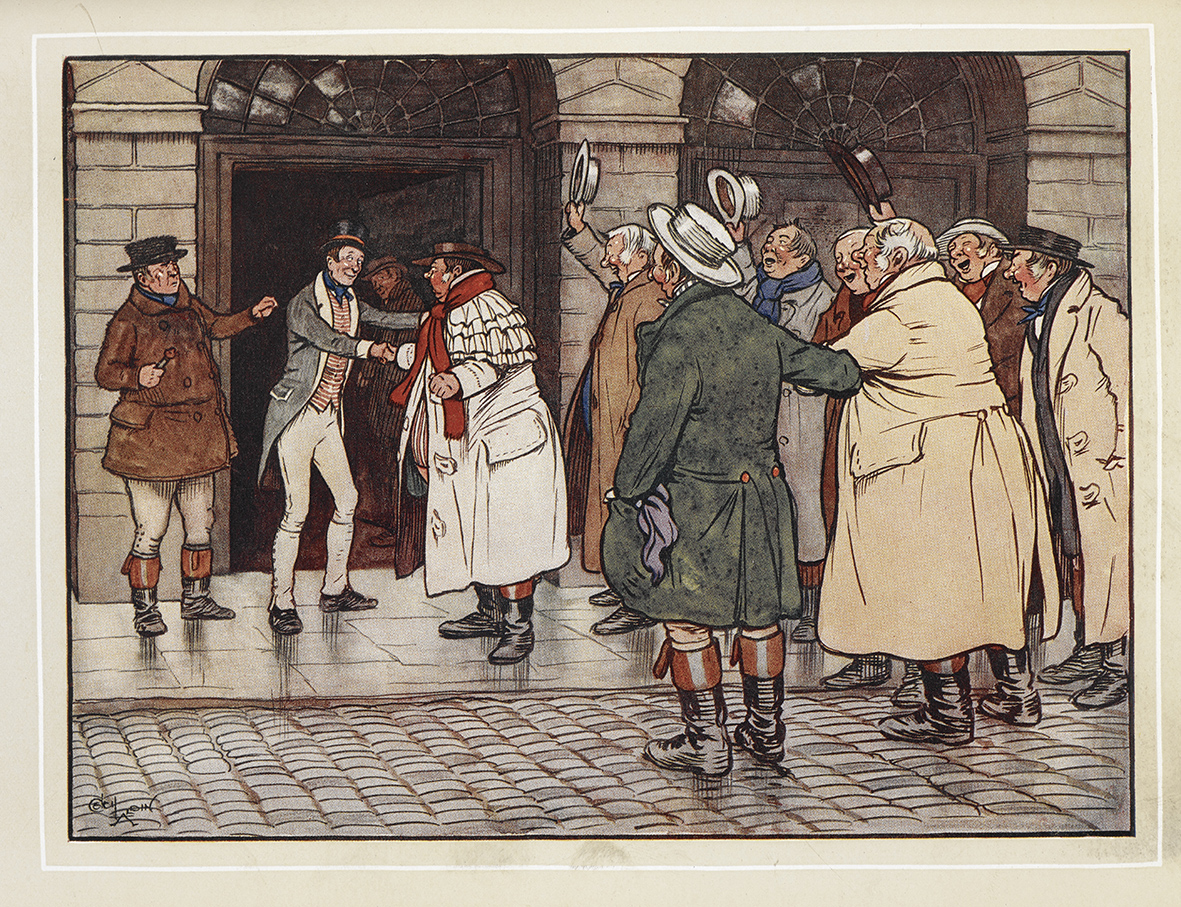

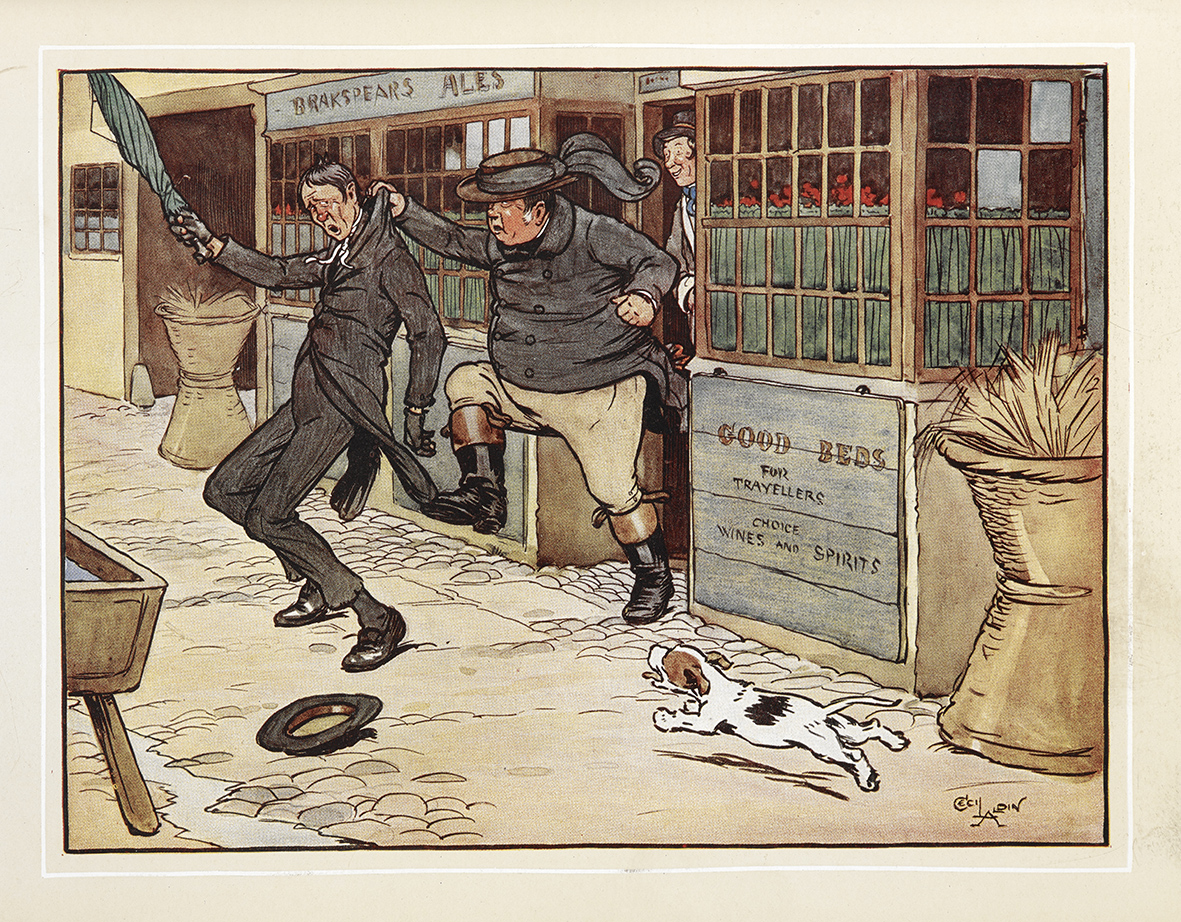

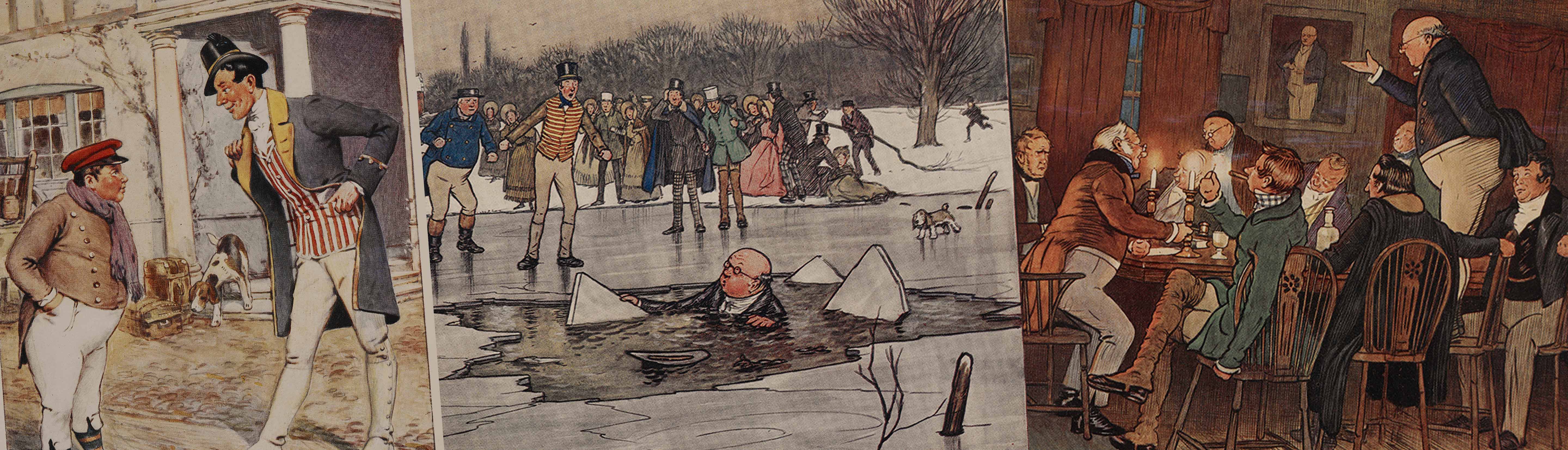

And then the action switches to the streets of London and the Rochester coach. In this world, vividly realised, larger than life and teeming with more tall stories than the portly Samuel Pickwick’s notebook can safely record, neither he nor his companions – the poetic Snodgrass, the amorous Tupman or the one would-be sportsman in the company Winkle – stand a chance of surviving unscathed. A cabman called Sam knocks Pickwick’s hat off and accuses him of being an informer. A crowd surrounds them, roused by ‘a hot-pieman’, who becomes, deliciously, ‘a heated pastry-vendor’ as the temperature of the scene mounts. And even when Pickwick and his friends are rescued from the first of these scrapes by a streetwise fast talker by the name of Alfred Jingle, who speaks almost as fast as Dickens wrote, it isn’t long before Jingle and his accomplice, Job Trotter, are revealed to be scoundrels, determined to exploit every opportunity to live at their expense. Real peril ensues.

What the Pickwickians needed was a real saviour – a companion that Pickwick could trust. After three monthly numbers, the Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club needed one too, in the face of its own crisis: Seymour, bewildered by the twists Dickens had insisted on bringing to his project, had shot himself; sales were falling.

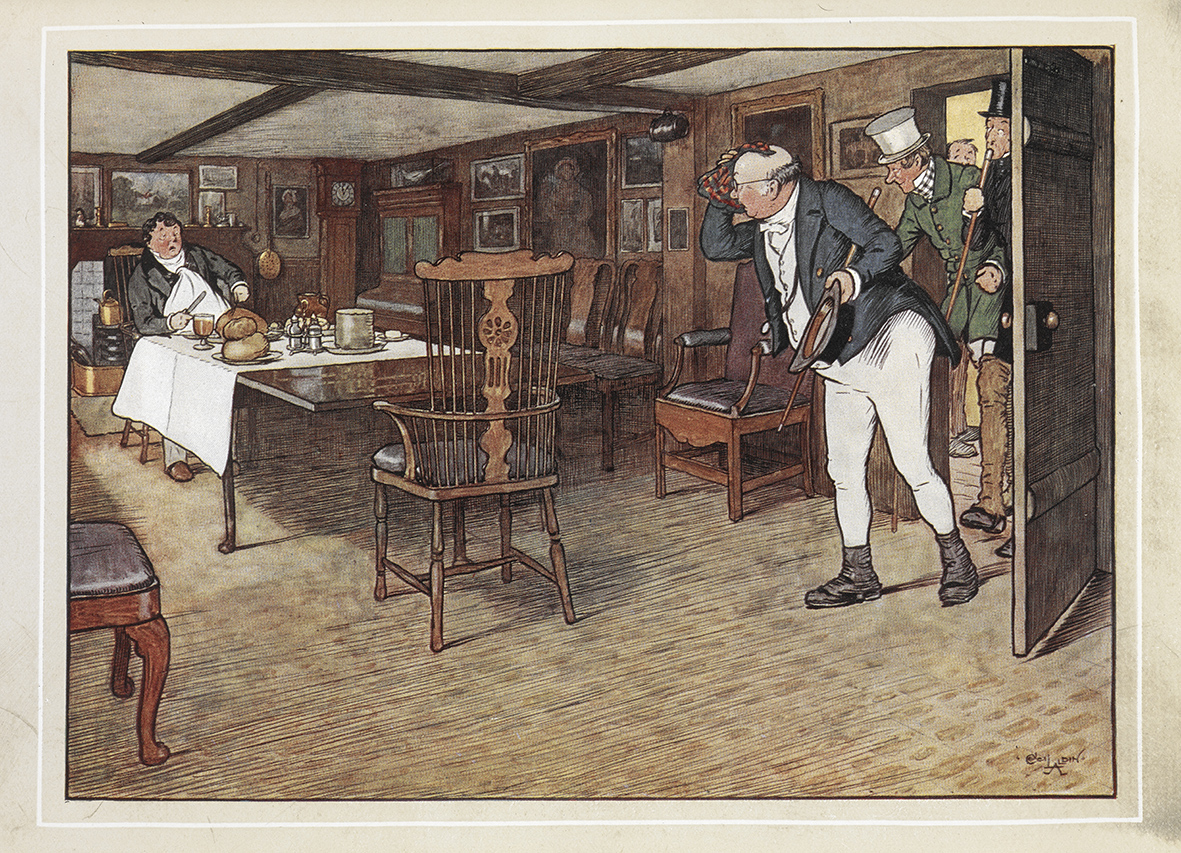

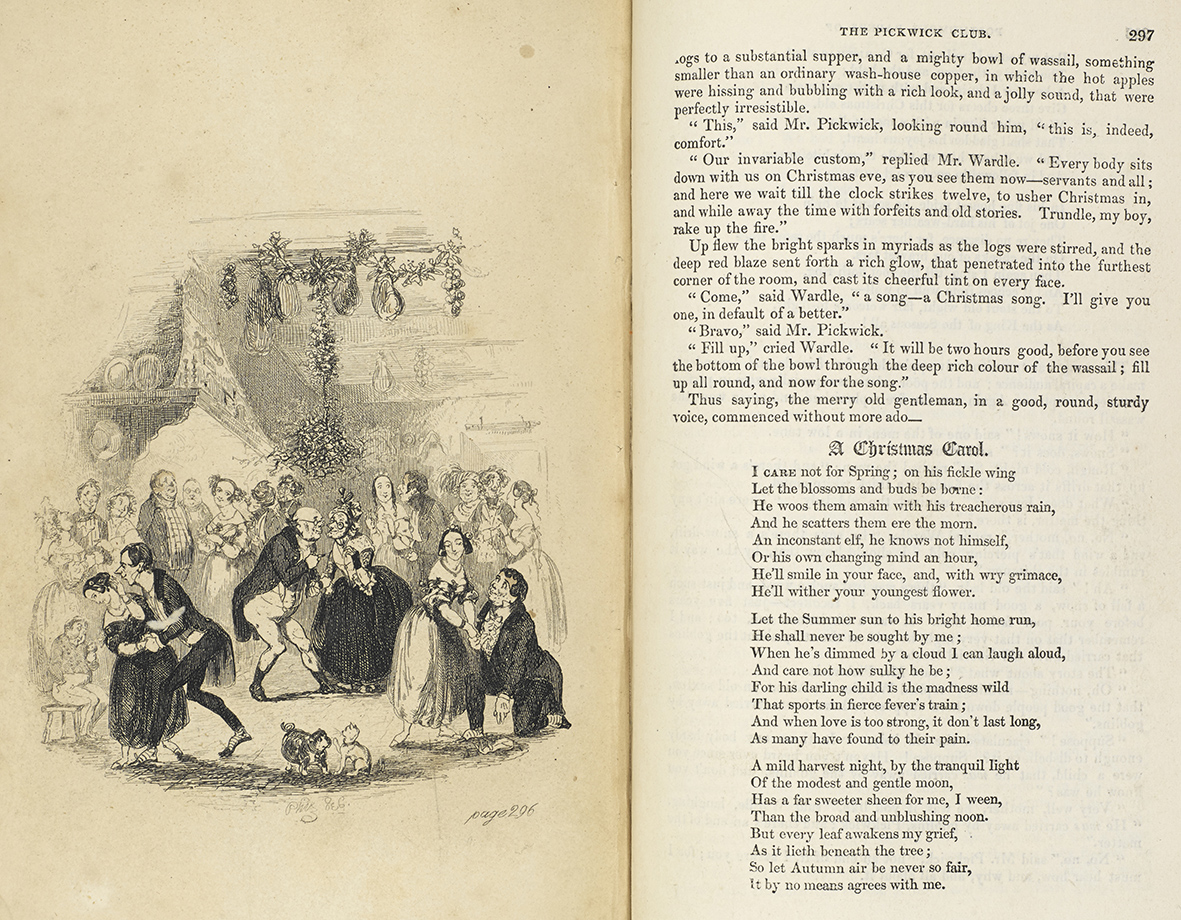

By chapter 19, and the seventh monthly number, the saviour had arrived. And in this manuscript page you can see both him and his creator at work, on an outing to the country that at last delivers the promise of that cover.

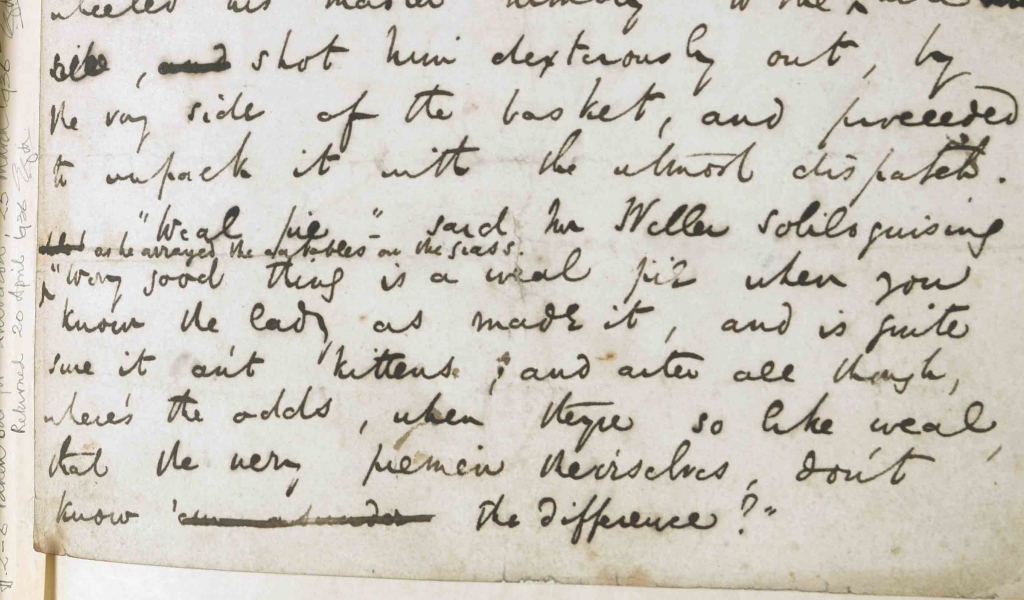

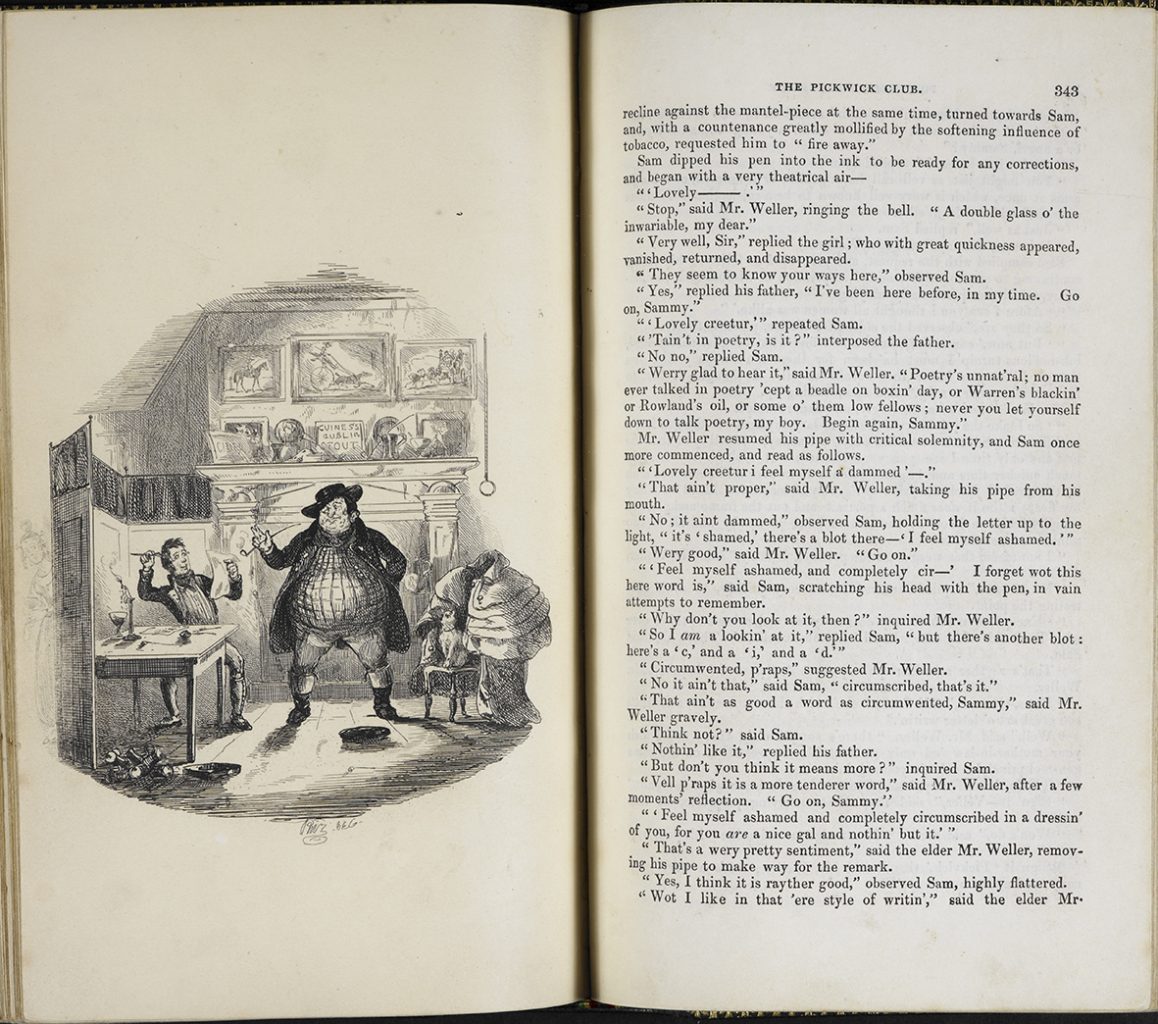

Though Pickwick never did go fishing, his friends are out shooting. Winkle has ‘flashed, and blazed, and smoked away, without producing any material results worthy of being noted down’. Pickwick himself is lamed by an attack of rheumatism sustained in the aftermath of the Eatanswill election he has just observed, but he has been nursed back to health and geniality by the conversation and anecdotes his new servant has told him. Pickwick has even edited one of these stories, which has become the latest of the Pickwick Papers’ many interpolated tales, ‘The Parish Clerk – A Tale of True Love’. Today, 1 September, Sam Weller [2] has wheeled his master in a barrow to the hillside where they will join the shooters for lunch. There, in due course, too much punch will be consumed, with consequences that Sam will need to address. But now Sam is unpacking the picnic basket, and discovering pies. They may be veal, or – as Sam says it – ‘weal’.

‘Wery good thing is a weal pie, when you know the lady as made it, and is quite sure it ain’t kittens; and arter all, though, where’s the odds, when they’re so like weal that the wery piemen themselves don’t know the difference?’

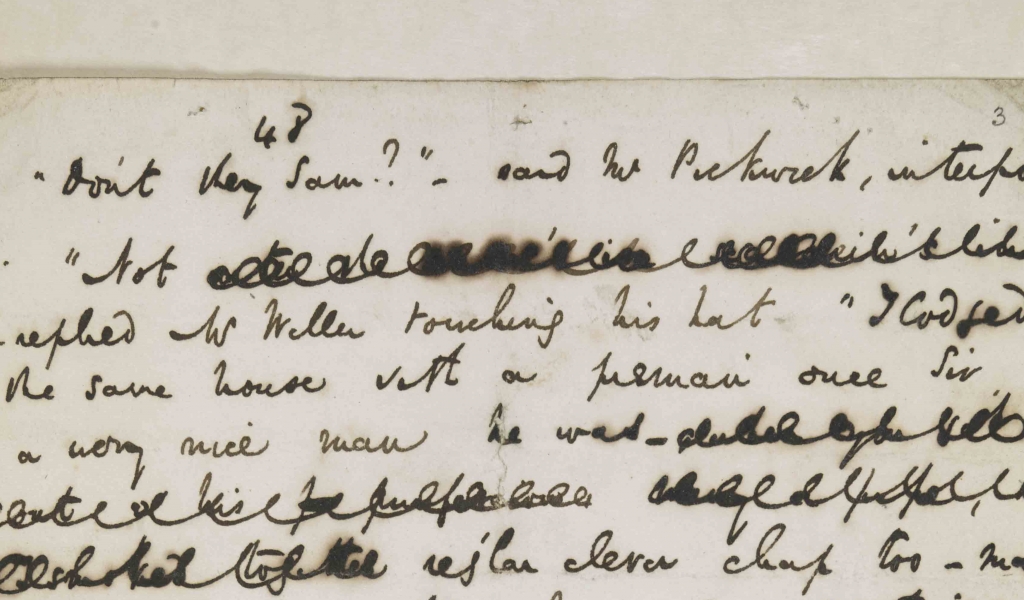

One page of working manuscript is never enough. ‘Don’t they, Sam?’ asks Pickwick, at the top of the next.

Of course, whether or not they really do is beside the point. What matters is the story Sam Weller goes on to tell, of a pieman he once lodged with. This Mr Brooks kept a surprising number of cats, or at least he did until they were ‘in season’, winter, when hot pies were in demand; and then it’s not the source of the meat but what he does with it that counts. With evident relish, Sam first reports Mr Brooks’s proud boast, in defiance of ‘the combination of butchers’, of his versatility with ‘them noble animals’. ‘It’s the seasonin’ as does it … I can make a weal a beef-steak, or a beef-steak a kidney, or any one on ‘em a mutton, at a moment’s notice, just as the market changes, and appetites wary!’ Then Sam adds his own endorsement to Pickwick’s admiration of this ‘very ingenious young man’, which the old gentleman has offered ‘with a slight shudder’. After all, says Sam, ‘the pies was beautiful. Tongue; well, that’s a wery good taste, when it an’t a woman’s’.

No wonder this passage in manuscript would, within a week of his death on 9 June 1870, become a collector’s item for any ‘admirer of the late great and gifted author Charles Dickens’. The new and strange life Dickens managed to give, first as ‘editor’ of these Posthumous Papers, to subjects, whether real or ‘weal’, matters of genuine local history or far-fetched fancy, then as he stirred these episodes into a narrative through the seasons and around the country with Pickwick and Sam Weller at its heart, inspired a whole new generation of readers to share their pleasure.

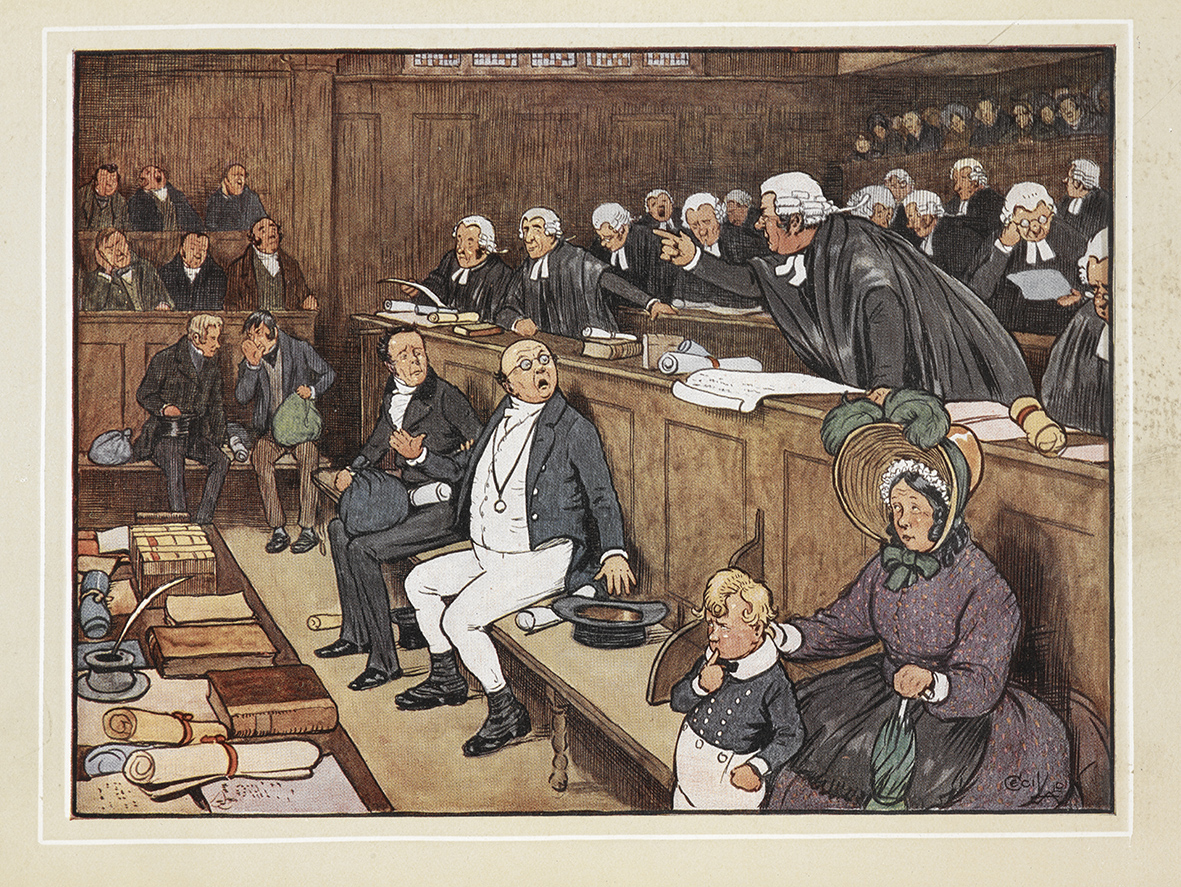

They read Pickwick aloud, as it was written, in drawing rooms and on the street. Sometimes with a shudder at truths, and subjects, to which Dickens would later return again and again. The real horrors of the Fleet Prison, which Pickwick and then Sam experience: ‘This is no fiction’, Dickens writes all too simply. Money, too, and class: the inequalities it fosters, as well as the opportunities for philanthropy, charity, generosity, it gives his heroes. The Pickwick Papers speculate to accumulate.

More often, though, and in miniature bite-size chunks, it is the relish with which he found a way of bringing to the page the ‘wery good taste’ of ‘Tongue’, and of making all his extraordinary range of characters, women as well as men, live so vividly.

These qualities brought readers together. At the height of Pickwick’s popularity sales reached 400,000 copies a month. And then, in the autumn of 1837, readers who had collected all 20 numbers – complete with the advertisements for household goods that had made the endpapers of each issue an early soap opera, and the illustrations that Hablot K Browne, or ‘Phiz’, had supplied to give another form of life to their adventures, perambulations and perils – took them to bookbinders, along with the title page, a preface and a list of errata supplied in the last double issue, and collected The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, by Charles Dickens. The English novel would never be the same again.

脚注

- The Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. by Madeline House, Graham Storey and Kathleen Tillotson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965- ), Vol. I, p. 129.

- His first name harking back to that cabman in Chapter 2, his surname to Dickens’s own childhood nurse, his whole name a rough redemption and extension of the wisdom of Samuel which his new employer, Samuel Pickwick, somehow continues to find the means to dispense, along with all the food and wine he can afford to consume.

撰稿人: Mark Wormald

Dr Mark Wormald is College Lecturer and Official Fellow in English at Pembroke College Cambridge. He edited The Pickwick Papers for Penguin Classics, and has published on a range of nineteenth and twentieth century writers, including Gerard Manley Hopkins, George Eliot, Salman Rushdie and Kazuo Ishiguro. He is the editor of the Ted Hughes Society Journal, and the co-editor with Terry Gifford and Neil Roberts of Ted Hughes: From Cambridge to Collected. His next book, The Catch: Fishing for Ted Hughes, will be published by Little Toller Books.