Theatre in the 19th century

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were only two main theatres in London. Emeritus Professor Jacky Bratton traces the development of theatre throughout the century, exploring the proliferation of venues, forms and writers.

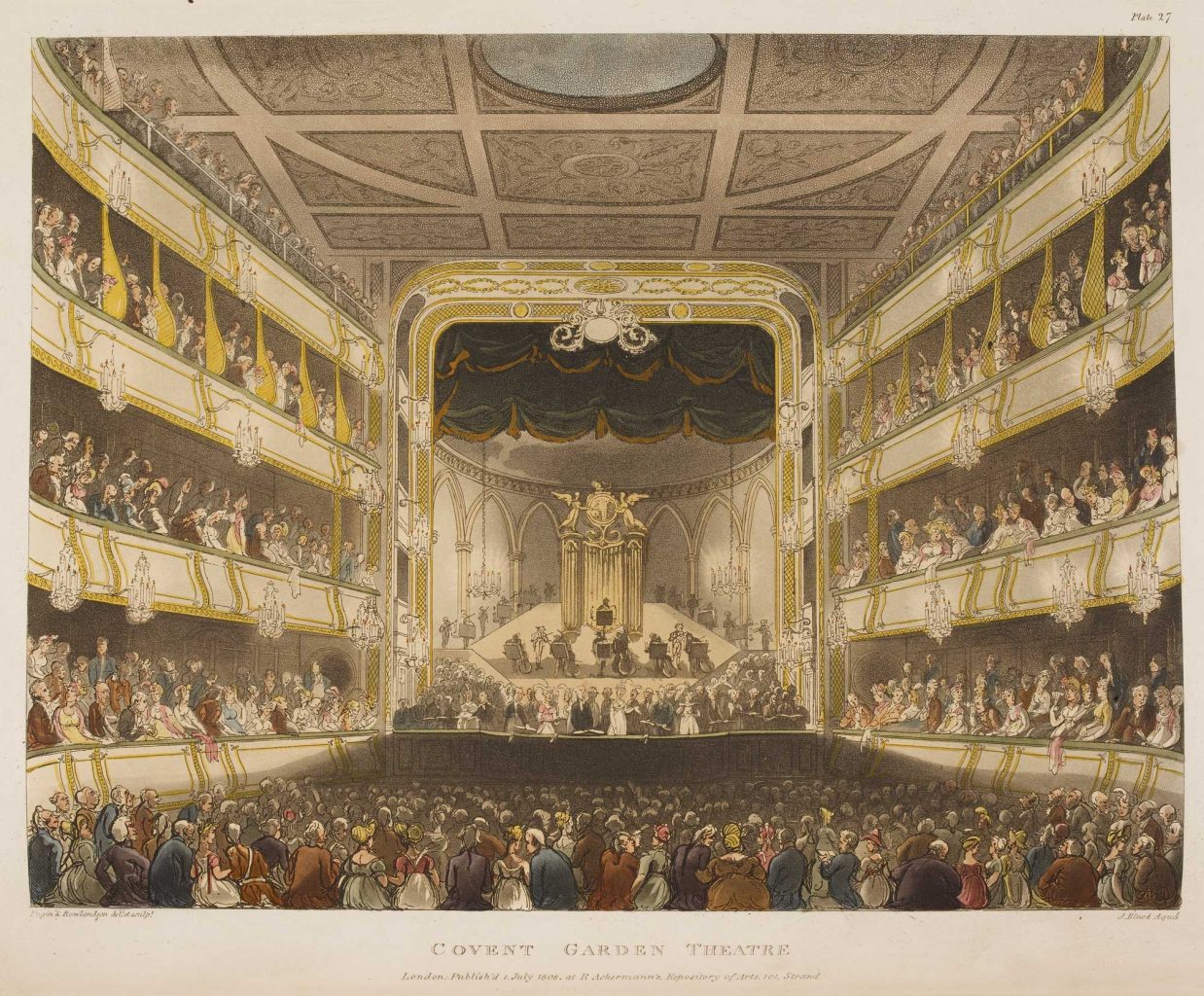

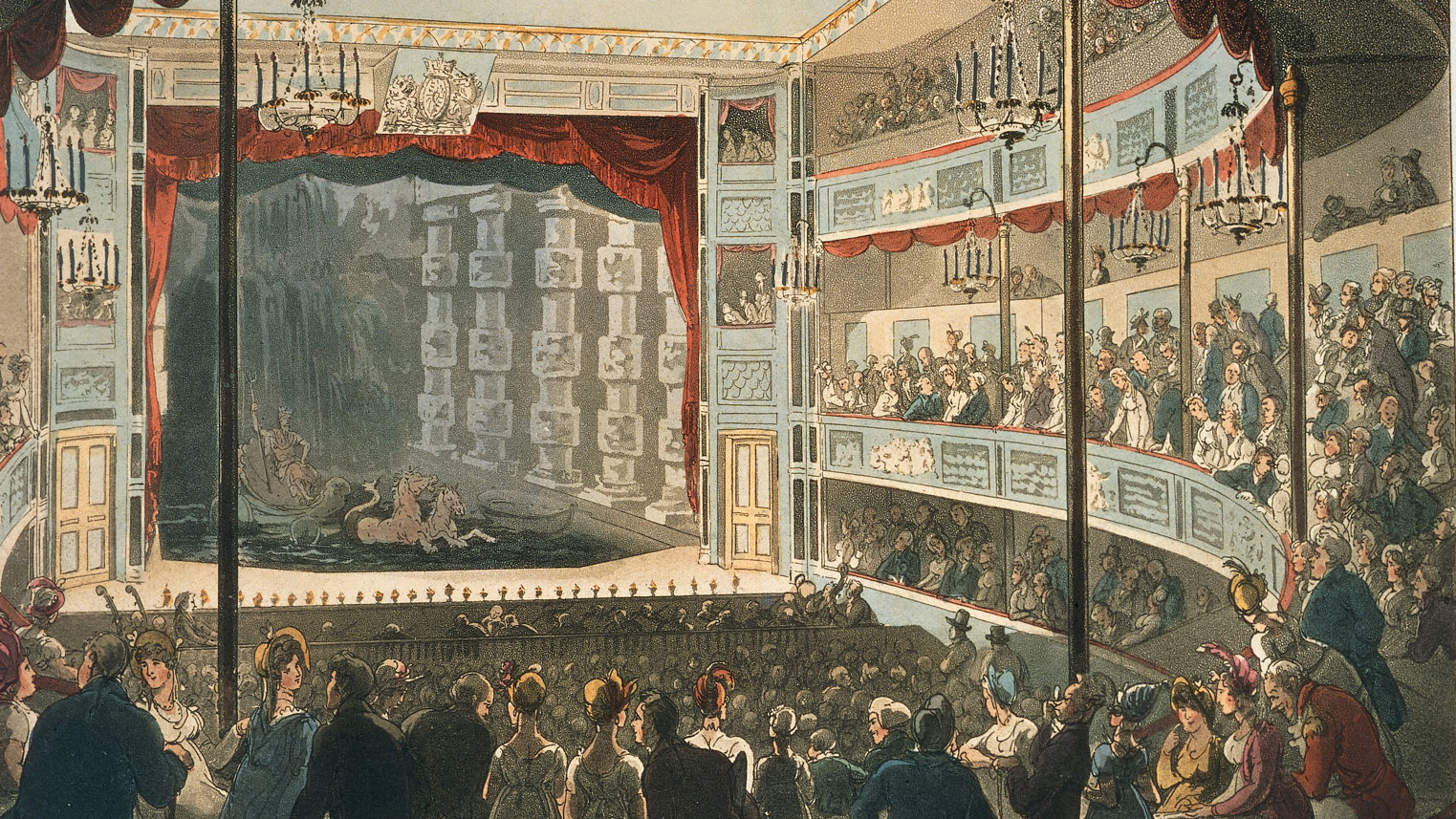

By 1800 there were not enough theatres in London for the explosively-growing population. The existing theatrical spaces, where the old civic community was arranged in box, pit and gallery, were under huge strain. The two winter theatres, Covent Garden and Drury Lane, had a dramatic duopoly granted in the 17th century, meaning theirs were the only managements officially allowed to put on plays in London during the winter season. They had developed over the years into large, often rowdy meeting places for all kinds of purposes. They did put on serious drama, but also anything that would please a large crowd, including lion taming in a cage and battles on horseback. There were two royal boxes, a huge gallery, and on the ground floor the pit, where people came and went, leaping over the backless benches, calling to their friends up in the boxes. In the lobbies and saloons, men could expect to meet prostitutes, who got in at special prices with a season ticket to do business there. Consequently, the theatres (which were also prone to catching fire) had been repeatedly rebuilt and enlarged, until in 1809 manager John Philip Kemble opened a colossal new Covent Garden financed by adding a tier of private boxes, for rich subscribers, and increasing prices elsewhere. His apparent privatisation of what the public regarded as a national meeting place was met with howls of rebellion: the ‘Old Price riots’ that lasted for more than 60 nights, during which an improvised performance in the auditorium, complete with dancing, singing, trumpets and drums, drowned out his Macbeth. In the end, he had to capitulate.

Expansion

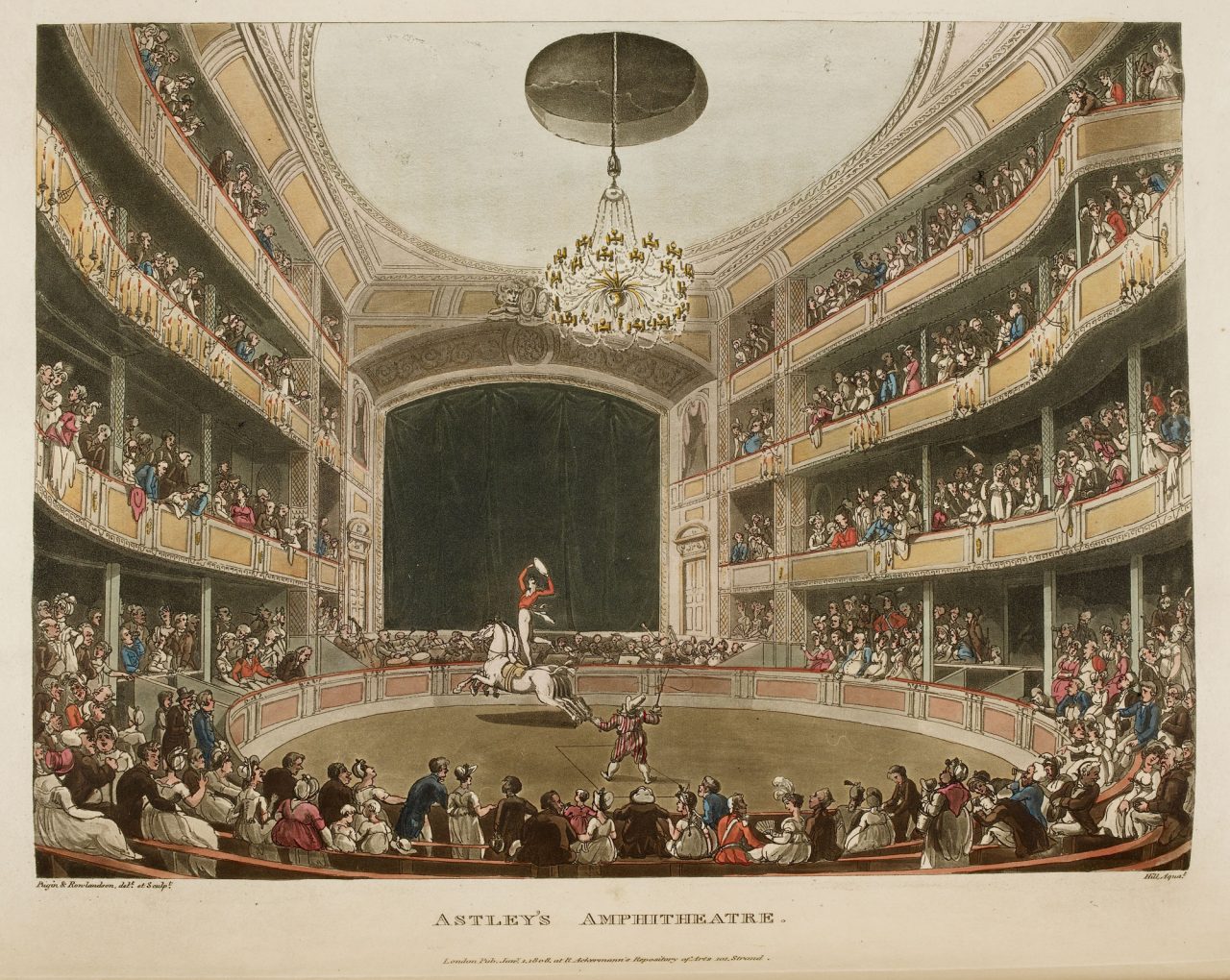

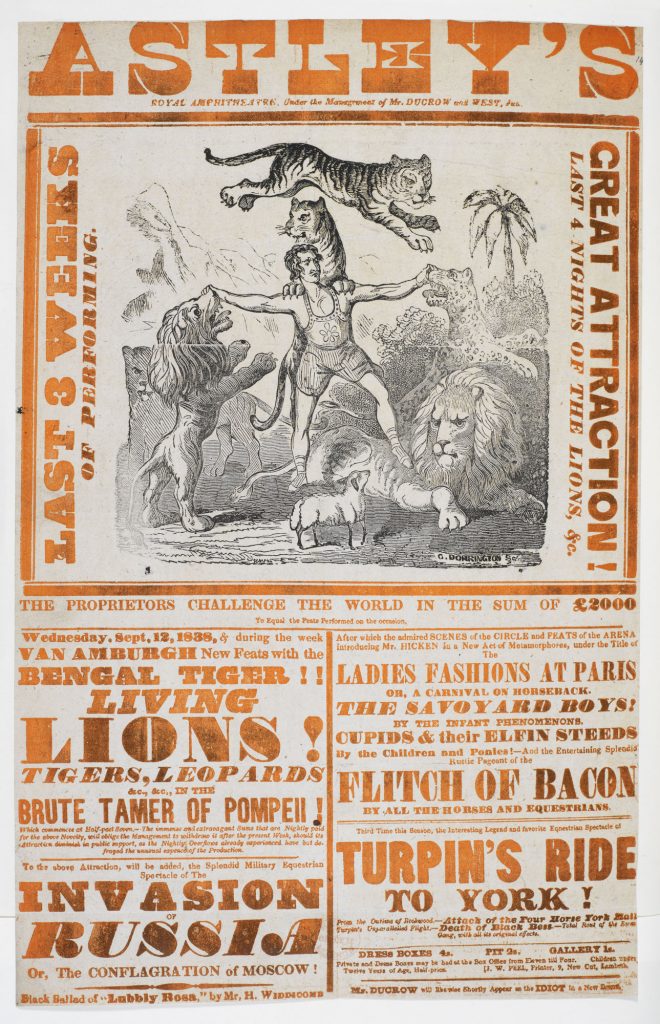

But theatre confined to two massive buildings, with only the smaller Haymarket in the summer, was no longer enough for the world’s largest city. In the early years of the century the modern West End began to emerge when the authorities (the Lord Chamberlain’s office) partially broke the duopoly by allowing a few ‘burletta’ licences – permission to do plays with music – to small theatres along the Strand, like Jane Scott’s Sans Pareil (later to become the Adelphi). Other entrepreneurs began to operate outside the metropolitan rules, relying on magistrate’s licences. This was allowed beyond London, where theatres normally opened for short seasons by local permission. Around London theatres licensed in this way, such as the South Bank venues, Astley’s Amphitheatre – where the first circus ring in the world was combined with a stage for the better presentation of wars and sieges – and the Coburg, today’s Old Vic, were regularly warned off or prosecuted when they ventured too far. Lesser places were summarily closed.

Ingenuity and inventiveness

The very restrictions that forbade the new theatres to do Shakespeare or other straight plays perhaps partly inspired the brilliant ingenuity and inventiveness of entertainment at this time. Unlicensed premises relied on silent or musically-accompanied action, physical theatre, animals and acrobatics, and thus both melodrama and the Victorian pantomime were developed. Without poetry and declamation, much more was needed from scenery and visual effects, and these were also essential in the major theatres, because lighting and auditorium design, making it easy to see and hear the players, did not keep up with the increasing size of theatres. And audiences, in the first half of the century, were not passive or still: the auditorium was as well-lit as the stage, a place of social meeting and greeting, coming and going; the night was long – up to five hours, with several different pieces on offer – and an extra influx of people who had already been enjoying a night out arrived at about nine, getting in at half price, and needing to be instantly involved in the event. Therefore a more spectacular, visual style took over from the static 18th-century emphasis on the spoken word. Individual actors developed a style that combined gesture, movement and speech, as well as accompanying music and often song, to make their points on a large and visually exciting stage. The new celebrities, from Sarah Siddons, Edmund Kean and T P Cooke(the first Frankenstein’s monster) at the beginning of the century to Henry Irving at the end, were known for their thrilling ability to command attention to their slightest move, by gaslight, wordlessly, and over the heads of 3,000 people.

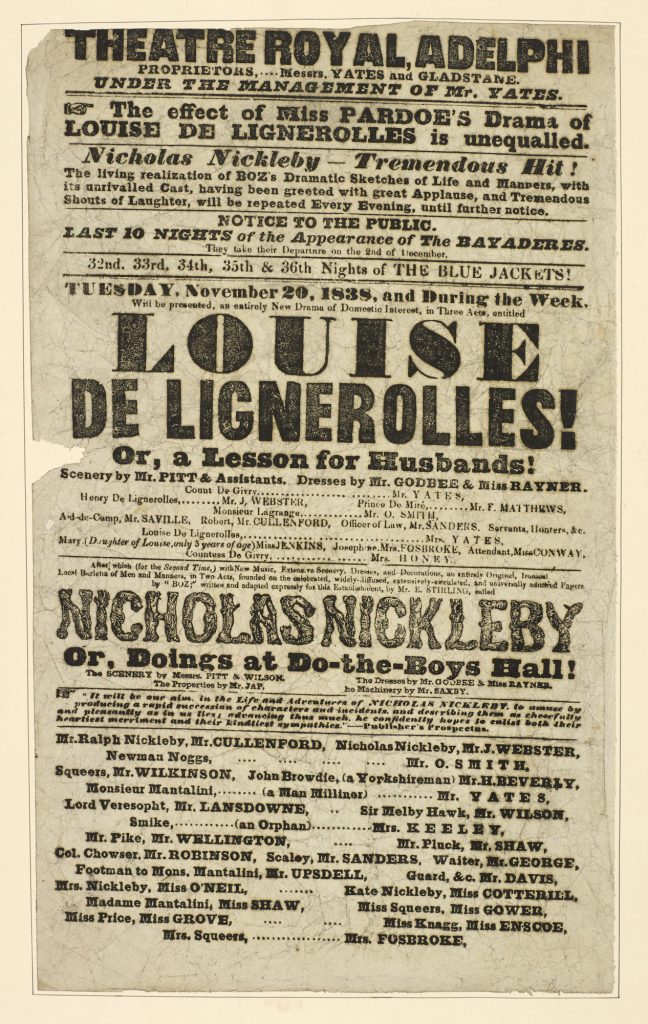

In 1843, propelled by the Victorian urge to control and educate the new urban masses, Parliament finally changed the licensing laws and permitted all theatres to stage straight plays, hoping both to civilise the audiences and to encourage more literate modern playwriting to develop. The unexpected consequence was not more productions of Shakespeare, inspiring new Bards, but the growth of the West End, and the burgeoning of theatres and other, unpredicted forms of entertainment. Freed from restriction, the music hall and many other shows that were not strictly dramatic developed, to serve a large but divided audience with many different tastes and capacities to spend. The two old London playhouses, similarly dividing between high-brow and mass offerings, became venues for two kinds of musical theatre: the opera at Covent Garden, and a spectacular annual pantomime at Drury Lane alternating with sensational melodramas, reliant on stunts like a working paddle steamer or real horses racing on stage – not so far from the breathtaking ‘real’ scene-dressing deployed there today. As Victorian technology – electric lighting and hydraulics – advanced, the scale and excitement of the on-stage battles, storms, explosions and transformations grew, until they slid seamlessly, at the turn of the 20th century, into the new medium of film.

Literary dramatists

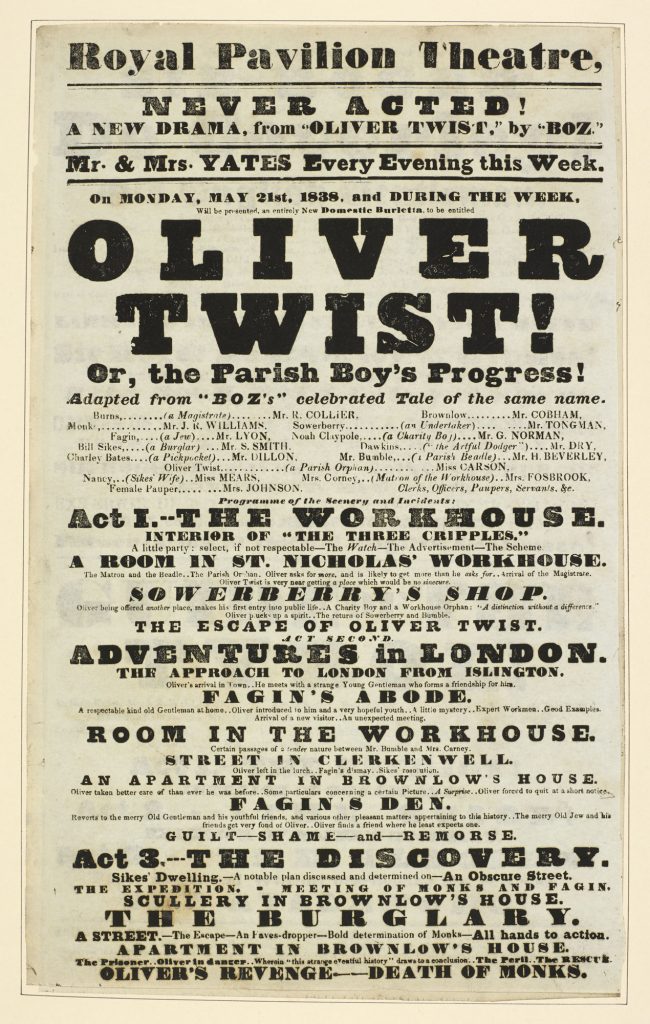

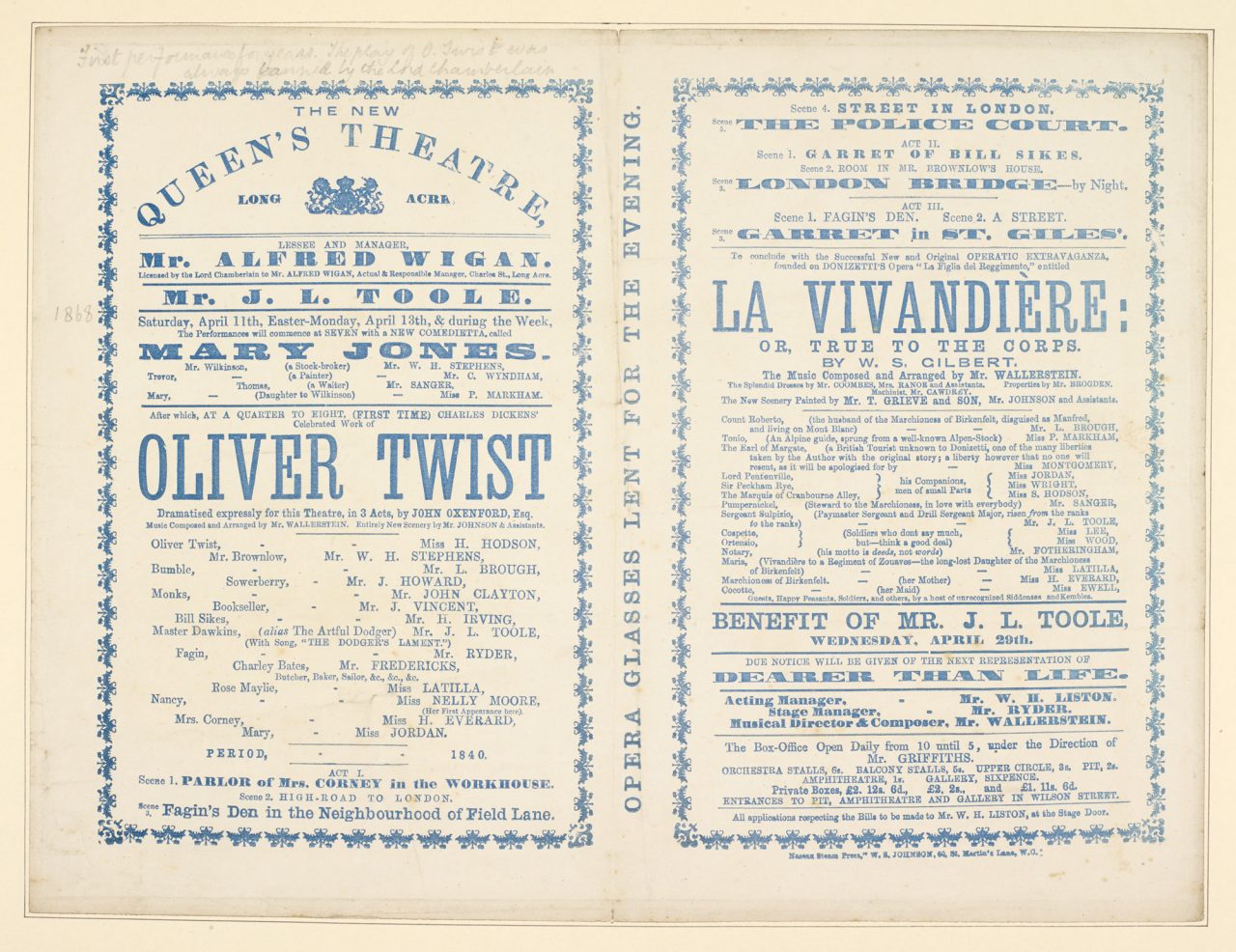

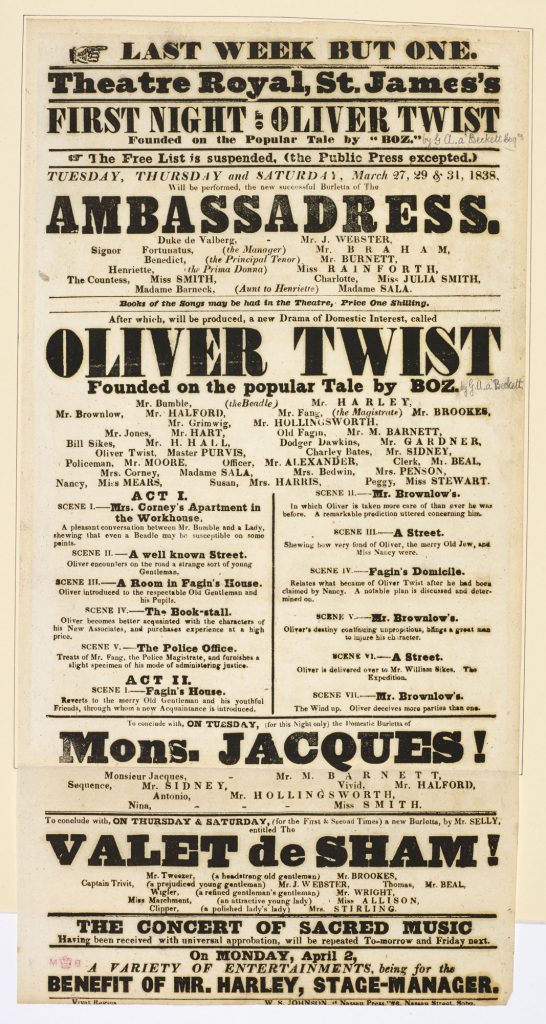

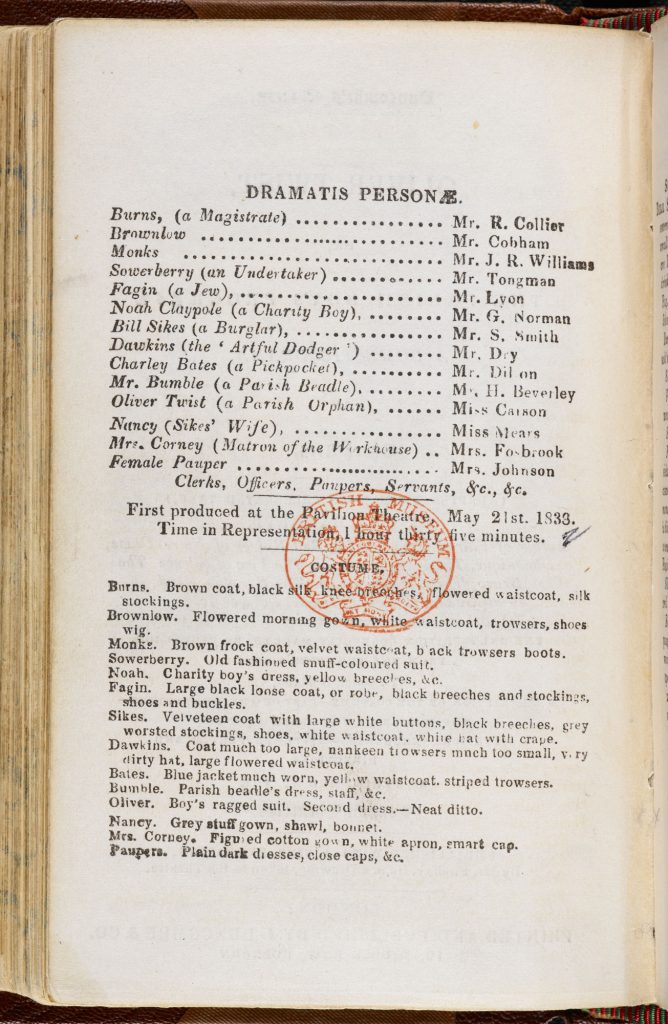

Meanwhile the hoped-for new literary dramatists did not emerge very quickly; and this was partly due to the mistaken faith in Shakespeare, which led to numerous attempts to write five-act plays in verse on historical or mythological subjects, even though no one really wanted to see them. Consequently the writers who produced scripts about the modern world – comic, burlesque, farcical and thrilling pieces which were used by the new theatres – were not seen as real artists, and were badly paid as well as socially despised. Charles Dickens, who had a deep love of theatre and might have developed into the 19th-century’s classic dramatist, therefore steered clear of stage writing himself and made his fortune in the novel. The theatres, however, knew better, and dramatised his work hot off the press, so that there could be 10 versions of one of his stories playing even before he had finished writing the monthly parts of the novel. Eventually, he made a truce with the West End over his Christmas books, arranging that they would appear on Christmas Eve, simultaneously in print and also on the stage of the Adelphi or the Lyceum, where he had provided the pre-publication text to a dramaturg and worked with the company in rehearsals. It is arguable that Dickens’s novels have always been so well known and loved partly because they exist in this unique symbiosis with performance, and so can be made anew for each generation of viewers as well as still read in the original form.

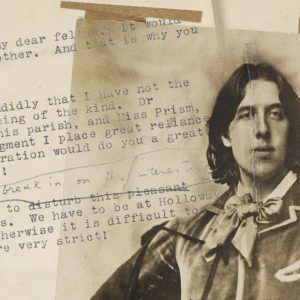

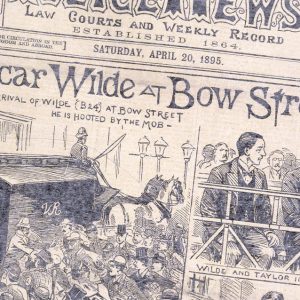

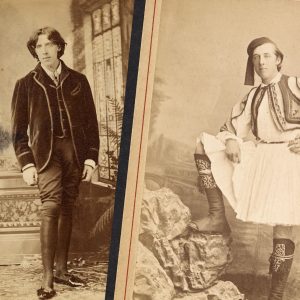

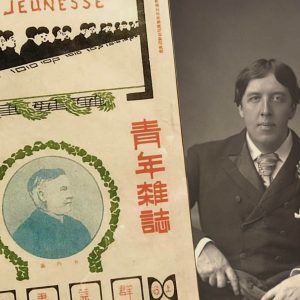

Legislation slowly caught up with its failure to inspire writers to work for the stage, and eventually the copyright laws began to encourage them. By the 1870s and 80s musical theatre creators like Gilbert and Sullivan could make a good living, and a generation of writers like Henry Arthur Jones, Arthur Wing Pinero and Oscar Wilde made their names working in and beyond the forms developed by the now-forgotten earlier melodramatists like Douglas Jerrold and Tom Taylor. But at the end of the century a new critical generation, headed by the radical actress-manager Janet Achurch and critics William Archer and George Bernard Shaw, looked to a different artistic understanding of the world, and championed the importation of the plays of Ibsen, Zola and eventually also Strindberg and Chekhov. This was a new ideology, a new way of seeing: Realism, Naturalism and Modernism supersede and indeed reject the melodramatic and comic world-view of the 19th-century stage. But despite those writers’ propaganda against it, that view did not die, and its further evolution in much 20th- and 21st-century ‘popular’ entertainment, in television and film, is now being recognised. That understanding should lead us to a better appreciation of its vivid, moving and supremely entertaining manifestation on the Victorian stage.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Jacky Bratton

Jacky Bratton is emeritus professor of theatre and cultural history at Royal Holloway University of London. Her research ranges widely over the long 19th century, from children’s books to clowns, and includes an interest in the roots of the popular song and in melodrama. Her most recent book is The Making of the West End Stage: marriage, management and the mapping of gender in London, 1830-1870 (Cambridge University Press 2011).