Penny dreadfuls

The penny dreadful was a 19th-century publishing phenomenon. Judith Flanders explains what made these cheap, sensational, highly illustrated stories so popular with the Victorian public.

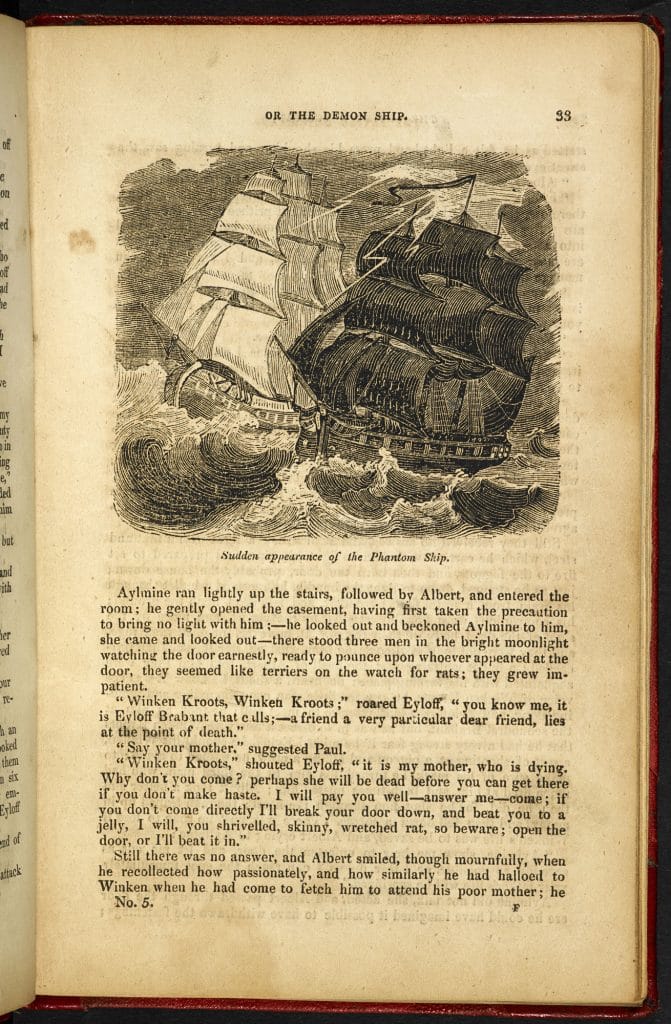

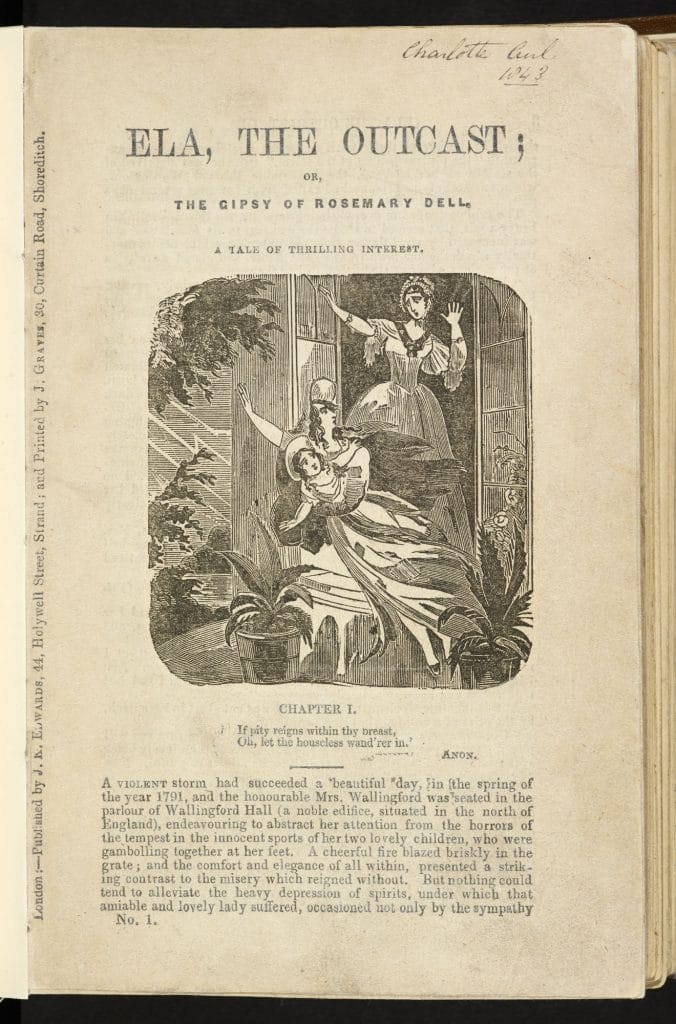

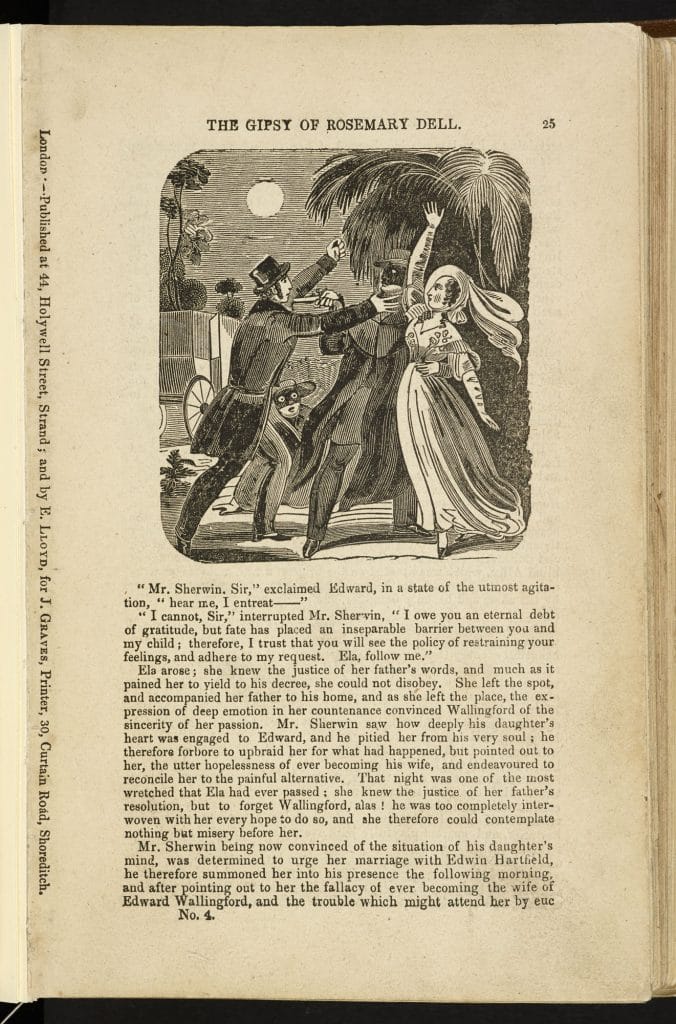

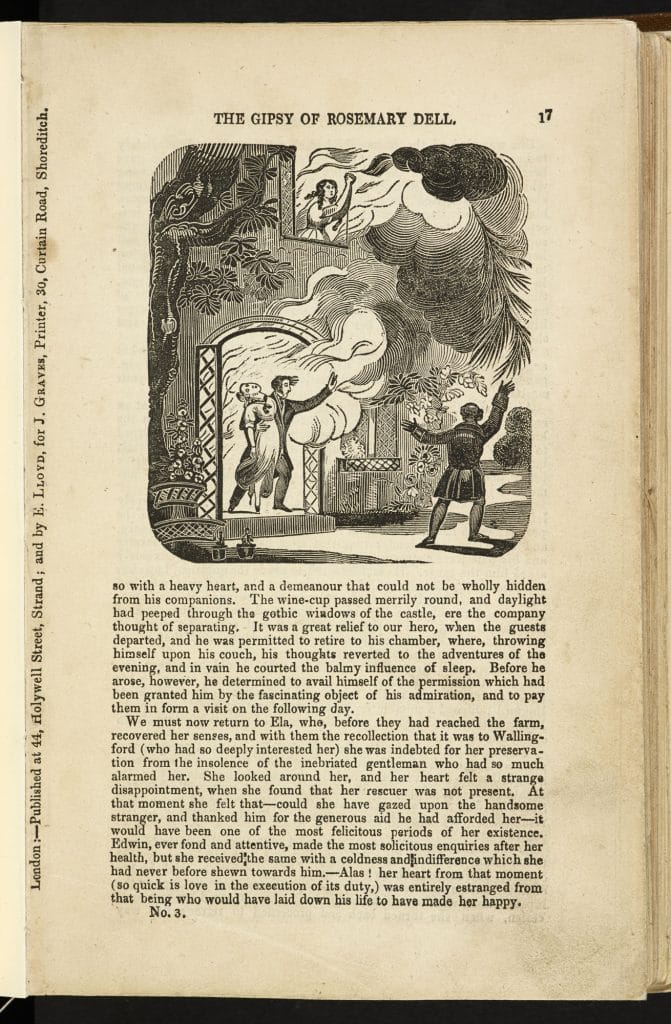

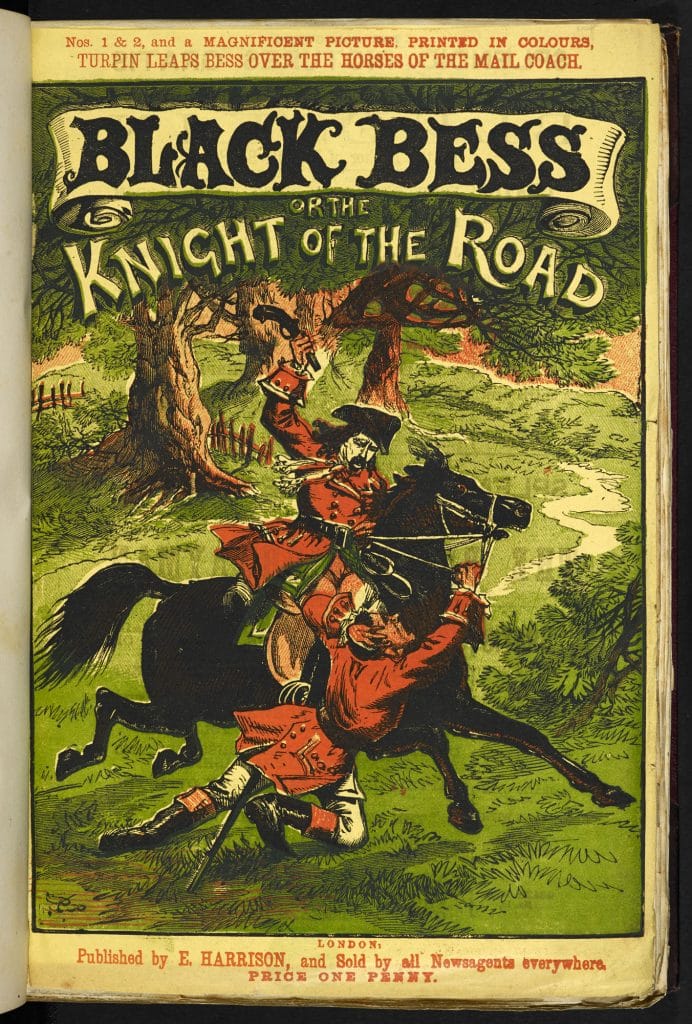

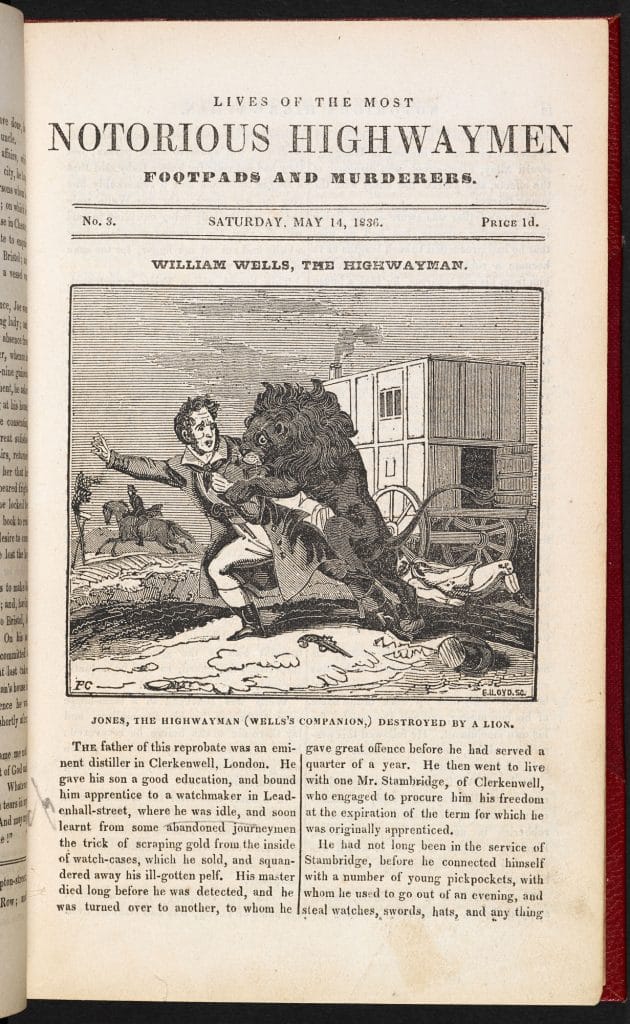

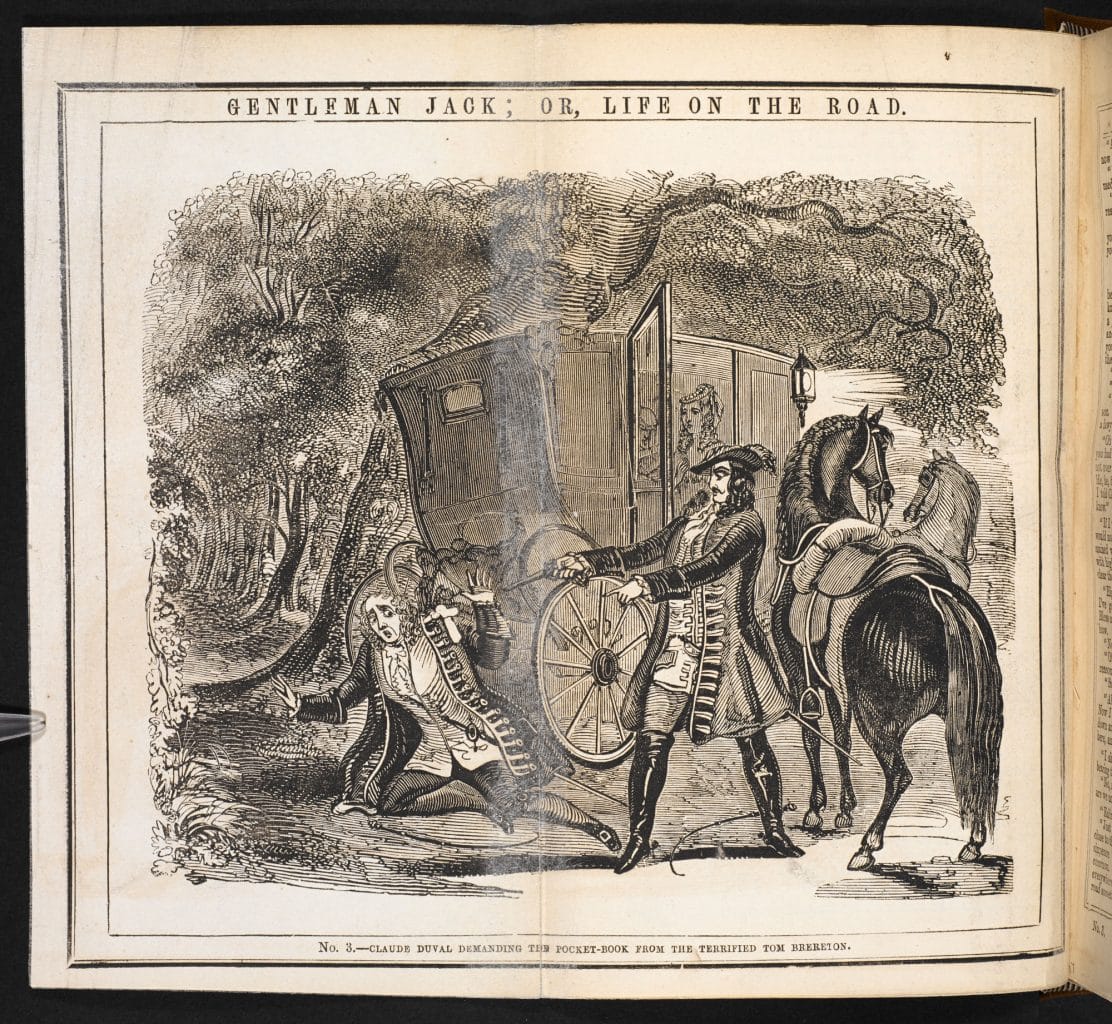

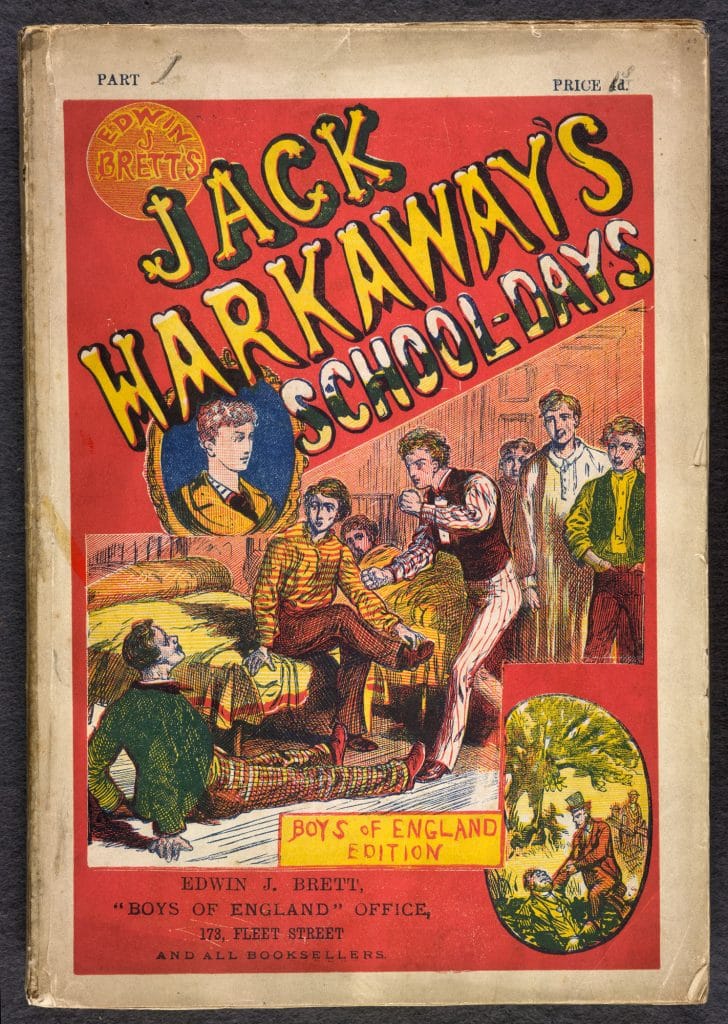

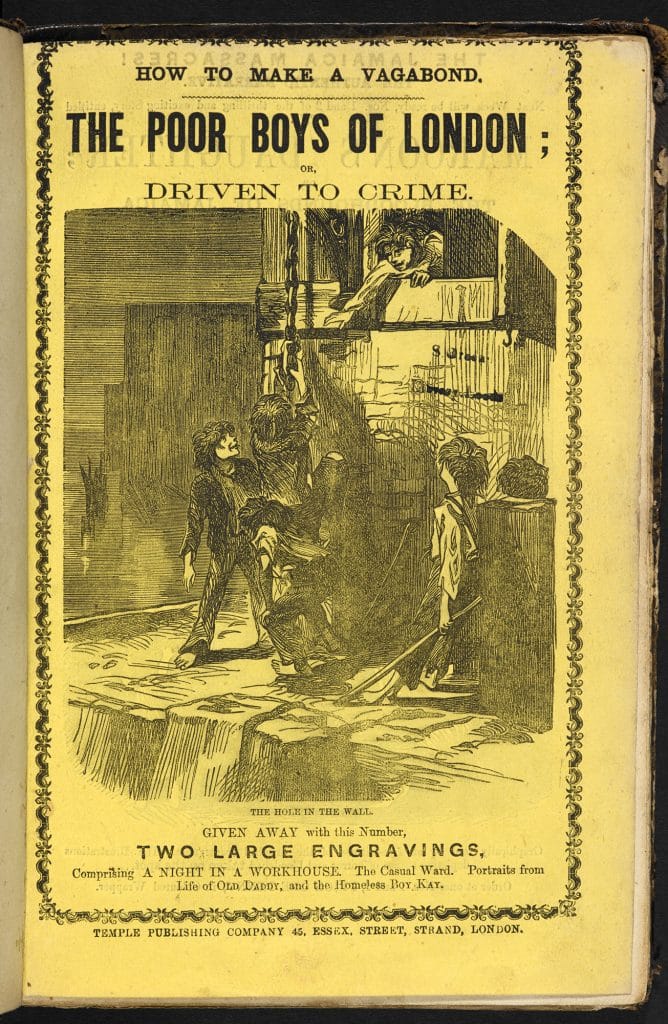

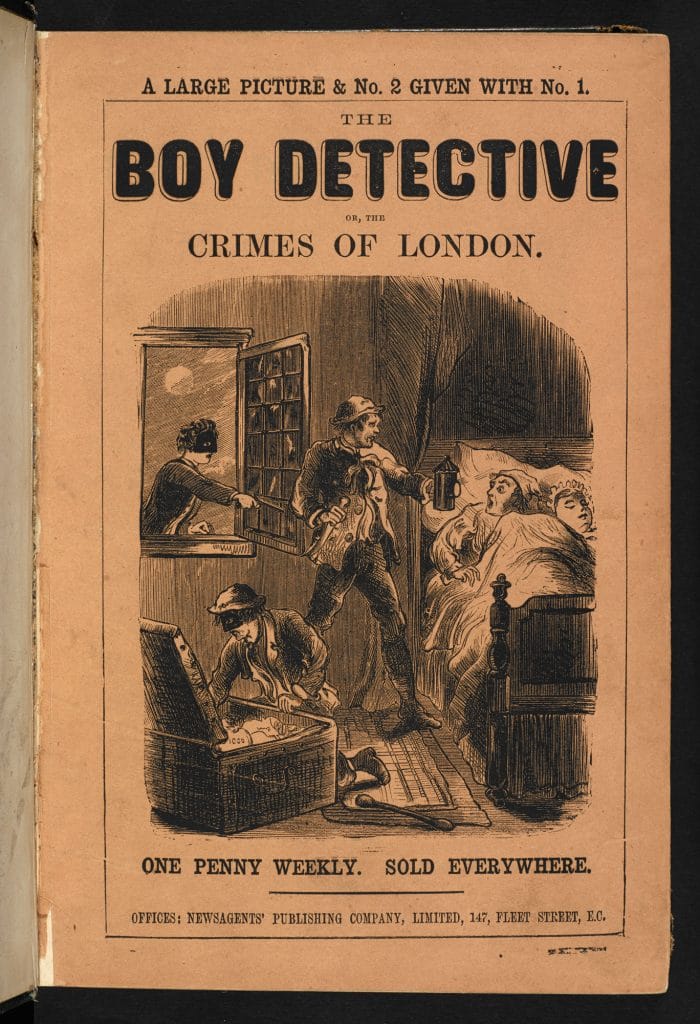

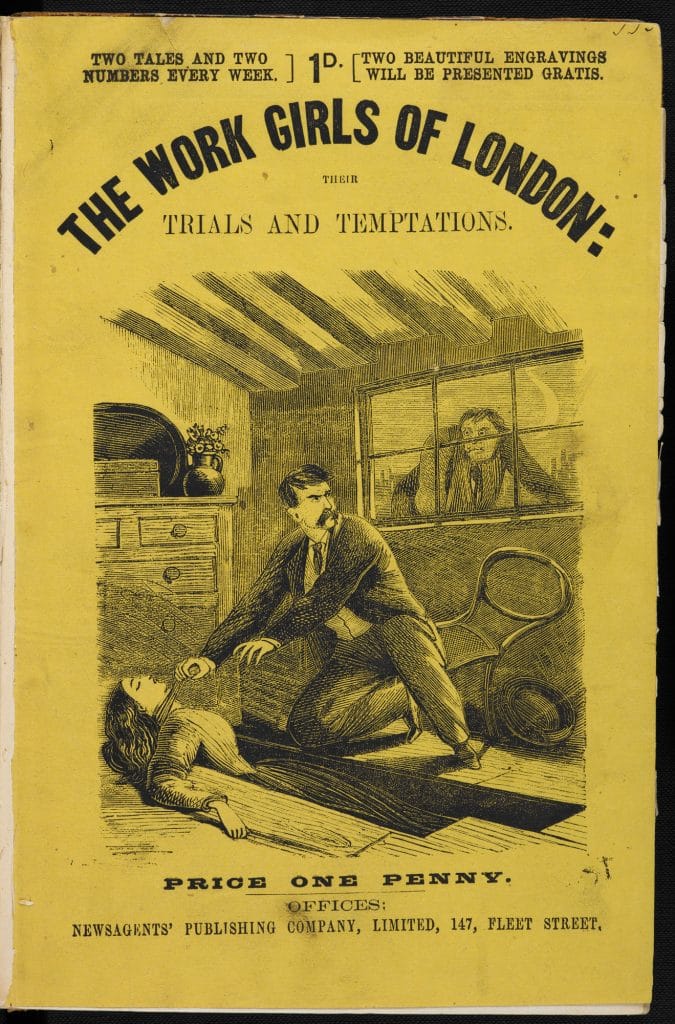

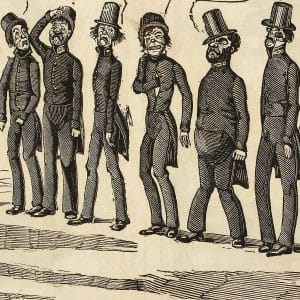

In the 1830s, increasing literacy and improving technology saw a boom in cheap fiction for the working classes. ‘Penny bloods’ was the original name for the booklets that, in the 1860s, were renamed penny dreadfuls and told stories of adventure, initially of pirates and highwaymen, later concentrating on crime and detection. Issued weekly, each ‘number’, or episode, was eight (occasionally 16) pages, with a black-and-white illustration on the top half of the front page. Double columns of text filled the rest, breaking off at the bottom of the final page, even if it was the middle of a sentence.

The success of highwaymen and gothic tales

The bloods were astonishingly successful, creating a vast new readership. Between 1830 and 1850 there were up to 100 publishers of penny-fiction, as well as the many magazines which now wholeheartedly embraced the genre. At first the bloods copied popular cheap fiction’s love of late 18th-century gothic tales, the more sensational the better, ‘a world,’ said one writer, ‘of dormant peerages, of murderous baronets, and ladies of title addicted to the study of toxicology [the study of poison], of gipsies and brigand-chiefs, men with masks and women with daggers, of stolen children, withered hags, heartless gamesters, nefarious roués, foreign princesses’.[1]

The first ever penny-blood, in 1836, was Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, &c., in 60 numbers. Highwaymen remained a favourite. Gentleman Jack was published over four years, without too much worry for historical accuracy or continuity. (One character was, rather carelessly, killed twice.) Dick Turpin was a great favourite. His story, and especially the time he (supposedly) rode the 200 miles from London to York overnight, was retold endlessly. In Black Bess; or, The Knight of the Road, Turpin was not executed until page 2,207.

The illustrations were an essential element, as much an advertising tool as art. One regular reader said, ‘You see’s an engraving of a man hung up, burning over a fire, and some…go mad if they couldn’t learn what he’d been doing, who he was, and all about him.’ It is not surprising, therefore, that one publisher’s standing instruction to his illustrators was, ‘more blood – much more blood!’

Slums, true crime and detectives

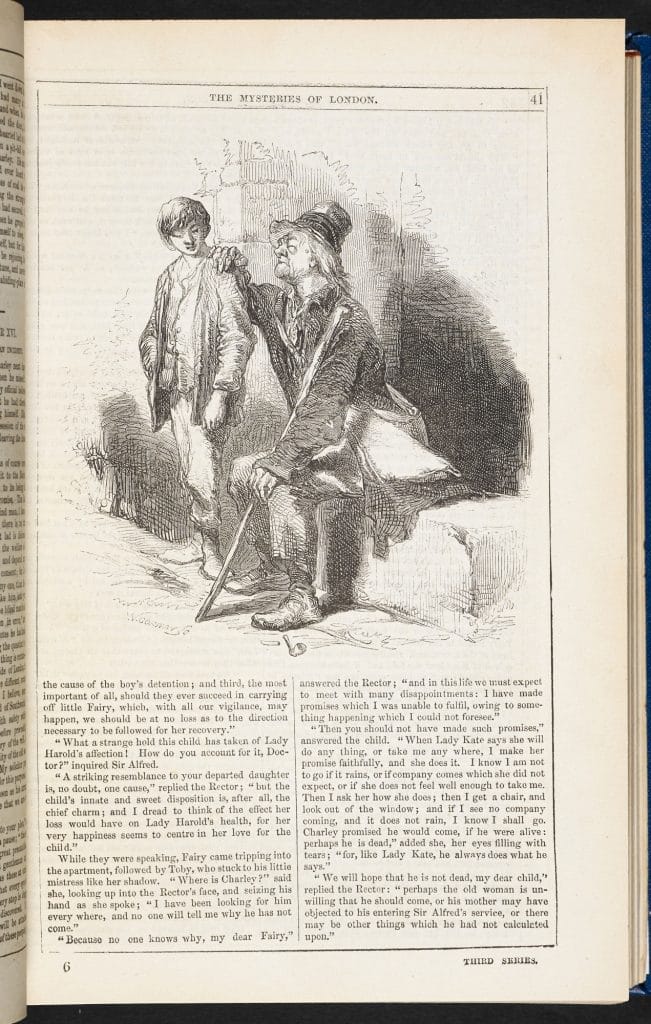

The most successful penny-blood, and what might possibly be the most successful series the world has ever seen, Mysteries of London, first appeared in 1844, written by G W M Reynolds. He based it on a French book, but it soon took on a life of its own, spanning 12 years, 624 numbers and nearly 4.5 million words . Instead of highwaymen, this series was much closer its readers’ own lives, contrasting the dreadful world of the slums with the decadent life of the careless rich.

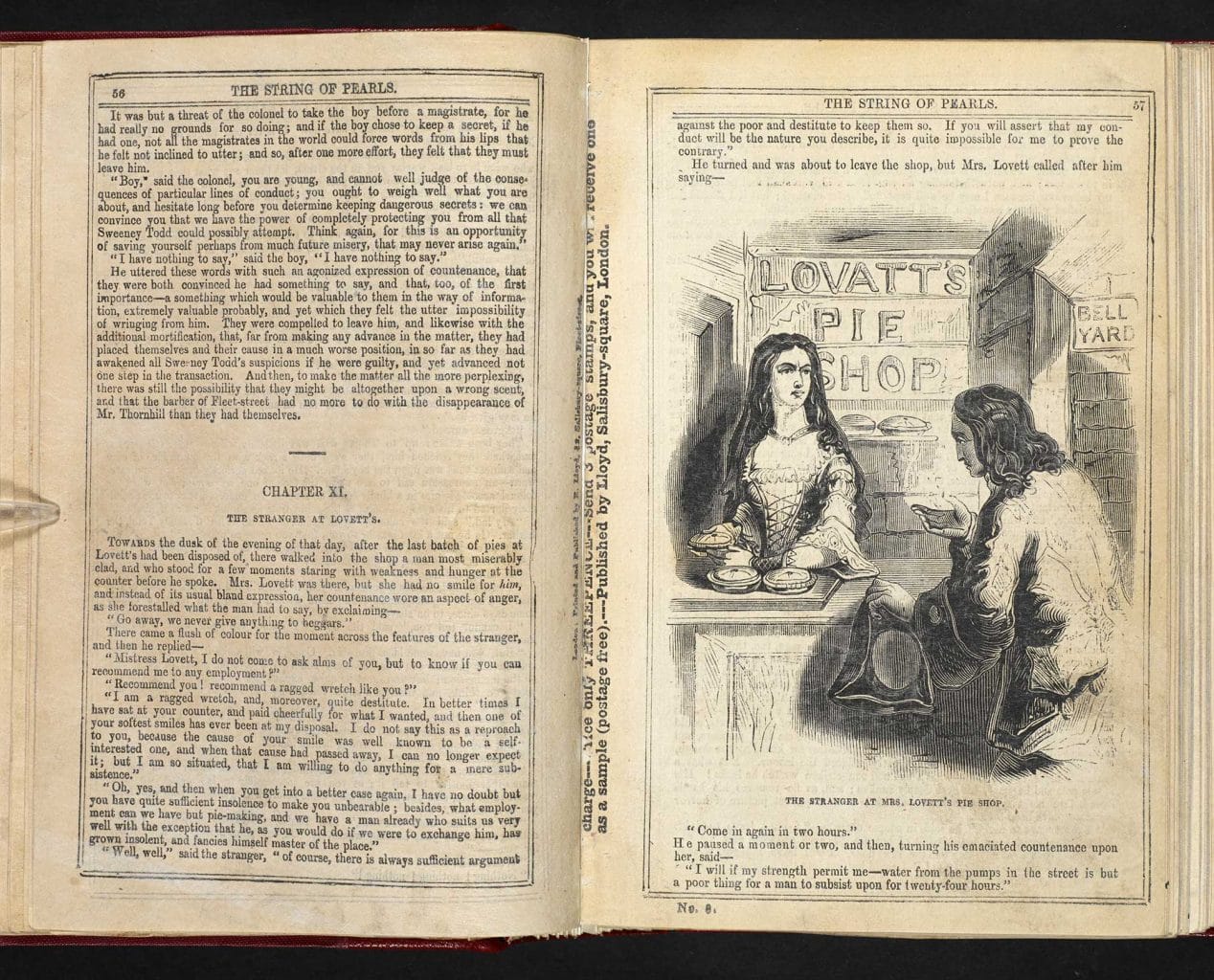

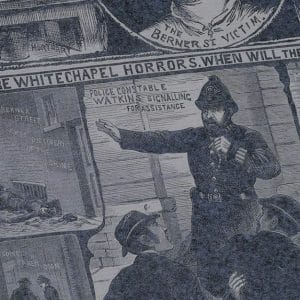

Later, after highwaymen and then evil aristocrats fell out of fashion, penny-bloods found even more success with stories of true crimes, especially murders. And if there were no good real-life crimes current, then the bloods invented them. The most successful of them was the story of Sweeney Todd. The ‘Demon Barber’ first appeared in a blood entitled The String of Pearls, which began publication in 1846. Even before it reached its conclusion, it was adapted for the stage, setting the murderous barber, who killed his clients for his neighbour Mrs Lovett to bake into meat-pies, on the road to world fame.

Soon, however, it was the pursuers, not the murderers, who took centre-stage. In 1865, a 70-part penny dreadful, The Boy Detective, or, The Crimes of London, appeared, with its hero, Ernest Keen, who runs away from home and works for a police inspector, ‘so cleverly that the fly coves called him the BOY DETECTIVE!’

Penny-bloods had originally had a broad readership, but in the 1860s the focus narrowed, and children became the main target. There were dozens of titles – The Wild Boys of London(1864–66), The Poor Boys of London (c.1866), even The Work Girls of London (1865).

The beginning of authors’ careers and a new genre

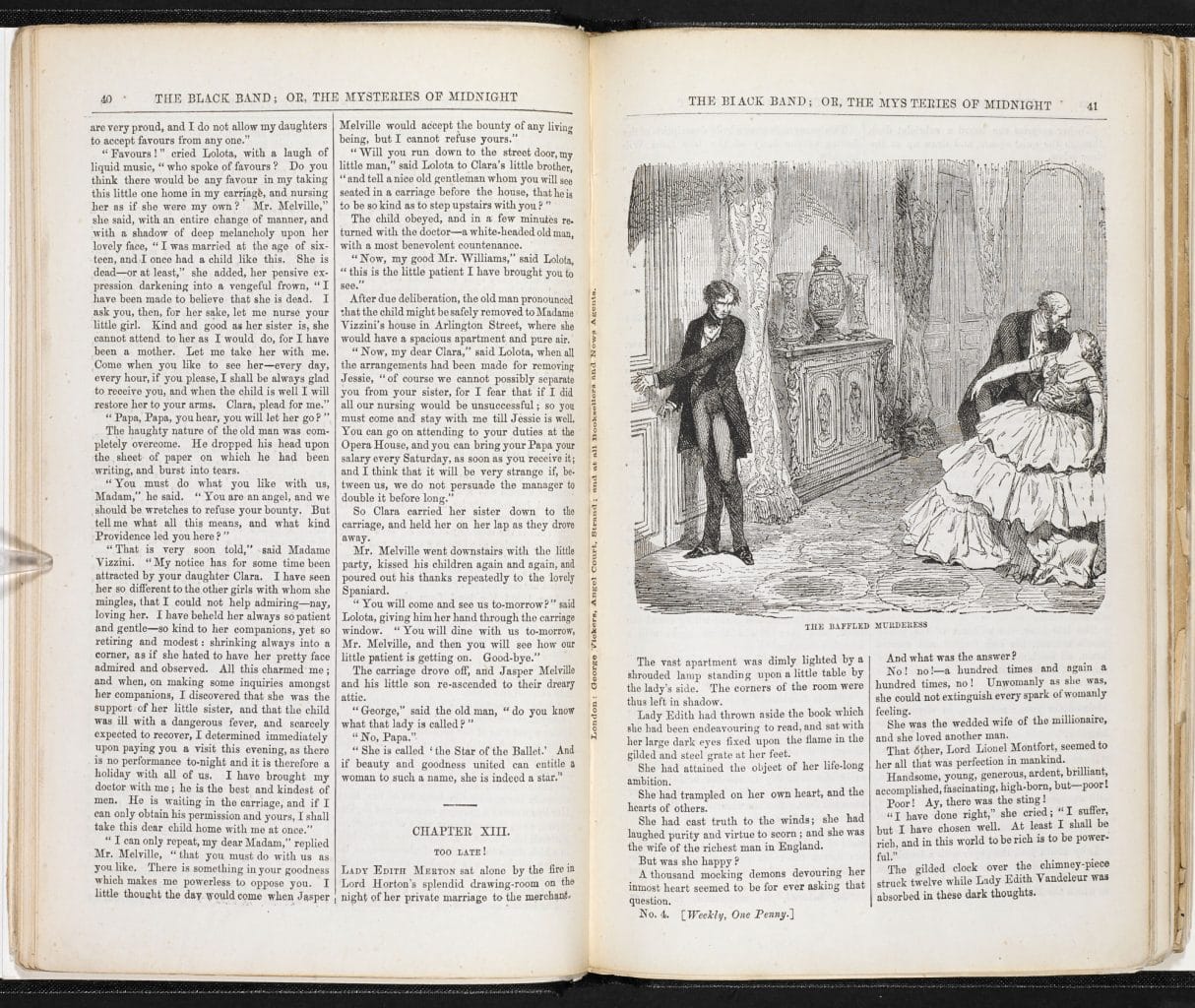

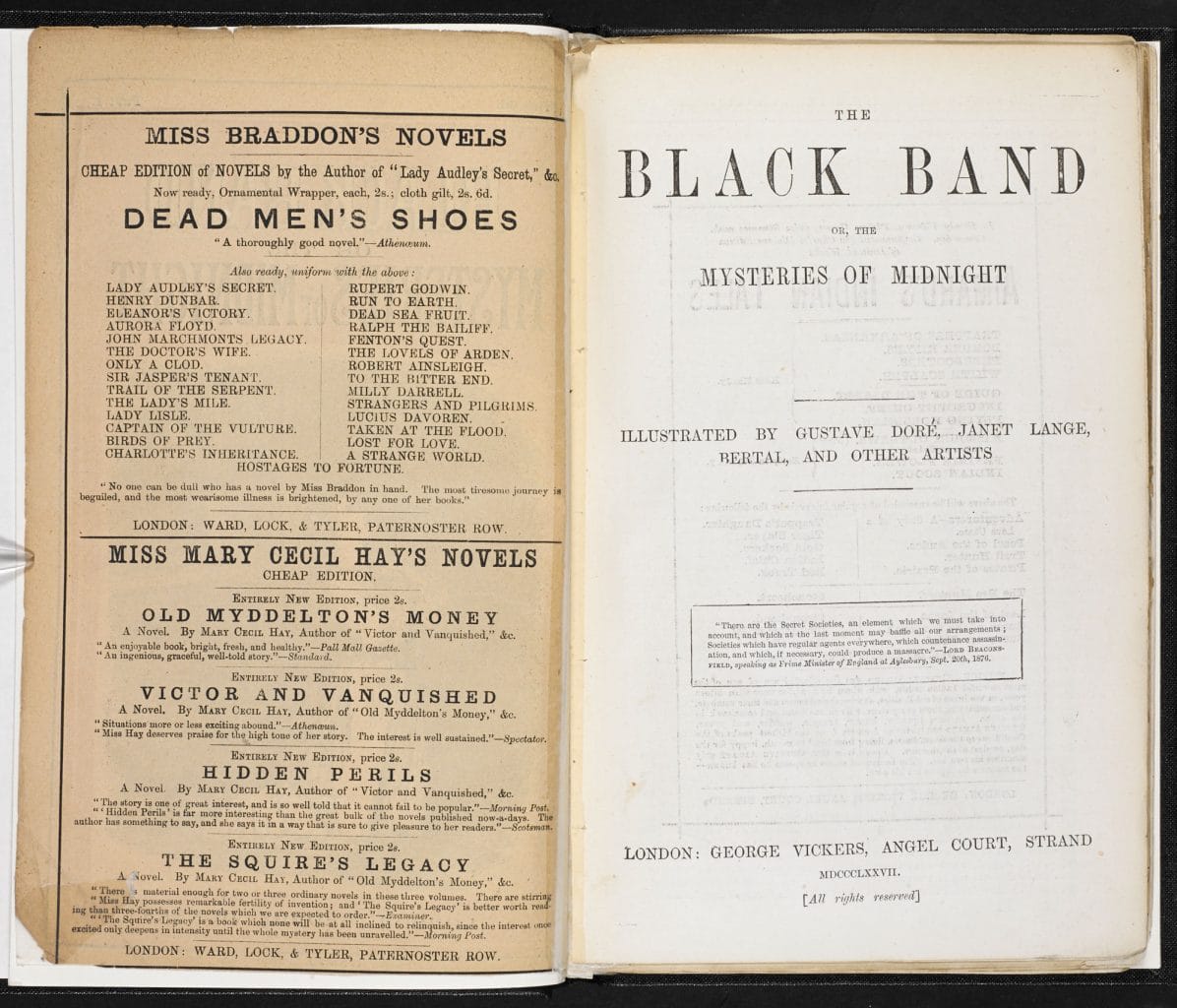

Several authors who later published more respectable popular fiction began their careers in penny-bloods, including the journalist G. A. Sala, a protégé of Dickens, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, later the author of the bestselling Lady Audley’s Secret, who began as the (pseudonymous) author of The Black Band, or, The Mysteries of Midnight, complete with lady-murderess who organises a European-wide network of criminals.

As Mrs Braddon herself said, ‘the amount of crime, treachery, murder and slow poisoning, & general infamy required [by my readers]…is something terrible’. Yet it was precisely these ingredients that led the way to the ‘sensation’ novel. Mrs Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, or Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White picked up on the high melodrama of the penny dreadful scenarios, but instead of highwaymen, or pirates, or gothic dungeons, tucked them all neatly away under a tidy domestic façade that reflected those of its middle-class readers, creating a new genre out of an old form.

The text in the article is © Judith Flanders. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders is a historian and author who focusses on the Victorian period. Her most recent book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London was published in 2012.