Oscar Wilde: Curator’s pick

In this article, Alexandra Ault explores some of the original manuscripts created by Oscar Wilde, which bring us closer to his writing life.

Oscar Wilde is many things to many people. To me, Wilde was brilliant at exploring nuanced social spaces, many of which are as vivid and real to us now as they were to audiences in the late 19th century. Wilde’s manuscripts allow us to examine his writing processes and to investigate some of the social, literary, theatrical and geographical spaces his work inhabited. The British Library houses some of the most important original manuscripts by Oscar Wilde as well as rich collections relating to his life.

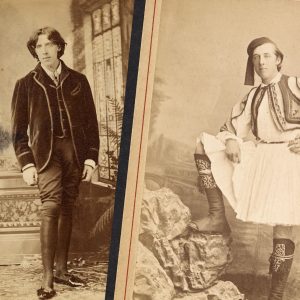

We have recently fully digitised our holdings of all of the play scripts and drafts for Wilde’s four key plays. In this short essay, I choose manuscripts, drafts and photographs that open up moments in Wilde’s writing life: from deleted scenes to staged photographs; from instructions for a typist to opinions on Shakespeare, Wilde’s words reach into so many arenas.

What is the curator’s favourite Wilde collection item?

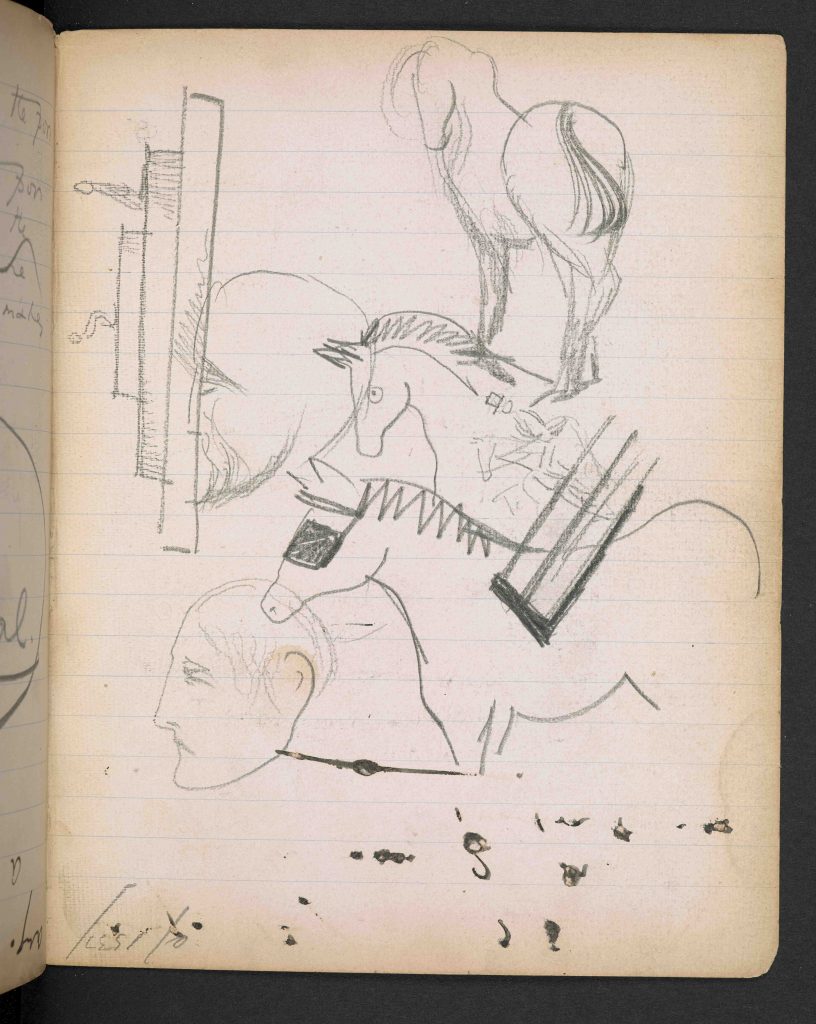

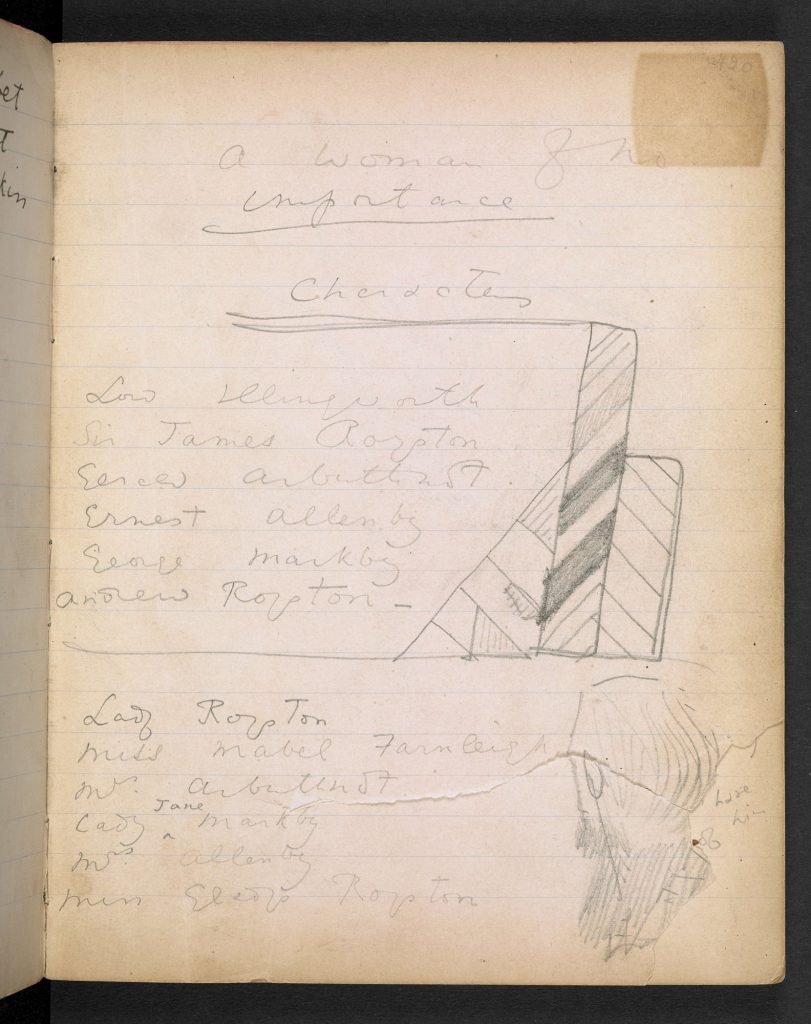

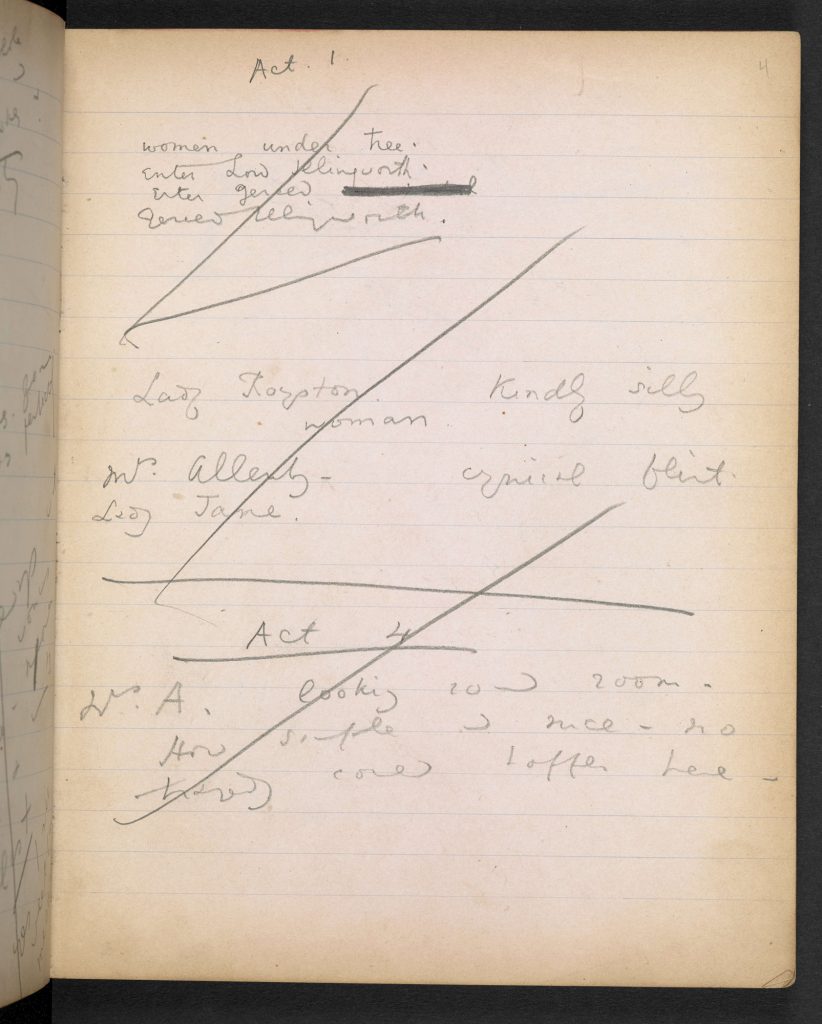

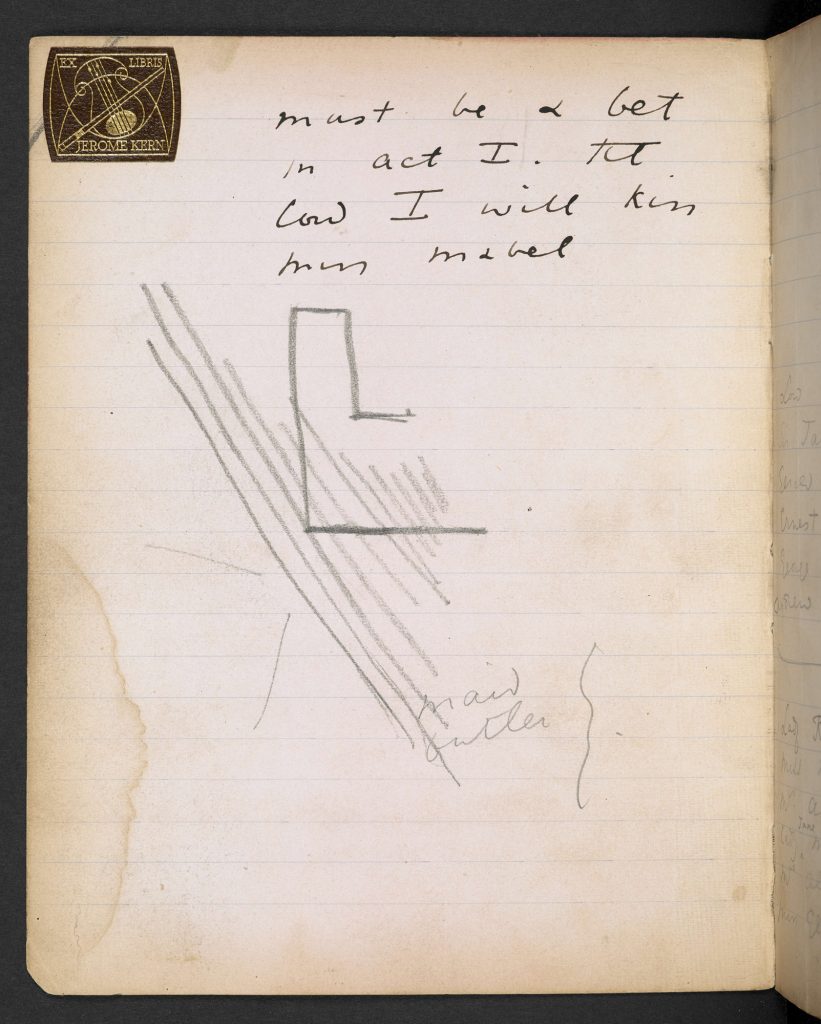

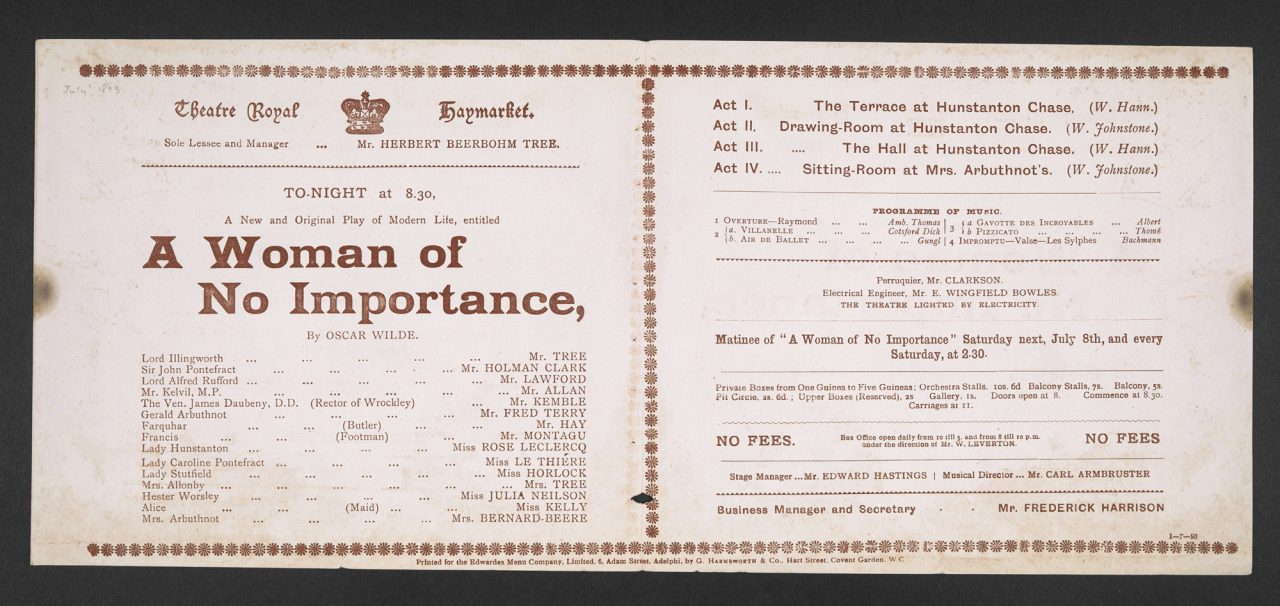

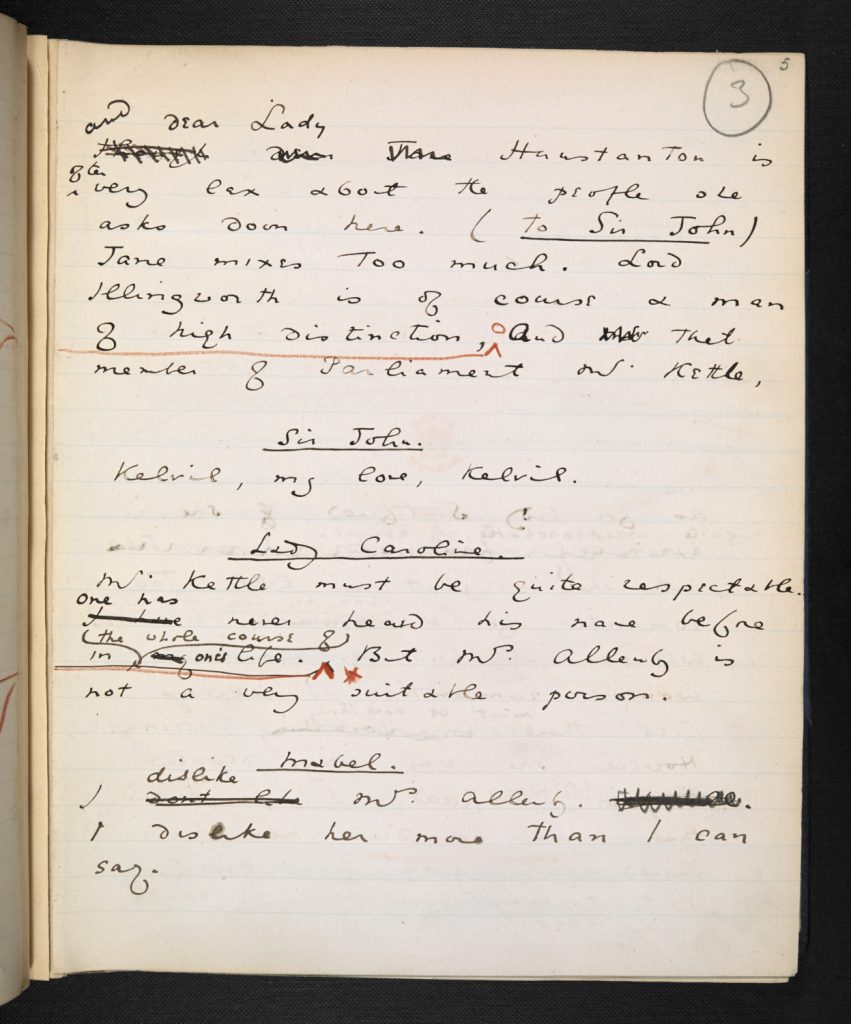

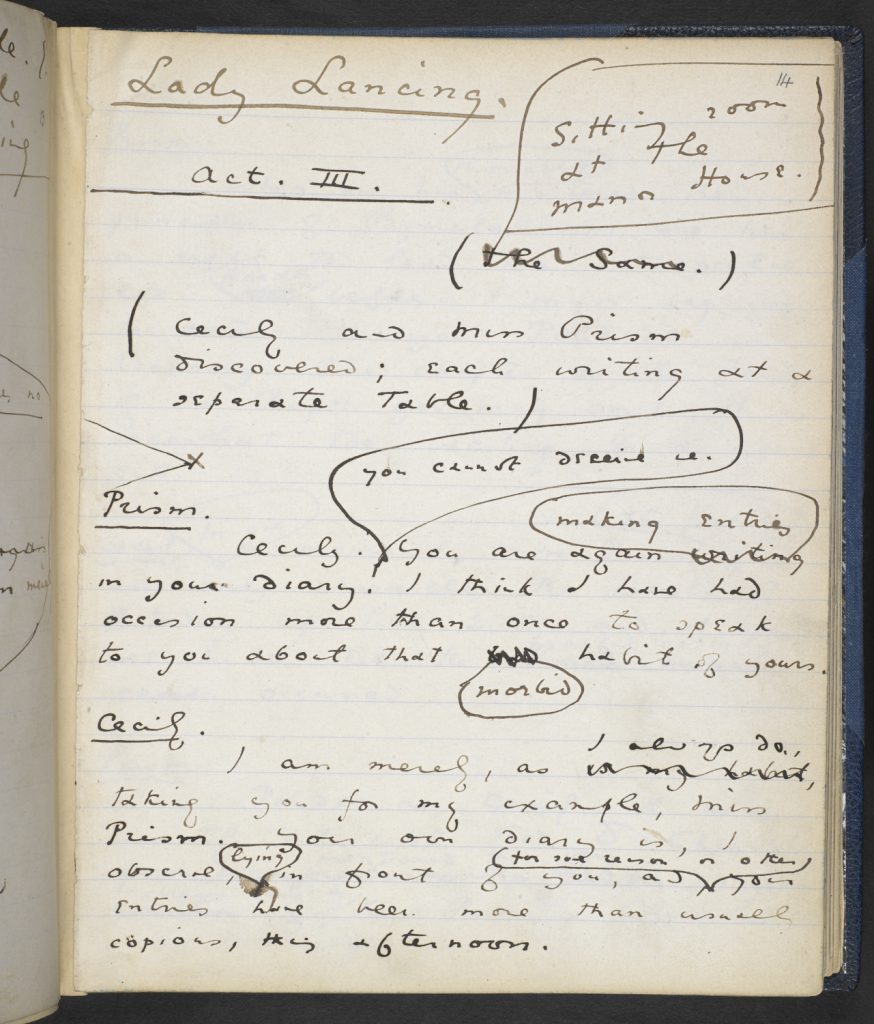

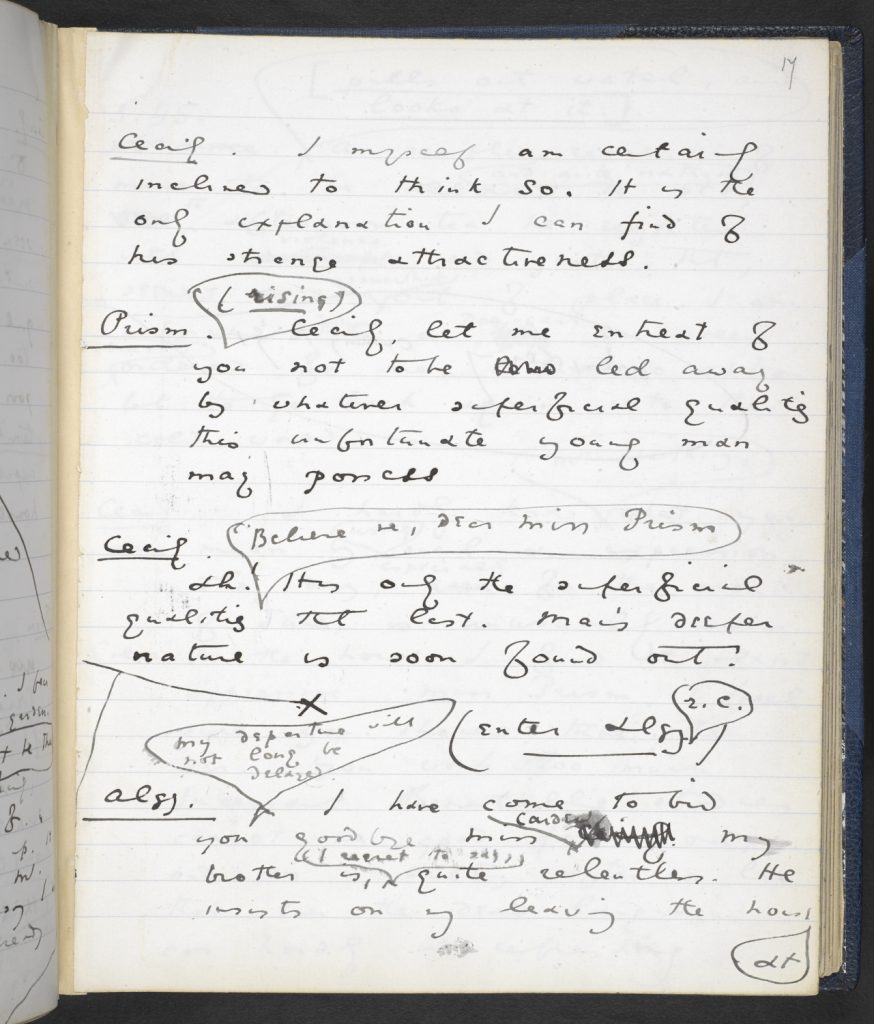

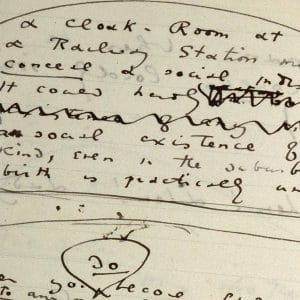

One of my favourite Wilde items is a small and inexpensive notebook which houses very early notes and the development of A Woman of No Importance. The doodles, lists of characters, dialogues, plot lines and streams of consciousness show the beginnings of what is a comical, yet profoundly socially astute play, even for a 21st century audience. I love this notebook because it shows how Wilde wrote, thought and developed. It is a real contrast to some of the later Wilde manuscripts and typescripts for The Importance of Being Ernest, An Ideal Husband, A Woman of No Importance and Lady Windermere’s Fan, which are considerably more worked up, developed and often far neater. I am drawn to this notebook because it shows Wilde’s raw ideas and character notes, before he amended lines and developed plots. The play opened in London on 22 January 1900.

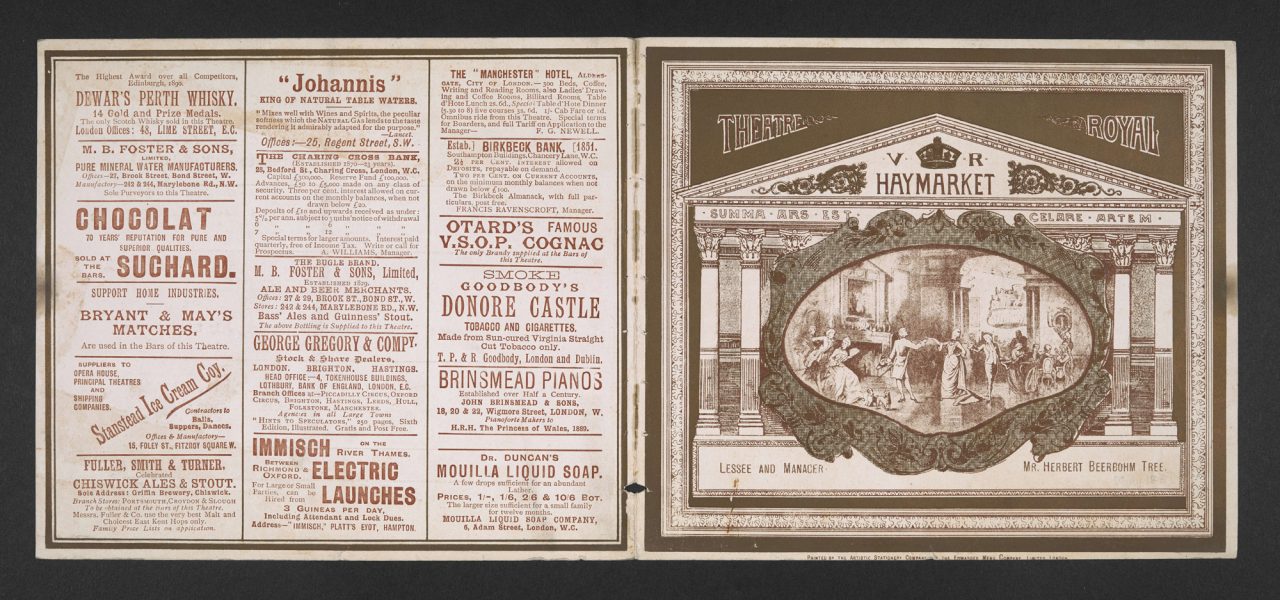

The notebook has a provenance which hints at Wilde’s connections in North America and his tours across the States. The volume was owned by Jerome Kern (1885-1945), an American composer of musical theatre, who wrote songs such as ‘Smoke gets in your eyes’ and ‘The Way You Look Tonight’. Kern was connected to Wilde through the American theatrical and literary agent Elisabeth Marbury, who represented Wilde in both London and New York. Marbury had met Wilde on his first lecture tour of America in 1882 in which he covered subjects such as ‘The English Renaissance’. A subsequent owner of the Woman of No Importance draft was Marjorie Wiggin Prescott (1893-1980), an American book and furniture collector whose significant Wilde collection was sold at Christie’s in 1981. The notebook came to the British Library as part of the Eccles Bequest, which was formed by Mary, Viscountess Eccles (1912-2003), a book collector, philanthropist and member of the American Friends of the British Library. The collection comprises not just highly important Wilde manuscripts but also correspondence, books, portraits and photographs. Within this collection are many of the playbills for original and later productions of Wilde’s plays. It’s these layers of archive and experience which make studying Wilde’s original collection material so exciting.

What does the typewritten manuscript tell us about Wilde and his writing process?

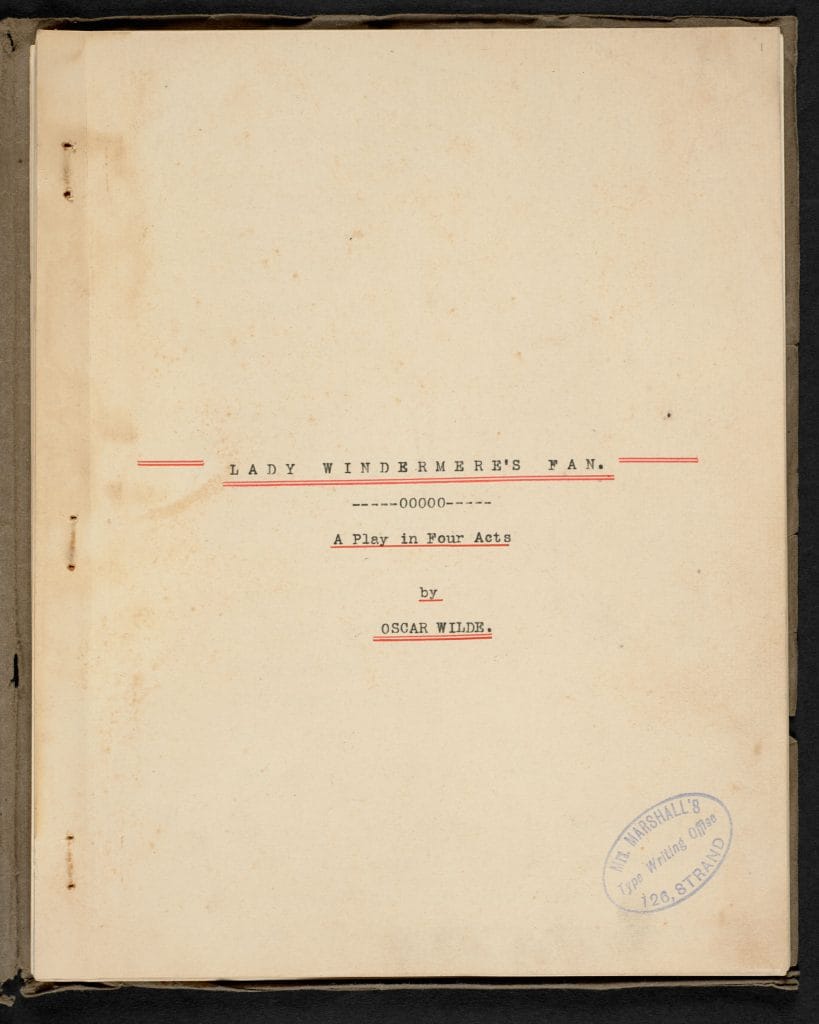

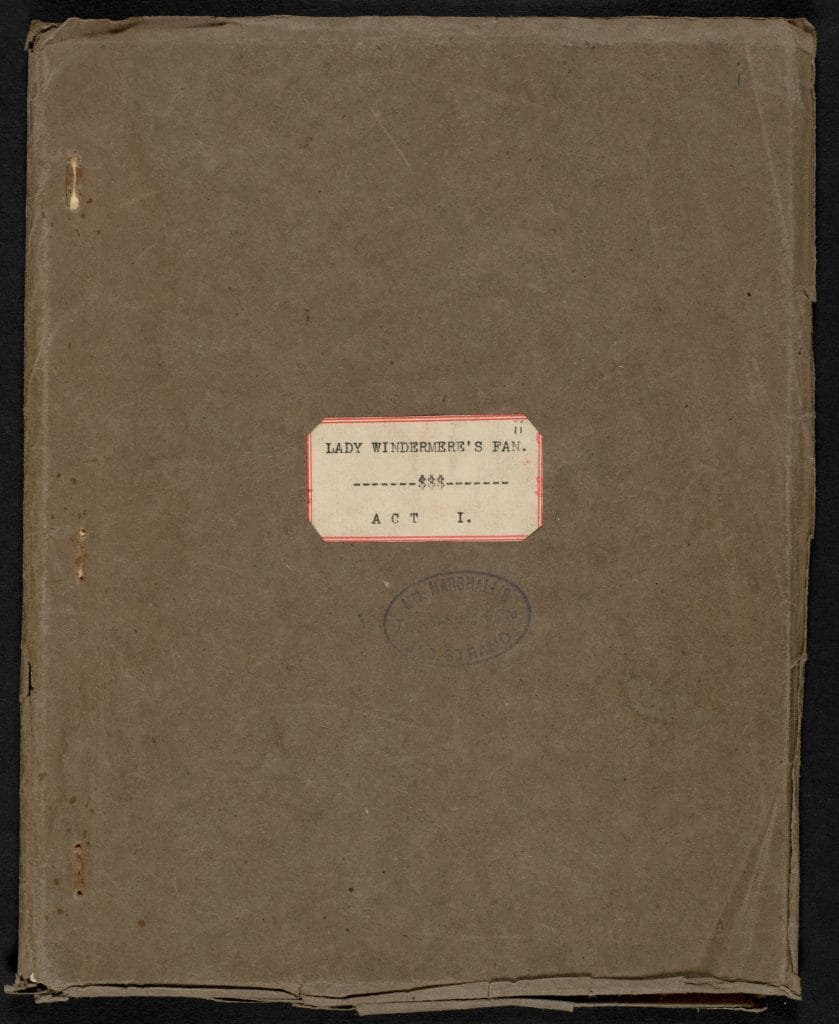

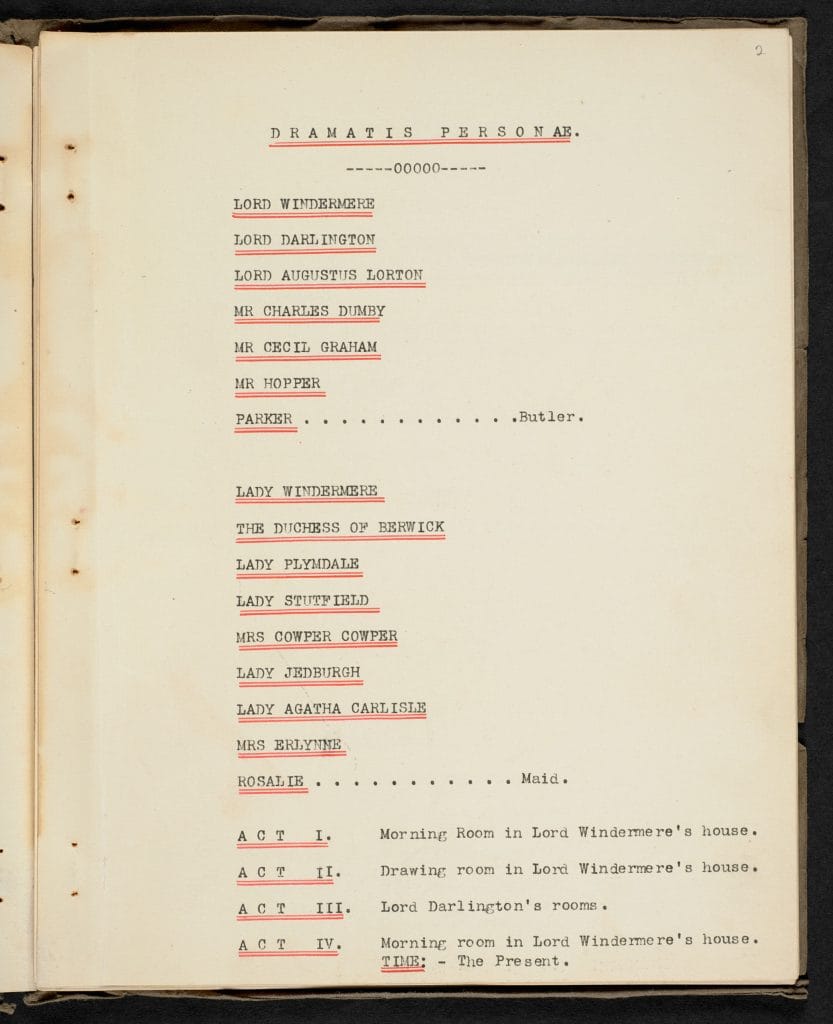

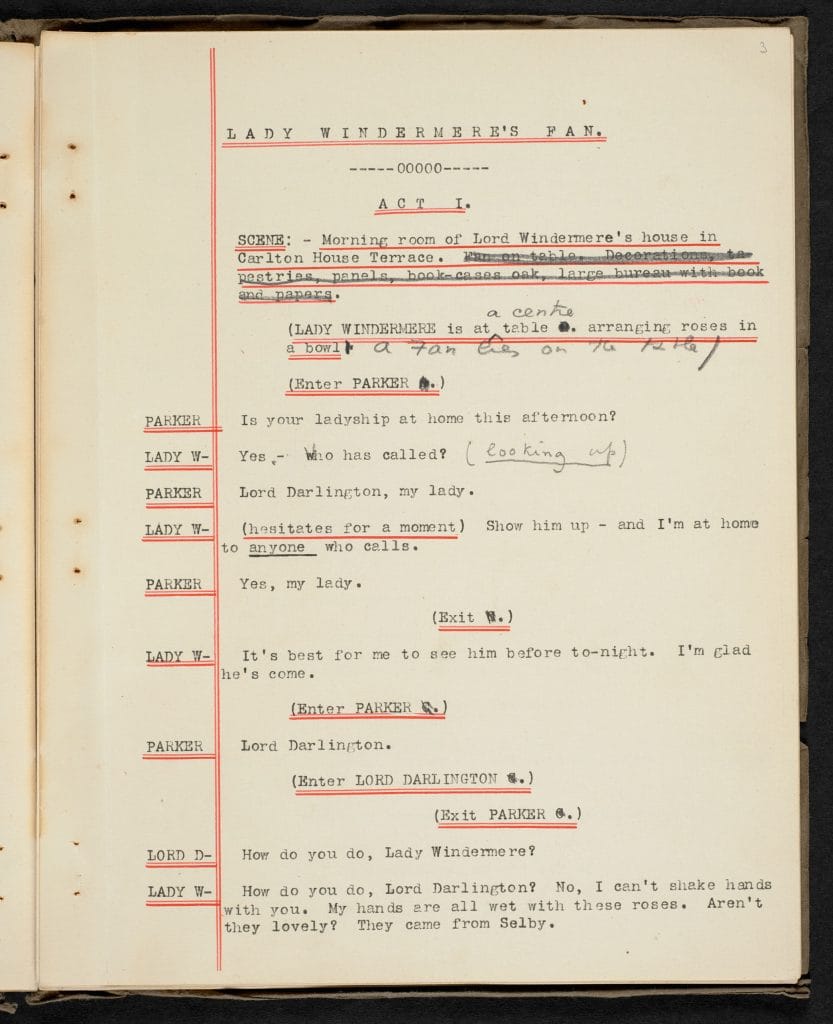

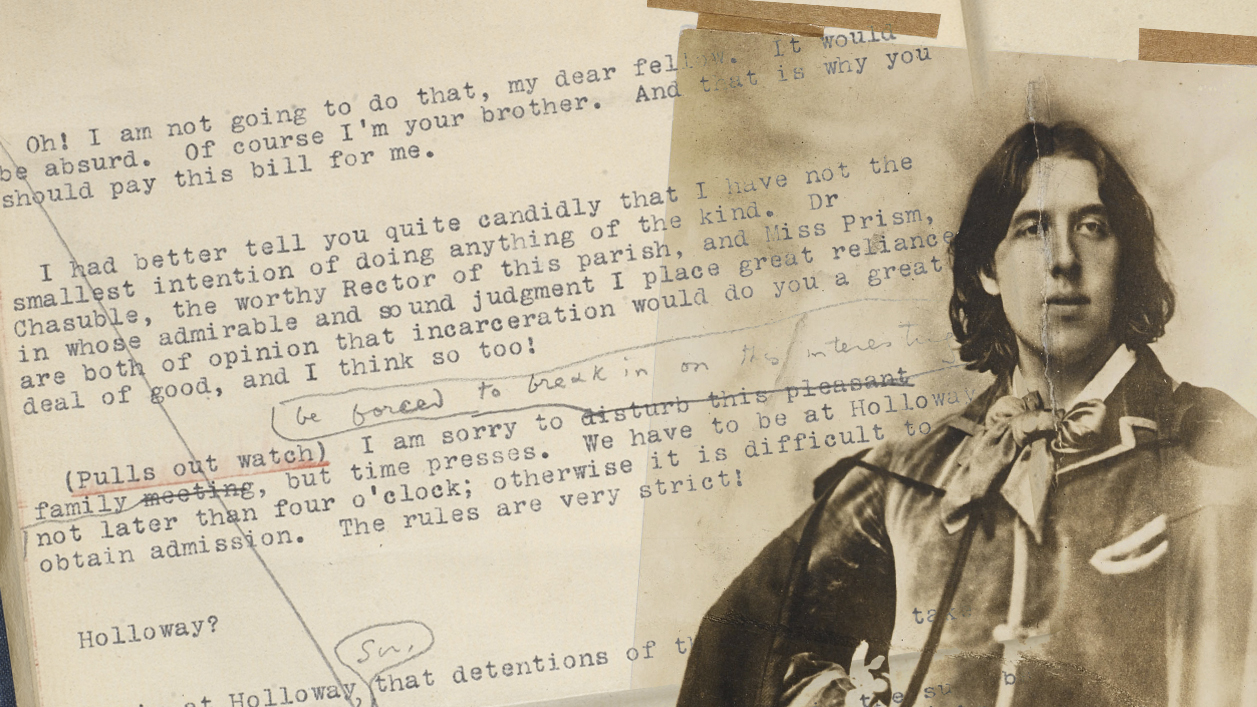

Wilde developed his rough drafts into more finished play scripts, which he then submitted to be typewritten so he could make further amendments and corrections. The British Library has the original manuscript drafts and the typewritten second drafts for all of Wilde’s key plays. The typewritten draft would have been returned to Wilde and this would be the first moment he would have seen his play start to look like a working script. On each typewritten script is the stamp ‘Miss Marshall’s type writing office, 126 Strand’. 126 Strand, London almost opposite to where Wilde lived at 13 Salisbury Street from 1879. The physical proximity of Wilde to his typists and to the theatres in which his plays were first staged, cites the creation and development of many of his plays into a narrow geographical window.

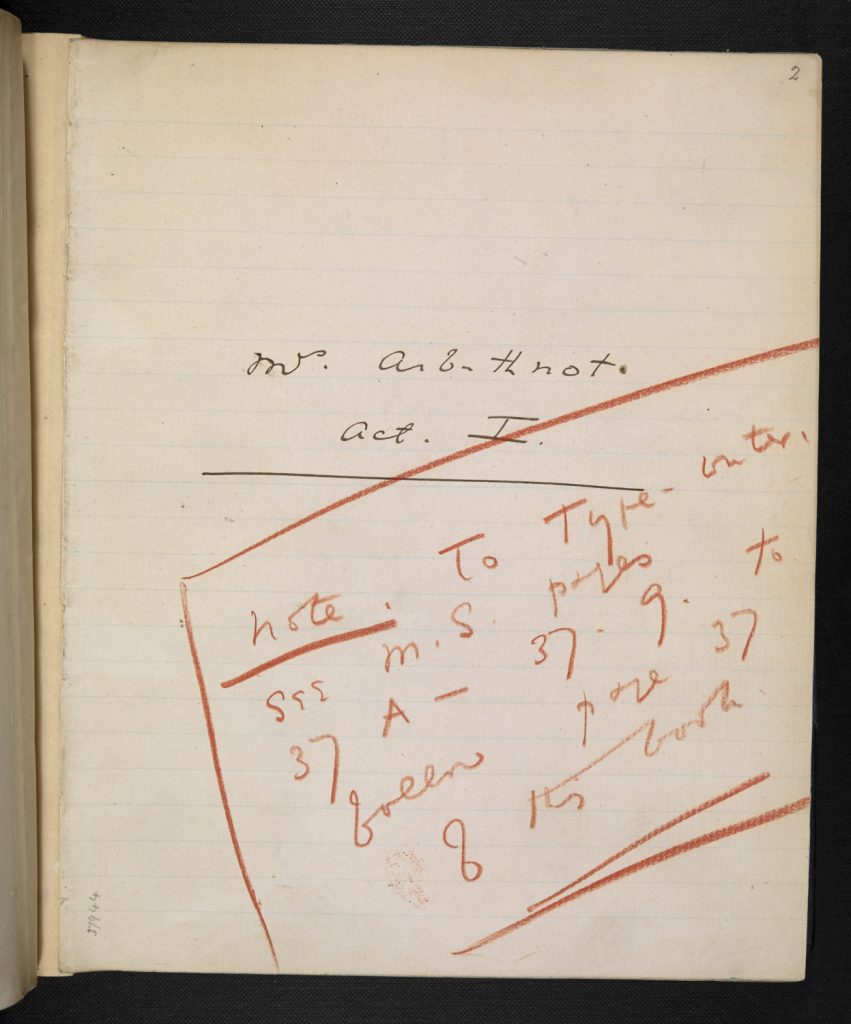

In some drafts, Wilde made notes to the typists in the same manner he used when inserting actor’s lines so that the two worlds somehow become blurred. But this stage in the production was not meant to be seen by any audience, so now we are in a privileged position to read Wilde’s instructions to his typist on the same plane that he inserted actors’ lines.

When developing his plays, Wilde worked in different mediums: in pencil, ink or with typewritten sheets, in notebooks, on scraps of paper or on rules sheets. This suggests that his writing process occurred in parts and stages and that he was not wed to a single writing format. While some authors relied almost religiously on bound notebooks, and others tore scraps of papers from any source they could find, Wilde’s practice occupied a middle ground. While there is certainly a sense of order, especially in his later drafts, he worked flexibly with whichever writing material he had to hand. In some instances he used red crayon to highlight inserts, in others, black ink or pencil.

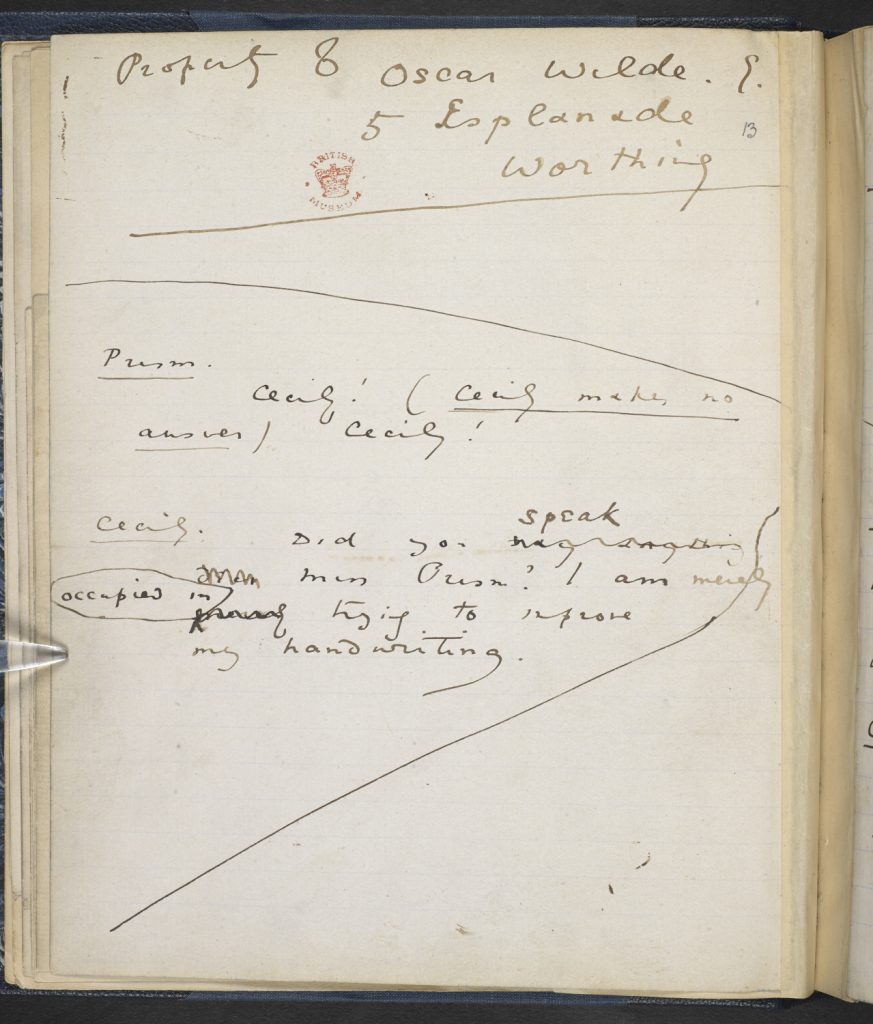

In an early draft of The Importance of Being Earnest the variety of paper size and medium, suggest that Wilde was working with loose typewritten sheets and a bound manuscript volume. A note at the beginning suggests that at least part of the manuscript travelled to the typewriter as it reads ‘Property of Oscar Wilde 5 Esplanade Worthing’. Wilde wrote Earnest while holidaying at Worthing, England, during August 1894.

What do Wilde’s amendments reveal?

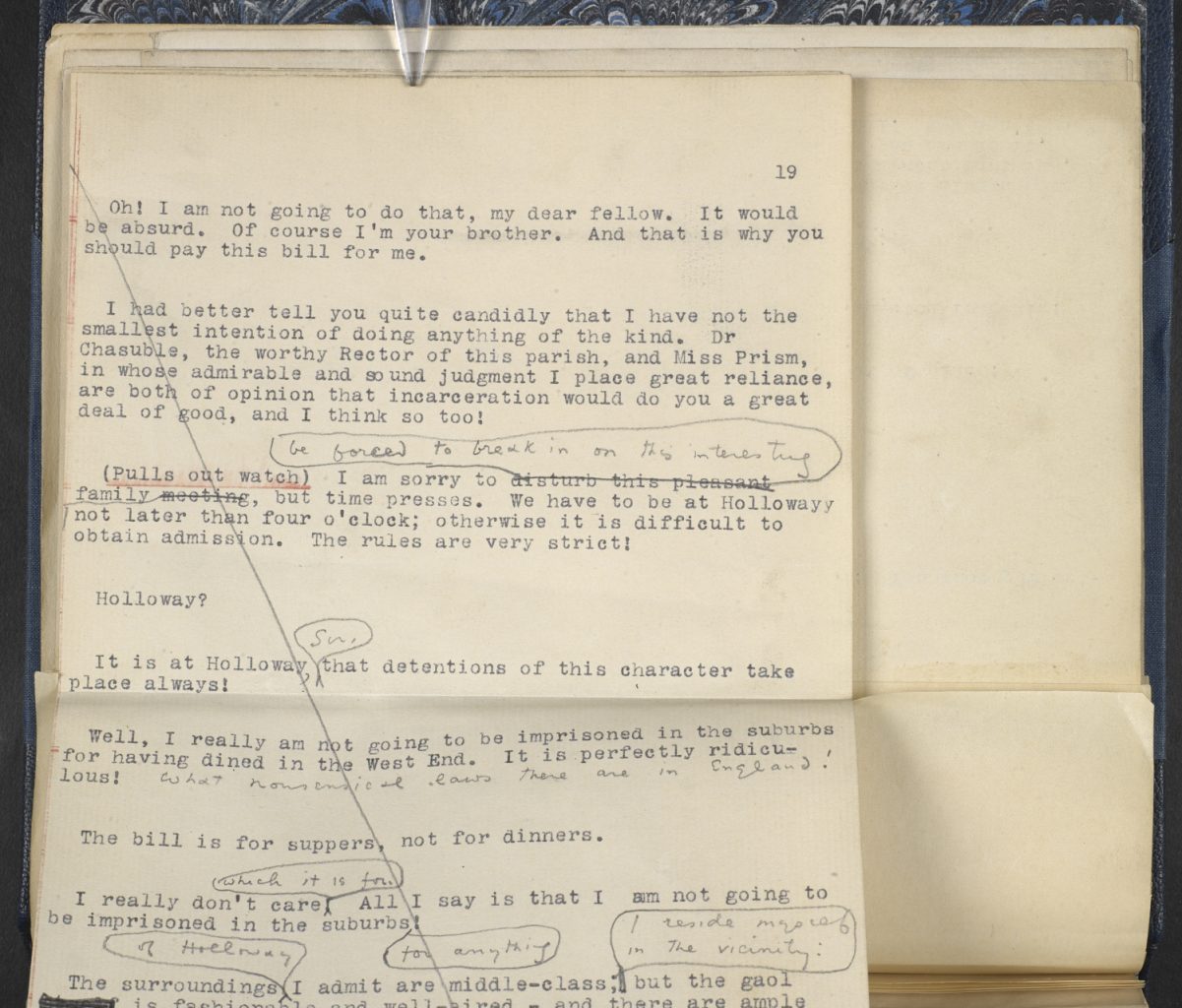

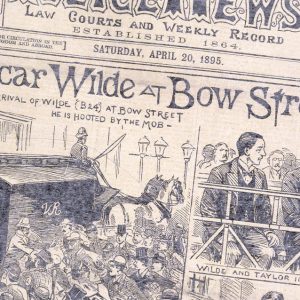

The typewritten part of the volume contains the deleted section in which the solicitor Mr Gribsby attempts to arrest Algernon and incarcerate him in Holloway prison. The scene highlights nervousness about geography and the social implications of location:

“It is at Holloway, Sir, that detentions of this character take place always!

“Well I really am not going to be imprisoned in the suburbs for having dined in the west end. It is perfectly ridiculous. What nonsensical laws there are in England!

“The bill is for suppers, not dinners!

“I really don’t care which it is. All I say is that I am not going to be imprisoned in the suburbs!”

The manuscript folio also reveals changes to what appear to be innocuous lines: “I am sorry to disturb this pleasant family meeting” becomes “I am sorry to be forced to break in on this interesting family meeting . . .”. This suggests Wilde was making changes because of the way lines might sound when performed rather than to alter their meaning or content.

Many alterations, both to stage directions and actor’s lines are inserted as bubbles – as if the actor were speaking and correcting their own line from the stage. The use of these bubbles conjure speech and sound as well as movement, giving a sense of the play in three dimensions even at draft stage. In draft form, the space between stage and script is diminished.

Why are the British Library Wilde collections important?

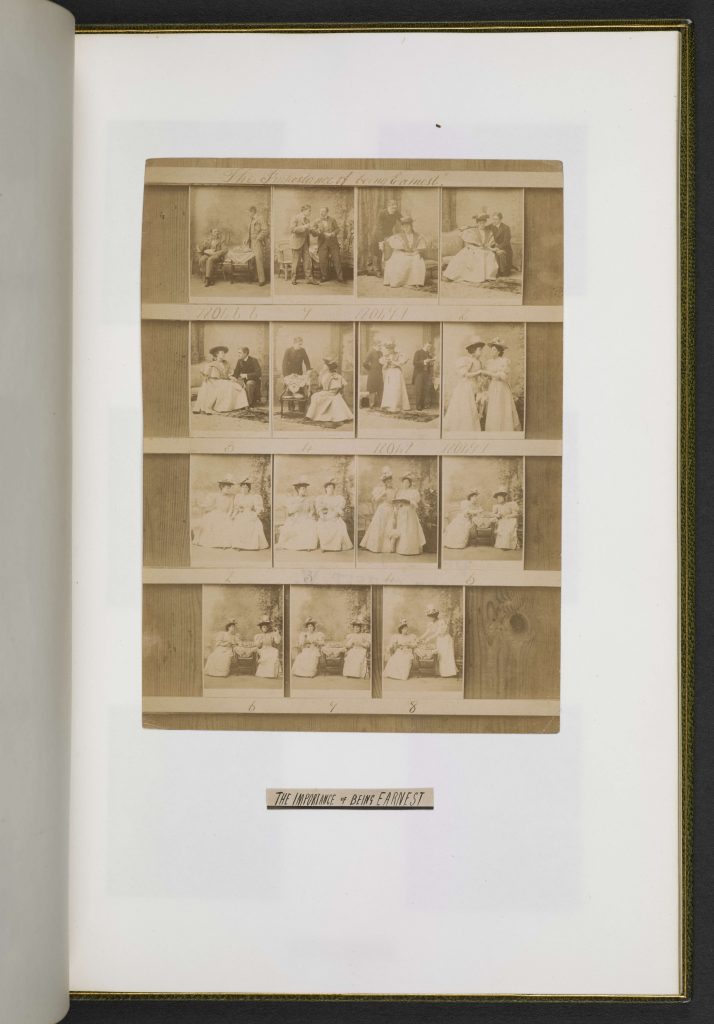

From early draft to finished production and all the stages in between, the British Library Wilde collections allows readers to see how Wilde developed his plays. Aside from the manuscripts and typescripts which Wilde corrected and developed, the British Library holds original photographs of early productions of The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde’s third play, which opened on Valentine’s Day 1895 at St James’s Theatre. Images of the 1895 production allow us to glimpse what Wilde would have seen when his play was first performed. These photographs represent the early moments when audiences saw this play for the very first time. They show Irene Vanbrugh as Gwendolen Fairfax and George Alexander as Jack Worthing. George Alexander was also the manager of St James’s Theatre where Lady Windermere’s Fan opened in 1892.

Considering that Earnest is almost continually in performance around the world be it in amateur productions or in the West End of London, to see the play as new and fresh and hitherto unknown is somewhat of a revelation to a 21st century audience. How can there have been a time when Earnest was unknown?

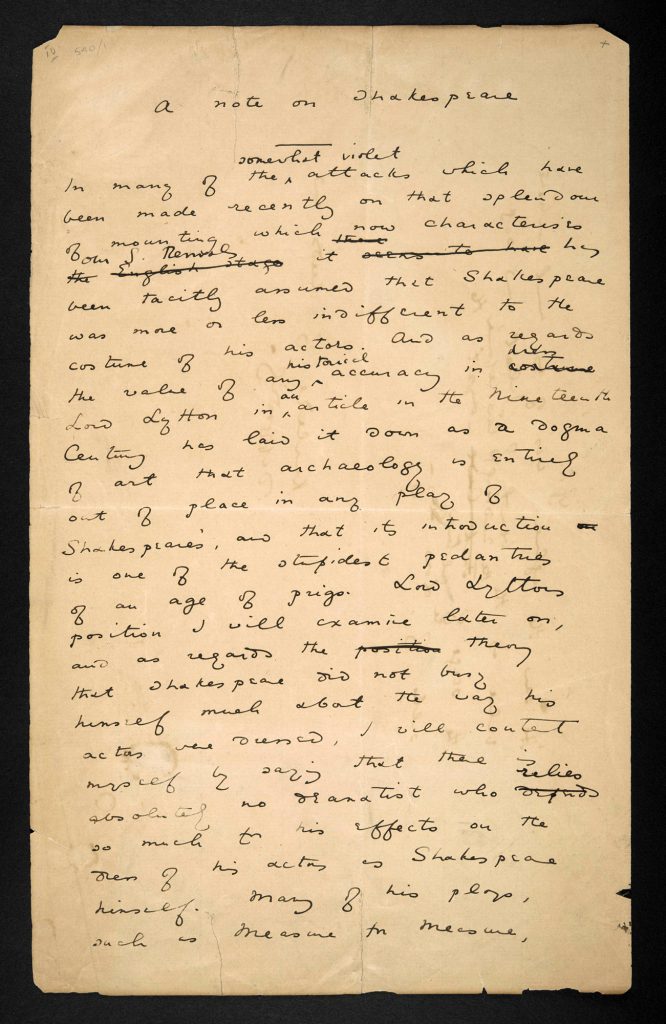

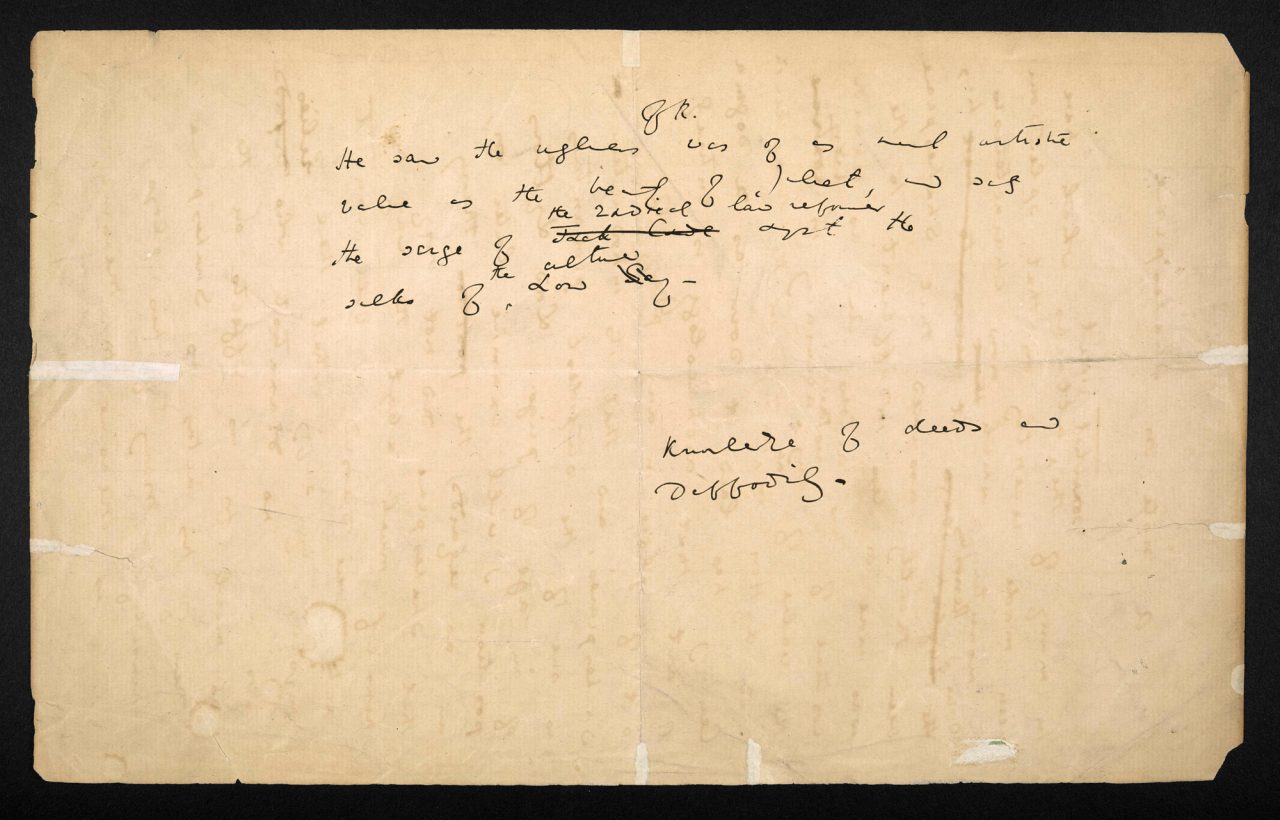

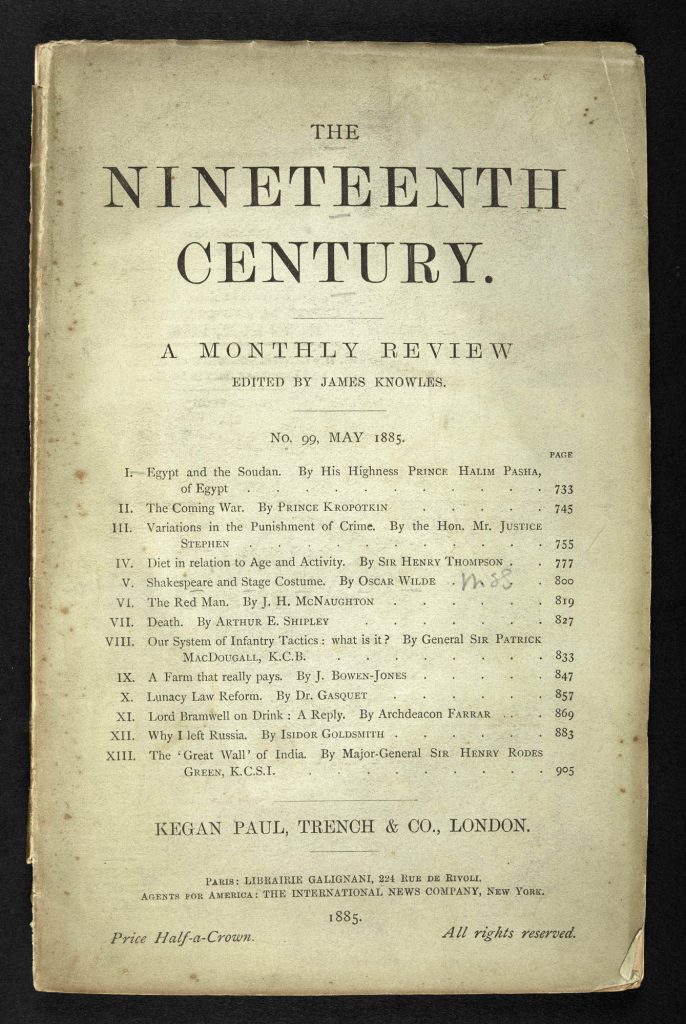

Yet Wilde as playwright is but one facet of his character. He was a prolific essayist, writing on socialism, interior design and the Elizabethans, among other subjects. Many of his essays were published or performed, as with his Elizabethan and Design lectures which he toured across America in 1892. One published essay ‘Shakespeare and Stage Costume’ demonstrates Wilde’s interest not just in writing for theatre, but on production, historic costume and effect.

Wilde’s words live in many different formats and continue to be encountered in varying spaces. It is our hope that by making more of his original manuscript material fully available online, readers around the world can engage with a hitherto under-explored aspect of his incredibly varied work.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Alexandra Ault

Alexandra Ault is Lead Curator of western manuscripts from 1601-1850 which includes important items from English literature and world history. She is also Lead Curator for the British Library in China project that involves lending some of the Library’s most important treasures from English literature to a number of exhibitions across China. Her particular areas of research interest are nineteenth-century publishing, the relationship between manuscript and print, and the ‘life’ of the literary manuscript during and after writing.