A close reading of ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’

Santanu Das examines the crafting of one of Wilfred Owen’s most poignant poems, ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, and shows how Owen’s war poems evoke the extreme sense-experience of the battlefield.

Composition and the trace of hands

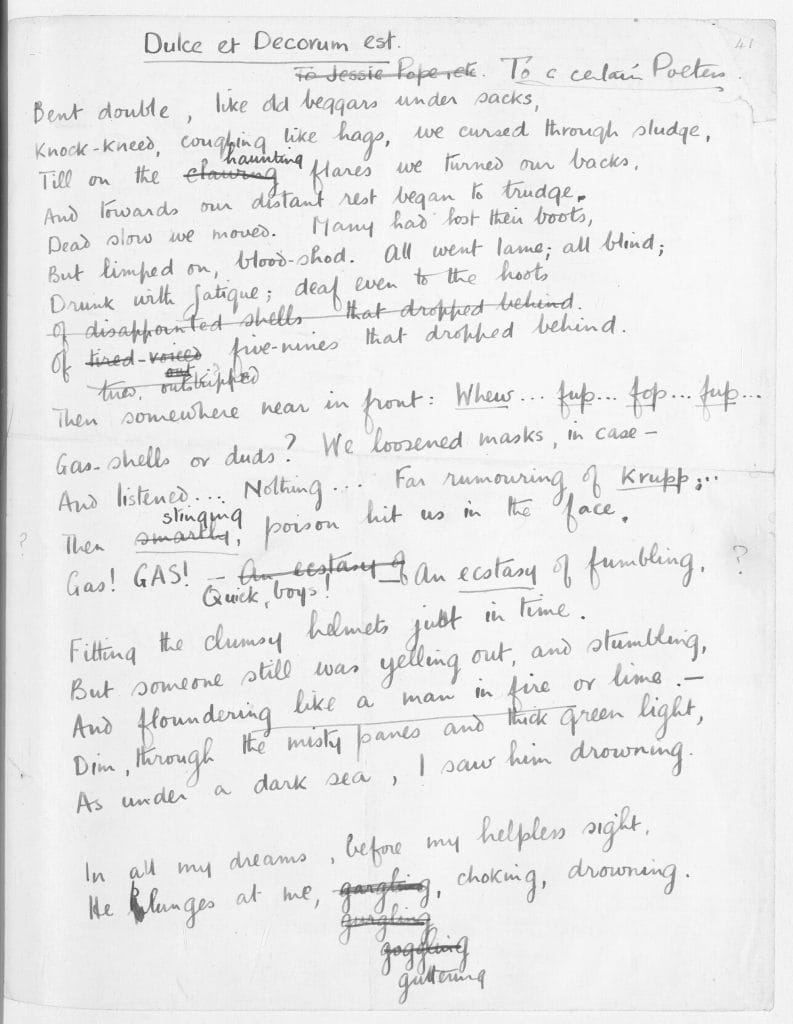

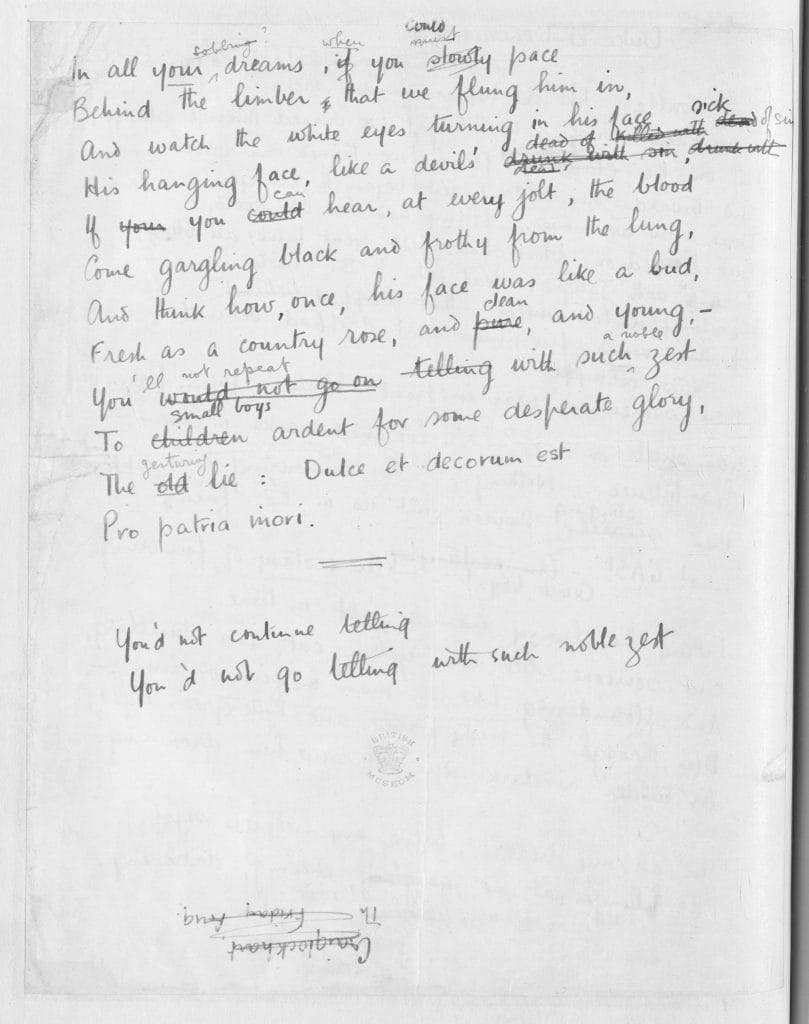

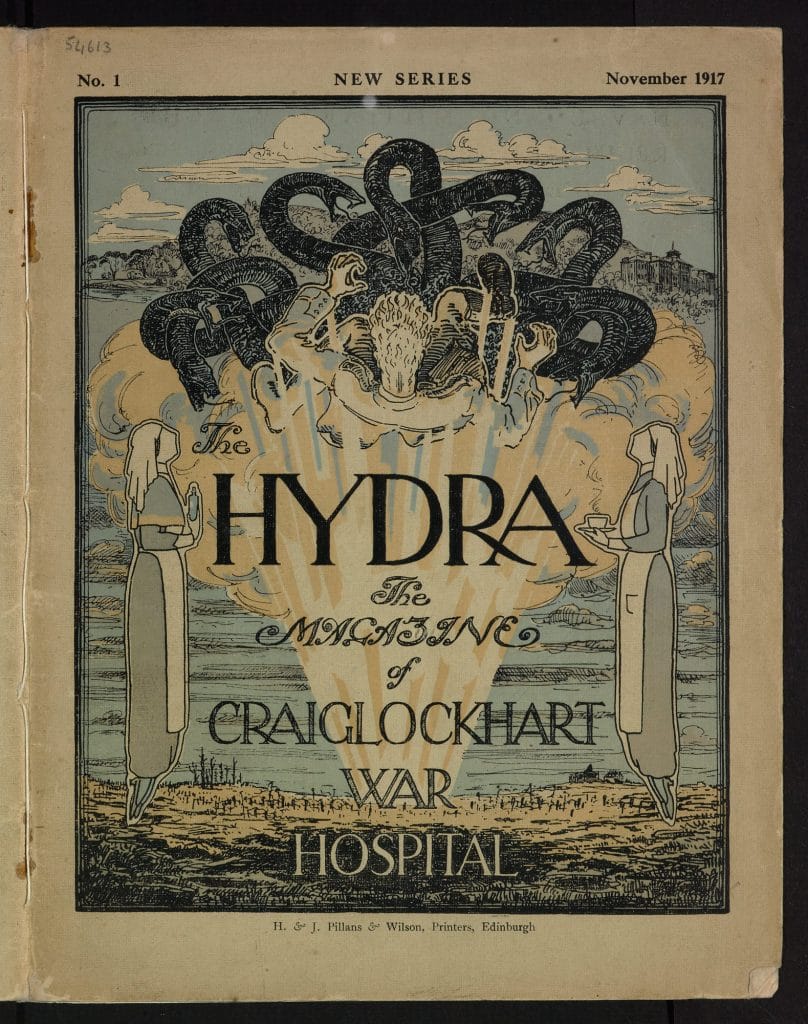

On 16th October 1917, Wilfred Owen wrote to his mother Susan: ‘Here is a gas poem, done yesterday, (which is not private, but not final). The famous Latin tag [from Horace, Odes, III, ii. 13] means of course It is sweet and meet to die for one’s country. Sweet! and decorous!’.[1] At the time, he was recovering at the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh where he famously met fellow officer-poet Siegfried Sassoon. Owen would revise the poem, ‘not private but not final’, in Scarborough or Ripon between January and March 1918 and go through several drafts.

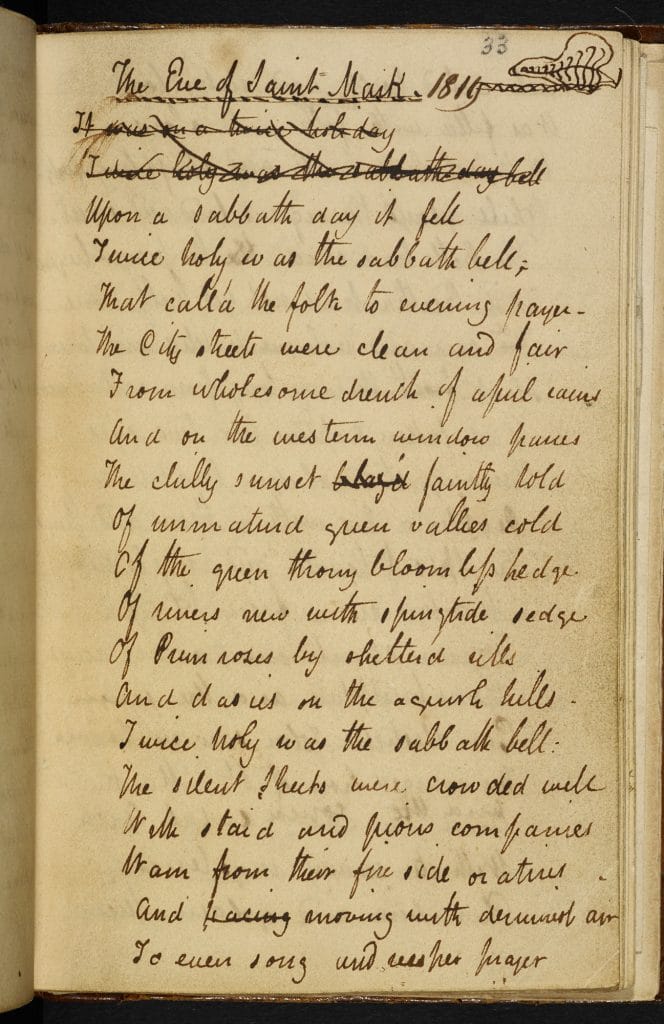

One of the most important – and poignant – manuscript-drafts of the ‘gas poem’ is now housed in the British Library. In September 1911, the eighteen-year old devotee of John Keats had visited the old British Library reading room at the British Museum. There he spent two hours in ‘subdued ecstasy’ as he read ‘two letters of J.K.’s and two books of manuscript poems’ and identified with his mentor’s hand: ‘[His] writing is rather large and slopes like mine – not at all old fashioned and sloping as Shelley’s is. He also has my trick of not joining letters’.[2] Today, the manuscript of ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ teases us with its combination of meaning and materiality as we find his ‘large and sloping’ hand thinking and feeling its way through the shape and sound of words with many crossings-out and revisions into his ‘charred’ senses. At one point, Owen replaces the word ‘clawing’ with ‘haunting’. The poem itself is a ‘haunting’, marked as much by his memories of the front as by his growing sense of duty as a war-poet: ‘My subject is War and the Pity of War. The poetry is in the pity’. Yet, in a paradox characteristic of the First World War, the war-haunted document is also an ode to literary friendship forged at Craiglockhart. The manuscript bears traces of Sassoon’s hand too, brushing against Owen’s, pencilling in suggestions, meeting ours, as we leaf through the manuscript – each alone.

Owen and the theatre of pain

Wilfred Owen is considered the quintessential anti-war poet, and with abundant reason. After three weeks at the front, Owen wrote to his mother, ‘I have not seen any dead. I have done worse. In the dank air, I have perceived it, and in the darkness, felt’.[3] Horrified by what he had seen and felt, he refashioned poetry as testimony, as missives from the trenches, to ‘warn’ future generations. But Owen the pacifist icon can come in the way of fully understanding Owen the poet. The power of his finest poems lies not just in its anti-war polemic or realism or even pity (each of which deeply informs his poetry) but in something far more subtle, more risqué, more disturbing.

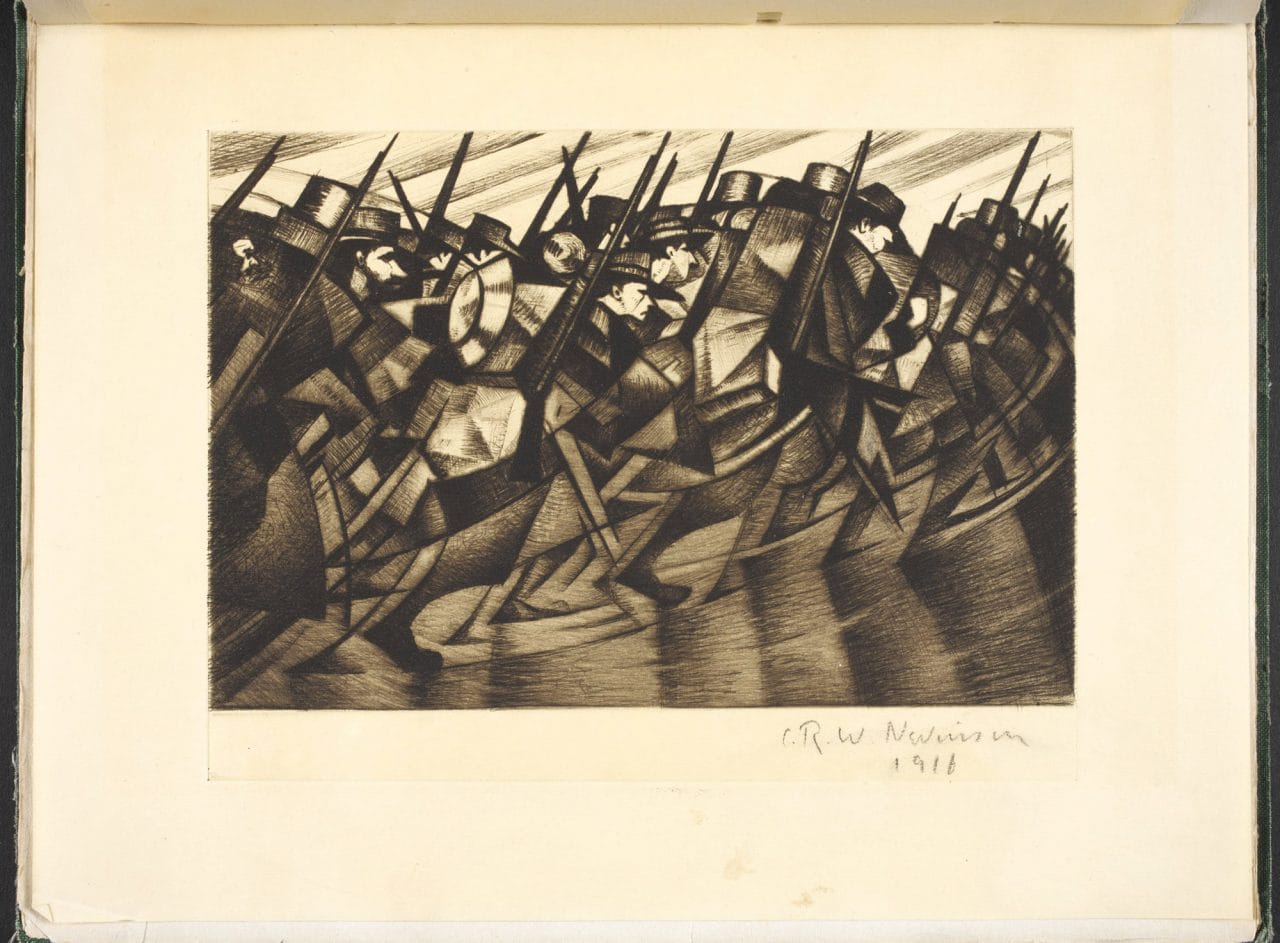

Of all the war poets, he is the one who repeatedly evokes moments of extreme sense-experience on the battlefield through an eerie combination of sound, affect and violent imagining, drawing us deep, Caravaggio-like, into scenarios we would otherwise flinch from – moments when limbs are sliced off (‘limbs knife-skewed’, ‘shaved us with his scythe’, ‘the arm that drips’, ‘Legless, sewn short at elbow’), the flesh is ripped apart (‘shatter of flying muscles’, ‘Ripped from my own back/ In scarlet shreds’) or the mouth starts bleeding (‘I saw his round mouth’s crimson deepen as it fell’).[4] A strong Protestant ethic, the tradition of fin de siècle decadence, repressed homoeroticism and the horrors of trench warfare combine to produce these violent images: the male body, that cannot be touched and loved at the time, is repeatedly mutilated in his poetry. Acutely sensitive since his childhood to the body, its vulnerability as well as its capacity for pleasure, he weaves linguistic-tactile fantasies around the very paroxysm of pain. A visceral thrill as well as an acute physical empathy constitute the body in pain in Owen’s poetry, hovering around moments when we no longer know where the is ends and the was begins. ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ marks the apogee of such a process.

‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ is possibly the most famous ‘war poem’ which, since the First World War, has come to mean ‘anti-war’ poetry: the image of a young man coughing up his lungs remains the classic example of ‘war realism’ in its full-frontal shock value. Yet, to read the text as ‘history’, as a transcript of trench-horrors, is to ignore its singularity as poetry. Neither the transparent envelope of trench experience nor just language whispering to itself about itself, ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ is one of those primal moments in the history of not just English but world poetry when lyric form bears most fully the trauma of modern industrial warfare.

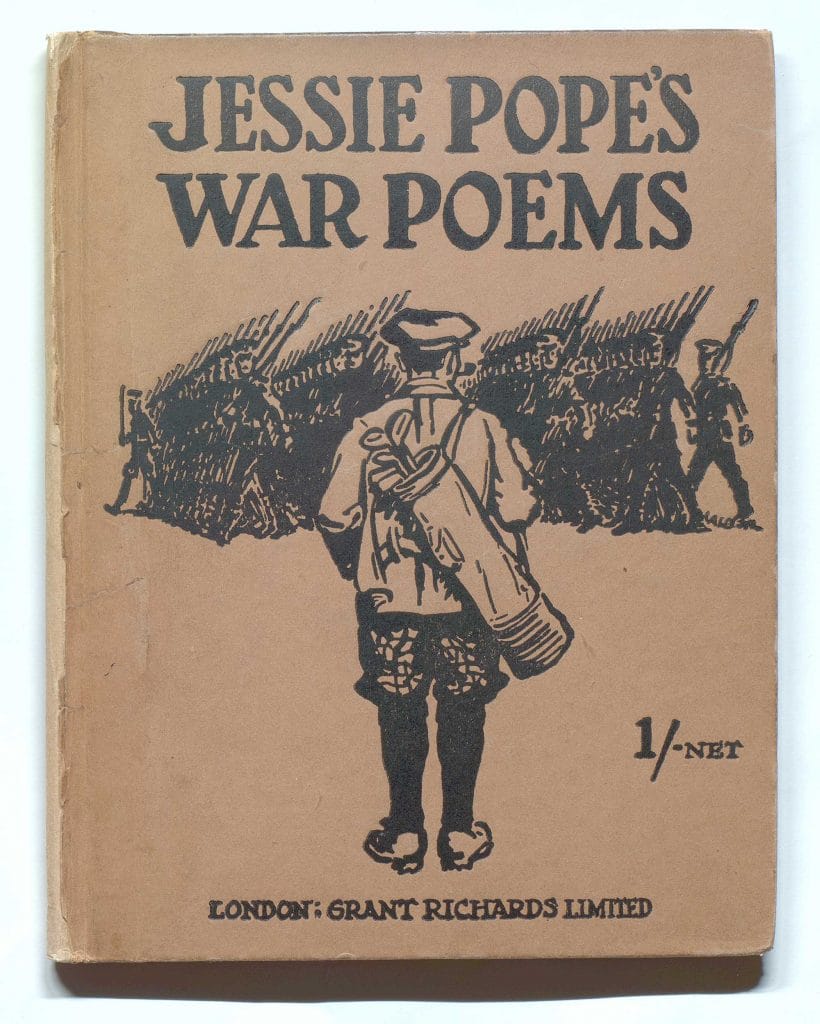

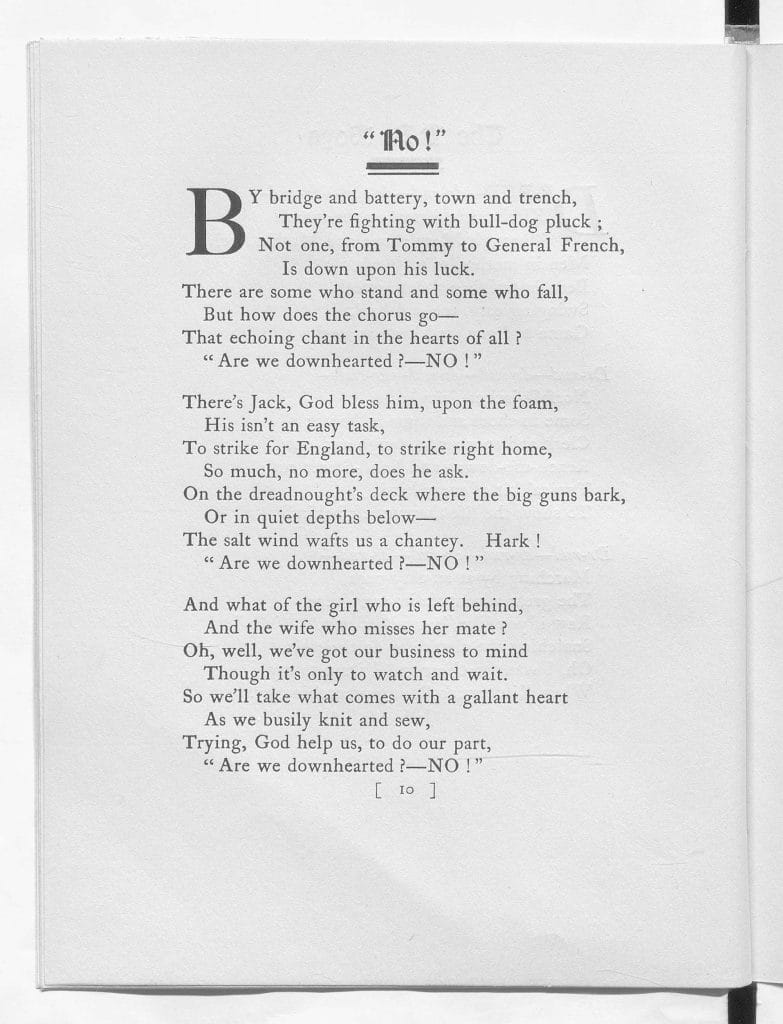

In the above draft-manuscript, the poem was originally dedicated, with bitter irony, to ‘Jessie Pope etc’ which is then crossed out and revised as ‘To a certain Poetess’. Nonetheless, the dedication, rather unfairly, has consigned the author of sentimental, patriotic and popular volumes such as Jessie Pope’s War Poems (1915) to eternal shame in the annals of First World War history. Jessie Pope is possibly the addressee (‘My friend’) too in the final stanza, though Owen could have meant writers of heroic war verse more generally, particularly those producing wartime variations on Horace’s hallowed theme.

In sharp contrast, in ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’, he sets the war-ravaged body and mind against the abstract rhetoric of honour and sacrifice. In the process, he plays three separate experiences – a night march, a gas attack and traumatic neurosis – along an almost single vertical bodily axis as he traces the very pulse of pain as it moves from exposed feet in the first stanza to exposed nerves in the final one. Time is held in suspense as one nightmarish experience follows, and blurs into, another until the final part of the poem is literally about a nightmare: the repetitive rhythm of the march gives way to the traumatic compulsion to repeat.

At first glance, the poem may seem to bear out the theme of ‘passive suffering’ which led W B Yeats to object to war poetry (‘passive suffering is not a theme for poetry’) and attack Owen in particular (‘all blood, dirt & sugar stick’).[5] When Yeats witheringly notes that ‘somebody has put his worst & most famous poem in a glass-case in the British Museum’, the object of disdain may well have been the manuscript of ‘Dulce’! But any simple notion of ‘passivity’ that he reductively levels at Owen is countered in the poem not by the ‘tragic joy’ that Yeats privileged but by an altogether new kind of aesthetic and empathy.

Articulate flesh and the body of sound

Pain and theatricality are often the twin components in Owen‘s poetry. In many of the poems, the opening line – often even the opening words – propel the body into action: ‘Move him into the sun’ (‘Futility’), ‘Cramped in that funnelled hole’ (fragment with the same title), ‘So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went,’ (‘The Parable of the Old Man and the Young’), ‘He dropped, – more sullenly than wearily’ (‘The Dead-Beat’), ‘Sit on the bed. I’m blind, and three parts shell’ (‘A Terre’), ‘Halted against the shade of a last hill’ (‘Spring Offensive’).[6] Similarly, in ‘Dulce‘, the body is already there, entering the poetic canvas in medias res:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, out-stripped Five-Nines that dropped behind. [7]

The opening lines, through their alliterative and visual force, situate the bodies in our field of perception: bent-double, knock-kneed, the soldiers continue to limp with their bloodied feet as iambs and trochees straggle within the pentameter in order to keep up with the somnambulist rhythm of the march. Underneath ‘blood-shod’, one can hear the pararhyme ‘bloodshed’. However, instead of blocking out the visual horrors through decadent music, as in ‘Greater Love’ or ‘The Kind Ghosts’, the sound here acts out the opening image in ‘doubling’ back on itself (‘Bent double, like old beggars’) and sets in motion a pattern of labials and sibilance which would underpin the rest of the poem. ‘Double’, coupled with ‘old’, also anticipates one of the most powerful uses of ‘d’ to be found anywhere in English poetry: the consonant not only weaves itself into the end-rhymes and the key images (‘drunk’, ‘deaf’, ‘drown’, ‘dreams’) but its accretive intensity is central to the denunciatory polysyllabic force of ‘The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est’.

Sound plays a particularly important role in a poem that climaxes on a macabre contrast between tongues: the lacerated tongue of the soldier and the grand polysyllabic sound of the Latin phrase as he plays on the two meanings of ‘lingua’ (in Latin, it means both tongue and language). If the heavy, monosyllabic rhymes of the first stanza (sacks/backs, sludge/trudge)are reminiscent of Sassoon’s war realism, there is a more intimate sound pattern that his much-idealised soldier-mentor never manages to achieve. This is the sound of vowels – the ‘e’, ‘o’ and ‘u’ sounds (knock-kneed, coughing, cursed, sludge, our, trudge, lost, blood-shod, went, even, outstripped, dropped) – which evokes the body in pain and culminates in the noises of the retching body in the final lines. The sounds of the similes (‘beggars’, ‘hags’) soon metamorphose into the central reality (‘gargling’) of the poem.

Mustard gas corrodes the body from within. In Owen‘s depiction, the testimony of the gas attack moves accordingly from visual impressions to guttural processes; from sounds produced between the body and the world – fumbling, stumbling, flound’ring, drowning – to sounds within the body: guttering, choking, writhing, gargling. While war protest is habitually written through a language of wounds, Owen’s visceral imagination takes it a step further, a movement horrifically apt for our own times of biological and chemical warfare. A striking piece of war realism, the poem also tunnels into his private medical history. The adolescent Owen was obsessed with his health and Jon Stallworthy in his classic biography notes how he began to see himself as ‘a Chattertonian figure, consumptive and impecunious in an attic’.[8] The hypochondriac adolescent who regularly coughed up phlegm and wrote at length about it to his mother now not only recognises his past self in the troops ‘coughing like hags’, but he will now forever haunted by the spectre of a man coughing up his lungs. If ‘Exposure’ writes the horrors on the surface of the body through the ‘fingering stealth’ of snow, ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ is a poem obsessed with the insides of the body.

‘An ecstasy of fumbling’

The night-march gives way, abruptly and dramatically, to the terror of a gas attack. If the ageing civilian painter John Singer Sargent, in his famous commemorative painting Gassed (1919) presents us with an orderly file of gassed and blinded soldiers – all tall and blond and moving by touching the man in front – Owen the young combatant plunges us into the thick of action through repetition, capitalisation and exclamations:

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

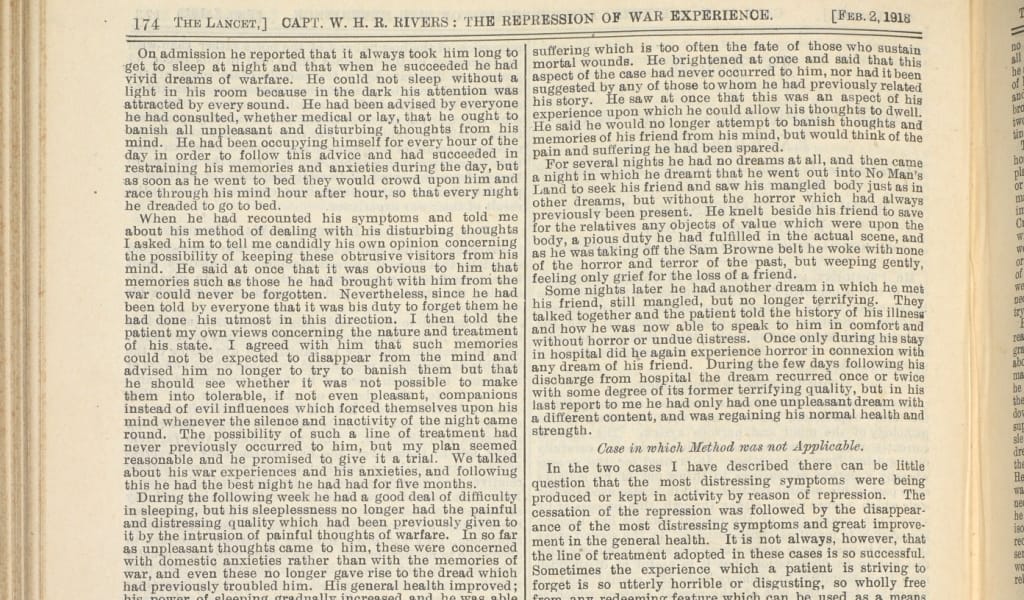

Sassoon, on reading the manuscript, put a question mark beside ‘ecstasy’ but Owen, gaining in confidence, seems to have ignored this demurral. The word remains a challenge to the transparency and realism of the poem, and to critical interpretation. On 19 January, 1917, Owen wrote to his mother how, while scouting, he ‘got overtaken by GAS’.[9] How can a gas-attack produce ‘ecstasy’? Coming from the Greek word ekstasis literally meaning ‘a standing outside of oneself’ [ek – out of, stasis – a position, a standing), the word can also suggest a similar retrospective release of energy in the act of writing – the temporal gap and change of roles from victim of the attack to witness/survivor evoked through the medial pause and the intervening dash – as Owen relives the moment at Craiglockhart in October 1917?

In one of his letters, Owen describes the ‘extraordinary exultation’ of going over the top, and seeing the ground ‘all crawling and wormy with wounded bodies’, feeling ‘no horror at all but only immense exultation at having got through the Barrage’.[10] After the first split-second moment of utter panic – evoked through spondaic acceleration and the monosyllabic exclamations – is there a momentary ‘ecstasy’ at the hope of survival as the gas masks are fitted on? Or is ‘ecstasy’ used to suggest the frenzied, nervous energy of the moment, a state of bodily extremity where terror and exhilaration are fused and confused, a psychosomatic variation on what Edmund Burke called the ‘sublime’? Or, to have an interpretation closer to the times and to Owen’s sensibility, one can turn to Sigmund Freud who, in one of his essays on sexuality, noted that ‘feelings of apprehension, fright or horror’ have a ‘sexually exciting effect’ and that ‘all comparatively intense affective processes, even terrifying ones, trench upon sexuality’.[11] Yet, in a poem that explores the complicity of language in violence – the dangers of Horace’s ‘sweet’ phrase [12] – the word ‘ecstasy’ may bear, at an unconscious level, traces of the perverse narrative impulse itself: poetic language, asked to describe violence, touches itself instead through alliteration (‘s’, ‘l’, ‘f’), echo (ecstasy/clumsy/misty) and the rhyming peal of the extra foot (‘fumbling’, ‘stumbling’, ‘drowning’), replacing real-life horror with linguistic jouissance. Owen, while criticising the ‘sweetness’ of a particular poetic tradition, seems to be trapped in the ‘sweetness’ of the lyric form himself.

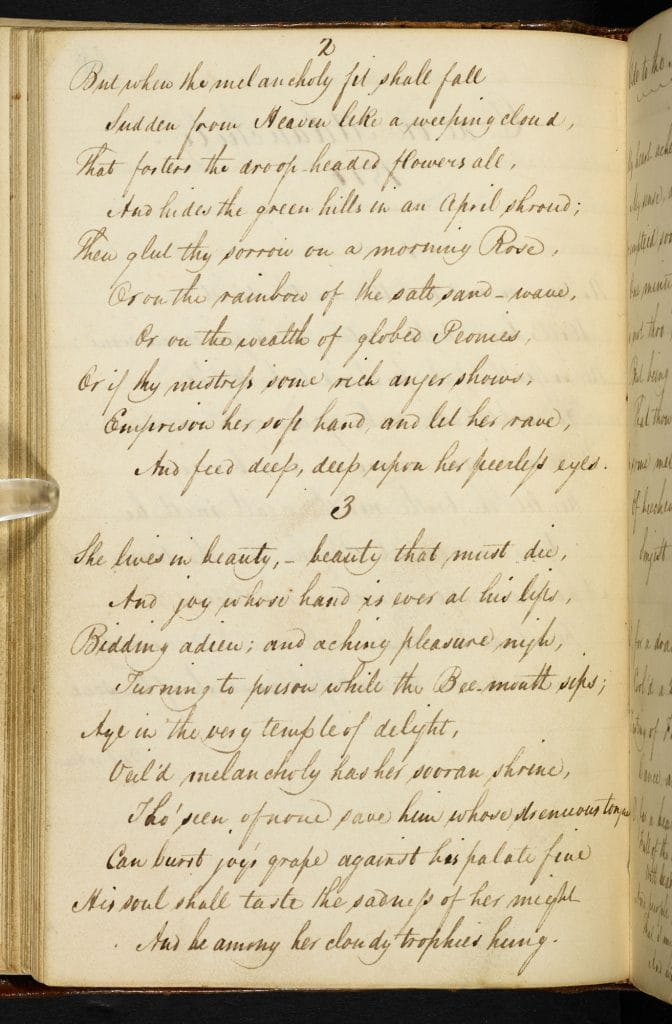

This lyric excess, resulting from Owen’s immersion in fin de siècle English and French poetry, is particularly distressing when the subject of the poem has literally lost his tongue. It raises questions about the relation between art and violence: one is reminded of Sargent’s eerie use of chiaroscuro in Gassed where the light almost perversely clings to the soldiers who can no longer see. In Owen, the light seems to have thickened into an almost tactile space (‘thick green light’) perceived through the celluloid windows of the British Smoke Hood – a rudimentary form of gas-mark – as details from the trench-life are harnessed into this visual-aural-haptic drama. Unlike Sargent, Owen is also grimly realistic: the imagery and much of the music are mined out of morbid physical details – yell, gutter, choke, writhe, gargle, froth-corrupted – and reach their grotesque climax in the visceral intimacy of ‘lung … cancer … sore … tongue’. The realism is stark and shocking: this is poetry as exposure, as pity, as acutely political. At the same time, ‘vile incurable sores on innocent tongues’ is also a rewriting of Keats’ ‘palate fine’, as Owen relocates Keatsian sensuousness in the face of industrial warfare.

Dreams and Testimony

On May, 1917, a trembling and stammering Owen, diagnosed with shell shock, was admitted to Craiglockhart War Hospital under the care of Arthur Brock. In Sherston’s Progress (1936), Sassoon vividly remembers how at night the whole hospital reverted to the ‘underworld of dreams’ as each man relived his ‘submerged memories of warfare’.[13] It is deeply revealing that the ultimate testimony of the gas attack is placed not in the act of perception, but in the realm of the unconscious (‘in all my dreams’).

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

‘Guttering, choking, drowning’: the compulsive rhyme of the gerundive ‘-ing’ suggests the eternal now of the trauma victim who, as Freud noted in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), is forced to relive the past experience as perpetual present. As Owen shifts war trauma from the victim to the witness of the gas-attack, it gets laced with survivor guilt. The accusatory gesture (‘He plunges at me’) looks forward to the ‘pawing’ men in ‘Mental Cases’ while the dreamscape is reminiscent of ‘The Sentry’ – ‘Eyeballs, huge-bulged like squids’,/Watch my dreams still’ – showing how certain images were bound up in Owen’s experience and representation of war neurosis. However, as Dominic Hibberd has powerfully argued, the root of such visions go beyond war trauma to his pre-War adolescent nightmares revolving around guilt, sexual conflict and unresolved tensions.[14] Within the poem however, the above image bears witness to the process by which a dream image is transformed into one of the most powerful and poignant sense experiences: the image of the eyes writhing in the face embraces not only what has been witnessed but what has been begotten by the unconscious testimony of the dream. Such testimony is now set against the ‘desperate glory’ of war propaganda and Horace’s ‘old Lie’.

A hundred years on, ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ – somewhat like the Last Post – has moved, beyond literary history and cultural memory, into a structure of feeling in the English-speaking world. For some, it is their first encounter with poetry. We seldom read ‘Dulce’: it is usually a matter of re-reading, returning, remembering, with pain, pleasure, pity, even resistance. Poetry makes nothing happen, Auden famously noted, but its long-term political and affective power cannot be underestimated. The whole tradition of British anti-war poetry, built on poems such as ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’, may have played a part, as Jon Stallworthy reminds us, in the extraordinary protest marches in London against the Iraq war in 2003.[15] Combining realism, fantasy, j’accuse, protest and war-haunted testimony, it is also a poem par excellence as politics and aesthetics are yoked together through real-life violence.

脚注

- Wilfred Owen: Collected Letters, ed. by Harold Owen and John Bell (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. 499–500. Underlined in the original. Hereafter CL.

- CL, 81-82

- CL, p. 429. The two words are underlined in the original letter.

- All references to the poems are from Jon Stallworthy's two-volume edition The Complete Poems and Fragments of Wilfred Owen (London: Chatto and Windus, 1983, revised in 2013), 166, 165, 124, 169, 178, 140, 123. Hereafter abbreviated as CP&F.

- The italics are mine.

- W B Yeats, Oxford Book of Modern Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. xxxiv.

- 'Dulce Et Decorum Est', CP&F, 140. The different manuscript drafts are reproduced in Volume II, pp. 292–297.

- Stallworthy, Wilfred Owen (London: Chatto & Windus, 1974), p. 95.

- CL, p. 428.

- Owen to Colin Owen, CL, 14 May, 1917, p. 458.

- Sigmund Freud, ‘Infantile Sexuality’, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VII, translated by James Strachey (London: Hogarth, 1953), p. 203.

- CL, p. 500.

- Siegfried Sassoon, Sherston's Progress (1936; London: Faber, 1988), p. 51.

- Dominic Hibberd, Owen the Poet (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1986).

- Jon Stallworthy in 'War Poetry: A Conversation' in The Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War, edited by Santanu Das (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 266.

© Santanu Das

撰稿人: Santanu Das

Dr Santanu Das is the author of Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature (Cambridge, 2005) and the editor of Race, Empire and First World War Writing (Cambridge, 2011) and the Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War (2013). His book India, Empire and the First World War: Words, Images and Objects is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.