Jane Austen’s Juvenilia

出版日期: 1790-93 类型: Satire 创建: 1790-93

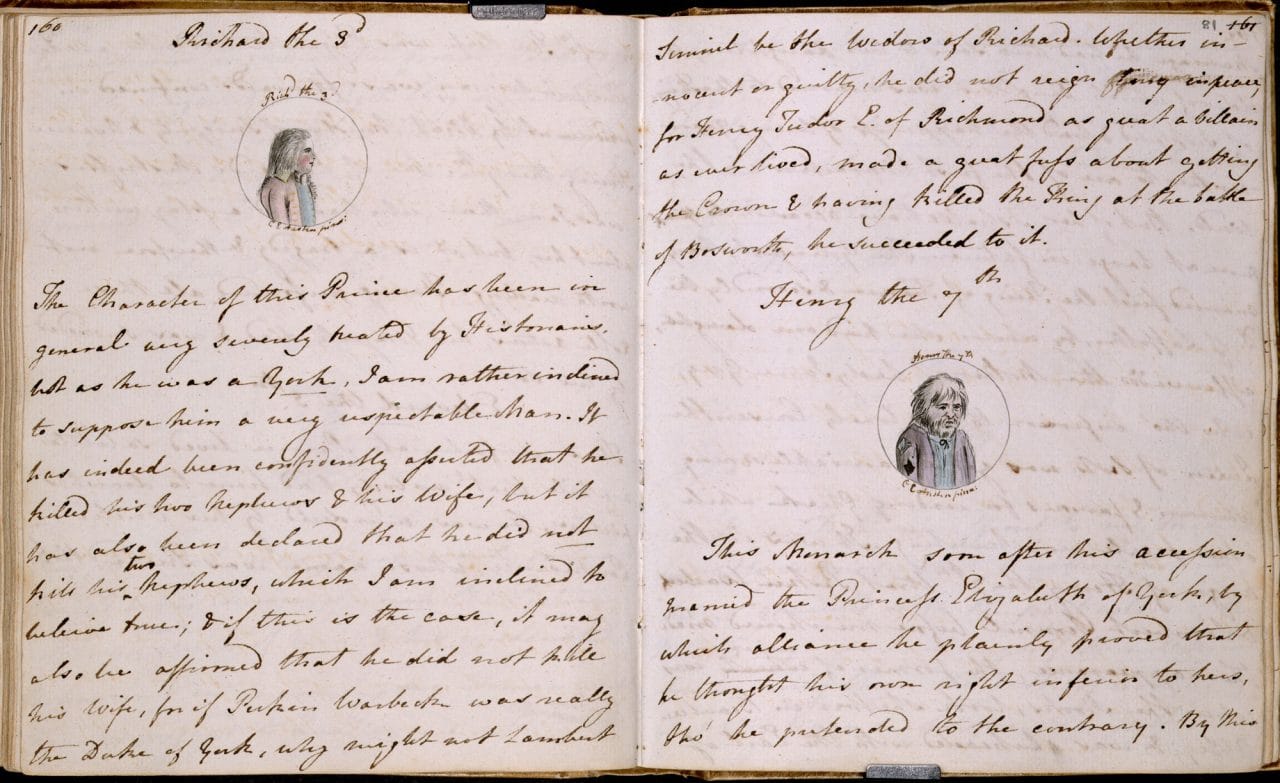

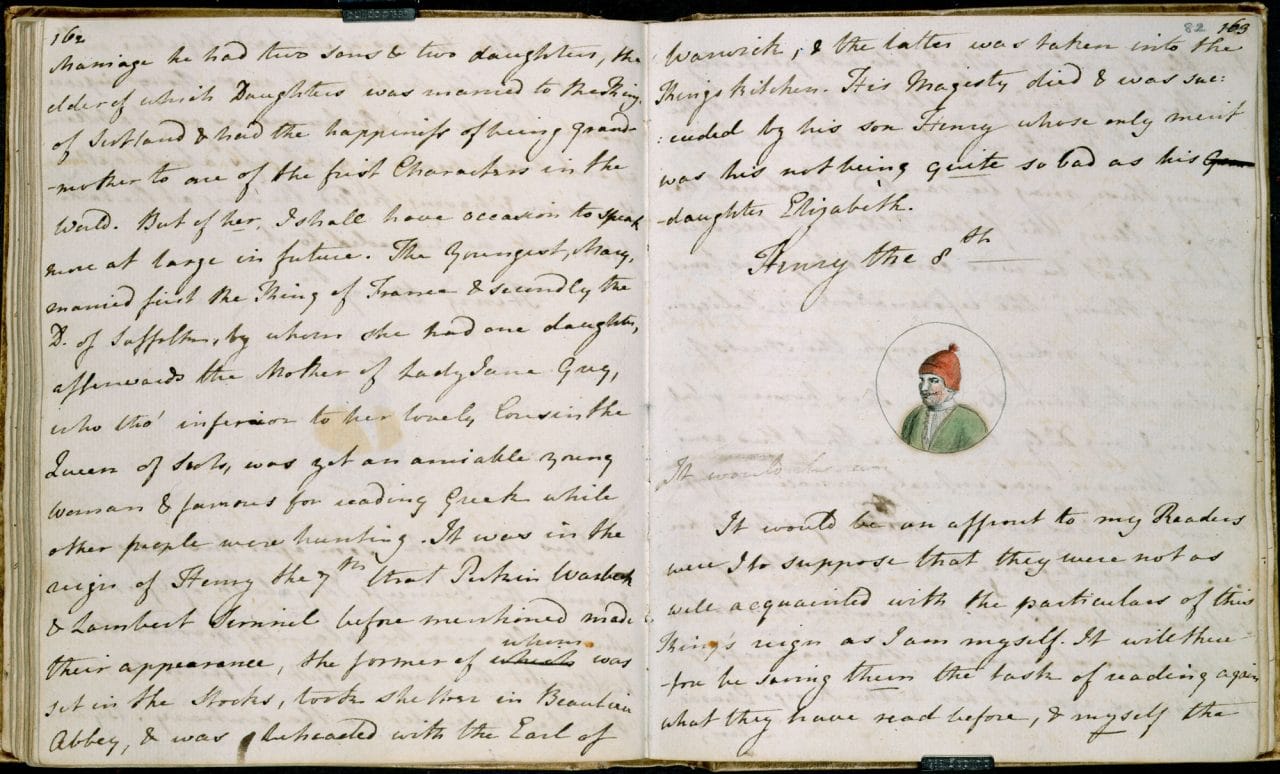

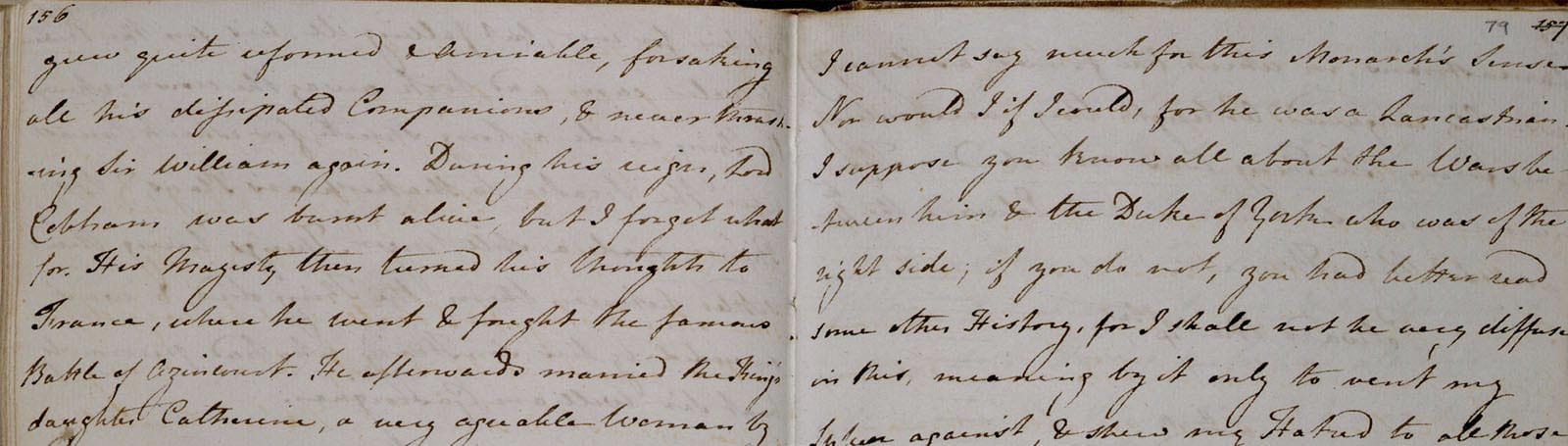

‘The History of England’, written when Austen was just 15 years old, is a parody of the standard schoolroom books of Austen’s time, in particular Oliver Goldsmith’s popular History of England from the Earliest Times to the Death of George II (1771). A note on the bottom of the first page marks out the tone of the tale: ‘N.B. There will be very few Dates in this history’. Declaring herself to be a ‘partial, prejudiced and ignorant Historian’, Austen cites works of fiction, such as Shakespeare’s plays, as historical authorities and includes references to her own family and friends. Jane’s older sister Cassandra illustrated the text with imaginative (and not always flattering) sketches of the English monarchs.

Jane Austen’s Juvenilia

Juvenilia are childhood writings, works produced by an author or an artist in their youth. Three of Jane Austen’s notebooks survive containing early short works in a variety of genres (stories, dramatic sketches, verses, moral fragments). They are inscribed on their front covers ‘Volume the First’, ‘Volume the Second’ and ‘Volume the Third’, consciously imitating the publishing format of 18th-century novels. The earliest pieces probably date from 1786 or 1787, around the time, aged 11 or 12, that Jane Austen left the Abbey House School in Reading. The latest dated entry is ‘June 3d 1793’, when she was 17. Two of the notebooks, ‘Volume the Second’ and ‘Volume the Third’, are among the treasures of the British Library; ‘Volume the First’ is held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

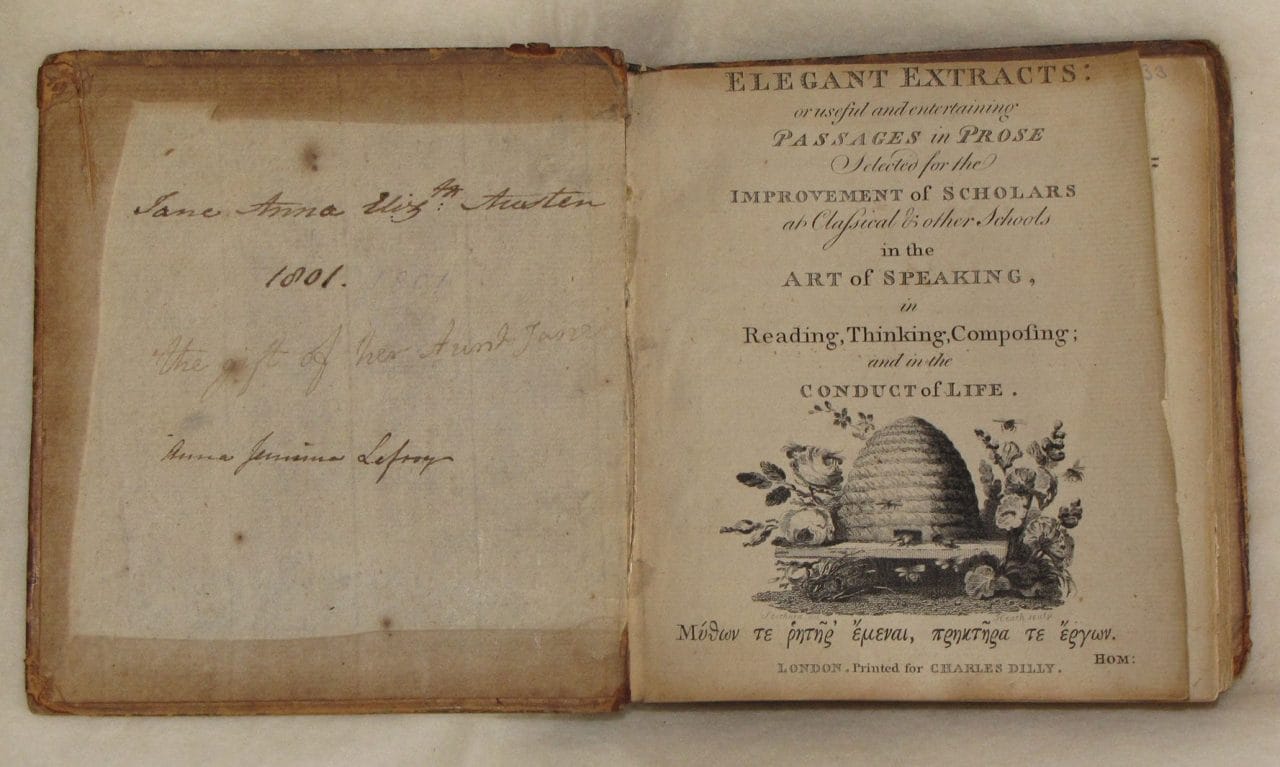

All three notebooks are confidential publications; that is, they are semi-public manuscripts intended for circulation and performance among family and friends. Unlike many teenage writings (then and now), these are not secret or agonised confessions entrusted to a private journal and for the writer’s eyes alone. Rather, they are stories to be shared and admired by an audience; most are accompanied by an elaborate dedication to a family member or friend, and they are filled with allusions to shared jokes and events. These are sociable texts, produced by a precocious young writer showing off her talents and expecting to be admired. All three notebooks exhibit evidence of heavy wear, which suggests they were frequently read and perhaps their mini-plays were acted. Later additions to ‘Volume the Third’, in the hands of Jane Austen’s nephew, James Edward Austen, and her niece, Jane Anna Elizabeth Lefroy, imply that the notebooks may have been used by the next generation to practise their writing skills.

What is the subject matter of the juvenilia?

Jane Austen’s earliest writings appear to have little in common with the restrained and realistic society portrayed in her adult novels. By contrast, they are exuberantly expressionistic tales of sexual misdemeanour, of female drunkenness and violence. They are characterised by exaggerated sentiment and absurd adventures. Running through them is a pronounced thread of comment on and wilful misreading of the literature of her day, showing how thoroughly and how early the activity of critical reading informed her character as a writer.

Jane Austen’s earliest writings are comic imitations or parodies of popular novels: of the classic Sir Charles Grandison by her favourite Samuel Richardson; of Oliver Goldsmith’s schoolroom textbook, The History of England (4 vols, 1771); of the essayists Joseph Addison and Samuel Johnson; and of the anthologies of moral pieces and ‘Elegant Extracts’ which formed the staple of young ladies’ education.

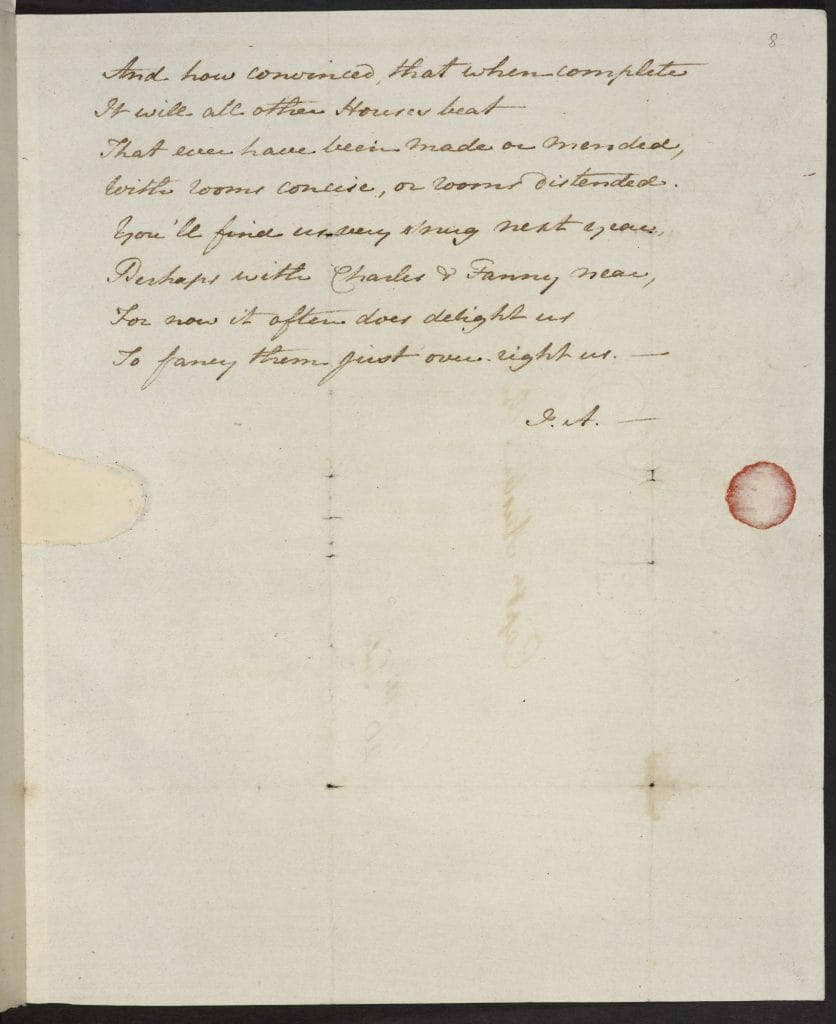

‘The History of England … By a partial, prejudiced, and ignorant Historian’ in ‘Volume the Second’ is a collaboration with her sister Cassandra who provided 13 coloured caricature portraits. The spoof history is consciously modelled on Goldsmith’s History, with its prefatory hope that ‘the reader will admit my impartiality’; Goldsmith too included medallion portraits of kings.

Common to all three notebooks is their portrayal of confident, wilful, even rebellious young women: heroines such as Charlotte Lutterell of ‘Lesley Castle’ (‘Volume the Second’) and Catherine or Kitty, as she is usually styled, in the longer ‘Kitty, or the Bower’ in ‘Volume the Third’. Kitty is a more naturalistic figure than the farcical adventurers of the earlier tales but, like them, she is independent and outspoken.

How is the juvenilia reflected in Austen’s novels?

Jane Austen did not simply outgrow her juvenile notebooks. There is ample evidence that the same critical intelligence that created these satirical depictions of the conventions and stereotypes of late 18th-century fiction, conduct books and stage farces, continued to work within the more realistic framework of her mature novels. First drafts of books eventually published as Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey were written soon after the last of the juvenilia. It is not too fanciful to find traces of the strong-minded heroines of these early experiments in Elizabeth Bennet’s unladylike energy (‘crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles’, Pride and Prejudice, ch. 7) and Emma Woodhouse’s dangerously undisciplined imagination

Background

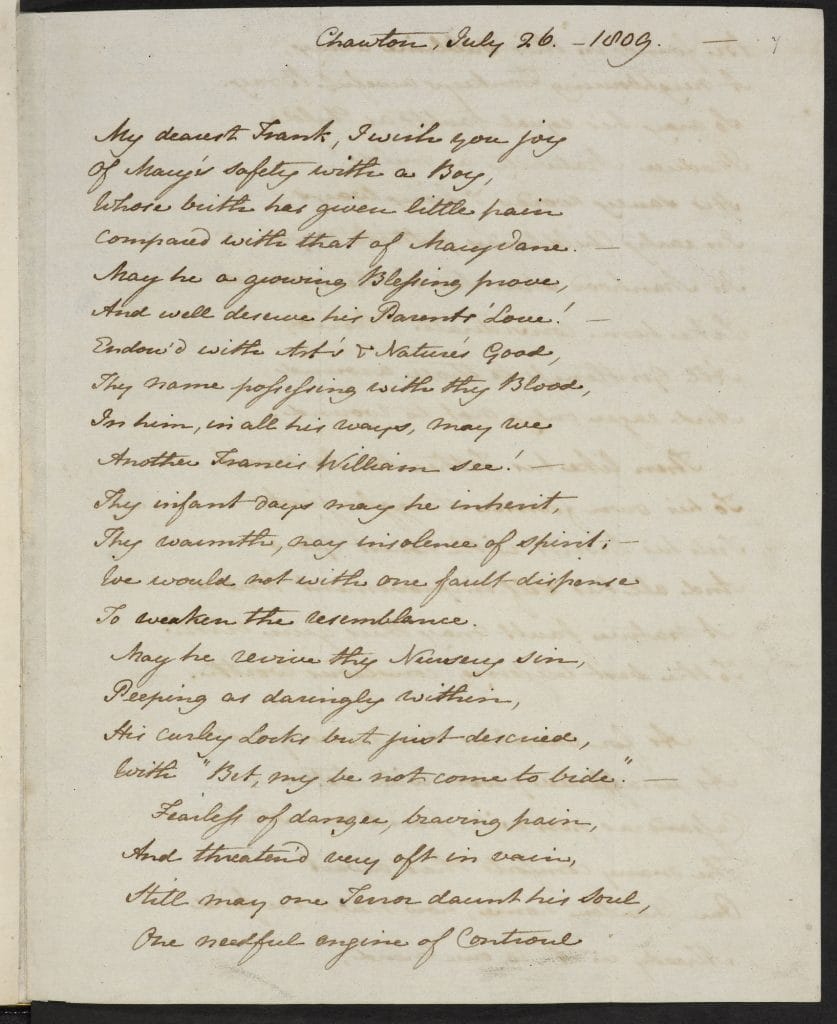

Jane Austen was born into a family of talented amateur writers. Her mother wrote playful verses, riddles and charades; her elder brothers James and Henry jointly founded and largely wrote a humorous weekly paper, The Loiterer, while students at St John’s College, Oxford. The paper ran for 60 numbers from January 1789 to March 1790 and was issued commercially, though its circulation was small. There were plenty of models for it among popular 18th-century periodicals, such as Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s Spectator (first series 1711–12) and Henry Mackenzie’s The Mirror (1779–80) and The Lounger (1785–87). Such papers were conversations in print, partly simulated and partly genuine interactions between writers and readers. James Austen also wrote poetry, and during the 1780s he devised new prologues and epilogues for the plays staged by the Austen children at amateur family theatricals. James and Henry Austen undoubtedly influenced Jane Austen’s teenage compositions.

Written by: Kathryn Sutherland.

Kathryn Sutherland is a Professorial Fellow in English at St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford. Her research interests include writings from the romantic period, Scottish Enlightenment, textual theory and Jane Austen. She is currently directing an AHRC research project: Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition and Print Edition (to be published by Oxford University Press).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.