Female education, reading and Jane Austen

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw fierce debates about the nature and purpose of women’s education. Professor Kathryn Sutherland assesses these debates and describes the education and reading practices of Jane Austen and her female characters.

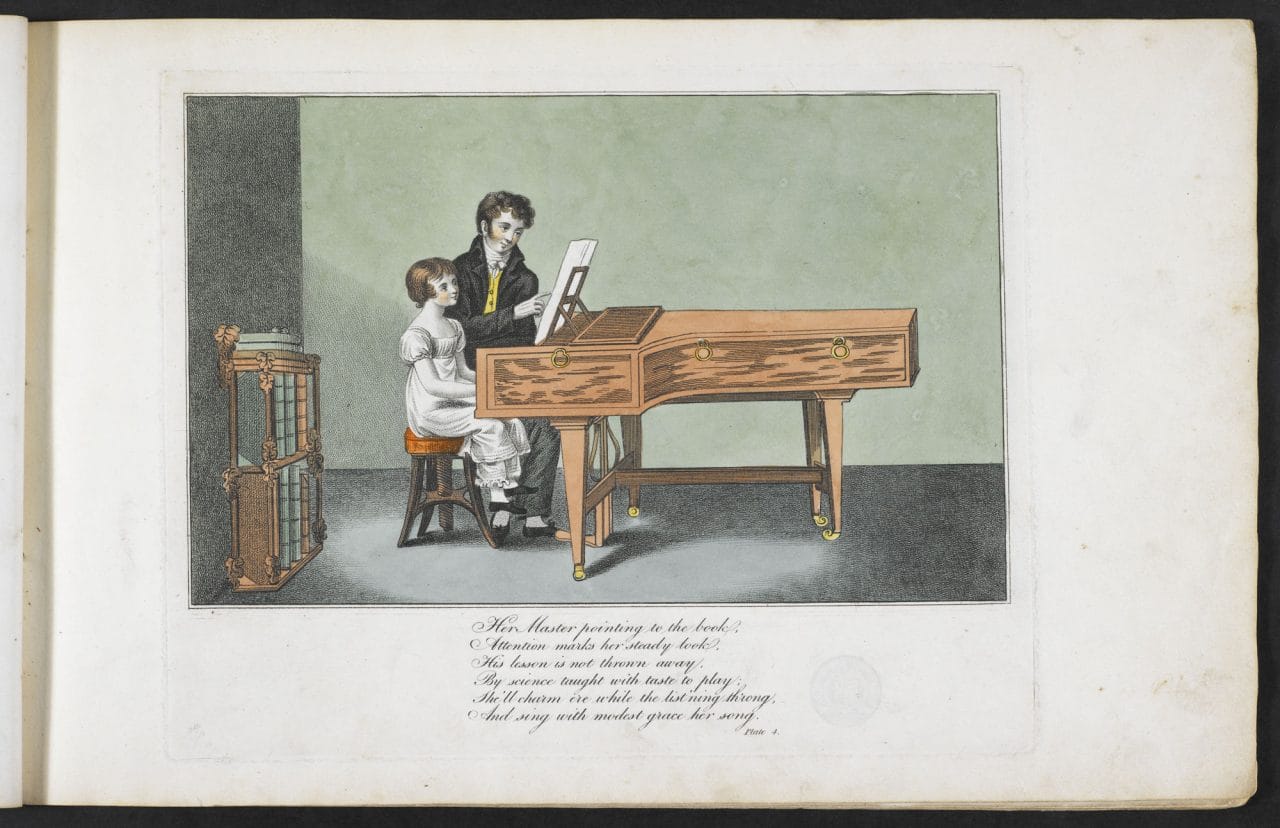

Jane Austen and her elder sister Cassandra both attended schools: briefly in Oxford and Southampton in 1783; for a slightly longer period the Abbey House, Reading, a boarding school for daughters of the clergy and minor gentry, in 1785-6, when Jane was 10. But most of their education was undertaken privately at home, where their father, Reverend George Austen, supplemented his clerical income by taking boy pupils as boarders. It is likely that the Austen sisters benefited from their father’s library and from his informal instruction. We do not know whether or not they also sat in on any of the boys’ classes. At the Abbey House the curriculum included writing, spelling, French, history, geography, needlework, drawing, music and dancing. While two of her brothers would go on to take degrees at Oxford University and another would complete his education with a four-year Grand Tour of Europe,Jane Austen and her sister, like all other women of the time, even those of their social background (the gentry and upper middle classes), had little formal education, no admittance to university or to a career, and no opportunity for independent travel.

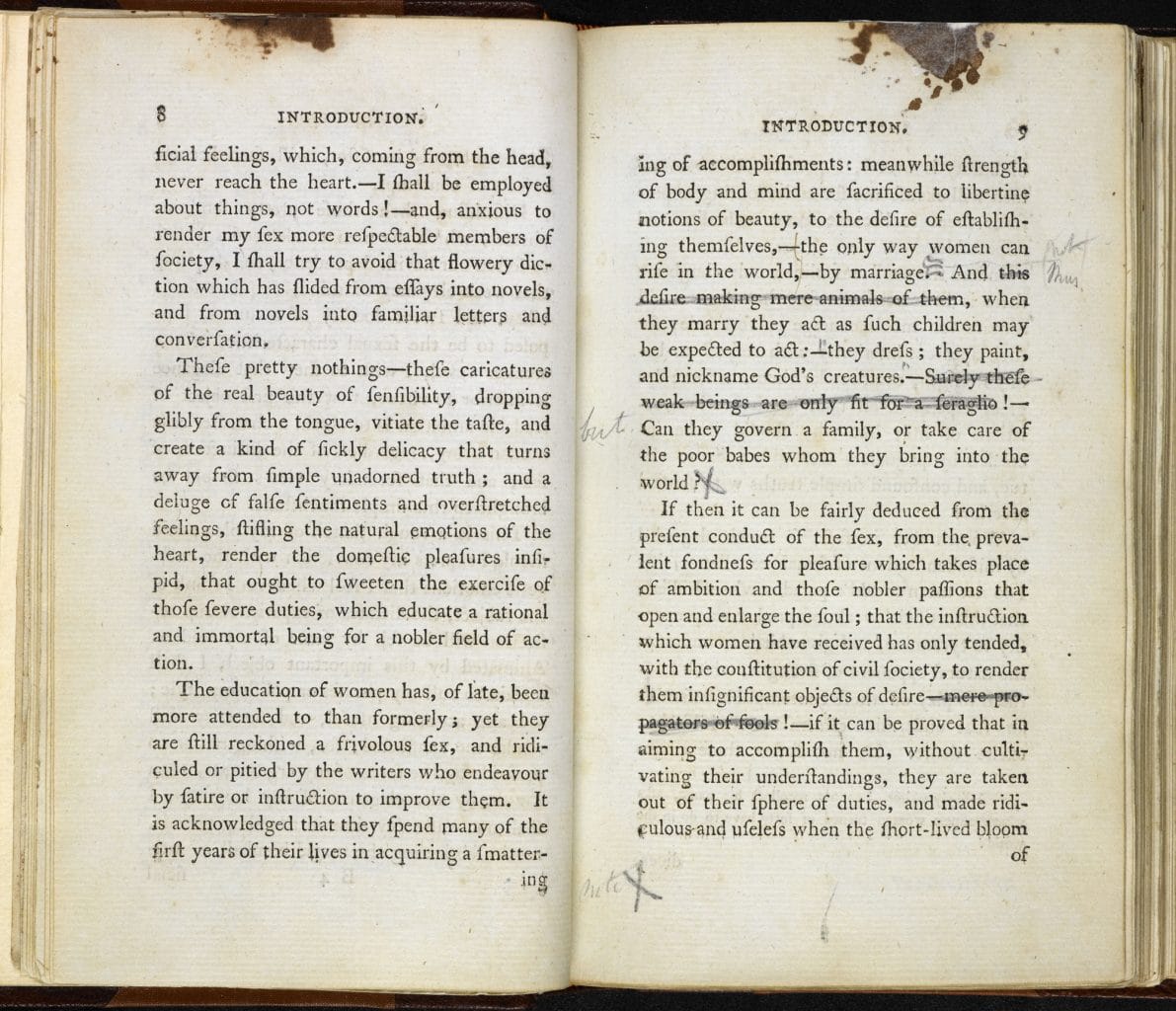

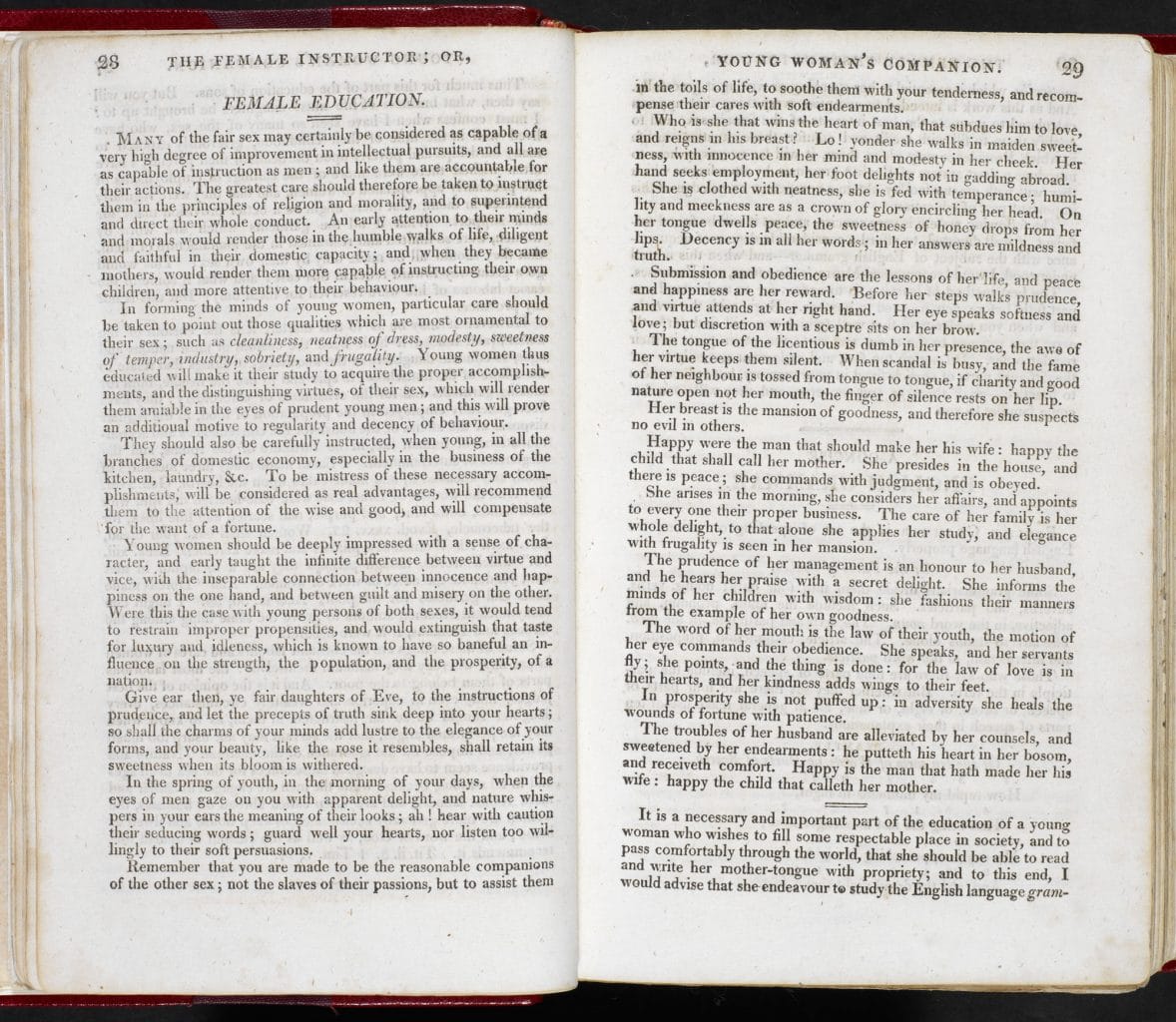

Condemning the limits of women’s education

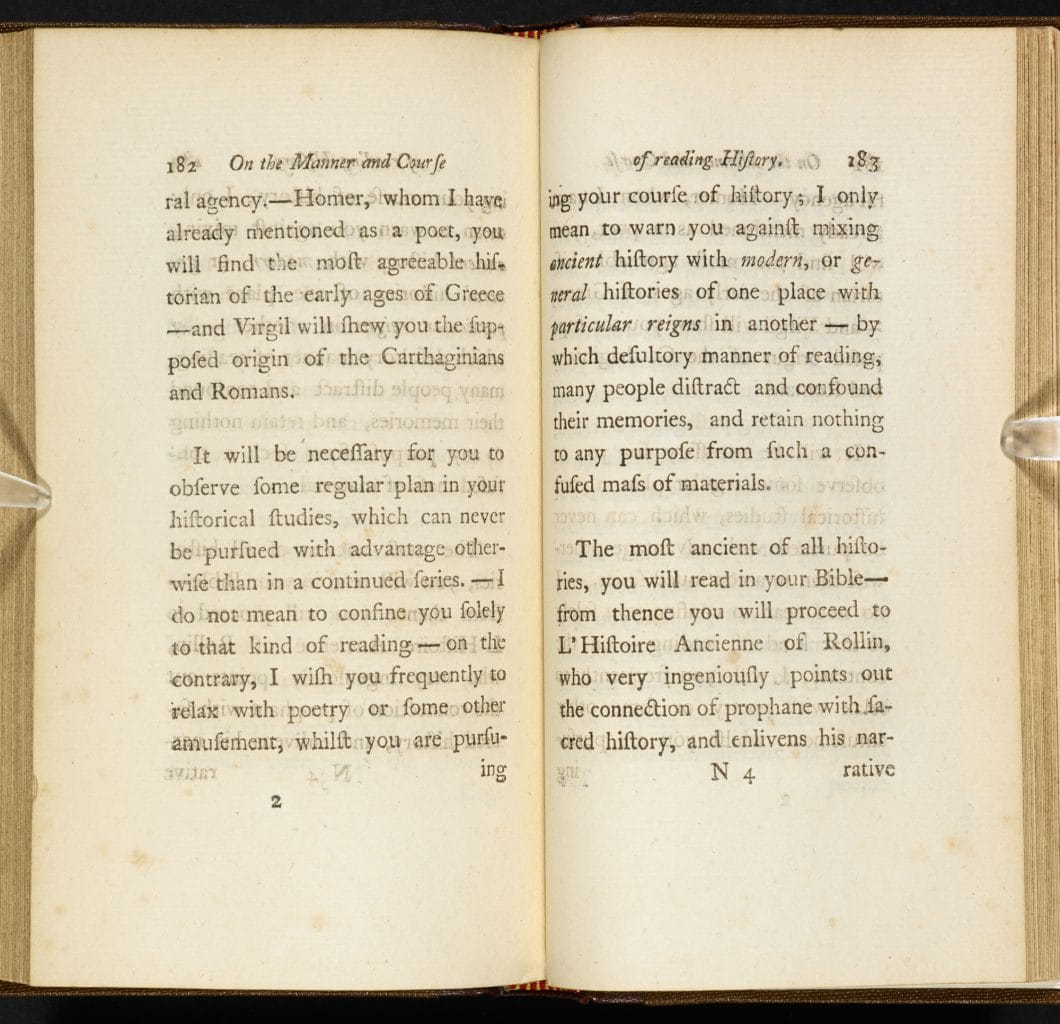

During Jane Austen’s lifetime the limited nature of women’s opportunities to learn was the subject of lively debate among female educationalists. Writers with otherwise opposing political views, like Catharine Macaulay, Mary Wollstonecraft, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Hester Chapone and Hannah More, were united in their condemnation of the narrow limits of female education. In Letters on Education (1790), the radical Macaulay advised parents, ‘Confine not the education of your daughters to what is regarded as the ornamental parts of it’. By ‘ornamental parts’ she meant drawing, music, a smattering of French and Italian, just enough to attract a husband, but not intimidate him and to offer some refuge from boredom in leisure hours. But equally, the more conservative Chapone argued for a disciplined and regulated course of reading that went deeper than mere fashion and accomplishment, writing: ‘The principal study, I would recommend, is history. I know of nothing equally proper to entertain and improve at the same time, or that is so likely to form and strengthen your judgment’. [1]

Jane Austen’s education

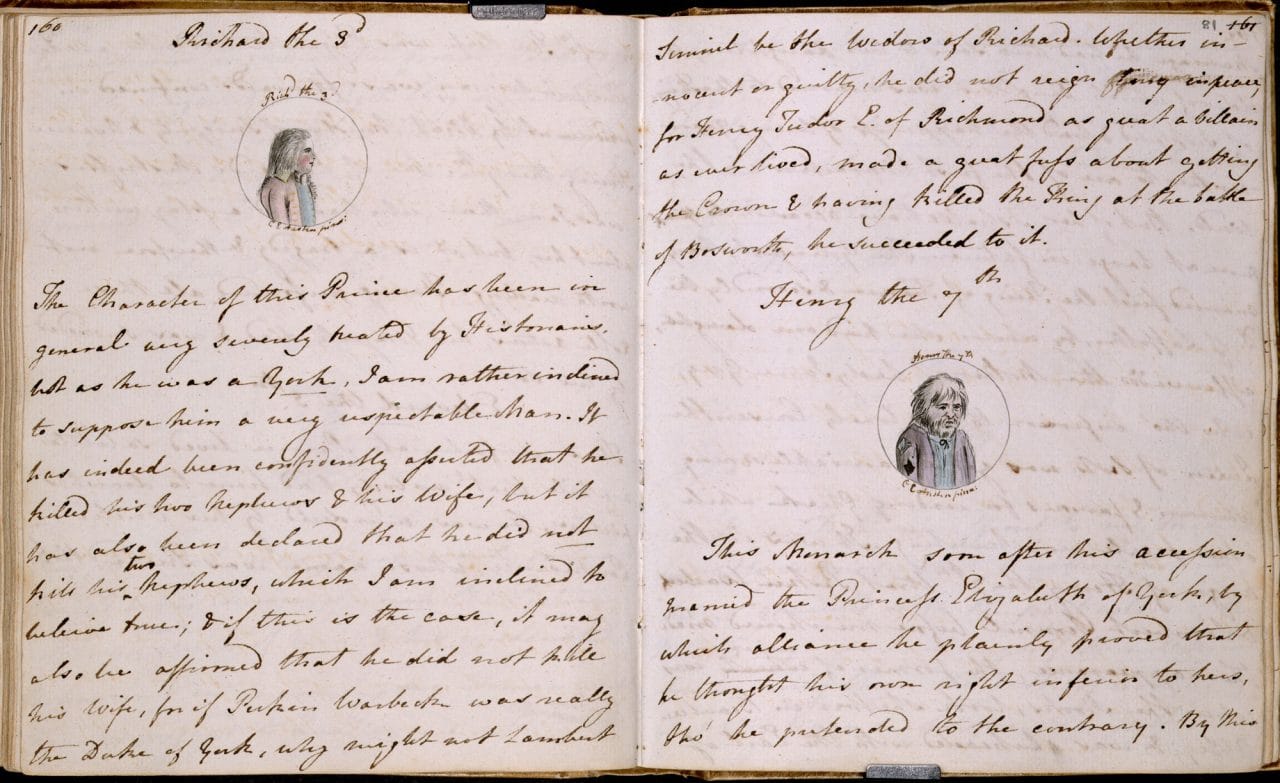

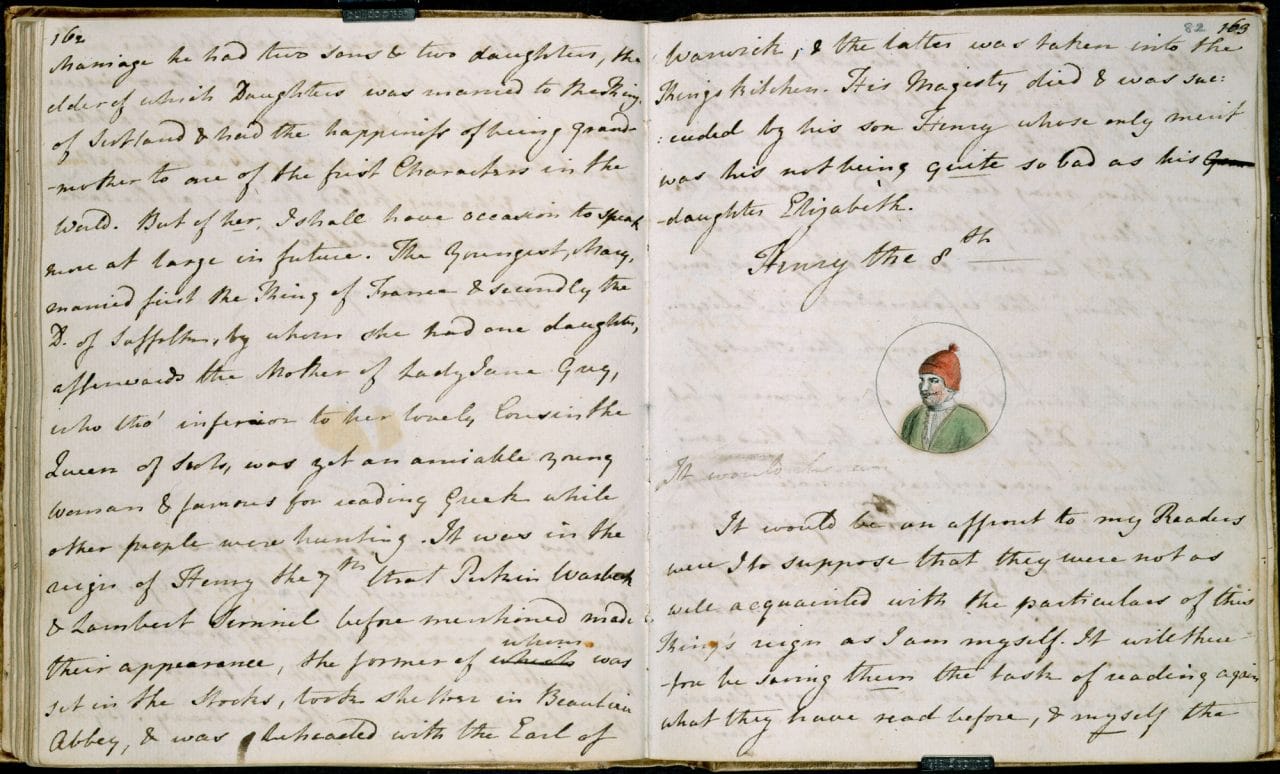

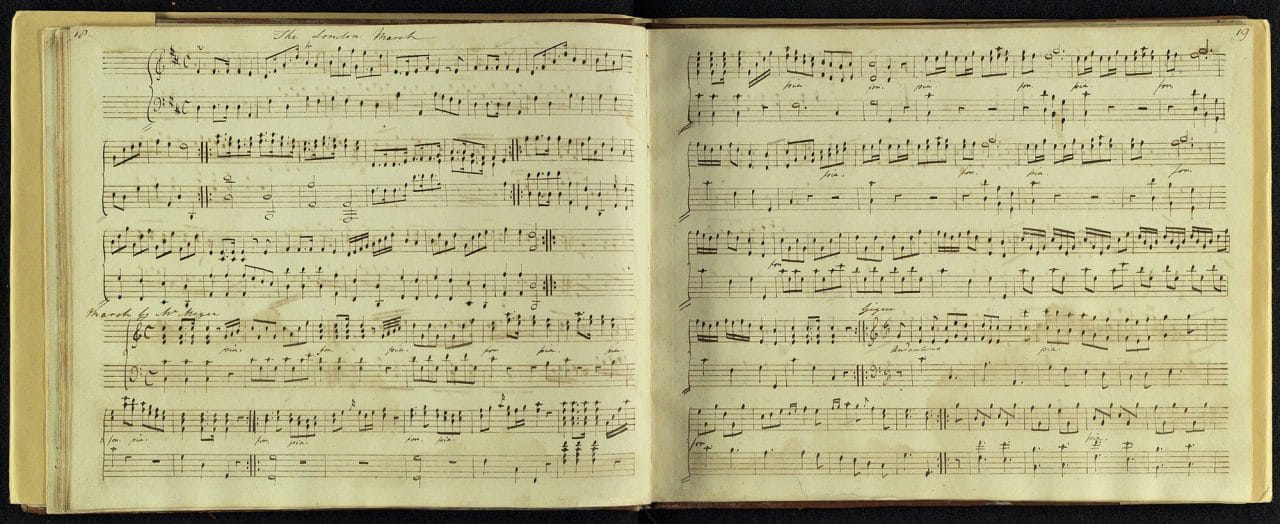

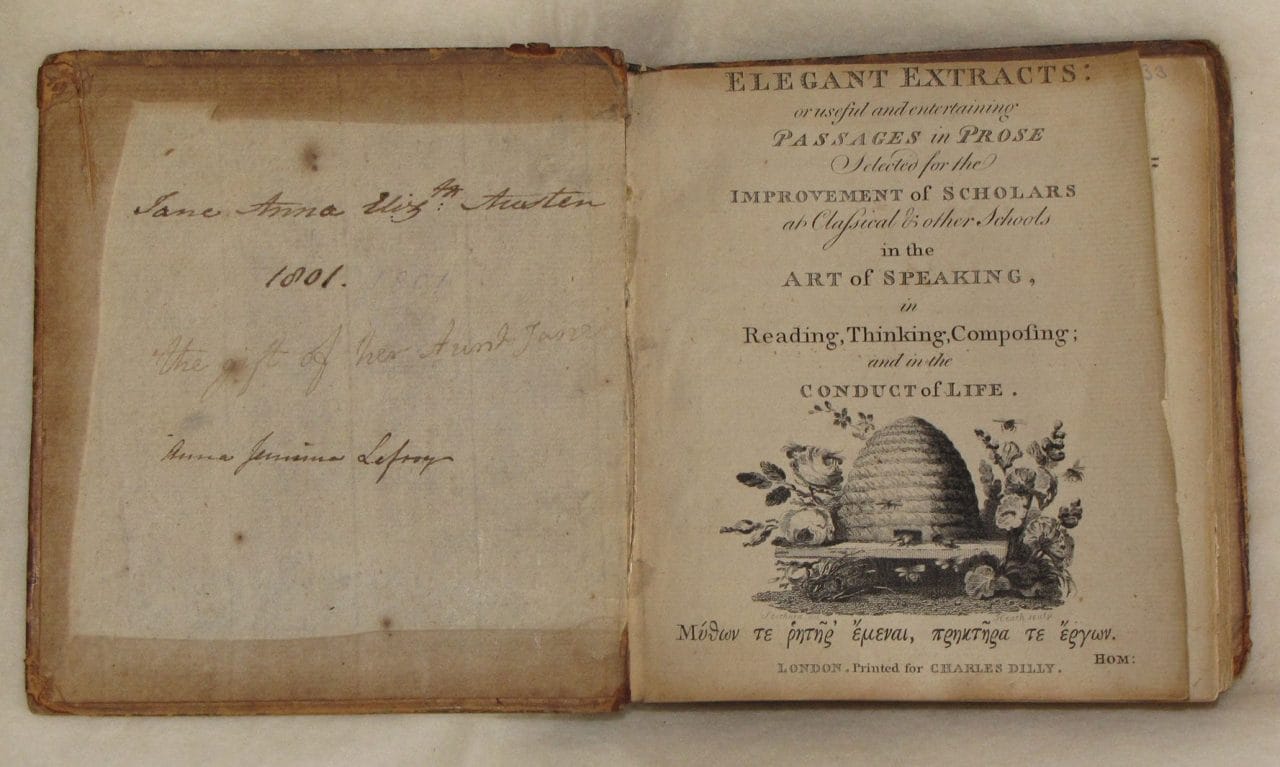

Several music books containing selections from a range of 18th-century composers copied out in Jane Austen’s hand survive to show she was a good amateur pianist. All her heroines have an appreciation of music, though some have more skill in playing than others. We know something, too, of her reading from books that include marginal comments in her handwriting: Goldsmith’s popular schoolroom textbook, The History of England (4 vols, 1771); Elegant Extracts: or useful and entertaining Passages in Prose Selected for the Improvement of Scholars at Classical & other Schools (London, no date), an anthology also much in use in late 18th-century schoolrooms. Austen’s copy was handed down through the family, inscribed ‘Jane Anna Elizth Austen 1801’, ‘the gift of her Aunt Jane’.

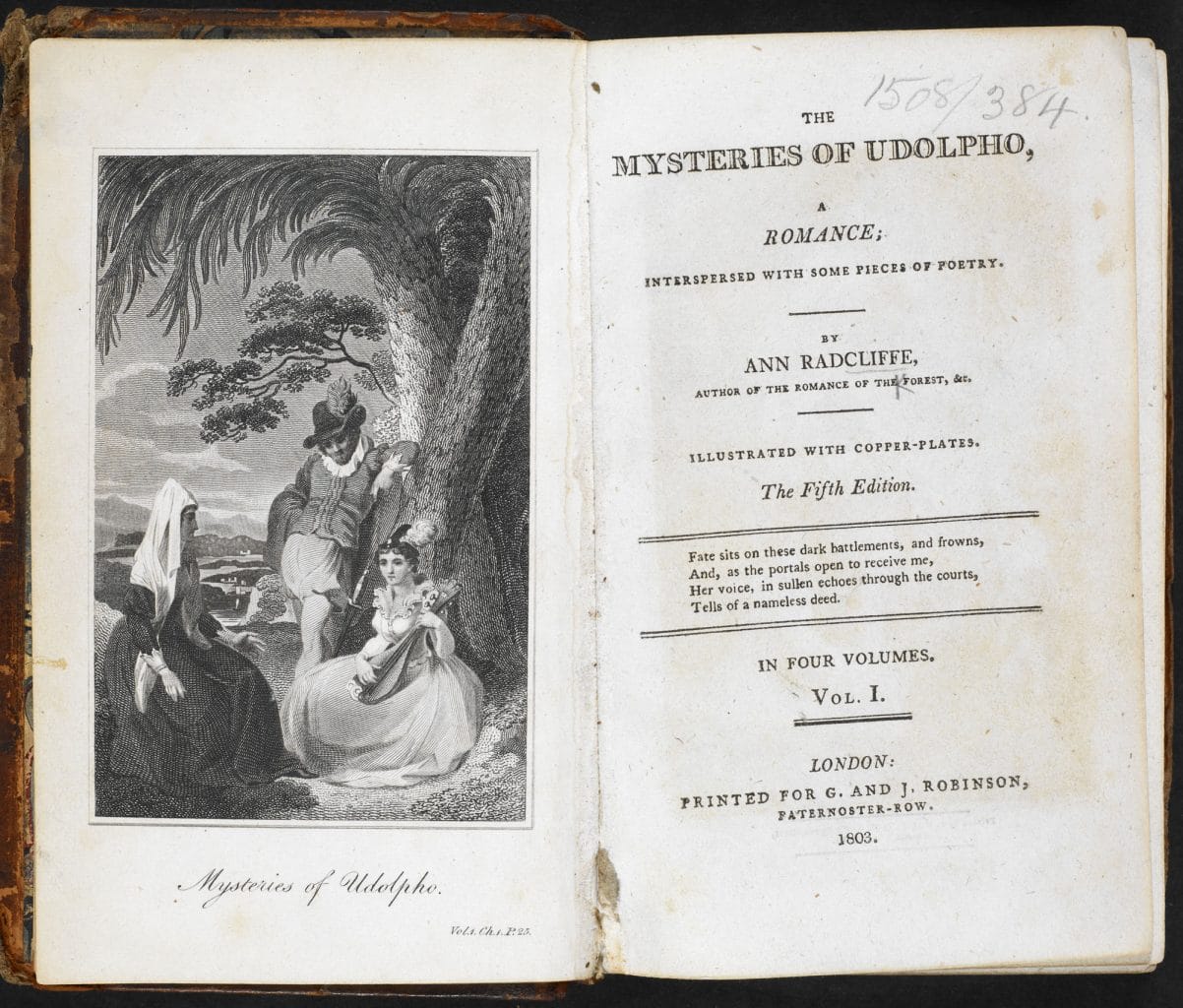

Austen knew a little Italian, and her childhood library contained La Fontaine’s Fables choisies in French, the gift of her French-speaking cousin Eliza. In an age when writing for children was itself in infancy, the young Jane Austen was undoubtedly a precocious reader, but she was no snob: she devoured junk and high-end literature alike. We know she read modern classics like the multi-volume novels of Samuel Richardson (Sir Charles Grandison was a special favourite) and the latest pulp fiction – extravagant and improbable tales of gothic terror and sentimental romances.

Attitudes to reading in Austen’s novels

All Jane Austen’s novels engage with the debate over women’s education by exploring the intellectual and moral distance between the show of mere accomplishments and the deeper understanding that signals self-knowledge. Often the distance between show and substance is what separates her heroines from other women in their society. For Austen one route to such inward knowledge is reading. At the same time, all her heroines are keenly aware of their deficiencies in education. Questioned by the insufferably rude Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Elizabeth Bennet admits to having few accomplishments: she cannot draw and plays the piano only ‘a little’; but rather than feeling her education ‘neglected’, she counters that ‘We were always encouraged to read’ (Pride and Prejudice, ch. 29). By contrast, Emma Woodhouse has grown up indulged by her governess and in consequence has picked up little real schooling. As early as Chapter 5 Mr Knightley points to her failure to submit to a serious plan of reading as a major fault in her development, saying ‘She will never submit to any thing requiring industry and patience, and a subjection of the fancy to the understanding.’ Of Austen’s women Anne Elliot, at 27 her oldest heroine, is most self-disciplined; she is also her most discriminating reader, advising the overwrought Captain Benwick to vary his diet of poetry with ‘such works of our best moralists … as occurred to her … as calculated to rouse and fortify the mind by the highest precepts’ (Persuasion, ch. 11). We sense that she is speaking with the authority of experience.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Kathryn Sutherland

Kathryn Sutherland is a Professorial Fellow in English at St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford. Her research interests include writings from the romantic period, Scottish Enlightenment, textual theory and Jane Austen. She is currently directing an AHRC research project: Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition and Print Edition (to be published by Oxford University Press).