Jane Austen: social realism and the novel

Jane Austen fills her novels with ordinary people, places and events, in stark contrast to other novels of the time. Professor Kathryn Sutherland considers the function of social realism in Austen’s work.

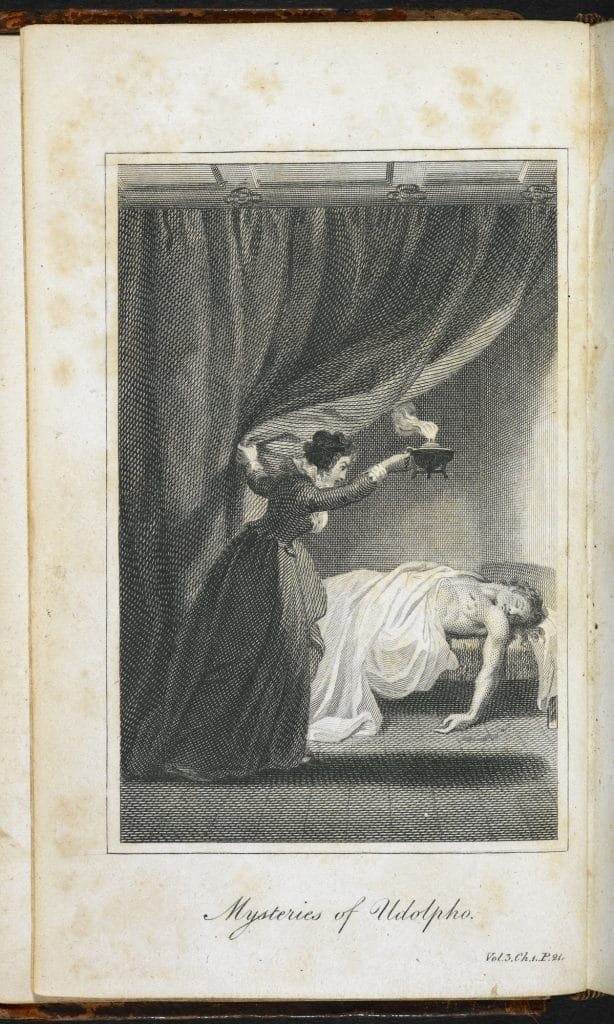

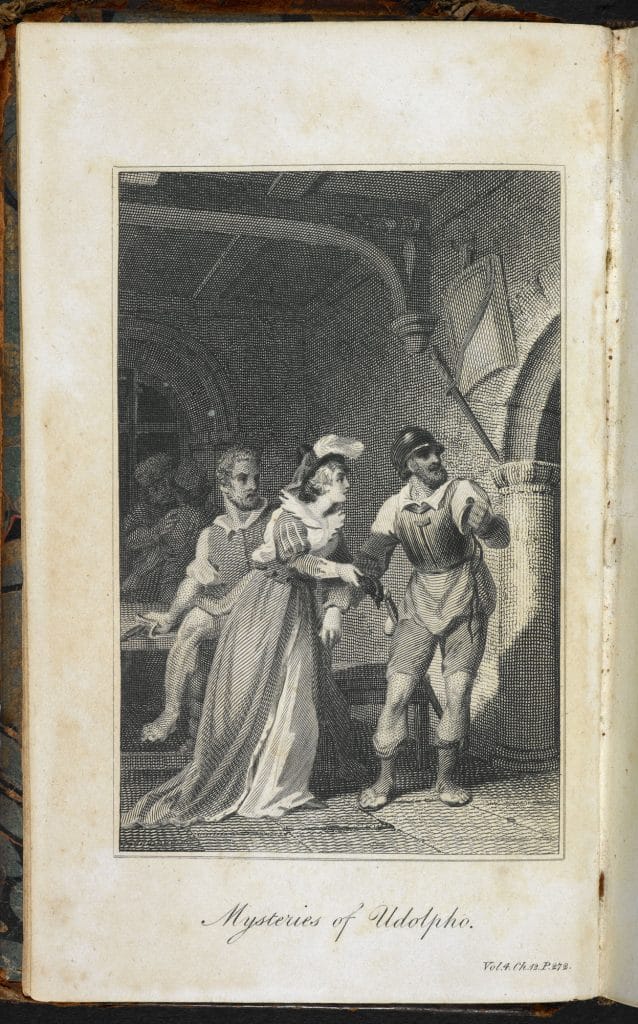

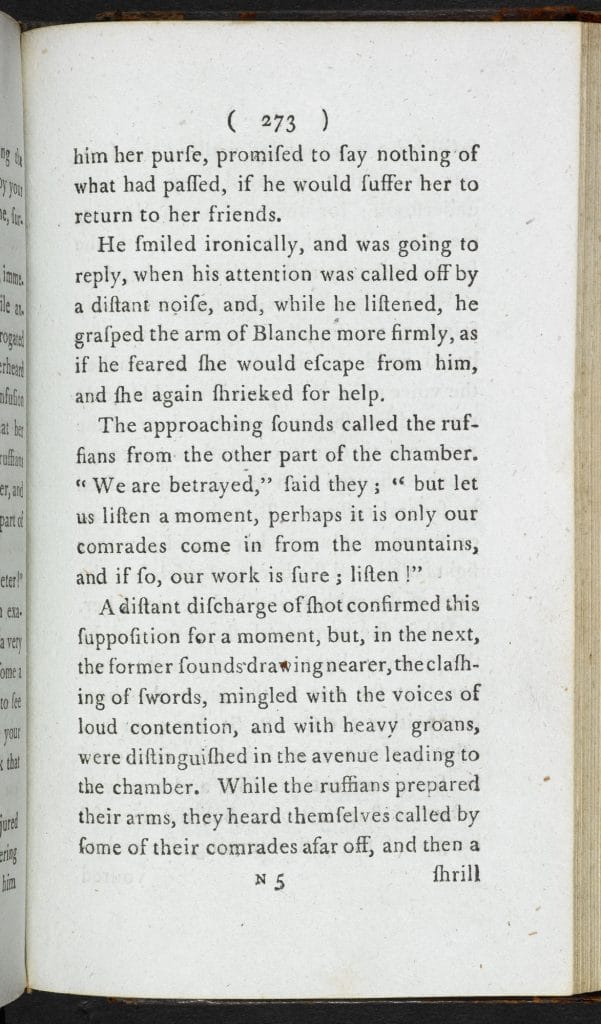

Jane Austen lived at a time when novel reading had become one of the major forms of entertainment for the middle classes. New works were prohibitively expensive to buy, but there were various methods of sharing and borrowing the latest fiction through circulating libraries, subscriptions libraries and reading clubs. Though widely read, the novel’s status was not high. Fiction poured from the printing presses, tales of adventure, mystery and intrigue with improbable settings and clumsy plots that lurched from one sensational incident to another. They often had bizarre titles, like Anna: or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress: interspersed with Anecdotes of a Nabob (1785), by Anna Maria Bennett, of which one contemporary reviewer wrote: ‘In some parts of it the incidents are scarcely within the verge of probability; and the language is generally incorrect’. Ann Radcliffe’s popular ‘Gothic’ fictions, enjoyed by Catherine Morland and Isabella Thorpe in Northanger Abbey, and Harriet Smith in Emma, occupied the high end of the market. In The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), Radcliffe’s heroine, the sensitive and romantically named Emily St Aubert, is imprisoned by her wicked uncle in an Italian castle where she undergoes numerous terrors before she eventually escapes.

Reacting against extravagance and sensation

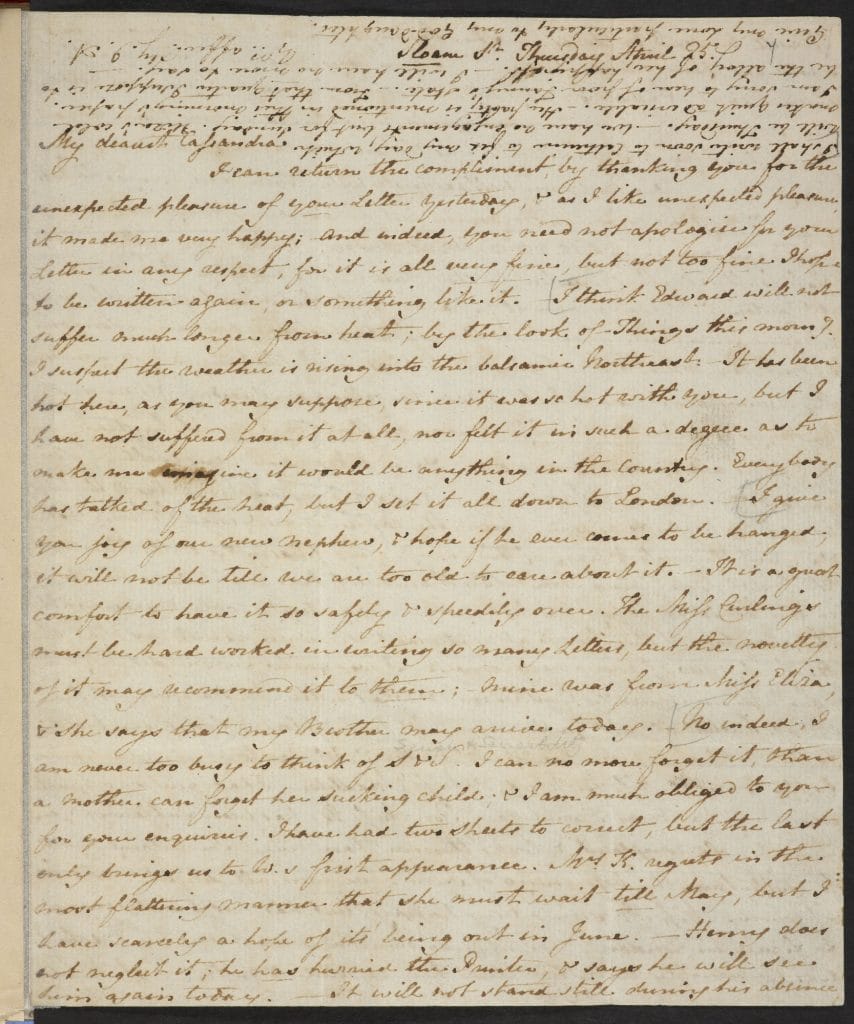

Jane Austen avidly devoured this pulp fiction, but she also reacted critically to it in writing her own novels. Her spoof Plan of a Novel, according to hints from various quarters, written in 1815-1816 around the time of the publication of Emma, mocks its extravagance. The Plan (a recipe for how not to write a novel) has several specific targets among the day’s bestsellers. Of these, Mary Brunton’s Self-Control (1810) is the most interesting because it is a novel that Austen refers to in several of her letters as the kind of work against which her own novels are written (see, for example, her letter to Anna Lefroy, 24 November 1814). In Self-Control the heroine Laura Montreville (note again the romantic, non-English sounding name, so different from those of Austen’s heroines) suffers dreadful experiences in her attempts to elude the lecherous villain Colonel Hargrave. She travels from Scotland to London, is kidnapped, endures a perilous sea crossing to Canada, and eventually escapes by canoe from a band of American Indians.

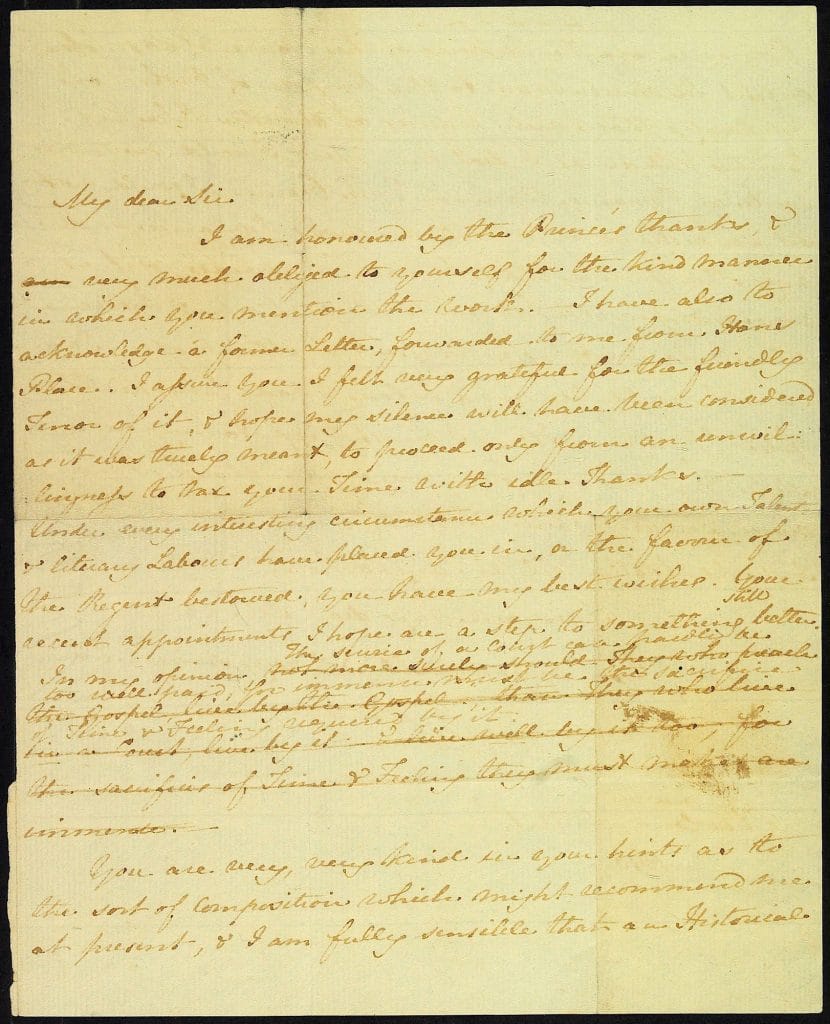

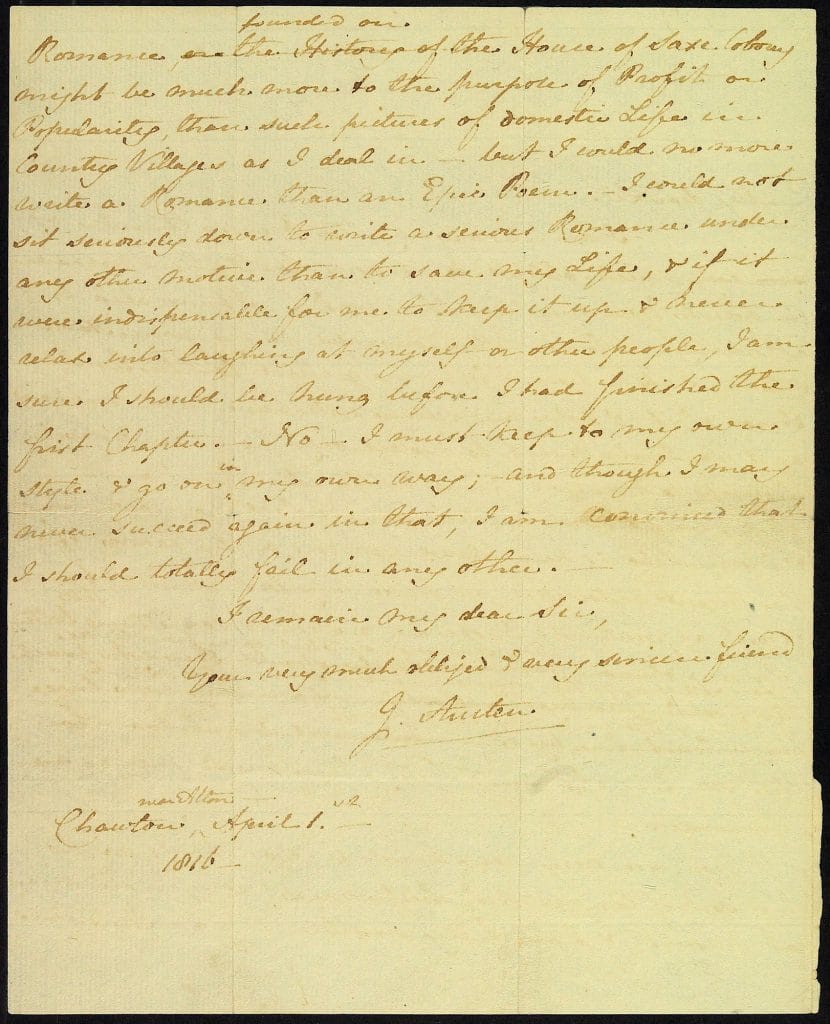

Jane Austen commented specifically on her own novels in relation to this kind of extravagantly romantic writing that,

I could not sit seriously down to write a serious Romance under any other motive than to save my Life, & if it were indispensable for me to keep it up & never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first Chapter. – No – I must keep to my own style & go on in my own Way; And though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other (1 April 1816, to James Stanier Clarke, an enthusiastic admirer of romances).

Describing ordinary life

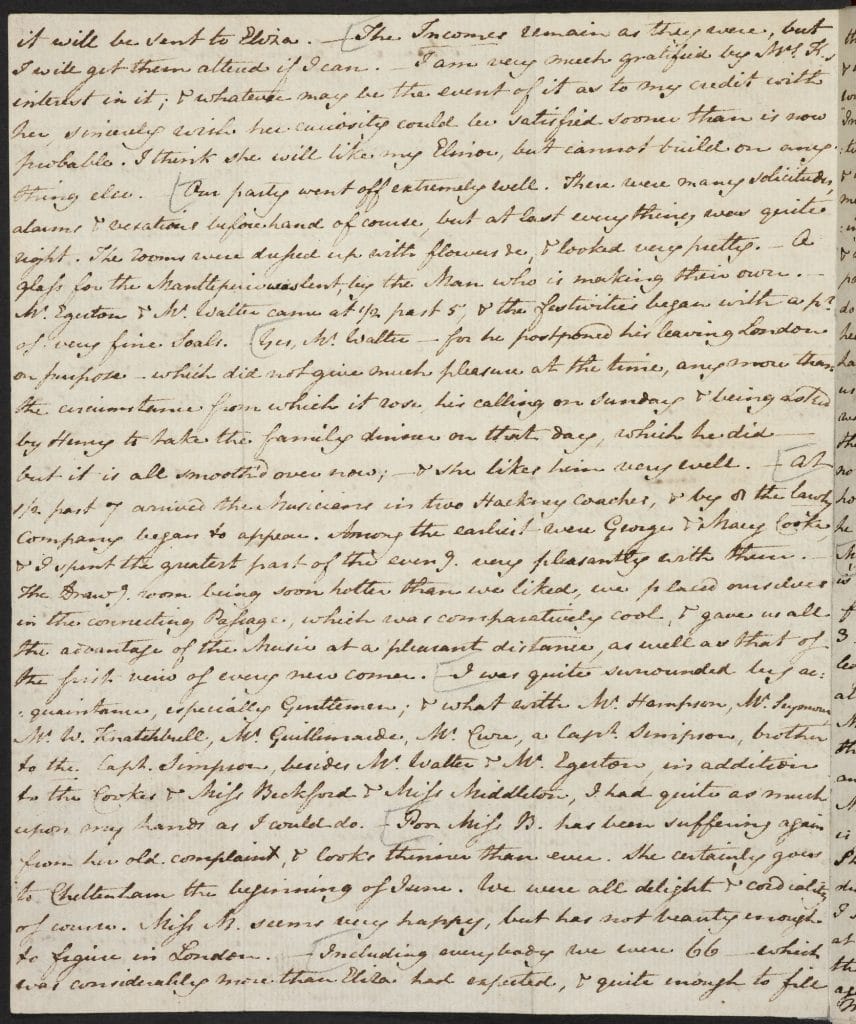

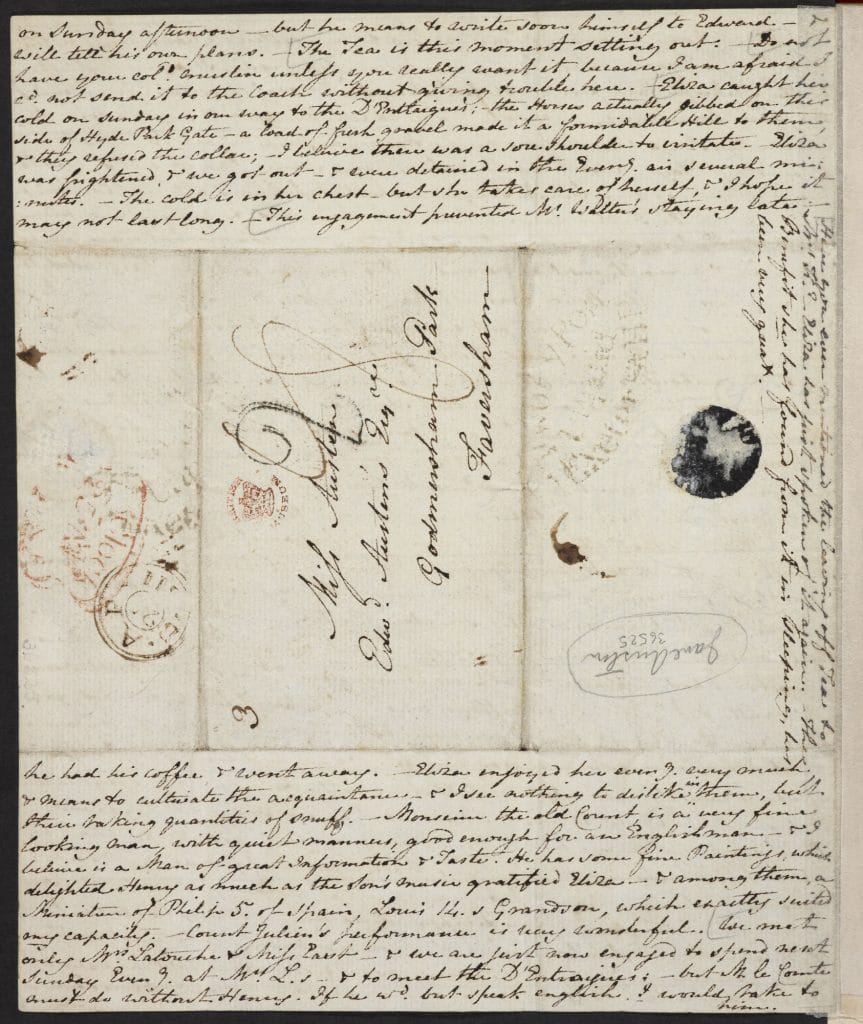

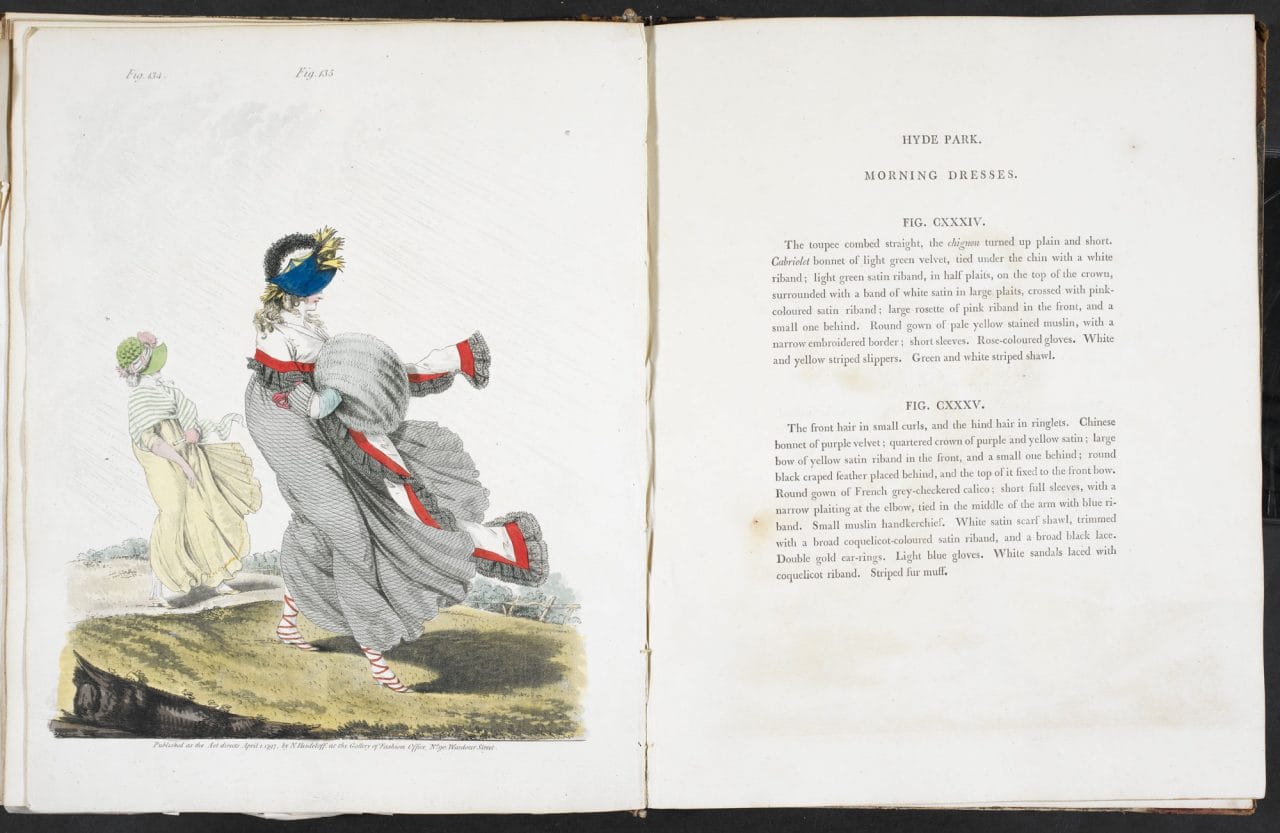

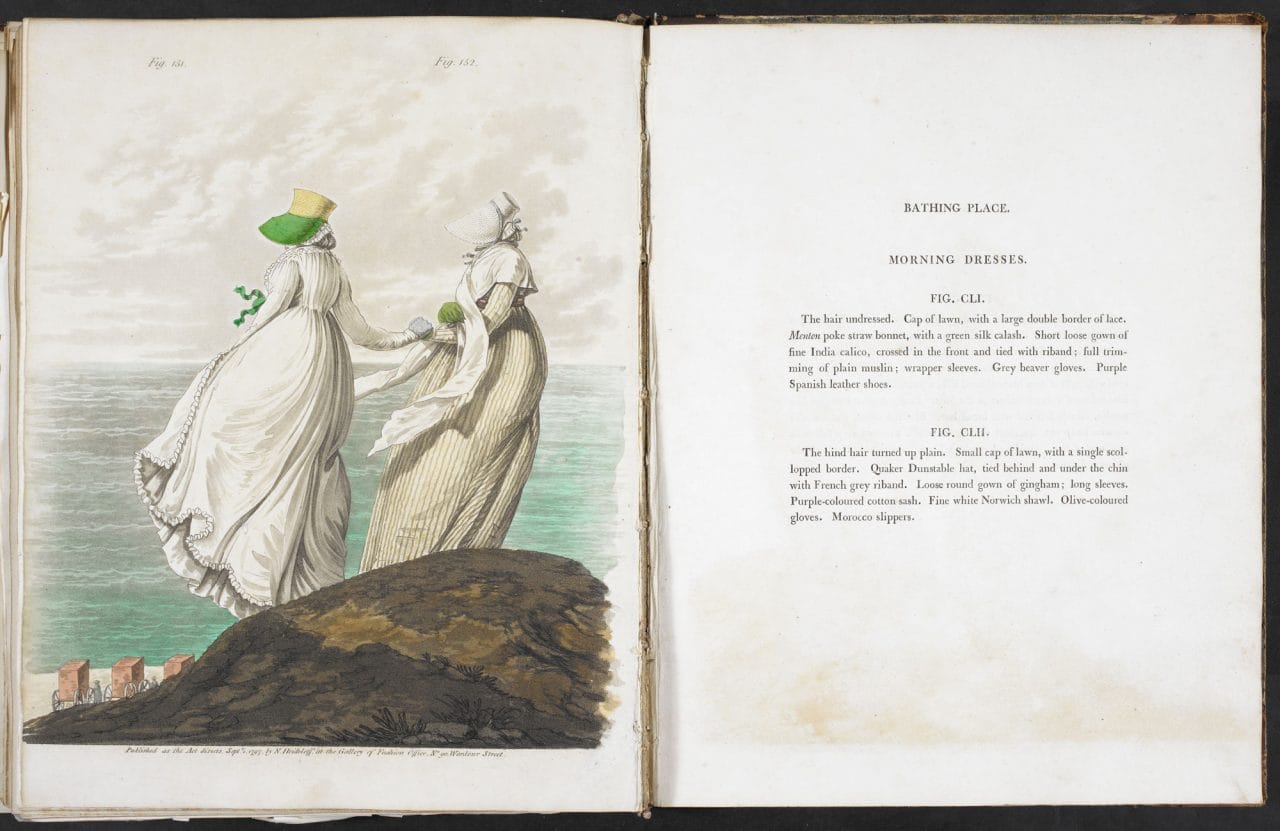

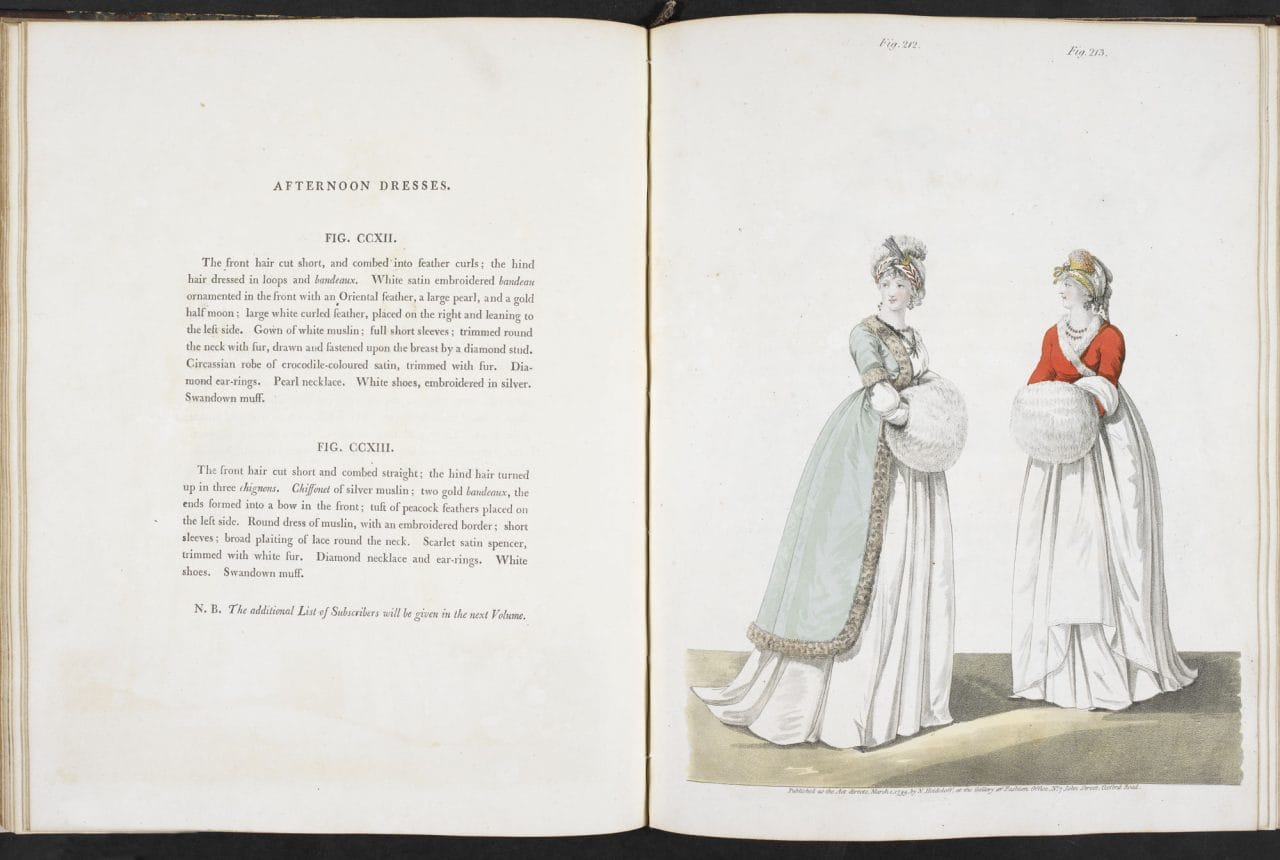

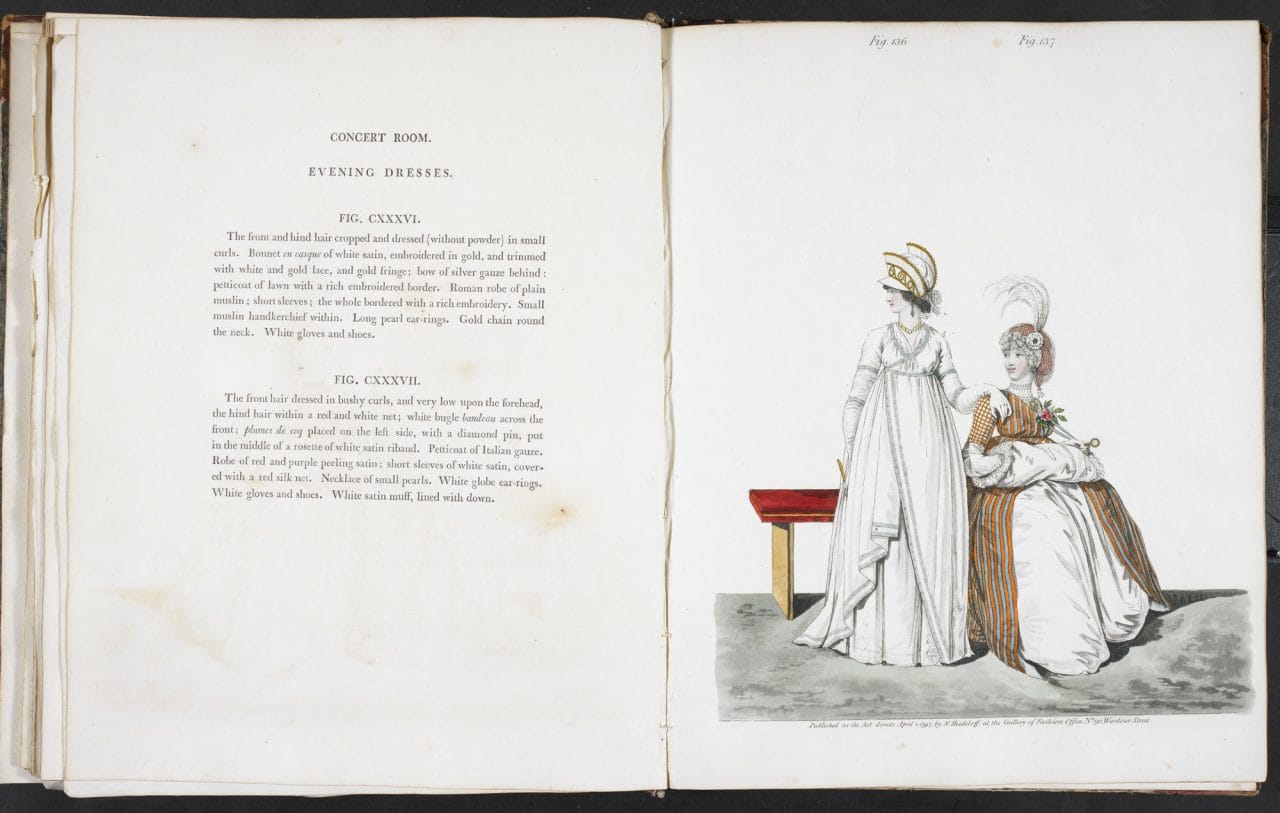

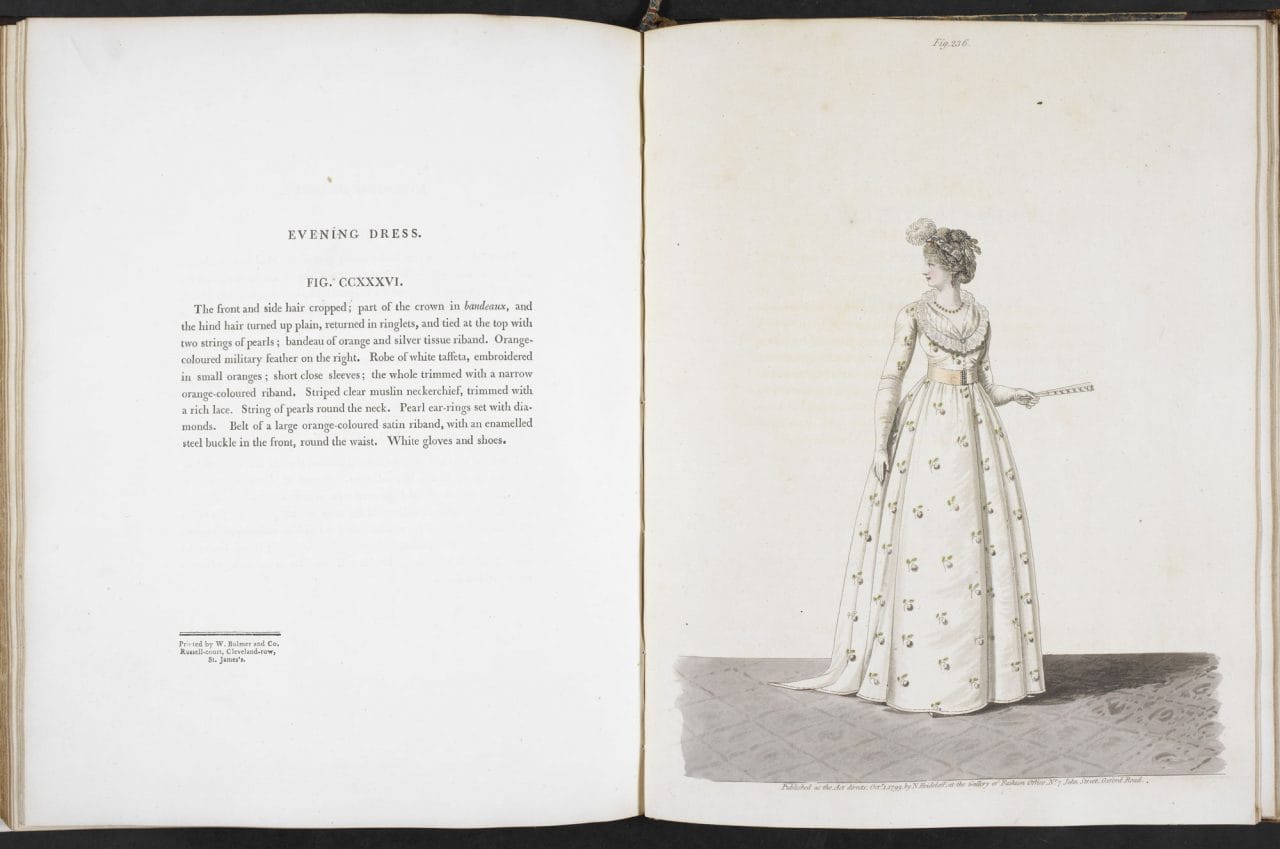

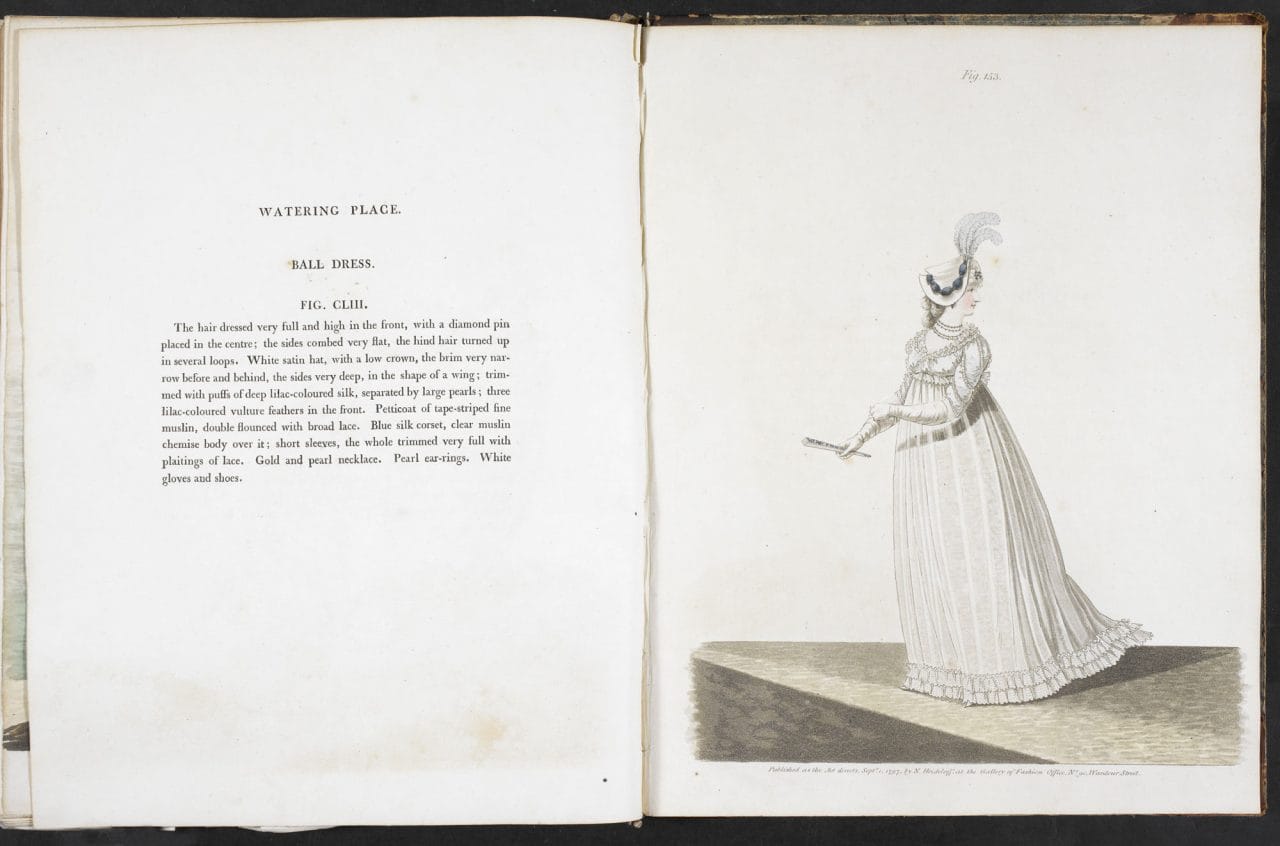

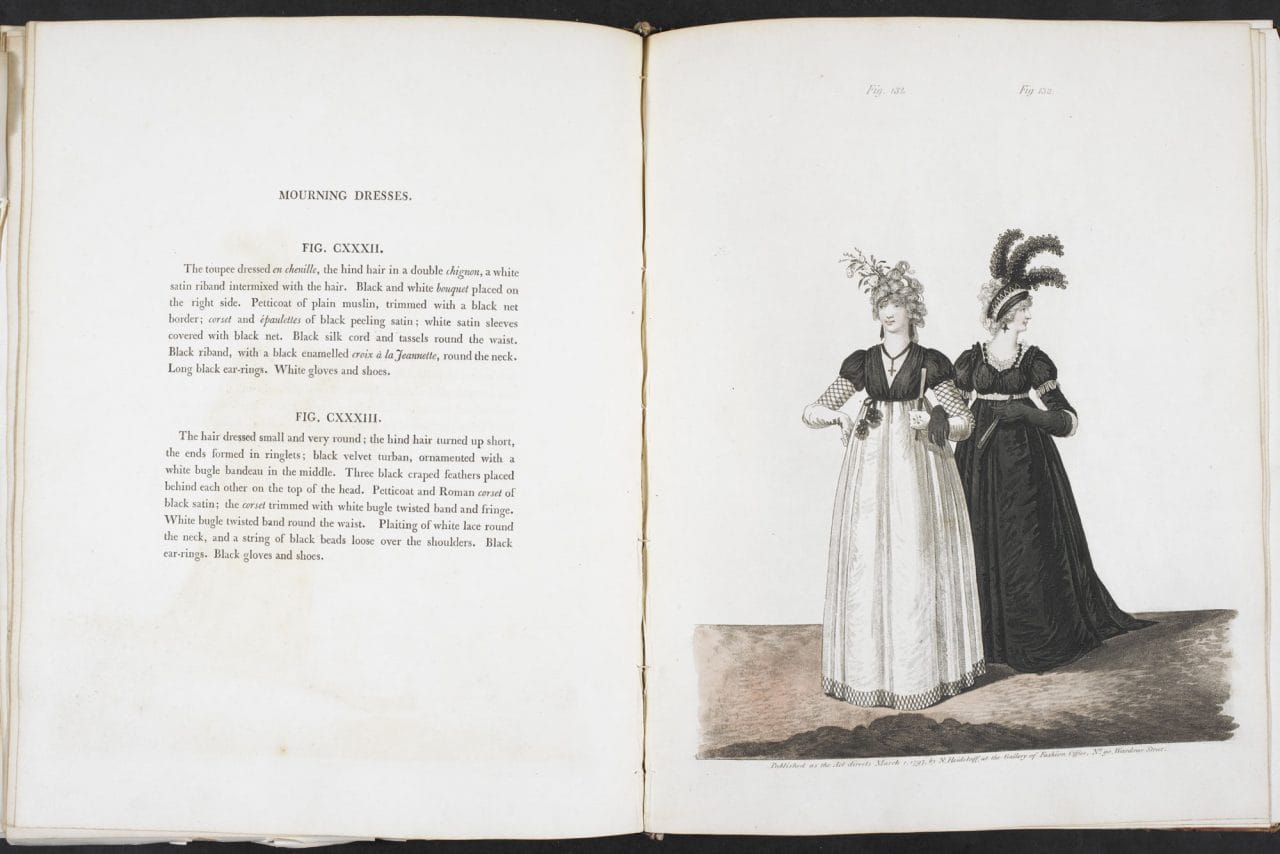

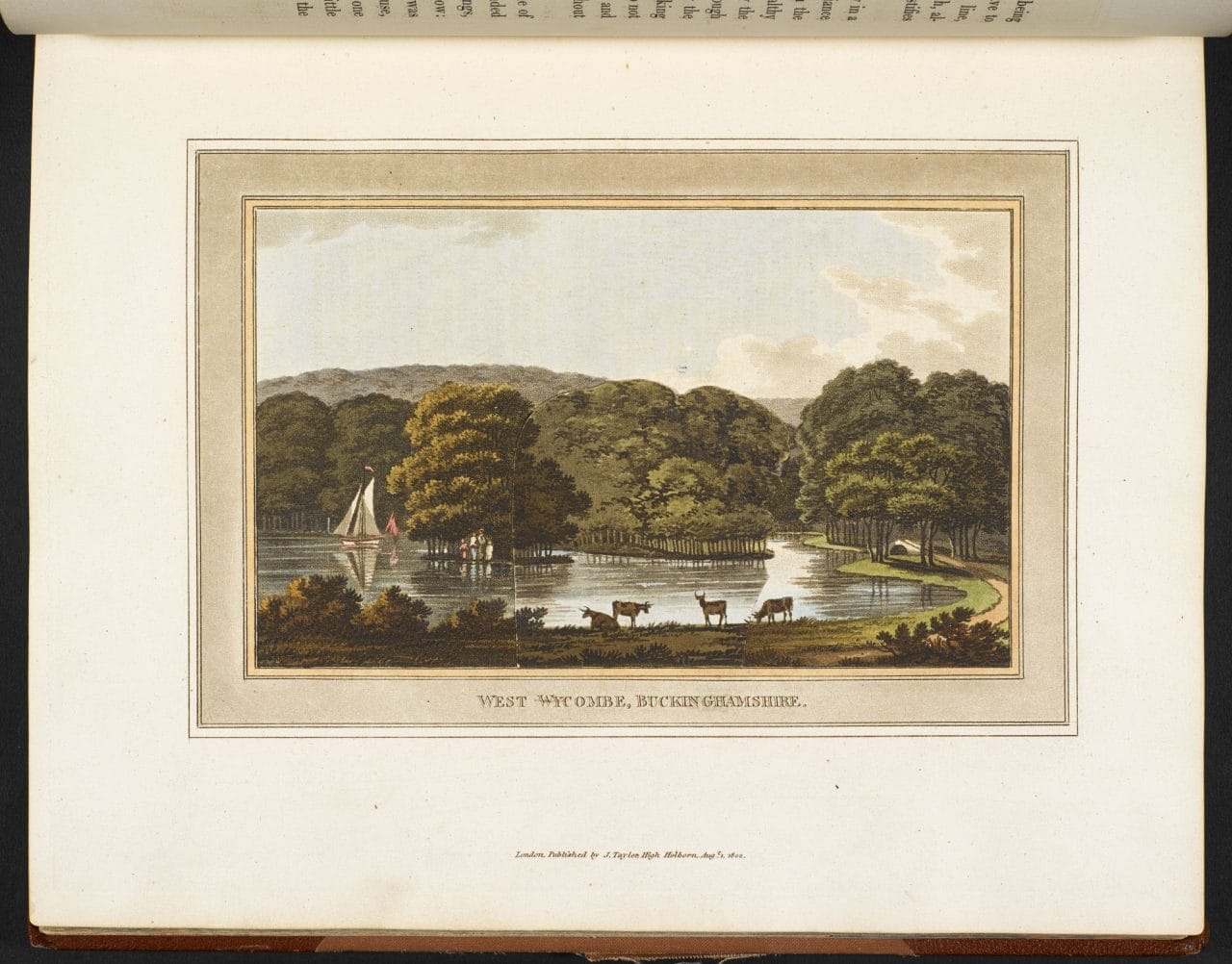

By contrast, and from the beginning, her readers saw that Jane Austen was doing something new with the novel, that she was using it to describe probable reality and the kinds of people one felt one already knew. The narratives of her heroines play out within the realms of the possible. They are set in southern England, in places and a landscape Austen knew well. As Scott suggested, her plots are minimal and the adventures her heroines meet with are no more than the experiences of her readers: preparations for a dance, an outing to the seaside, a picnic. Austen used fiction to describe social reality within her own time and class (the gentry and professional classes of southern England in the early 19th century). By so doing, she was able to introduce something closer to real morality in describing the range of human relationships that we all are likely to encounter in ordinary life. Her subjects are the behaviour of parents to their children, the dangers and pleasures of falling in love, of making friends, of getting on with neighbours, and above all of discriminating between those who mean us well and those who may not.

Jane Austen’s social realism includes her understanding that women’s lives in the early 19th century are limited in opportunity, even among the gentry and upper middle classes. She understands that marriage is women’s best route to financial security and social respect. Many of the crucial events of her stories take place indoors, in the female space of the drawing room. Often her plots move forward by means of overheard conversations. She writes some of the most natural and real-seeming conversations in literature. Rumour places a large part in transmitting news, and in her small, enclosed communities, everyone is a gossip.

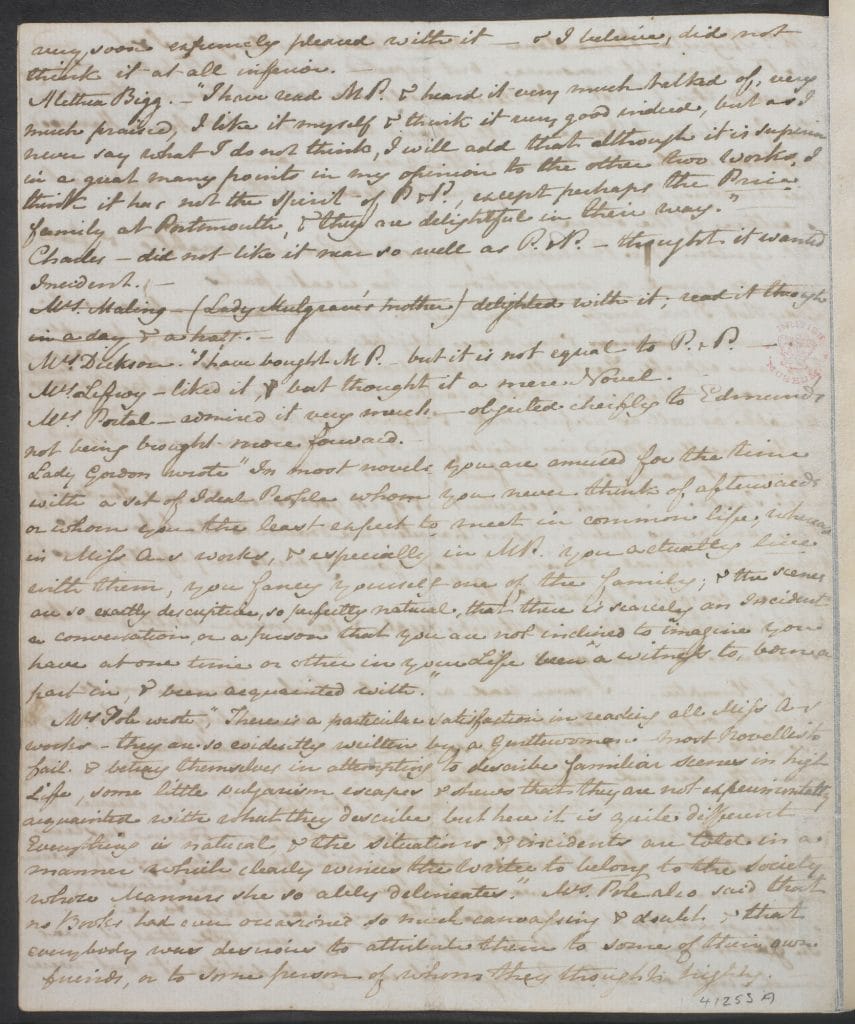

Contemporary responses

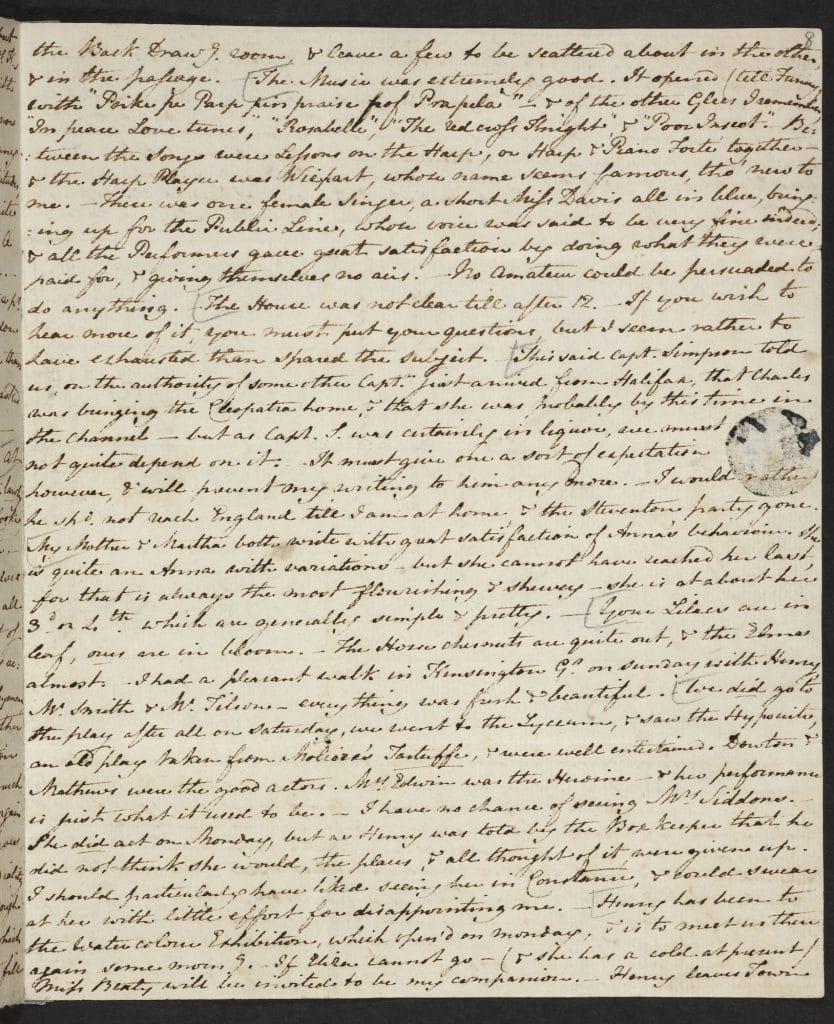

‘[T]here is scarcely an Incident or conversation, or a person that you are not inclined to imagine you have at one time or other in your Life been a witness to, born a part in, & been acquainted with’, observed one reader, whose impressions Austen recorded in Opinions of Mansfield Park. The contemporary novelist, Walter Scott, reviewing Emma in 1816 described it as ‘keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life’ and, he continued, ‘Emma has even less story than [Jane Austen’s] preceding novels.’ This may seem like an odd kind of compliment but Scott meant it as the highest praise. Ten years later, in March 1826, he wrote in his diary: ‘[R]ead again and for the third time at least Miss Austen’s very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with.’

Combining realism, romance and comedy

To say that Austen is a realist as a writer is not quite the same as saying she describes society as it really is. Her novels are also romantic comedies. In novel after novel, love and good fortune win out and the future looks perfect for the handsome young couple whose union is finally confirmed in the closing pages. This happens despite the fact that many married couples are portrayed as ill-suited or ridiculous (think of Mr and Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice or Mr and Mrs Elton in Emma). Realism is a literary device rejecting escapism and extravagance to produce a lifelike illusion and not a direct translation of reality.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Kathryn Sutherland

Kathryn Sutherland is a Professorial Fellow in English at St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford. Her research interests include writings from the romantic period, Scottish Enlightenment, textual theory and Jane Austen. She is currently directing an AHRC research project: Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition and Print Edition (to be published by Oxford University Press).