Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre

出版日期: 1847 文学时期: Victorian

Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel, Jane Eyre, secured her status as one of the greatest Victorian novelists. It tells the story of an orphan girl turned governess who overcomes hardships and setbacks to marry her beloved employer, Mr Rochester. It is also a passionate expression of the rights of women who lacked the money and social connections to make their voices heard. Denounced by some contemporary reviewers for Jane’s ‘unchristian’ rebellion against her lowly status, Jane Eyre has been seen since as an archetypal love story, a key text in the feminist canon and a classic example of Victorian Gothic.

What is Jane Eyre about?

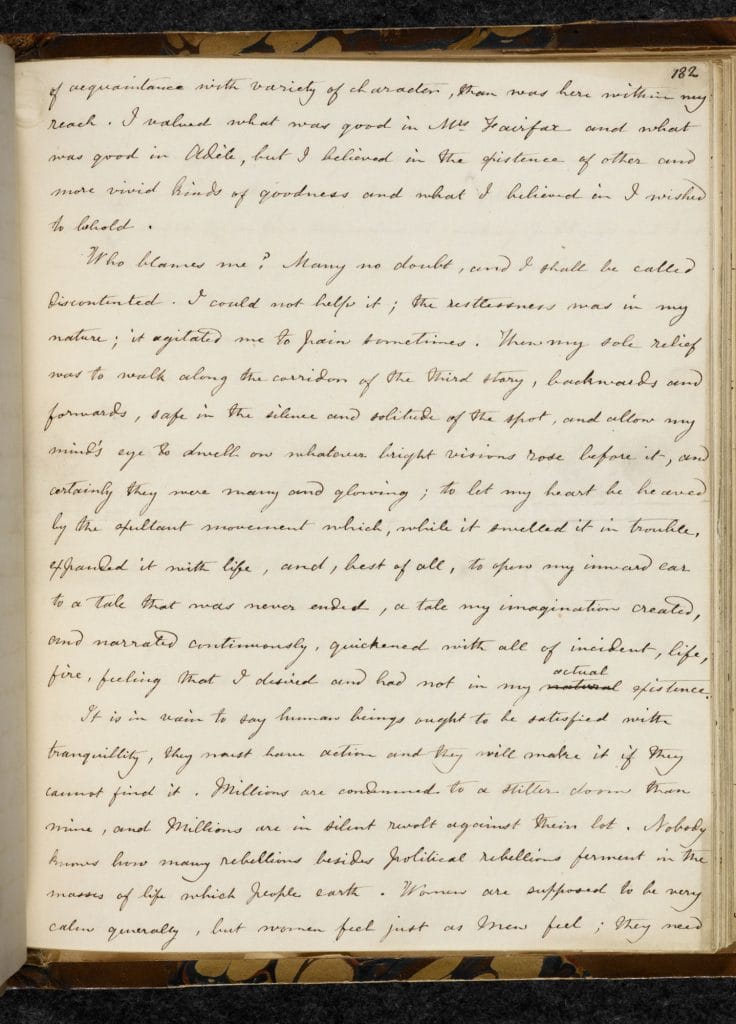

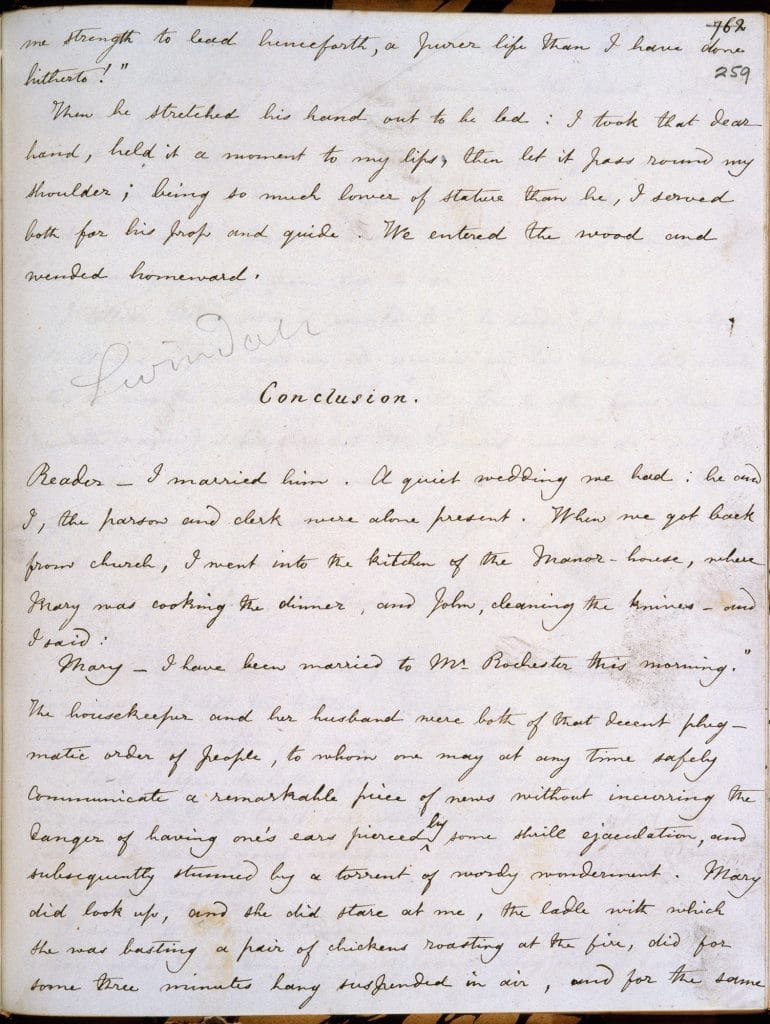

Charlotte Brontë’s iconic novel was originally subtitled ‘An Autobiography’. In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë created ‘a heroine as plain, and as small as myself, who’, she told her sisters, ‘shall be as interesting as any of yours’. Indeed, Jane’s ordinariness as well as her extraordinary passion are key elements of her enduring appeal. In creating a young heroine who works, demands respect and combines self-control with intense emotion and rebellion, Charlotte directly challenged 19th-century conceptions of appropriate female behaviour and attitudes towards children. Brontë’s intimate and immediate first-person narrative placed the reader for the first time directly in the mind of the rebellious child and the outspoken woman, addressing its reader head on from its opening lines right to its famous close: ‘Reader, I married him’.

Jane Eyre is an example of a Bildungsroman: a story that that follows its heroine’s journey from childhood to adulthood. The title character, Jane, is a bullied but rebellious orphan. She suffers neglect first in the household of her unloving aunt, and later at Lowood School as a half-starved pupil and then as a teacher. She eventually becomes a governess at Thornfield Hall, where she is to care for Adele, the ward of the mysterious Mr Edward Rochester. A romance blossoms between the governess and her employer, who eventually proposes to her. But Rochester holds a dark secret: he is already married, to an insane woman incarcerated in the attic.

This tale of a headstrong governess is a curious mixture of fantasy, romance and realism, that speaks not just of Brontë’s wild imagination but her keen observation of daily life. Indeed Jane Eyre draws heavily on the author’s own attempts to make her way in life as the daughter of a Yorkshire parson, and Jane’s miserable childhood years at Lowood have their roots in Brontë’s early school experiences.

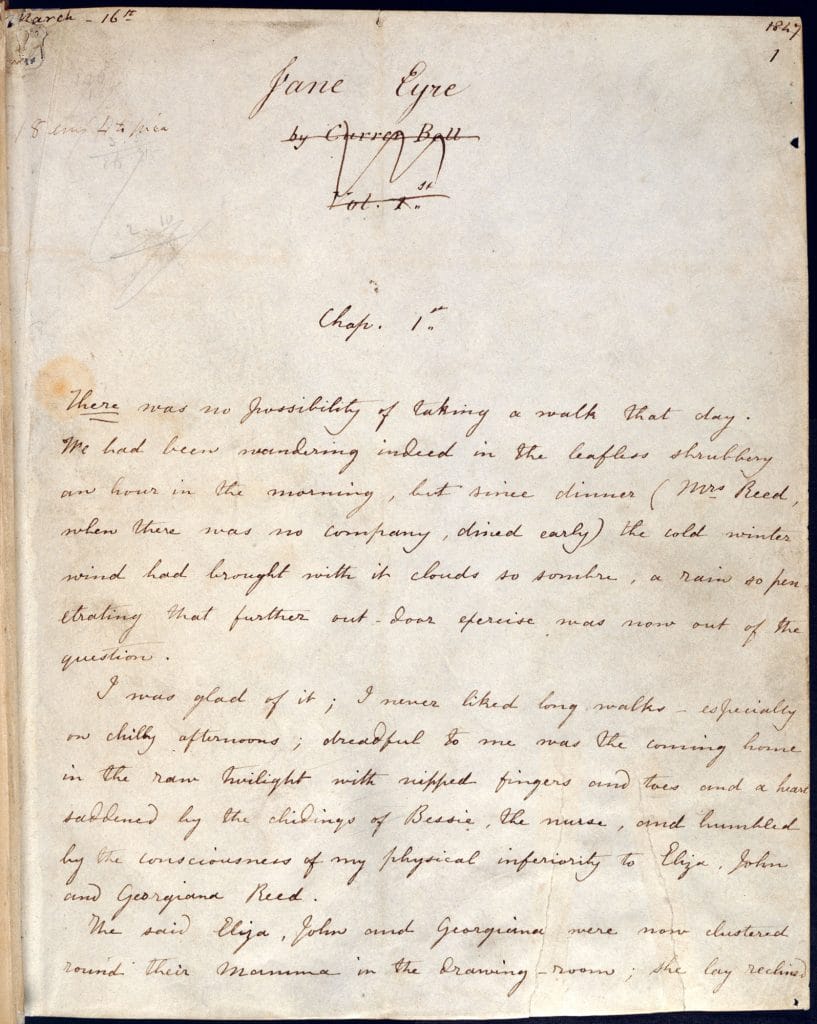

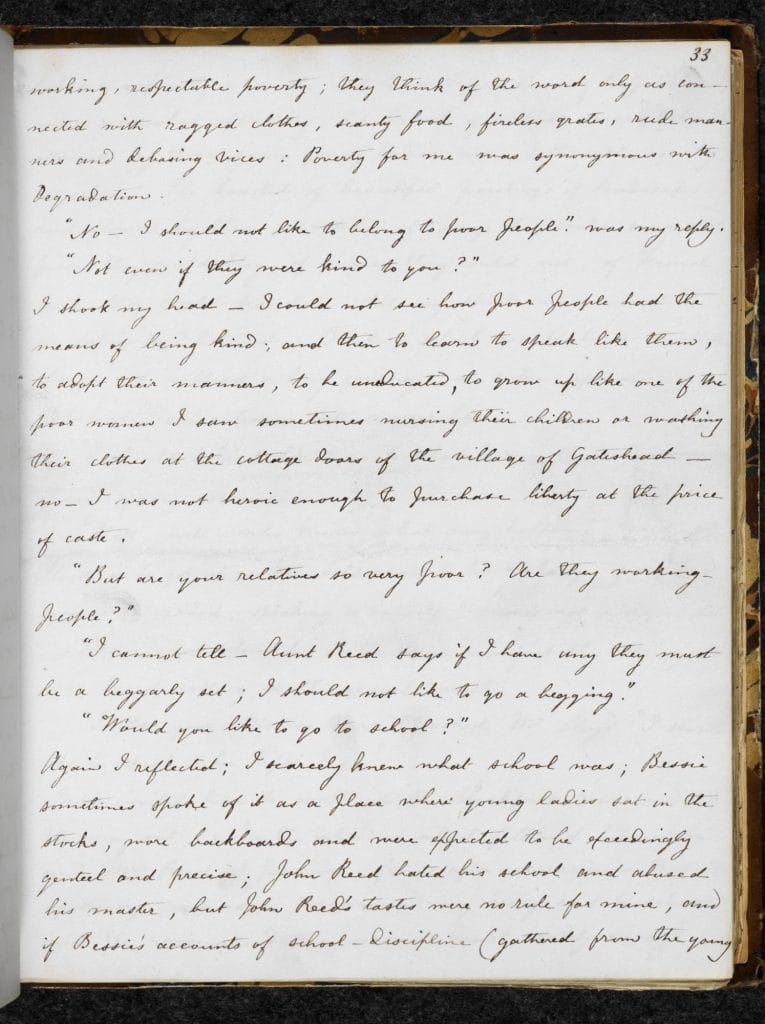

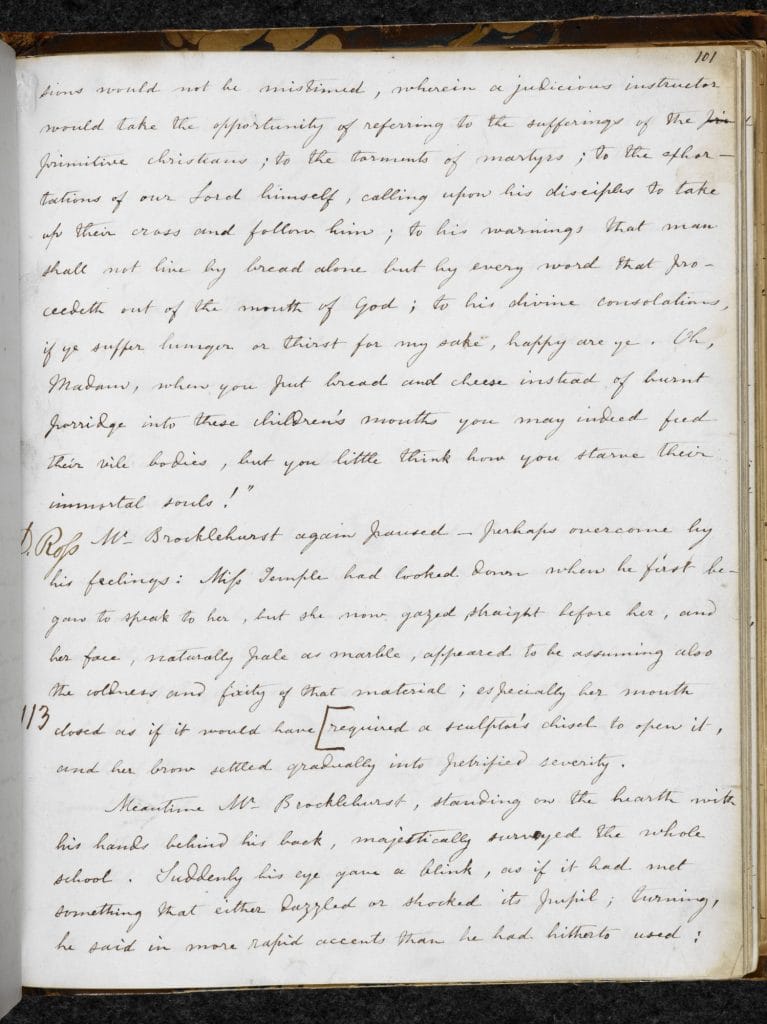

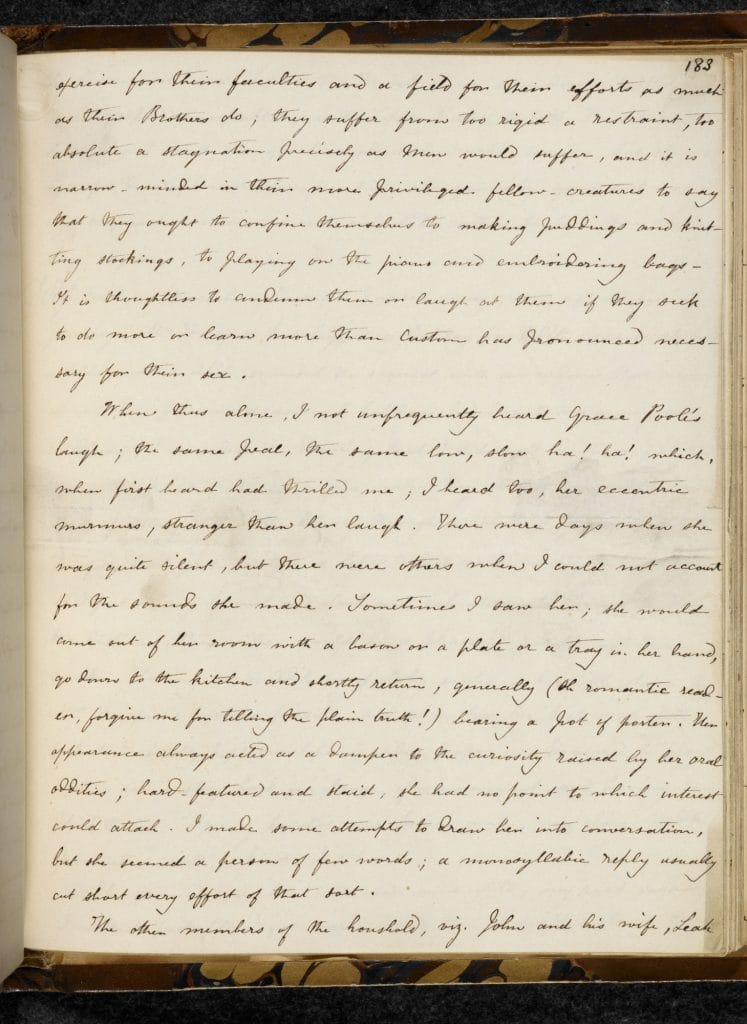

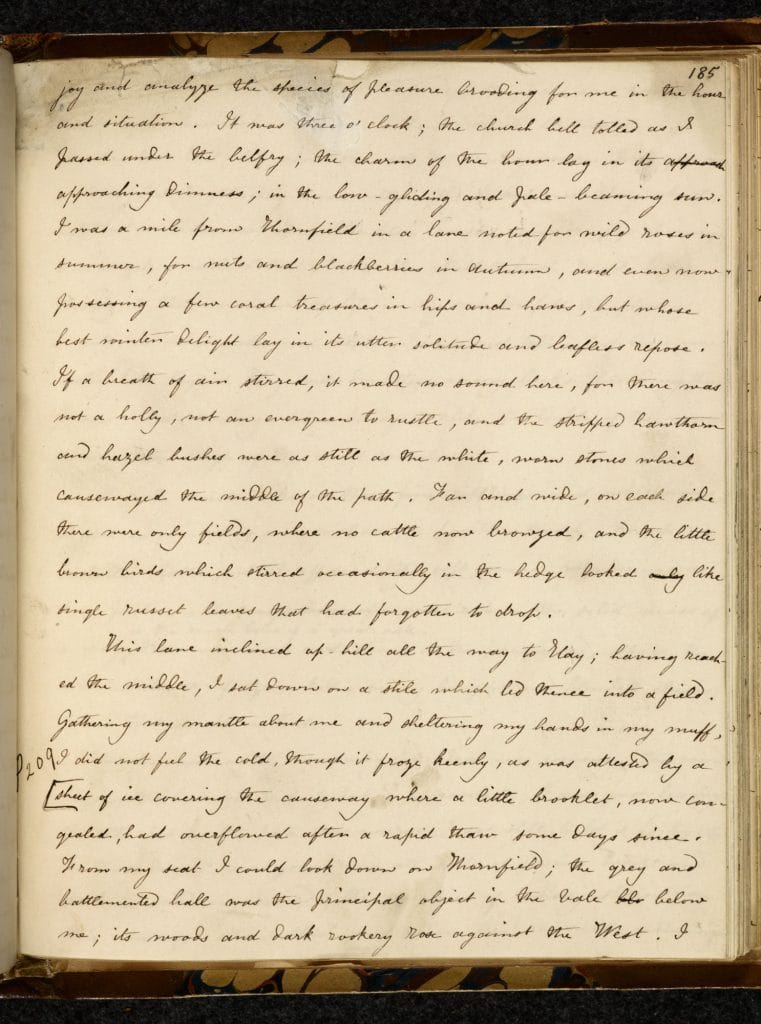

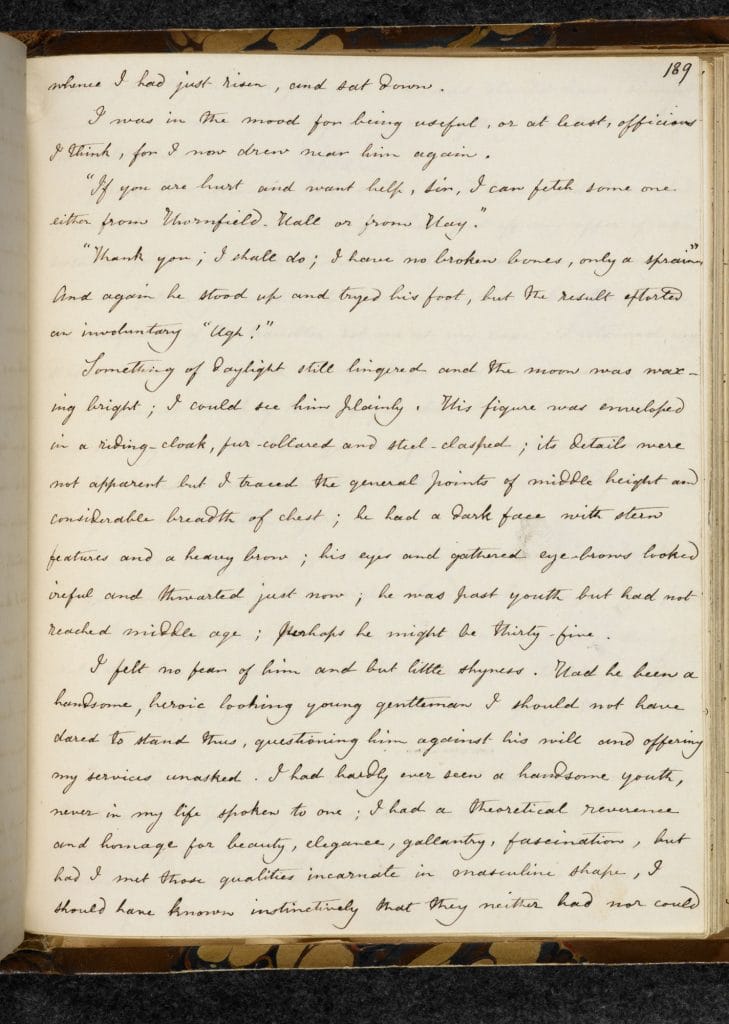

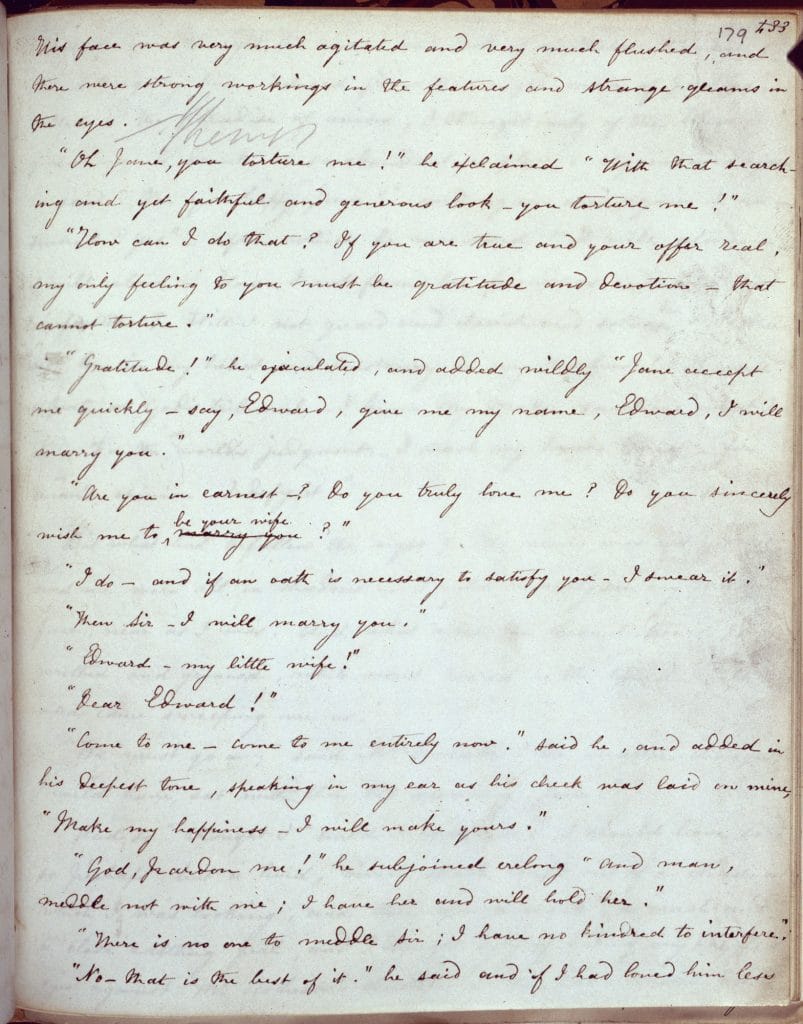

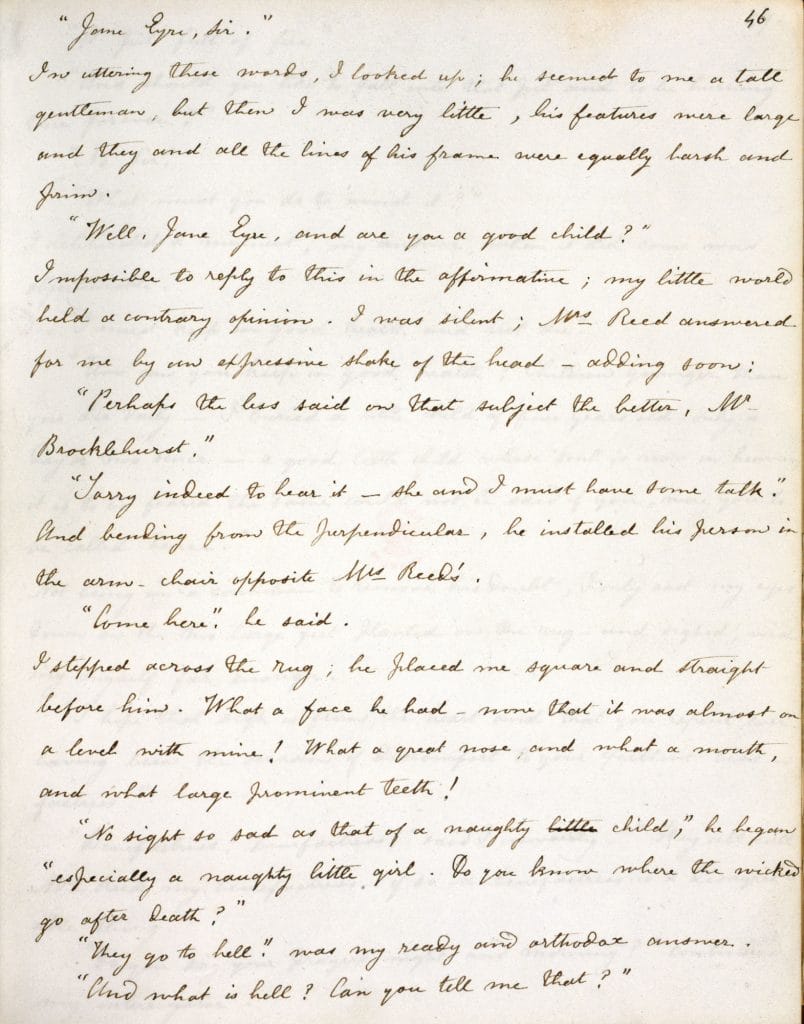

What does the manuscript reveal?

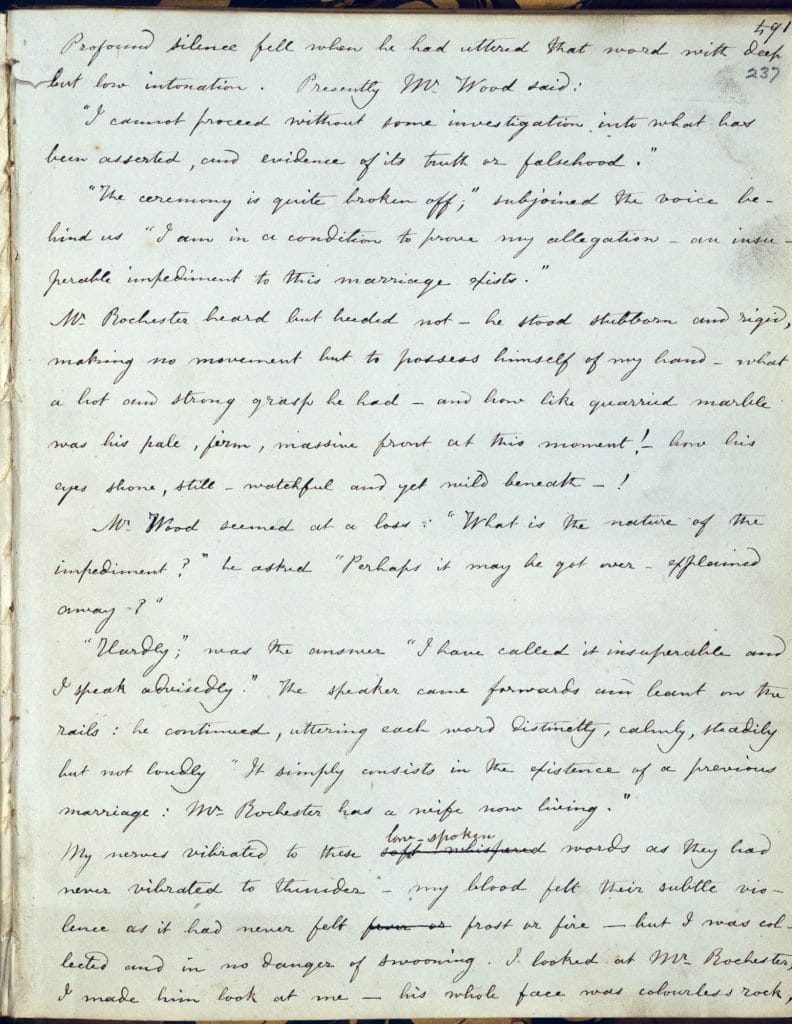

The manuscript shown here is Brontë’s autograph fair copy. It is remarkably neat, with very few corrections: ‘She would wait patiently’ her biographer Elizabeth Gaskell noted, ‘searching for the right term, until it presented itself to her’. Of the few revisions that Brontë made, the most significant serve to emphasise Jane’s strength of will in her encounters with Rochester. For instance, Brontë chose to play down Jane’s physical imperfections, crossing through Jane’s self-deprecating comparison of her physical form with Blanche Ingram’s, and deleting Rochester’s corresponding remark: ‘I will graciously excuse deficiencies’. Also cancelled is a line further on, in which Jane declares Rochester to be her ‘alpha and omega of existence’. In another scene she hastily withdraws her hand from contact with Rochester’s, but in the revised passage she crushes his hand ‘and thrust it back to him red with the passionate pressure’. These changes underline Jane Eyre’s refusal to be subjugated to anyone, even Rochester.

Writing under a pseudonym

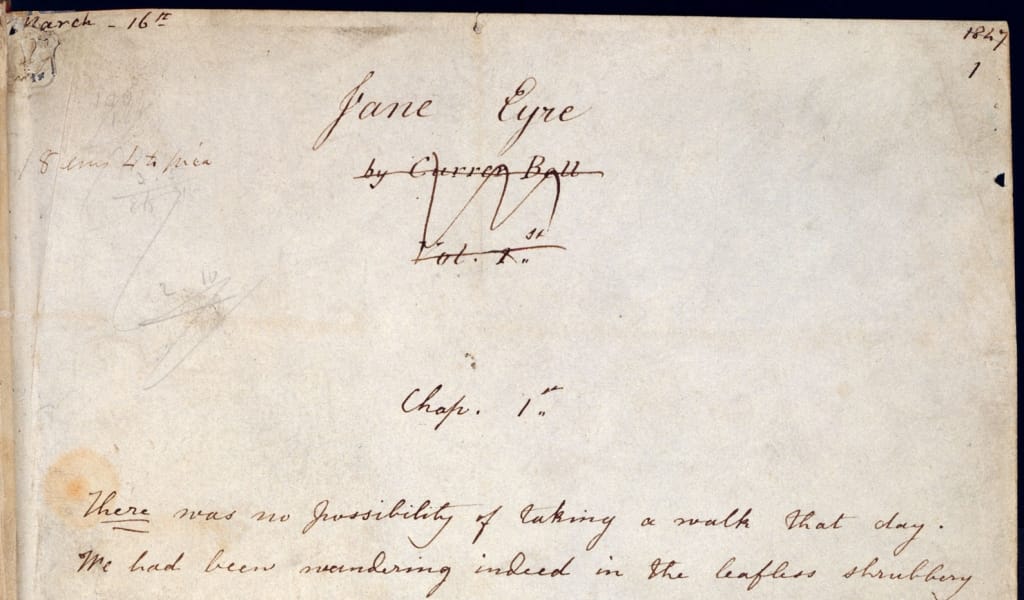

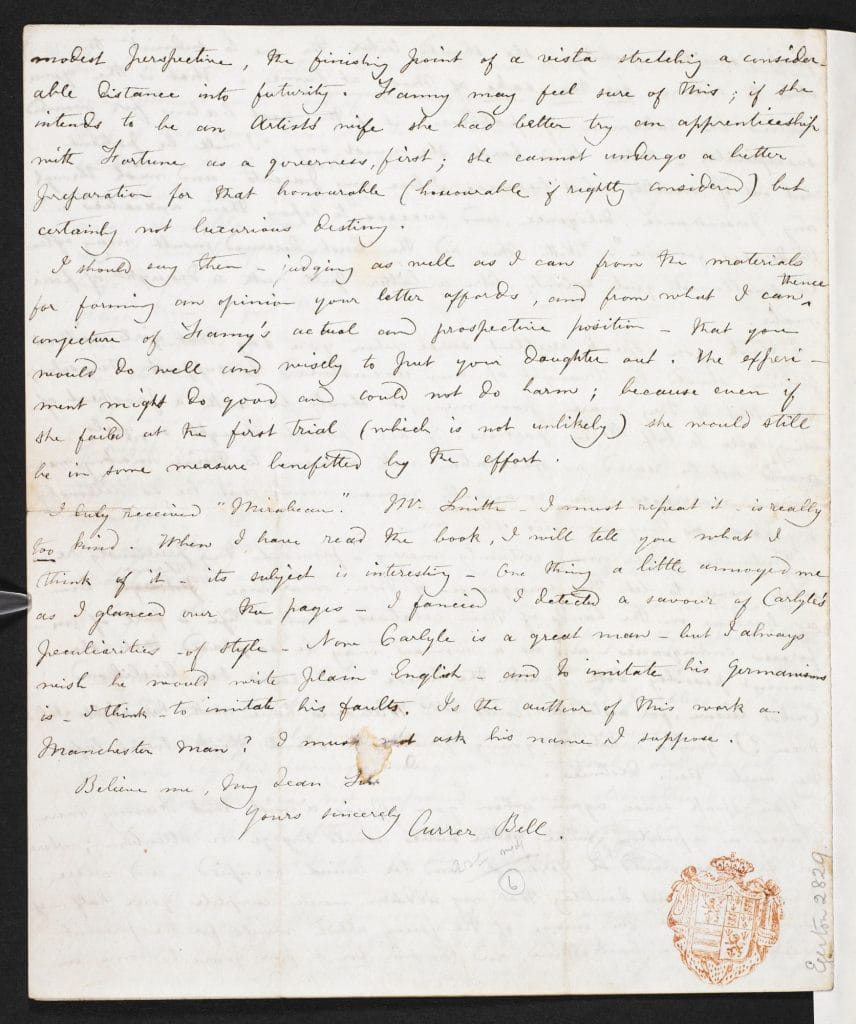

At the top of the title page can be seen Brontë’s pen name, ‘Currer Bell’. She expressed a number of reasons for wishing to be anonymous. Firstly, that it would ‘fetter me intolerably’ when writing, to know that acquaintances would read the works, and perhaps identify the real people and places behind their fictional counterparts. She was also conscious of a ‘vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked upon with prejudice’. Indeed many contemporary reviews insisted that the author could not possibly be a woman, revealing the entrenched, limiting attitudes towards women in the 19th century.

Childhood and a child’s perspective

Charlotte Brontë was the third of six children of Patrick Brontë, an Irish crofter’s son who rose via a Cambridge education to become, in 1820, perpetual curate at Haworth, in Yorkshire. Charlotte was only five in 1821 when her mother Maria died. Four years later, typhoid fever hit Cowan Bridge, the Clergy Daughters’ School which Charlotte and her three sisters all attended. The fever spread quickly through the school, exacerbated by the poor food and harsh regime, and there were a number of deaths among the students. Two of Charlotte’s sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, fell ill; after being sent home, they both died of tuberculosis in May and June, respectively. Shortly before Elizabeth’s death, Charlotte and Emily were removed from the school.

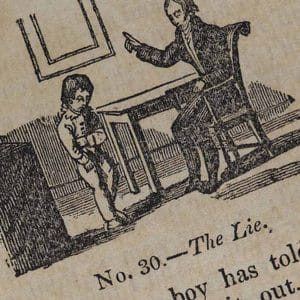

Charlotte’s experiences at Cowan Bridge provided inspiration for her portrayal of the harsh conditions at Lowood School in Jane Eyre. Her depiction of Jane’s defiance in the face of maltreatment at the hands of adults was highly unusual; never before had a novel given voice to a child standing up to injustice in this way. Brontë’s pioneering portrayal of sympathetic disobedience played an important part in changing Victorian views about childhood.

Extract from Chapter 4 of Jane Eyre, in which Mr. Brocklehurst interviews Jane about hell, sin, and the Bible. Read by Amanda Root. Audio source: Naxo

Education and rebelliousness

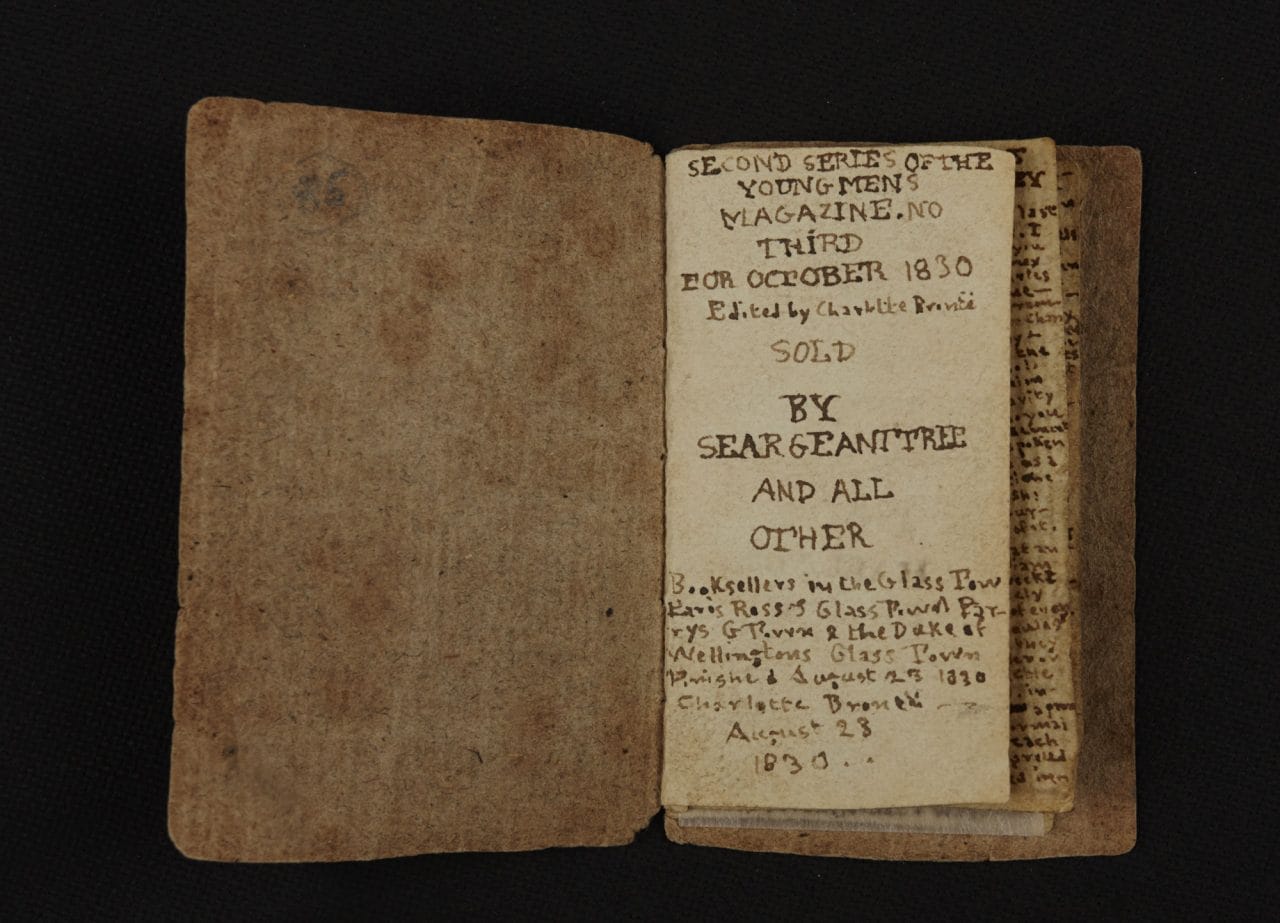

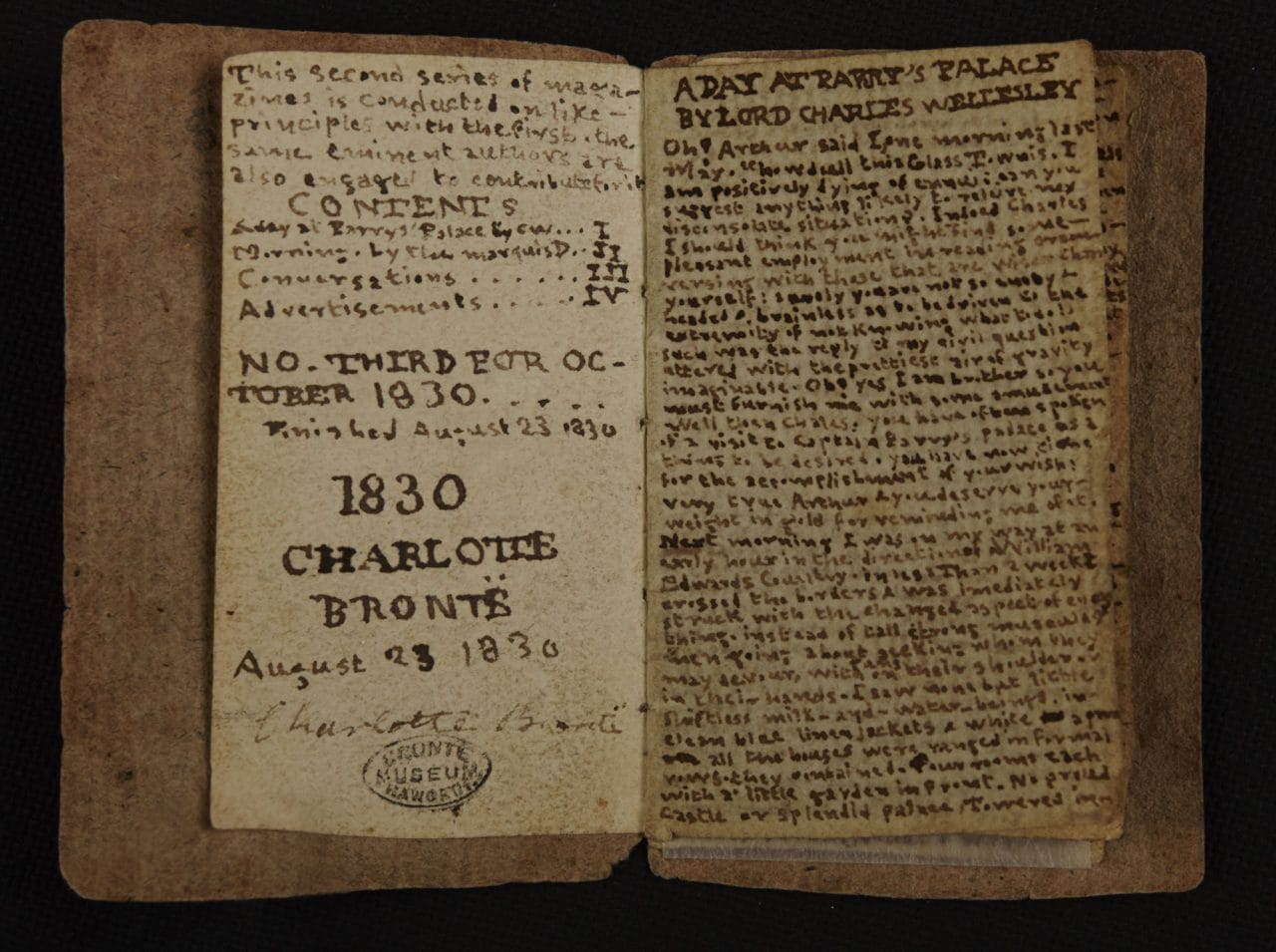

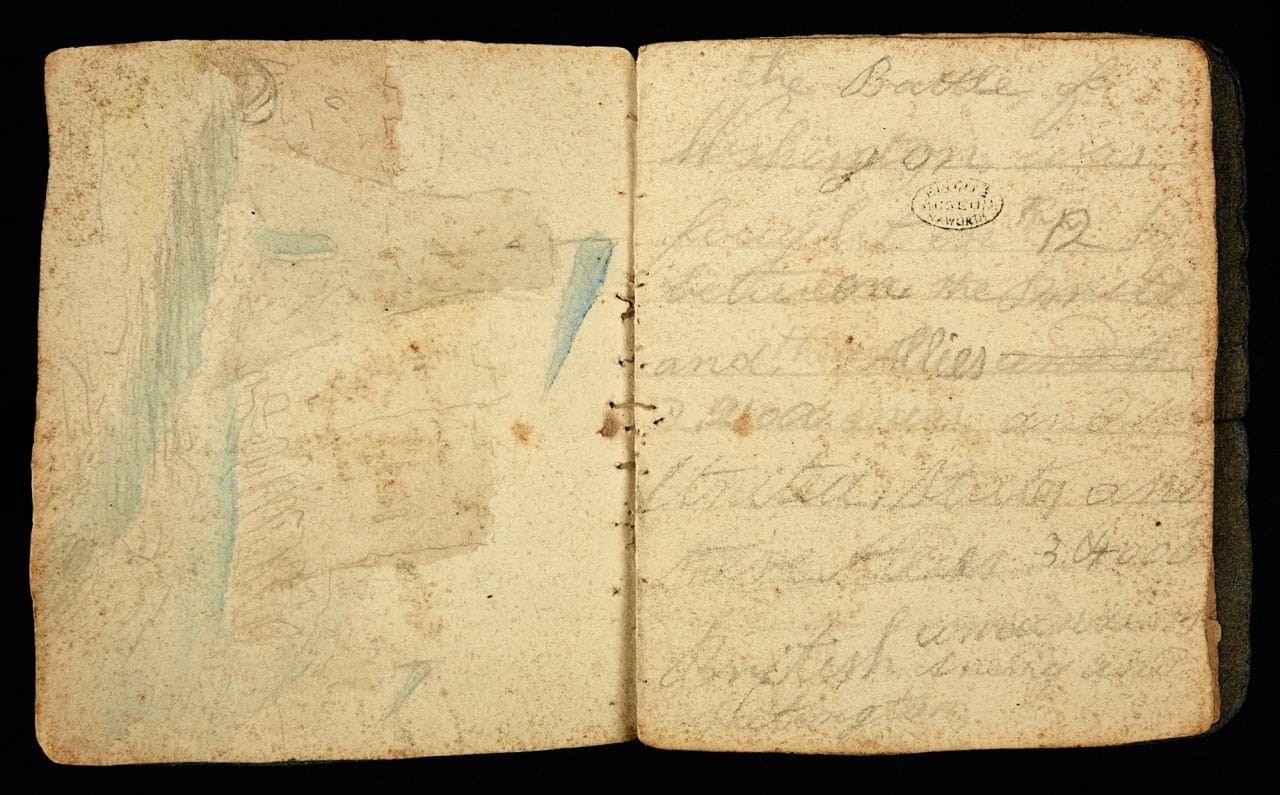

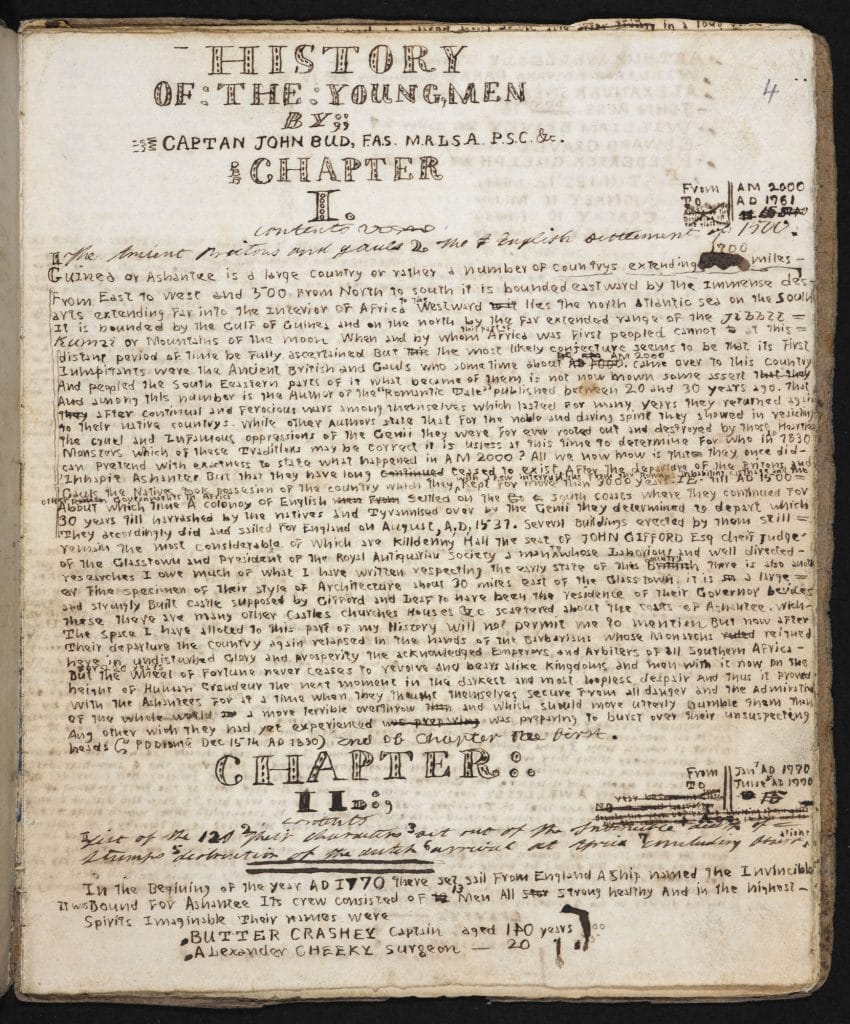

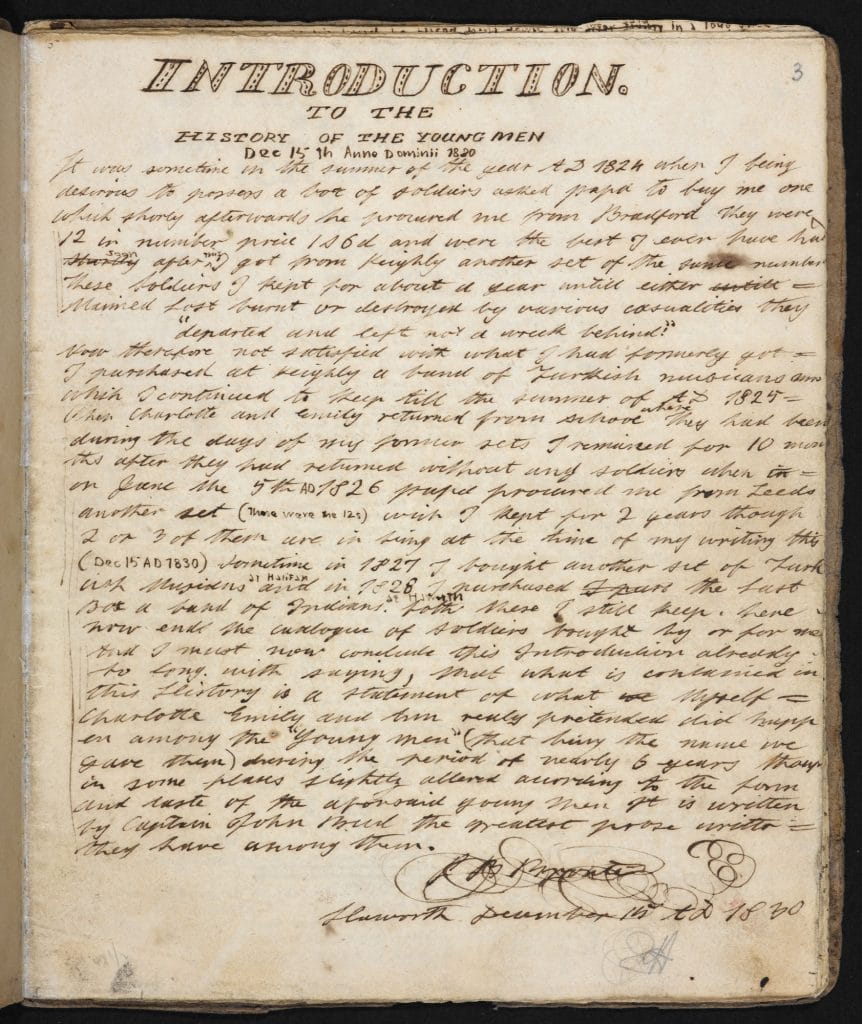

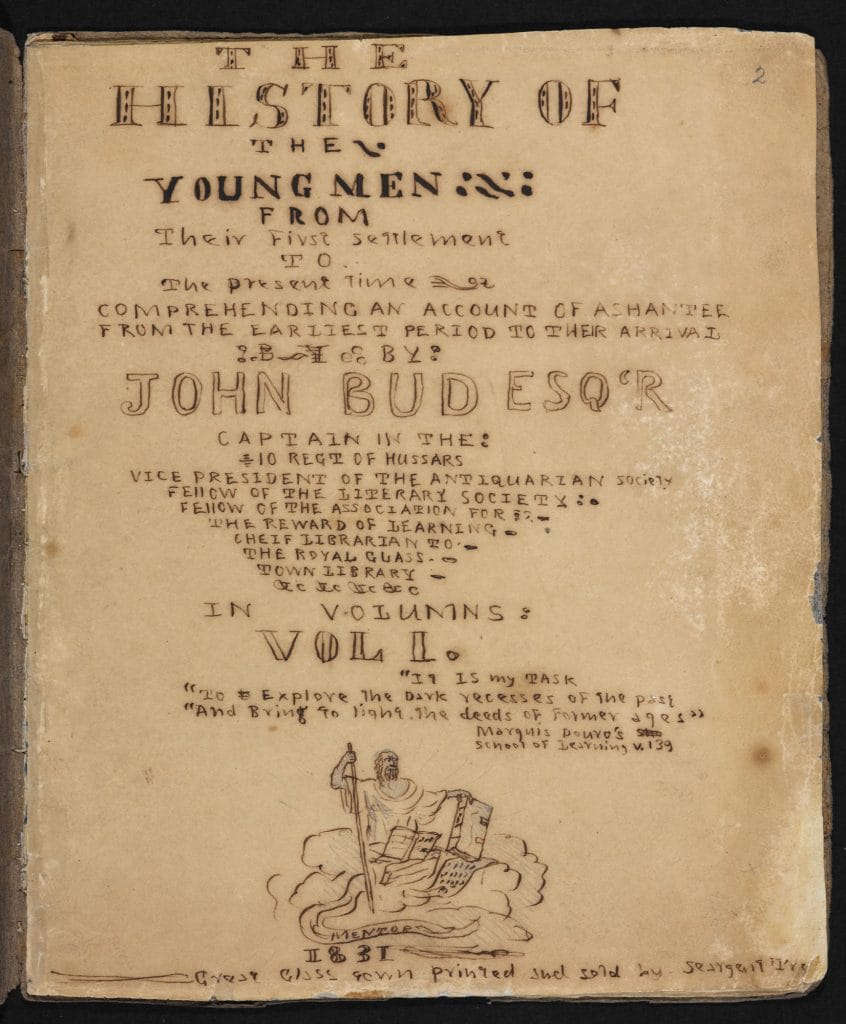

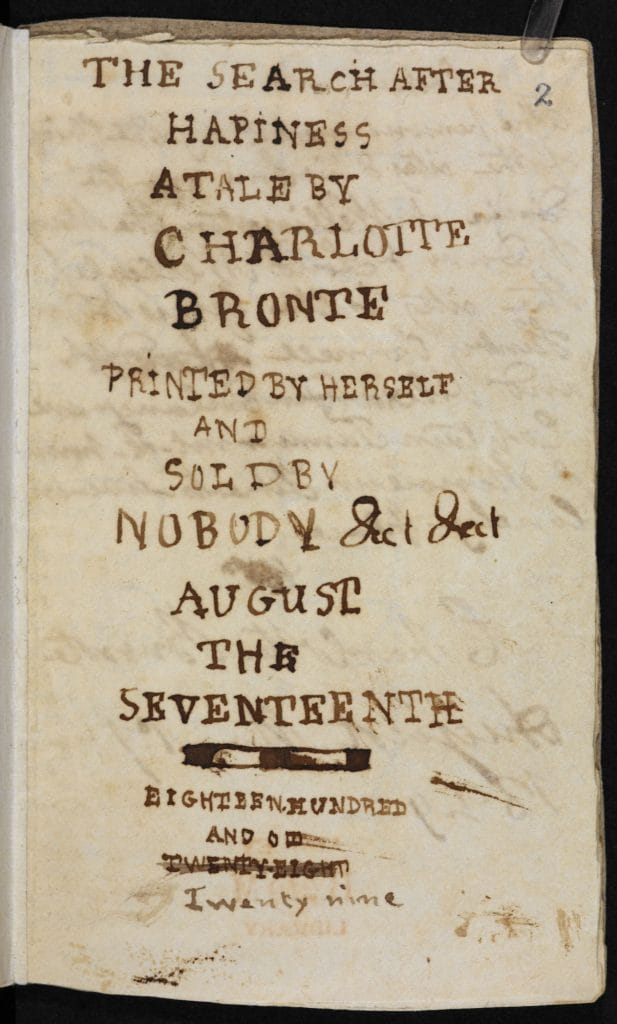

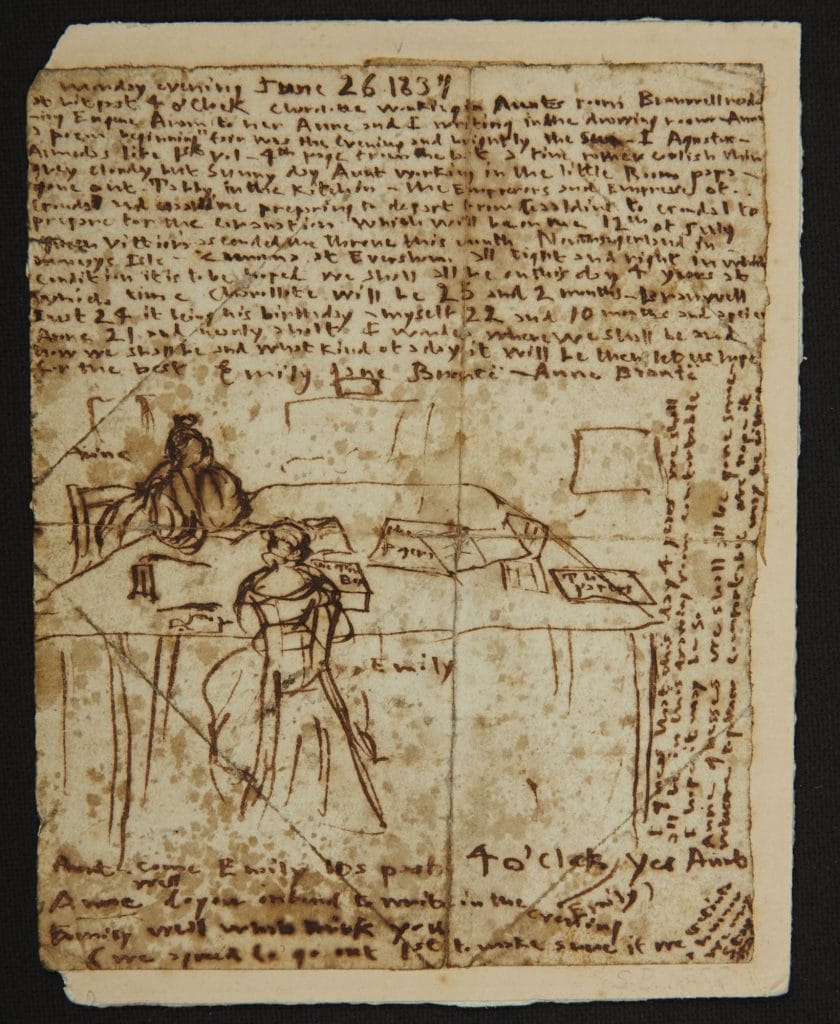

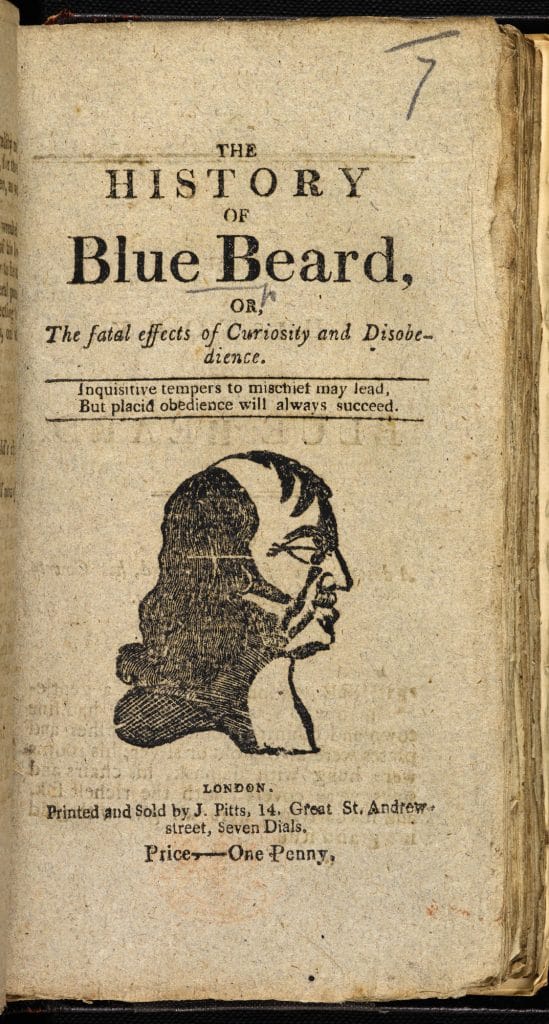

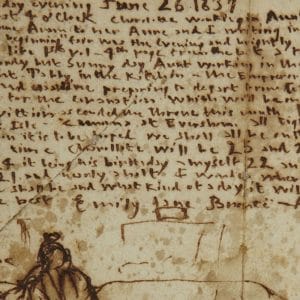

After the death of the two oldest Brontë daughters, the children were given a stimulating and wide-ranging education at home by their father, Patrick, and their aunt. Charlotte, her two younger sisters Anne and Emily, and their brilliant, unstable brother Branwell, invented complex imaginary worlds, which they wrote about extensively in tiny home-made books. The fantasy worlds that the Brontës created weren’t simply childhood fun – Charlotte continued to work on them well into her twenties. During Charlotte’s time as a teacher at Roe Head School, she kept a journal that contains not just accounts of everyday events at the school, but poetry, prose and vivid descriptions of life in her fantasy world of Agria , slipping effortlessly between real life and fiction. This combination of fantasy and realism, and the skill of slipping between many genres – Romance, Gothic, Realism – is in evidence throughout Jane Eyre.

As an adult, Charlotte worked as a governess and spent some years teaching at a boarding school in Brussels; her unrequited love for the school’s headmaster informed her novels Villette (1853) and The Professor (published posthumously in 1857). Jane Eyre was also clearly influenced by these experiences, exploring issues from the problem of low wages to the myriad sexual and emotional complexities which could, and did, arise in the relationship between employee and employer.

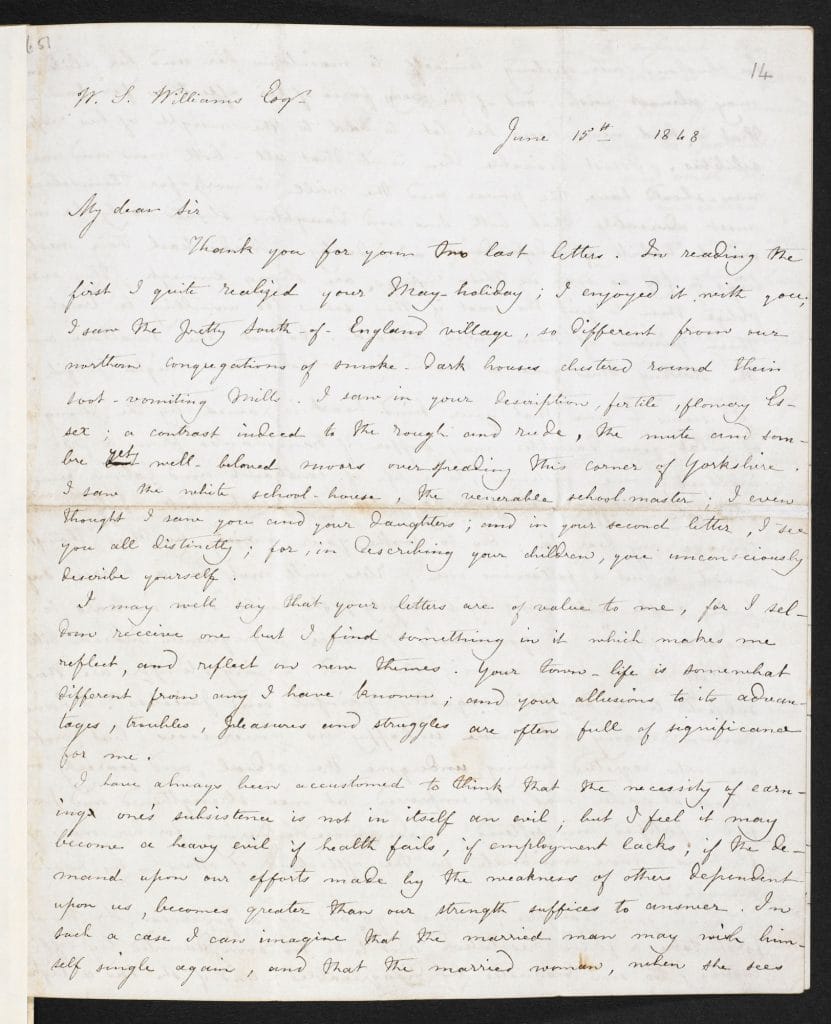

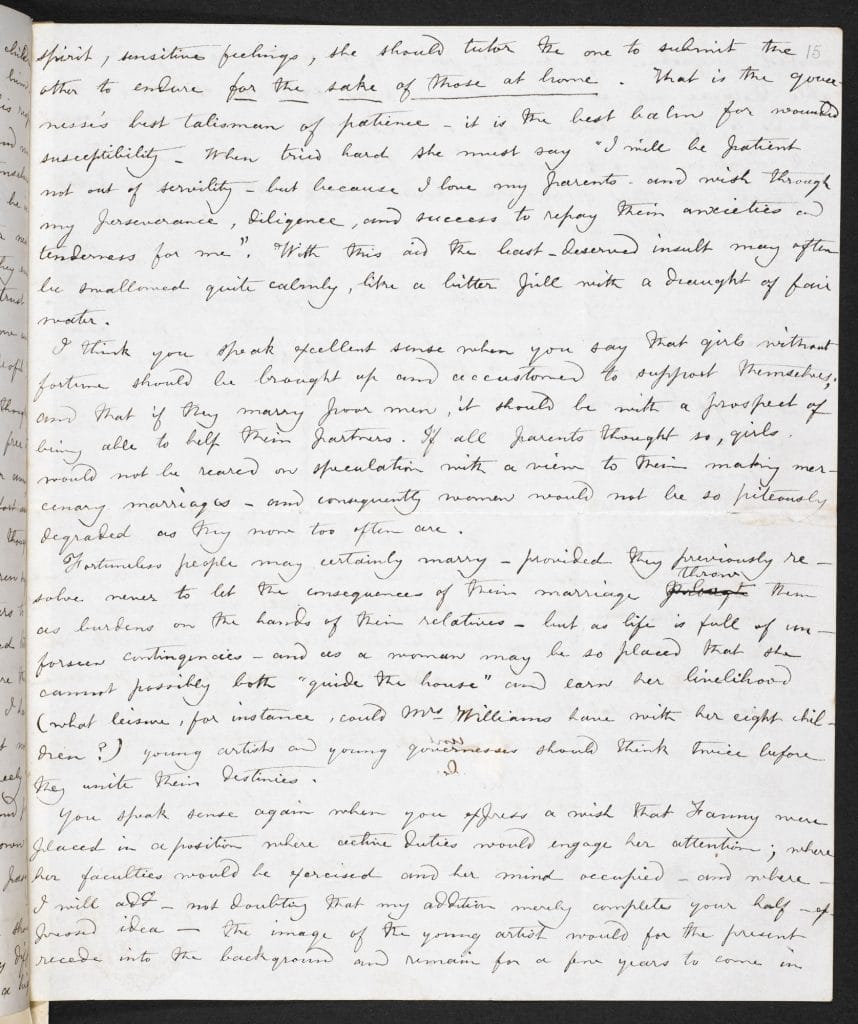

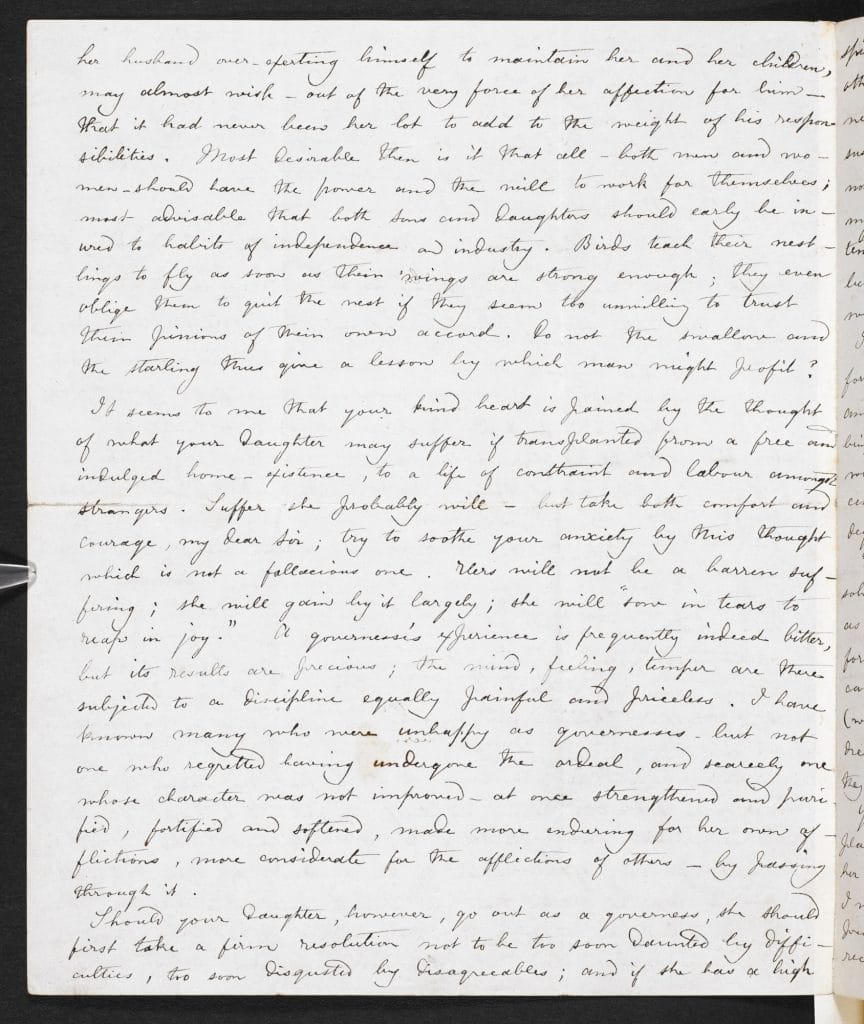

In this letter from Charlotte to W S Williams, written a year after the publication of Jane Eyre, Brontë considers both the drawbacks and the rewards of teaching: ‘A governess’ experience is frequently indeed bitter, but its results are precious…’. She goes on to argue how important it is for women to achieve financial and intellectual independence, highlighting a growing belief that women should receive an education that enables them to find employment:

Most desirable is it that all, both men and women, should have the power and will to work for themselves …

If all parents thought so [that girls should be accustomed to financially support themselves], girls would not be reared on speculation with a view to their making mercenary marriages; and, consequently, women would not be so piteously degraded as they now too often are.