The Rise of Consumerism

With increasing variety in clothes, food and household items, shopping became an important cultural activity in the 18th century. Dr Matthew White describes buying and selling during the period, and explains the connection between many luxury goods and slave plantations in South America and the Caribbean.

The Georgian period has been described by historians as the ‘age of manufactures’, a time when British men and women gained access to a dizzying range of material things.

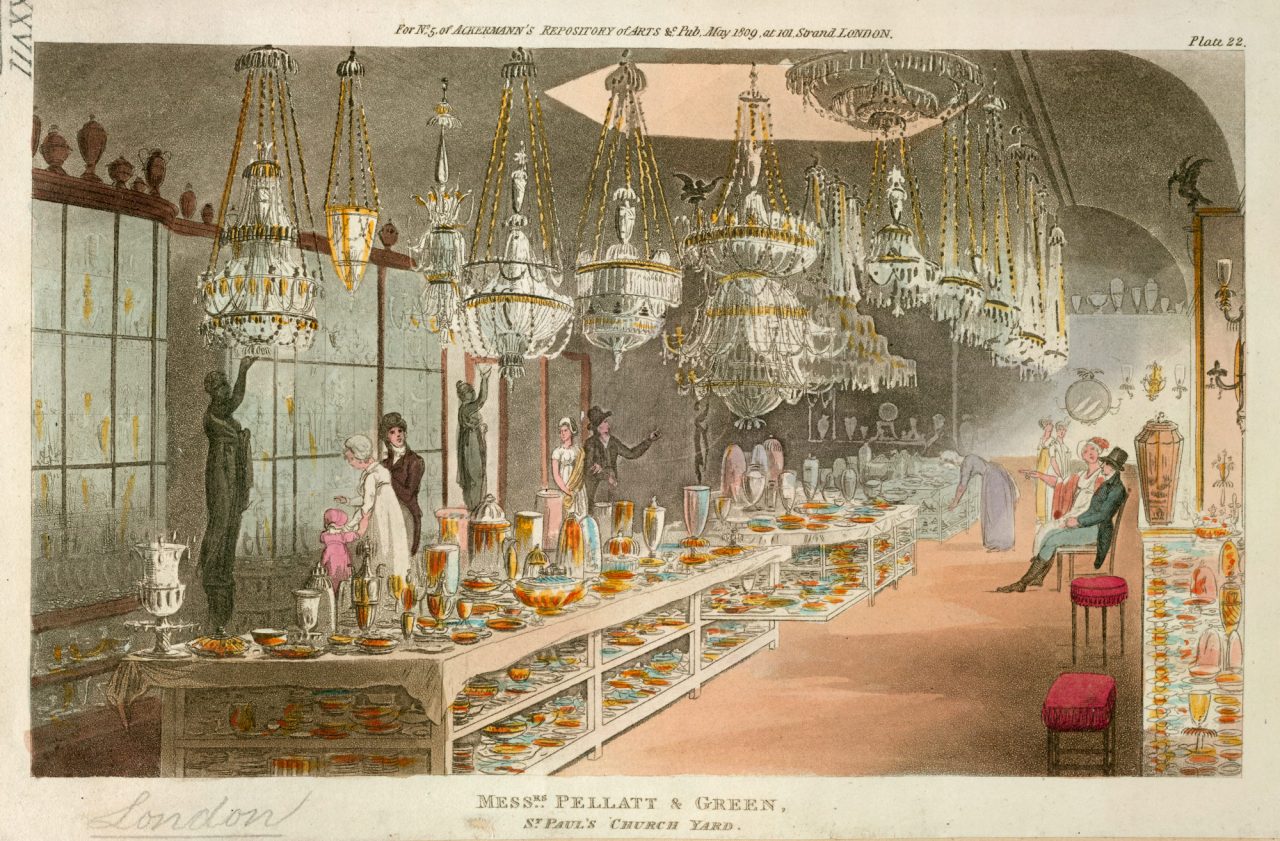

Image of Pellatt and Green’s glassware shop in St Paul’s Churchyard, London (1809), as an example of the rise in luxury goods in the early 19th century.

Shops and shopping

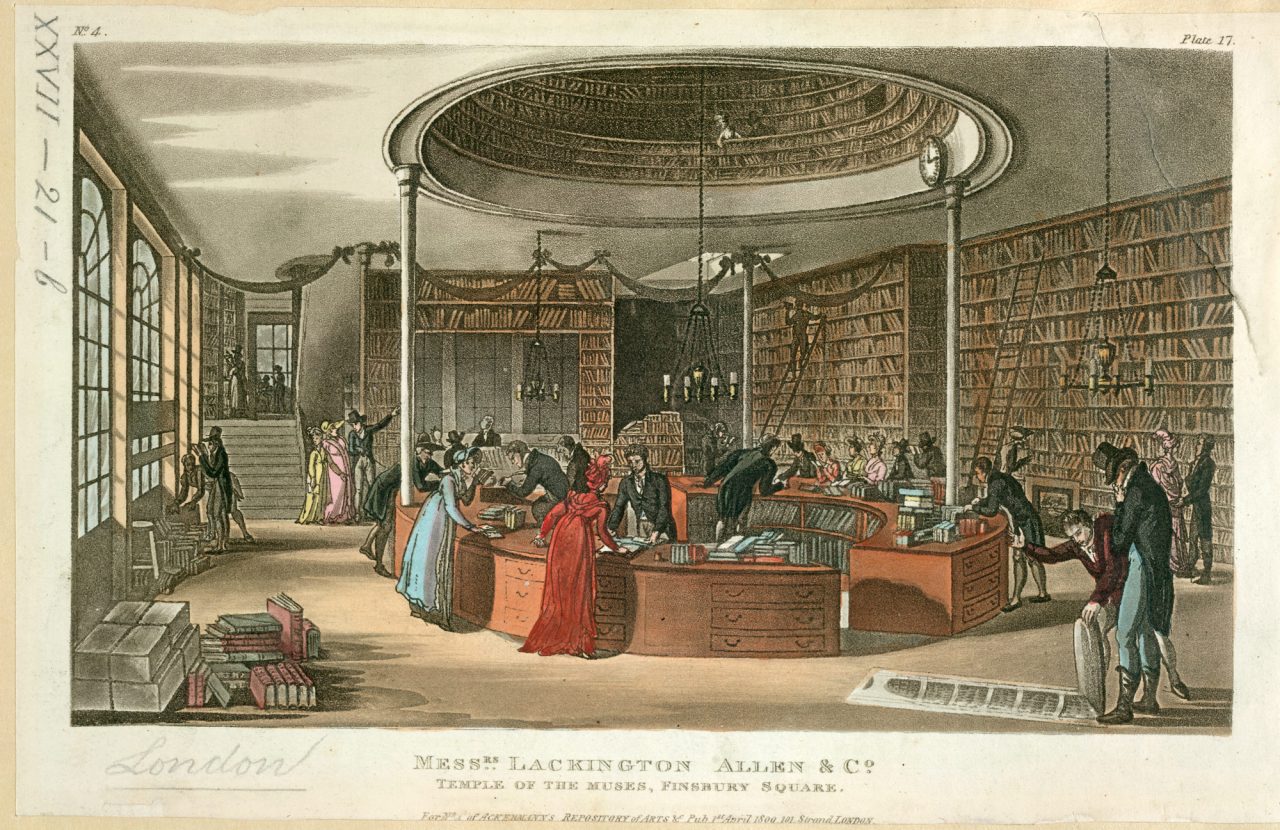

With improvements in transport and manufacturing technology, opportunities for buying and selling became faster and more efficient than ever before. And with the rapid growth of towns and cities, shopping became an important part of everyday life. Window shopping and the purchase of goods became a cultural activity in its own right, and many exclusive shops were opened in elegant urban districts: in the Strand and Piccadilly in London, for example, and in spa towns such as Bath and Harrogate.

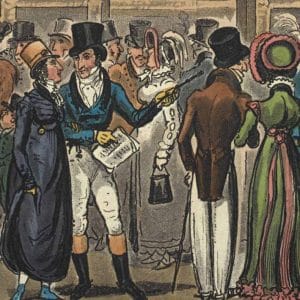

Depiction of shopping for fabric from Rudolph Ackermann’s The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics.

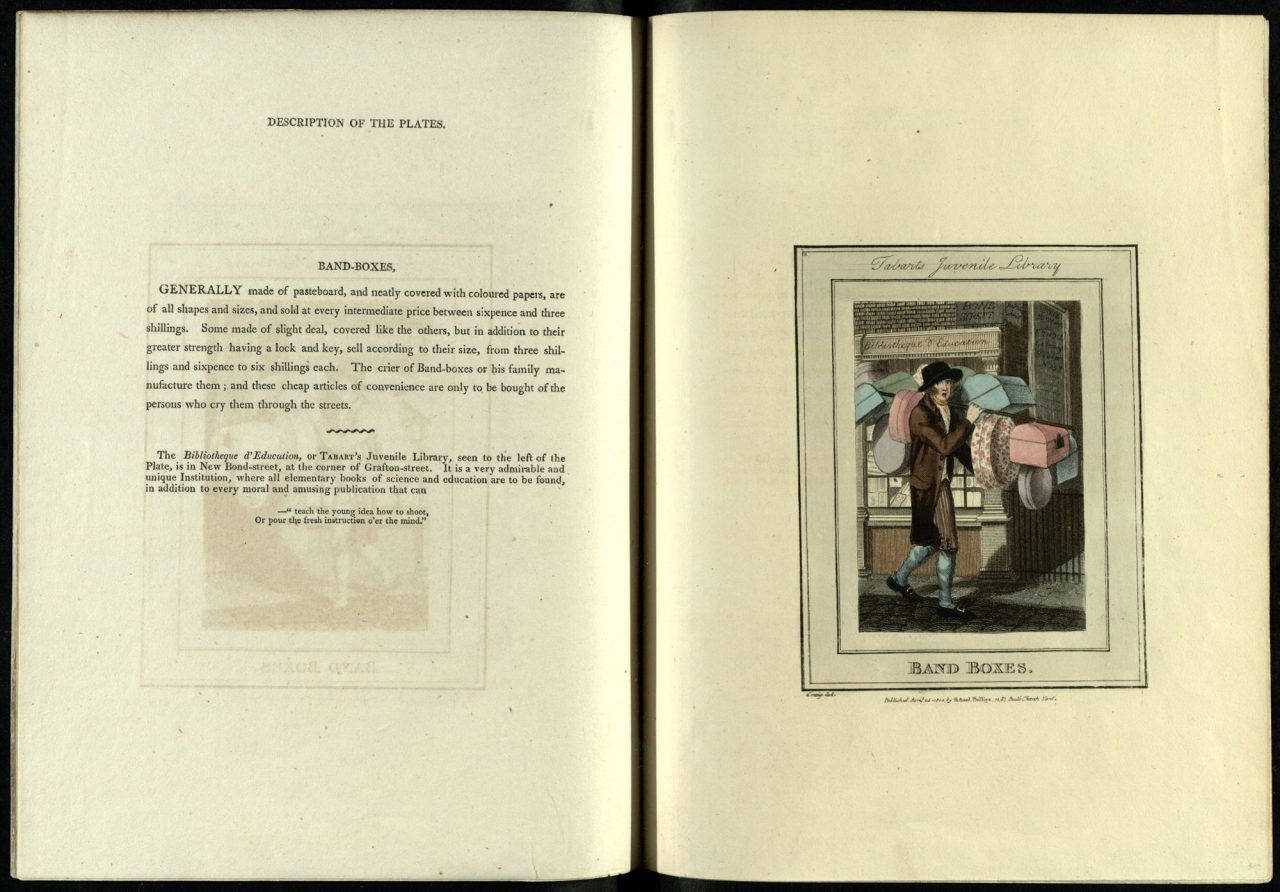

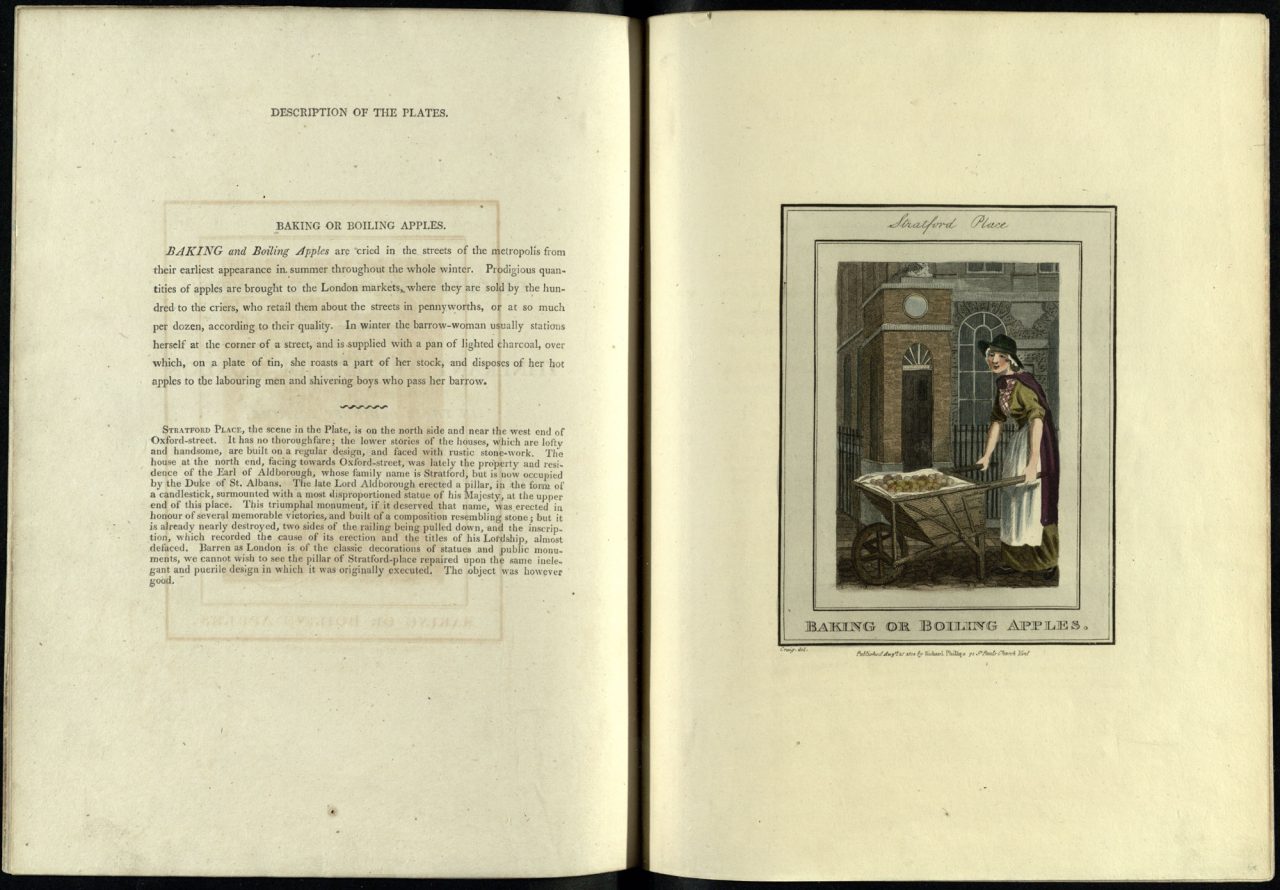

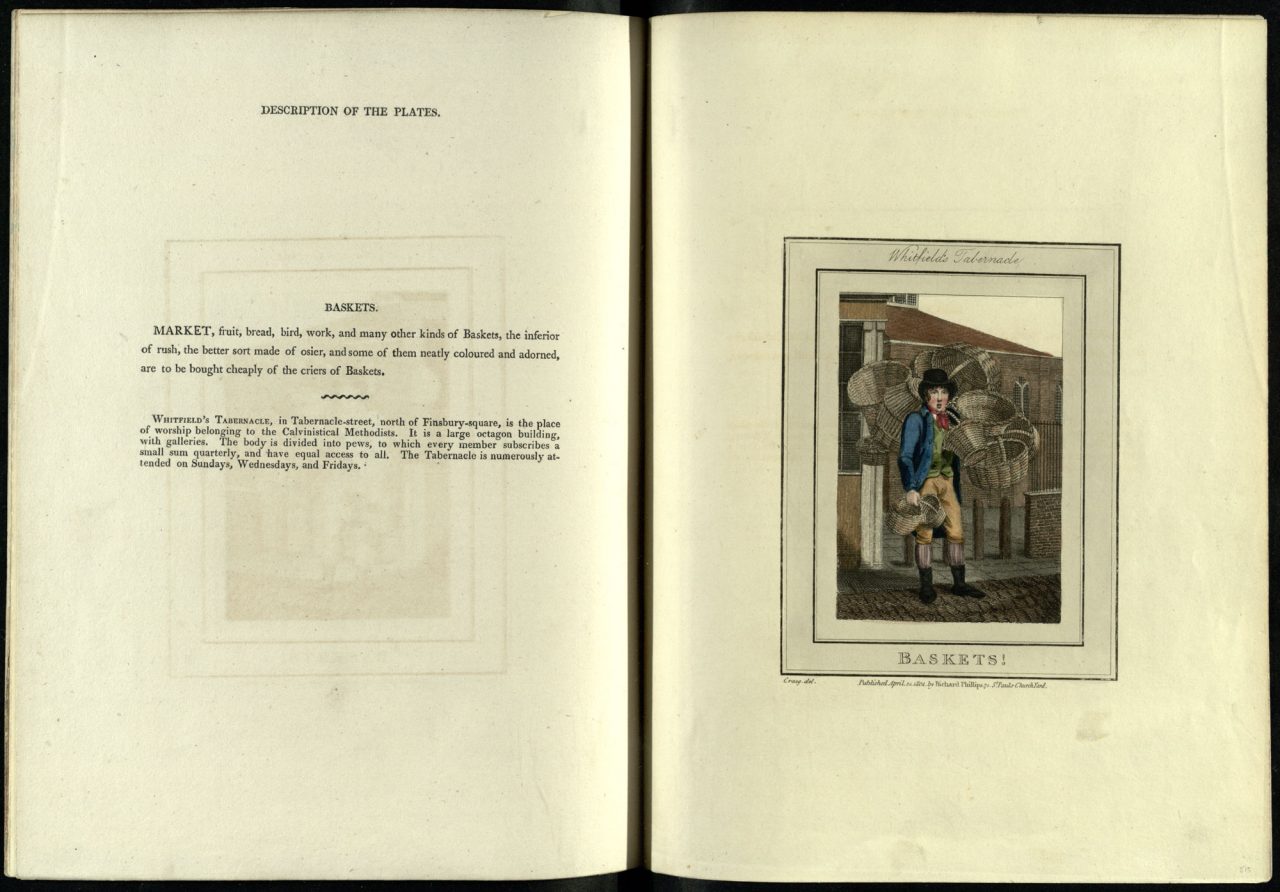

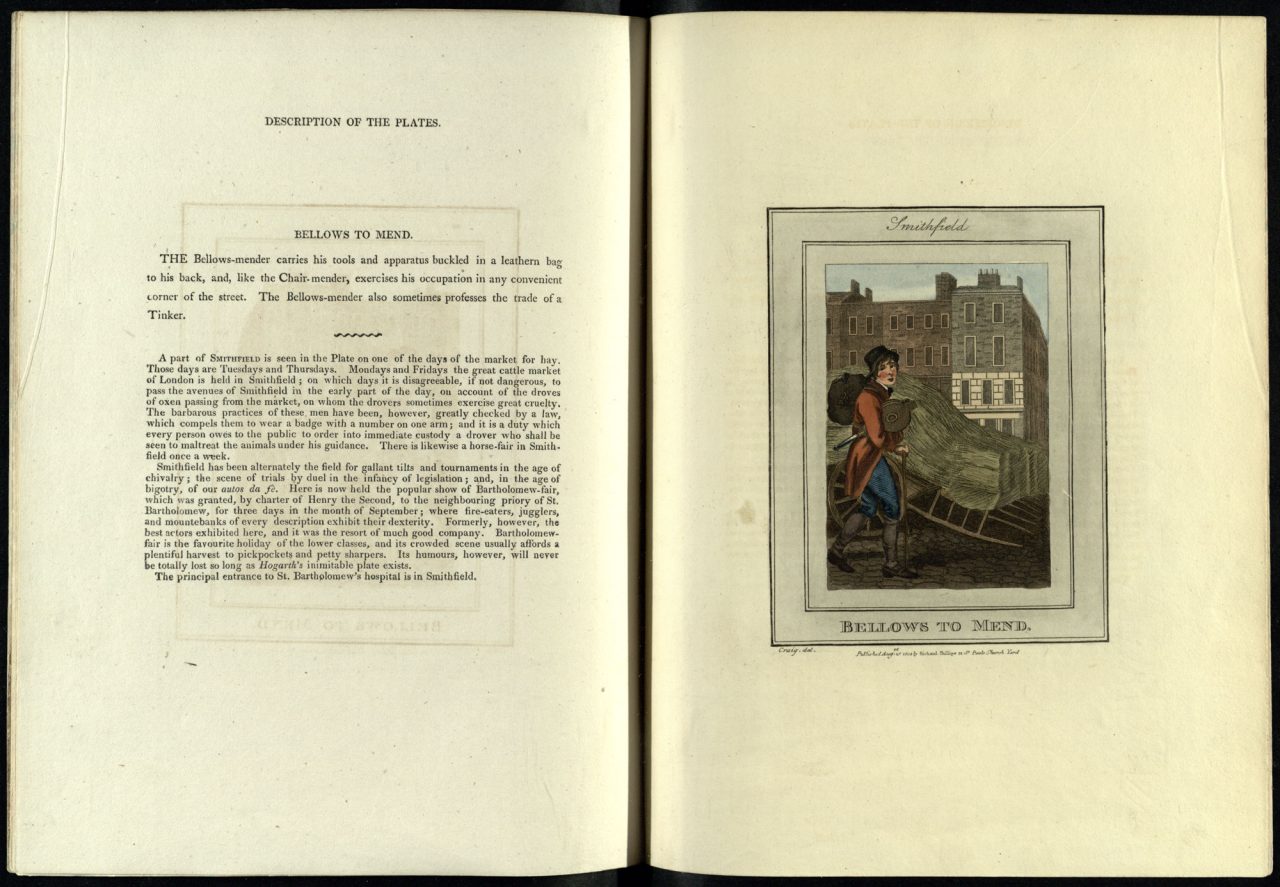

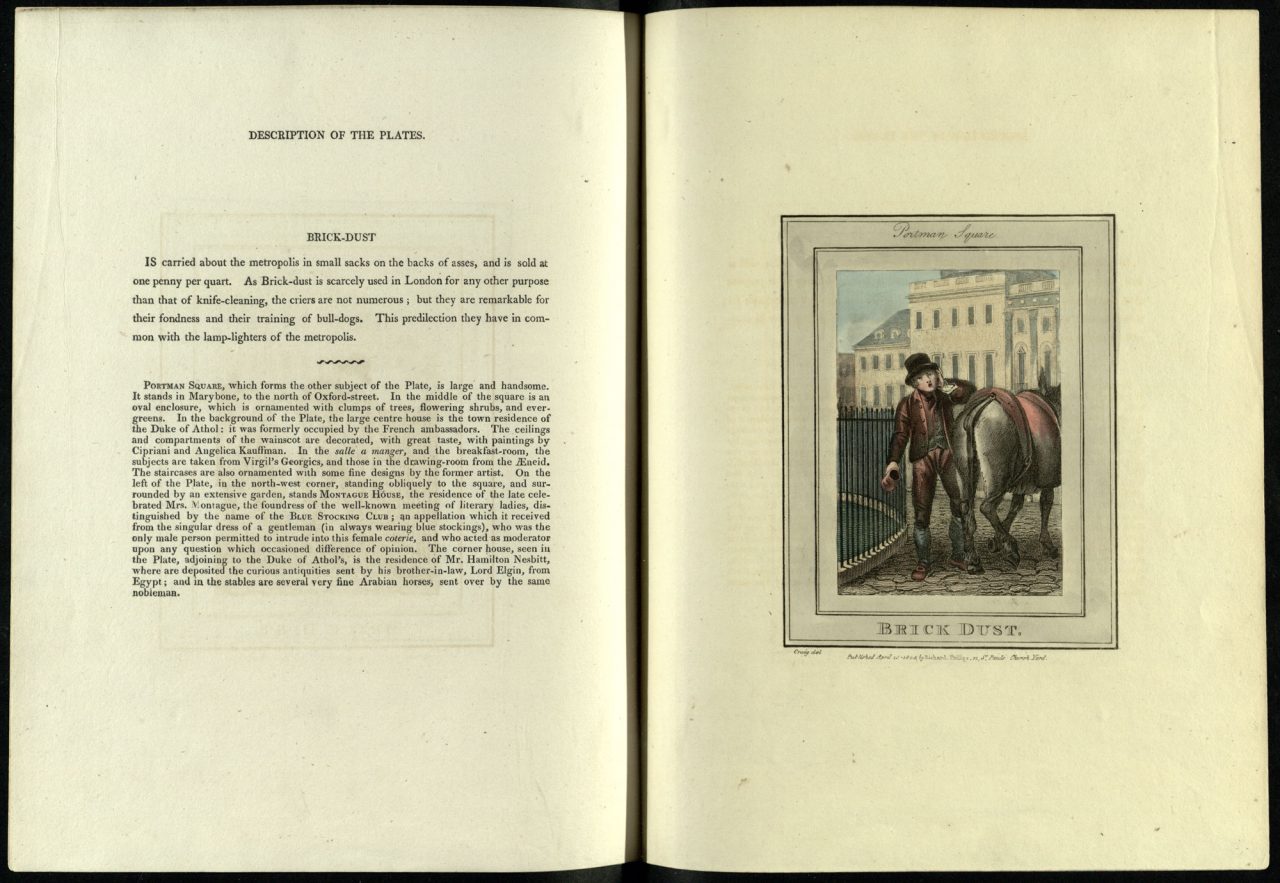

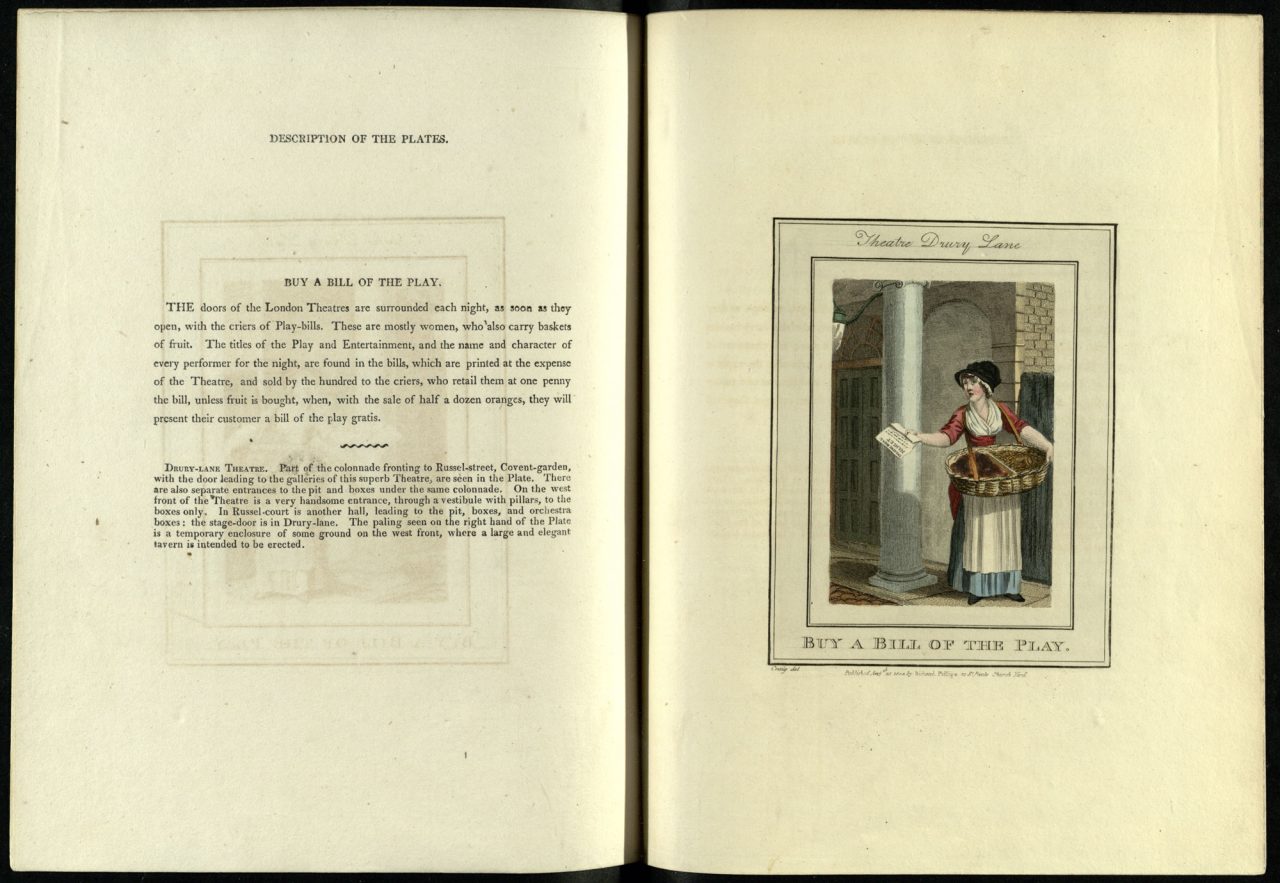

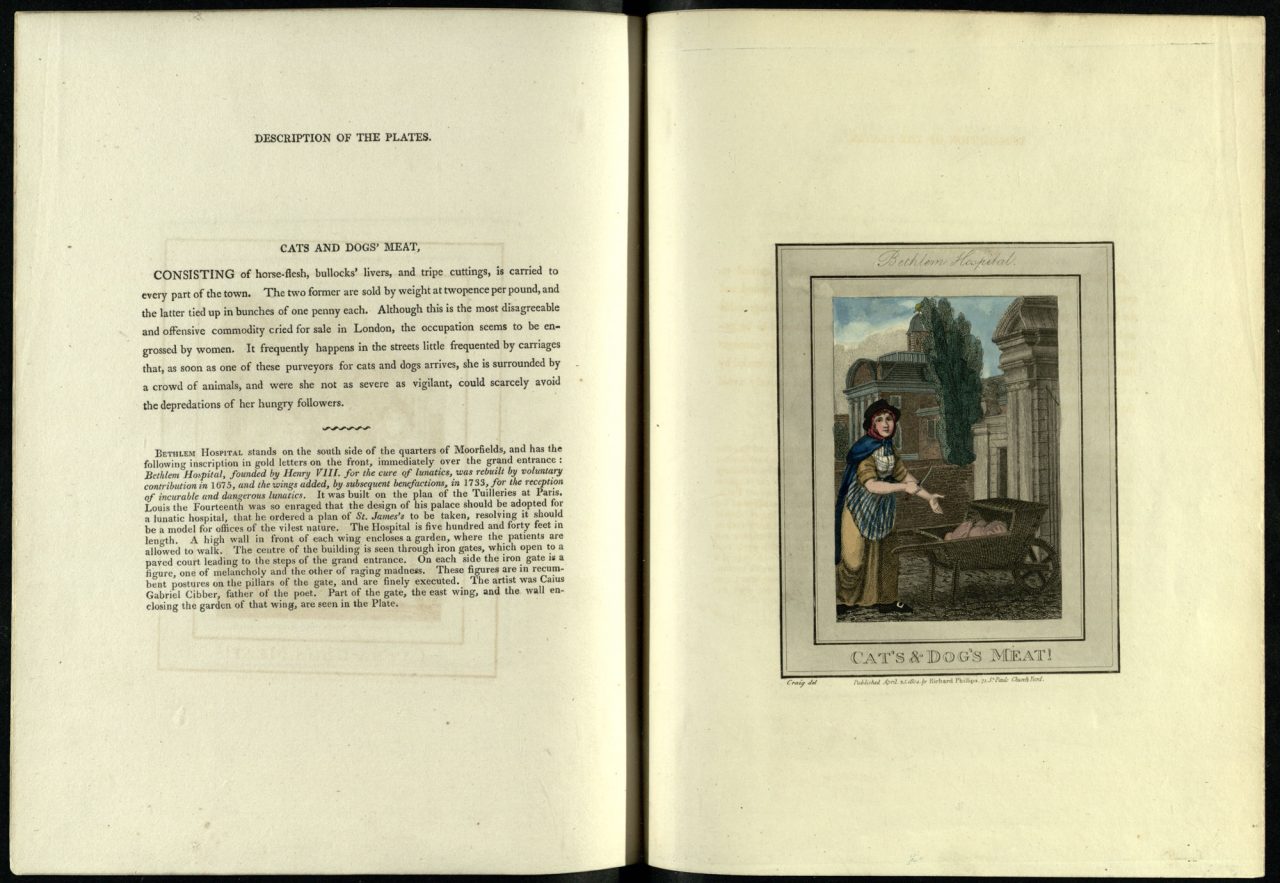

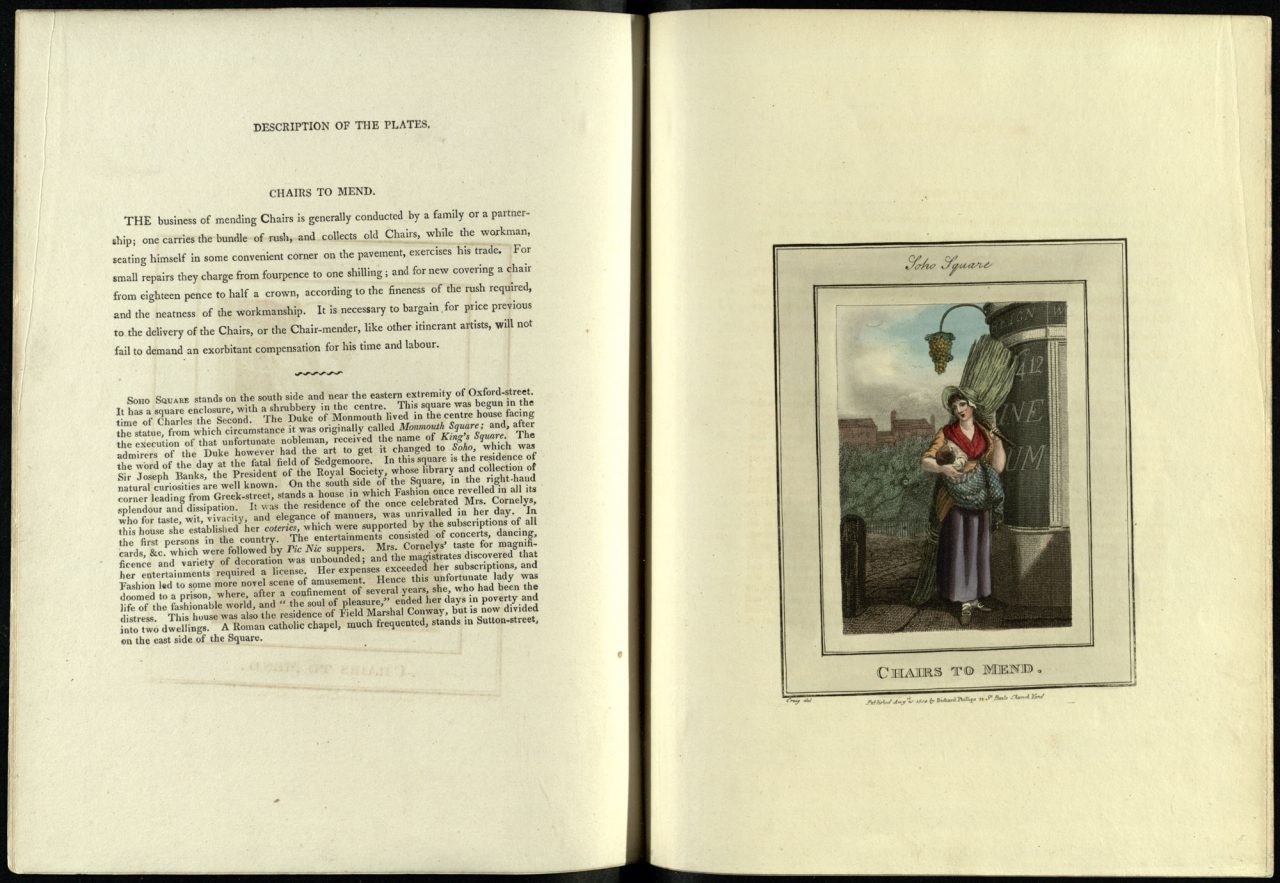

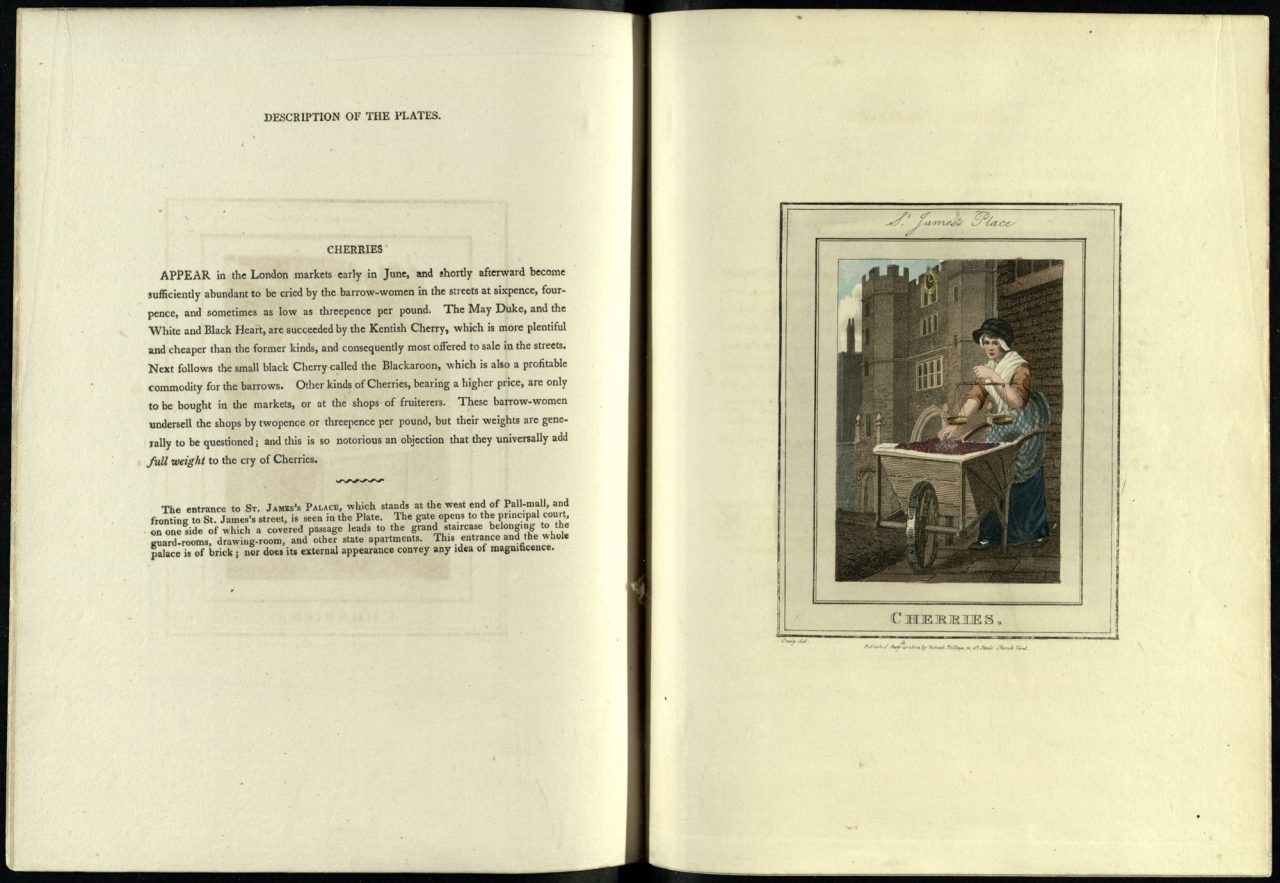

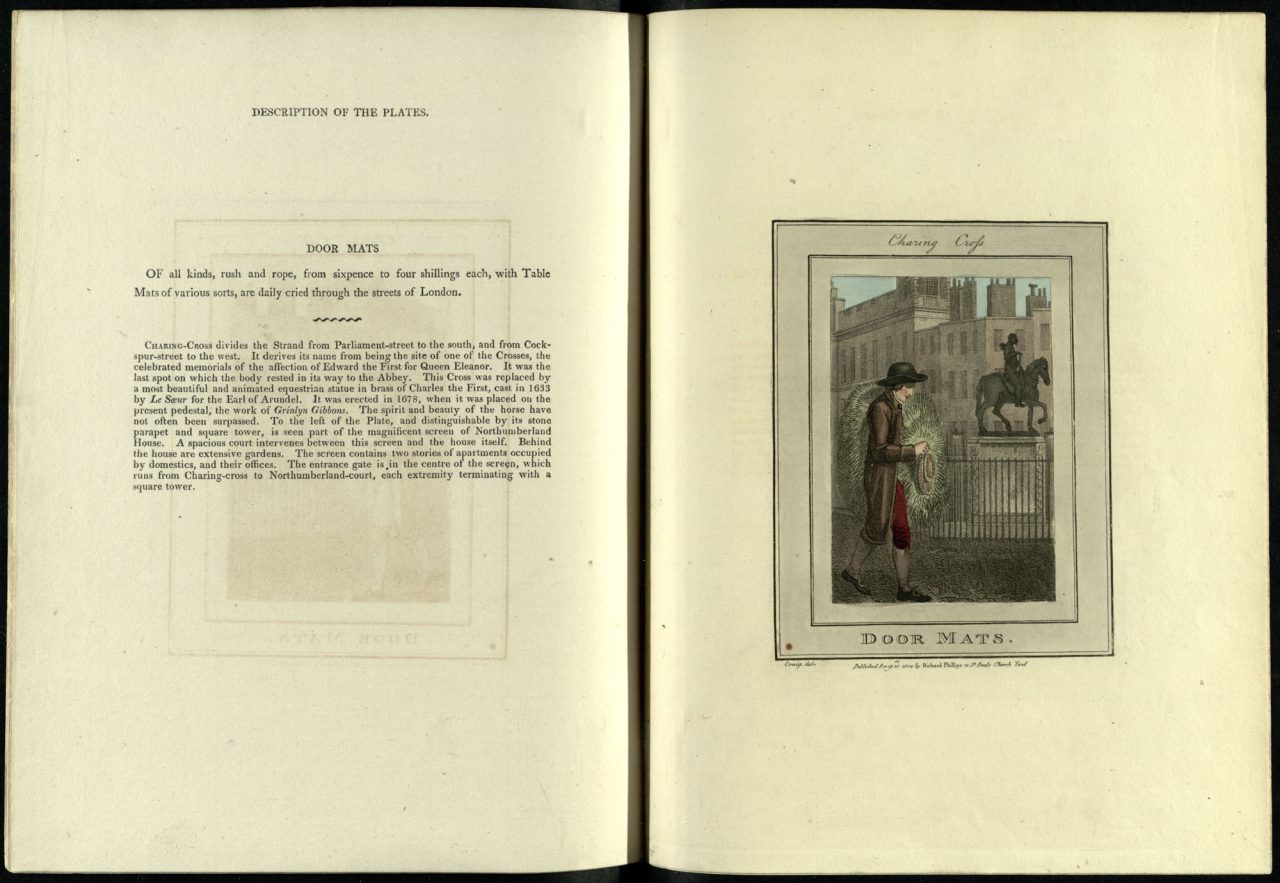

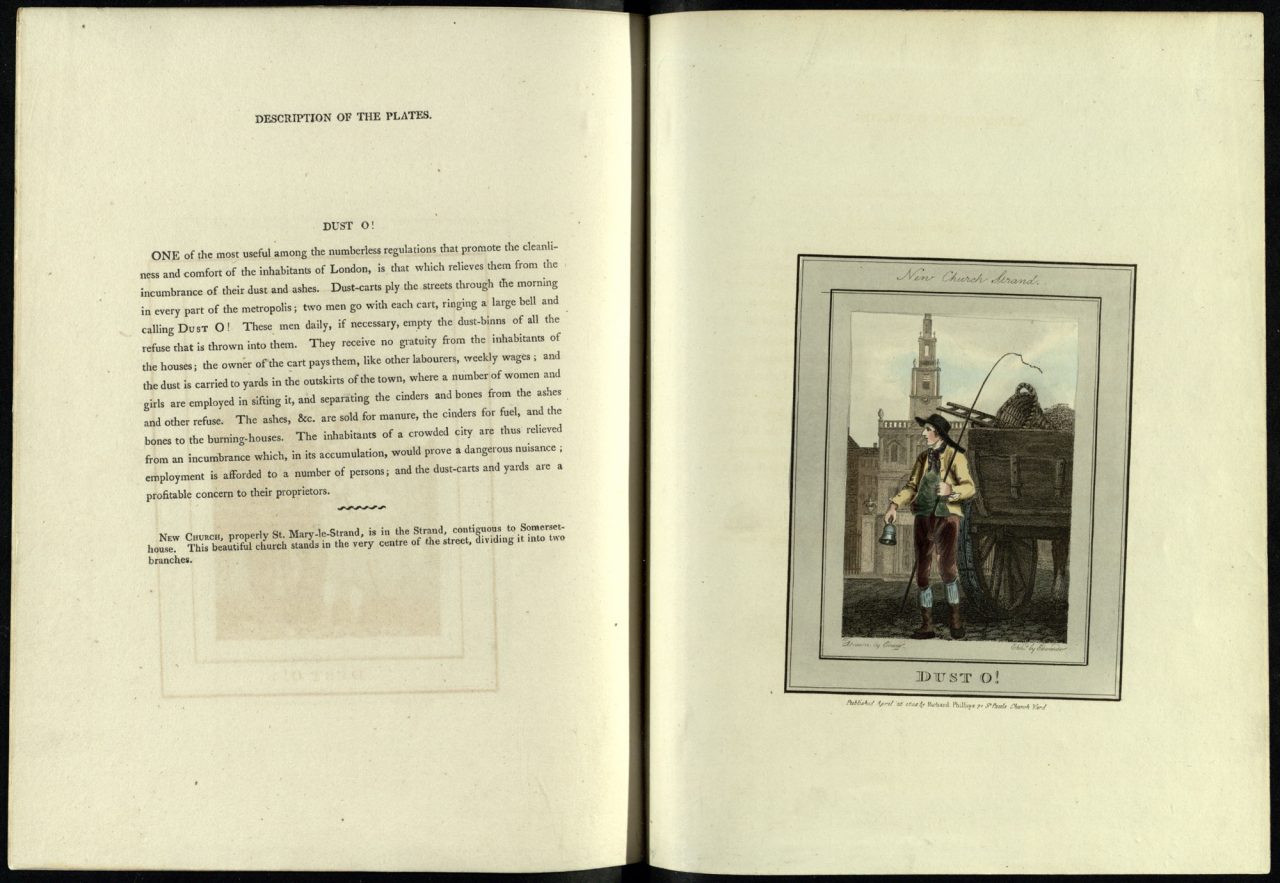

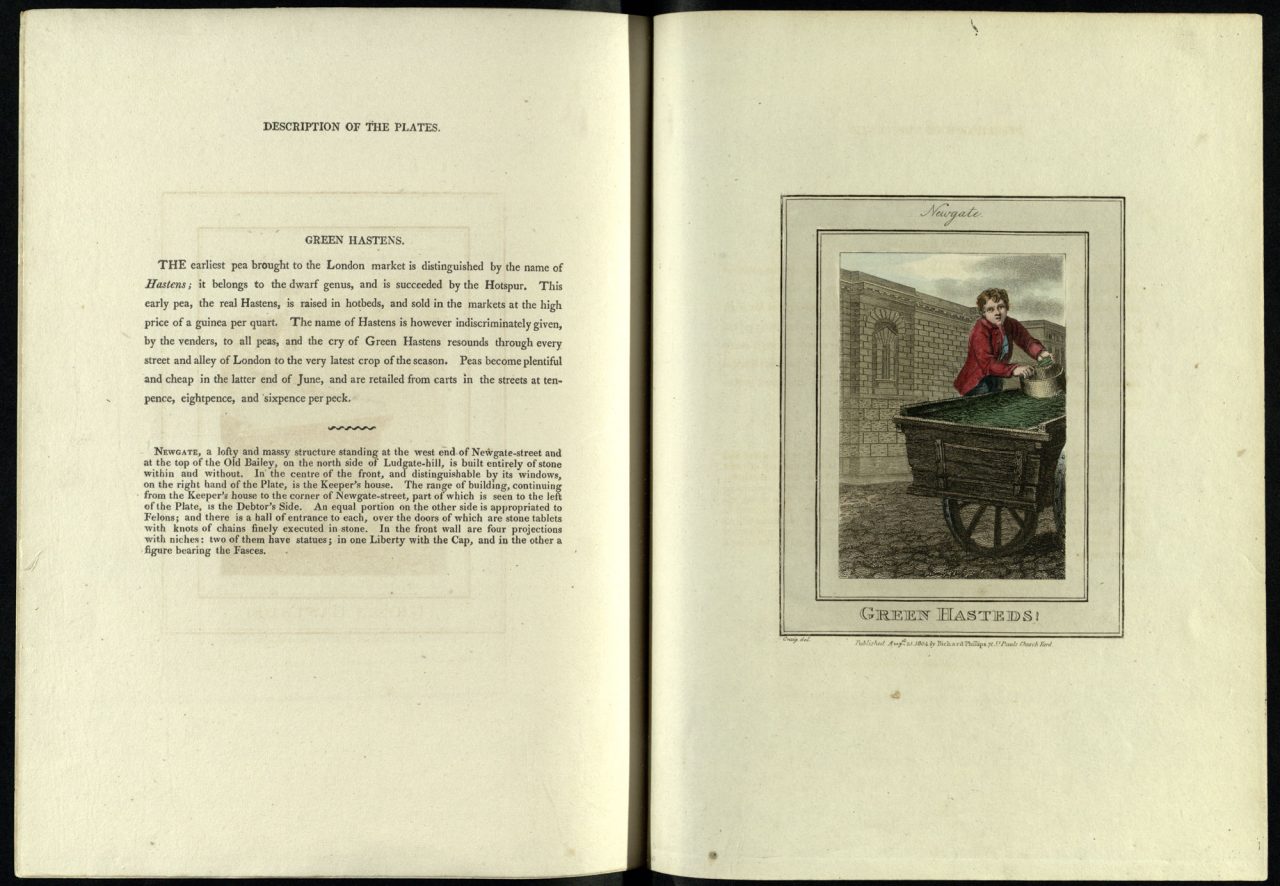

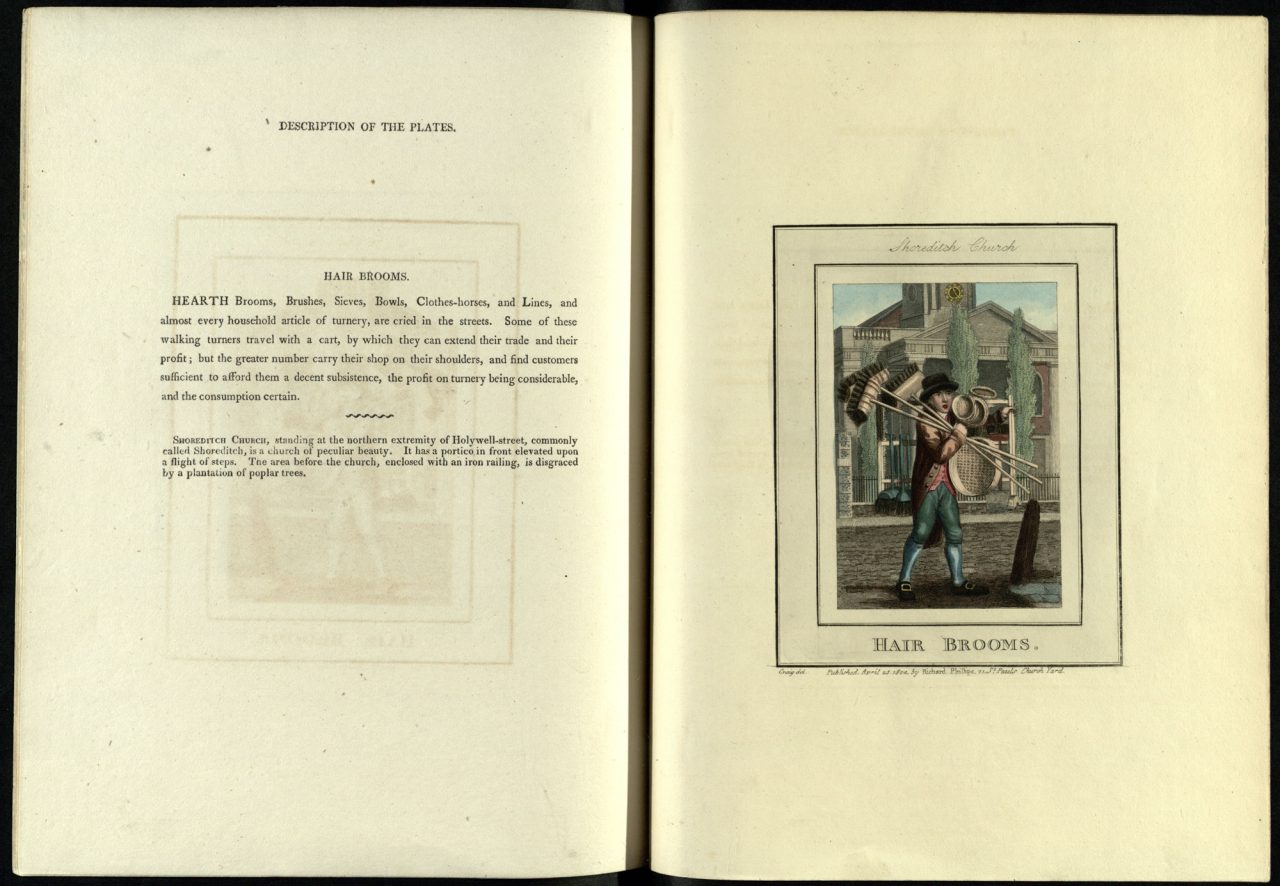

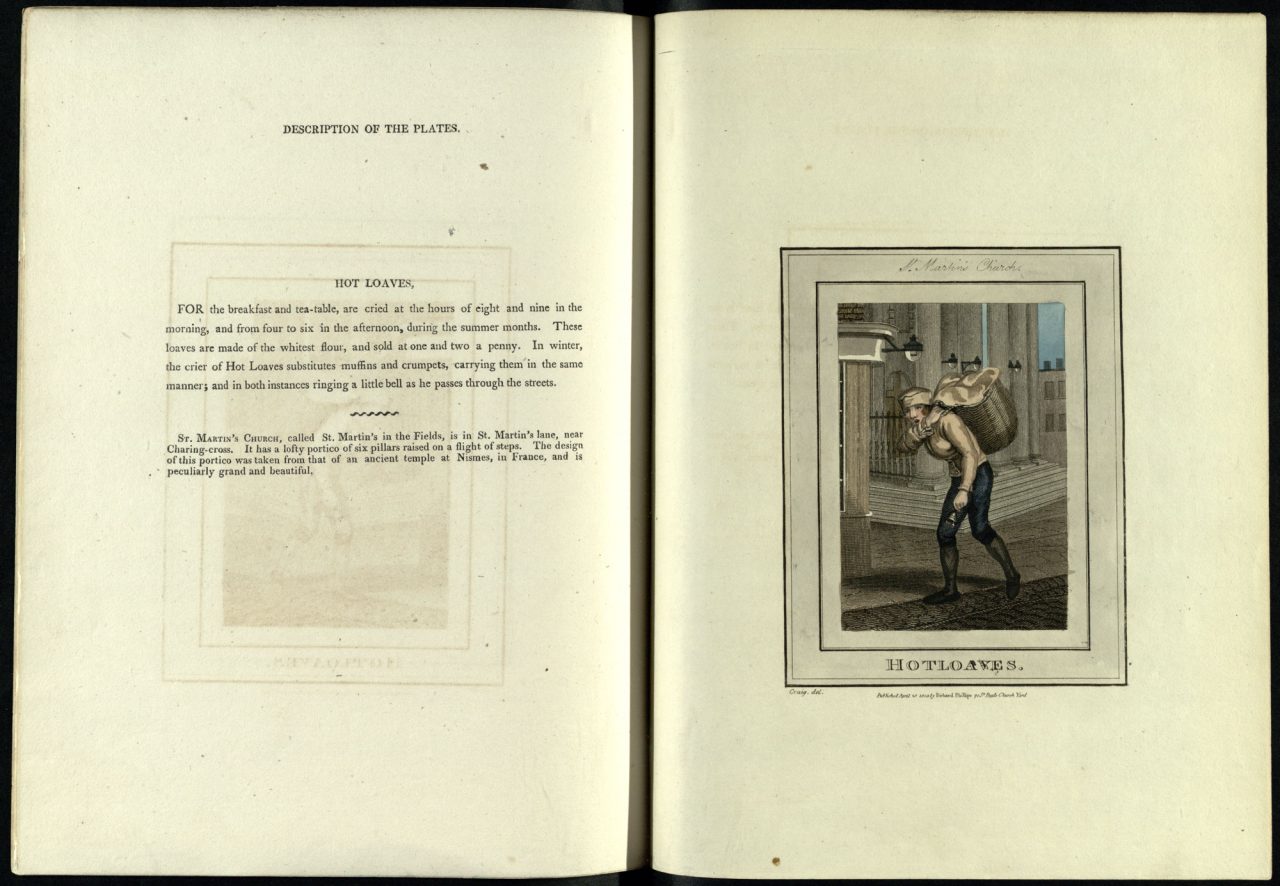

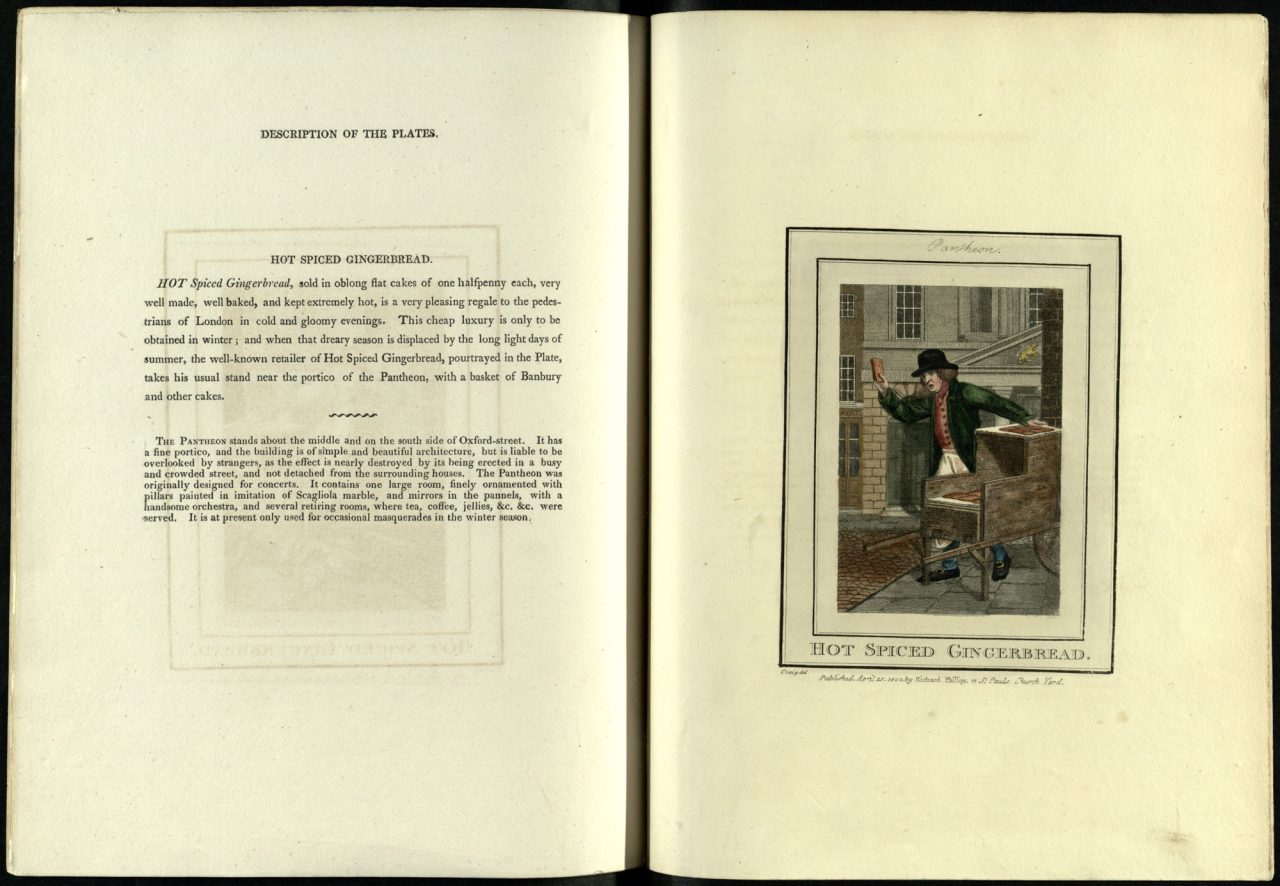

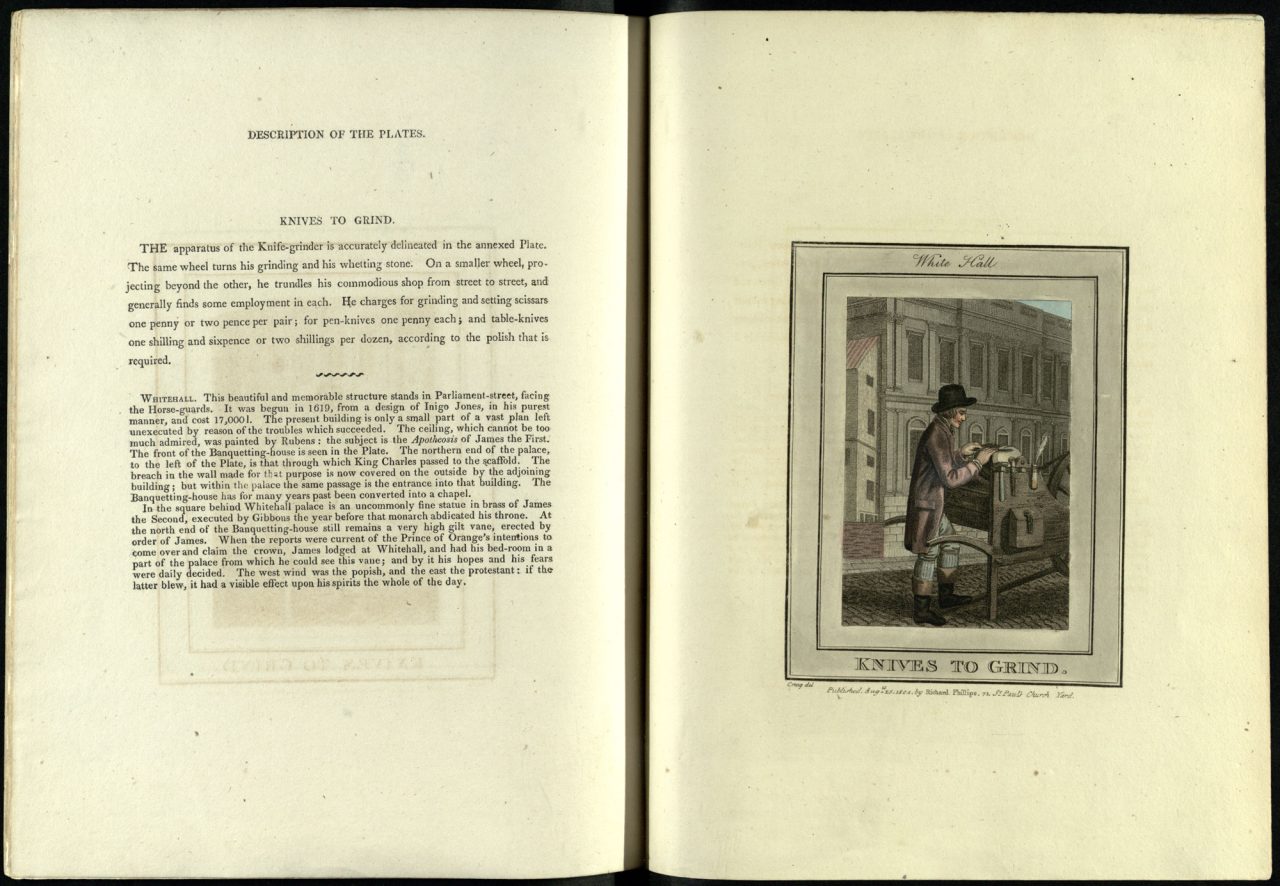

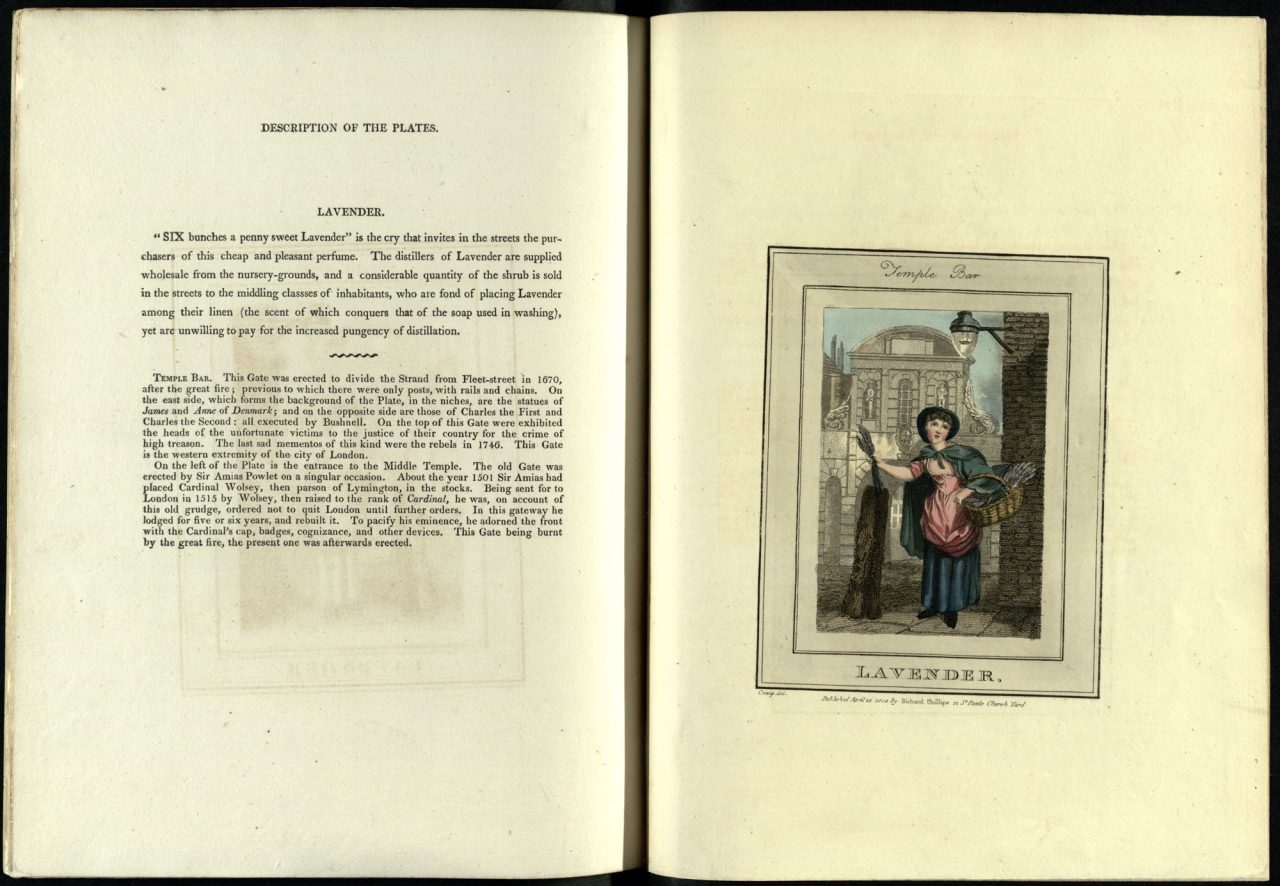

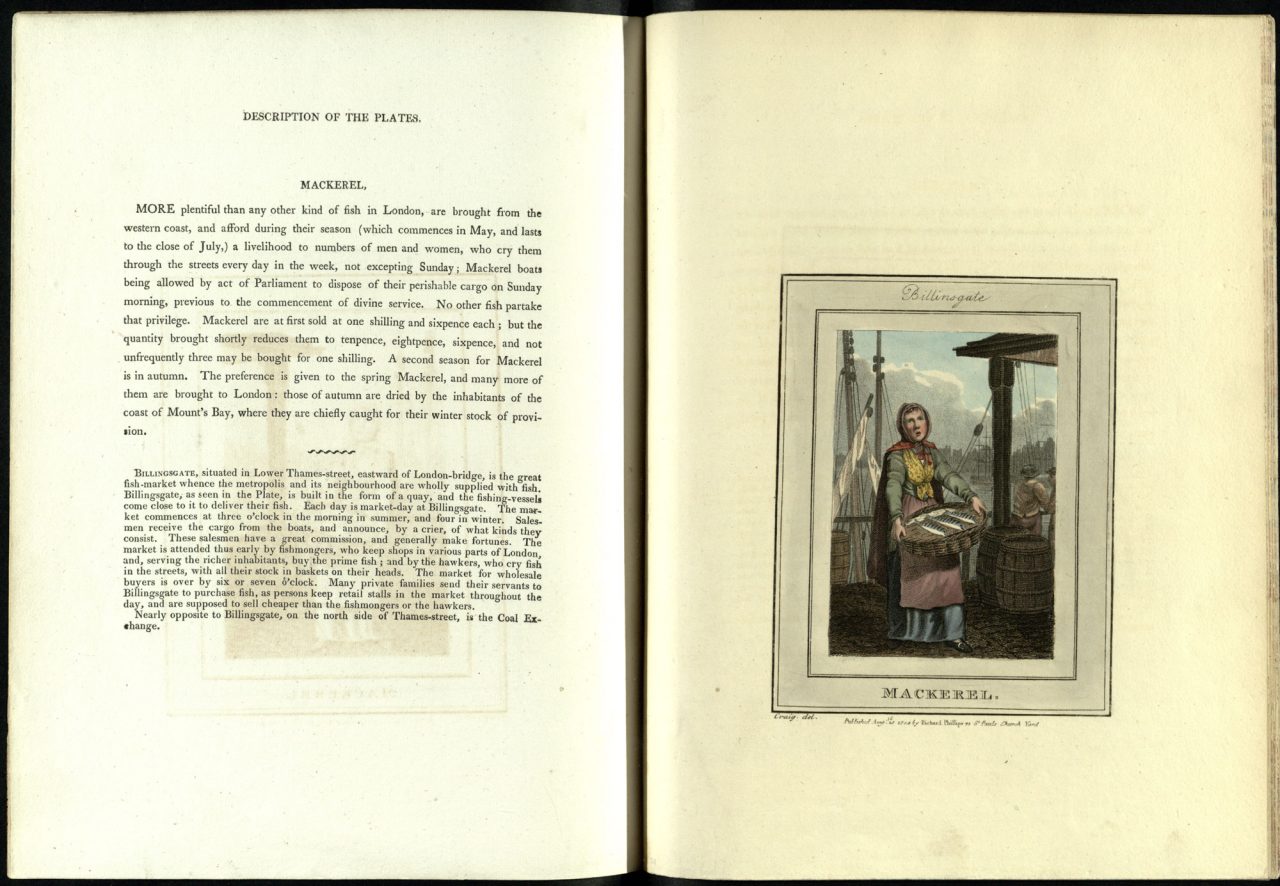

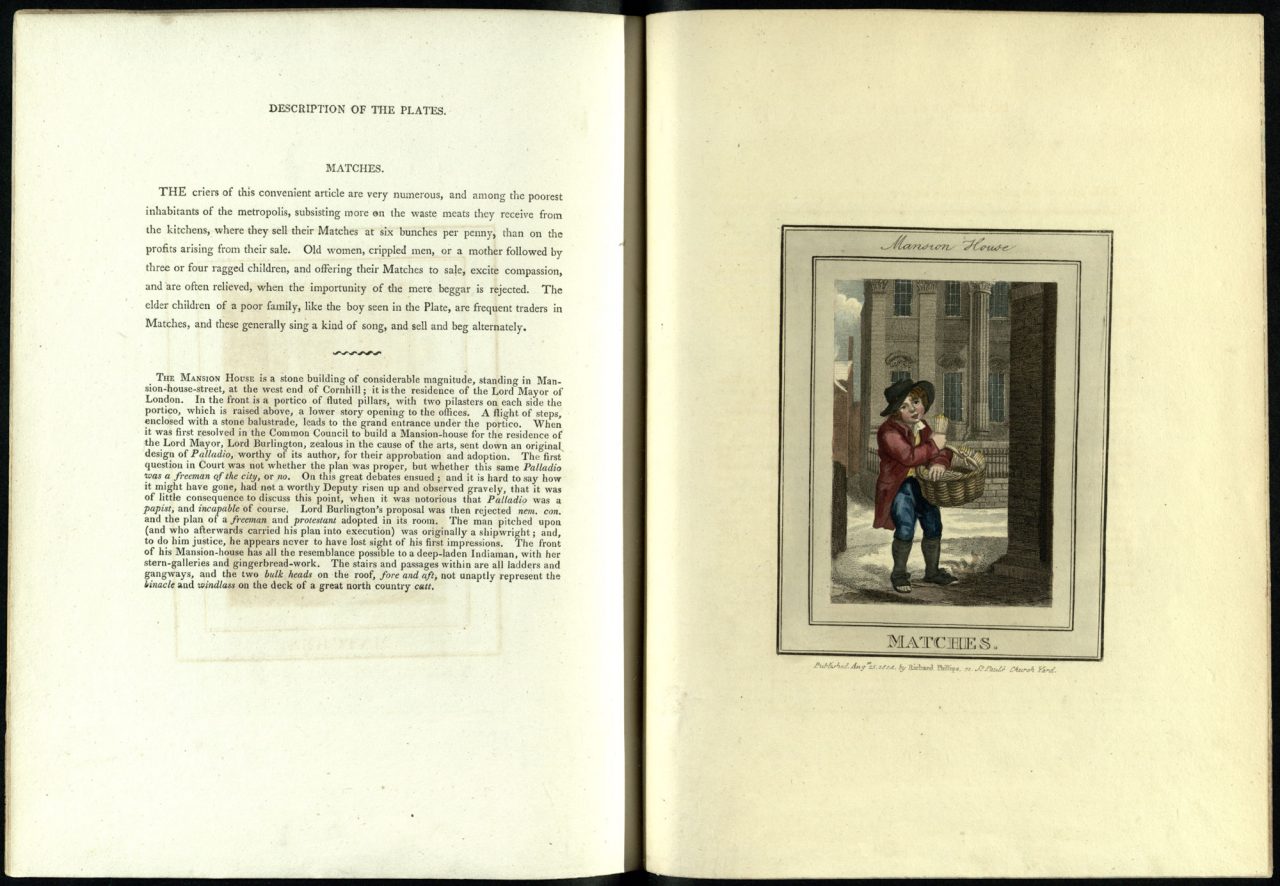

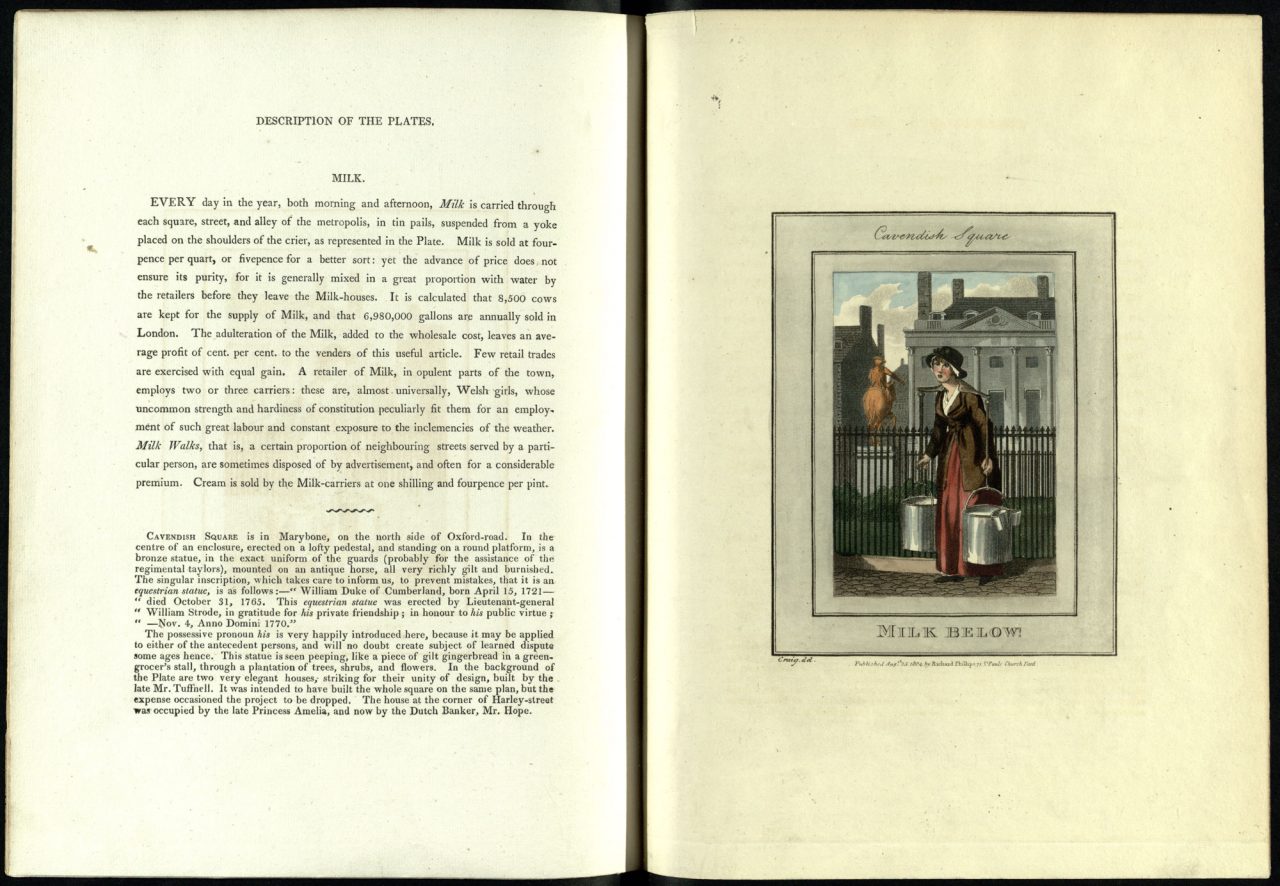

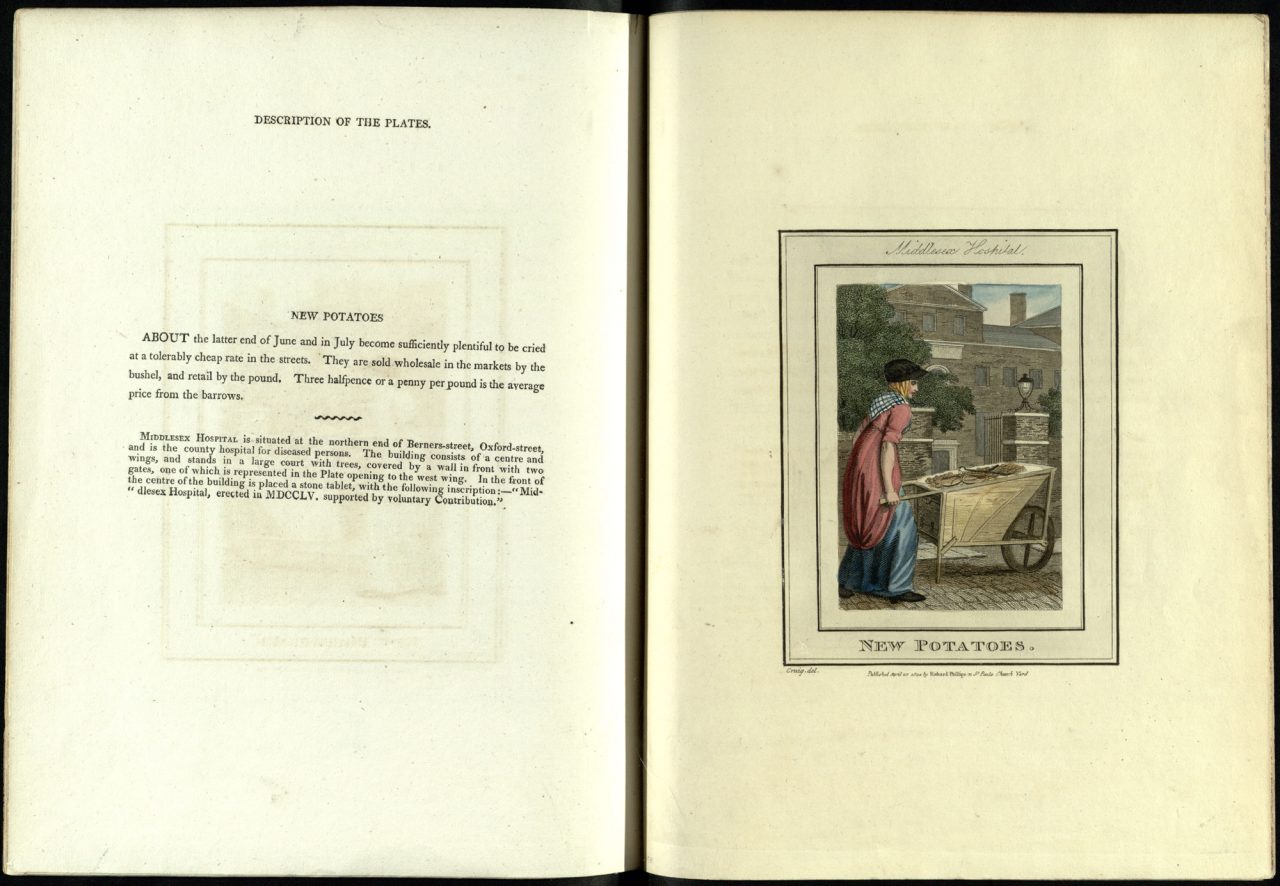

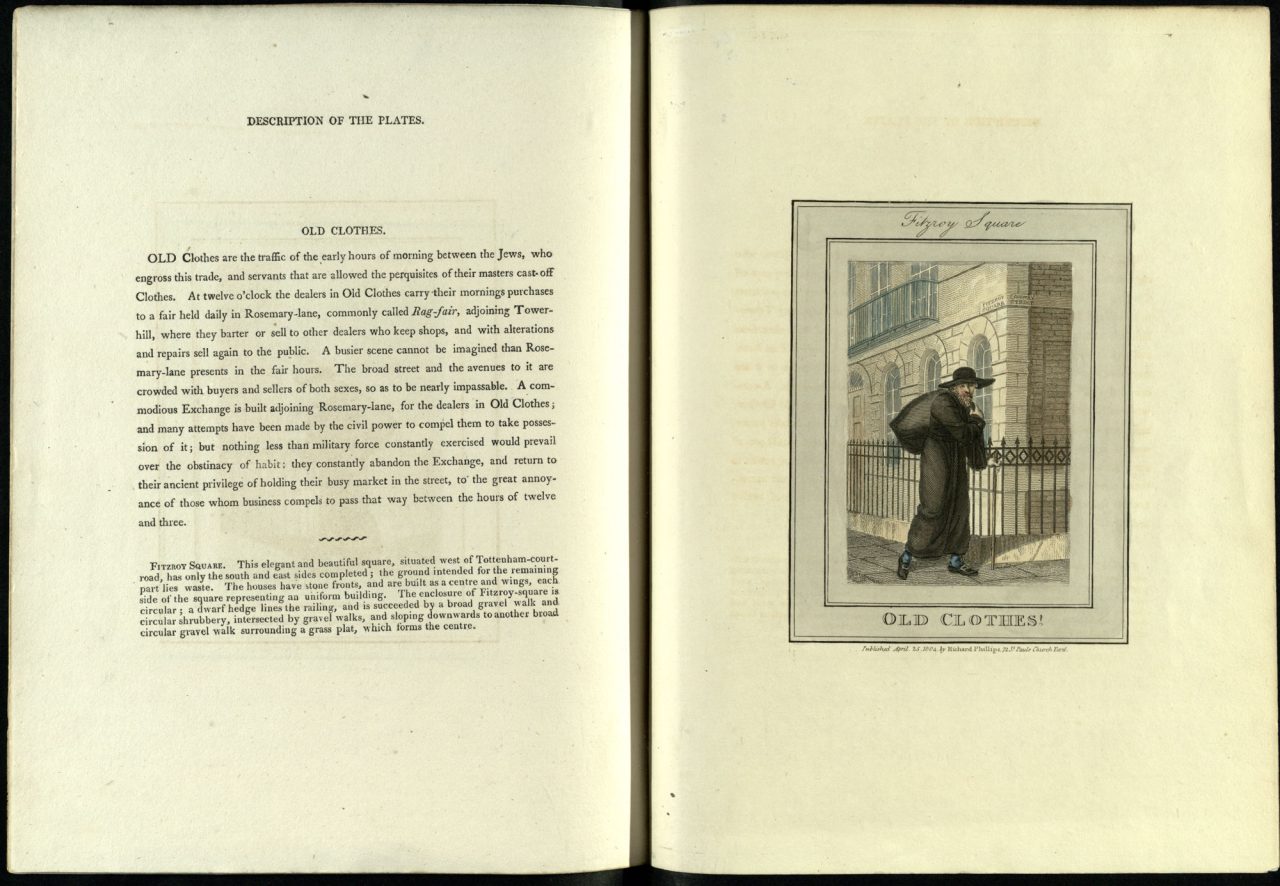

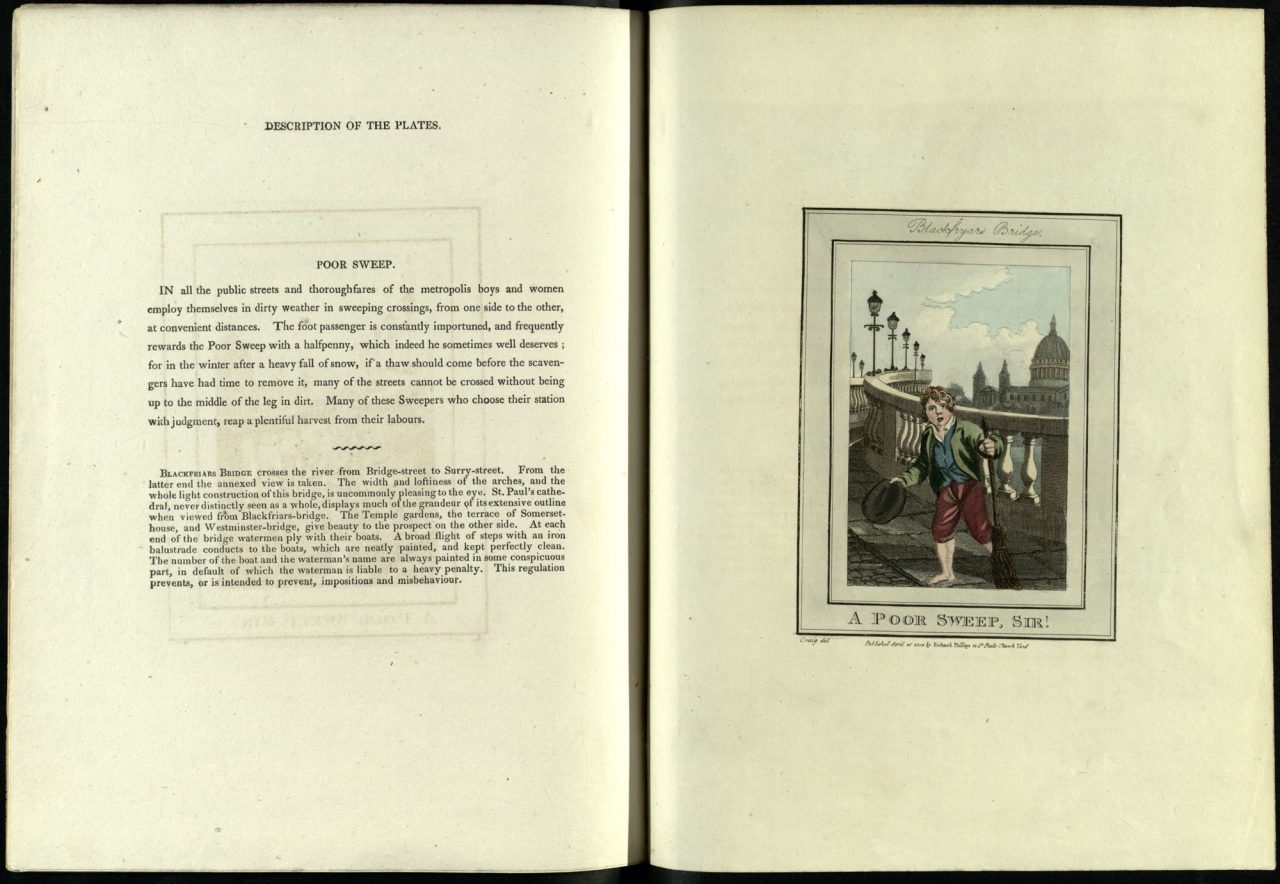

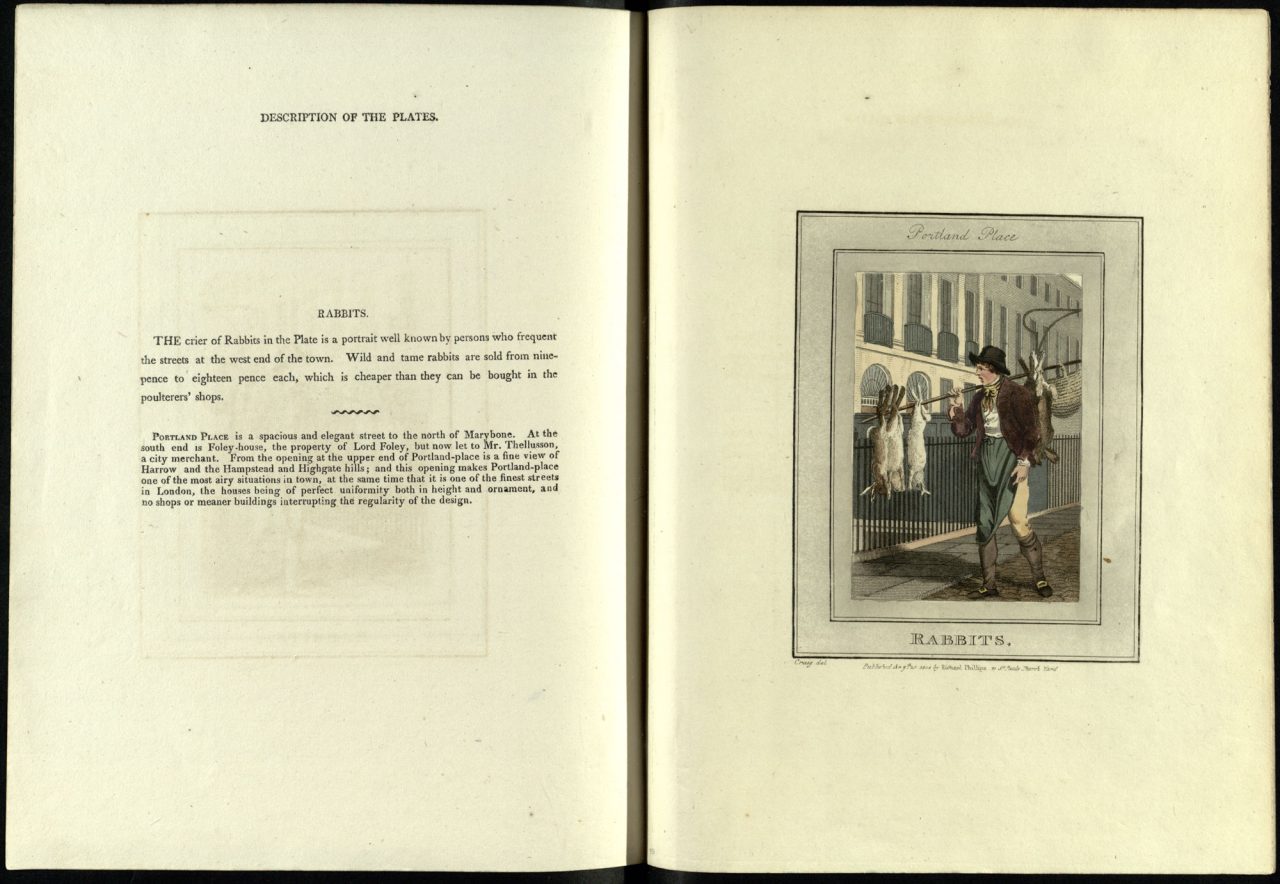

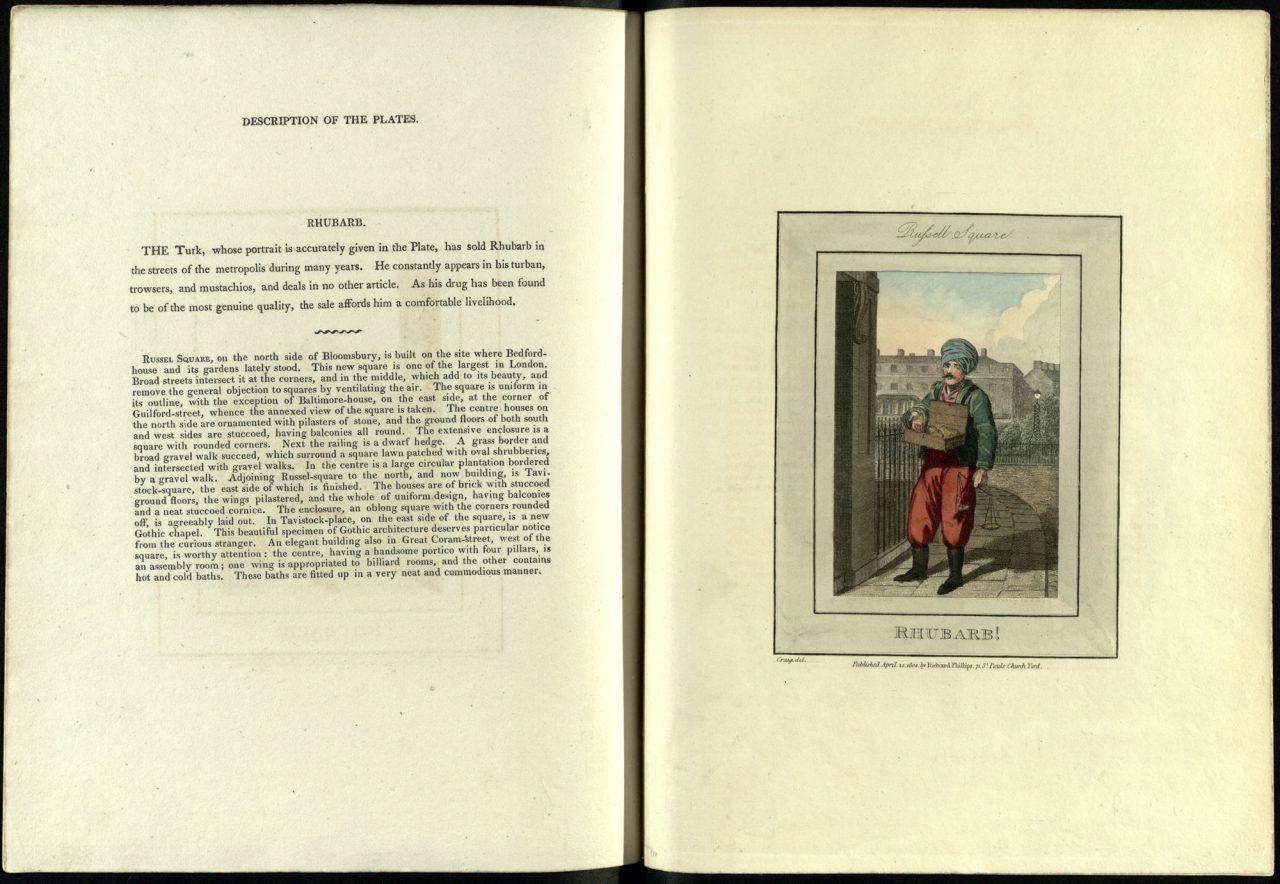

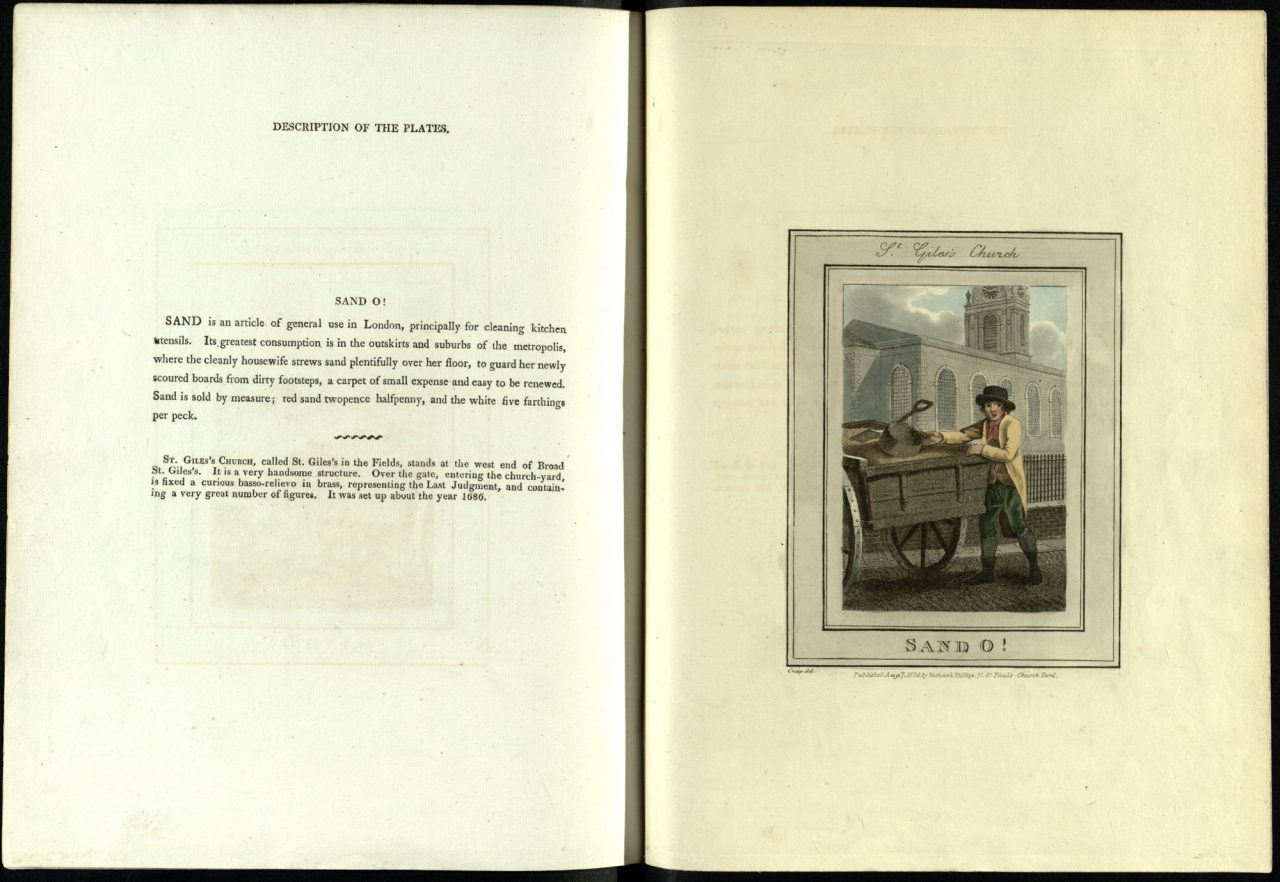

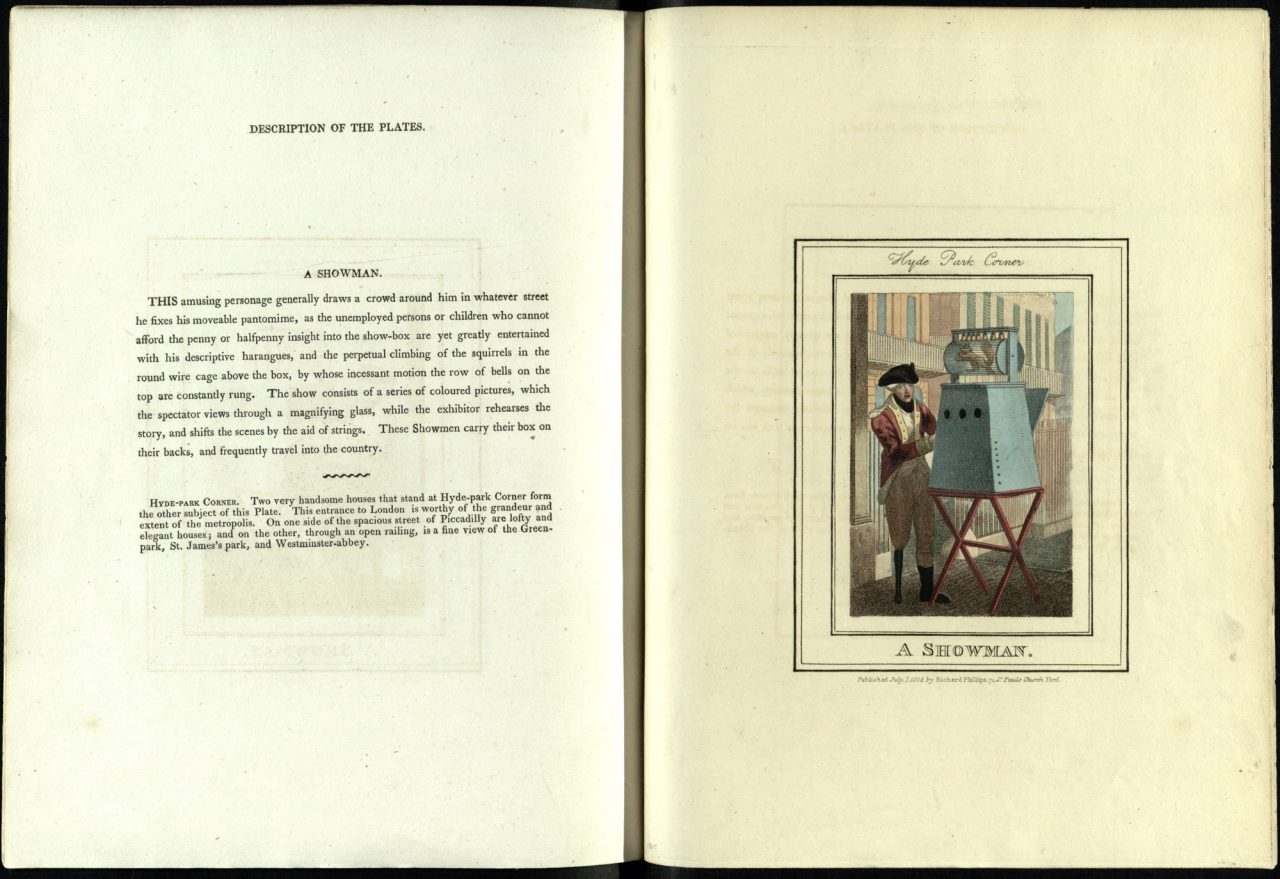

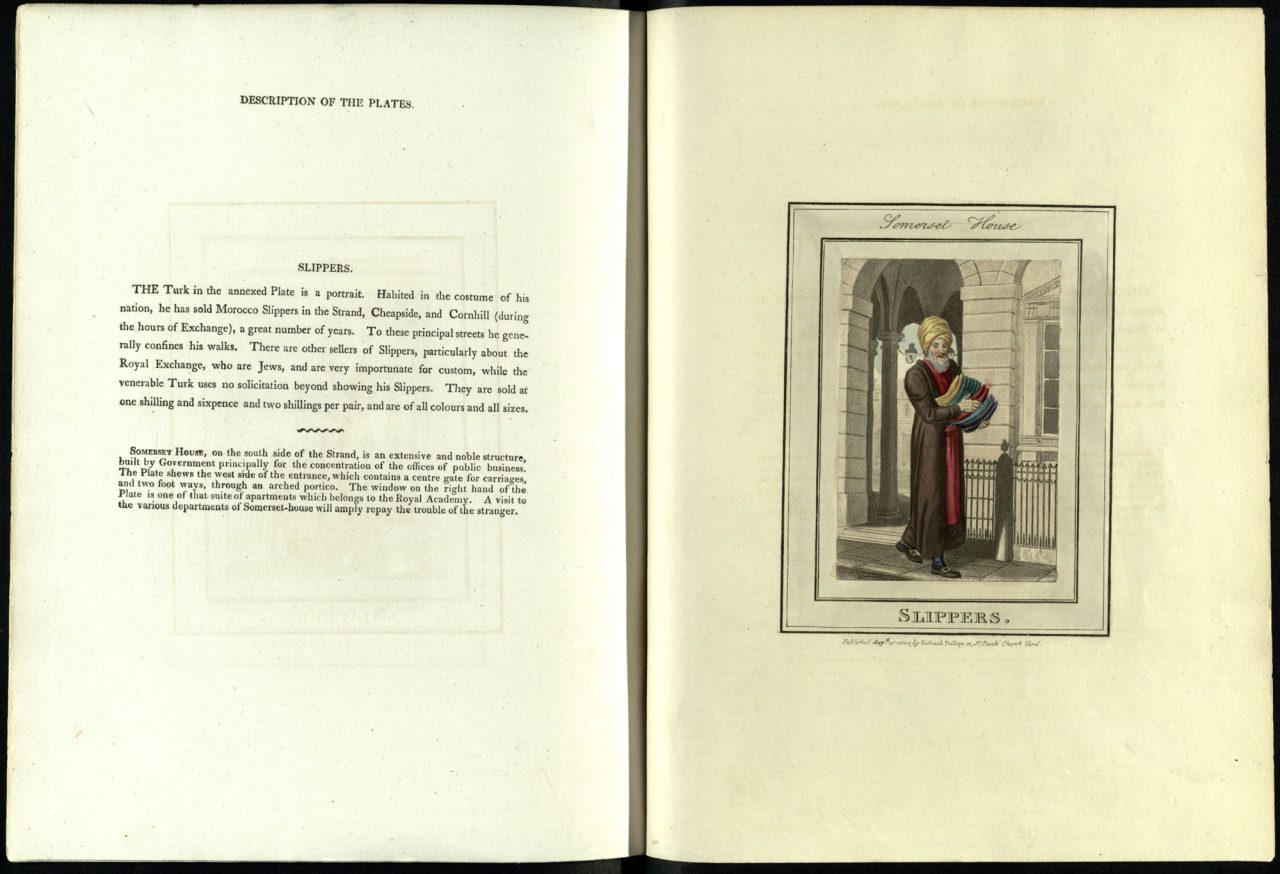

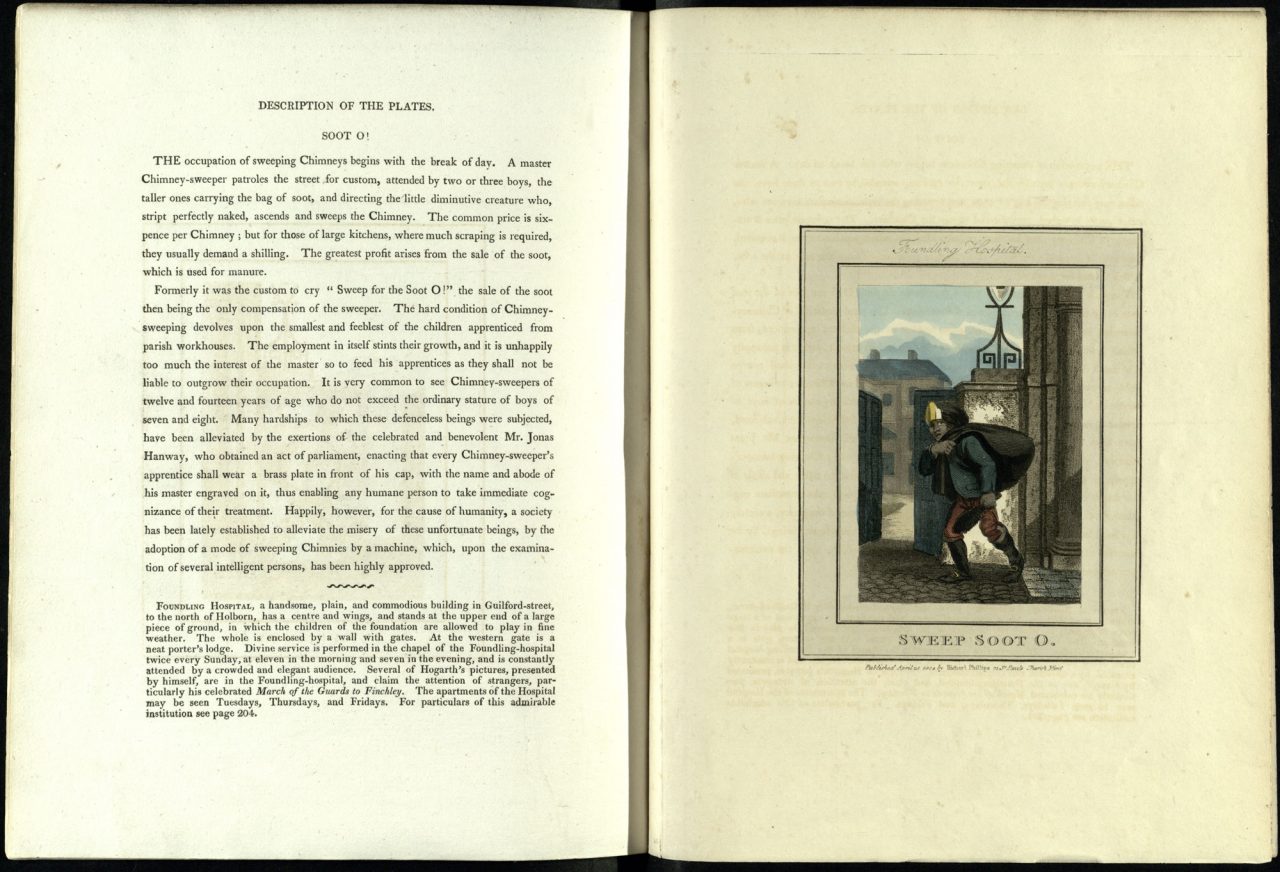

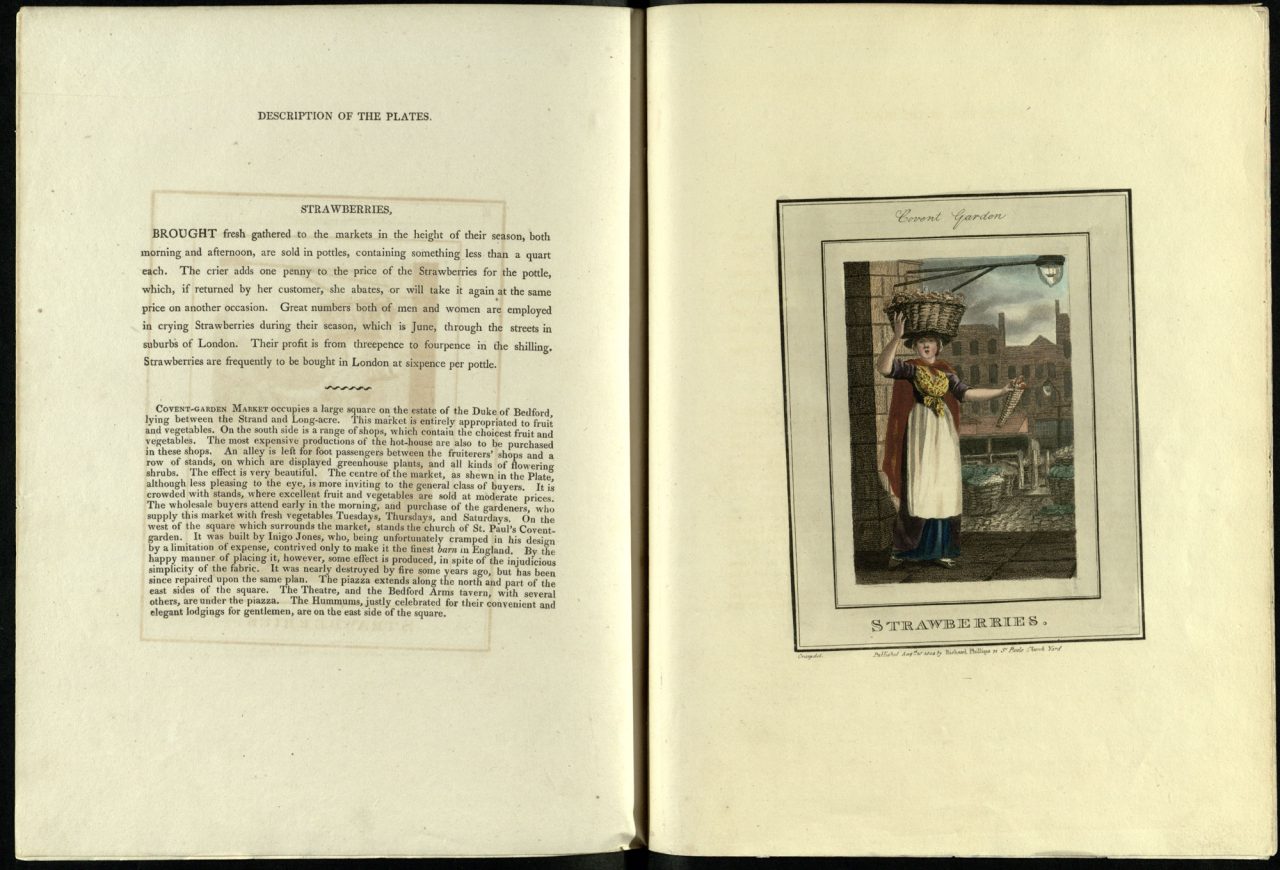

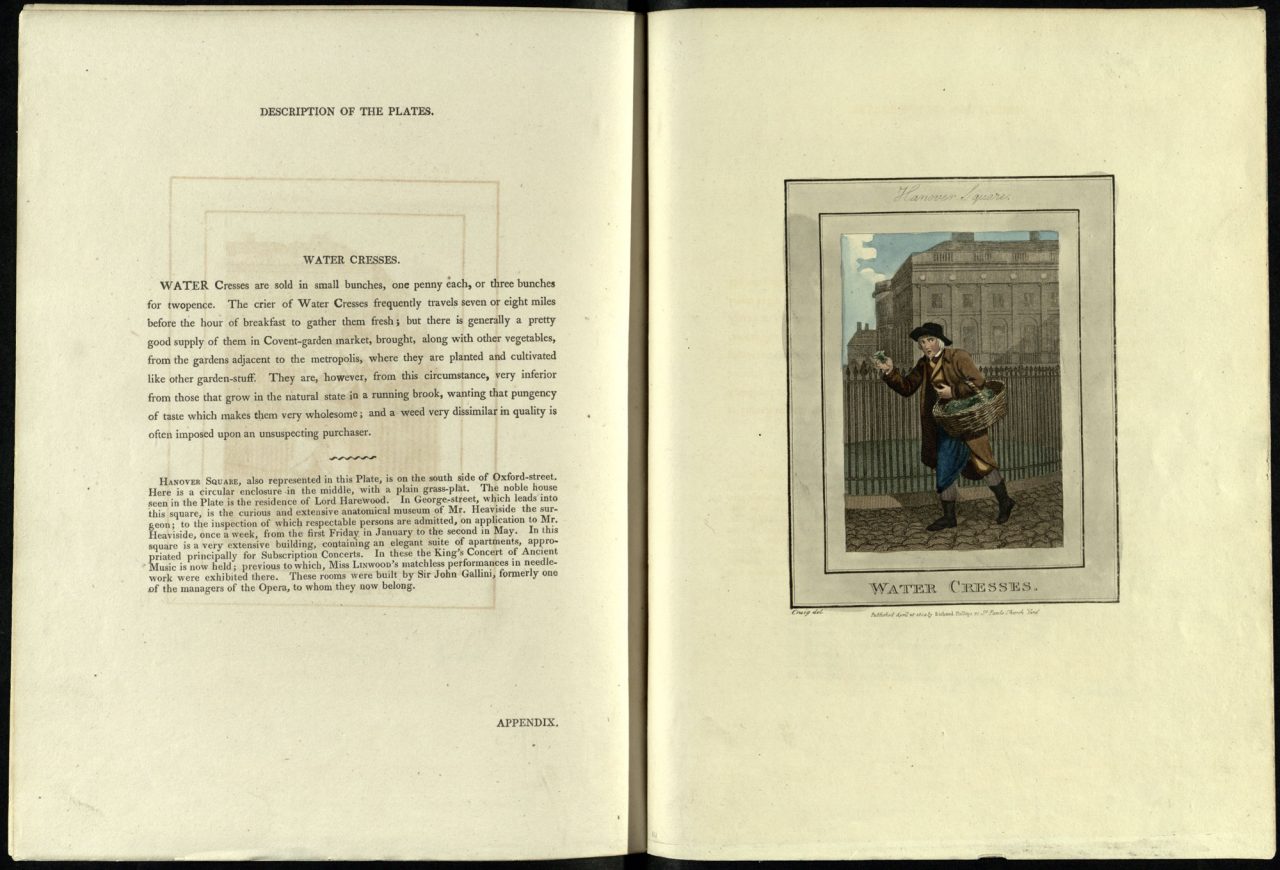

But even in poorer districts, dozens of shops competed with one another, and represented an important centre of social activity in most communities. Weekly markets in agricultural produce and livestock were also important events in most towns, alongside the daily bustle of peddlers and hawkers selling all manner of produce for a few pence: pastries, fish, fruit, vegetables and an array of household goods.

These advertisements for ready-to-eat street food reflect how food became part of the city scene for those who could afford it.

Depiction of a street seller offering colourful boxes, from William Craig’s Itinerant Traders of London, 1804.

Shop fronts were designed to attract the attention of passing trade and entice customers inside. Bow windows displaying goods, hanging signs, bright lights, mirrors and colourful trade advertisements all became standard features of retail early in the century.

The popularity of print shops in the early 19th century is illustrated here: prints were often bought and then shared amongst friends and relations.

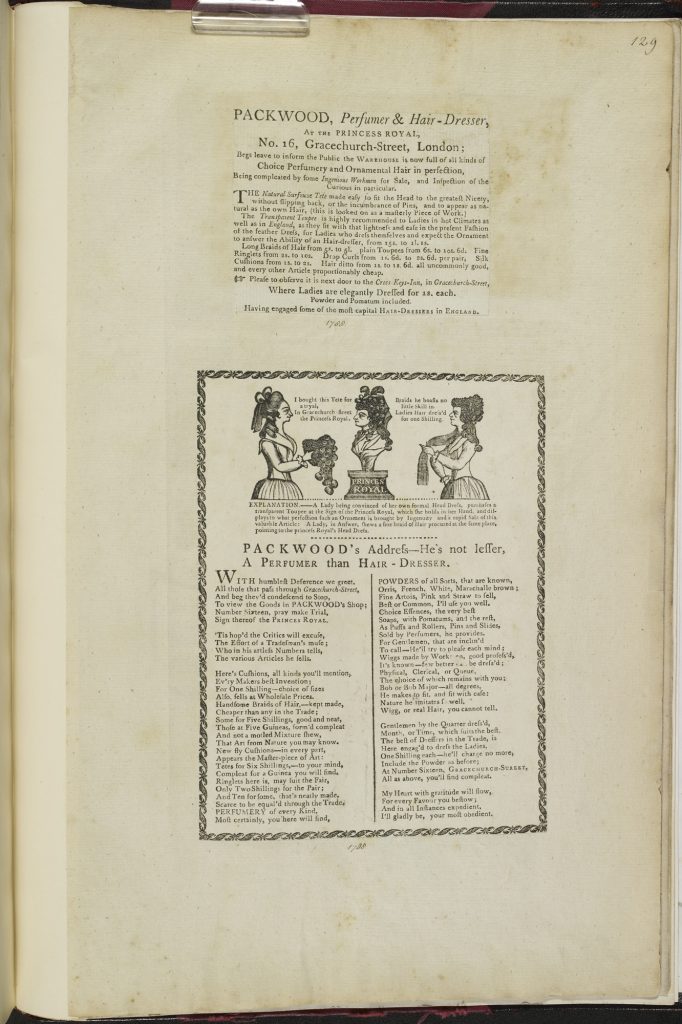

Many shops catered specifically to refined tastes, and shopping in them came to define one’s social status. Milliners, haberdashers, goldsmiths and furniture sellers, among others, all appealed to the latest tastes among the wealthy. One visitor to London at the end of the century described ‘a world of gold and silver plate, then pearls and gems shedding their dazzling lustre, home manufactures of the most exquisite taste, an ocean of rings, watches, chains, bracelets, perfumes, ready-dresses, ribbons, lace, bonnets, and fruits from all the zones of the habitable world’.

Hairdressing, styling and elite fashion developed in the second half of the 18th century as shown in this advertisement for Packwookd’s ‘Perfumer and Hair-Dresser’, 1788.

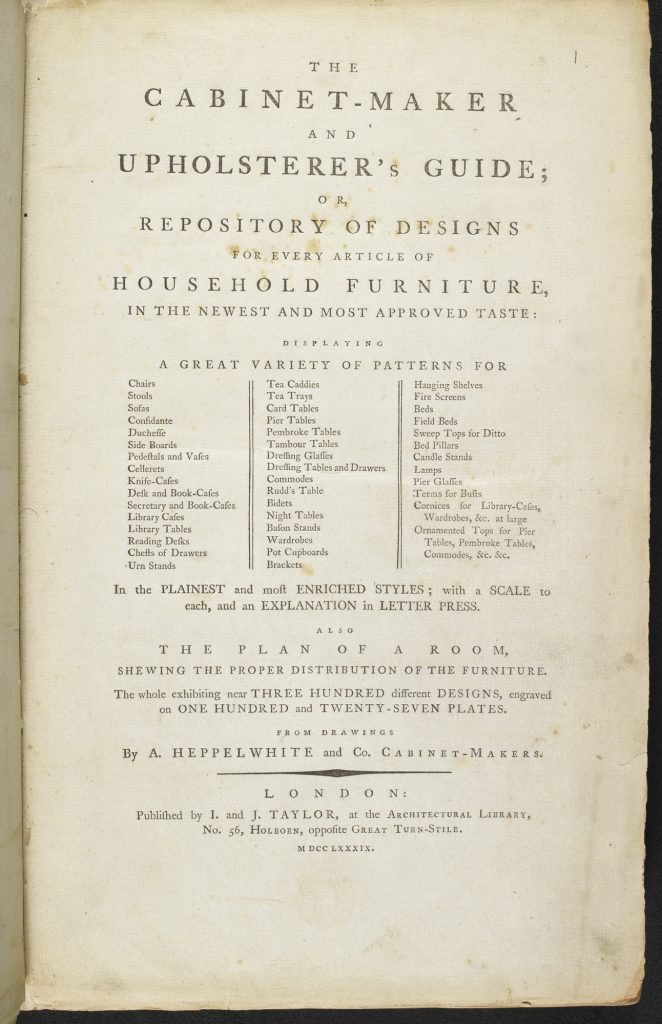

The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1789) demonstrates the variety of finished goods that were manufactured, particularly in London, in response to demands for luxury items.

Most retailers specialised in specific goods and were experts in their particular field: drapers, booksellers, wig makers or hosiers, for example. Most tradesmen issued cards in a local area in order to attract customers and to enhance their reputation. Customers who entered a shop were allowed to handle goods over the shop counter and were encouraged to experience the merchandise on offer: to feel the latest fabrics, for example, or to try on watches or simply relax in new furniture. Like today, the overall experience of shopping was often as important as the quality of the goods themselves.

Shopping for books at Messrs. Lackington, Allen & Co.’s Temple of the Muses, 1809, illustrates the increase in bookselling during the 18th century. This shop is believed to have sold around 100,000 copies each year during the 1790s.

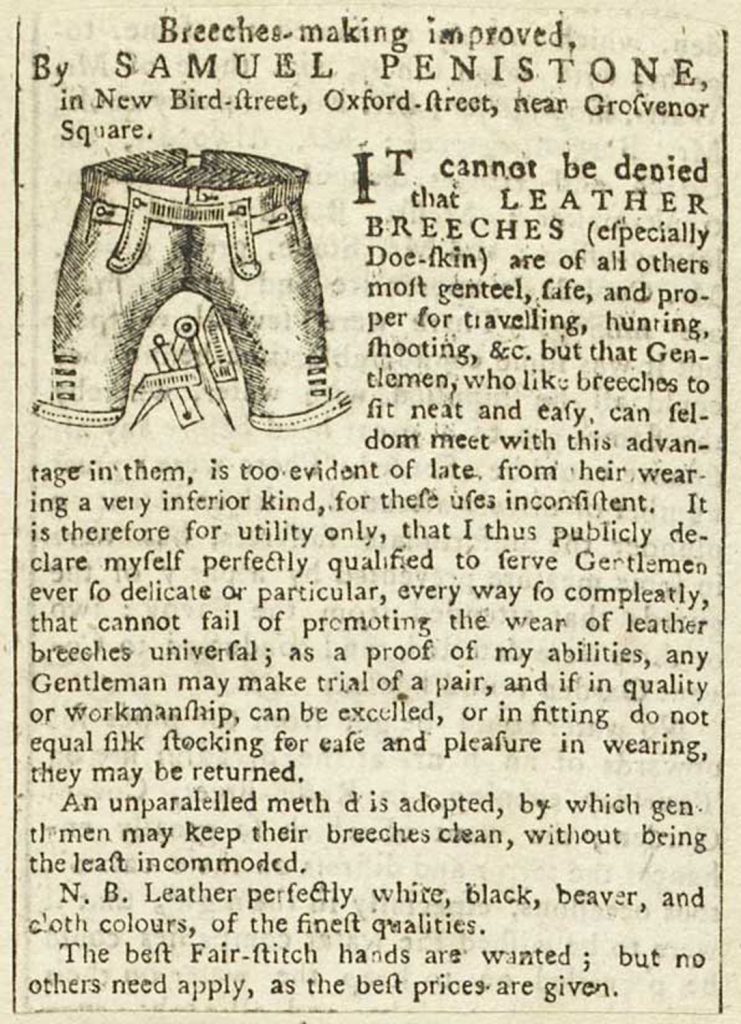

This advertisement for Samuel Penistone’s leather breeches (1775) is clearly aimed at customers of status and wealth.

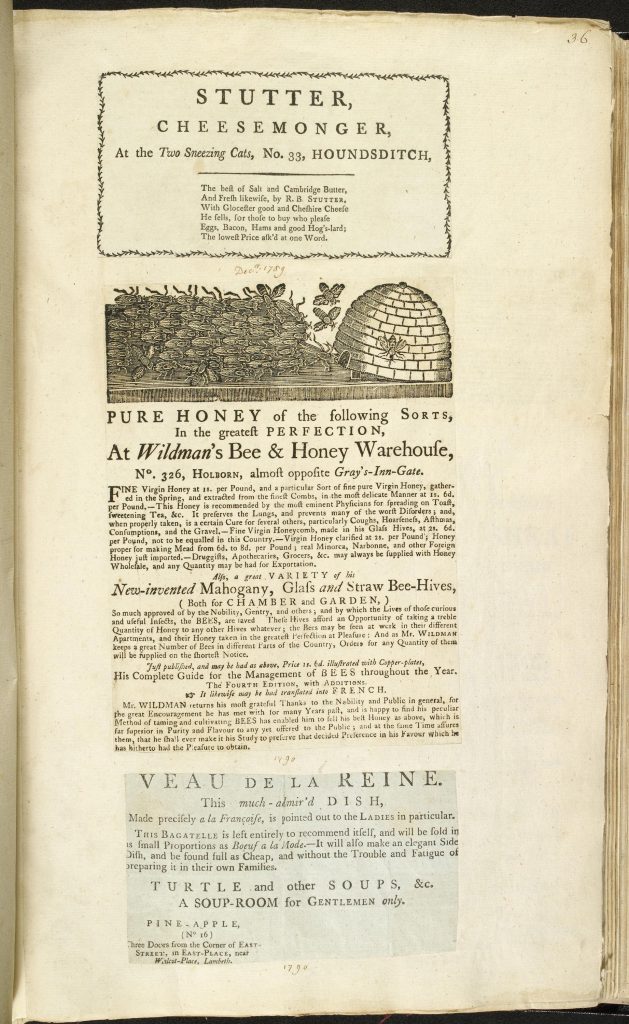

Typical advertisement for consumer goods including cheese and honey as the 18th century saw a growth in material goods.

Clothes

Clothing and fashion were highly important to the wealthy. A single item of clothing often represented the most expensive item in a person’s possessions and new items of apparel were usually highly treasured.

Woollen garments that were heavy and difficult to clean began to disappear gradually after the first half of the century. These were replaced by cheaper printed cotton fabrics that were first imported from India and then later manufactured in the expanding British textile trade in the north of England. Cotton clothes allowed ordinary men and women a greater choice of light and colourful clothing that was durable, easily washed and therefore more hygienic for the wearer.

Increasingly, from the late 1600s, men of all classes wore the familiar three-piece suit: breeches, a waistcoat and long coat. This was all set off with a ruffled shirt, stockings and shoes with buckles. For women, a bodice, petticoat and skirt were usual. Cheaper fabrics were printed with floral or patterned designs, though expensive items were made of silk and either embroidered or quilted. Hats remained in fashion for both sexes: tricorn ‘cocked’ hats were usually worn by men, while women wore caps over which were tied wide-brimmed straw bonnets.

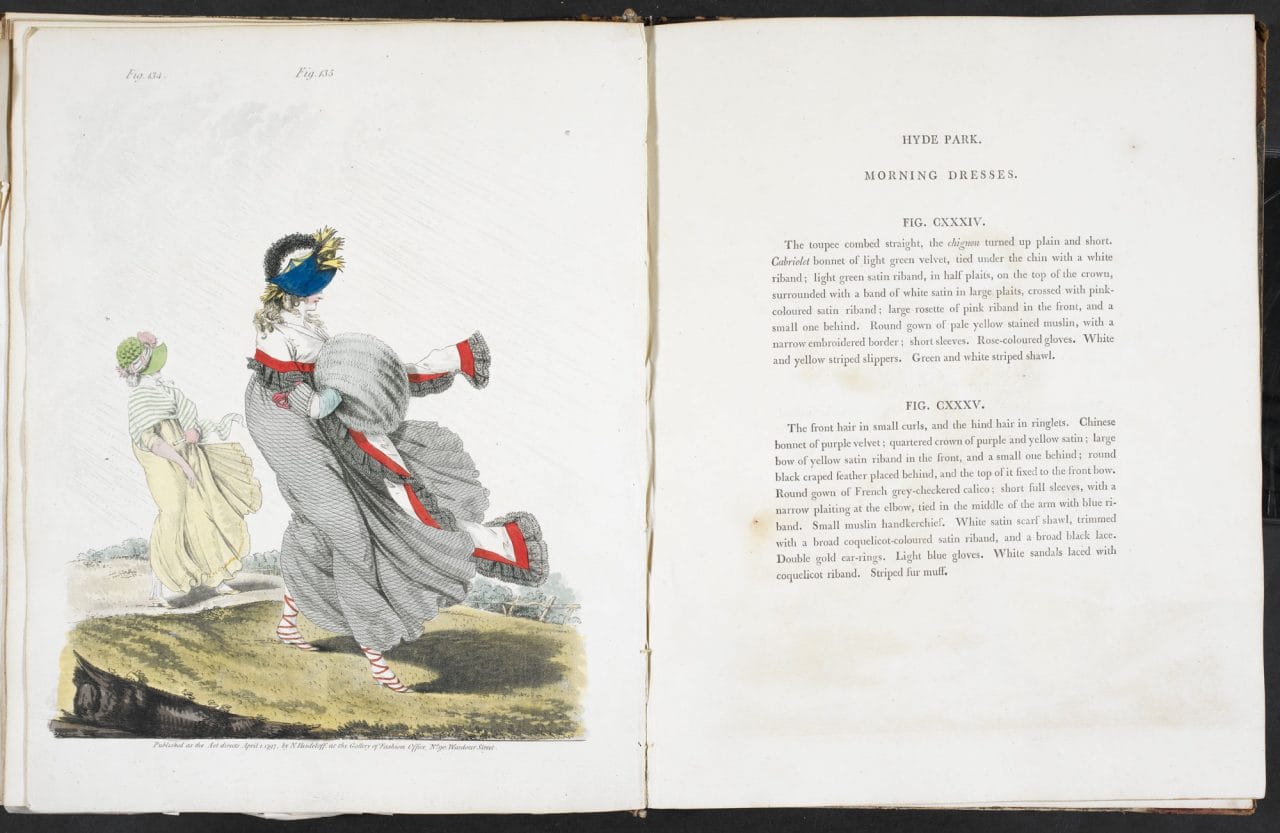

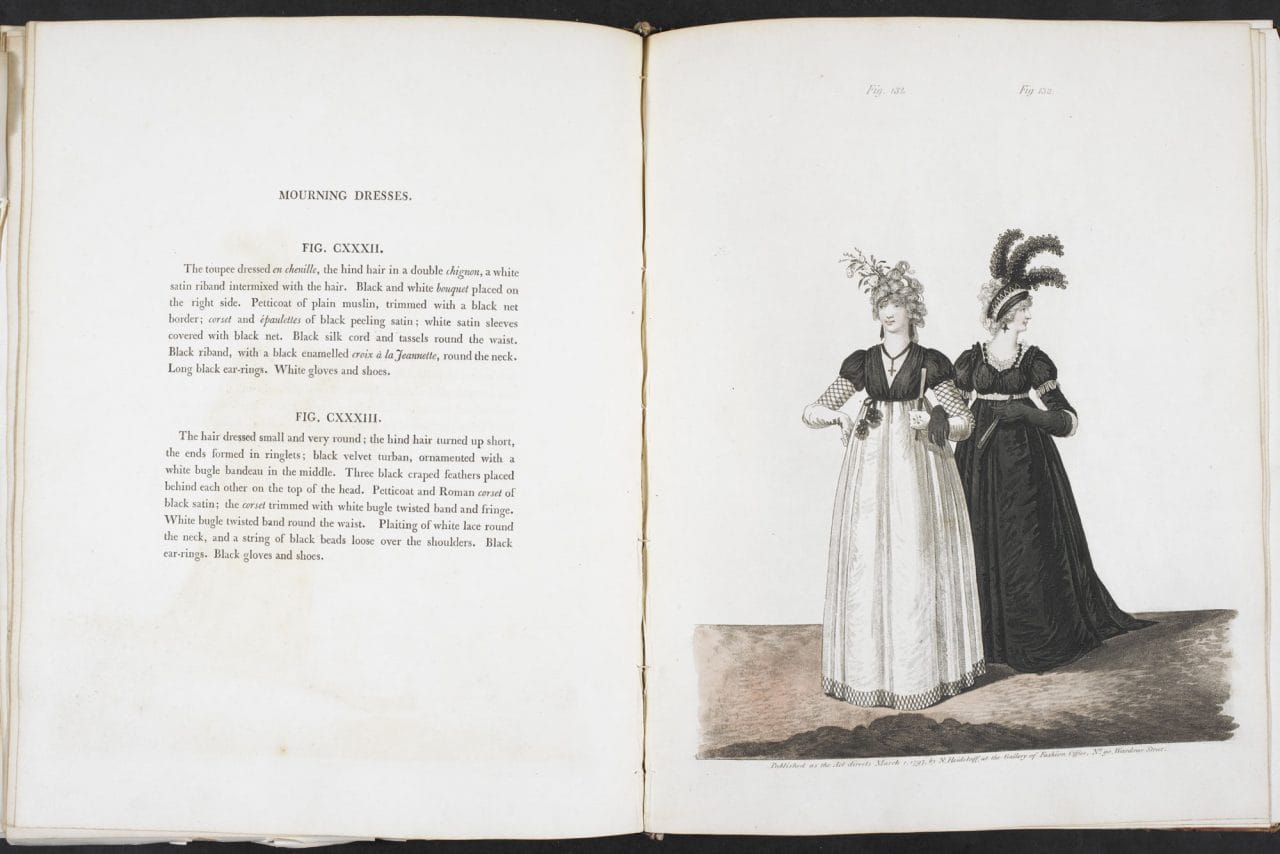

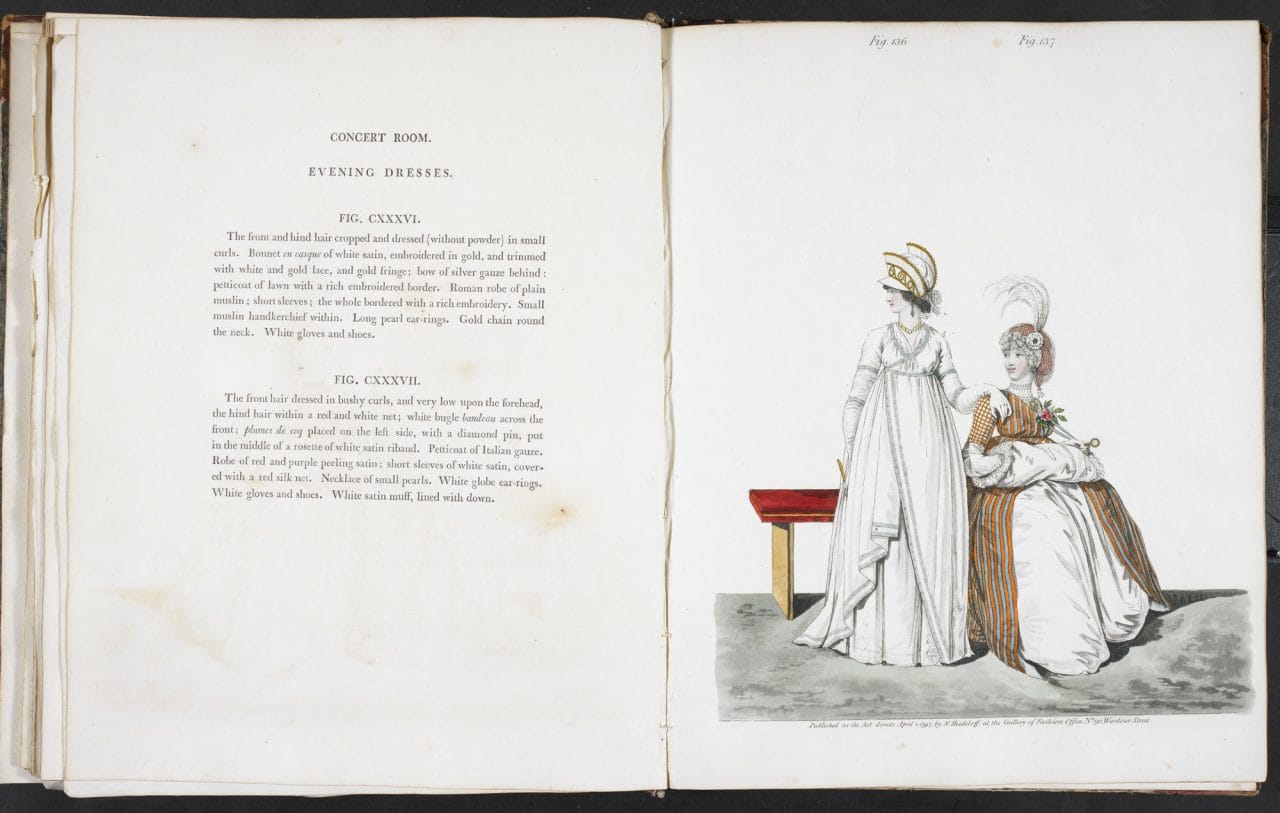

Examples of lavish women’s clothing from the magazine Gallery of Fashion, 1786.

Examples of lavish women’s clothing from the magazine Gallery of Fashion, 1786.

Examples of lavish women’s clothing from the magazine Gallery of Fashion, 1786.

Food

Most towns enjoyed fresh produce as a result of expanding domestic trade. London – as a busy seaport – had regular access to seafood, and tonnes of fresh fish were landed at the city quaysides every day. Fresh fruit and vegetables also arrived from the nearby market gardens and orchards of the Home Counties, and elsewhere other towns held weekly agricultural and livestock markets.

Wining and dining remained fashionable among the wealthy, but for even the poorest members of society eating out was still possible. Most 18th-century towns had a range of cook-shops and taverns where meals could be bought cheaply, and drinks such as coffee and chocolate could be consumed. By mid-century there were perhaps 50,000 inns and taverns in Britain catering to all manner of customers. Coffee-houses in particular became great centres of sociability, where politics were discussed and business transactions conducted. Many banks and insurance houses, such as Lloyd’s of London, owe their origins to this 18th-century ‘coffee-house culture’.

William Hogarth’s work shows the accepted normality of drunkenness in Georgian society with this image from A Rake’s Progress.

Household things

As with food, over the course of this period the objects of everyday life that had once been too expensive for all but the wealthy gradually became accessible to the masses. Mass-produced, cheaper varieties of many household items were now within the grasp of the ordinary working man and woman, who began to enjoy the benefits of a ‘consumer revolution’.

Prosperity and expansion in manufacturing industries such as pottery and metalwares increased consumer choice dramatically. Where once labourers ate from metal platters with wooden implements, ordinary workers now dined on Wedgwood porcelain. Consumers came to demand an array of new household goods and furnishings: metal knives and forks, for example, as well as rugs, carpets, mirrors, cooking ranges, pots, pans, watches, clocks and a dizzying array of furniture. The age of mass consumption had arrived.

The sofa, as an 18th century luxury good, became more popular after 1750 as seen by these Georgian seating designs from The Cabinet-Maker’s Guide.

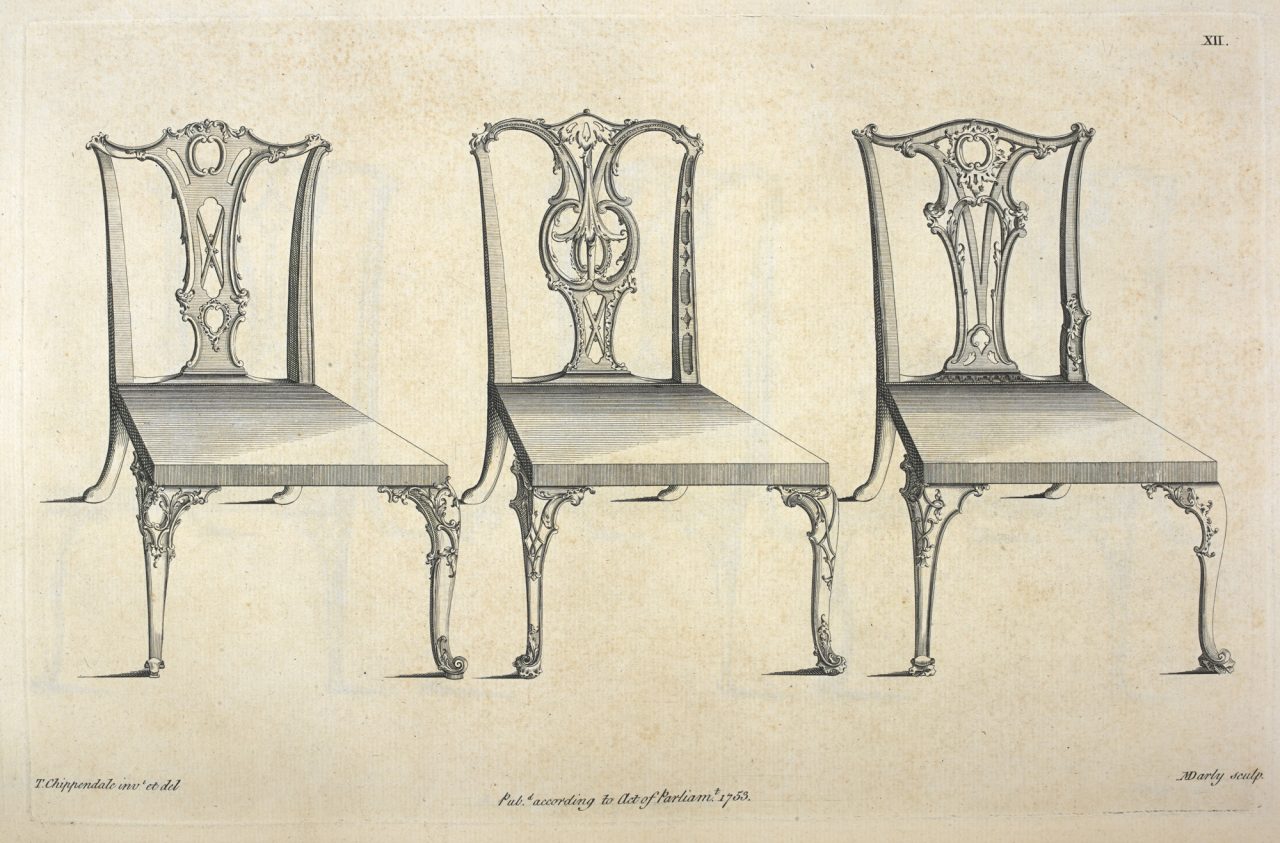

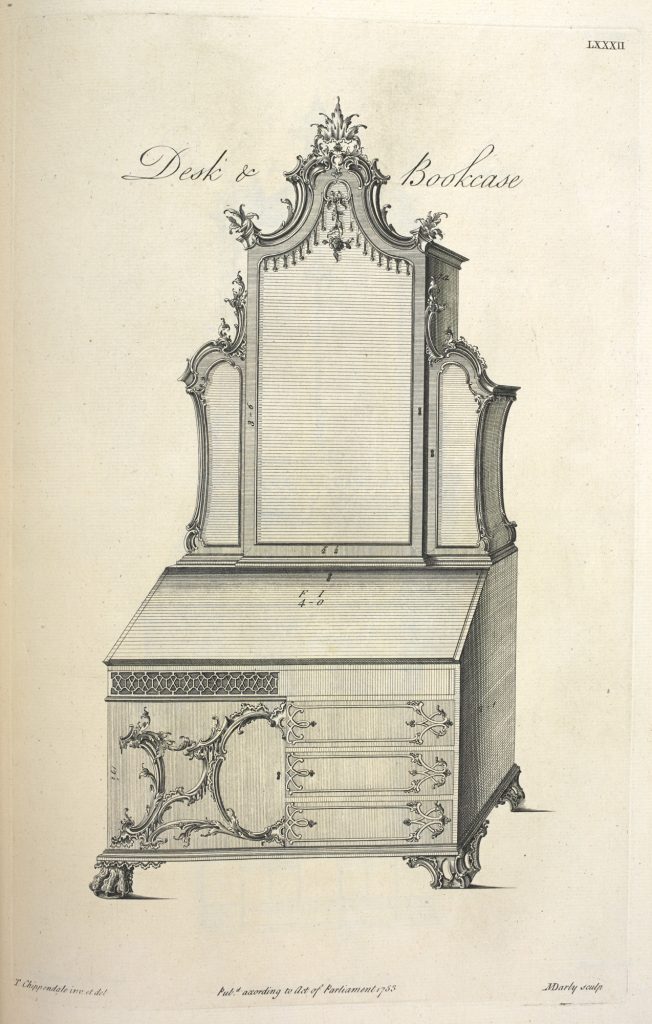

Thomas Chippendale’s designs from The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1854) influenced high-class tastes in furniture for aristocratic and wealthy consumers.

Thomas Chippendale’s designs from The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1854) influenced high-class tastes in furniture for aristocratic and wealthy consumers.

Thomas Chippendale’s designs from The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1854) influenced high-class tastes in furniture for aristocratic and wealthy consumers.

‘Luxury’ and slaves

Greater purchasing power, together with a gradual fall in prices, led to rising demand for new consumer products. Sugar consumption in Britain, for example, doubled between 1690 and 1740, while the price of tea halved. But the wider availability of such luxuries had a darker side. Imports of raw cotton, sugar, rum and tobacco, for example – products that were shipped by the tonne into prosperous British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London – all originated in the expanding plantations of South America and the Caribbean, where merchants depended heavily on African slaves as their primary source of labour.

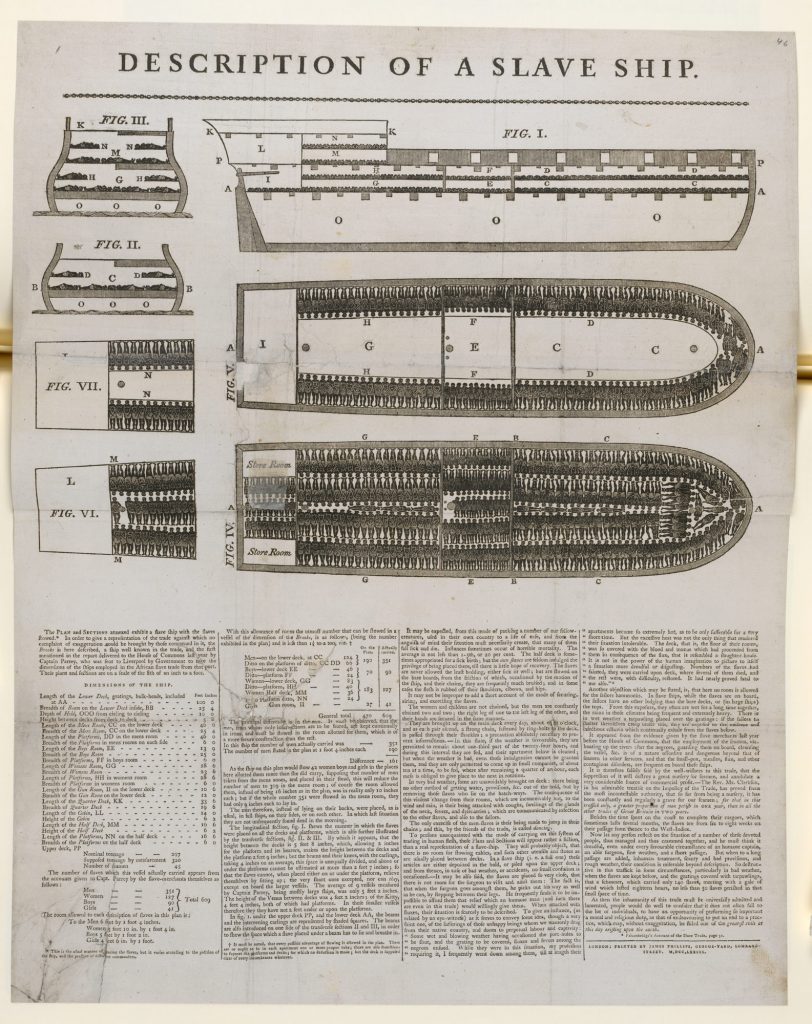

This diagram depicting a slave ship loaded to its full capacity was widely known across the UK. It was an effective piece of propaganda used to raise awareness of the poor conditions on board the slave ships.

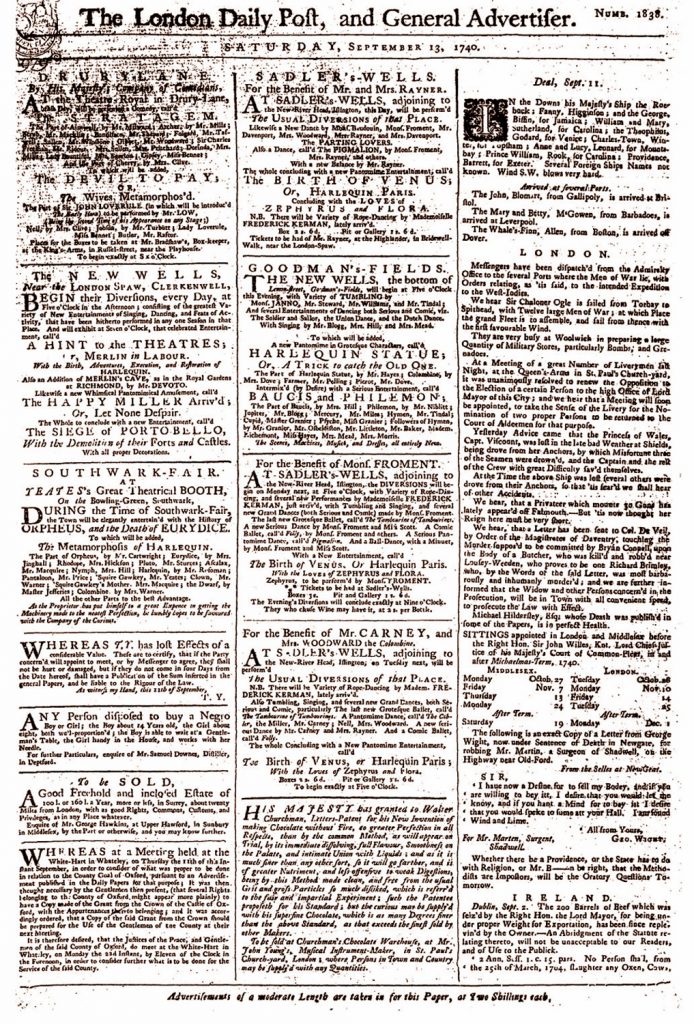

Advertisement for ‘Any persons disposed to buy a Negro’ demonstrates the shocking attitude to slaves which existed in Georgian society. Slavery would not be officially abolished in the British territories until 1833.

Over the course of the 1700s perhaps 11 million slaves were exported by European merchants from Africa to the slave colonies on the opposite side of the Atlantic. As many as one in five slaves died during the journey, after enduring cramped, filthy and dangerous conditions. Thousands of others would die later on the plantations as a result of disease, overwork and maltreatment. Only in the latter part of the century did a forceful British anti-slavery movement emerge, led by evangelical reformers such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson. The expansion of the transatlantic slave trade can thus be located in the growth of British consumer demand, behind which lay the sale into bondage of many millions of Africans.

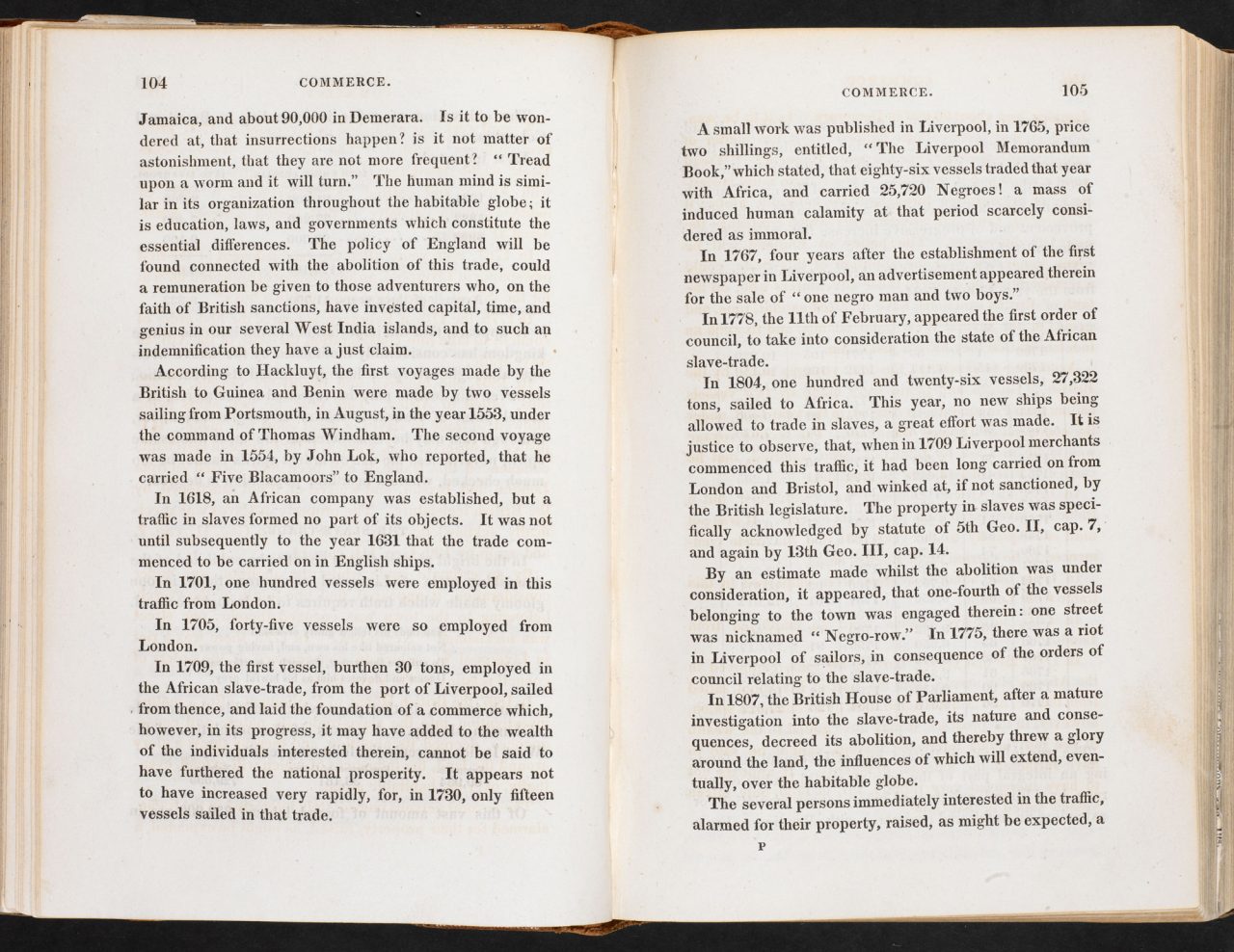

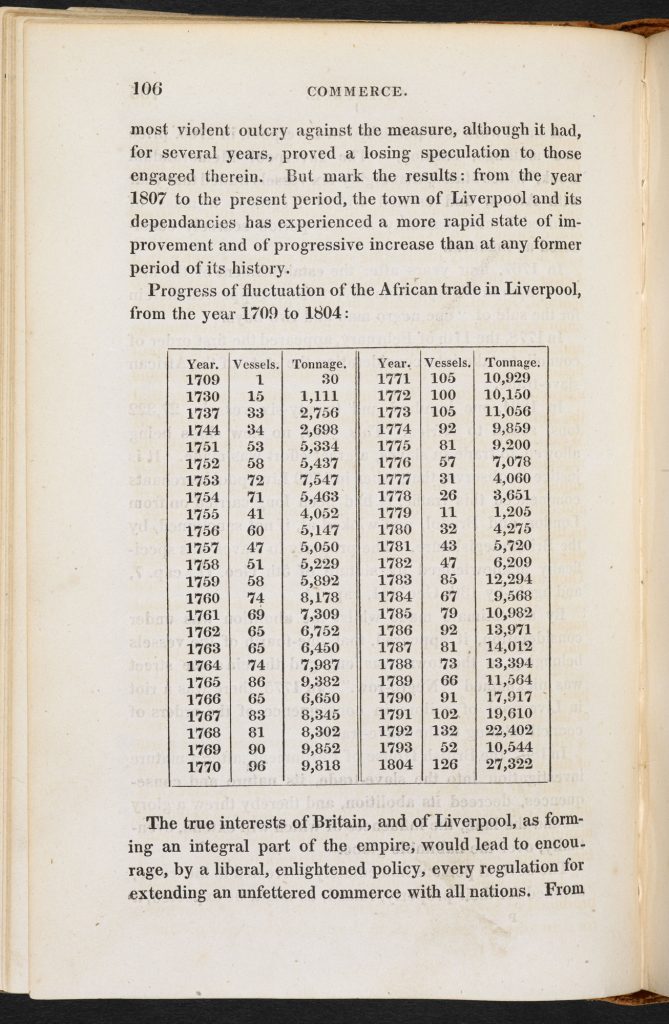

Published in 1825, this account reveals the rapid expansion of the slave trade in 18th-century Britain.

Published in 1825, this account reveals the rapid expansion of the slave trade in 18th-century Britain.

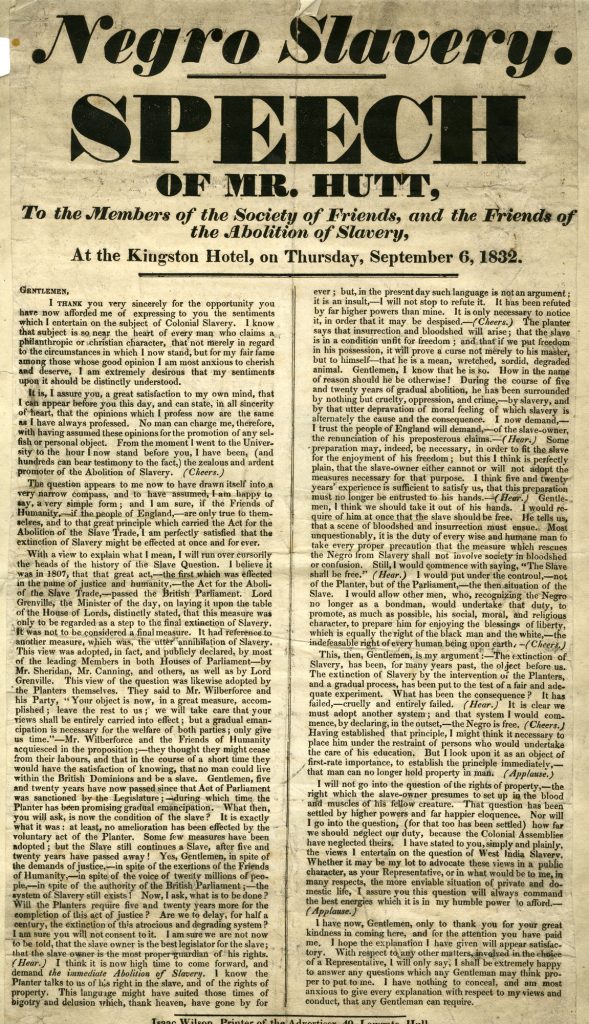

Anti Slavery speech made by an abolitionist political candidate in Hull, 1832. Whilst the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807, the practice of enslavement in British territories was not outlawed until 1833. Speeches like this were used by abolitionists to formally campaign against slavery.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Matthew White

Dr Matthew White is Research Fellow in History at the University of Hertfordshire where he specialises in the social history of London during the 18th and 19th centuries. Matthew’s major research interests include the history of crime, punishment and policing, and the social impact of urbanisation. His most recently published work has looked at changing modes of public justice in the 18th and 19th centuries with particular reference to the part played by crowds at executions and other judicial punishments.

相关文章

The rise of cities in the 18th century

Cities expanded rapidly in 18th century Britain, with people flocking to them for work. Matthew White explores the impact on street life and living conditions in London and the expanding industrial cities of the North.

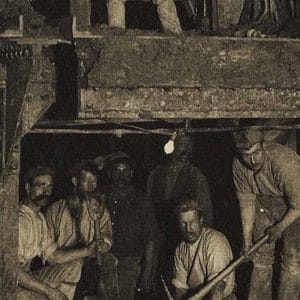

The Industrial Revolution

In this article Matthew White explores the industrial revolution which changed the landscape and infrastructure of Britain forever.

Theatre in the 19th century

At the beginning of the 19th century, there were only two main theatres in London. Emeritus Professor Jacky Bratton traces the development of theatre throughout the century, exploring the proliferation of venues, forms and writers.

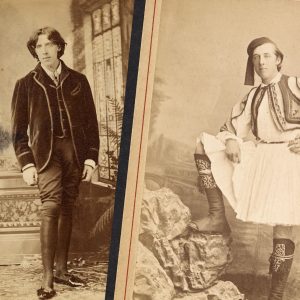

Oscar Wilde and Victorian Fashion

Irish poet and novelist Oscar Wilde was one of the most popular playwrights of the London stage in the early 1890s, and was well known for his bon mots that poked fun at high society. Fashion historian Amber Butchart explores his relationship with fashion.