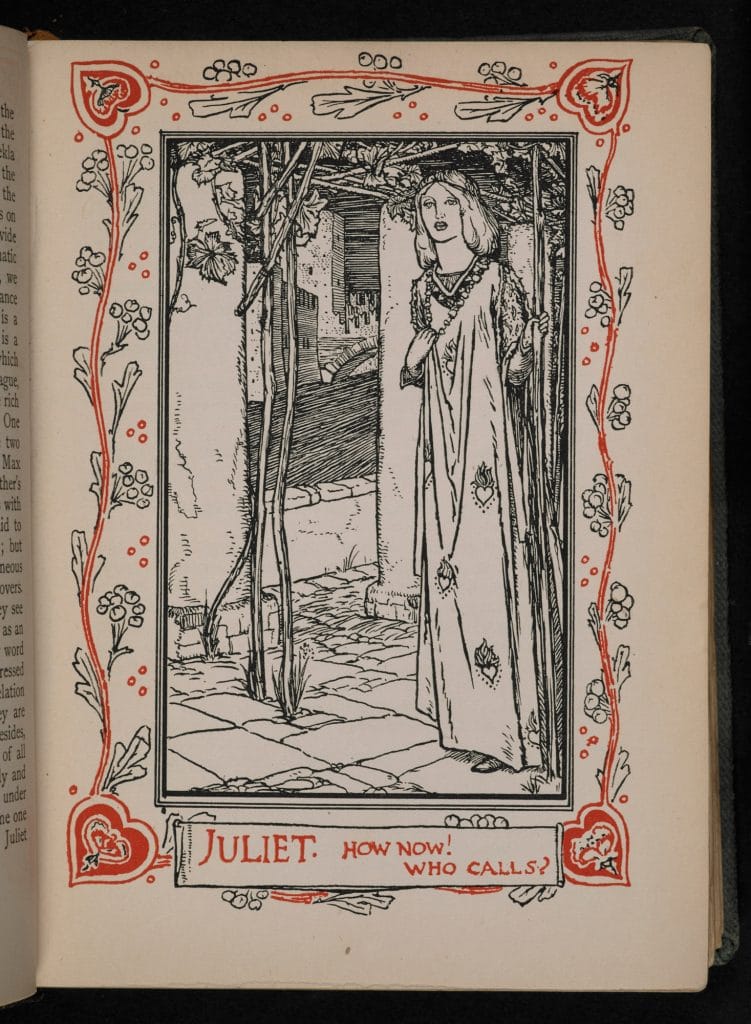

Juliet’s eloquence

Over the course of Romeo and Juliet, Juliet goes from being a sheltered child to a young woman passionately in love. Penny Gay considers how this transformation, and its tragic consequences, are accompanied by Juliet’s development as a poet.

Juliet is the youngest leading female character in a Shakespeare play – she is just about to turn 14. Juliet is also the third-longest female role in Shakespeare; only the much more adult Cleopatra and Rosalind have more lines. A young girl barely into puberty, and yet one who, in the course of the play, takes life-changing decisions and tells the audience about them, in poetry of extraordinary eloquence. What was Shakespeare up to in presenting such a paradoxical figure?

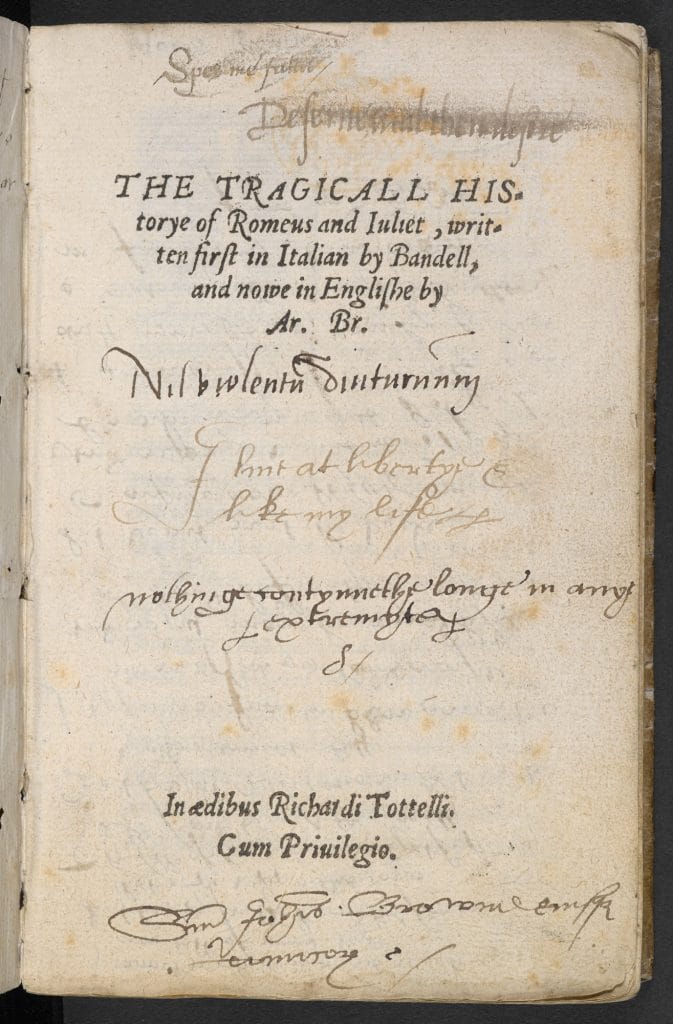

The play’s source material, Arthur Brooke’s narrative poem Romeus and Juliet (1562), was in most respects followed closely by Shakespeare, but not in the matter of Juliet’s age. Brooke’s Juliet is nearly 16; Shakespeare’s is so young that her parents’ attempts to control her life are strong drivers of the play’s narrative. Her father threatens to whip her if she disobeys him (Act 3, Scene 5). She still has as a confidante the Nurse who breast-fed her. Yet her mother, her father and her suitor Paris emphasise that she is ready for an arranged marriage. ‘By my count, / I was your mother much upon these years’, says Lady Capulet (1.3.71–72). Juliet has a mere seven lines in her first scene; it is the Nurse who is talkative, emphasising for the audience exactly how young Juliet is.

Passion lends her power

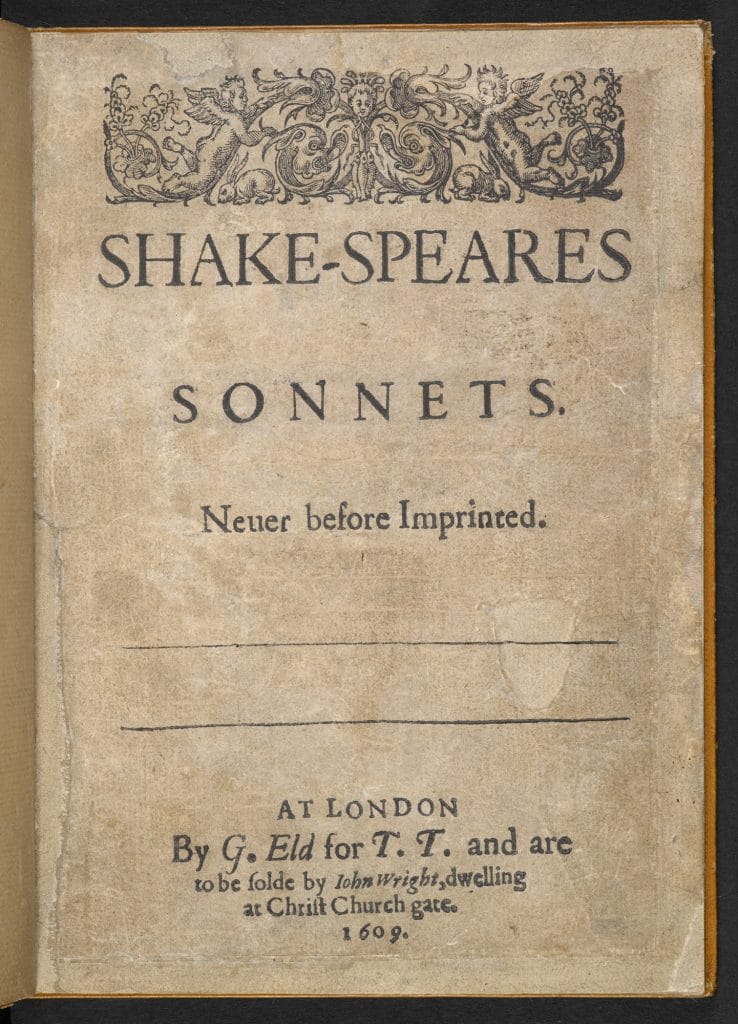

But when she next appears, at the Capulets’ feast, an unexpected side of Juliet is revealed. When Romeo, admiring her beauty, approaches her in courtly mode (‘If I profane with my unworthiest hand …’ (1.5.92)), rather than being coy and quiet, she matches him line for line and wit for wit in a formal sonnet. In this way they jointly – and equally – declare their attraction to each other. Juliet shows herself to be a natural poet, able to play the linguistic games of which the self-consciously poetical Romeo has so far been the sole performer. Yet here is the supposedly uneducated Juliet answering him delightedly in the same idiom:

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this.

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmer’s kiss. (1.5.96–99)

That most famous Shakespearean scene, the balcony scene (Act 2, Scene 1), must have been an extraordinary surprise to the play’s first audience – not only because of its dramatic daring but because Juliet speaks again, and now with even richer eloquence. At first she seems to be talking only to herself – but we ‘overhear’ her (as Romeo does) actually arguing a complex philosophical case:

’Tis but thy name that is my enemy.

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

… What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet. (2.1.80–81, 85–86)

Juliet displays the greater emotional realism in this famous scene of young love. Not for her Romeo’s reaching for poetical clichés, swearing by ‘yonder blessed moon’; rather, she says,

do not swear. Although I joy in thee,

I have no joy in this contract tonight.

It is too rash, too unadvised, too sudden … (2.1.158–60)

Juliet the poet

In the play’s later acts, where the action turns inexorably to tragedy, Juliet is even more expressive. If the plot’s turning point is the violent deaths of Mercutio and Tybalt in Act 3, Scene 1, the play’s more astonishing central moment is Juliet’s 116 lines in Act 3, Scene 2 as she prepares for her wedding night and deals with the dreadful irony that these deaths involve her new husband. ‘Gallop apace’ is a speech of extraordinary imaginative daring: it is full of explicit physical imagery – this young virgin is no naïve innocent – and joyous sexual energy, from the beginning to the end of its astonishing 30 lines.

Is it the adrenalin of the dangerously secret marriage, the experience of sexual fulfilment, or the excitement of discovering her own intellectual and imaginative powers that fuels the rapid development of the child into the woman that we see in the second half of the play? In allowing herself to both think and speak as a poet, Juliet may be seen to be claiming a masculine role. In Act 3, Scene 5 she engages in debate, equivocating with her mother over Tybalt’s death and the proposed hasty marriage with Paris:

I will not marry yet; and when I do, I swear

It shall be Romeo, whom you know I hate –

Rather than Paris. (3.5.121–23)

But her attempt to argue similarly with her father is a step too far; it denies the patriarch’s still absolute social power: ‘How, how, how, how – chopped logic? What is this?’ Old Capulet is affronted that his daughter should have a mind of her own, and his only response to her request to be heard is ‘Speak not, reply not, do not answer me … My fingers itch’, as he threatens to beat her (3.5.149, 164).

Locked into an impossible situation, with parents who refuse to listen to her, Juliet submits to the alternative male authority represented by the Friar: that of the priest and the scientist. Typically, she doesn’t go along with his plan without verbalising at length the pros and cons (mostly cons) as she prepares to take the drug. Her poetic imagination serves her well as she imagines the horrors of waking up in a charnel-house, or perhaps not waking at all because she has been poisoned. But her courage is never in doubt, and at the end of this mighty soliloquy she utters what might be seen as a masculine gesture and turn of phrase: ‘Romeo, Romeo, Romeo! Here’s drink. I drink to thee.’ (4.3.57)

Juliet in the theatre

‘My dismal scene I needs must act alone’, Juliet says as she begins this last act of her story. In employing one of his favourite images – that ‘All the world’s a stage’ – Shakespeare here reminds the audience that they are at a play, in the theatre, where nothing is really as it seems. Perhaps at this point the first audiences were subconsciously reminded of the paradox that this girl who defies her parents – and talks about it – could actually be played only by a teenage boy. (The ‘boy player’ of Juliet might have been any age from 11 to 21, as long as he could keep his voice and gait sufficiently feminine.) And perhaps this is the clue to Shakespeare’s daring in writing this eloquent role: he cannot represent the real 16th-century world on his stage because of strong religious opposition and the misogyny enshrined in English law, but he can present an alternative world, in which young women can express themselves freely and eloquently – though it does not guarantee them a happy ending.

Romeo and Juliet has an assured place now as a potent and familiar myth – not only on the straight stage but also in every type of adaptation – opera, ballet, musical (West Side Story), film – as a popular story of doomed romance. But, looking more closely at Shakespeare’s text, we might argue that the play is more interested in the impossible cultural position of the intelligent young woman, who knows what she wants and speaks of it without fear; argues for her right to it; and in so doing produces poetry that is the equal of that of any of the most passionately romantic heroes in Shakespeare.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Penny Gay

Penny Gay is Professor Emerita in English and Drama at the University of Sydney, and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. She has published extensively on Shakespeare, particularly on the comedies. Her book As She Likes It: Shakespeare’s Unruly Women was published in 1994, and The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare’s Comedies in 2008. She has also written a substantial new Introduction to the New Cambridge Shakespeare Twelfth Night. Her ongoing research interest is in the performance history, both historical and contemporary, of Shakespeare and other English drama, particularly as regards women’s roles.