Shakespeare’s life

From Stratford to London (and back again), from ‘upstart crow’ to ‘wonder of our stage’, Andrew Dickson recounts some of the details of William Shakespeare’s life.

It’s sometimes said that one could cram every known fact about William Shakespeare on to the back of a postcard. That isn’t true – a wealth of historical evidence confirms everything from his family background (comfortably middle-class) to his business interests (extensive). What is true is that little of that evidence gives us access to the man himself, still less the nature of his genius: no manuscripts for major plays, no annotated sources, no intimate correspondence. Only a scattering of anecdotes hint at what he was like; if they agree on anything, it is that Shakespeare kept out of the limelight. In life as in his work, perhaps the greatest dramatist of all time seems to have adopted a motto that creeps into Hamlet: ‘the play’s the thing’ (2.2.604).

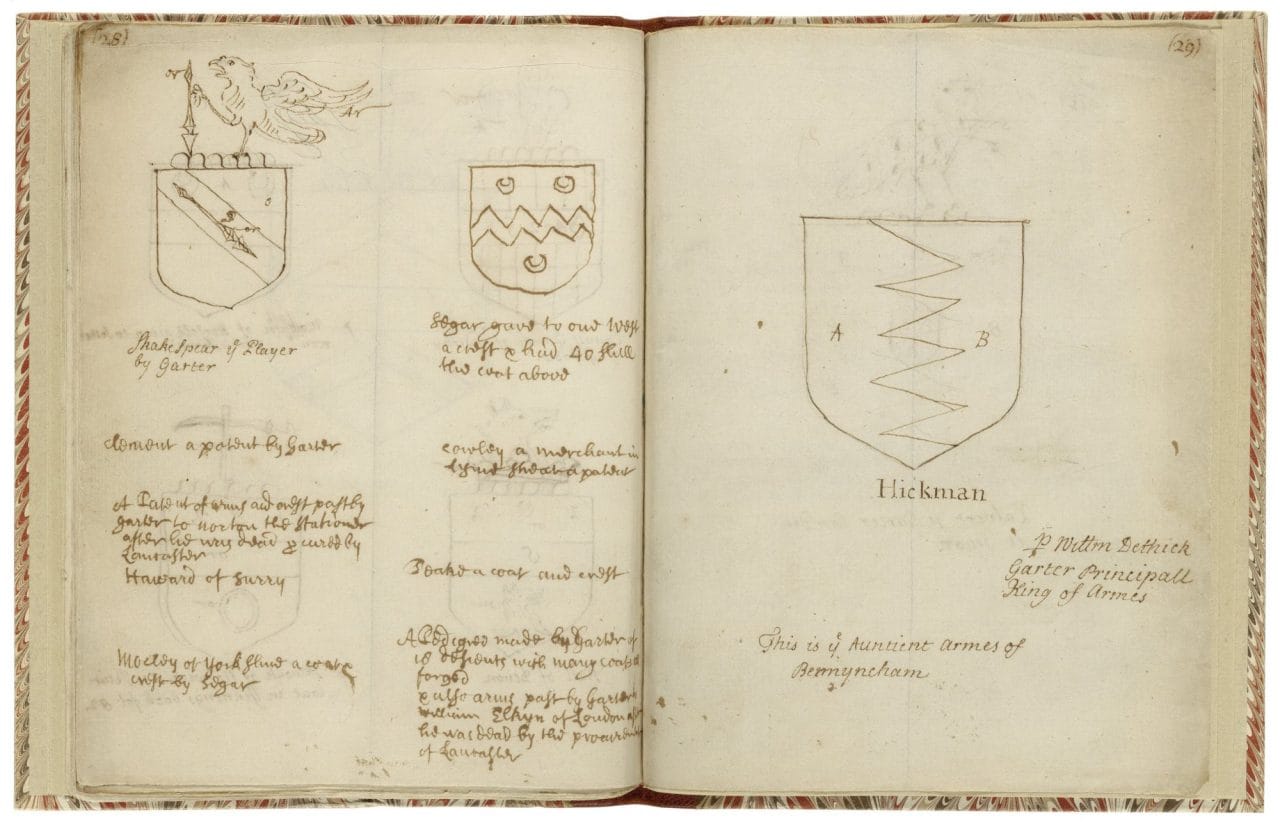

The Shakespeares were prosperous – John was a maker of fine gloves, Mary (née Arden) came from a well-to-do farming family – and when William was five his father was appointed chief alderman, in effect mayor. Though the records have perished, such a position will almost certainly have meant that William was sent to Stratford Grammar School, and his drilling in Latin and Greek language and literature makes itself repeatedly felt in his work. Yet if he had ambitions to go on to university, they were stymied when in late 1582 a local woman, Anne Hathaway, discovered she was pregnant with their child. William was just 18; Anne was 26. The couple had to get married in a hurry, and their first child, Susanna, was christened on 26 May 1583. Twins – Judith and Hamnet – followed in February 1585.

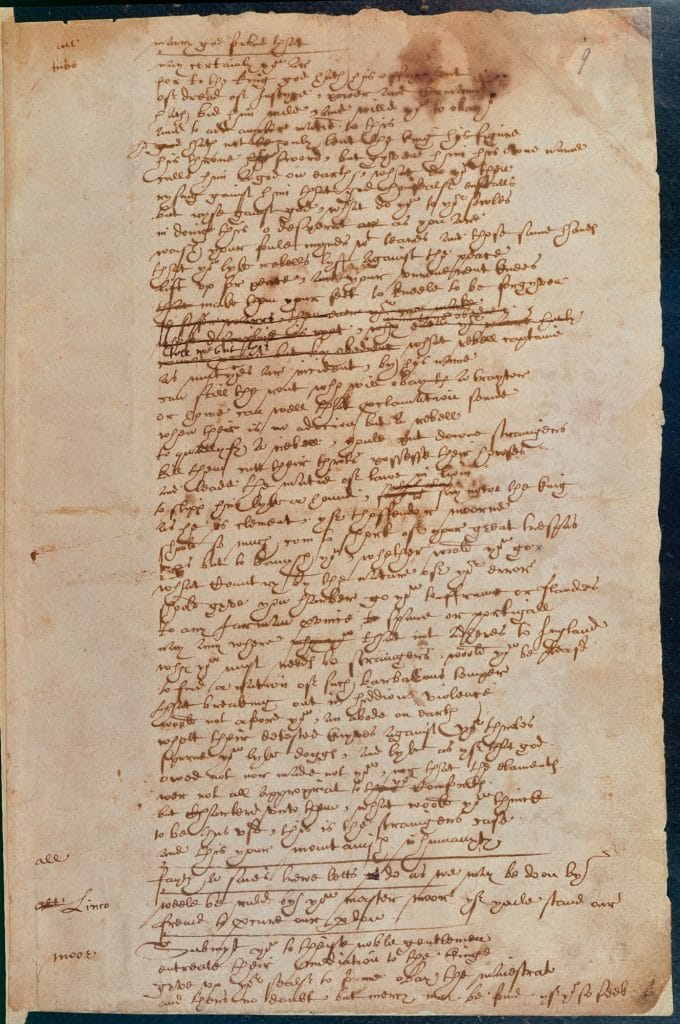

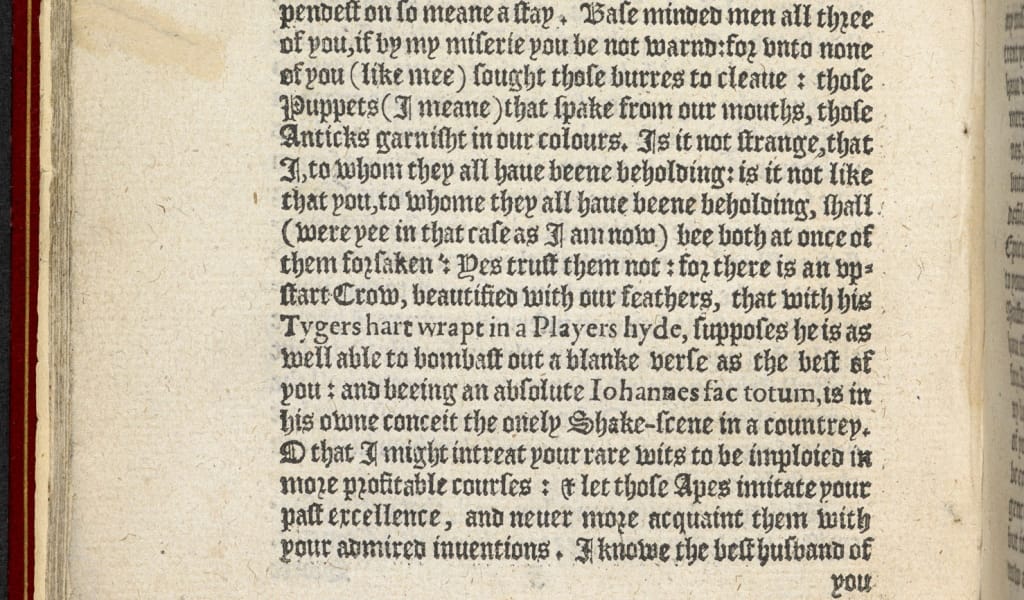

Though it seems possible that Shakespeare remained in Stratford for a time afterwards, no one is sure when he left for London, or how often he returned; the dark seven-year period between the twins’ birth and his first appearance as a playwright is often known as the ‘lost years’. Though his name crops up in a court case in 1589, the next real sighting of him comes in 1592, when a rival writer describes – with tangible bitterness – a talented young ‘upstart Crow … in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene’ making his name with an epic, action-packed series of dramas on the life of Henry VI. Some speculate that the young writer’s first surviving drama is a comedy, The Two Gentlemen of Verona; it’s likely that his gory Roman tragedy, Titus Andronicus, also dates from this period, as do two long poems, Venus and Adonis (1593) and Lucrece (1594). Ambitious and formidably talented, Shakespeare was exploring every creative avenue open to him.

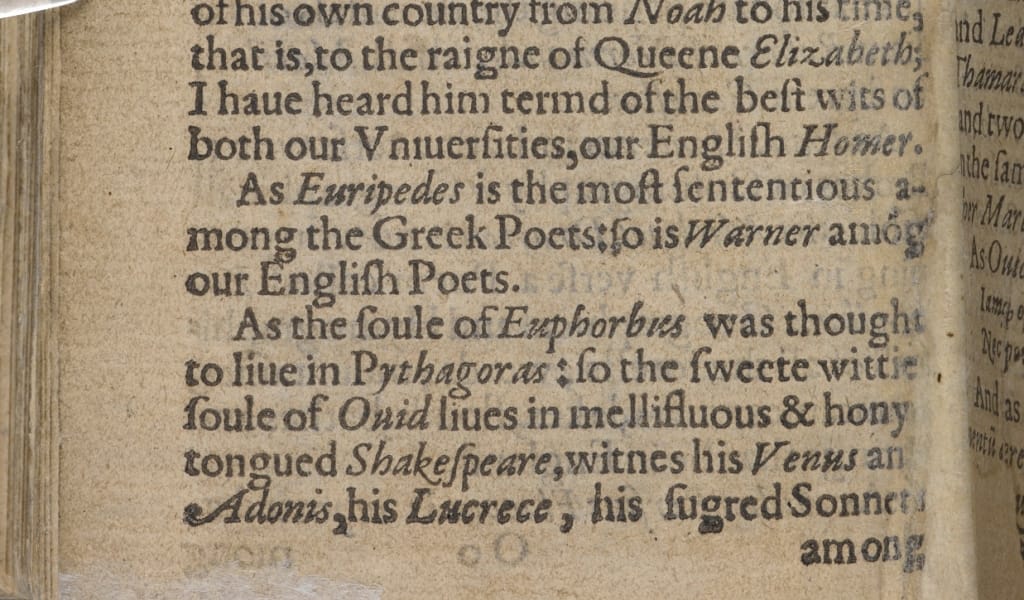

It’s possible that he first got work as a freelance actor-cum-script editor, but in 1594 he became a shareholder in a theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. This unusually stable arrangement lasted for the rest of Shakespeare’s creative life, guaranteeing him a stake in the box office and allowing him to develop close relationships with a tight-knit group of colleagues. Together the company performed at playhouses in Shoreditch and Southwark, most probably scripts including Richard II, Love’s Labour’s Lost and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595–96), as well as earlier titles, including the wildly popular Richard III. They also played before Queen Elizabeth I at court and in legal venues. Shakespeare’s burgeoning reputation is indicated by a panegyric by the critic Francis Meres, published in 1598, which acclaims him as London’s leading playwright and as a ‘mellifluous and honey-tongued poet’ to boot. During this period Shakespeare was busier than ever, turning out scripts including King John and The Merchant of Venice, as well as making a triumphant return to English history in his paired Henry IV plays.

Shakespeare’s offstage life was touched by tragedy in August 1596, when his 11-year-old son Hamnet died of unknown causes. Back in London, more calamity followed soon afterwards when the Chamberlain’s Men ran into problems with the lease on their Shoreditch theatre; over Christmas 1598, they disassembled it and carried as much of the fabric as they could across the Thames to a new site in Southwark. They called the new/old playhouse the Globe; it was most likely that Henry V – the conclusion to the Henry IV cycle – received its debut here in 1599, around the same time as Julius Caesar.

At the Globe, Shakespeare’s writing became more exploratory. An early version of Hamlet, a text he seems to have worked on for a number of years, was possibly on stage by 1600, followed by the agonisingly suspenseful Othello; and his comedies became more double-edged, from the shadowy beauty of Twelfth Night (c. 1601) to the undisguised bleakness of Measure for Measure (1603–04) and All’s Well That Ends Well (1604–05). Some have speculated that the playwright was experiencing some kind of personal crisis – it’s unlikely we’ll ever know – but professionally he had never been so secure.

In 1603, when the Scottish James VI and I took the throne, he quickly took Shakespeare and his company under his wing, rechristening them the King’s Men and guaranteeing them exposure at court. Shakespeare responded in kind, completing his great run of tragedies with two plays – King Lear (c. 1605) and Macbeth (c. 1606) – that responded to the new King’s interests in British history, but with a sharp eye for political realities. Soon afterwards, the King’s Men moved into the indoor Blackfriars playhouse, which seems to have inspired the playwright’s final great phase, a series of mystical, spectacular plays that includes Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. Whether or not Shakespeare was feeling his age – he turned 50 in April 1614 – it might be significant that his final surviving contributions to the stage, Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen (c. 1613–14), were co-written with his much younger colleague John Fletcher.

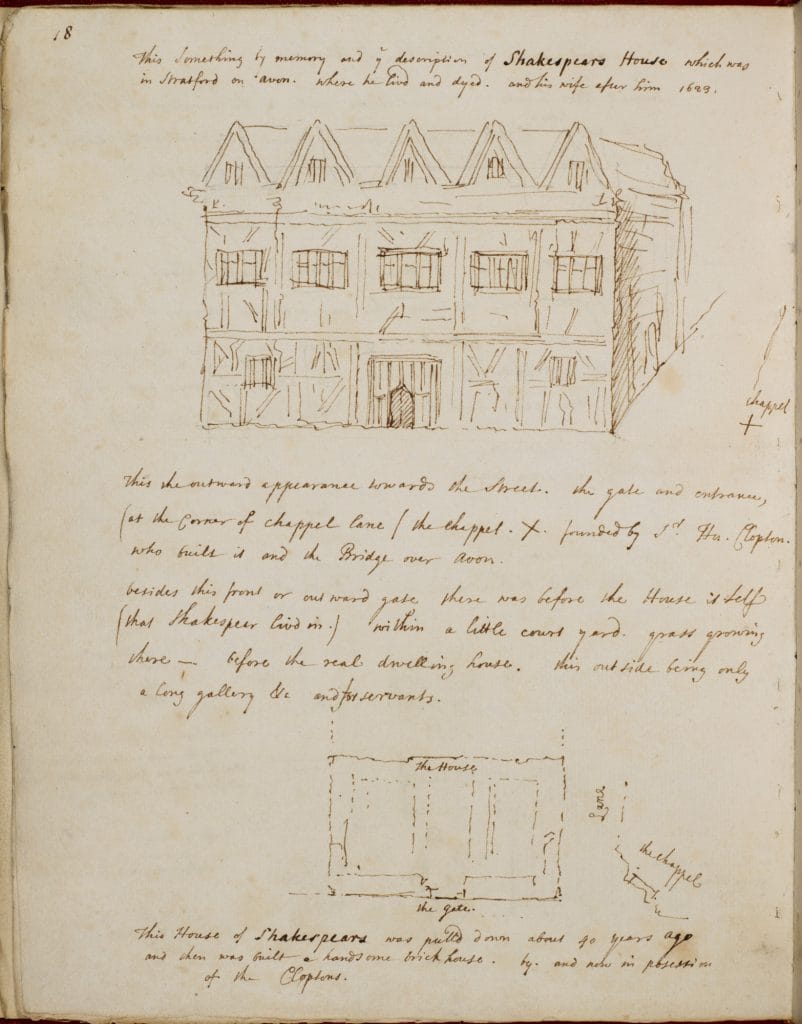

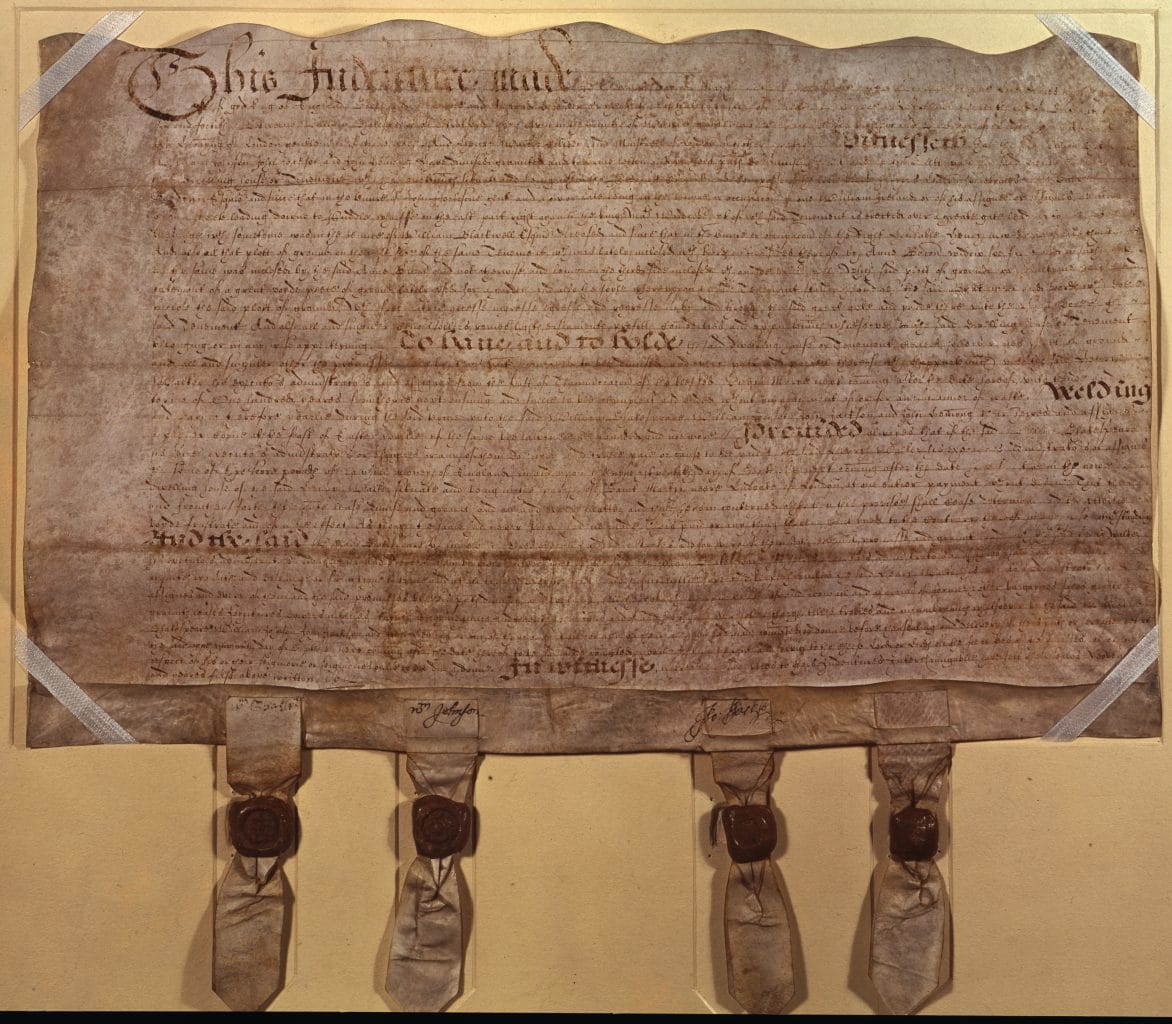

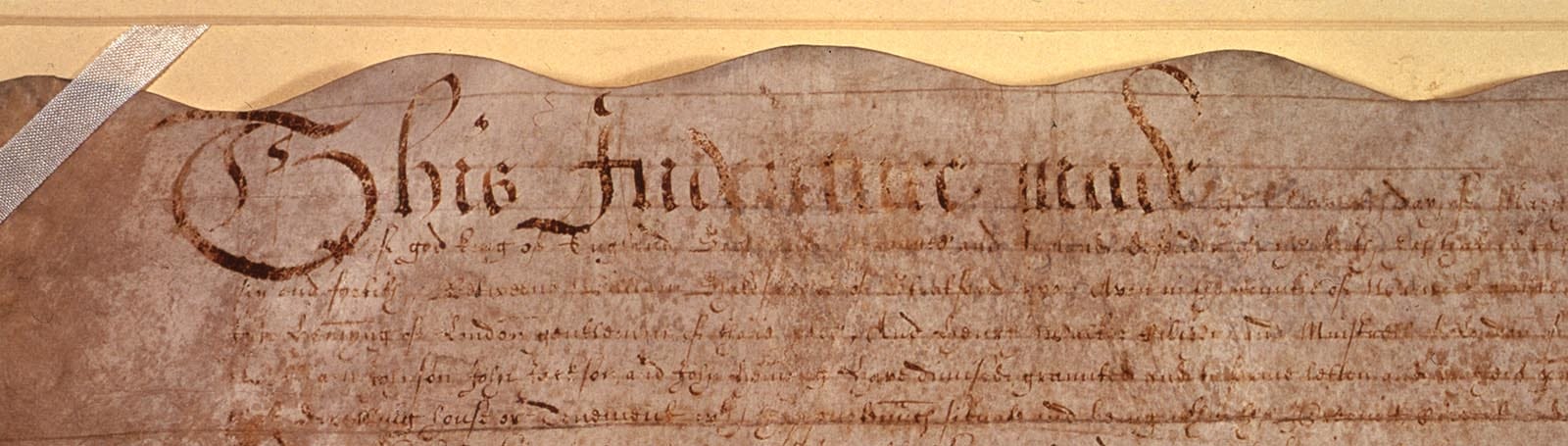

Of Shakespeare’s last years, we know only the bare essentials: that when the Globe burnt down after a prop cannon set fire to the thatch during a performance of Henry VIII in June 1613 he took no part in its rebuilding; and although he bought a pied-à-terre near the Blackfriars a few months earlier, he might have moved back to Stratford soon afterwards. Even if he was in good health when he did so, he did not last long. By March 1616, Shakespeare and his lawyers were drawing up his will. It nearly cut out his daughter Judith (whose marriage he seems to have disapproved of) and, notoriously, gifted his ageing wife Anne his ‘second-best bed’ – two concluding enigmas in a life replete with them. Within the month, Shakespeare was ailing; by late April 1616, he would be dead.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Andrew Dickson

Andrew Dickson is an author, journalist and critic. A former arts editor at the Guardian in London, he writes regularly for the paper and appears as a broadcaster for the BBC and elsewhere. His new book about Shakespeare’s global influence, Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe, was published in 2015. He lives in London, and blogs at Worlds Elsewhere.