‘What a joy it is to dance and sing!’: Angela Carter and Wise Children

Legitimacy and illegitimacy, high and low culture, north versus south London, everything in Wise Children has duality at its heart. Greg Buzwell examines Angela Carter’s last novel, the story of Dora and Nora Chance, the Hazard acting dynasty, and a life lived in the public gaze.

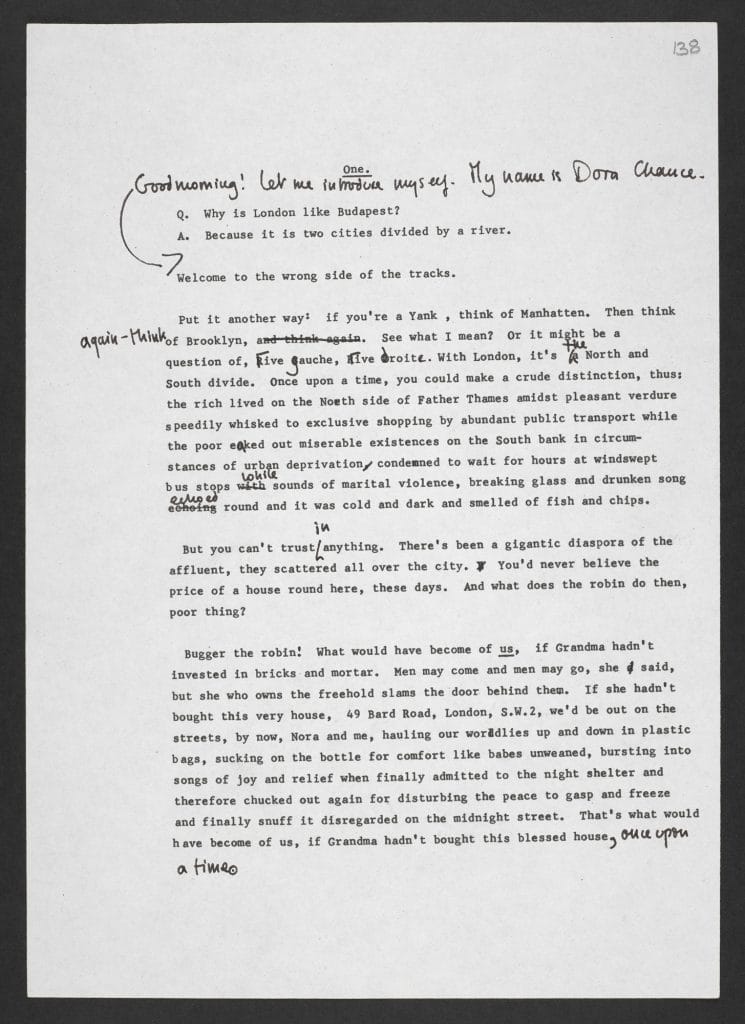

Angela Carter’s final novel, Wise Children (1991), is a riotous and bawdy celebration of life lived on the wrong side of the tracks. Throughout the book opposites are compared and contrasted, with the apparently less-respectable side of the equation often coming out on top. Legitimacy is contrasted with illegitimacy; highbrow culture with lowbrow entertainment, and biological parents with those who take on parental roles haphazardly through either love or circumstance. Everything in Wise Children has duality at its heart. Even the city of London is divided into opposing halves: the respectable part of the city north of the river and its edgier counterpart to the south or, as the narrator of the novel, Dora Chance, describes it, ‘the left-hand side, the side the tourist rarely sees, the bastard side of Old Father Thames’ (Chapter I). Even the narrative styles Carter employed to tell her story take wildly contrasting forms: magical realism, the carnivalesque and fairy tale mingle with realism and a down-to-earth cosy, confessional approach such as the one Dora employs to open the novel: ‘Good morning! Let me introduce myself. My name is Dora Chance. Welcome to the wrong side of the tracks’ (Chapter I). Wise Children is a celebration of life and diversity, a celebration perfectly summarised by Dora’s observation which acts as the keynote of the novel as well as providing its concluding line: ‘What a joy it is to dance and sing!’

Legitimacy and Illegitimacy: “’E’s not your father!”

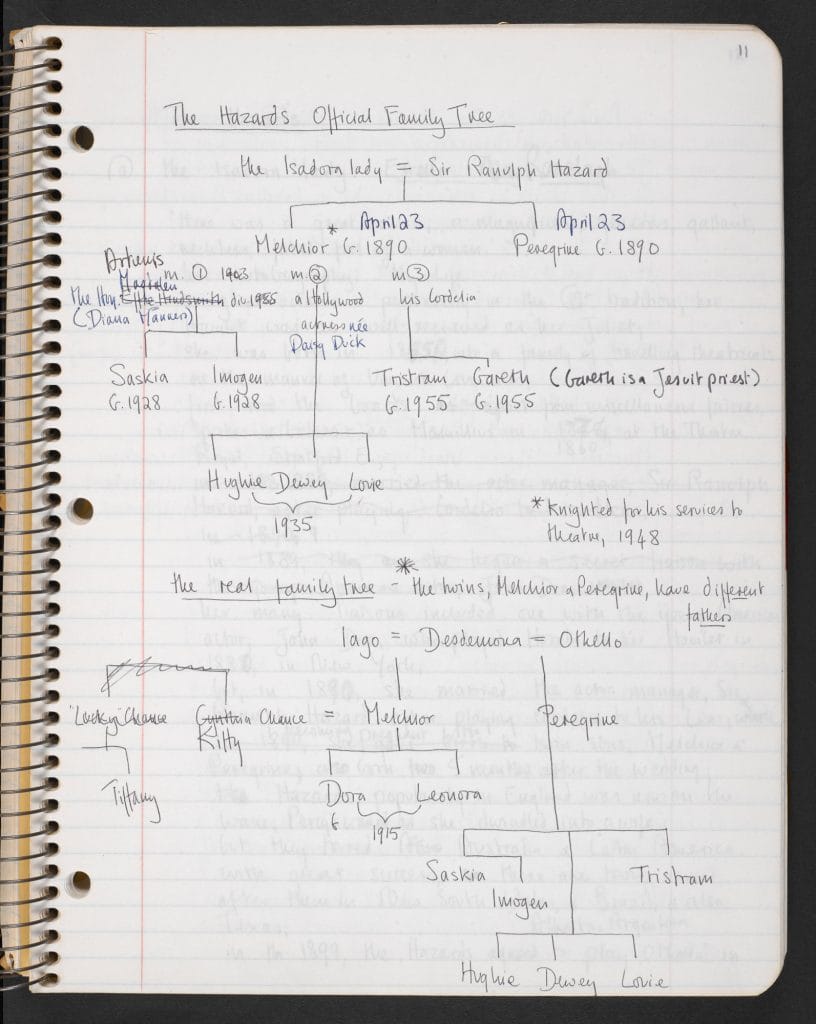

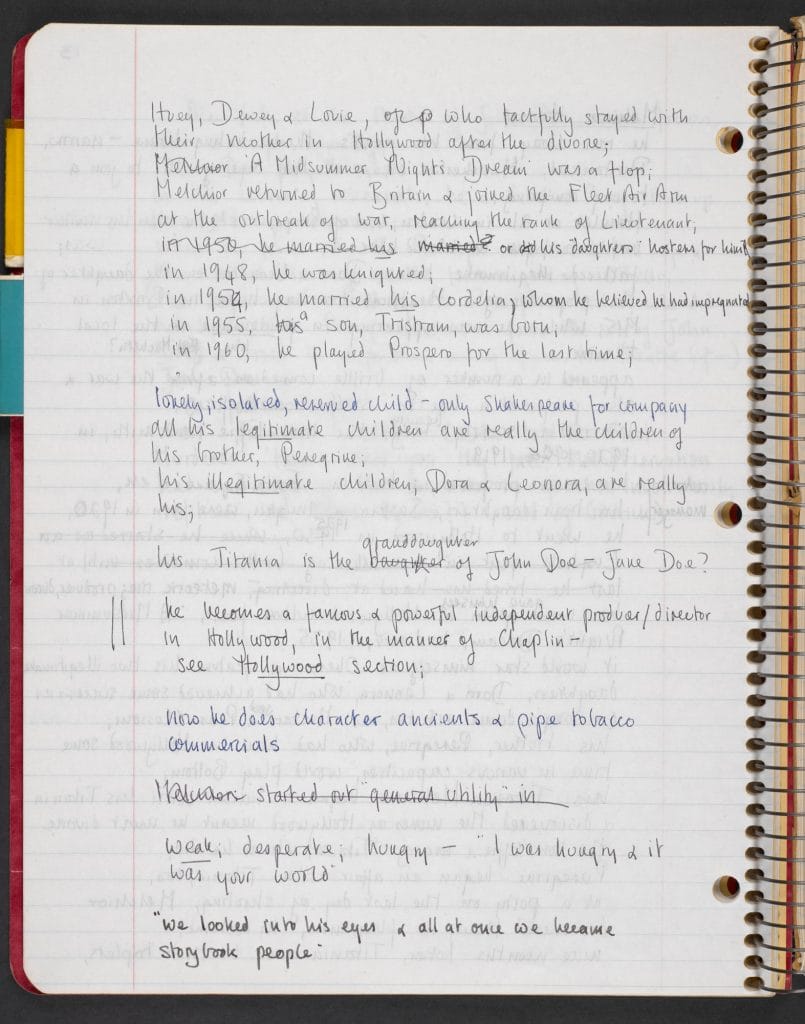

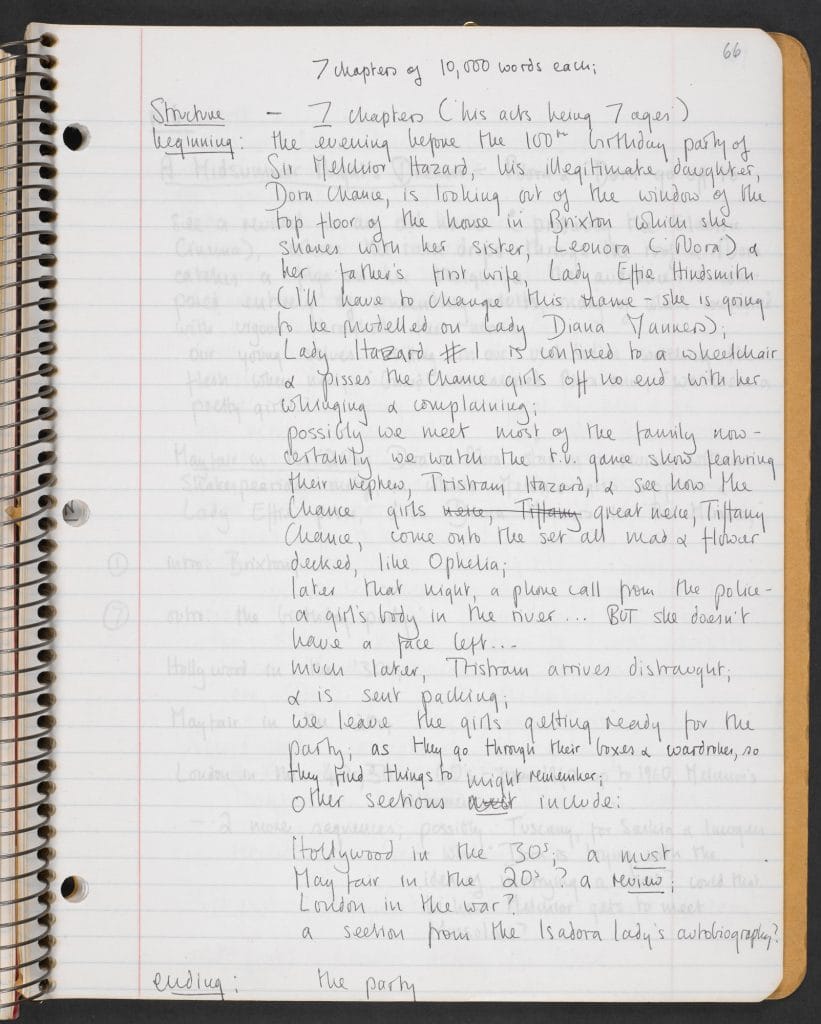

At its heart Wise Children is the story of the Hazard acting dynasty: Melchior and Peregrine Hazard (the twin sons of Estella and Ranulph Hazard) and Melchior’s illegitimate twin daughters Dora and Nora Chance (officially known to the world as the daughters of his brother Peregrine). Dora and Nora’s mother, ‘Pretty Kitty’, dies young and many of the parental duties towards the girls are taken on by Grandma Chance, a mysterious character who almost seems to have invented her own life and history. Her appearance from nowhere on New Year’s Day, 1900, has a dash of the fairy tale about it, signifying as it does a new beginning for the girls. Apart from the brief moments when Peregrine reappears, Grandma Chance runs an entirely feminine household – an early example of how the book overturns cultural stereotypes, in this case that of the all-providing father figure. The lines of parentage throughout Wise Children are nothing if not, as soon becomes apparent, rather opaque. This blurring between the ‘legitimate’ side of the family and the ‘illegitimate’ side is even signposted by the names – ‘Hazard’ being an archaic word for ‘Chance’. Both sides of the family are inextricably linked, but only the Hazard side is regarded as respectable.

The somewhat involved family entanglements, and the gradual unravelling of just who is the father of whom, is brilliantly and comically signposted in an early scene from the book. At the age of 13 Dora and Nora visit Brighton where they see the comedian Gorgeous George performing his stand-up routine on the pier. One of Gorgeous George’s jokes concerns the father of a young man who repeatedly warns his son away from various young women because, so he claims, they all happen to be his illegitimate daughters via his numerous youthful amorous adventures. The young man, disheartened at learning all the women he admires are thus, in effect, his half-sisters, tells his mother of his misfortune only to have her exhort him to ignore the old man’s boasting because, after all, nudge nudge, ‘”E’s not your father” (Chapter 2). Few of the relationships in the book are quite what they initially appear, and as the father/daughter relationships slip between apparent legitimacy and otherwise then so do the social and career opportunities presented to the characters involved. ‘It’s a wise child that knows its own father’, as Peregrine observes, ‘But wiser yet the father who knows his own child’ (Chapter 2).

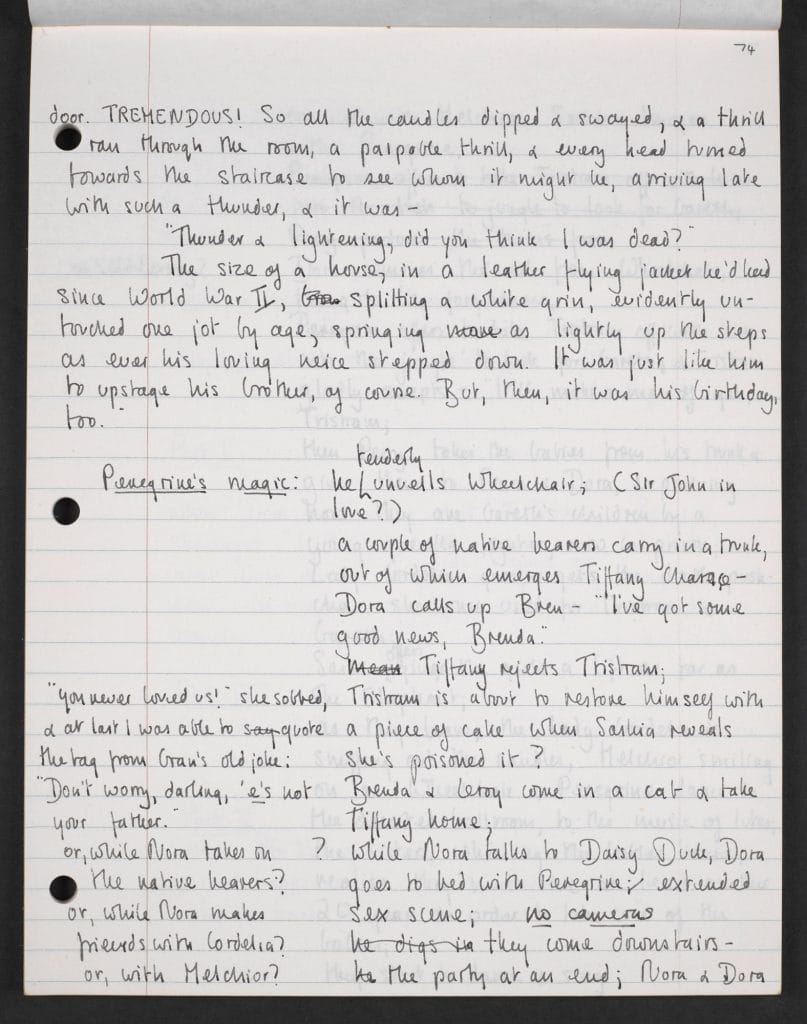

Wise Children takes great delight in exploring the Freudian nightmares inherent in the relationships comprising the Hazard dynasty, and the feelings siblings often have for their parents (and vice versa). Saskia Hazard, the legitimate daughter of Melchior Hazard’s first marriage, twice tries to murder her father and, along with her twin sister Imogen, is implicated in pushing her mother downstairs (or at least of leaving her there once she has fallen). Saskia also has a relationship with her half-brother Tristram. Even when not indulging in such murderous and incestuous activities the Hazard acting dynasty manages to entangle itself in interesting ways upon the stage. On two occasions Hazards playing King Lear end up marrying the actresses playing Cordelia. Even Dora’s name is a nod towards Sigmund Freud – the first case study into hysteria that Freud published in 1905 concerned a young woman, Ida Bauer, whom for the purposes of the publication he renamed ‘Dora’.

Dora and Nora are not only illegitimate by birth; they are also rendered illegitimate by their profession. Not for them the noble Shakespearean productions of their father but rather a life of bawdy turns in vaudeville acts: as Dora observes:

‘Of course, we didn’t know, then, how the Hazards would always upstage us. Tragedy, eternally more class than comedy. How could mere song-and-dance girls aspire so high?’ (Chapter 2).

Dora and Nora perform in touring reviews with titles like Nudes Ahoy! and Goldilocks and the Three Bares. Although never respectable, such a lifestyle allows them to explore avenues denied to their grandiose counterparts. Interestingly, however, this contrast between the professions of the lofty Shakespearean actor and his illegitimate daughters is inverted when television usurps theatre as a provider of mass entertainment and Melchior ends up appearing in the adverts which run during the intervals of TV quiz shows.

‘Brush up your Shakespeare’: Highbrow culture and lowbrow entertainment

Shakespeare is everywhere in Wise Children. The action of the book takes place on a single day, Shakespeare’s birthday, which also happens to be the 75th birthday of Dora and Nora Chance and the 100th birthday of Melchior and Peregrine Hazard; Dora and Nora live at 49 Bard Road; the novel is structured in five chapters, like the five acts of a play, and even the characters owe some of their attributes to Shakespeare – Peregrine for example, his final appearance in the novel dramatically heralded by a mighty wind and swirls of butterflies, clearly owes something to Prospero in The Tempest. Indeed, much of the novel is steeped in the later romance plays such as The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, Pericles and The Tempest, plays in which father / daughter relationships play a key role and rebirth is a defining theme.

Carter uses Shakespeare, and especially his comedies, to explore one of the novel’s many doubled themes – the contrast between highbrow and lowbrow culture. Through history Shakespeare has come to represent the epitome of high culture and literary genius. Actors such as Ranulph and Melchior Hazard derive their authority and lofty public profile from their association with Shakespeare. Indeed the Hazards, via their renown for performing Shakespeare, become the theatrical equivalent of the Royal Family. This, simultaneously, makes them both revered and public property. Just as with the Royal Family the public enjoys the goings on in the Hazard family as they would a television soap opera. High drama and low farce combine in a life lived in the public gaze: ‘The Hazards belonged to everyone. They were a national treasure’ (Chapter 1).

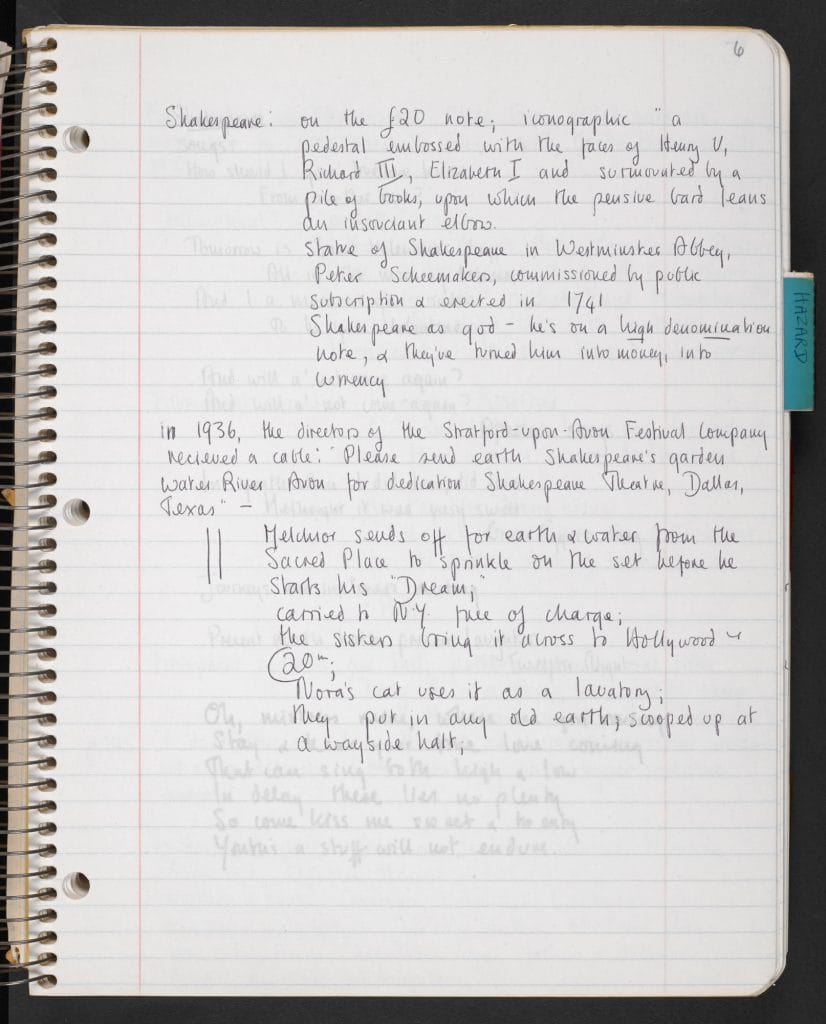

Although Shakespeare represents the epitome of highbrow culture, his plays are often populated by the lowest of the low – bastards, bawds, drunks and murderers. Much of his comedy derives from low farce, sexual innuendo and mistaken identity. At the same time many of the themes explored in his plays such as incest, lust, sexual jealousy and murder are brutally dark. There is a telling contrast between Shakespeare the literary genius, and Shakespeare the popular playwright. Acting in Shakespeare’s day was not a noble activity either but rather something almost disreputable. Indeed, one can argue that acting until relatively recently has been seen as an illegitimate profession, a profession from the wrong side of the tracks. Shakespeare also permeates popular culture and everyday life in ways we don’t immediately realise. The TV shows characters in the book enjoy such as To the Manor Born and The Darling Buds of May take their titles from Shakespeare; his words are used in everyday speech without us realising and his face is even on the £20 that Dora gives to the down-on-his-luck comic, Gorgeous George. Shakespeare not only dominates literature and the theatre, he becomes a figure to represent national spirit and national identity. ‘Shakespeare was a kind of God … It was as good as idolatry’ (Chapter 1).

Shakespeare’s all-pervasive presence allows his work to be appropriated for virtually any form of entertainment because it is instantly recognisable. One of the epigraphs that opens the novel is ‘Brush up Your Shakespeare’ a bawdy song by Cole Porter from the musical Kiss Me Kate which includes lines such as ‘When your baby is pleading for pleasure / let her sample your Measure for Measure’. Carter even manages to add another layer of innuendo on top of this, using the sentence ‘there he was, on the bed, brushing up his Shakespeare’ (Chapter 1). Suggestive and lewd certainly – but one imagines Shakespeare, the literary genius writing to please a popular audience, would have approved.

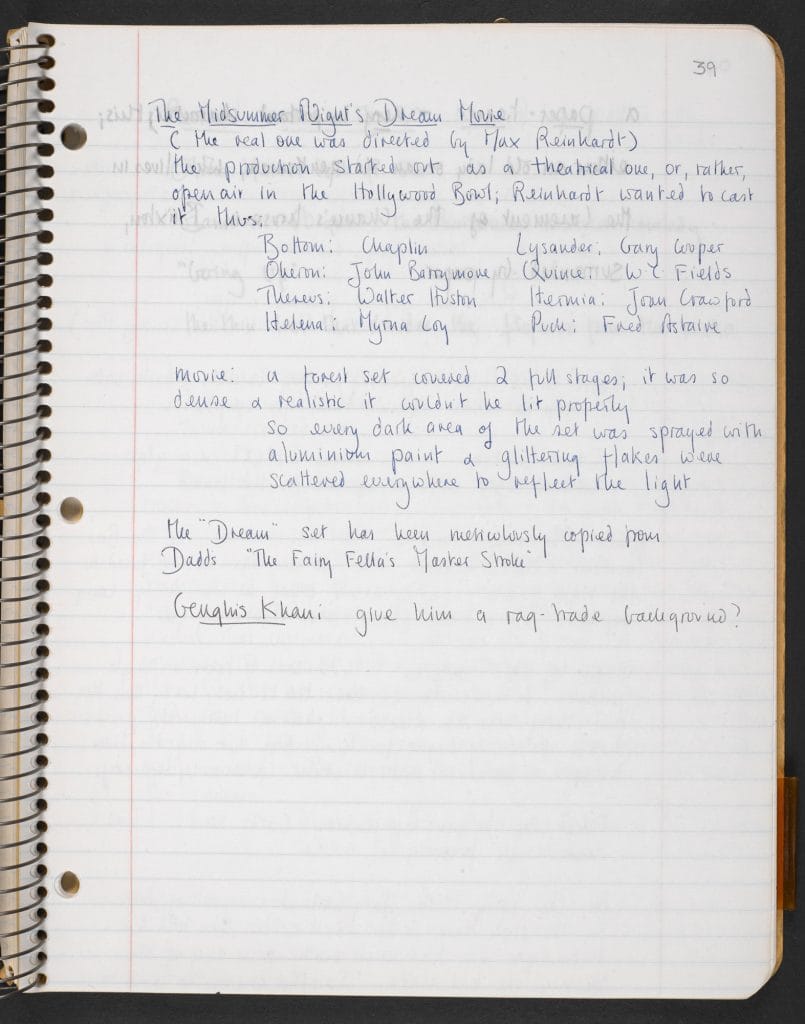

Hollywood

The most jarring clash between highbrow and lowbrow occurs when Dora recounts her experiences in Hollywood making a film adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Hollywood represents the ultimate in popular entertainment and it is no wonder the resulting film is described as ‘a masterpiece of kitsch’ (Chapter 3). Carter based the film in which Dora and Nora appear on Max Reinhardt’s 1935 movie adaptation of the play. The Reinhardt film starred James Cagney as Bottom and Mickey Rooney as Puck, an early example of the relationship between A-List actors and Hollywood adaptations of Shakespeare. In Wise Children the character of Delia Delaney (Daisy Duck), actress and second wife of Melchior Hazard, is based on a mixture of Lana Turner and Jean Harlow, while her ‘peel me a prawn’ line is a nod to Mae West’s ‘Beulah, peel me a grape’ comment from the film I’m No Angel (1933). Irish, Dora’s scriptwriting alcoholic boyfriend, is part F. Scott Fitzgerald, part novelist, screenwriter and satirist Nathanael West and part William Faulkner, all of whom were heavy drinkers in real life.

As part of the symbolic arrival of high Shakespearean culture to the tawdry Babylon of Hollywood, Melchior Hazard, in an echo of Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula, asks Dora and Nora to carry a box of earth from Stratford-upon-Avon to scatter on the Hollywood set of the film. Unfortunately, while travelling by train from the East coast of America to the West, the leading lady’s cat uses the box of earth as a litter tray. Solemn intentions mix with low farce. Dora disposes of the dirt and replaces it with the first bit of fresh earth she can lay her hands on and the ceremony takes place with no one, aside from Dora herself, any the wiser – something that highlights how in Hollywood what you see, and what is actually occurring, are rarely the same thing. Illusion is everything.

Conclusion

Angela Carter’s death in 1992 robbed English literature of one of its greatest talents. Her final book, however, was a parting gift that encourages us to embrace life in all its brilliant, bawdy and quirky variety. If William Shakespeare’s The Tempest is often viewed in the light of the playwright bidding farewell to the stage then perhaps Wise Children, a book so steeped in Shakespeare, can be regarded from a similar perspective. Fittingly for a novel that makes use of fairy-tale motifs nobody in Wise Children dies of old age. All of the deaths are untimely or the result of a tragedy. Given a bit of good fortune there is always a future to be embraced. Wise Children concludes with Dora and Nora Chance unexpectedly finding themselves looking after twin babies, a gift from the centenarian Prospero-like Peregrine. Previously twins in the Hazard and Chance families have been either a pair of boys or a pair of girls. This time around the twins are comprised of one boy and one girl. Dora and Nora, at the age of seventy-five, look forward to playing their new roles – that of joint mothers to the twins. The familiar pattern is about to be repeated, but this time with a refreshing new twist. What a joy it is to dance and sing.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Greg Buzwell

Greg Buzwell is Curator for Printed Literary Sources, 1801–1914 at the British Library; he is also co-curator of a major exhibition on Gothic literature, Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, which ran at the Library from October 2014 to 20 January 2015. His research focuses primarily on the Gothic literature of the Victorian fin de siècle. He is also editing a collection of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s ghost stories, The Face in the Glass and Other Gothic Tales, for publication this autumn.