Taste, place and colonialism in the global music industry

What type of music do you hear most on the radio? What genres are the most streamed on Spotify? Ammar Kalia explores the links between colonialism and the global music industry.

Ask anyone the question ‘what music do you listen to?’ and you are likely to be met with a confounding response that is by turns sweepingly general and unerringly specific. As a music critic, my response would be ‘almost anything’, but also, depending on what day or mood you caught me in: ‘jazz, Stevie Wonder,’90s jungle, Detroit techno, Motown, Fela Kuti…’ – the list goes on.

What we listen to is often governed by taste. Taste is a deeply personal pursuit, one informed by nostalgic recollection, the influences of those we surround ourselves with and an intuitive resonance with an internal emotional reaction. Hence the difficulty and particularity of providing a response to the question posed above. What we listen to is also affected by where we find ourselves – it is a personal pursuit inextricably linked to our time and place. It can be unwittingly political.

Take, for instance, the makeup of the artists that consistently top the charts globally, regardless of genre. The best-selling artists of the 20th century across the globe still come from Europe or America and perform in the English language: the Beatles, Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, Elton John. While in streaming, a platform better reflecting the intuitive listening habits of younger generations, in 2020 Spotify ranked its most listened-to artists as the Weeknd, Justin Bieber and Dua Lipa – English-speaking acts from Britain and the US.

The grass-roots power of social media fandom might have encouraged some variance in chart dominance in recent years – most notably in the K-Pop of groups such as BTS and Blackpink and in the streaming popularity of Latin artists such as Bad Bunny and J Balvin – but more generally and historically, there is the sense of a colonial legacy heavily influencing our cultural tastes, an implicit understanding of the continuing hegemony of the European tradition, as seen in the ways that its music is still so widely disseminated and promoted throughout the world over other forms.

Colonialism and jazz

This is not a question of the artists’ talents or relative merits, but one of attitudes and of the available access to their work. In the British Library’s sound archive, we can find anecdotal evidence of these attitudes throughout history. South African drummer Louis Moholo states, for example, in a 1999 interview how his introduction to the jazz music that he would go on to play came from the BBC radio shows beamed from a nearby British military base in Cape Town. His musical tastes were therefore directly impacted by the legacy of colonialism – ‘it is thanks, and no thanks, to the British who occupied my country’, he says, that he was exposed to and drawn to jazz over other South African folk forms. Without the segregationist consequences of British occupation, too, Moholo would never have ended up exiled from his native country and settling in London, ultimately making a name for himself there by playing with his band the Blue Notes.

Louis Moholo-Moholo on hearing jazz on the radio in South Africa

Title: Louis Moholo-Moholo on hearing jazz on the radio in South Africa Creator: Louis Moholo-Moholo, Denys Baptiste Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C122/376 Copyright: Audio © Louis Moholo-Moholo © Denys Baptiste © British Library (C122/376); Image: © Thielker / Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Louis Moholo-Moholo (b. 10 March 1940) is a South African jazz drummer who has preformed in several bands including The Blue Notes and Viva La Black. Moholo-Moholo moved to London during the 1960s where he made an important impact on the development of British jazz.

This recording is an extract of an oral history interview between Denys Baptiste and Louis Moholo-Moholo in December 1999. Moholo-Moholo discusses how he first discovered his passion for rhythm and drumming by running a ruler over the school fence but, he recalls the performers he heard on the radio while living in South Africa:

… thanks, no thanks, to the English who occupied my country… the British BBC was happening so we heard, we had the opportunity to hear everything on the radio. That’s when I could hear your Charlie Parker, your ‘Big Sid’ Catlett, whom I admire, and your Ted Heath, and your Duke Ellington …

African-American actor and playwright Vernel Bagneris recounts in a 1995 clip how his childhood education at the hands of a white nun in New Orleans included an introduction to only Western classical music and art as a means of stifling any other cultural knowledge. ‘Her purpose in teaching Negroes and American Indians was, she said, to calm the savage soul in us’, he recalls. Bagneris continues saying he felt that because ‘We grew up in that way in a time before Civil Rights. We were seen as a separate class of people trying to achieve the goodness the other race had already accomplished’.

Vernel Bagneris reflects on his early musical education

Title: Vernel Bagneris reflects on his early musical education Creator: Vernel Bagneris, Andy Simons [interviewer] Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C122/265 Copyright: Audio: © Vernel Bagneris © Andy Simons © British Library (C122/265). Image: © Chris Graythen / Getty Images

Vernel Bagneris (b. 1949) is an American singer, director, dancer, actor and writer.

In this interview extract recorded in 1995 Bagneris recalls his first memories of hearing jazz while growing up in New Orleans. He reflects on how his early music education was impacted by colonialism; at school, the nuns charged with his education only taught him about western classical music. Bagneris recalls that one of the nuns told the class that this genre of music would ‘calm the savage soul in within [them]’.

Oral History of jazz in Britain collection

This collection of 200 interviews was assembled between 1984 and 2003. It was formed in order to create a complementary body of original source material to examine subjects such as, but not limited to, the influx and impact of musicians from overseas, the involvement of women and jazz in the regions and Britain’s role in the development of free improvisation during the 1960s.

Oral history recordings provide valuable first-hand testimony of the past. The views and opinions expressed in oral history interviews are those of the interviewees, who describe events from their own perspective. As these interviews are historical documents, their language, tone and content reflect attitudes of the time that may be inappropriate today.

What is considered “World Music”?

And what of this other music, this other art, that Bagneris’s nun had tried to eradicate? In Britain and the US, music from the non-European or non-American tradition has been given the title of ‘World Music’ since the late 1980s. Its conception by music executives as a means of marketing the new-found popularity of fusion records such as Paul Simon’s Graceland was quickly met with opposition at the time. Talking Heads frontman David Byrne wrote a scathing op-ed piece in the New York Times in 1999 called ‘I Hate World Music’. Here he argued that listening to music from other cultures allows for it to change our worldview and to translate what was once ‘exotic’ into part of ourselves. ‘World’ music meant the opposite: a distancing between ‘us’ and ‘them’: ‘It’s a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of western pop culture’, Byrne wrote. ‘It ghettoises most of the world’s music. A bold and audacious move, White Man!’

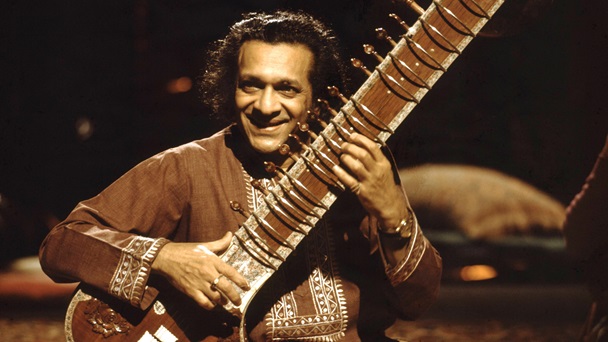

Perhaps one of the best-known proponents of ‘World Music’ was the sitar player and Indian classical composer Ravi Shankar. In an illuminating interview from 1978, he explains to interviewer Mike Sparrow how his music should be treated in the same way as Western classical forms. ‘My music is classical’, he says, ‘there are only two types in the world: Indian classical music and Western classical music’; any others, he argues, are forms of traditional ceremonial music. Instead, he compares his work to that of composers such as Bach, emphasising that it must be ‘respected’, rather than merely having people ‘superficially drawn to it’ owing to its novelty.

Ravi Shankar discusses first reactions to Indian classical music

Title: Ravi Shankar on first responses to Indian classical music Creator: Ravi Shankar, Mike Sparrow Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C1248/360 C1 Copyright: Audio: © The Ravi Shankar Foundation www.ravishankar.org; www.eastmeetswestmusic.com © Mike Sparrow © BBC (C1248/360 C1). Image: © Tony Russell / Redferns / Getty Images

Ravi Shankar (1920–2012) was perhaps one of the best known performers of North Indian classical music.

This interview between Ravi Shankar and Mike Sparrow was likely made in early 1978 shortly before Shankar’s performance on 20 January that year at the Royal Albert Hall, London.

During this interview Shankar discusses his association with other famous musicians such as George Harrison and Yehudi Menuhin and the positive impact of his association with them and the musical genres they were best known for.

Shankar also reflects on how Western audiences react to their first encounters with classical Indian music and vice versa. Shankar talks specifically about the greater emphasis on melody and rhythm in Indian classical music, and how this can be disconcerting for listeners who are accustomed to harmony, modulation and dynamics being more central as is generally the case in Western classical music.

Mike Sparrow Collection

The Mike Sparrow Collection was the first audio collection to be preserved as part of the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project in 2017. Mike Sparrow (1948–2005) was a radio producer and presenter for BBC Radio London (UK) in the 1970s and 1980s, and his collection includes music, reviews, current affairs features and interviews from shows he worked on.

The only barrier to this acceptance is that erected by cultural norms. Shankar goes on to state how the younger audiences he had encountered were more open to his playing because they had fewer ingrained expectations, whereas those ‘regimented in a particular way of listening’ struggled because of its unusual harmonies, rhythms and time-signatures. Ultimately, though, a year after his death in 2012, Shankar was posthumously awarded the Grammy for Best World Music Album – illustrating how his desire to be accepted on his own merits as a specifically Indian classical musician had once again been subsumed by the indiscriminate othering of the ‘world’ category.

Clearly, what we listen to is coded – by our personal experiences and place but also by a colonial legacy which dictates in the wider music industry that anything outside of its Western norm is ungovernable and indefinable. Yet surely that is where the most exciting musical discoveries lie: in the frisson and hyphenated genre tags of cross-cultural collaboration, such as in Kristian Bediiako’s Ghanaian-rock fusion, Spaza’s South African free jazz or Toumani Diabaté’s kora orchestrations. There is indeed an entire world and history of sound to discover – that is the music to listen to.

N.B. Author has edited quotations for clarity.

Banner image © Laura White

撰稿人: Ammar Kalia

Ammar Kalia is the Global Music Critic at the Guardian newspaper. He specialises in writing on the arts and culture, specifically jazz and global music and television. He has published a collection of poetry and an accompanying album, Kintsugi: Jazz Poems for Musicians Alive and Dead, and is currently working on his debut novel.