From Phonautographs to Mp3s: A history of recording formats

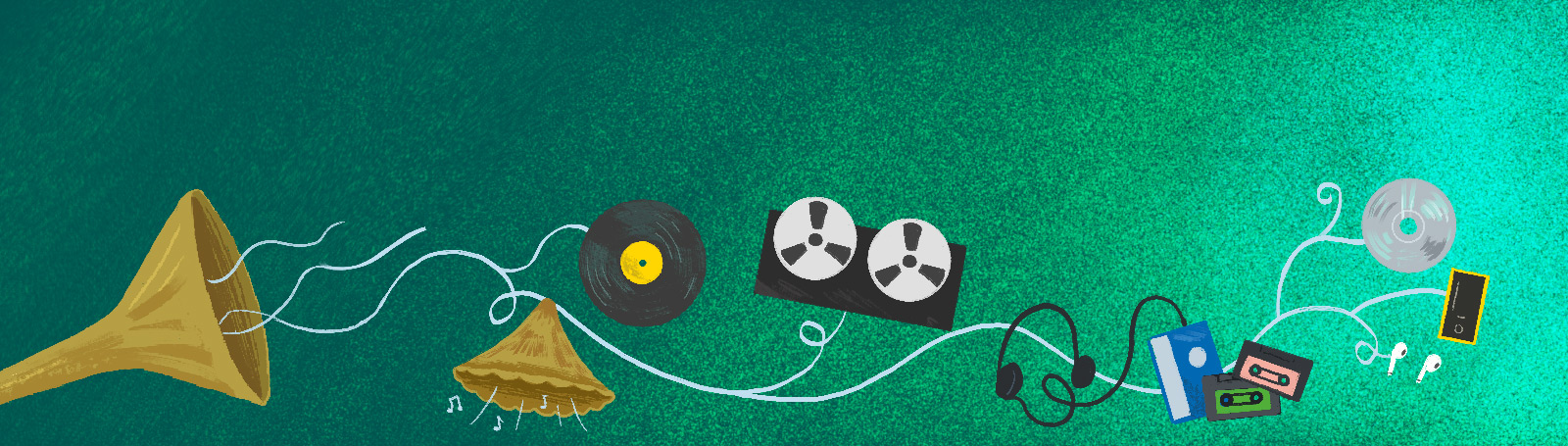

How do you capture a sound, a thing that is unseen and immaterial? Over 150 years ago, long before people began streaming music on their phones without a second thought, a number of bright thinkers set out to unlock the secret to this question. What they discovered was the audio format, a magical object that could contained sound. Like a message in a bottle, with the correct equipment, these formats could capture, transport and play back sounds that would have otherwise been gone in an instant.

This is a short introduction to the history of recording formats.

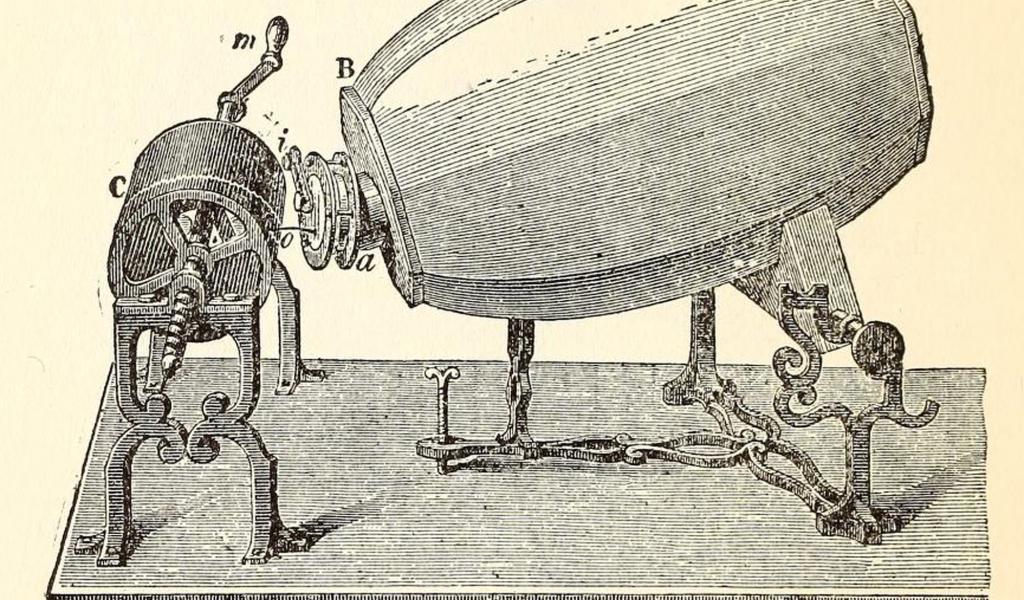

Beginning in 1860, an inventor named Eduard-Leon Scott de Martinville discovered that through his invention, called the Phonautograph, he could capture sound vibrations visually on paper. This early work showed that sound appears in a waveform pattern.

Illustration of Eduard-Leon Scott de Martinville’s Phonautograph

A few decades later, in 1877, the first cylinder appeared on the scene with Thomas Edison’s invention of the Phonograph. These objects contained grooves that stored information about a sound’s tone, pitch and volume. Inventors such as Edison and Alexander Graham Bell were important in the development of cylinders and the machines that used them. Early cylinders were coated with tin, but these soon were replaced by wax cylinders, which were more durable and far superior in sound quality.

Florence Nightingale’s appeal in aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund

Title: Florence Nightingale’s appeal in aid of the Light Brigade Relief Fund Creator: Florence Nightingale Held by: British Library Shelfmark: C1693/1 Copyright: Public Domain

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) served as a nurse in during the Crimean War where her experiences led to pioneering work in improving medical care in the army and the professional training of nurses.

Nightingale made this recording to support the Light Brigade Relief Fund on 30 July 1890 at her home in London. In it, Nightingale delivers a message to the veterans of the Light Brigade, who fought at the Battle of Balaclava in 1854 during the Crimean War.

Originally recorded on wax cylinder, the speech was released commercially as a 78rpm disc in 1935, twenty five years after her death. This transfer has been made from the original cylinder, which was found to hold two different ‘performances’ of the same short speech.

Her famous words read, ‘When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale.’

What was the Light Brigade Relief Fund?

The Light Brigade Relief Fund was set up in response to a public scandal that erupted in May 1890, when it was discovered that many veterans of the charge of the Light Brigade were destitute. The Secretary for War stated in Parliament that he could not offer assistance.

In response, the St. James’s Gazette set up the Light Brigade Relief Fund. Colonel Gouraud, Thomas Edison’s representative in Britain, supported the fundraising efforts by making three sound recordings: this speech by Nightingale, Alfred Lloyd Tennyson reading The Charge of the Light and Martin Lanfried, trumpeter and veteran, sounding the charge as heard at Balaclava.

In 1896, shellac discs were introduced to the world. Discs were similar to cylinders, in that sounds were captured in the grooves of the format, but unlike those on a cylinder, grooves were etched horizontally on the disc’s flat surface. These were popularly known as 78s, as they spun at a rate of 78 rotations per minute. The first discs were only 5 inches in diameter and played about three minutes of audio. As time went on, they increased in both size and playback length. By 1910, flat discs had surpassed cylinders in popularity because they were cheaper to buy and could be mass produced.

Decca portable gramophone, 1919

The Decca portable was introduced in 1914 by the long-established London music instrument maker Barnett-Samuel. This model dates from 1919, and is essentially the same as the popular ‘Trench Decca’ which brought music to soldiers during the first world war.

In 1948, the shellac discs were replaced by slower playing 33rpm discs which could play for longer, on a vinylite material, and the vinyl LP was born.

Moving back a few decades to 1928, the first open reel, or reel-to-reel tapes were developed in Germany. Rather than etching on a hard material, sound waves and forms could be captured on a magnetically coated strip of plastic. This was yet another revolution because through splicing, recordings could be edited and remixed. However, because of the high cost of the equipment, open-reel tapes weren’t very popular with average consumers. Instead, they were mostly used by professionals in radio stations and professional studios.

Nagra tape recorder, 1950s

In 1963, the Dutch electronics company, Philips, released the first compact cassette tapes in Europe. Compact cassettes were a step forward in convenience as they were portable and cheap to buy. Although the quality was lower than reel to reel tapes, they were a hit with the public, who could easily use these formats to record and rerecord, over and over again. In 1979, the Sony Walkman was launched and would become an iconic symbol of the 1980s.

In 1982, the compact discs entered the scene as the result of a collaboration between Philips and Sony. Unlike its predecessors, this recording technology was digital, rather than analogue. The first CDs had a playing time of over 70 minutes, which was rather impressive if you think about the three minute limit for a shellac disc of the same size. CDs sales would go on to surpass those of vinyl in 1988 and cassettes in 1991.

Sony CD player, 1983

Finally, in 1993, the Mp3 was launched by the Fraunhofer Institut in Germany. Although other digital formats, such as the .wav, already existed, the Mp3 became one of the most important commercial digital formats for its ability to compress a large amount of data and maintain reasonably good audio quality. No longer limited to a physical format, it paved the way for our downloading, streaming and listening behaviours today.

In the pursuit for new technologies to be faster, cheaper, better quality than what came before, each new format spurred other inventions and innovations, such as recording and playback equipment, along the way, and have revolutionised how we capture and consume sound.

Banner image © Laura White

撰稿人: British Library Learning

The British Library’s Digital Learning team welcomes over 10 million learners to their website every year. They provide free learning resources that allow audiences to access thousands of digitised treasures from the British Library’s collection, and explore a wealth of subjects from children’s literature and coastal sounds to medieval history and sacred texts.