David Bowie

Drawing on science fiction, Japanese drama and Hollywood culture, among other influences, David Bowie performed a series of identities that challenged sexual and social conventions. Gavin Martin explores how Bowie’s style has inspired musicians from the 1970s to the present day.

David Bowie was the popstar who dared to dream outside the norm. In his teasing and provocative 1970s work, Bowie anticipated a future where gender and sexuality became fluid, rather than fixed, entities.

When David Jones, a wannabe mod(ernist) popstar looking for his big breakthrough, changed his surname to Bowie in autumn 1965 he signalled a determination to go beyond the mundane. The new identity he began to shape would allow him to morph into a 70s Glam Rock god, transsexual alien and cultural shaman constantly seeking rebirth. As the 1970s progressed Bowie’s identity became freakier, anticipating a cyborg future in his emotionally cold Thin White Duke character, ‘throwing darts in lover’s eyes’ and anaesthetised with cocaine.

Drawing on a vast store of influences – kabuki theatre, mime, sci-fi literature, esoteric and occult sources, Hollywood imagery – Bowie excited a new generational pulse. He was Major Tom out in the ether heading further into the future – to new territory, far beyond nominal boundaries of self.

The advent of flamboyant and energising 1950s rock ‘n’ roll icons such as (key Bowie influence) Little Richard had hit like a meteor and caught his teenage imagination. Partly a product of America’s Deep South underground culture of cross-dressing tent shows, Little Richard Penniman epitomised the new music as a transformative realm. Here, both fans and performers could be remade anew – as their polar image opposites or as fantasy figures of their own devising.

As the 60s came to a close, Bowie was primed to advance in a new social climate and, just as the Beatles had set that decade’s musical pace, so would he in the 70s.

The Beatles had lived through and even presided at a social awakening that included liberalisation of laws regarding the voting age, women’s rights and sexual freedoms. Bowie’s career would explore the sort of world and identities that could be created in this dispensation, effecting deep cultural change in the process.

Drawing on the surreal musical hall of Anthony Newley, Bowie had failed to produce a hit with ‘The Laughing Gnome’ in 1965. But four years later the confluence of Stanley Kubrick’s landmark movie 2001: A Space Odyssey and the contemporaneous Apollo 11 trip to the moon chimed perfectly with ‘Space Oddity’. Creating Major Tom, a lone voyager setting off into the great beyond, Bowie earned his first Top 10 UK hit, and sounded a sort of fin de siècle clarion call to fellow travellers for the journey ahead.

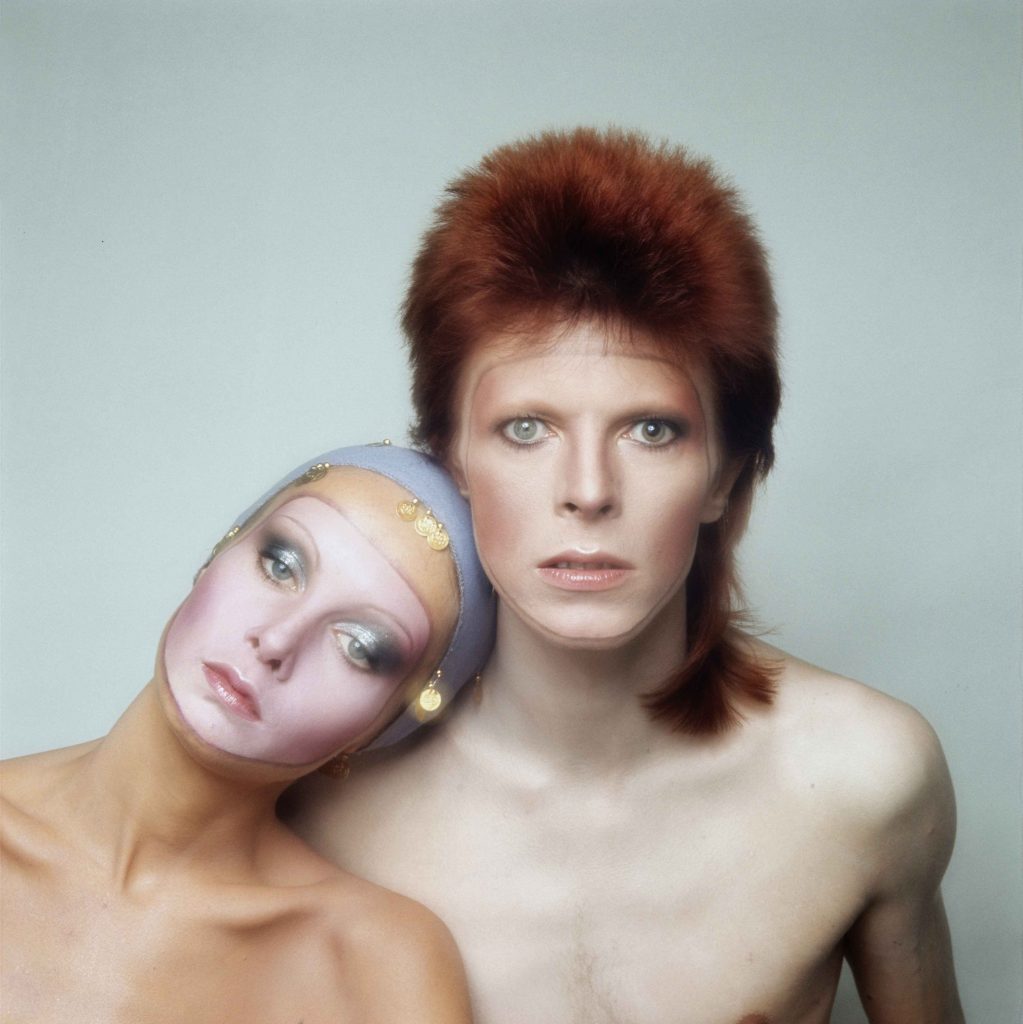

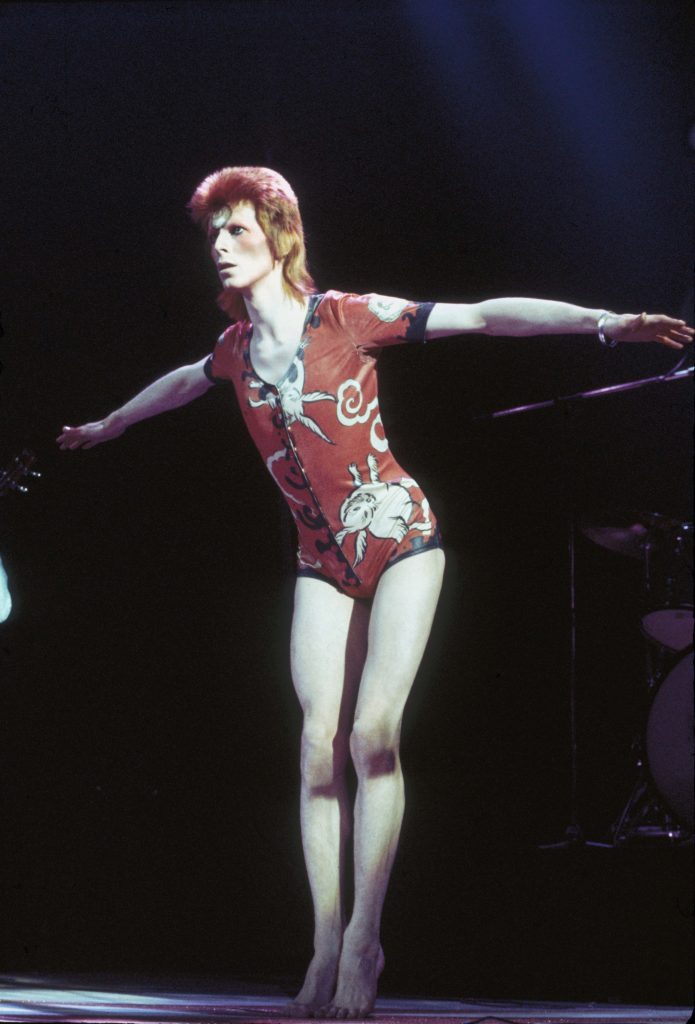

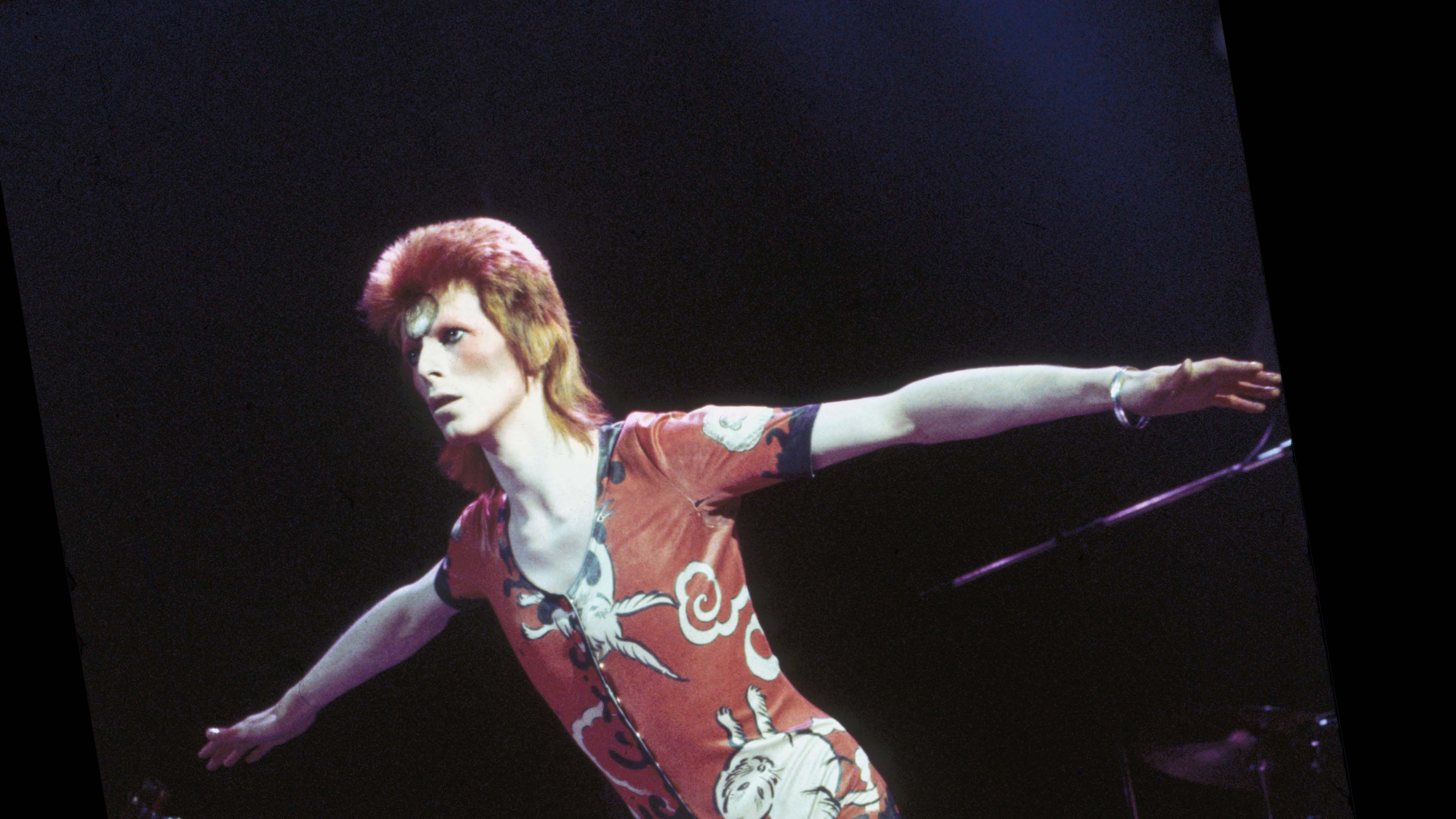

Appearing on the 1971 cover of The Man Who Sold The World modelling a dress (‘a man’s dress,’ he explained) and aping Greta Garbo on his androgynous Hunky Dory cover portrait, Bowie’s sexual revolution attained an epiphany the following year. On 6 July 1972, Bowie as Ziggy Stardust – his new alter ego, ‘a leper Messiah’ from another planet, dressed in tight bodysuit, snakeskin boots and sporting a carrot-coloured hairdo – appeared performing ‘Starman’ on the weekly BBC TV show Top Of The Pops (TOTP).

The programme’s regular 10 million-plus viewers had witnessed nothing previously to compare with the seismic effect of this performance. Bowie draped himself around guitarist Mick Ronson and the pair closed in for a near kiss as they mouthed harmonies. When he eyed the camera, sang the line ‘I picked on you … hoo … hoo’ and pointed directly at millions of living-room bound teens, a compact between performer and audience was joined. The interplay with Ronson went further in Ziggy stage shows. The image was captured in full-page music press adverts of Bowie kneeling in front of Ronson, grabbing the guitarist’s buttocks as he played a short, orgasmic guitar solo.

That same year Bowie ‘came out’ in an interview with the Melody Maker declaring ‘I’m gay and always have been, even when I was David Jones’.

In the spectacle they evoked and worldviews they espoused Bowie songs now invited, even depended on, audience participation. Compositions such as ‘John, I’m Only Dancing’ – sung from the viewpoint of a bisexual narrator having a tiff with his gay lover – tore up the standard pop rule book, joyfully describing alternative ways of living.

In the years ahead Bowie would qualify his comments on sexual preference, telling Playboy magazine in 1976 that he was bisexual, stating in 1983 that he was really heterosexual, and, in 1993, explaining that though being gay ‘wasn’t something I was comfortable with … it had to be done’.

The point was that in Bowie’s world liberation, discovery and change were all welcomed, possible and even necessary to survive.

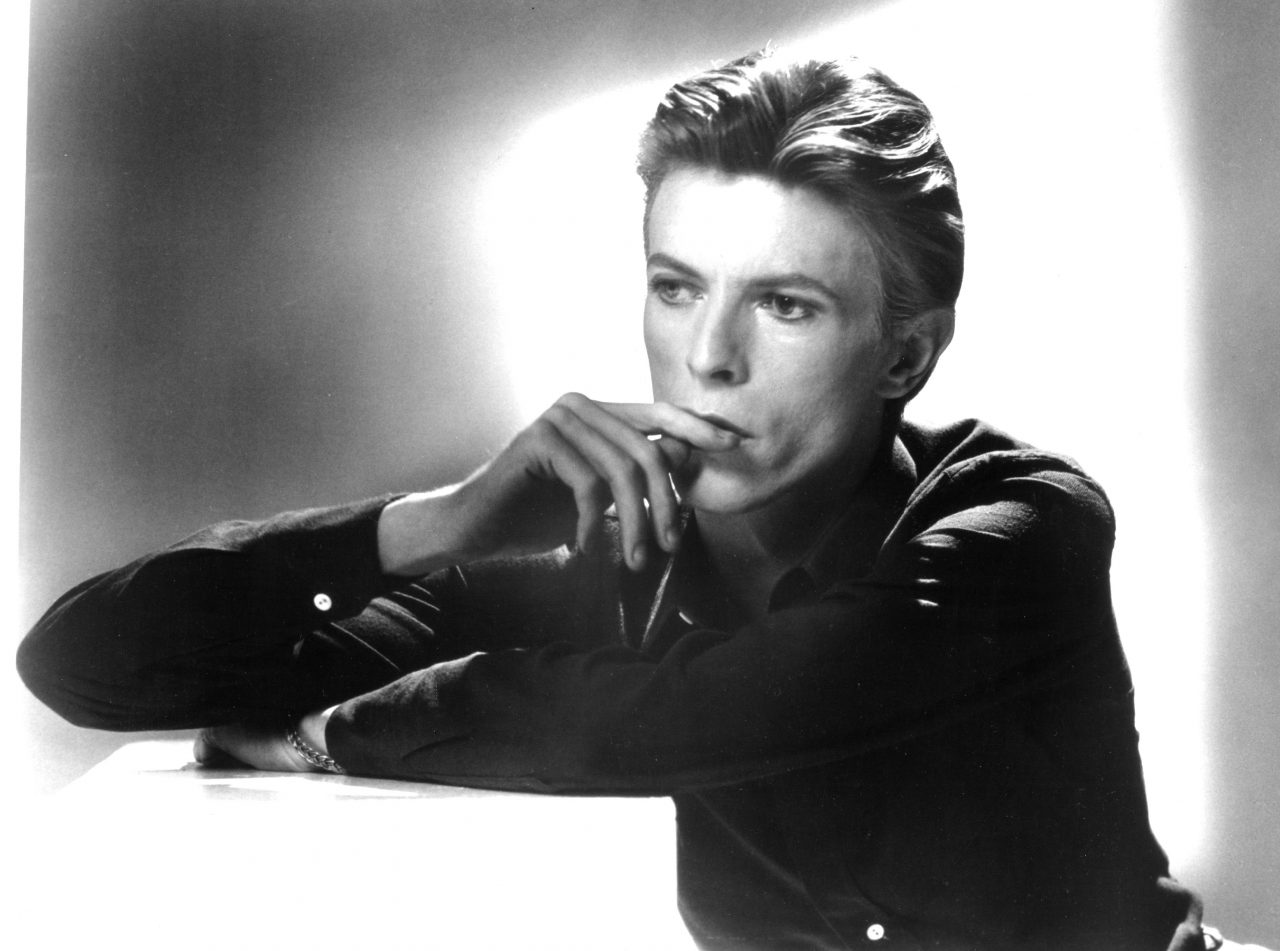

Ziggy was soon discarded, and with new musical statements and alter egos to carry them – Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, Plastic Soul, the Kraut Rock-inspired, electro pop pioneering Berlin trilogy – Bowie accelerated pop’s transformative power. Ever inclusive and inviting, in 1975, presenting a Grammy Award to Aretha Franklin, he coyly but pointedly addressed the audience as ‘ladies, gentlemen and …others’. This casual premonitory manner was innate, and so his influence in inspiring and shaping the music of the next decade was widespread. Androgynous female stars such as Annie Lennox, Grace Jones and Siouxsie Sioux, and openly gay, ‘gender bending’ male pop stars – Marc Almond, Boy George and Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood – were very much Bowie’s children.

In Berlin transgender cabaret artist Romy Haag became Bowie’s muse and sometime lover. What Bowie producer Tony Visconti described as her ‘Space Age Disco’ floor show inspired the transvestite characters Bowie played, with typical warm, good humour, in his 1979 ‘Boys Keep Swinging’ video.

Bowie’s potency as a shamanic instigator and cultural dynamo wavered in the years following. But his mark on popstars ran through generations, apparent in the image play utilised by artists as varied as Kate Bush, Madonna, Lady Gaga and Bono. A whole panoply of characters from his past returned to taunt him in a 2006 mineral water advert, and his alien and androgynous selves haunted the straight suburban character he played in the 2013 ‘Stars Are Out Tonight’ video.

Then, after putting his past career behind him with the all-encompassing ‘David Bowie Is… ’ travelling exhibition, and facing the real final frontier of certain death from terminal cancer diagnosis, Bowie enacted the most audacious farewell in music history with 2016’s Blackstar. Appearing as a preacher brandishing a black star-emblazoned Bible in the video for the title track, and as the disturbed Button Man character experiencing earthly torment as death closes in in the ‘Lazarus’ video, Bowie’s search for meaning in the ritual of identity shifts in pop performance was keenly accentuated with this final release.

Breaking the fourth wall, a trick learned from watching Anothony Newley’s revolutionary TV series Gurney Slade as a teen, he thumbed his nose and waggled his fingers at the audience as he said goodbye. This knowing and inclusive sense of fun, maintaining pop’s underlying shared pleasure principle in the face of death itself, hearkened back to the 1972 TOTP ‘Starman’ performance. It also bespoke a generous and imaginative spirit – one to hold onto, right down through the many ages of pop.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Gavin Martin

Gavin Martin has been a professional music critic since 1978. As a feature writer for NME, Uncut, The Independent, The Times and many other publications he interviewed musical legends such as Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone and James Brown. His profile on Michael Jackson appears in HanifKureishi’s The Faber Book of Pop and a piece on Frank Sinatra and Van Morrison in the US compendium Rock N Roll Is Here To Stay. Currently Music Critic at the Daily Mirror Martin explores his musical fascinations further performing spoken word pieces and hosting the live event Talking Musical Revolutions.