Byron and the Byronic hero: Translating Byron into Chinese

Kate Webb introduces Angela Carter’s Wise Children, which uses Shakespeare, carnival and Hollywood to challenge distinctions between high and low culture and explore the relationship between energy and disorder.

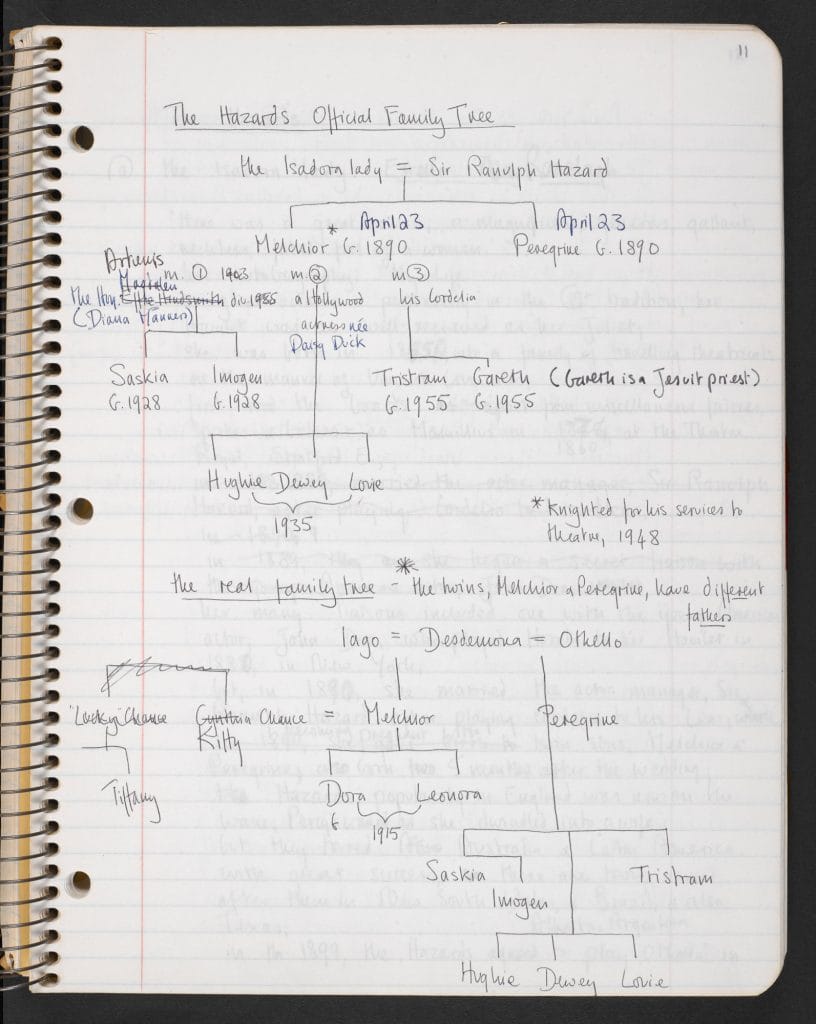

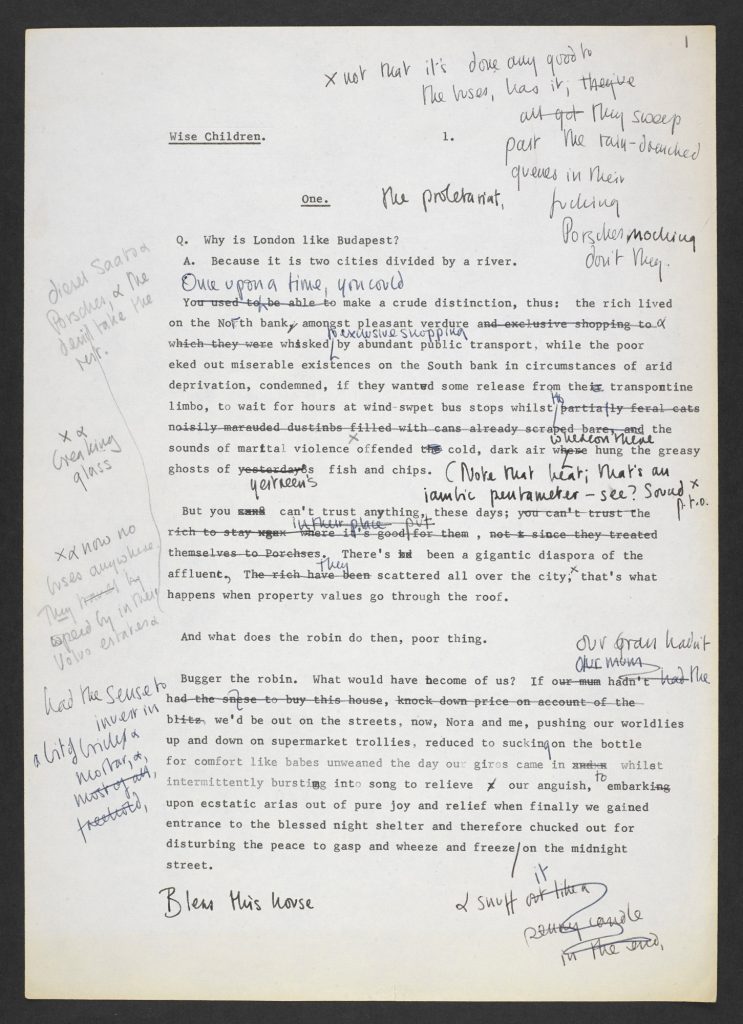

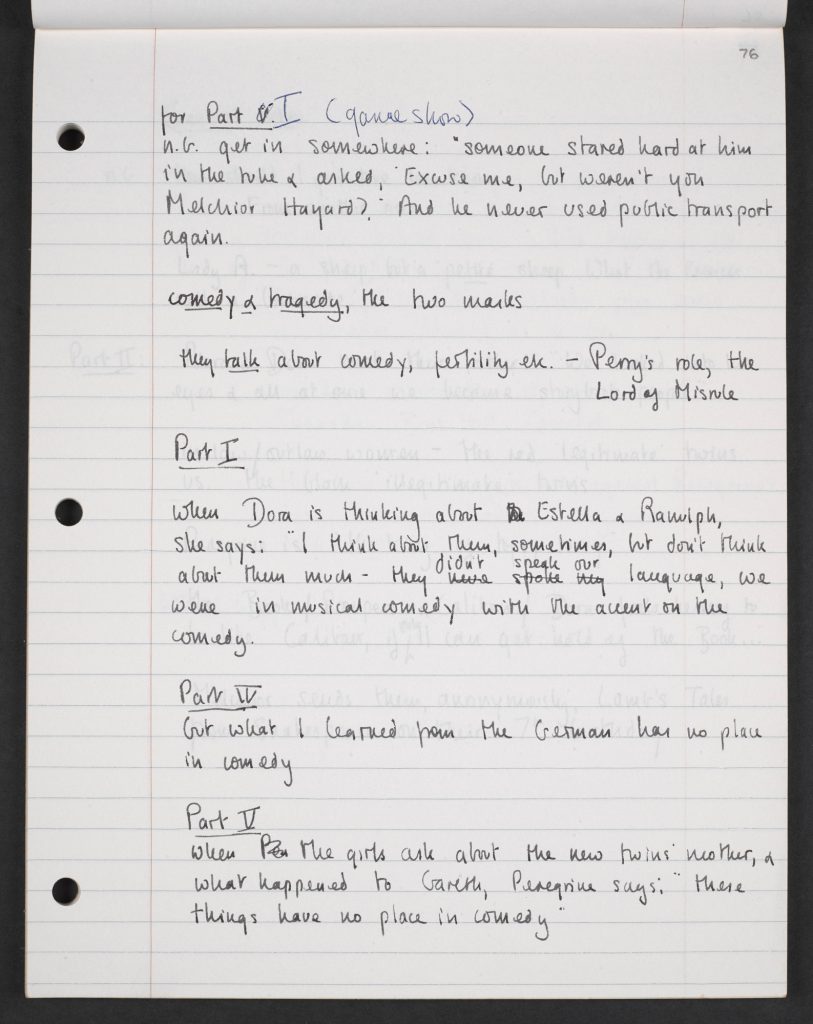

Wise Children, Angela Carter’s last book, published in 1991, is the story of the Hazard dynasty who ‘bestrode the British theatre like a colossus,’ and its bastard offspring, Dora and Nora Chance, identical twin girls who are illegitimate twice over: by birth, because their father denies his paternity of them time after time, and by profession, where, as a novelty act, they dance the boards in music hall, appear briefly as extras in an ill-fated Hollywood musical, and finally strip (though never beyond the G-string) in seedy post-war shows like ‘Nudes of the World’. The story is told by one of these lovely bastards, Dora, the wise-cracking, left-handed southside twin sister who rakes over more than a century of family romance and history. The action takes place in just one day – a special day, however: it is the anniversary of Shakespeare’s birthday, which happens also to be Dora and Nora’s own, their 75th. It is the birthday and centenary, too, of another set of twins, Melchior and Peregrine Hazard, father and uncle (but which is which?) of these performing sisters.

The double-faced Hazard/Chance family is served up to the reader as a model for Britain and Britishness, obsessively dividing itself into upper and working class, high and low culture. And just as Dora proves these strict lines of demarcation to be false within her own family, so, too, her story shows the reader how badly they fit the complexity and hybridity of British society and culture.

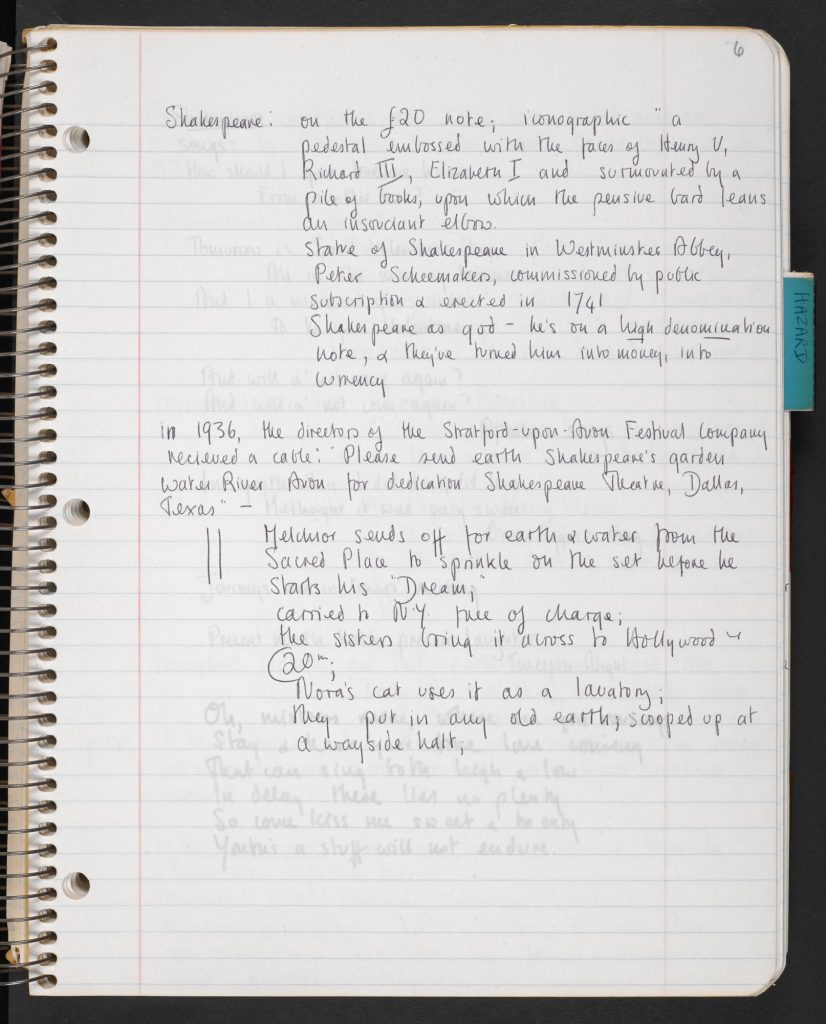

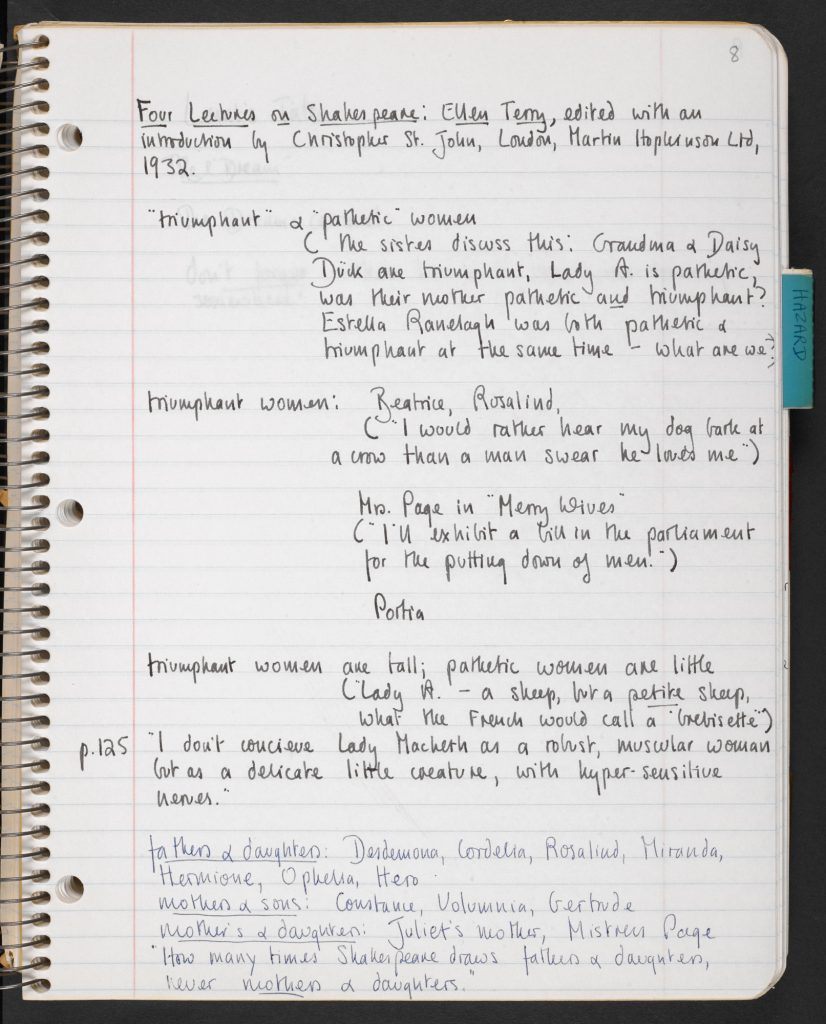

Master of these ideas is William Shakespeare, whose ‘huge overarching intellectual glory’ dominates the English literary canon and whose work, like Carter’s own, is brimful with ideas of doubleness, artifice and parody. In Wise Children Carter not only weaves Shakespeare’s stories in and out of her own, she also reminds us of the extent to which he impregnates British life and culture: his face is on the £20 note that Dora doles out to the fallen comic, Gorgeous George; and contemporary television programmes that poach their names from him like The Darling Buds of May, May to September and To the Manor Born, all make pointed, if somewhat disguised appearances in the novel.

Celebrating outcasts and illegitimates

Part of what attracts Carter to Shakespeare is his playing out of the magnetic relationship of attraction and repulsion that exists between energy and order. This occurs most famously, perhaps, in the sliding friendship of Prince Hal and Falstaff. Near the close of her story, Dora tries to reimagine one of Shakespeare’s cruellest moments: what if Hal, on becoming king, had not rejected Falstaff, but dug him in the ribs and offered him a job instead? What if order was permanently rejected and we lived life as a perpetual carnival?

Dora, illegitimate as she is, may sympathise with some of Falstaff’s bastard qualities, but her story is not one of martyrdom or victimhood. She knows that as outsiders she and her sister Nora are given freedoms for which their legitimate twin sisters, Imogen and Saskia, could never hope. When Dora describes Nora’s first sexual experience, she warns the reader not to

run away with the idea that it was a squalid, furtive miserable thing, to make love for the first time on a cold night in a back alley with a married man with strong drink on his breath. He was the one she wanted, warts and all, she would have him, by hook or by crook. She had a passion to know about Life, all its dirty corners, and this is how she started…(p. 81)

Wise Children, then, not only challenges order, it is also a celebration of the vitality of otherness. Paradoxically, though, because the legitimate and illegitimate world rely upon one another’s mirror image of difference through which to define themselves, such a celebration of illegitimacy necessarily implies a validation of the system which produces outcasts. Knowing this, one of the questions Carter asks us in the novel is: what, then, should a wise child do? Revel in wrong-sidedness and, therefore, the system that produces it, or reject the culture of dualism altogether? In answer, Carter’s wise – though now somewhat wizened – child, Dora, pulls off the sort of conjuring trick that her Falstaffian uncle Perry is famous for: she manages to sustain her opposition to authority, and yet to show that the culture and society she inhabits is not one of rigid demarcation, but has always been mixed up and hybrid. Shakespeare may have become the very symbol of legitimate culture, but his work is characterised by bastardy, multiplicity and incest; the Hazard dynasty may represent propriety and tradition but they, too, are an endlessly orphaned, errant and promiscuous bunch.

‘High’ culture: Shakespeare, royalty and empire

The patriarchs of the Hazard family find their authority deriving not from God, but from a Shakespeare who has come to seem all-powerful in British culture, to embody not only artistic feeling but religious and national spirit too. By becoming, each in his own generation, the ‘greatest living Shakespearean’, Ranulph and then Melchior assume a kingly status themselves. Having so often rehearsed the role of Shakespeareian prince or king, these actors adopt the role of royalty itself: ‘the Hazards … were a national treasure’.

Ranulph’s zeal for spreading the word of Shakespeare is so great that he travels ‘to the ends of the empire’ in his efforts to sell the religion of Shakespeare – his troupe’s ‘patched and ravaged tent went up in the spaces vacated by travelling evangelicals’. His ‘mission’ is to persuade people of the greatness of the Bard’s words, just as missionaries took the Bible and tried to persuade ‘natives’ of the truth of God’s Word. Mirroring the collapse of both empire and royalty, the ‘the Royal family of theatre’ appear as vulgar and commercialised as our latter-day House of Windsor. Like them, the Hazard dynasty has become a national sport, soap opera masquerading as news. Nonetheless this troupe performs in ‘wild, strange and various places,’ and their costumes are ‘begged or improvised or patched and darned’. Cultural hegemony may have been an important part of the imperial vision, but acting, Carter reminds us, has always been a bastard profession: peripatetic, thrown-together, made-up and sexually ambivalent – in Central Park, Estella plays Hamlet in drag. Theatre, and particularly the theatre of Shakespeare, has played its role in colonising the minds of other countries, but it is also a potentially destabilising and subversive force.

‘Low’ culture: Gorgeous George

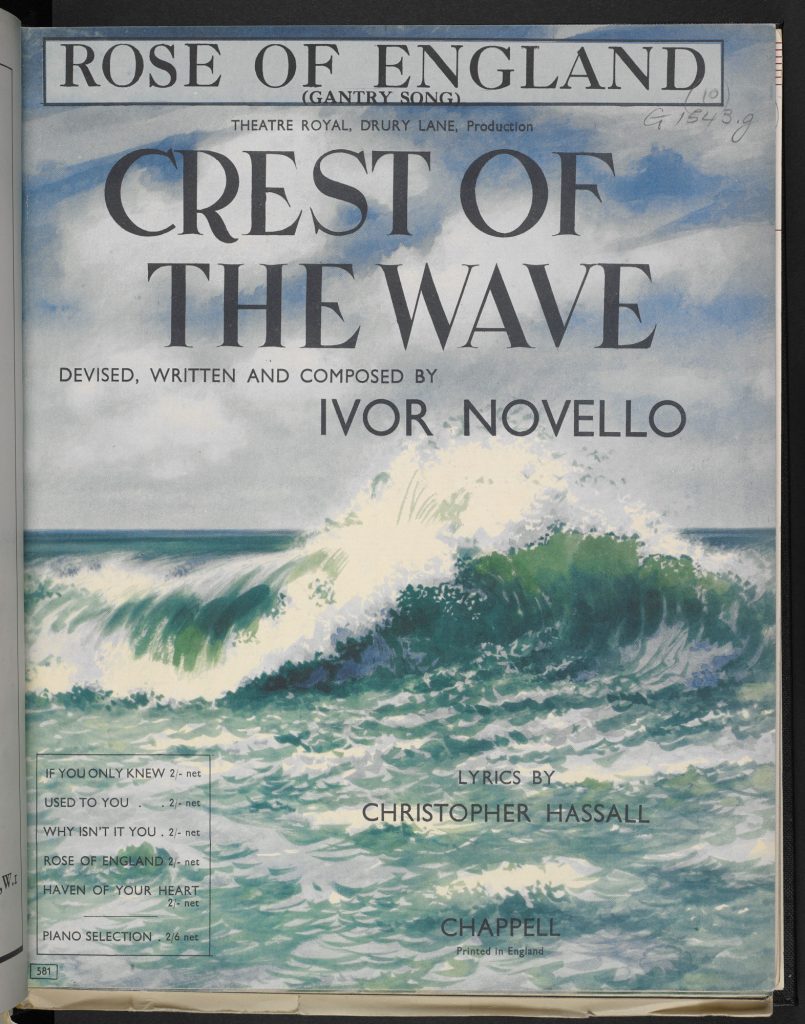

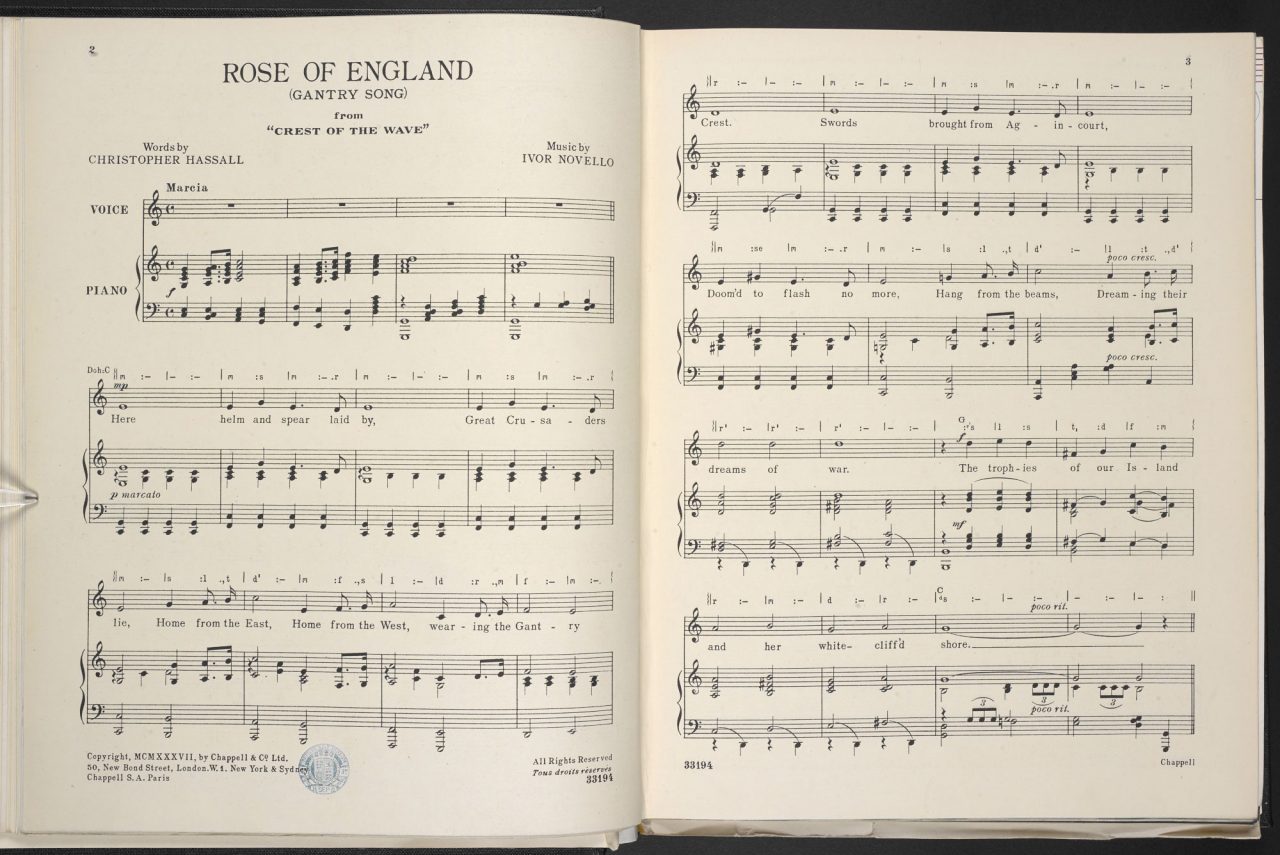

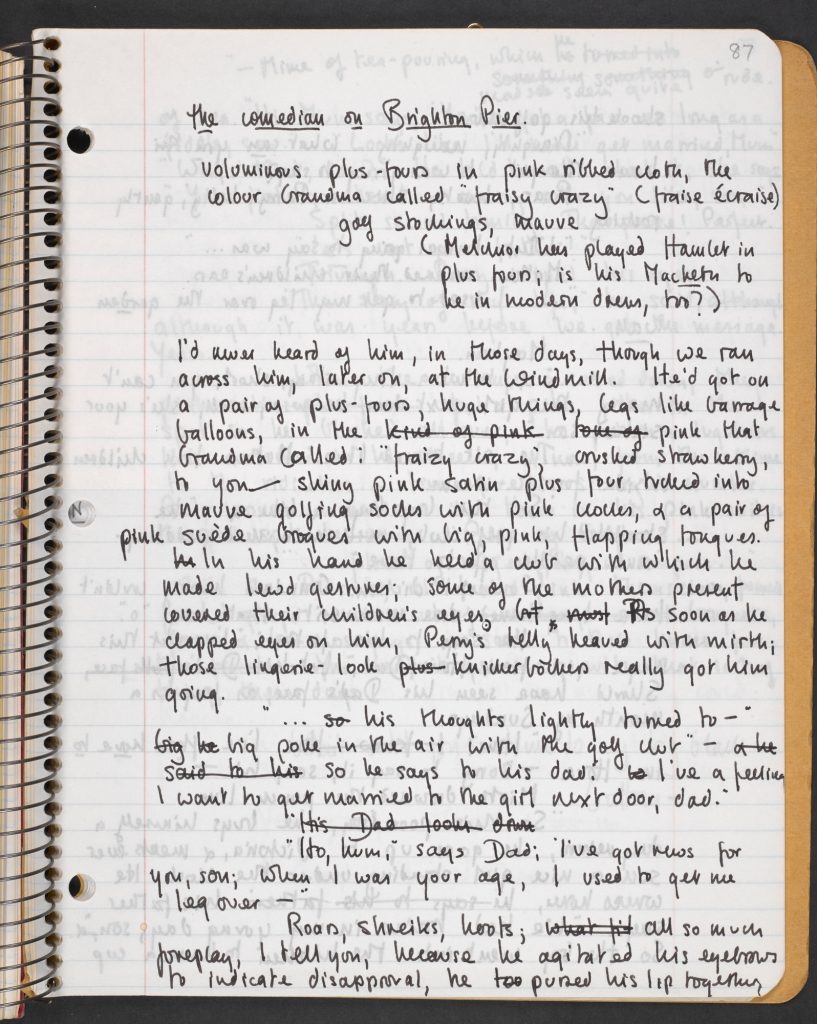

Dora first encounters the comic ‘Gorgeous George’ entertaining the people on Brighton pier. A combination of Max Miller, Frankie Howerd (‘Filthy minds, some of you have’) and Larry Grayson (‘Say no more’), he comes in the tradition of the holiday camp entertainer and his jokes are endlessly insinuating, every phrase carrying some double meaning. Sex is everywhere and with it, therefore, the possibility of incest. His coup de grâce, after singing ‘Rose of England’, ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’, is to strip off before his dazzled audience and reveal a torso tattooed with a map of the world: ‘George was not a comic at all but an enormous statement’. But even a statement as blatant as the pink- (for British colonies) dominated world, emblazoned across the body of this latter-day St George, is fraught with ambiguity. Unlike St George of old, Gorgeous George no longer rules the waves; he merely represents the idea of conquest. Having once dominated the world, this Englishman can now be master of only one space: his own body. George’s decline, like the British Empire’s, continues apace. Dora encounters him once more as Bottom in the Hollywood production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a debacle over which Melchior presides, and in which she and Nora have bit parts (they play Mustardseed and Peaseblossom). Finally, back in London, George ends up hitting rock bottom: Dora, catching a glimpse of his pink tattoo, recognises him as the pathetic street beggar who approaches her for the price of a cup of tea.

Fallen: Paradise Lost, Satan and Count Dracula

If Shakespeare provides English literary culture with a model for plurality, it is in Milton, particularly in Paradise Lost, that we find a model for dualism in the world, a dualism resulting from the patriarchal and monistic vision of Christianity. Another of Dora’s refrains is the Miltonic phrase, ‘Lo, how the mighty are fallen’, which is both a silly semantic joke and a serious intimation of the world she inhabits. Many of the descriptions of fallenness in Wise Children are specifically Miltonic: for instance, both Melchior and Peregrine are figured as godlike and satanic. Peregrine lands into the lives of the naked, innocent, unselfconscious and therefore Eve-like Nora and Dora as Adam arrived on earth: out of nowhere. And it is of Adam that Dora thinks when she sees him, because this is to be her First Man, the man who, like the fallen angel Lucifer, will first seduce her. In the same way Melchior, ‘our father’ who ‘did not live in heaven’ but who, god-like, is worshipped by the girls from afar, is also given a satanic side, appearing dressed in ‘a black evening cape with a scarlet lining’. Later he is Count Dracula (a late 19th-century satanic pretender), ordering Dora and Nora to carry dirt over from Stratford – as Dracula had carried it from Transylvania – to scatter on the Hollywood set of his film of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Hollywood and music hall

Like any postmodern novel worth its salt, Wise Children not only steals freely from other literary texts but also takes from the texts of other people’s lives and uses these too. In Hollywood, Carter has a field day. She has a roster of stars making guest appearances – sometimes as themselves, sometimes in various kinds of drag: featured players are Charlie Chaplin ‘hung like a horse’, Judy Garland (Ranulph’s wife is known as Estella ‘A Star Danced’ Hazard and was ‘born in a trunk’), Busby Berkeley, Fred Astaire and his wife Adele, Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Ruby Keeler, Jessie Mathews, Josephine Baker, Jack Warner, W C Fields, Gloria Swanson, Paul Robeson, Orson Welles (‘old buffers in…vintage port and miniature cigar commercials’), Clark Gable, Howard Hughes, Ivor Novello and Nöel Coward (Dora and Nora’s first dancing teacher is called Mrs Worthington), Daisy Duck with her missing back molars (it enhances the cheekbones) is a mixture of Lana Turner and Jean Harlow, ending up like Joan Crawford in TV soaps giving ‘good décolleté’. Daisy’s ‘peel me a prawn’ line is Mae West’s ‘Beulah, peel me a grape’ from I’m No Angel, and her Puck, with a ‘face like an old child’, is Mickey Rooney, who starred as Robin Goodfellow in the original model for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Erich von Stroheim is the model for Genghis Khan, the whip-cracking, jodhpured director with a penchant for cruelty and steak-eating orchids, and Dora’s alcoholic, scriptwriting boyfriend, Irish, is an amalgam of many writers – Scott Fitzgerald, Nathanael West and William Faulkner – finally succumbing to the abundant alcohol and indifference doled out in equal measures by the studio system. There’s a veiled portrait, too, of Brecht in Hollywood, whom Dora employs to teach her German and likes because he’s one of the few people she meets out there who aren’t terminally optimistic: ‘What I say is, fuck the bourgeoisie’.

Wise Children has songs, too: music hall and patriotic war songs, jazz and pop. And good and bad jokes: as well as Carter’s own (‘Why are they called Pierrots?’ … ‘Because they do their stuff on piers’), she pastiches older camp comedians like Frankie Howerd and Larry Grayson, and picks up on the more recent Thatcherite humour of Harry Enfield’s ‘Loadsamoney’, turning it into Tristram’s ghastly catchphrase ‘Lashings of Lolly’.

Writing methods

If her sources of material are eclectic, so too is her method of writing – Carter trips lightly through many styles and genres: she is an expressionist who paints ‘a female city, red-eyed, dressed in black’; a magical realist, a student of Hawthorne, Nabokov and Borges, wreathing Perry in magic butterflies; a graffitist scratching ‘Melchior slept here’ across her page; and a montage surrealist: ‘She was our air-raid shelter; she was our entertainment; she was our breast’. Carter is a conjuror baiting her audience – ‘All in good time I shall reveal to you how’; a romance novelist who knows where the big bucks are to be found – ‘Romantic illegitimacy. Always a seller’; a teller of tall tales – ‘If you believe that …’; and wise old wives’ tales. She’s also a re-teller of fairy stories – ‘Once upon a time…’/’It had come to pass…’ – an autobiographer and ‘inadvertent chronicler’, farceur and tragedian, fabulist and ‘rival realist’ – Sage’s phrase for Carter’s through-the-looking-glass world.

But just as this is a wise book, knowing about culture, history and politics, it is also a childlike one. The house at 49 Bard Road that Dora and Nora live in all their lives is reminiscent of the kind found in English children’s stories. Its large musty rooms and odd-striking grandfather clock, (mysteriously) absent father and mother and presiding grandmother left to eke out the rent by taking in strange boarders, are all staples of the genre. Orphaned children are free children – free of the sexually proscribing authority of their mum and dad, at least, so perhaps the (Wildean) habit of rather forgetfully losing your parents in these stories (as it patently is in Wise Children), is strategic: a way of allowing characters a little more space in which to fashion themselves.

Finally, as well as employing all these styles in her own writing, Carter shows us how a familiarity with many ways of seeing is a part of the modern condition: Dora is not only a passive observer of different genres, she also employs them to shape her own world. She does this to heighten experience, but also self-consciously, even paradoxically, to gain a sense of the constructedness of life by turning people into actors. For instance, when Estella leaves for America she imagines herself in a scene from a movie, and when Melchior, at the age of 12, absconds from the home of his ‘dour as hell’ puritan aunt, he does so as a character from a children’s story, as Dick Whittington.

The end

The sense of an ending, and later death itself, are strong presences in Wise Children – not just the end of empire or the death of the patriarch, which Dora is happy to let go – but the presence of death in the midst of life. Dora is someone who wrestles with this, a spirited fighter who refuses to grieve for long, or give in to defeat. ‘Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery,’ our autodidact narrator recites from Jane Austen. But one of Wise Children’s characteristic inversions of the supposed order of life is that no one dies of old age, all are ‘untimely deaths – the only true tragedy,’ Dora says wisely: most devastating of these, is the apparent death of their godchild, the young, mixed-race Tiff, who, Ophelia-like, seems to have made her suicide a watery one. But this is just one of the instances in which – to use Edward Said’s phrase – Carter ‘writes back’. Her Ophelia does not give in to patriarchal abuse (by committing suicide in Father Thames): rather she imagines herself as a new kind of being, and in the end it is she (the illegitimate outsider) who, having refused to be killed off by an old plot, lays down the new rules of play for the Hazard dynasty.

Pluralism and difference

In Wise Children, Carter is able to suggest a jumbled, impure multi-culture, while showing clearly that class, racial and sexual elites which seek to exclude otherness are still a powerful and conditioning force. By revealing Shakespeare at the heart of British culture, as the ‘author of our being’, father to both the Hazards and the Chances, Carter is arguing that plurality and hybridity are not simply conditions of modernity, products of its wreckage, but have always existed and are characteristic of life itself. From this it follows that she does not see in plurality, as many postmodernists do, a nihilistic loss of value; rather, she sees, an existential acceptance of the facts of life and death in which contradictions are a sign of hope, and difference has to be negotiated rather than fought over as if there were only one place of rightness, one correct way of living that must be identically reproduced the whole world over. This is something that Dora’s grandma knows innately – feels it, as Dora does, ‘in her ancient water’. When, in wartime, she waves her stick in the air at the bombers overhead, she recognises that war is a result of patriarchal insistence upon monism: men fight to wipe out women and children (because they are other); but forever locked in some recidivist Oedipal struggle, they fight, as well, to stop younger men stealing their thunder, to stop them taking away their distinguished mantles of poet or god.

‘A gallery of mirrors’

But while men continue to fight for absolute control of land or language, Carter tells us that we live now in a world of endless refraction. The days when a looking-glass reflected just one wicked witch, one absolute image of otherness, are gone. Now we have cinema, television, radio and video splintering the world ‘in a gallery of mirrors’, a glasshouse of perpetual reproduction. But these characters are not the glassy, fragile forms of some of her reworked fairy stories. Dora is a toughie, a survivor and a canny self-observer, and is not imprisoned by her female sexuality or the multitude of images of femininity that surround her. Rather, she seems like one of Shakespeare’s bastards, Edmund, determined not to let the Dionysian wheel of fate settle her life, but to find in the change of her wrong-sidedness neither shame nor restraint, but opportunity. Carter was one of the earliest writers to see that our relationship to these multiple, often contradictory reflections, can – especially for women – be as important and determining as our relationship to other people. Unsurprisingly then, the characters in Wise Children are equally mutating and promiscuous, often acting like the proverbial Freudian nightmare, aided and abetted (as Freud was himself) by Shakespearean example. This is why Dora’s family story is crammed with incestuous love and oedipal hatred. There are sexual relationships between parent and child (where this is not technically so, actor-parents marry their theatrical offspring – in two generations of Hazards, Lears marry Cordelias); and there is oedipal hatred (Ranulph ‘loved his boys. He cast them as princes in the tower as soon as they could toddle’).

‘What does a father do?’ and ‘what is he for?’

The question of paternity keeps arising in Wise Children. Just ‘what does a father do?’ and ‘what is he for?’ Dora asks. And well she might, given the example of the Hazard men, all of whom disown their children in one way or another. Ranulph leaves his twin sons Tristram and Gareth fatherless, abandoning them when he shoots their mother and himself in a lovers’ quarrel; Melchior and Peregrine, learning from Ranulph’s example, are equally forgetful about their fatherly responsibilities. Melchior forgets to love his children, and when he remembers, it’s the chilly, arm’s length affection that the wealthy inadequately bestow on their young. He denies paternity of Dora and Nora altogether, of course – the bastard girls he sired with his landlady one night in Brixton. (Perhaps the reason grandma creates a romance out of her origins and out of Dora and Nora’s is to protect them from their repudiating father, to allow them the freedom of making themselves up rather than being determined by Melchior’s dismissal.) His brother Peregrine, a lavisher of all kinds of love, while watching wistfully after Saskia (and this is ambivalent – are his feelings for her sexual or fatherly?), denies his paternity of both her and her twin sister Imogen.

What Carter hints at here is that it is the absence of practising fathers that causes so much grief and confusion: meaning that fathers, having never properly experienced fatherly feelings, often confuse them with sexual ones. In the same way, absent fathers are mysterious fathers, which is why these enigmatic creatures become, for their children, the object of such longing and romance. However, it is the errant behaviour of fathers that creates, among the Hazards and the Chances, so much opportunity for the breakdown of order. It seems that it is fatherly absence that creates the carnival. That men are such obstinately uncooperative parents stems from their carnival instincts, a sense of narcissism (Peregrine is far too self-involved to be able to give himself permanently as a parent); selfishness (Melchior is more interested in his work than in his children); and a desire not to be controlled or determined within a family order which limits the patriarch just as it confines women.

Such fatherly ambivalence, Carter suggests, might be rooted not only in carnival self-absorption but in the anxiety of paternity: the eternal ‘gigantic question mark over the question of their paternity’. It is this forever unresolved uncertainty about their role in biological creativity that has led men to create a mystique around artistic, and especially literary, creativity: as critics like Gilbert and Gubar have shown, the anxiety of paternity can be translated into the anxiety of authorship. In Wise Children, however, Carter argues that women, whose role in biological creativity is not in doubt (‘“Father” is a hypothesis but “mother” is a fact’), should now begin to shrug off the male anxiety that they, as writers, have been made to assume, and stop asking questions such as ‘Is the pen a phallus?’ Dora does not romanticise or transform sex into something other than it is, and she enjoys it for what it is. A straight-thinking woman, Dora would never mistake a pen for a penis.

Women, men and carnival

Although the Bakhtinian idea of carnival lies at the heart of Carter’s last novel, she suggests that women and carnival might, ultimately, be contradictory because female biology and the fact of motherhood make women an essentially connecting force, while carnival is essentially the celebration of transgression and breakdown. While some women in Wise Children possess characteristics that might be thought of as carnivalesque, it is a man, Peregrine, who embodies it: he is ‘not so much a man, more of a travelling carnival’. Peregrine is red and rude, and, in the classic Rabelaisian manner, a boundary-buster, growing bigger all the time. To Dora and Nora he is the proverbial rich American uncle, a sugar daddy whose fortunes dramatically rise and fall, but who, when he is in the money, spreads his bounty around with extravagance and enjoyment. He is a big bad wolf of an uncle, too, a randy old devil who seduces the pubescent Dora when she is just 13. He is a multiple man, and his multiplicity makes him as elusive as the butterflies he ends up pursuing as a lepidopterist in the Brazilian jungle: to Dora and Nora ‘He gave … all his histories, we could choose which ones we wanted – but they kept on changing so’.

Bringing the house down

More than this, Perry is a contradictory presence, a very ‘material ghost’, in whom Dora sees all her lovers pass by when, at the end of Wise Children, she and Perry are having sex for the last time (‘you remember the last time just like you remember the first’). She fantasises about what it would be like to bring the house down, to fuck it away in some glorious carnival orgy of destruction. But after toying with the idea, and sensing the excitement of exerting such eradicating (warlike) power, Dora decides that this is not something she wants to do, because although her historical house has sometimes been a place from which people have tried to eject her, it is also where her history lies. Bastard that Dora is, this is a house that she has built too. (That the house is a metaphor for the literary canon is quite clear. Should those left outside trash the house of fiction, or try to renovate it?)

For all Dora’s carnivalesque enthusiasm, she’s always been able to tell the difference between what is real and fake, between what is tragedy (untimely death) and what isn’t (a broken heart). In an interview in 1984 Angela Carter said that she was essentially ‘an old-fashioned feminist’; her preoccupations were with the material condition of women: ‘abortion law, access to further education, equal rights and the position of black women’. On pornography she said: ‘I don’t think it’s nearly as damaging as the effects of the capitalist system’. Dora, too, is of this materialist persuasion: ‘wars are facts we cannot f*ck away, Perry; nor laugh away either. Do you hear me Perry? No’. Perry cannot hear Dora because at some level the irrational, possibilising, illusion-making carnivaler cannot entertain the ordered, hard ‘real world’. But just as Dora would not throw away the historical house of order, she would not banish the chaos of the carnival either. Because it seems to her ‘as if f*cking itself were the origin of illusion,’ and in this carnival world of illusion there is the possibility to conceive of the world differently. There are ‘limits to the power of laughter’ – the carnival can’t rewrite history, undo the effects of war or alter what’s happening on the ‘news’. And there is no transcendence possible in life, Carter tells us, from the materiality of the moment, from the facts of oppression and war. But carnival does offer us the tantalising promise of how things might be in a future moment, if we altered the conditions which tie us down. It is only the carnival which can give us such imagined possibilities, which is why the creative things that make it up in life are so precious: laughter, sex and art.

Dora reports from both sides of the tracks, chronicling a history of exclusion and opposition, but also of wrong-sided exuberance. She ends her story, and her day, in charge of two new babies (carnival bringing newness into the world). As ever in the dialectical Hazard/Chance family, they turn out to be twins, but this time the old sexual divisions are broken, for this latest double act signals a change of direction – these wise children are ‘boy and girl, a new thing in our family’. And who knows where such a strange combination might lead? With this challenge, Angela Carter signed off. But if we attend, we can hear her out there riding Dora’s wind: ‘What a wind! Whooping and banging all along the street … The kind of wind that gets into the blood and drives you wild. Wild’.

© Kate Webb

撰稿人: Kate Webb

Kate Webb is a critic and editor, a regular reviewer for the TLS and the Spectator, her work has also appeared in The Guardian, The Observer and The Daily Telegraph. Her essays on Angela Carter and Christina Stead have been published by Macmillan, Virago and the Halstead Press.