Original manuscripts by five of the greatest writers in the English language will go on show in Shanghai for the first time in March 2018. ‘Where Great Writers Gather: Treasures of the British Library’ will feature drafts, correspondence and manuscripts by writers including Charlotte Brontë, D H Lawrence, Percy Bysshe Shelley, T S Eliot and Charles Dickens, alongside Chinese translations, adaptations and responses to their works.

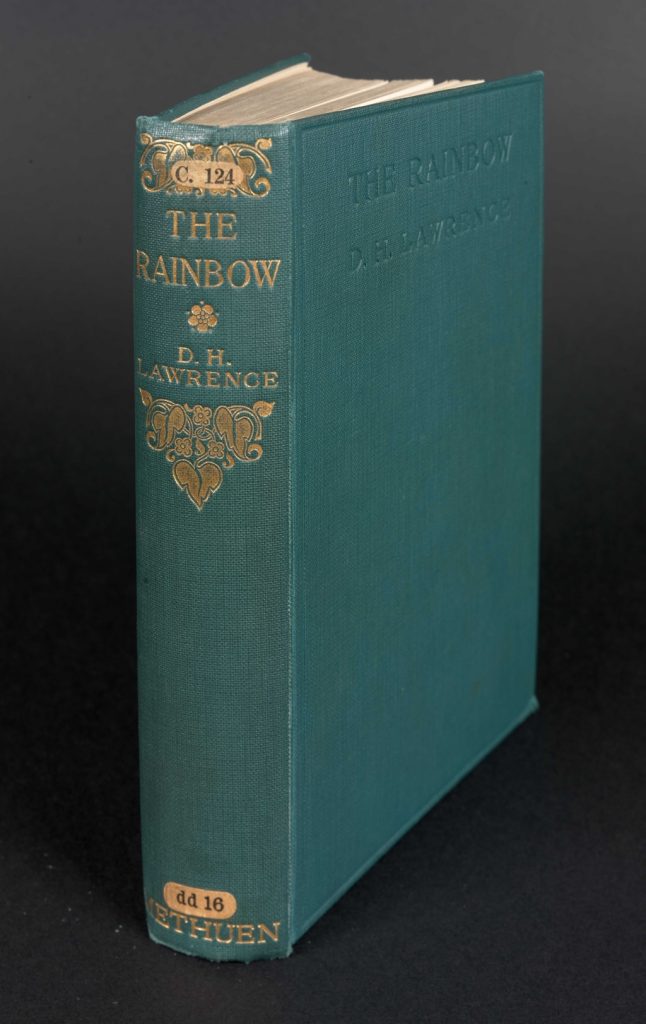

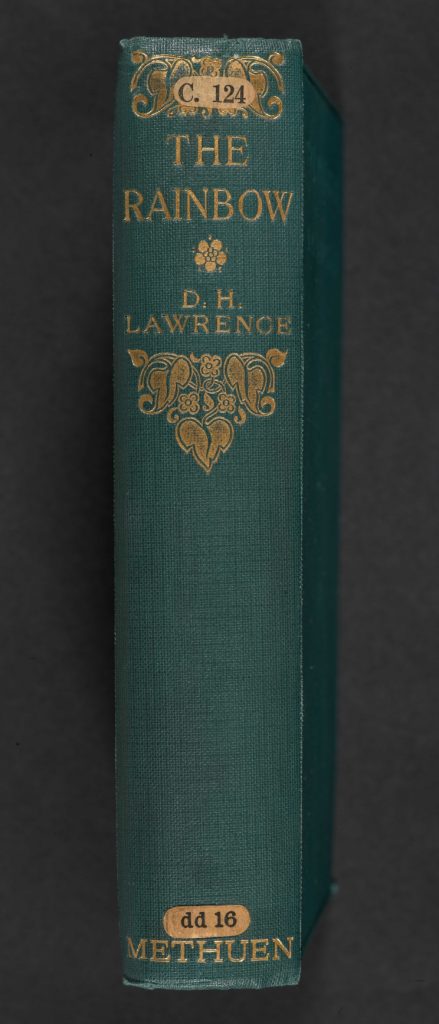

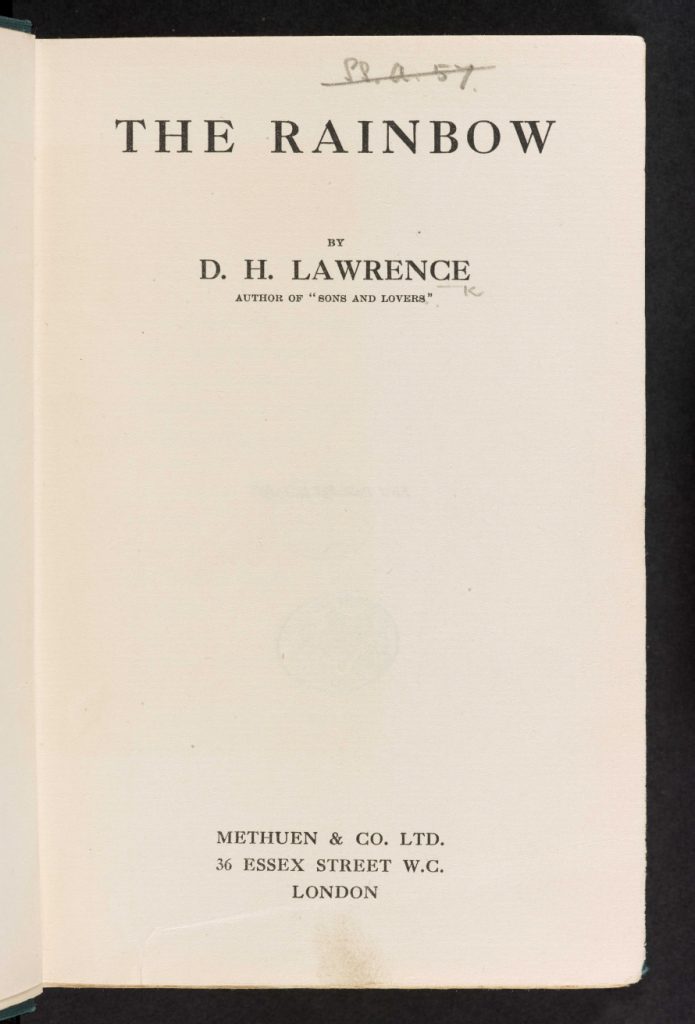

D H Lawrence’s The Rainbow

出版日期: 1915 文学时期: 20th Century 创建: 1913-1915

When D H Lawrence wrote The Rainbow between 1913 and 1915 he was a celebrated young writer on the basis of his autobiographical novel Sons and Lovers. However, The Rainbow is a departure from its realist predecessor: in its exploration of the unconscious, and of repeated patterns of experience over three generations, it belongs with the work of Joyce and Woolf as one of the great innovative novels of the modernist period. Lawrence’s hopes for it were shattered when it was banned for obscenity on publication, and it was not until several years later that it became widely available, by which time Lawrence had turned his back on the country that, he felt, had rejected him and his work.

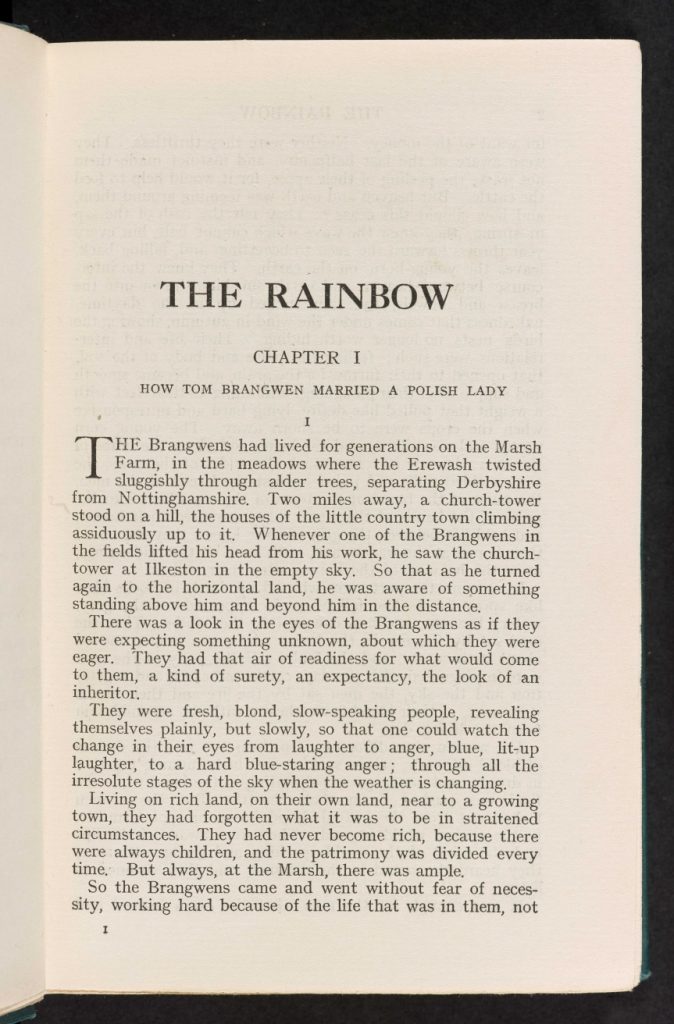

The Rainbow is D H Lawrence’s fourth novel, written between 1913 and 1915. It traces three generations of a family living on the border of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, in the north Midlands of England, where Lawrence himself grew up. He wrote it after the success of Sons and Lovers, an autobiographical novel about a coal-mining family. But the setting of The Rainbow is predominantly rural. At the beginning of the novel the Brangwen family are farmers, as they have been for generations. They are described collectively: ‘Then the men sat by the fire in the house where the women moved about with surety, and the limbs and the body of the men were impregnated with the day, cattle and earth and vegetation and the sky…’ (10). Through the generations the novel traces the emergence of the family from this immemorial life into modernity and increasing isolation. The process begins with the first major character, the farmer Tom Brangwen, who questions whether ‘he belonged to this world of Co ssethay and Ilkeston’ and marries a Polish woman (28). It ends with his grand-daughter Ursula who goes to university and becomes a teacher, but questions everything. She breaks her engagement with her first lover, a soldier, which would have bound her to a conventional life, and ends the novel facing ‘the unknown, the unexplored, the undiscovered upon whose shore she had landed, alone’ (457).

But the main difference between The Rainbow and Sons and Lovers is less one of setting than of literary method. Sons and Lovers is perhaps the last great English realist novel, following the nineteenth-century tradition of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy. However, when it was published Lawrence said that he would not write in that manner again, in what he called ‘that hard, violent style full of sensation and presentation’ (Letters 2, 132). He was developing a new style that was more internalised.

Although The Rainbow is a very long novel Lawrence’s original conception of it was even bigger. Eventually he divided it into two novels, The Rainbow itself and Women in Love (1920). Together these novels are regarded as Lawrence’s most important and most original. When he was working on them Lawrence wrote:

You mustn’t look in my novel for the old stable ego of the character. There is another ego, according to whose action the individual is unrecognisable, and passes through, as it were, allotropic states which it takes a deeper sense than any we’ve been used to exercise, to discover are states of the same single radically-unchanged element. (Like as diamond and coal are the same single pure element of carbon. The ordinary novel would trace the history of the diamond—but I say ‘diamond, what! This is carbon.’ And my diamond might be coal or soot, and my theme is carbon. (Letters 2, 183)

In displacing the ego and focussing on hidden aspects of the human subject, Lawrence is responding to contemporary developments in philosophy and psychology, above all psychoanalysis. He was also a pioneer in applying such ideas to the novel. He wrote The Rainbow and this letter several years before Virginia Woolf’s influential essay ‘Modern Fiction’, in which she accused popular contemporary novelists of ‘materialism’ because of their concentration on externals and argued that they should focus instead on the ‘unknown and uncircumscribed spirit’ of humanity.

This ‘other ego’ is explored in terms of bodily experience and the influence of nature. We see this in the courtship of the two main characters in the second generation, Tom and Anna. In this scene they are gathering sheaves of corn in a field in the moonlight. He wants them to meet so that he can embrace her, but she mysteriously resists this.

She stooped, she lifted the burden of sheaves, she turned her face to the dimness where he was, and went with her burden over the stubble. She hesitated, set down her sheaves, there was a swish and hiss of mingling oats, he was drawing near, and she must turn, again. And there was the flaring moon laying bare her bosom again, and making her drift and ebb like a wave….

There was only the moving to and fro in the moonlight, engrossed, the swinging in the silence, that was marked only by the splash of sheaves, and silence, and a splash of sheaves. And ever the splash of his sheaves broke swifter, beating up to hers, and ever the splash of her sheaves recurred monotonously, unchanging, and ever the splash of his sheaves beat nearer.

Till at last, they met at the shock, facing each other, sheaves in hand. And he was silvery with moonlight, with a moonlit, shadowy face that frightened her. (pp. 114–15)

This scene dramatises the undercurrent of feeling between two people who never achieve the perfect intimacy that they want. The sentence ‘And there was the flaring moon laying bare her bosom again, and making her drift and ebb like a wave’ epitomises the way feeling is expressed through the body and through connection with nature. The rhythm of the prose, especially in the second paragraph quoted, echoing the rhythms of nature and of bodily life, also contributes to the effect.

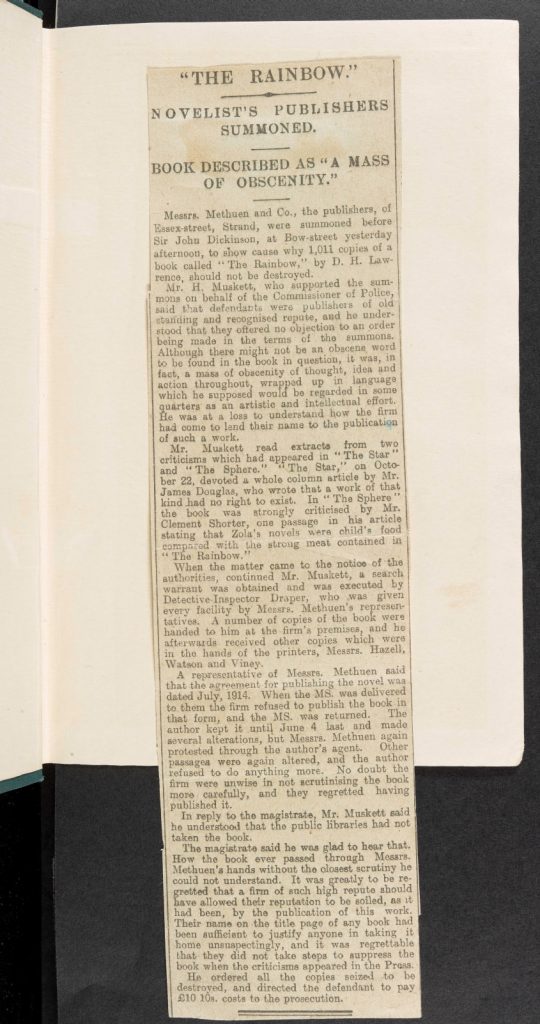

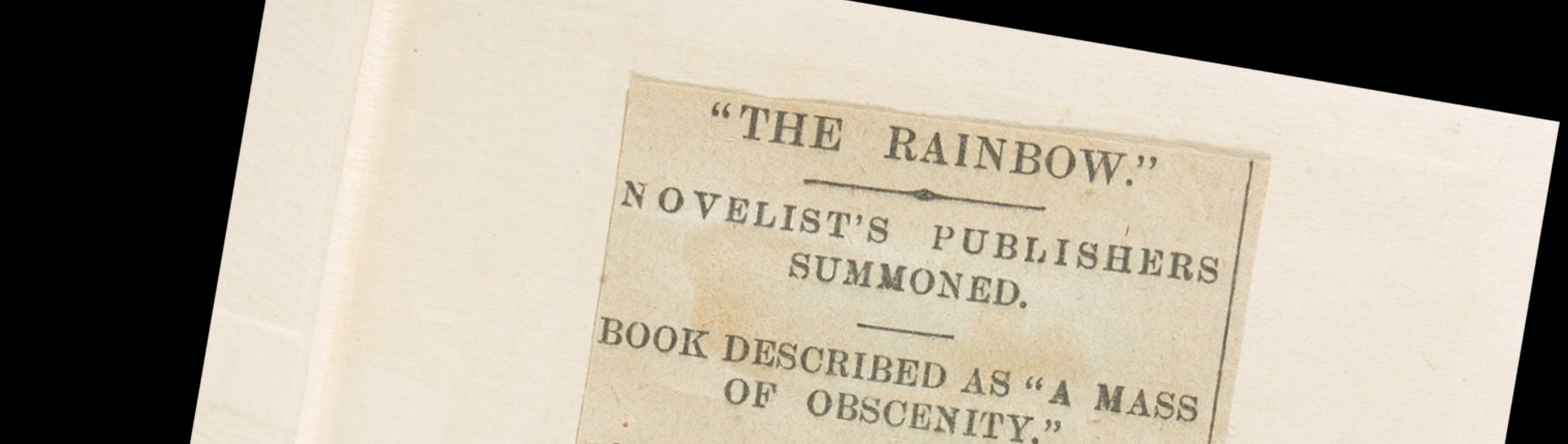

Censorship

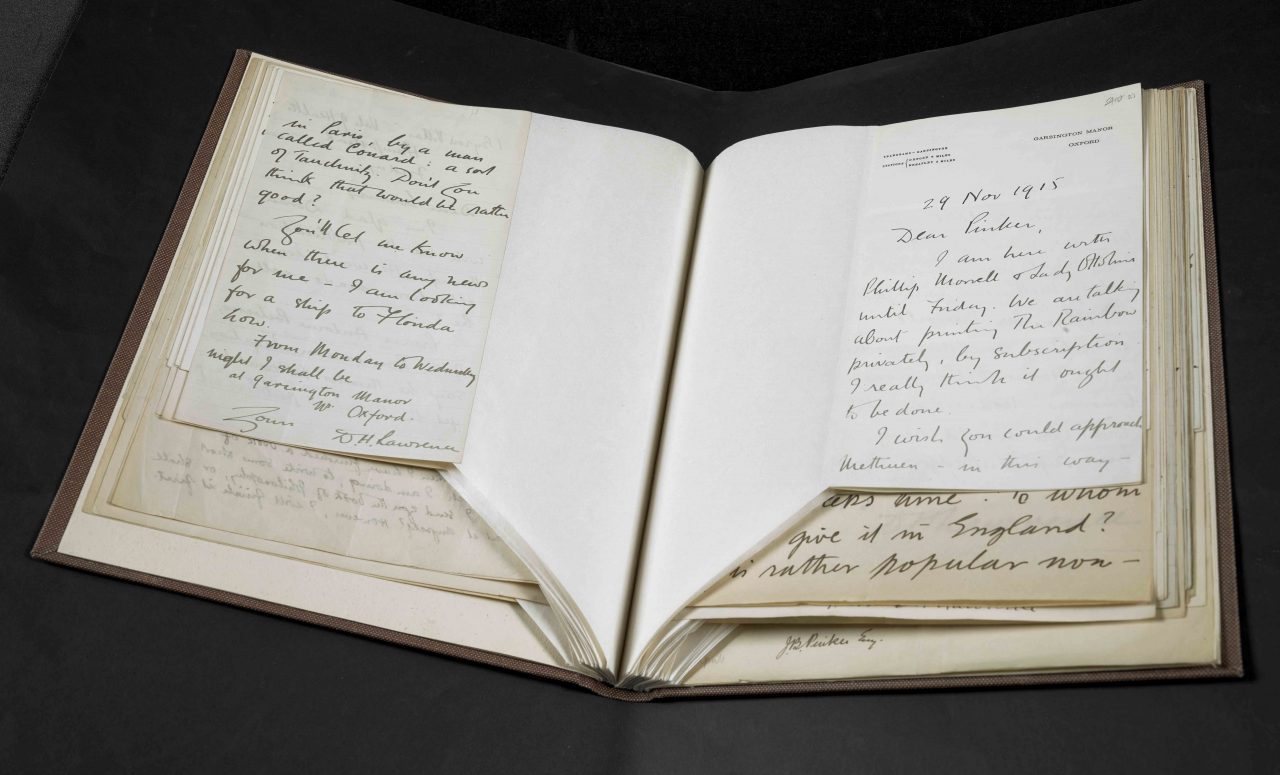

When The Rainbow was published in 1915 Lawrence had great hopes for it. He knew that it was his most important and original work so far. But he was struck a devastating blow when the novel was suppressed on the grounds of obscenity, and every available copy was destroyed. There is an episode in which the young Ursula has a lesbian affair with her teacher which may partly have accounted for the legal action. But there is also a strong anti-militaristic sentiment in the novel, which would have been regarded unfavourably at the height of the First World War. At one point Ursula says to her soldier-lover, ‘I hate soldiers, they are stiff and wooden’ (p. 289), and later, when he talks about going to serve in India, she says ‘you’ll feel so righteous, governing them for their own good. Who are you, to feel righteous? What are you righteous about, in your governing? Your governing stinks. What do you govern for, but to make things there as dead and mean as they are here?’ (pp. 427–28). One of the reviewers, who may have influenced the legal prosecution, wrote, ‘A thing like The Rainbow has no right to exist in the wind of war’.

The Rainbow ends on a note of optimism: ‘She saw in the rainbow the earth’s new architecture, the old, brittle corruption of houses and factories swept away, the world built up in a living fabric of Truth, fitting to the over-arching heaven’ (p. 459). Yet the suppression of the book ensured that Lawrence was never to be as optimistic again. He endured serious poverty throughout the war, and the sequel to The Rainbow, Women in Love, was not published for another five years. After the war he left England as soon as he could, turning his back on the country of his birth and spending nearly all the rest of his life abroad.

Contributor: Neil Roberts

Professor Neil Roberts is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield. His main interests are in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature. He is the author of Ted Hughes: A Literary Life; D.H. Lawrence, Travel and Cultural Difference; and A Lucid Dreamer: The Life of Peter Redgrove as well as books on George Eliot, George Meredith and contemporary poetry. His latest book, Sons and Lovers: The Biography of a Novel, was published in 2016.