Incantations of Joy, Hope and Love: The Translation and Reception of Percy Bysshe Shelley in China

This article tells the story of the translation and the reception history of Percy Bysshe Shelley in China since he was first introduced to Chinese readers in 1902.

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither’d leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish’d hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken’d earth

These two stanzas are from the last canto of ‘Ode to the West Wind’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), a poem written in 1819. Shelley’s ‘dead thoughts’ (as in deadly and revolutionary) did indeed trek thousands of miles halfway around the world to reach China and help quicken a new birth, although it took more than 100 years for them to do so.

Icon, iconic and iconoclastic

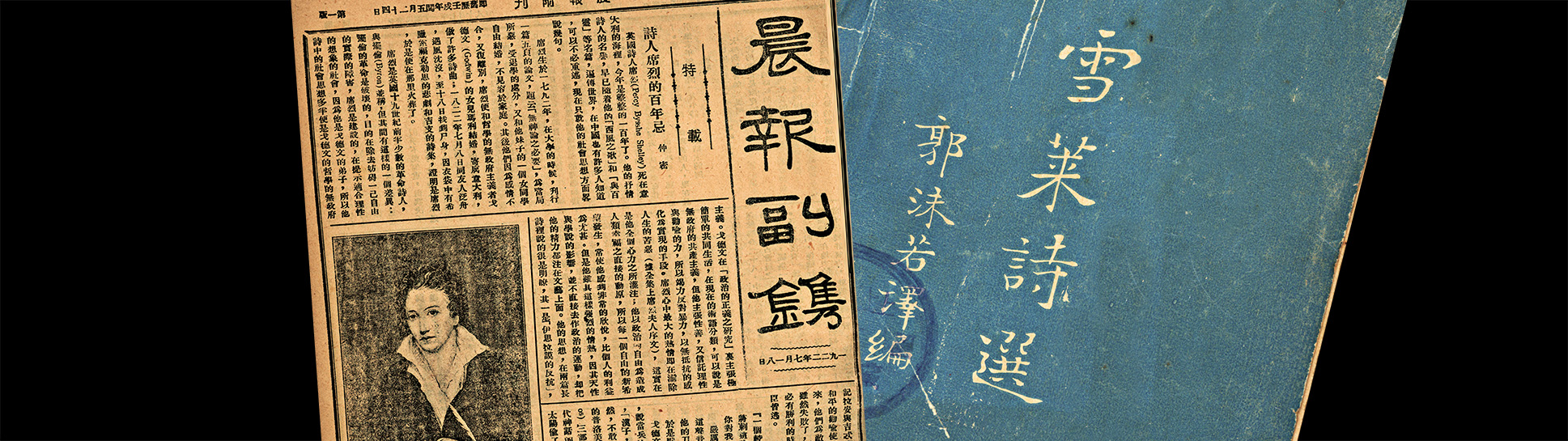

In 1902, just two years into the 20th century, Shelley finally landed in China, albeit represented by a portrait (based on a drawing by Shelley’s friend Amelia Curran) published in the second issue of New Fiction (小说月报), a literary magazine founded by Liang Qichao (梁启超 1873–1929) to promote sociopolitical reform by way of the exclusive publication of new fictional works. The same iconic portrait of the poet would reappear in a 1905 issue of the magazine and in other Chinese publications.

Ever since, incantations such as ‘If Winter comes, Can spring be far behind’ have given many Chinese the joy of hope, even in the darkest hours. Among those who have heard xuelai (雪莱), ‘trumpet of prophecy’ and ‘blithe spirit’, was Xi Jinping (习近平), a zhiqing (sent-down youth) during the 1970s, who would become the paramount leader of China in 2012 and even today still counts xuelai as one of his favourite Western authors. In fact, odd lines from Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’, ‘To a Skylark’ and ‘The Cloud’ would at least ring a bell with almost all college-educated Chinese, even if they have not actually read or tried to commit to memory these wildly popular lyrics in English or Chinese translations. Longer works such as Adonaïs, Prometheus Unbound, The Cenci and The Revolt of Islam have all received their share of attention too. Shelley may not quite be one of the greatest Western authors known in China – in the league of Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Dante – but he is certainly one of the best known and most iconic, a lofty position he initially reached during the first half of the 20th century.

One of the earliest among the Chinese who saw in Shelley a prophet of hope was Lu Xun (鲁迅1881–1936), a standard-bearer of the New Culture moment in the early decades of the 20th century. While still studying in Japan (he was there between 1902 and 1909), Lu Xun penned his well-known essay ‘Moluo shili shuo’ (摩罗诗力说), a sort of literary manifesto published in June 1907. In this essay, written in classical Chinese (文言文), Lu Xun reviewed the ancient civilisations of India, Egypt and Iran that had collapsed because they had basked in their past glories for too long and hadn’t continued to evolve and develop, and lamented the similarly pitiable plight that China found itself in. He went on to explain why he had borrowed the term ‘Mara’ (‘celestial demon’) from India, a term which meant Satanic or Byronic hero in Europe:

I apply it to those, among all the poets, who were committed to resistance, whose purpose was action but who were little loved by their age, and I introduce their words, deeds, ideas, and the impact of their circles, from the sovereign Byron to a Magyar (Hungarian) man of letters. Each of the group had distinctive features and made his nation’s qualities splendid, but their general bent was the same: few would create conformist harmonies, but they’d blow an audience to its feet, these iconoclasts, whose spirit struck deep chords in later generations, extending to infinity.

Lu Xun saw Shelley as a representative ‘Mara’ poet who died at the young age of 30, but lived an amazing life of poetry, free spirit and defiance: ‘as the world did not love him, so he did not love the world; as others did not tolerate him, so he did not tolerate others’. For Lu Xun, Shelley stood for the spirit of justice, liberty, truth and love, as embodied in The Revolt of Islam, Prometheus Unbound and The Cenci, which was urgently needed in China to ‘quicken a new birth’, to inspire cultural and spiritual enlightenment.

Guo Moruo (郭沫若1892–1978) was another leading figure on the cultural and literary front in China in the early 20th century who also appreciated the fighting spirit he saw in Shelley’s poems. Guo translated the last stanza of Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy, a poem written in 1819 about the infamous Peterloo Massacre (the killing of protesters who were seeking parliamentary reform in Britain):

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number –

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are many – they are few.

He wanted to borrow this stanza ‘to roar to the compatriots of the Republic of China shackled and suffering in these troubled times’. Guo counted Shelley as one of the most important sources of inspiration in his three phases of growth as a poet:

Fermenting Phase: Tang poetry

Awakening Phase: Tagore and Heine

Erupting Phase: Whitman and Shelley

In the eyes of Guo Moruo, Shelley was ‘a favorite son of Nature, a firm believer in Pantheism, a valiant fighter in Revolution. His poetry is his life and his life is a beautiful, perfect poem’. For Guo, translating Shelley meant transforming himself, so ‘I could become Shelley and so Shelley would become me’. Anyone who has read Guo’s Nüshen (女神 The Goddesses 1919–21) would easily see and feel the Shelleyan spirit pulsing through every line of the poems in this trailblazing collection.

Translating Shelley

The Chinese admiration of Shelley as an iconic and iconoclastic figure, a harbinger of hope and a new age in the early 20th century, led to many translations of his poems.

Around the time when he was writing his own radical poems, Guo Moruo was translating Shelley, too. For a 1923 ‘Shelley’ special issue of Chuangzao jikan (创造季刊 Creation Quarterly), a magazine founded by Guo and a few Chuangzao she (创造社 Creation Society) kindred spirits in 1922 to promote a new kind of literature, Guo wrote a biography of Shelley and translated seven of his lyrics, among them ‘Ode to the West Wind’, ‘To a Skylark’, ‘Invocation to Misery’, ‘Mutability’, and ‘Death’. These and a few other popular lyrical poems by Shelley, such as ‘The Cloud’, ‘Love’s Philosophy’ and ‘To the Moon’, would be translated over and over again because they channelled the passions of their translators. As Guo Moruo put it:

I love Shelley; I can hear his heart; I can resonate with him; I am married to him and have become one with him; his poems feel like my own; translating his poems feels exactly like writing my own poems.

Of course this doesn’t mean that all of Shelley’s admirers would translate his poems in exactly the same Chinese form or style. For example, Guo Moruo translated the opening stanzas of ‘To a Skylark’ in a classic wuyan (five-character) verse form:

Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert,

Bird thou never wert,

That from Heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.

In the golden lightning

Of the sunken sun,

O’er which clouds are bright’ning,

Thou dost float and run;

Like an unbodied joy whose race is just begun.

….

欢乐之灵乎!汝非禽羽族!

远自天之郊,倾斜汝胸膈

涓涓如泉涌,毫不费思索。

高飞复高飞,汝自地飞上

宛如一火云,振宇泛廖苍;

歌唱以翱翔,翱翔复歌唱!

For ‘Ode to the West Wind’ Guo switched to the relatively new vernacular (白话文):

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

哦,你不羁的西风哟,你秋神之呼吸,

你虽不可见,败叶被你吹飞,

好像罔雨之群在诅咒之前逃退,

黄者,黑者,苍白者,残红者。

无数病残者之大群: 哦,你,

你又催送一切的翅果去安眠

Not thrilled by this plain ‘prosaic’ rendition, which failed to capture the beauty and power of the original poem, Tian Shichang (田世昌), a contemporary of Guo’s and also an ardent Shelley translator, gave this poem a distinctively different Chinese rendition, in the style of ‘Li Sao’ (离骚) and Nine Songs (九歌) by Qu Yuan (屈原c. 340–278 BC). [1]

Differences between the two renditions – what is gained and what is lost – are readily apparent for anyone to see. Tian also used classic verse forms (e.g. five-character and seven-character) to translate quite a few of Shelley’s other poems.

Another ardent Shelley enthusiast in the early decades of the 20th century was Su Manshu (苏曼殊 1884–1917), a gifted and prolific poet, painter and translator (his work includes renditions of Byron’s poems and Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables). Su had wanted to translate Shelley’s poems contained in the copy of a collection re-gifted to him, but somehow he couldn’t get started. So he wrote a poem to express his tender, apologetic sentiments towards the poems and more tellingly towards the original gifter, a young English woman:

Someone gifted me Shelley’s poem,

Woe is me deep in emotional disarray,

To repay kindness I could find no way,

Only to see our eyes meet in my dream.

Su did eventually get to translate a few of Shelley poems, including ‘The Sensitive Plant’ (《含羞草》), which has 28 four-line stanzas. Unfortunately, only one of his translations was published posthumously and hence this is probably the sole example of his work that has survived in a widely available form:

A WIDOW bird sat mourning for her Love

Upon a wintry bough;

The frozen wind crept on above,

The freezing stream below.

There was no leaf upon the forest bare.

No flower upon the ground,

And little motion in the air

Except the mill-wheel’s sound.

冬日诗

孤鸟栖寒枝,悲鸣为其曹。

池水初结冰,冷风何萧萧!

荒林无宿叶,瘠土无卉苗。

万籁尽廖寂,唯闻喧挈皋。

In addition to the popular lyrical poems alluded to above, longer poems and dramatic verses by Shelley, such as Hellas, A Lyrical Drama, Prometheus Unbound, The Cenci and The Revolt of Islam, would soon receive Chinese renditions too. In 2000, a seven-volume Complete Works of Shelley (《雪莱全集》) was published.

Chinese Shelleys

Every now and then a Chinese poet has the honour of being called the ‘Chinese Shelley’ (中国的雪莱), but no one seems to deserve this honour more than Xu Zhimo (徐志摩 1897–1931), whose motto was to ‘to realize poetry in life’. Freshly returned from Cambridge in the UK in 1923, Xu declared in a lecture given in Beijing:

What on earth is a poet anyway? … The most exemplary poet of the poets (for me): Of the Chinese poets I love Li Bai (李白) the most; of foreign poets I love Shelley the most. The kind of life they each lived is a beautiful and perfect poem.

Xu proved to be true a Chinese Shelley, both in the life he lived and in the poems he wrote. As Hu Shi (胡适 1891–1962) said of him in a memorial piece: ‘His philosophy of life is truly “pure faith”, which has only three words: one is love; one is freedom, and one is beauty. His dream is to realise all three ideals in one lifetime’. In terms of the kind of poems Xu wrote, for example, one can definitely hear quite a bit of Shelley (as well as Whitman and Hardy) in his ‘Grey Life’ [‘灰色的人生’, 1923], which goes as follows (in English translation):

I want–I want to sing, at the top of my full-chested, hoarse voice, a bold, merciless, bone-chilling new song;

I want to rip open my long gown, my neat long gown, expose my chest, my belly, my ribcages and my veins;

I want to loosen up my long hair and let it hang wild on my shoulders like a wandering monk;

….

Come, let’s go to the sea and listen to the stormy waves shaking up heaven;

Come, let’s go to the mountains and listen to a sharp axe striking to fell an old tree;

Come, let’s go to the innermost chamber and listen to the disabled and desolate souls moaning;

….

Among others who have been called the ‘Chinese Shelley’ are Wu Mi (吴宓 1894–1978), a poet, writer, and one of the founders of Chinese comparative literature studies, and Chen Kui (陈逵 1902–1990), whom Wu Mi at one time called the ‘Chinese Shelley today’: ‘Those who know Shelley and love Shelley should know Chen Kui and love Chen Kui too’ because his poems are true poems in every sense of the term. In 1947, as anti-war, anti-hunger protests raged across the city of Shanghai and were being brutally put down by government troops, Chen Kui led his students at Fudan University in reading aloud Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’ in support of the protesters, chanting ‘If Winter comes, Can spring be far behind’. That is a very Shelleyan thing to do indeed.

Unrequited love?

Somehow, the ardent passion the Chinese have felt for Shelley feels not unlike ‘unrequited love’ because it was not reciprocated by Shelley. This disappointment has been duly noted by some Chinese scholars recently. In the preface to Hellas: A Lyrical Drama, for example, it has been pointed out that Shelley declares:

We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts, have their root in Greece. But for Greece – Rome, the instructor, the conqueror, the metropolis of our ancestors, would have spread no illumination with her arms, and we might still have been savages and idolaters; or, what is worse, might have arrived at such a stagnant and miserable state of social institution as China and Japan possess.

And the gods of ‘China, India, the Antarctic islands, and the native tribes of America’, Shelley goes on to say, are ‘monstrous objects of the idolatry’ and their evil reign would have continued but for the revival of Grecian learning and arts. For the Chinese, this hurts, naturally, although Shelley is far from alone among Western literary luminaries who have viewed China and other Eastern cultures as the despicable racial/cultural ‘Other’. After all, for Shelley and many others, who, understandably, hold a ‘Eurocentric’ view of the world, the fountainhead as well as epicentre of world civilisation is Occidental, Mediterranean, and more particularly, Hellenistic. In comparison, the China that Shelley knew of, the pre-Opium War (1839–41) China situated at the eastern-most end of the Eurasian land mass, didn’t seem to be well illuminated by exciting social, scientific and technological advancement at all.

Some Chinese have found comfort in a few obscure lines Shelley wrote about his love for tea-drinking (a habit the British had adopted from the Chinese in the 18th century):

The liquid doctors rail at, and that I will quaff in spite of them, and when I die we’ll toss up which died first of drinking tea.

Trying really hard to compensate on Shelley’s behalf perhaps, these Chinese have also taken a line from Byron’s Don Juan (唐璜), ‘Moved by the Chinese nymph of tears, Green Tea!’ (为中国之泪水——绿茶女神所感动), and put it in Shelley’s mouth, or rather, they have pretended that this Byronic line is the title of a Shelleyan poem paying tribute to something that originated from China.

Despite the few jarring, disharmonious notes he sounded about China, the Chinese love for Shelley remains steady to this day. Although times have changed dramatically from the decades of the early 20th century, and China has advanced light years away from the weak and underdeveloped country it used to be, Shelley’s incantations can still bring us the joy of hope and love. Reading Shelley today one can still feel awe-struck, and one can’t help wondering aloud and asking him, as Shelley himself does to the Skylark, that ‘[p]ourest thy full heart / In profuse strains of unpremeditated art’ while soaring heavenward:

Teach me half the gladness

That thy brain must know,

Such harmonious madness

From my lips would flow

The world should listen then, as I am listening now!

Note: This article draws from many Chinese and English sources, both print and electronic. All English translations of Chinese sources are mine.

The text in the article is © Dr Shouhua Qi. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Shouhua Qi

Dr. Shouhua Qi is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the College of Liberal Arts, Yangzhou University and Professor of English at Western Connecticut State University. Among Qi’s most recent publications are The Bronte Sisters in Other Wor(l)ds (coeditor and contributing author, 2014) and Western Literature in China and the Translation of a Nation (2012), both published by Palgrave MacMillan. Qi is working on a book titled Adapting Western Classics for the Chinese Stage (to be published by Routledge in 2018).

-1280x761.jpg)

-1280x947.jpg)

-707x1024.jpg)

-1280x963.jpg)

-669x1024.jpg)

-1206x1024.jpg)

-657x1024.jpg)

-710x1024.jpg)

-426x1024.jpg)

-1280x746.jpg)

-673x1024.jpg)

-1280x823.jpg)

-629x1024.jpg)

《冬日》(《潮音》,湖畔诗社,1925年)-648x1024.jpg)

(湖畔诗社,1925年)-717x1024.jpg)

-717x1024.jpg)

-675x1024.jpg)

-695x1024.jpg)

-630x1024.jpg)

-661x1024.jpg)