From the Thames to the Yellow River: The Translation and Reception of English Literature in China

From the earliest Chinese translations in the mid-1800s to the latest renditions in the 21st century, this article outlines the reception of English literature in China and its dynamic impact on modern Chinese cultural and literary life.

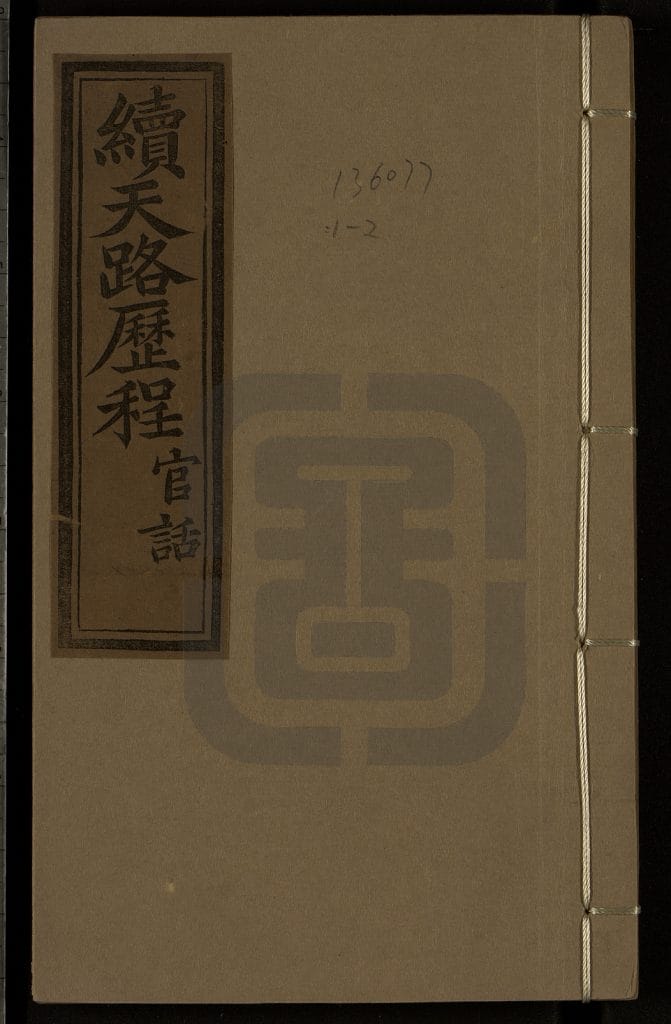

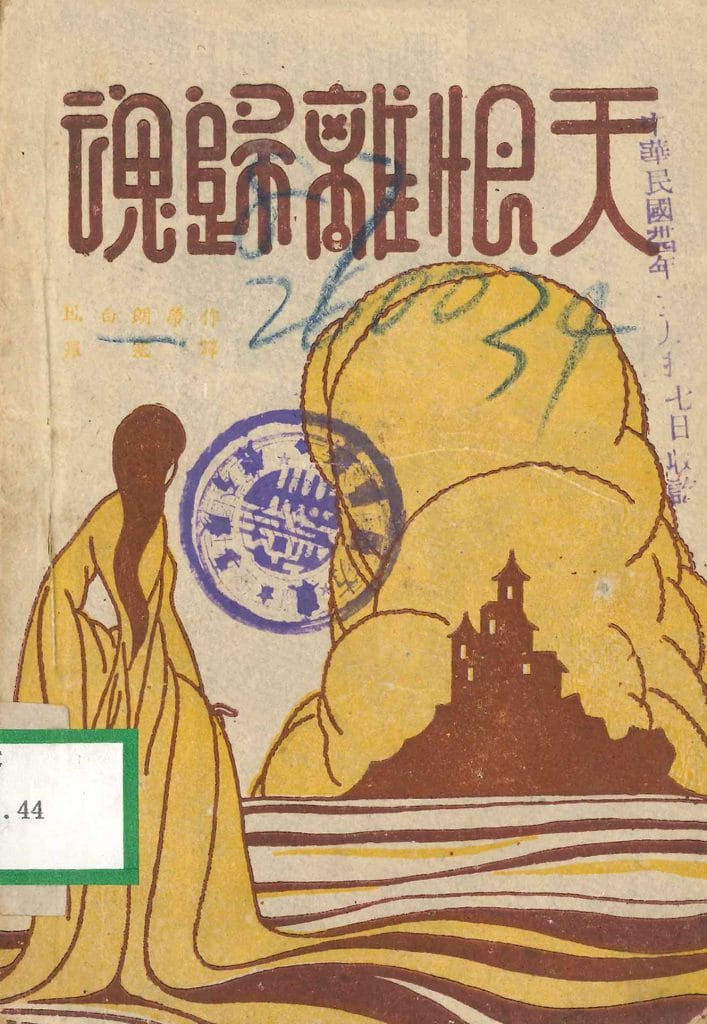

English literature probably first came to China by way of books packed in the luggage of early European merchants, missionaries and other travellers, along with their Bibles, The Travels of Marco Polo (c. 1300) and other stories that had been written about this mysterious land of splendid culture in the Orient. It was not until 1853, however, that the first Chinese translation of a work of English literature was published. It was The Pilgrim’s Progress [天路历程] by John Bunyan (1628–1688). The book generated so much interest that it had to be reprinted several times in just a few years to meet demand. In choosing this Christian allegory to render into Chinese (with, it should be noted, the assistance of a language informant), William Chalmers Burns (宾惠廉 1815–1868), a Scottish Presbyterian missionary in China, was probably more interested in spreading the Christian gospel than introducing English literature per se. Nonetheless, it was a taste of things to come, of the Chinese fascination with English literature that has been growing and deepening ever since.

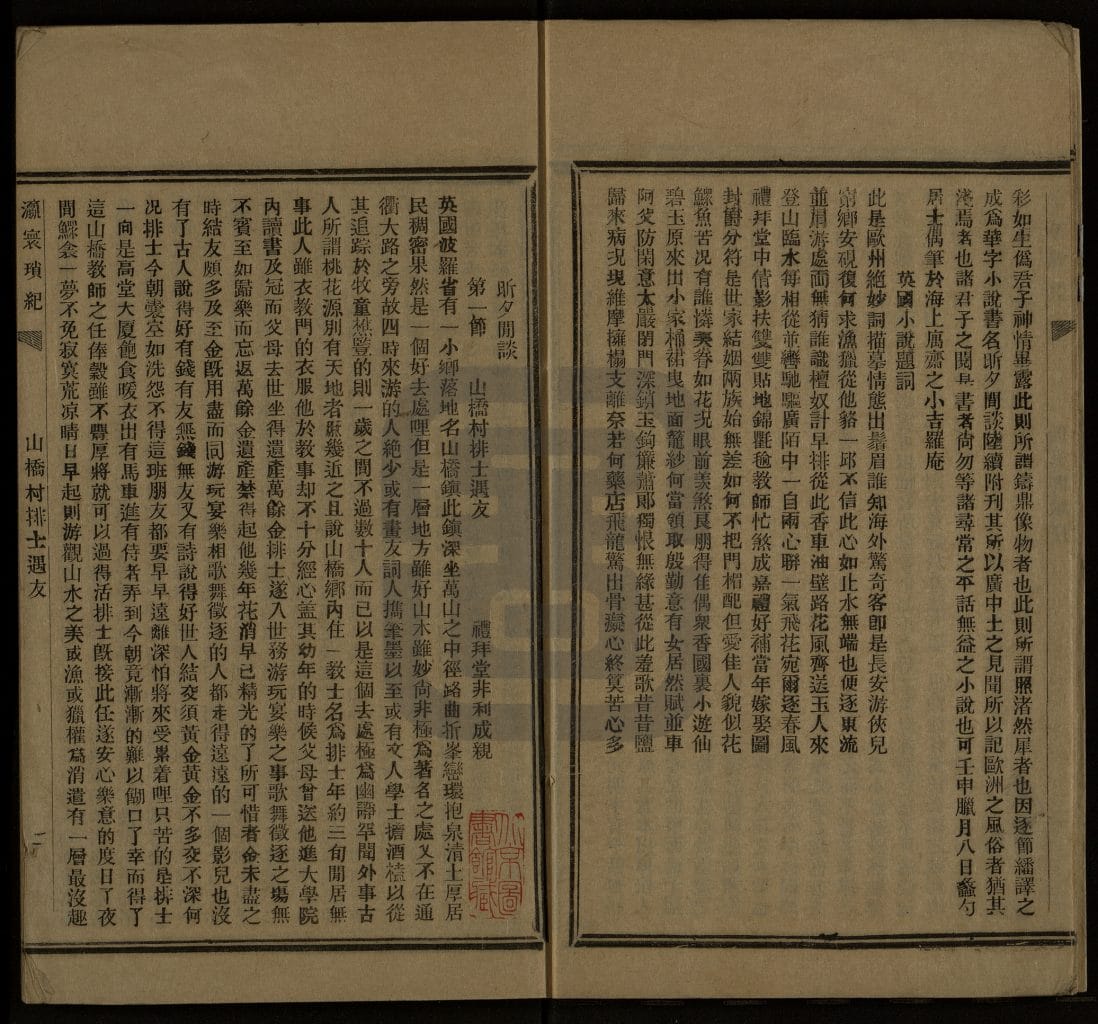

Night and Morning and the earliest works in translation

The first translation of a work of English literature by a Chinese did not happen until 1873. It was Night and Morning [昕夕闲谈], a novel by Edward Bulwer Lytton (1803–1873), who was immensely popular then and known for lines such as ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’. The Chinese translation was published in 25 instalments in a literary magazine. The translator (蠡勺居士 no known biography) chose this novel because it encouraged people to be good by exposing falsehood and hypocrisy. An edited edition of the translation was published in 1904 to help spread ideas of democracy in China. This fitted the ‘literature as a vehicle of the dao’ [文以载道] mantra upheld by the Chinese intelligentsia from time immemorial. It was indeed the search for dao, for ideas and ways to strengthen and save China in the post-Opium Wars (1839–42, 1856–60) brave new world, that inspired much of the interest in all things Western, including English literature.

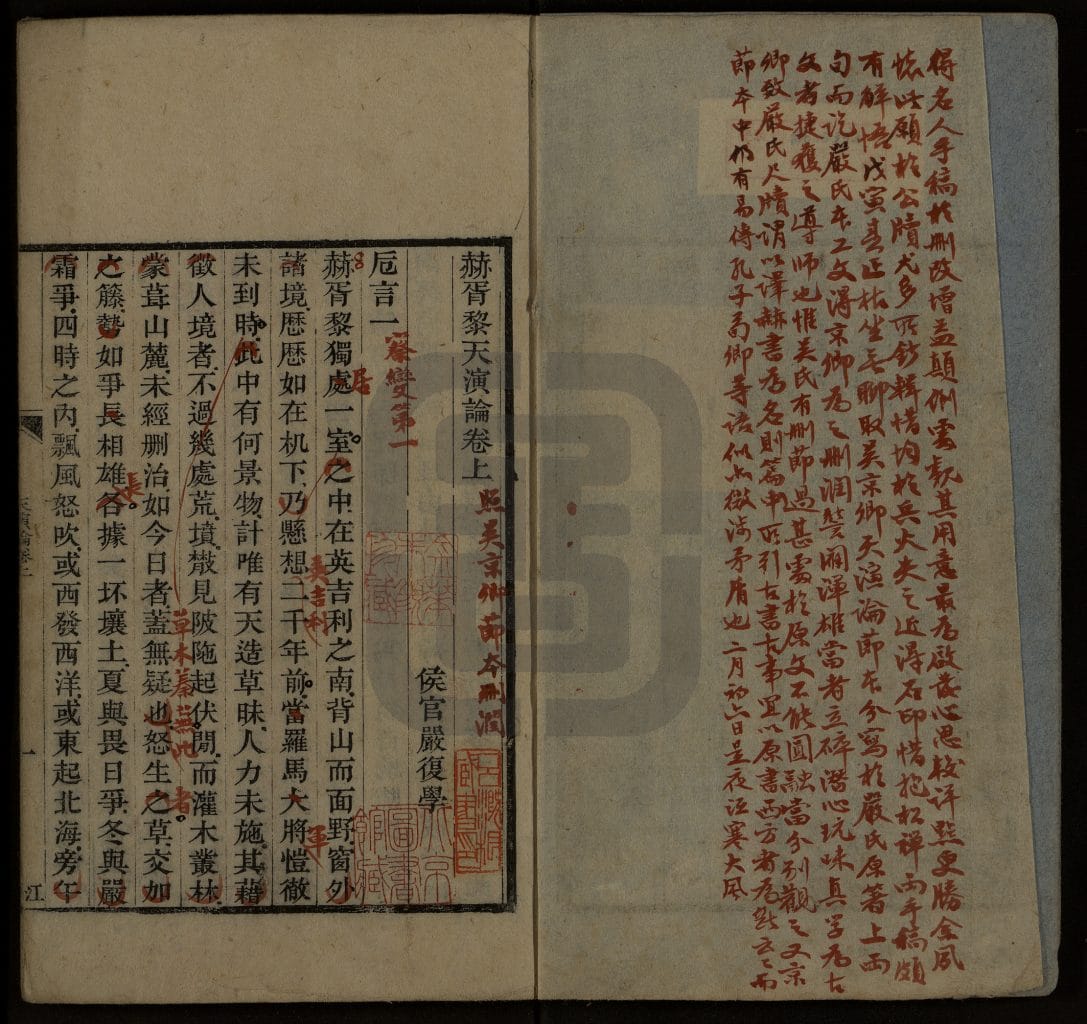

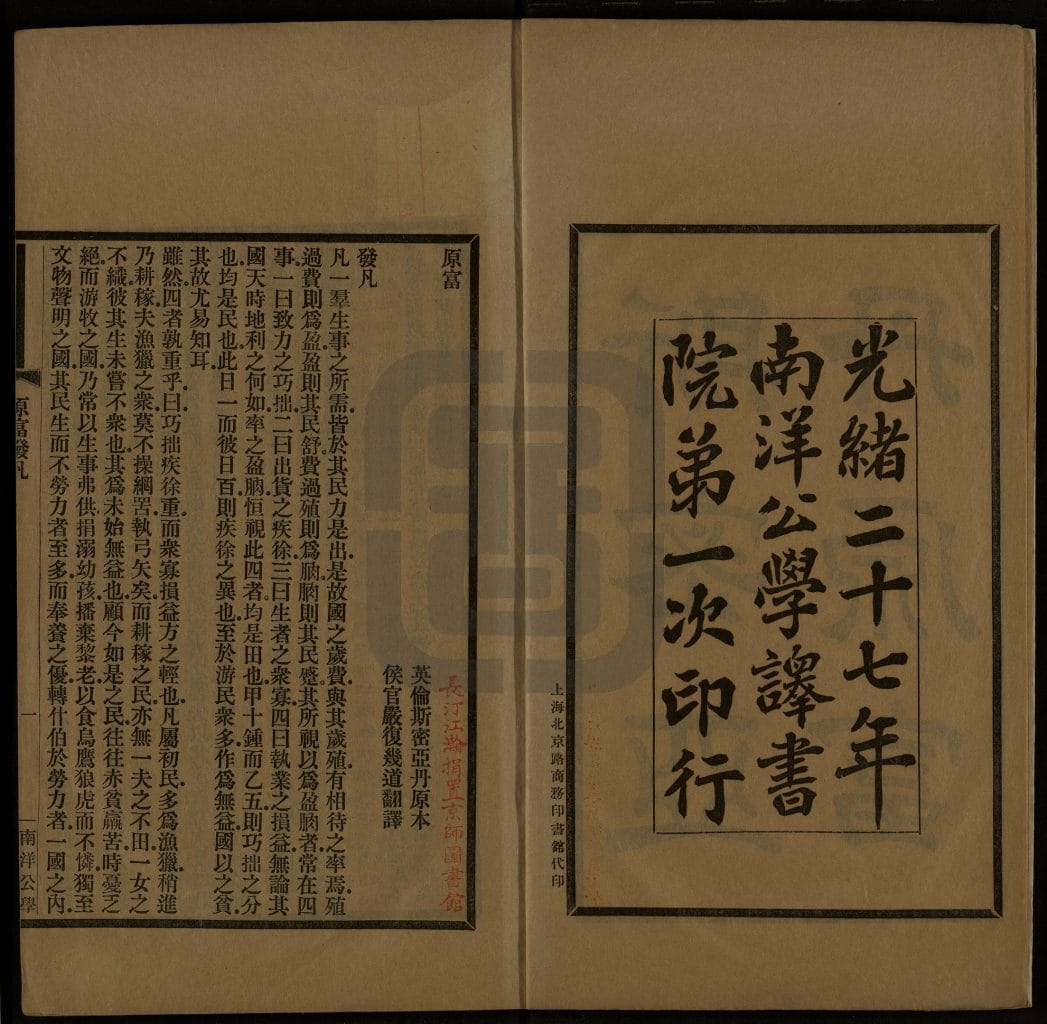

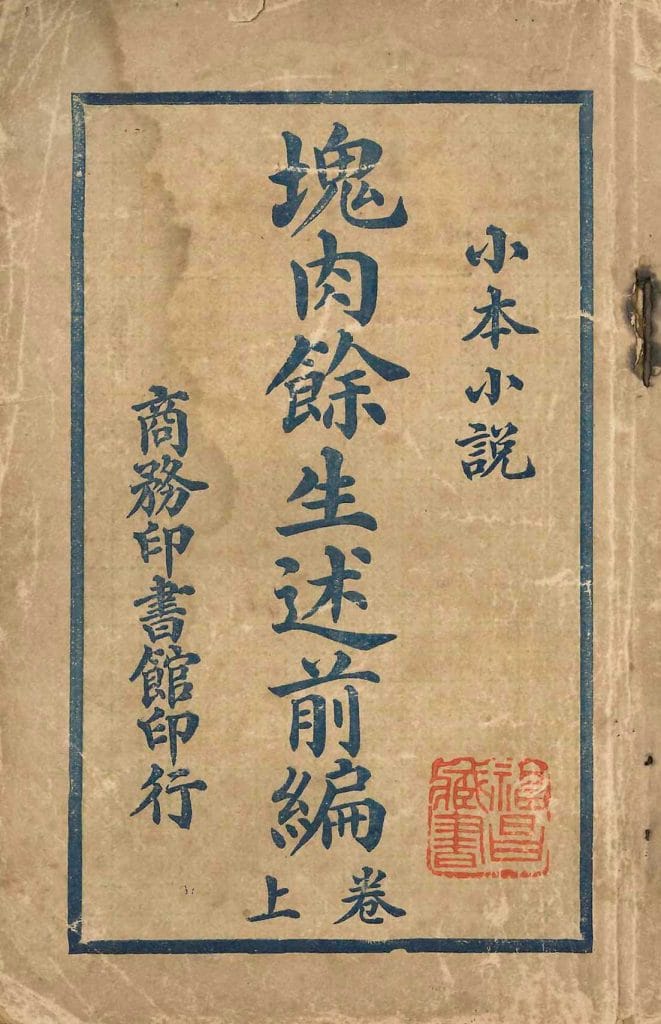

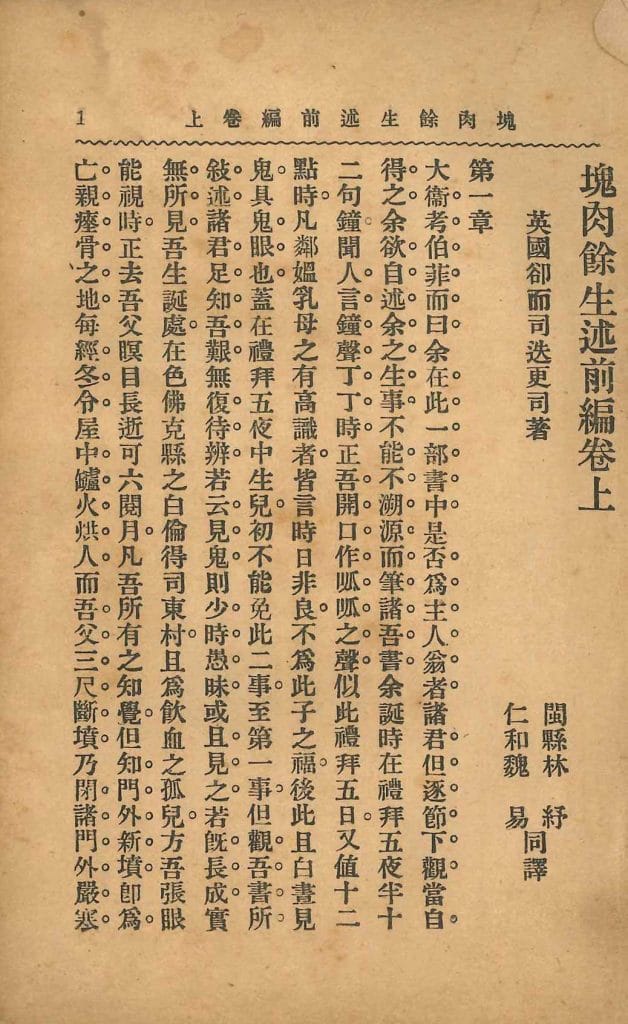

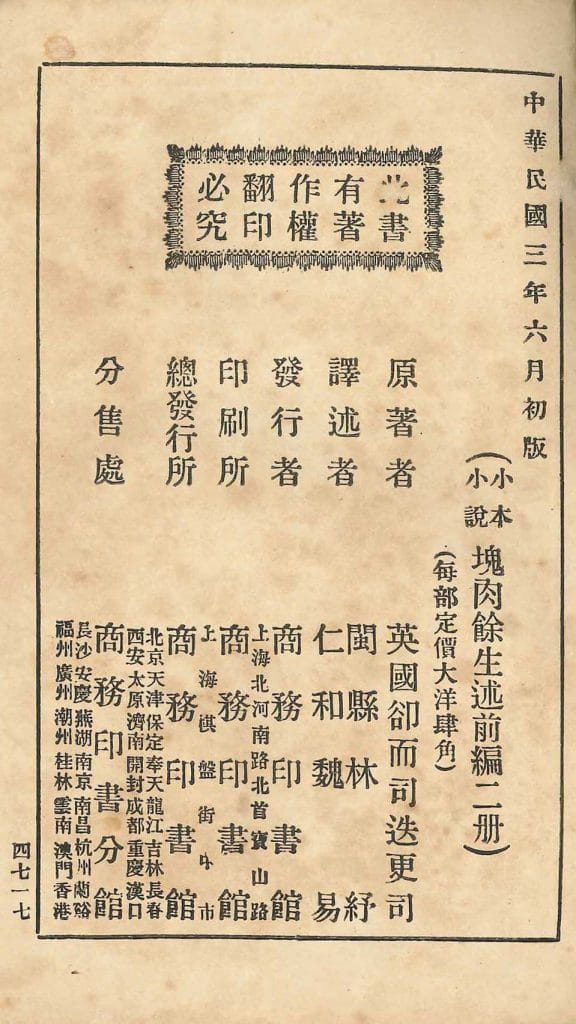

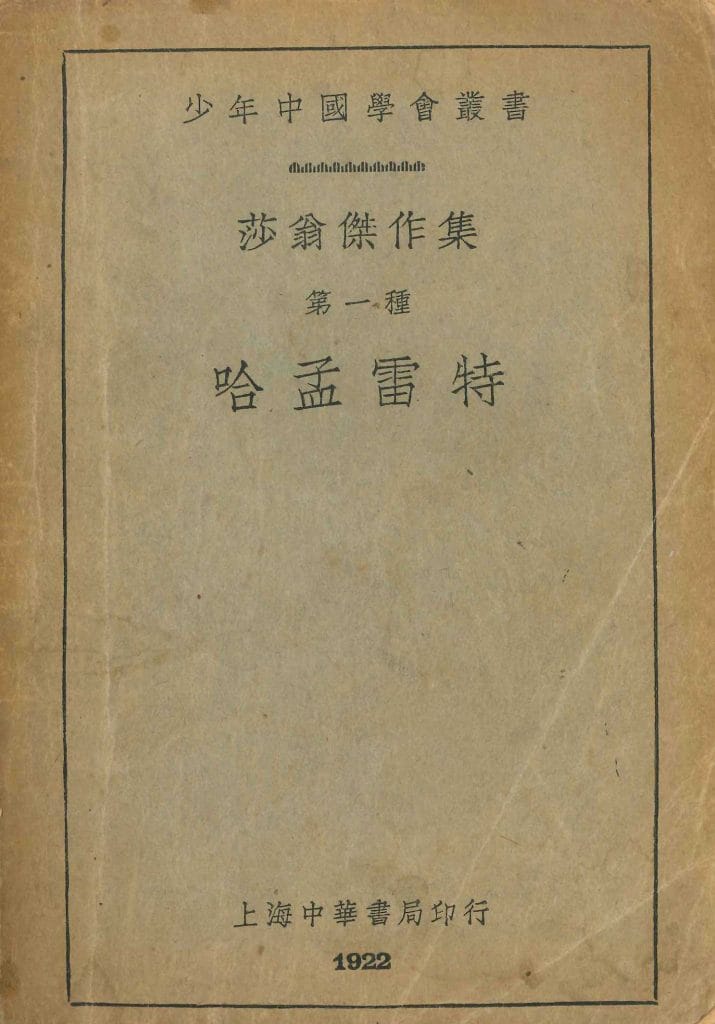

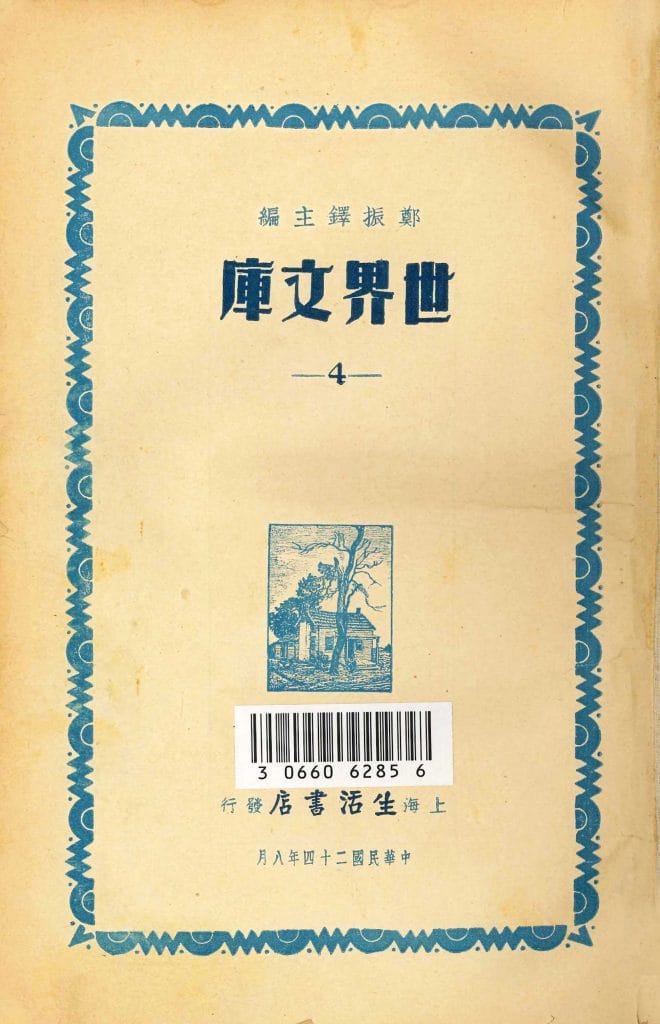

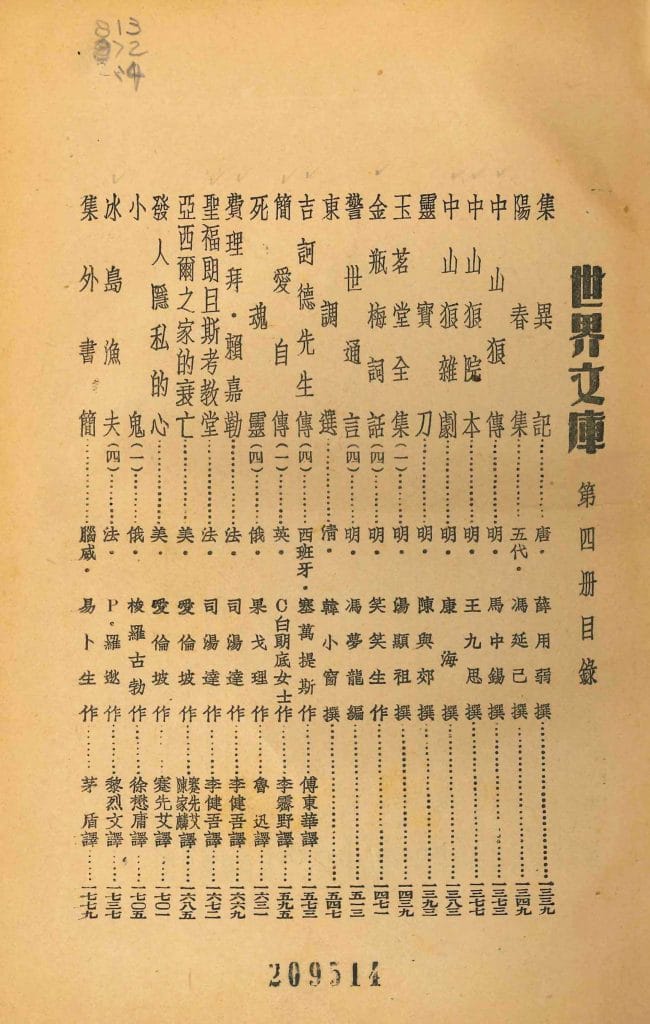

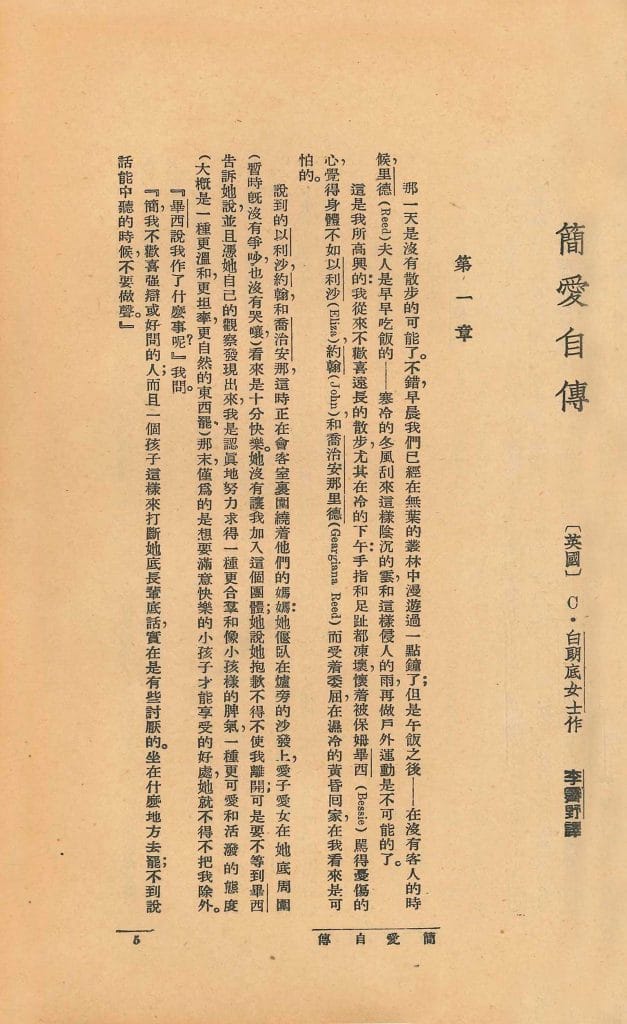

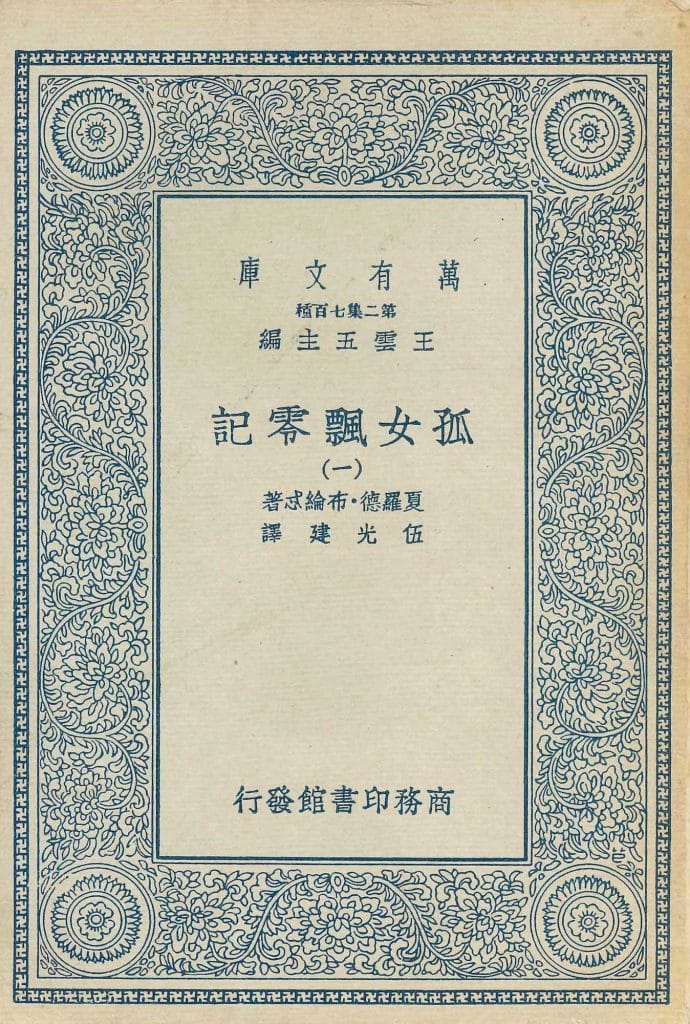

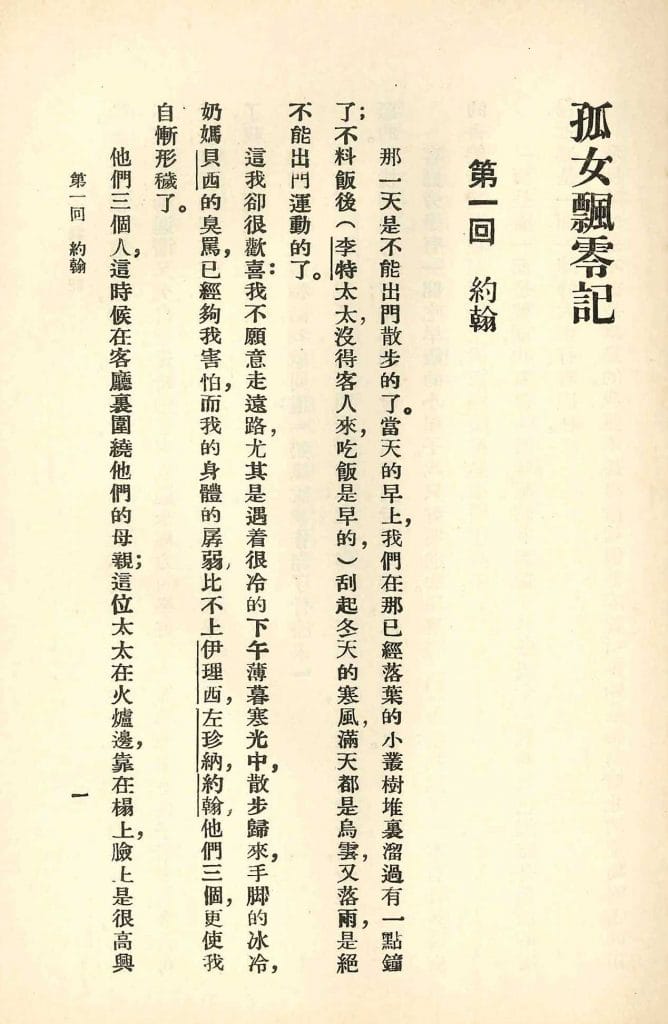

This Night and Morning translation was followed by many other firsts of English literature in China: the first introduction of Shakespeare by a Chinese in 1894 – by Yan Fu (严复 1854–1921), whose translations of Thomas Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics [天演论] and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations [原富] helped shape the development of modern Chinese history; the 1896 publication of Chinese renditions of four Conan Doyle (1859–1930) detective stories, the first of its kind in China; the first performance of a Shakespeare play in China, The Merchant of Venice, by the graduating class of St John’s University (Shanghai) in 1902; and the 1903 publication of an abridged translation of Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb. This latter work was followed by a full-text translation in 1904 rendered by Lin Shu (林纾 1852–1924); one of the most prolific translators of Western literature, his work includes Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe [撒克逊劫后英雄略] in 1905, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels [海外轩渠录] in 1906, and Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby [滑稽外史] and The Old Curiosity Shop [孝女耐儿传] in 1907 and David Copperfield [块肉馀生述] and Oliver Twist [贼史] in 1908. Somewhat extraordinarily, Lin Shu himself was monolingual and therefore had to rely on his language facilitators who had had the benefit of an education in Western countries. All of these works and many more – including translations of Beowulf, the works of Chaucer, Milton, Blake, Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Goldsmith, the Brontë sisters, the Brownings, George Eliot, Gaskell, Hardy, Stevenson, Wilde, Shaw, Conrad, Yeats, Joyce, Wells, Woolf, etc. – formed an important current in the literary and cultural life of China during the decades from the late 1800s to the early 20th century: indeed, this current is still flowing strongly in the 21st century.

English authors in China

In addition to textual translations (to translate literally means to ‘move from one place or condition to another’), English literature travelled to China in the form of visits made in person by important literary figures themselves. W Somerset Maugham (1874–1965), one of the most popular English authors of his day, came to visit in 1919 when the New Culture Movement in China was at a pivotal moment in its development. During his four-month visit, Maugham travelled 1,500 miles down the Yangtze River to get to know the land and its people, a journey which provided ample material for his play East of Suez (1922), travel book On a Chinese Screen (1922) and novel The Painted Veil (1925), which was later adapted into a Hollywood film. In 1929, I A Richards (1893–1979), author of Principles of Literary Criticism (1926) and Practical Criticism (1929), both seminal texts of the New Criticism, came to China to teach at Qinghua University and Peking University. He would go on to spend a total of five years in China, promoting an 850-word Basic English Programme to foster ‘better understanding between different cultures’. In 1932, Sir Harold Acton (1904–1994) introduced T S Eliot’s The Waste Land to the students of Peking University, and over the course of his seven-year stay in China he published two important co-translations, Modern Chinese Poetry (1936) and Famous Chinese Plays (1937). Then, in 1933, George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) paid a short visit and met with prominent cultural figures such as Lu Xun (鲁迅 1881–1936), Song Qingling (宋庆龄 1893–1981), Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培 1868–1940) and Lin Yutang (林语堂 1895–1976). Lu Xun was particularly impressed with the unrelenting social criticism rendered in Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, which had been mounted on a Shanghai stage back in 1920 – alas, without much success.

Experiencing English literature on English soil

The Chinese, on their part, also sailed halfway around the world to experience English literature and indeed English authors on native soil. As far back as in 1879, while serving as one of the earliest Chinese ambassadors in Europe, Zeng Jize (曾纪泽 1839–1890) went to see a performance of Hamlet in London; Zeng was impressed with the magnificence of Western theatres (‘more magnificent than a royal palace’) and how theatre was used to inspire patriotic feelings. Fast forward to a sunny July afternoon in 1925: Xu Zhimo (徐志摩 1897–1931), a young poet studying at King’s College, Cambridge, goes to visit Thomas Hardy at his Max Gate home in Dorchester, a pilgrimage of sorts to an ‘old hero’ he has admired as a towering luminary in the same galaxy as Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats. The two have a lively conversation and Hardy, to illustrate the points he was making (poems should be ‘organic’ and ‘living’) recites lines from Shakespeare (‘Tell me where is fancy bred, / Or in the heart or in the head?’), and Ben Jonson (‘Drink to me only with thine eyes, / And I will pledge with mine’). Buoyed up by this visit, Xu returned to China where he translated a dozen more of Hardy’s poems, thus becoming one of his foremost Chinese translators. When news of Hardy’s death came in January 1928, Xu Zhimo wrote a long article memorialising the passing of a literary hero, celebrating Hardy as a star forever shining in the sky and his achievements as transcending time, space and race. While in England, Xu Zhimo had also met and talked with Katherine Mansfield, Virginia Woolf and other English writers and scholars, meetings which had a palpable impact on the kind of new modern Chinese poetry he was writing.

Many other eminent Chinese writers and scholars benefited from experiencing and studying English literature on its native soil. Wu Mi (吴宓1894–1978), a student of 19th-century English literature, especially the Romantics, and a seminal figure in Chinese comparative literature, met with T S Eliot in 1930 and 1931 and discussed literature and literary criticism with him. Xiao Qian (萧乾 1910–1999), a prolific writer, war correspondent and accomplished translator of Shakespeare, formed a close friendship with E M Forster, author of A Passage to India and Aspects of the Novel, during his years studying at Cambridge University. Other well-known Chinese Cambridge alumni include Bian Zhilin (卞之琳 1910–2000), a poet, literary scholar and translator of Shakespeare, and Wang Zuoliang (王佐良 1916–1995), educator, author and editor of numerous books on English literature. The most famous Oxford alumnus is perhaps Qian Zhongshu (钱钟书 1910–1998), erudite scholar and author of Fortress Besieged (《围城》 1947) and many other voluminous books on arts and literature, whose undergraduate thesis was on the portrayal of Chinese in 17th- and 18th-century English literature.

The scandal of Lady Chatterley

The story of English literature in China is not all fairy tale and smooth sailing, though. D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) experienced a bumpy ride in its reception in China. This should not come as a surprise because the novel, with its ‘obscene’ language and frank treatment of sexual intimacy, had run into trouble with censors even in its home country, where the ban on open publication of an uncensored edition was not lifted until 1960 following a famous court case. When the novel first came to China in the 1930s, through several translations, it met with mostly positive reviews. Chinese writers such as Yu Dafu (郁达夫1896–1945) praised the novel for its honest treatment of sex as a wholesome expression of human nature, which, they believed, would have a liberating impact on Chinese readers long repressed by rather backward, unenlightened mores on such matters. The novel, unsurprisingly, was banned during the decades from 1949 to the late 1970s, during which time only a select few, who enjoyed high ‘security clearance’, could have access to the novel for ‘research’ purposes. The story of Lady Chatterley and her gamekeeper lover, however, did get leaked more widely during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) – in polymorphous, hand-copied forms, eagerly circulated among some sent-down youths [知青]. In 1986, editors at the Hunan People’s Press hit upon the idea of publishing a reprint of a 1930s translation of the novel to give the company a boost in the competitive book market. For days, trucks hummed outside the Press’s buildings waiting to load the freshly printed copies and carry them to eager bookstores. Any self-congratulatory euphoria the editors experienced didn’t last long. News of their success travelled to the censors in Beijing. Word came down fast. The book was banned. Copies already sold were recalled. Disciplinary punishments were doled out to those who had dared to let themselves go astray.

English literature in modern China

Fortunately, such dramas are now more an anomaly than regular occurrence. Indeed, ever since the establishment of the Tongwen Institute in Beijing (同文馆 precursor of Peking University) in 1862 English (both language and literature) has occupied an unparalleled place in education as well as literary and cultural life in China. Today, English literature, whether in translation or in the original (simplified, abridged or full-text), is taught and studied every day from middle school all the way to graduate programmes all across China. Plays by Shakespeare, Shaw and Wilde are performed perennially by professional artists in big cities and by student enthusiasts on university campuses. Even Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) has been adapted into a critically acclaimed play performed in the National Centre for the Performing Arts [国家大剧院] in Beijing and at other major theatres across the country, and sister Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) has been adapted into a ballet performed on the stages of Shanghai and London.

In the globalised world we live in today, one does not usually have to wait for months for the latest book from outside China to sail across seas and oceans to come ashore. However, the Chinese publishing industry was caught momentarily off guard when in the late 1990s the story of a young wizard at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry first took the world by storm; soon made aware of this new phenomenon, the industry caught up quickly and was able to put out Chinese translations of the first three books in the Harry Potter series in 2000. When the fourth book in the series was published in the same year, there was still a five-month period of ‘jet lag’, so to speak, before its Chinese translation reached the eager hands of tens of thousands of young readers (and their parents). From then on, though, Chinese ‘Potterheads’, young and old alike, could hold in their hands each of the new books in the series almost at the same time as their English and other Western brethren and sisters. It is a small world indeed, and cultural exchange such as that which has been outlined above certainly helps make it a richer and more interesting place for all to live in.

The text in the article is © Dr Shouhua Qi. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Shouhua Qi

Dr. Shouhua Qi is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the College of Liberal Arts, Yangzhou University and Professor of English at Western Connecticut State University. Among Qi’s most recent publications are The Bronte Sisters in Other Wor(l)ds (coeditor and contributing author, 2014) and Western Literature in China and the Translation of a Nation (2012), both published by Palgrave MacMillan. Qi is working on a book titled Adapting Western Classics for the Chinese Stage (to be published by Routledge in 2018).