Mrs Dalloway and the First World War

Mrs Dalloway, which takes place on one day in June 1923, shows how the First World War continued to affect those who had lived through it, five years after it ended. David Bradshaw explores the novel’s commemoration of the dead and evocations of trauma and mourning.

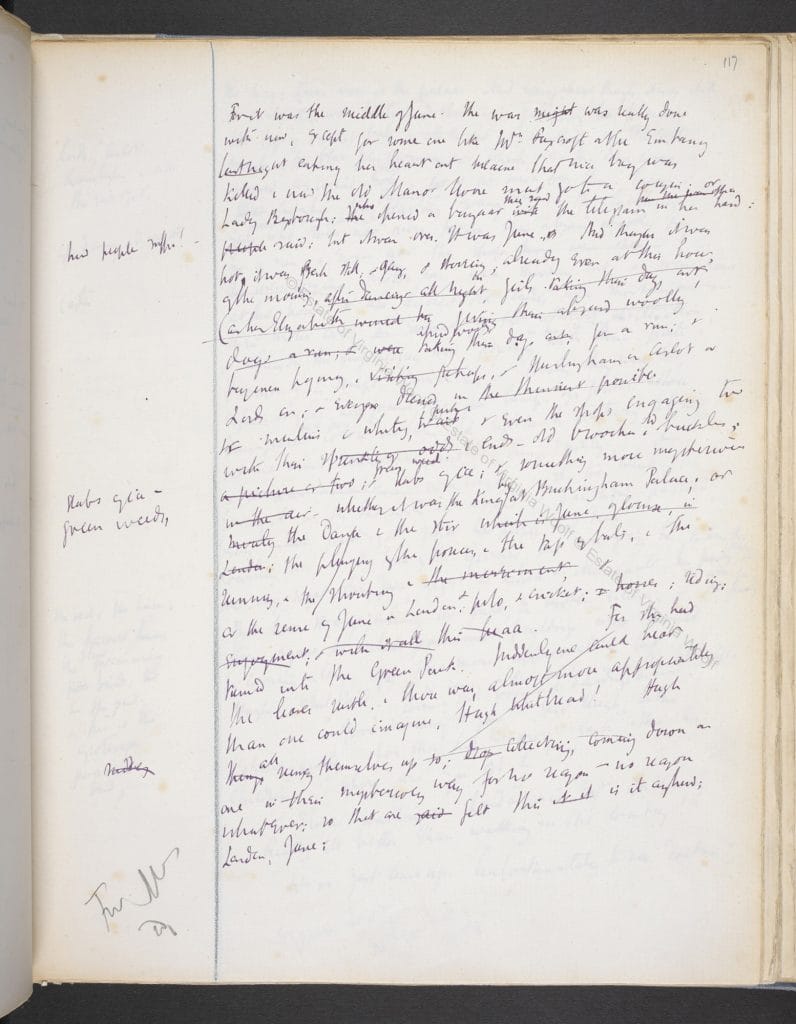

Set in June 1923, the First World War (1914–18) still hangs heavy in Mrs Dalloway’s hot London air, reinforcing how for Virginia Woolf and her fellow Britons the trauma of the conflict was ongoing, its unprecedented devastation still raw and ineradicable for the relatives, friends and loved ones of the unreturned. Time and again, the novel reveals how the myriad anxieties and overwhelming grief of the war were etched into every aspect of post-war life. In its opening pages, for example, we read that an aeroplane hovering over London creates unease in those beneath it because, even on such a balmy summer day five years after the conclusion of hostilities, the sound of the plane can still ‘ominously’ bring to mind the German planes that had attacked the capital so terrifyingly during the war.[1] Equally, a glimpse of Mrs Foxcroft ‘at the Embassy last night still eating her heart out because that nice boy was killed’ (p. 4) in the war, and our knowledge that Miss Kilman was dismissed from her teaching post during the conflict because of her German-sounding surname, only enrich our sense of Mrs Dalloway’s status as, among other things, a war novel of towering importance: ‘This late age of the world’s experience had bred in them all, all men and women, a well of tears’ (p. 8); ‘in all the hat shops and tailors’ shops strangers looked at each other and thought of the dead’. As the mysterious grey car glides through St. James’s, it passes, among other onlookers, ‘orphans, widows, the War’ (p. 17).

Falling leaves and national commemoration

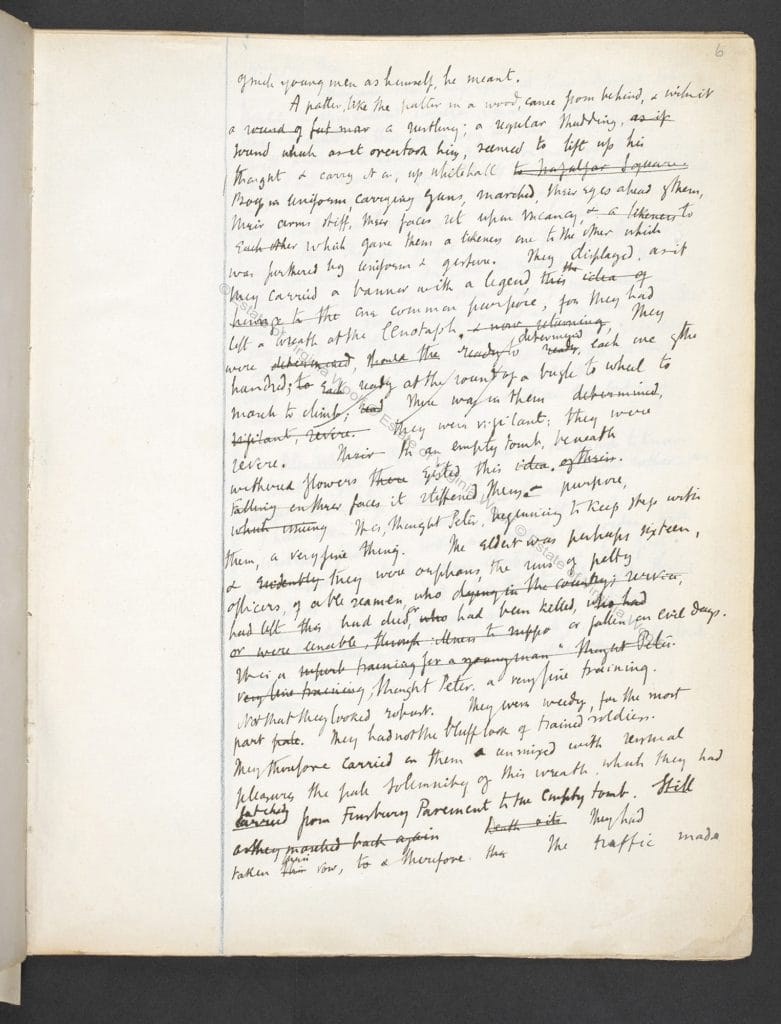

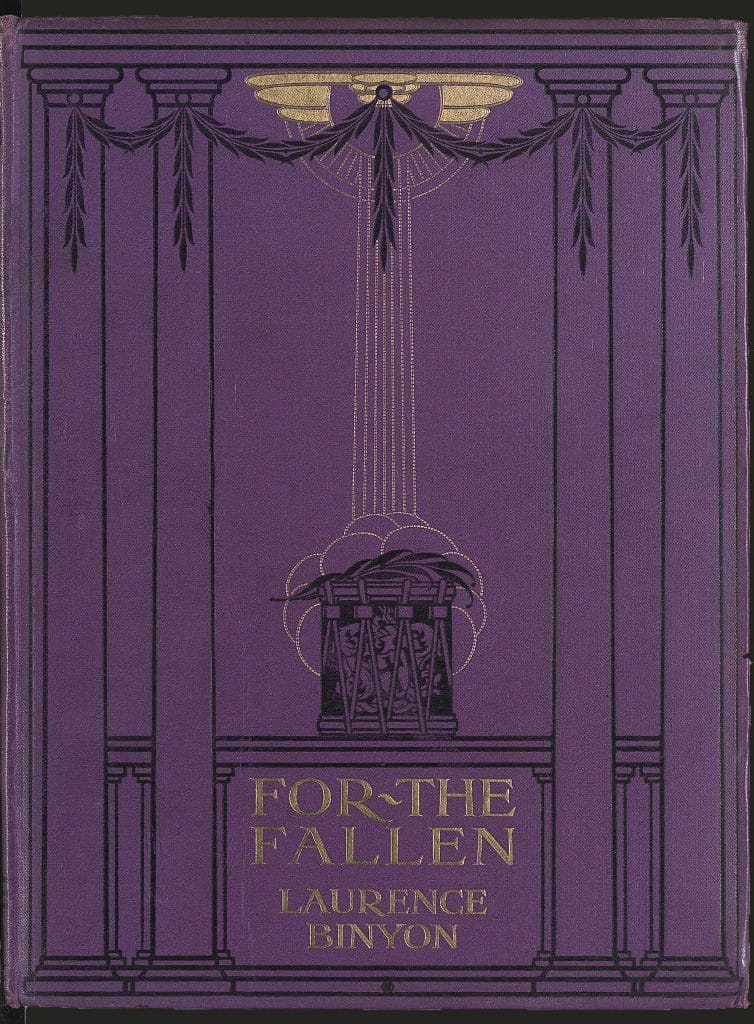

While it is obvious, however, that Mrs Dalloway is an eloquent condemnation of militarism and war, Woolf’s fourth novel is also a commemorative text which memorialises the war dead. In fact, at one point or another, every element of the post-war culture of remembrance is evoked or brought into focus in the novel and, on each occasion, the official sites and rituals of national mourning are treated with something akin to straightforward veneration, rather than satire or hostility, as if Woolf, too, is acknowledging, in Hugh Whitbread’s words, ‘what we owe to the dead’ (p. 93). Indeed, there are moments of silent observance in the text which are almost ceremonial in their reverence and dignity. So while the war dead throng the text and a victim of shell shock is one of its central characters, more subtly, but just as scrupulously, the novel also commemorates ‘the fallen’ (p. 76) in ways which seem either to bring to mind or parallel the various rituals of remembrance which the government had instituted after the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. This is made absolutely clear in the way the boy soldiers, who have just laid a wreath at the Cenotaph, enter Peter Walsh’s consciousness as he walks up Whitehall:

A patter like the patter of leaves in a wood came from behind, and with it a rustling, regular thudding sound, which as it overtook him drummed his thoughts, strict in step, up Whitehall … Boys in uniform, carrying guns, marched with their eyes ahead of them … (p. 4)

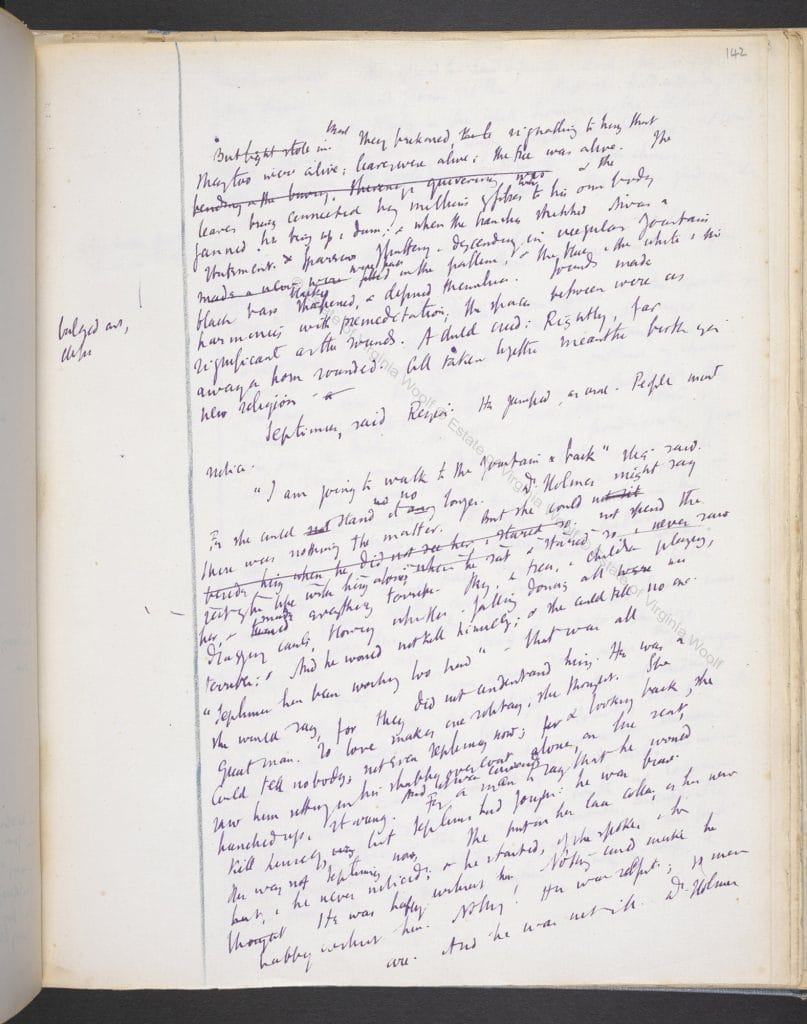

The arrestingly autumnal phrase with which this quotation begins attracts the reader’s eye not least because we know that Mrs Dalloway is set on an unusually hot summer’s day. Once we recall, however, that falling or fallen leaves are an ancient literary symbol for the dead, Woolf’s intention becomes clear. In effect, the marching boy soldiers are accompanied by a march past of the war dead whose ranks they are being drilled to fill. In exploiting the fallen leaves topos, then, Woolf not only problematises the boy soldiers’ presence in Whitehall by presaging their deaths in battle, but also, like Walsh, augments their act of remembrance at the Cenotaph. This same topos is deployed a little further on when the crooning ‘battered woman’ opposite Regent’s Park tube station is likened to ‘a wind-beaten tree for ever barren of leaves which lets the wind run up and down its branches singing …’ The old woman laments lost love at both a personal level and in terms of the nation’s collective sense of loss in the early 1920s, after ‘death’s enormous sickle had swept those tremendous hills’ (p. 69). Significantly, as Walsh gives the woman a coin, ‘the passing generations … vanished, like leaves, to be trodden under, to be soaked and steeped and made mould of …’ (p. 70). Similarly, the fallen leaves imagery probably helps to explain why, sitting in Regent’s Park, the grief-stricken Septimus Warren Smith becomes ever more convinced that ‘leaves were alive, trees were alive … the leaves being connected by millions of fibres with his own body’ (p. 19), and it also clarifies, no doubt, why he believes ‘Men must not cut down trees’, and why the sparrows of central London sing to him ‘in voices prolonged and piercing in Greek words, from trees in the meadow of life beyond a river where the dead walk, how there is no death’ (p. 21). There is even ‘a curious pattern like a tree’ (p. 13) on the blinds of the sumptuous grey car that travels down Bond Street on its way to Buckingham Palace.[2]

Miss Kilman makes a poignant visit to the ‘tomb of the Unknown Warrior’ (p. 113) in Westminster Abbey (her brother has been killed in the war), but the most significant act of observance in the whole novel occurs as the sky-writing aeroplane circles overhead:

All down the Mall people were standing and looking up into the sky. As they looked the whole world became perfectly silent, and a flight of gulls crossed the sky, first one gull leading, then another, and in this extraordinary silence and peace, in this pallor, in this purity, bells struck eleven times, the sound fading up there among the gulls. (p. 18)

Mrs Dalloway’s 11 a.m. silence is surely the fictional counterpart of the annual 11 a.m. Silence, first observed in November 1919, which by 1925, when the novel was first published, had become a key feature of the Remembrance Sunday ceremony. In the mind of Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, the man who came up with the idea of the Silence, its emphasis was not on collective mourning, but on social integration, ‘to remind us of the greater things we hold in common’,[3] and this is also Woolf’s purpose at this point in a novel which is more generally concerned with exposing divisions, exclusions and inequalities. A little further on, the novel’s 11 o’clock silence is reprised when Big Ben strikes the half hour and Walsh looks back to his meeting with Clarissa 30 minutes earlier:

As a cloud crosses the sun, silence falls on London; and falls on the mind. Effort ceases. Time flaps on the mast. There we stop; there we stand. Rigid, the skeleton of habit alone upholds the human frame. Where there is nothing, Peter Walsh said to himself; feeling hollowed out, utterly empty within. (p. 42)

As with so many words, phrases and descriptive passages in Mrs Dalloway, this excerpt, which recalls both the official Silence and the Cenotaph (‘hollowed out, utterly empty within’; the word cenotaph means ‘empty tomb’), lends itself to a commemorative interpretation.

Monuments

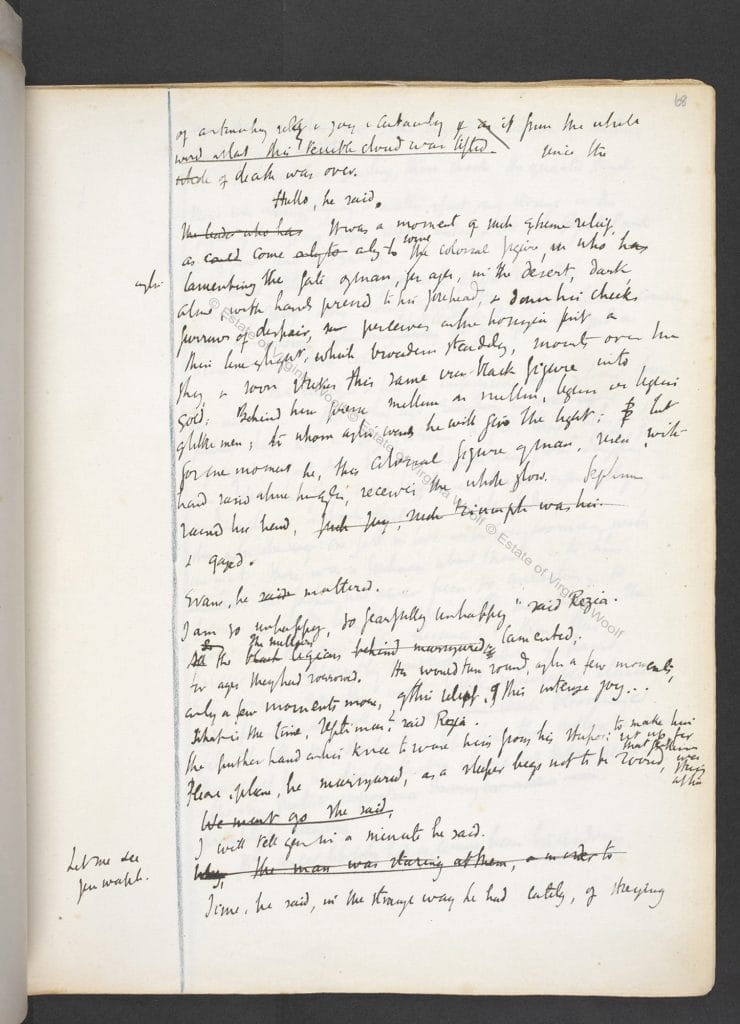

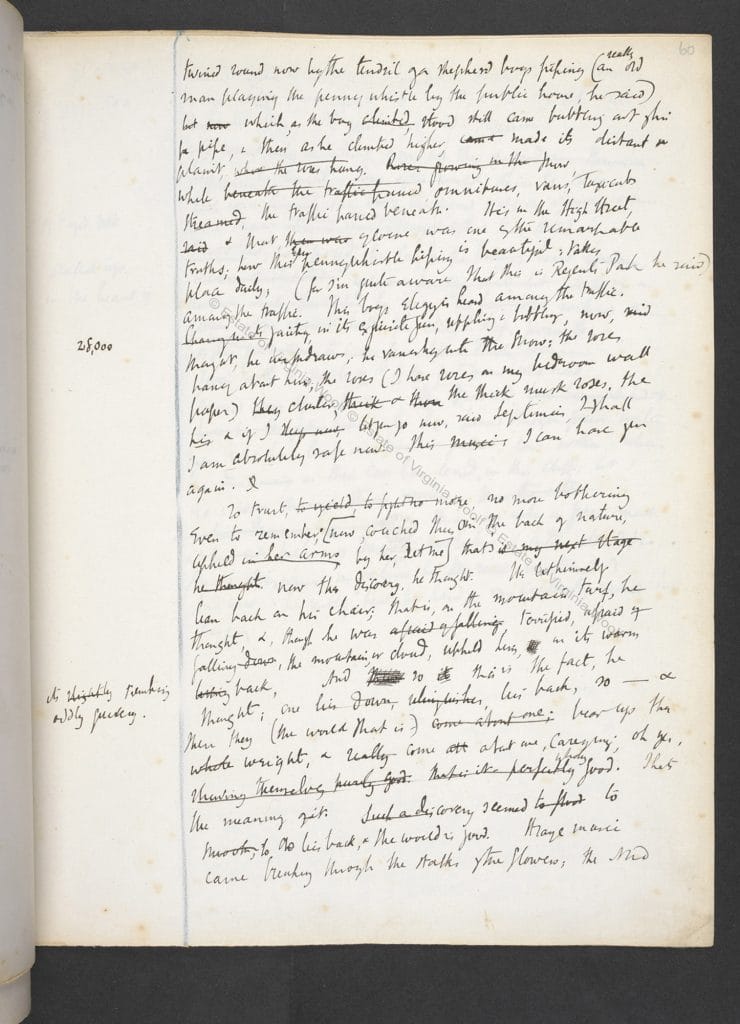

The novel also makes its own contributions to the proliferation of war memorials, military statuary and commemorative monuments that sprang up in the 1920s across the United Kingdom. For example, the description of the ‘giant figure’ (p. 48) of the grey nurse in Regent’s Park is noteworthy – is this a ghostly allusion to Edith Cavell, the nurse executed by the Germans in October 1915 for helping to save the lives of Allied soldiers? She morphs, in Peter Walsh’s Regent’s Park dream, into the equally symbolic figure of an ‘elderly woman who seems … to seek … a lost son; to search for a rider destroyed; to be the figure of the mother whose sons have been killed in the battles of the world’ (p. 49). Likewise, as a spectral Evans approaches Septimus in Regent’s Park, ‘with legions of men prostrate behind him’ (p. 60), Septimus raises his hand ‘like some colossal figure’ (p. 59). Doris Kilman also assumes a statue-like monumentality at one point in the novel. Waiting for Elizabeth Dalloway as they prepare to go to the Army and Navy Stores for tea, Miss Kilman is described as standing ‘with the power and taciturnity of some prehistoric monster armoured for primeval warfare’ (p. 106), while, on her way home from the Strand, the heat gives Elizabeth Dalloway’s ‘cheeks the pallor of white painted wood; and her fine eyes, having no eyes to meet, gazed ahead, blank, bright, with the staring, incredible innocence of sculpture’ (p. 115). Peter Walsh thinks that ‘old Miss Parry … would always stand up on the horizon, stone-white, eminent, like a lighthouse’ (p. 138), whereas Clarissa, on the other hand, is a pale and depleted semi-invalid who spends her solitary nights in a narrow bed with tight white sheets restricting her movement – almost as if she has been trussed up like a battlefield casualty. Clarissa is almost certainly a victim of the influenza pandemic of 1918–20, but she is also to be one of the novel’s lingering wraiths: ‘Since her illness she had turned almost white’ (p. 31). Even so, her meeting with Peter Walsh has a suppressed air of violence about it – Peter fingering his penknife and Clarissa armed with her scissors.

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto

Septimus and Evans, who ‘was killed, just before the Armistice, in Italy’ (p. 73), were almost certainly blown up during the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which took place in the mountains of northern Italy and which concluded as late as 4 November 1918 (the Armistice was declared on 11 November). The tragedy of Evans’s death and Septimus’s torment, therefore, is only heightened by the reader’s awareness that this battle was almost wholly pointless, with the outcome of the war already decided. The mountainous location of this futile engagement also helps to explain why, ‘alone with the sideboard and the bananas’ in his Bloomsbury accommodation, Septimus reflects that he is ‘not on a hill-top; not on a crag; [but] on Mrs Filmer’s sitting-room sofa … Where he had once seen mountains … there was a screen’ (p. 123). And we can also see that when Clarissa asks herself, just after thinking her party will be a failure, ‘Why seek pinnacles and stand drenched in fire?’ (p. 142), her peculiar turn of phrase is drawn directly from the craggy warfare of the Italian Front, and is another of the numerous thoughts and experiences she shares with Septimus.[4] And an appreciation of the whereabouts of Evans’s death also enriches Rezia’s recollection of ‘a flag slowly rippling out from a mast when she stayed with her aunt at Venice. Men killed in battle were thus saluted …’ (p. 127).

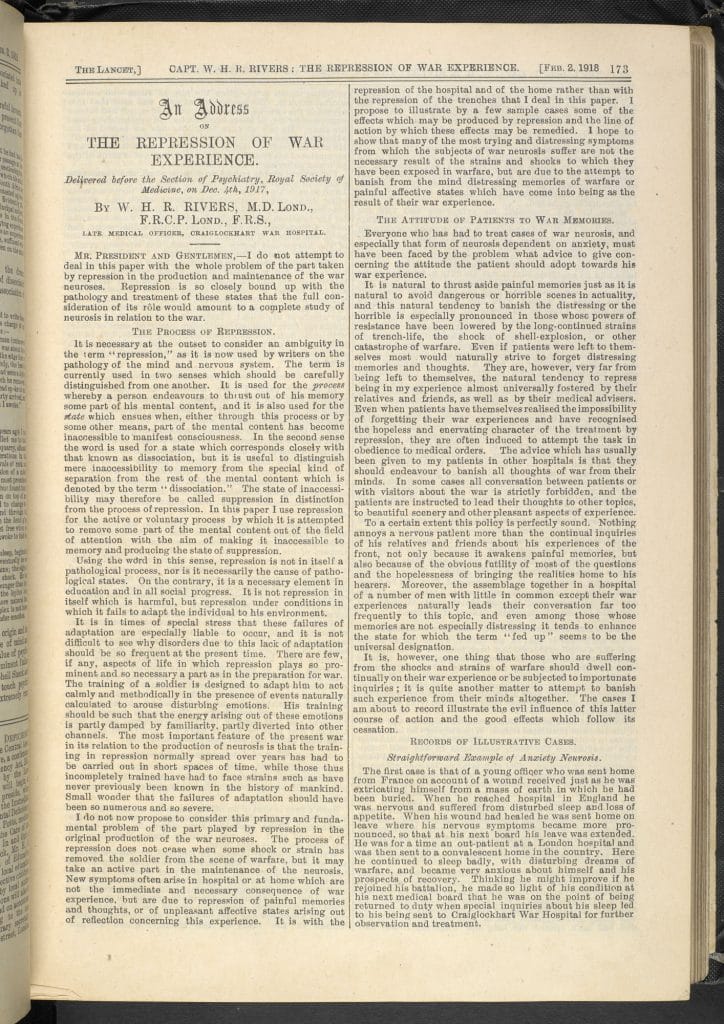

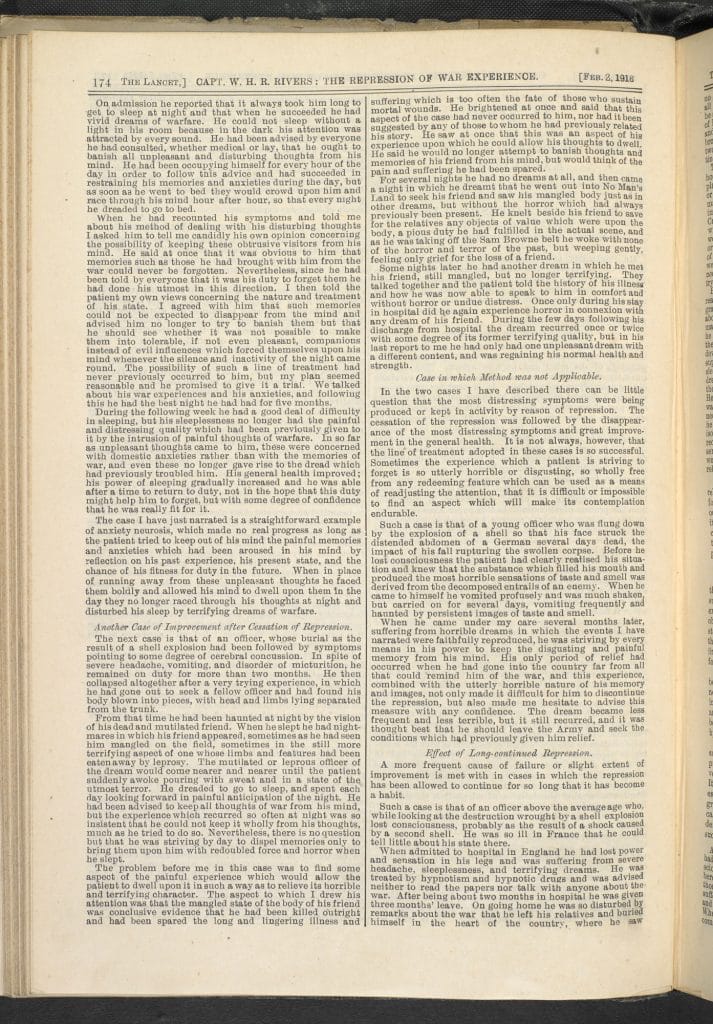

But is Septimus’s distress wholly attributable to the trauma of his experience of war? Possibly, but it is more than likely that he is also crippled with grief and guilt (homosexuality was only decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967) about his powerful, homoerotic feelings for Evans, sentiments which saturate his tortured mind in 1923. Moreover, the recurrence of Greek allusions and references, like the sparrows singing in Greek quoted above, in the passages in which Evans and Septimus are in focus, offer further evidence that Woolf wished to represent their relationship as having a homoerotic charge reminiscent of that between the young Clarissa and Sally Seton (pp. 27–30).[5] So although Septimus’s anguished repression is most obviously a symptom of what the eminent neurologist and psychiatrist W H R Rivers called ‘The Repression of War Experience’, and what became more generally known as ‘shell shock’, it is also a harrowing legacy of his intimacy with Evans.

Spectres of war

Finally, we should take note of how so many of the descriptions of day-to-day life in the novel are couched in military language or language that could be readily applied to military exploits. For example, the verb ‘plunge’ on the first page of the novel (see also p. 32, where Clarissa is observed ‘plunging’ her hand into her wardrobe) is a word that is often collocated with the wielding of a bayonet or knife, but here it is used to describe an act of defenestration that anticipates Septimus’s suicidal plunge. Similarly, on page 10, we read that Miss Kilman’s soul is ‘rusted with that grievance sticking in it, her dismissal from school during the War’, as if her sense of injustice were a lump of battlefield shrapnel, while for Clarissa, Doris Kilman is ‘one of those spectres with which one battles in the night’ (p. 10). Elsewhere we read that in the West End of London ‘the spirit of religion was abroad with her eyes bandaged tight and her lips gaping wide’ (p. 12), as if it has been gassed. Richard Dalloway returns to Clarissa from the lunch-party of Lady Bruton (‘a spectral grenadier’ (p. 152)) ‘[b]earing his flowers like a weapon’ (p. 99) and thinking of ‘the war, and thousands of poor chaps, with all their lives before them, shovelled together, already half forgotten’ (p. 98), leaving his hostess to dream of ‘commanding battalions marching to Canada’ (p.95), while in the Army and Navy Stores, Elizabeth guides Miss Kilman ‘as if she had been a great child, an unwieldy battleship’ (p. 110). As Elizabeth travels home on her bus, the wind blows ‘a thin black veil over the sun and over the Strand’ (p.117) like a vast funeral pall. A little further on, Peter Walsh thinks of London thrusting her ‘bayonets’ (p. 137), i.e. electric street lights, ‘into the sky’, just as earlier in the novel Lucy, Clarissa’s maid, handles her parasol ‘like a sacred weapon’ (p. 25).

Jacob’s Room (1922) and To the Lighthouse (1927), the two novels that book-end Mrs Dalloway, are also, to a certain extent, war novels, but neither is so steeped in the conflict and its grief-stricken aftermath as the novel they enfold. Indeed, as a fictional account of the impact of the First World War on British society – and the way ‘military music’ (p. 117) still resounds within London’s streets and messages continue to be transmitted from ‘the Fleet to the Admiralty’ (p. 6) – it is unmatched.

脚注

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, ed. by David Bradshaw (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2000), p. 17. All subsequent page references are to this edition.

- For more on this aspect of the novel, see David Bradshaw, ‘“Vanished, Like Leaves”: The Military, Elegy and Italy in Mrs Dalloway’, Woolf Studies Annual, 8 (2002), pp. 107–25.

- Quoted in Adrian Gregory, The Silence of Memory: Armistice Day 1919–1946 (Oxford and Providence, Rhode Island: Berg, 1994), p. 9.

- See Mrs Dalloway, pp. xxxiv–xlii.

- See Mrs Dalloway, pp. xxxv–xxxviii.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: David Bradshaw

David Bradshaw (1955–2016) was Professor of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of Worcester College. Specialising in late 19th and early 20th century literature, he published on Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, T S Eliot, E M Forster, Aldous Huxley, and Evelyn Waugh, with a particular interest in areas including censorship and obscenity, political and social movements, and the city. Among other modernist texts he has edited Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse and The Waves, co-edited Prudes on the Prowl: Fiction and Obscenity in England, 1850 to the Present Day, and was Co-Investigator of the Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh project at University of Leicester.