Jane Eyre and the 19th century woman

Professor Sally Shuttleworth explores how Charlotte Brontë challenges 19th-century conceptions of appropriate female behaviour through the creation of a heroine who works, demands respect and combines self-control with passion and rebellion.

Professor John Bowen explores the central role of women in Jane Eyre and the unique role of the governess in 19th-century society. Filmed at the Brontë Parsonage, Haworth.

Femininity and rebellion

When Jane Eyre (1847) was published by Charlotte Brontë under the masculine pseudonym Currer Bell, it was received with great acclaim by some critics, and harsh criticism by others. The conservative Lady Eastlake suggested that if the book was by a woman ‘she had long forfeited the society of her own sex’. In addition to this lack of femininity, she also diagnosed a spirit of rebellion which she likened to the working class uprisings of the Chartists, with their demands for votes for the working people, and also the political revolutions which were then sweeping across Europe.[1] Jane Eyre unsettled views as to how women should act and behave, suggesting, in Lady Eastlake’s eyes, almost an overthrowing of social order. Unlike the long-suffering heroines in Charlotte Brontë’s early writings, who pine away for the dashing, promiscuous Duke of Zamorna, Jane demands equality and respect. ‘Do you think’, she demands of Rochester, ‘I am an automaton? – a machine without feelings?’. She speaks to him as one spirit to another, ‘equal – as we are’ (ch. 23). One can find, however, elements of this rebelliousness in the early writings, which cover a period of Brontë’s life from early adolescence to her late 20s. In ‘Visits in Verreopolis’ (1830), the noble Zenobia, who is deeply learned in the classics, is subject to ridicule by various males. The Duke of Wellington suggests that women are like swans, graceful in the water, but when they presume to leave their natural element, the home, they have an ‘unseemly waddle’ which entitles everyone ‘to laugh till their sides split at the spectacle’.[2] Interestingly, Zenobia is also prone to fits of rage or madness, and is described as having a West Indian, or Martinique complexion, which makes her also a forerunner of the ‘mad wife’.

Women should be allowed to use their talents

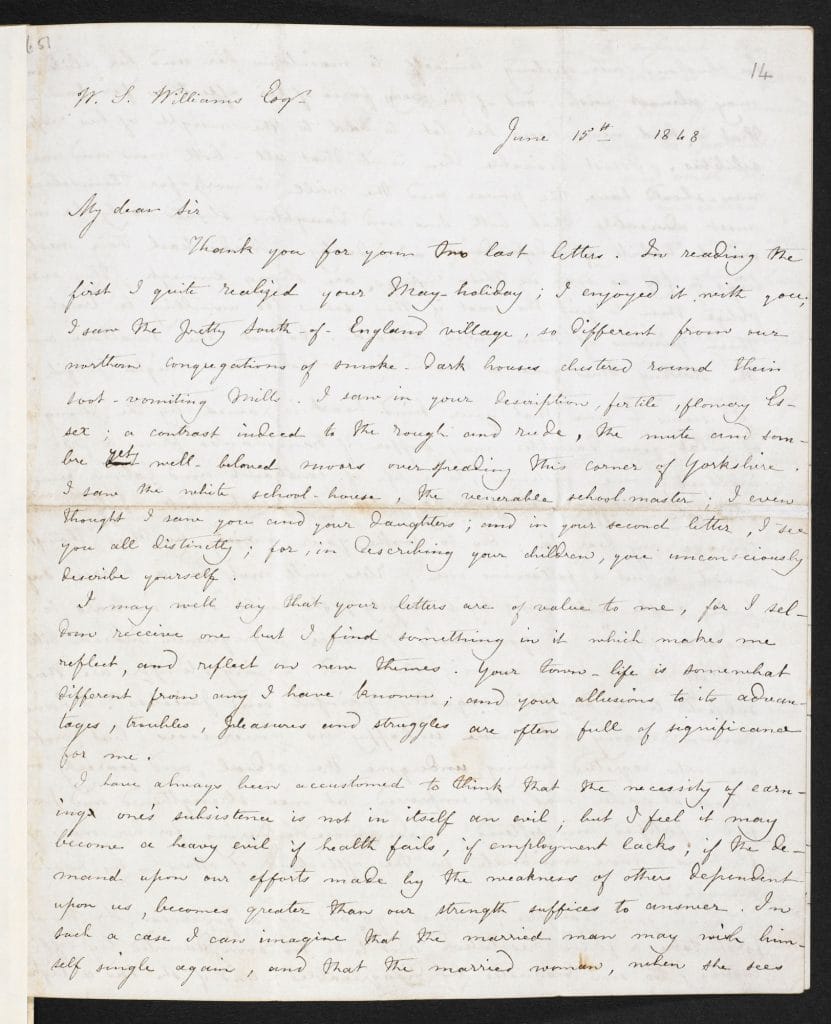

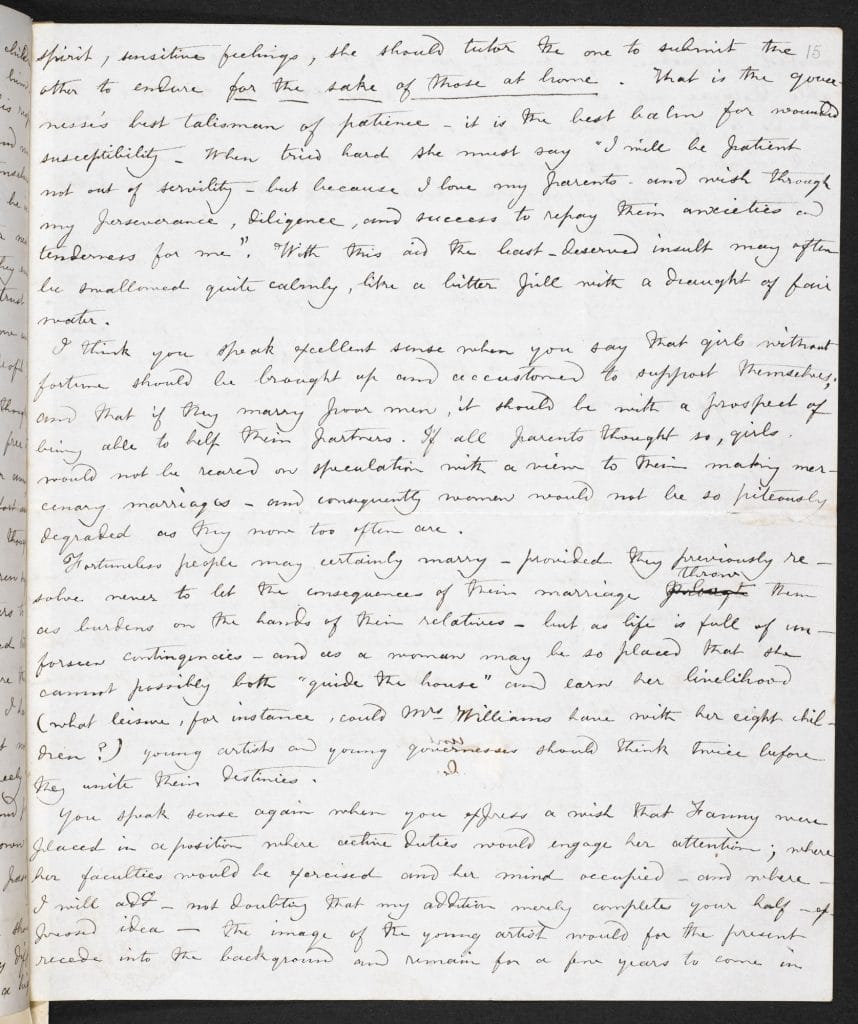

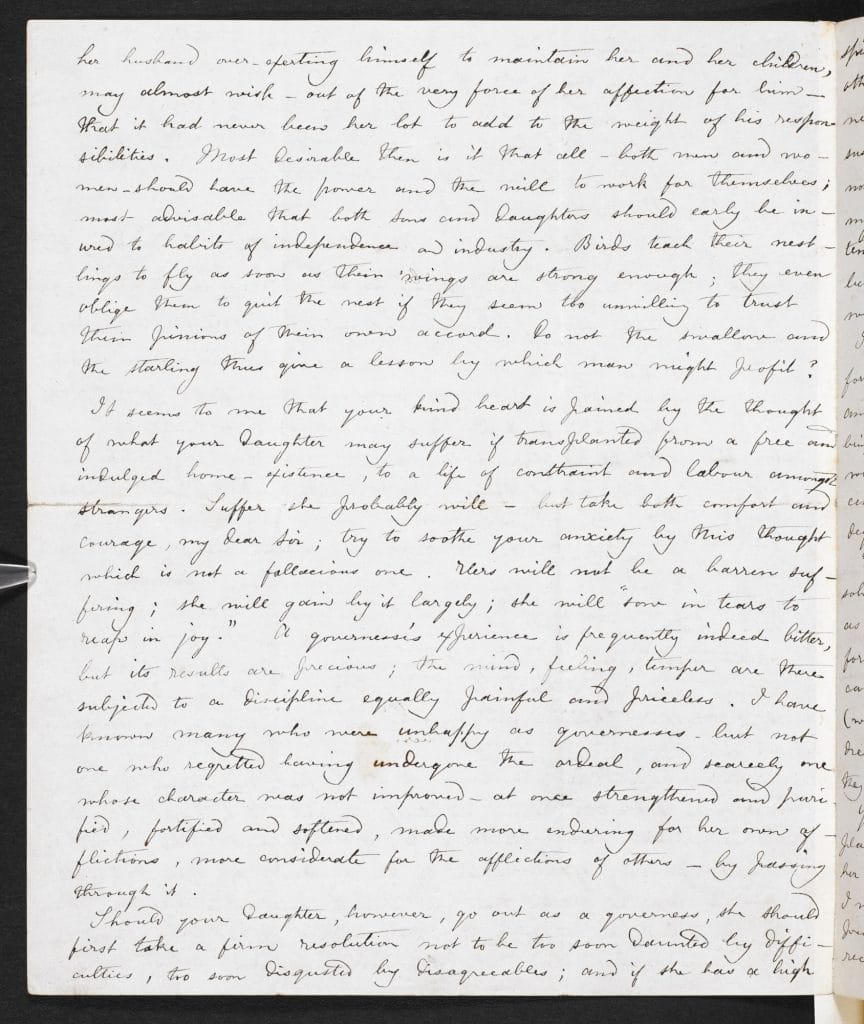

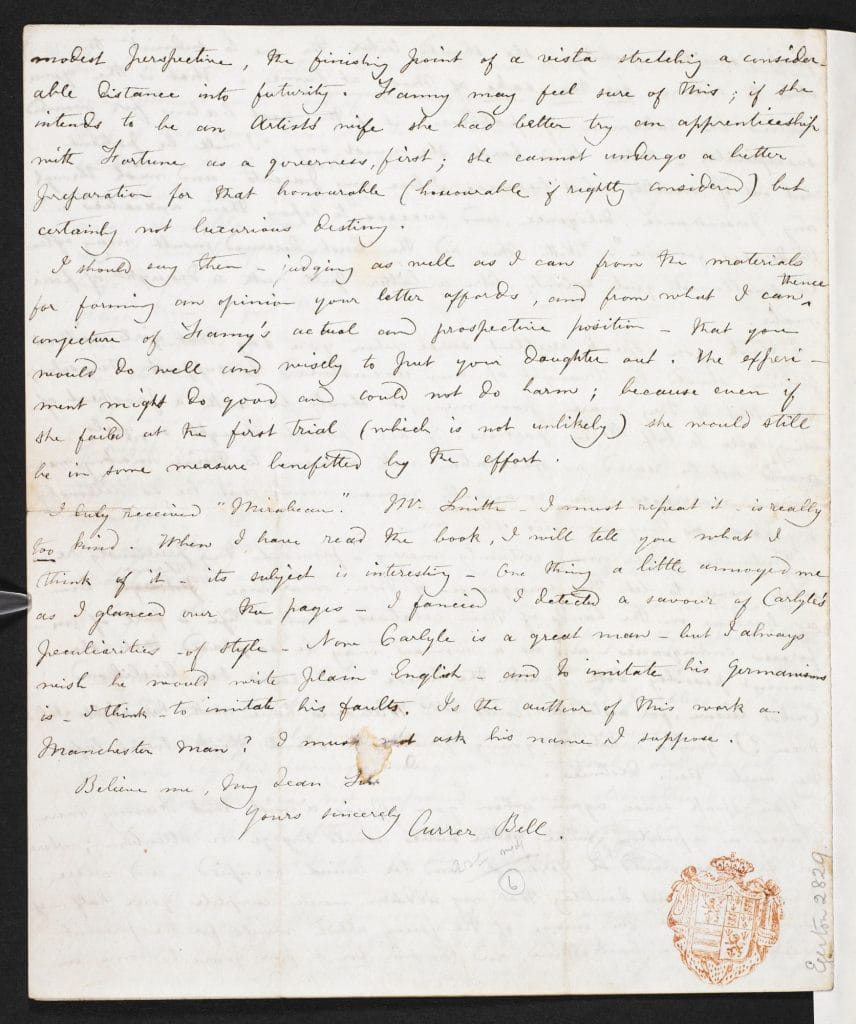

Despite the spirit of rebelliousness which flows through Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë was not overtly radical in her social views. On reading an article in the Westminster Review (1851), which argued for women’s rights to vote and to work, she writes to the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell that while she approves of many of the writer’s arguments she feels they are lacking in ‘heart’ and tender feelings.[3] While Brontë does not approve of women voting, she does believe they should be allowed to work. In the novel, Jane makes a passionate plea for women to be allowed to use their talents, and not to be confined to the home ‘making puddings and knitting stocking, …playing on the piano and embroidering bags’ (ch. 12). Charlotte Brontë herself had worked as a governess and a teacher, but had hated it. Her views come over clearly in a letter to her brother Branwell, written while she was teaching in Brussels, and also in a letter to her editor, W S Williams, in which she suggests that women who take on the role of a live-in governess can never be happy.[4] The plight of the governess was one which was drawing considerable social attention at that time. It was virtually the only occupation that was considered respectable for a middle-class woman who had no family to support her, but the experience was often wretched. The governess was neither one of the servants, nor one of the family, and was often treated with contempt by both sides. Anne Brontë writes in vivid detail of these problems in her first novel, Agnes Grey (1847). Jane Eyre is, in comparison, very fortunate in her relationship with Mrs Fairfax, and of course in her romantic relationship with her employer which broke all the rules of social hierarchy.

Passion or self-control?

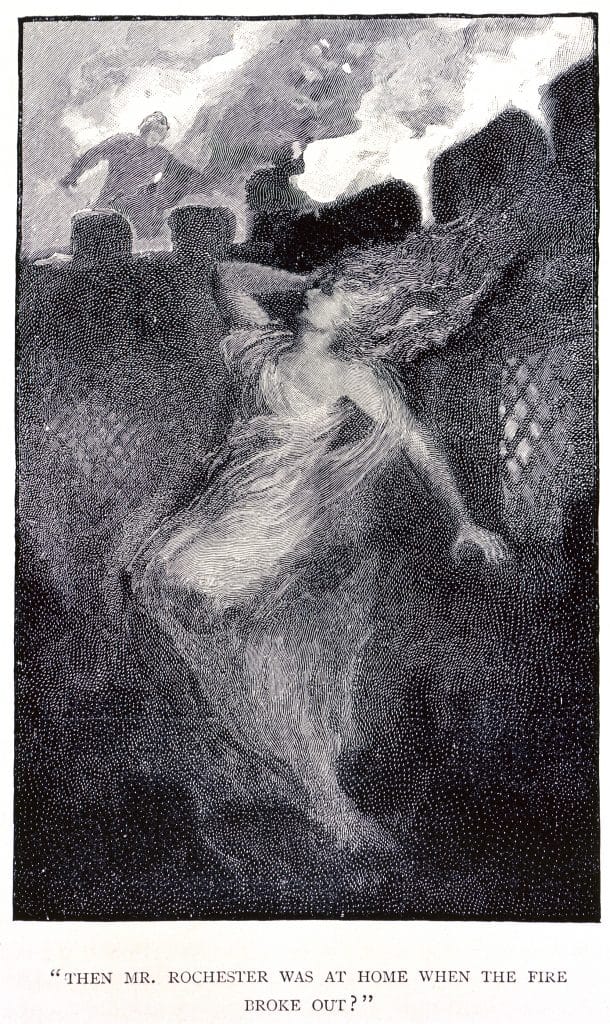

The novel draws a marked implicit contrast between the strong, self-controlled figure of Jane, and the animalistic qualities of Rochester’s first wife, Bertha Mason. But as many critics have shown, there are parallels between the angry child shut in the red room, and the mad wife confined to the attic. Significantly, Jane first sees Bertha in her own mirror, and she refuses to condemn her as Rochester does. The novel was shocking in Rochester’s frank descriptions of Bertha’s sexuality, and his own debauchery, but it is important to note that the novel also depicts Jane as a heroine with strong desires. When Jane is courted by St John Rivers, she fears that if they married, he would ‘scrupulously observe … all the forms of love’ while the spirit was absent: he would offer sex, in other words, without romantic love. Jane feels this would force her ‘to burn inwardly and never utter a cry’ (ch. 34). Images of passion, and of fire, run through the novel, symbolised most forcibly in the fire that burns down Thornfield. Brontë establishes explicit contrasts between Jane and Bertha, but she also suggests that there are underpinning parallels between these two passionate forms of womanhood.

脚注

- See extracts from Quarterly Review, 84 (December 1848).

- An Edition of The Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë, ed. by Christine Alexander, 2 vols. (Oxford : Published for the Shakespeare Head Press by Basil Blackwell, 1986), i, pp.313-4.

- See extracts from Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review, July 1851, pp.289-311; The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, with a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends, ed. by Margaret Smith, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), ii, pp.695-6.

- See extracts from Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review, July 1851, pp.289-311; The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, with a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends, ed. by Margaret Smith, 3 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), ii, pp.695-6.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

撰稿人: Sally Shuttleworth

Sally Shuttleworth is Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford, where she specialises in Victorian literature and the inter-relations of literature and science. Her published works include Charlotte Brontë and Victorian Psychology and The Mind of the Child: Child Development in Literature, Science and Medicine, 1840-1900. She has also published Oxford World’s Classics editions of Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey.