A Thousand and One Nights in England

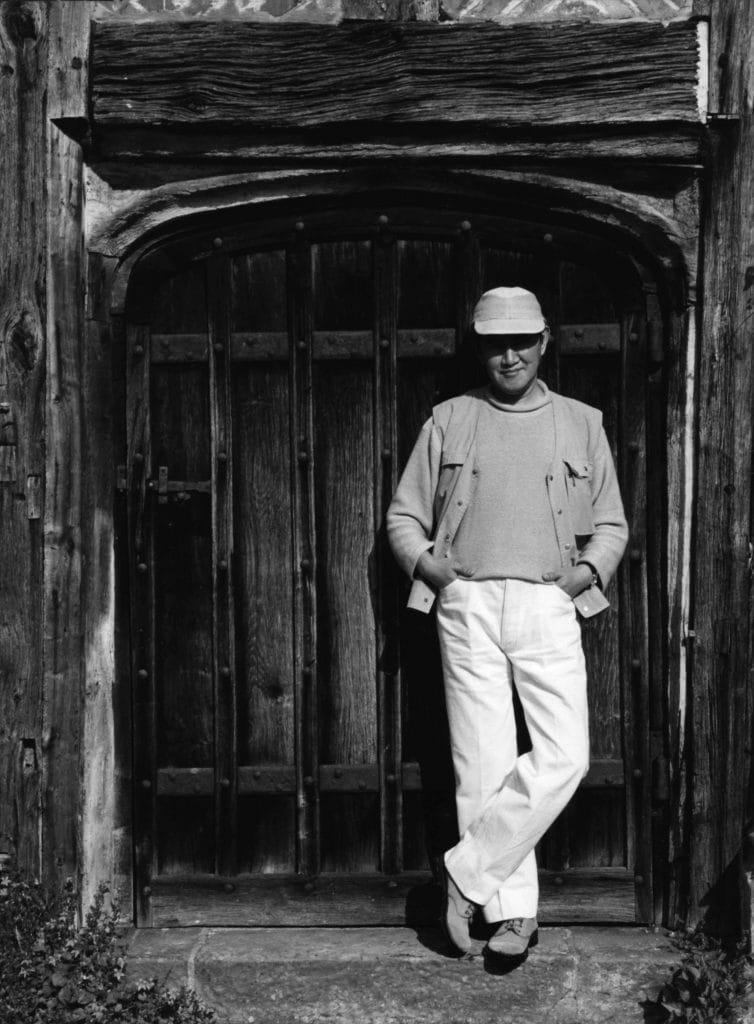

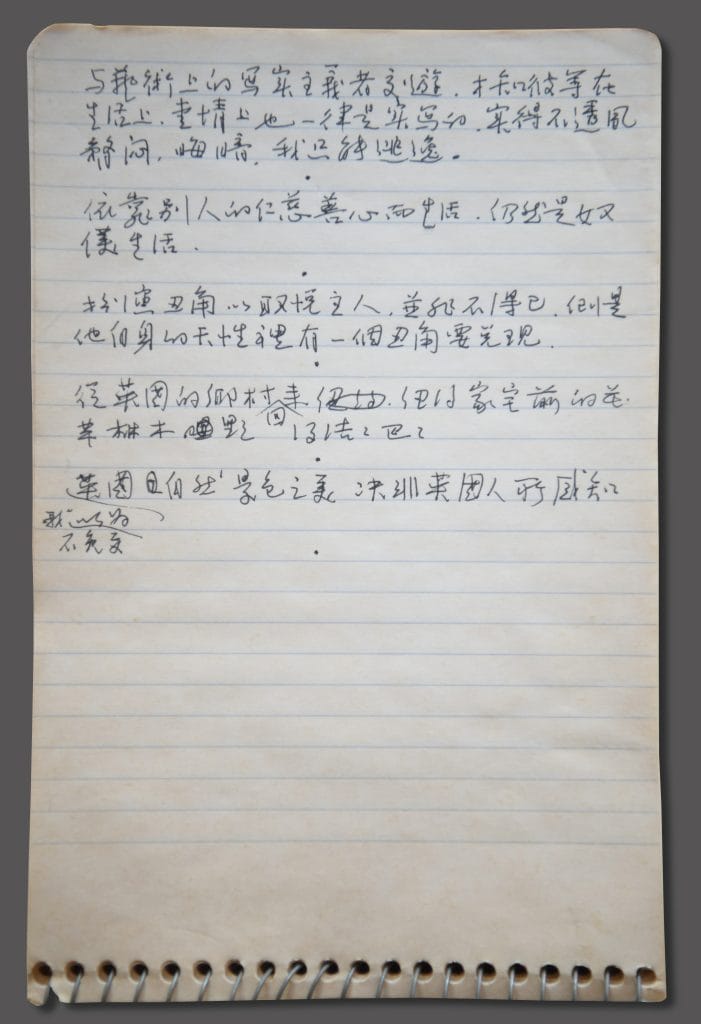

On 6 June 1994, accompanied by his student Chen Danqing, Mu Xin began a three-week visit to England. This was Mu Xin’s only journey across the Atlantic, to which his literary response was ‘A Thousand and One Nights in England’, a draft which remained unfinished.

‘Mu Xin in England’ was recorded by Chen Danqing on a handheld camera, edited by Xie Mengqian. The final part, filmed in black and white, shows Mu Xin strolling through the streets of London on the day he arrived.

© Mu Xin Art Foundation

Prose writing in the name of travel writing is somewhat interesting. To travel in order to write is not. I have read travel writing by the ancients, who all wrote well. As for the travel writing of my contemporaries, mostly they know not how to travel, let alone write.

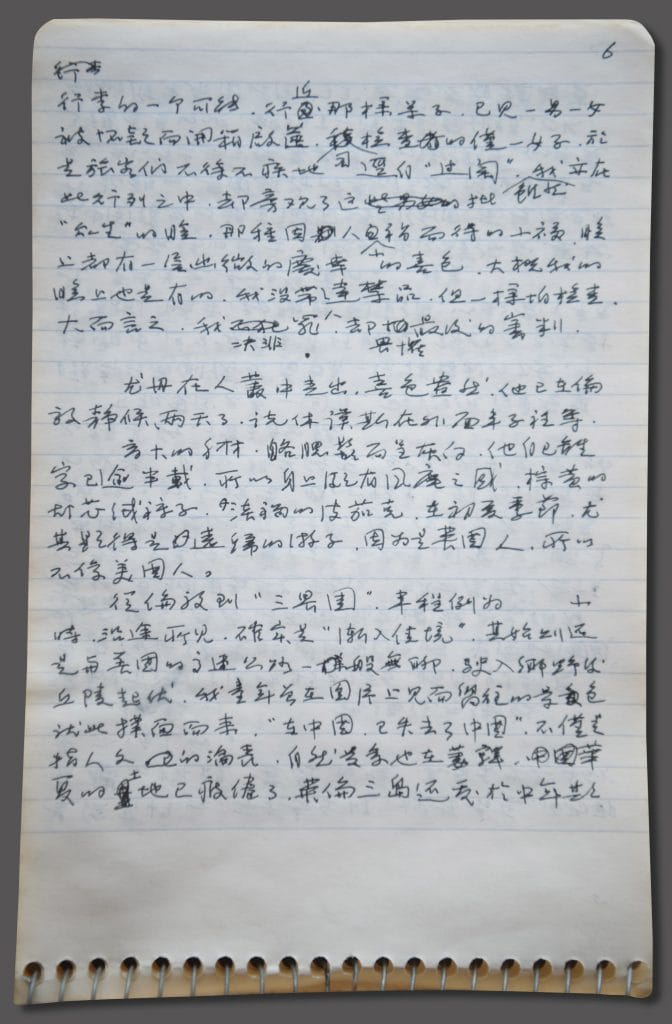

Already it was unexpected that I left China to live in the United States of America. Making the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland my first stop in Europe seems still a faux pas. In my adolescent dream of wandering the world, my first wish was to sail the Red Sea and over the Atlantic Ocean, heading straight for Paris via Marseilles; Britain, Germany, Italy and Greece would follow after a thorough acquaintance with France. Now that, twists and turns upon twists and turns, the dream of my youth is being realised in a roundabout route, I am long benumbed and all romantic remnants are gone. I feel as though I am being ordered to go on business to London. By whose order am I to visit London? Let’s say by that of our oldest ancestors.

In this state of stupor I boarded the charter flight. After years of vegetarian diet, no longer could my stomach take meat. Perchance this analogy hit the nail on the head. I braced myself by making a mental list of my preferred English authors and poets; this incidentally testified that an artist and her origin was not worth a Mass. I had myself become more and more indifferent toward China; a benign kind of indifference, a gentleman’s friendship between an individual and a nation. My gentleman’s friendship with China, one-sided, appeared still more limpid, like water, or a mirror. So this ‘numbness’ was not static but unfolding, at last limpid. It was the case there; it was the case here. So now I felt myself to be a glass of water, or a mirror, gently placed upon the cabin seat, quietly waiting to see London, to see if it would unsettle me.

Those who go to England for the first time, flying with ‘Virgin Airlines’ and are subject to this form of merchant imagination, appear nonetheless hardly flattered. Customarily speaking, deceiving and being deceived are excellent counterparts. A woman whose beauty has faded laments that nobody comes to deceive her anymore. How she would have loved to be deceived. The charm of a consumerist society lies in its omnipresent never-ending deceptions. Merchants are never tired. The difference between humans and other animals is that humans know how to do business, whereas other animals don’t.

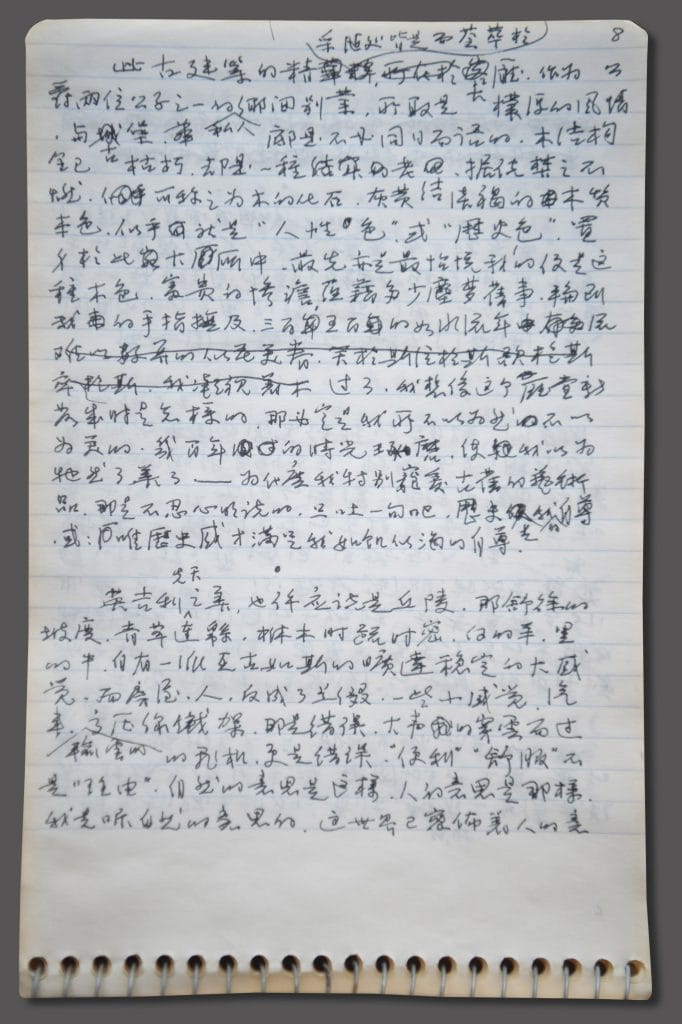

Knowing fine well that I would be eating pizza and drinking Coca-Cola in Shakespeare’s homeland, I am willing to go and take a look. In the past, the drunkard’s interest was not in the wine but in the scenery. Today his interest is in neither the wine nor the scenery, but in himself. Vanity being by nature extrovert, mine is of an introvert kind. Monologue: ‘Aged fourteen I read Romeo and Juliet. Half a century later I stroll around Shakespeare’s home ground.’ Mischievousness is a child’s vanity, the purest and sweetest of vanities. I left my hometown well over fifty years ago; never have I considered going back. Yet I turn around and here I am, in Shakespeare’s neck of the woods. This more than satisfies my vanity.

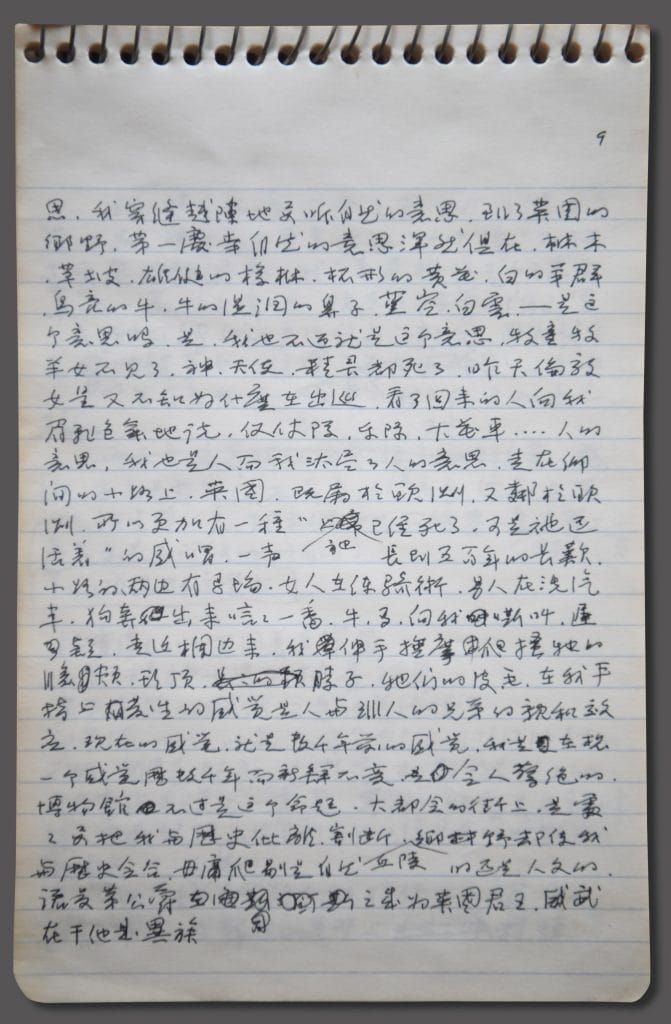

The flight, scheduled to take off at ten fifty-five on the eve of the sixth of June, was half an hour late, possibly due to a thunderstorm. The modern person’s conception of travel is no longer as ruminative or sentimental as that of the ancients. I always say that even if the human race does evolve, each step in its evolution is made at the expense of one in its degeneration. Other creatures are no exception; or rather, precisely because all creatures’ evolution is made at the expense of degeneration, the human race is no exception. The more rapidly modern technology develops, the more rapidly man’s morality dissolves into irrelevance. The airport is bright, clean, fast and convenient; airports all over the world are likewise, and lacking something else. What is it they lack? No one knows what it is exactly. That something will never return. I am the only one to await the return of this ‘something’. Knowing it will not return, I still wait. Such is my fantasy. In reality, I am making something. Instead of waiting in vain, I myself make the ‘it’ as in ‘no one knows what it is’. Wherever is ‘bright, clean, fast and convenient’ is missing something; I walk past, somewhat compensating it for a few minutes, yet taking away again this ‘it’, leaving behind the ‘bright, clean, fast and convenient’ emitting its vague scents of food, vague sounds of music, tax-free cigarettes, alcohol, and travel souvenirs. Souvenirs of what? Of oneself.

The ‘sublime’ in the past was the sea and the desert, hence the abounding images and words relating and appraising the sea and desert. The ‘sublime’ of today is what one sees through the window on an airplane… No more words and images, for delighting in relating the sea and desert belonged to a theist era, contrary to our largely infidel postmodern time. What one sees today during a flight leaves one wordless; gone are myths and illusions. The end of the nineteenth century saw dejection following in the footsteps of elation. In the twentieth century, elation ran its course whilst dejection never came: see my numbness as an example. Still I admit, other than the universe seen through a high-power telescope, the macroworld perceived with the naked eye is doubtless the clouded sky outside an oval airplane window, and the night lights of New York regarded from high above: in ponderous darkness, meanderingly fragmented glittering dots gradually fade and wane. A tragic dream is in the genre of profound music; made into a movie, it would not touch one the same, for the viewer must take an elevated vantage point; it is the bird’s-eye view that registers with me a sense of beauty. The determining factor is of course height, height in turn determined by distance; such height as not experienced by the ancients – I remember always these few minutes each time I fly at night. This is not painterly but musical; it is visual music for its melancholic grandeur, its severe soulfulness. In the world of music I am no stranger.

Heathrow Airport is located in London __. [1] The flight’s descent was particularly quiet, particularly long. As architecture emerged in flocks, the feel of Britain was in sight: houses orderly yet variant, for the most part ochre red, three or four storeys, perfectly reasonable. Skyscrapers in New York literally bicker as though piqued. There are also tall buildings in Britain; the first impression being such, however, I like it, as if rejoicing for something or someone. Anything in its element is for me to rejoice. A thing out of its element is a thing that dies young.

After disembarking I glanced back. The white-bodied, grey-winged Virgin had painted on the sides of its neck a flying maiden holding a fluttering scarf. It really backfired. People in modern times can no longer take symbols or hints; an open book at every turn, they are thus common all over. The vulgar do not appreciate reticence.

Taken to the customs by a shuttle bus, I saw, sure enough, that officers questioned Chinese travellers with extra scrutiny, whilst being exceptionally polite. The government’s predominant worry was with the travellers’ unduly extended stay. We presented the invitation from Mr. Hugh Moss; this seemed to ease the officer’s mind. She recorded a list of things. Okay, now we were in the United Kingdom. There was yet the probability of having our luggage randomly opened and checked. We walked near a desk where a man and a woman had been suspected and ordered to open their cases; a lone officer was examining them. So the rest of the travellers walked unhurriedly through. Being amongst them, I yet observed these mortal beings’ visages, where a faint delight could be universally detected, one of having narrowly escaped a minor misfortune. Conceivably, I too had that expression on my face. Having nothing contraband with me, I feared inspection all the same. Speaking in general terms, I am no criminal, but I dread the Last Judgement.

Liu Dan walked out of a crowd, joy written all over his face. He had been waiting in London for two days; said Mr. Hugh Moss was waiting in his car outside.

Tall and grey-bearded, Hugh Moss himself had been away from home for over half a year, thus looking rather travel-stained. Wearing cinnamon corduroy trousers and a pale brown leather jacket in early summer, he appeared all the more like a voyager coming home from afar. Because he was British, he did not look American.

From London to Moss’s manor was a __-hour drive. [2] Views along the way got progressively better. The start was as dull as highways in the States; into the countryside, hills up and down, scenes I had encountered in pictures as a child kept greeting me. ‘In China, having lost China’ implies not only the bankruptcy of humanities but the decay of nature. The soil of China is tired. The British Isles are only in their middle age; albeit not so youthful as America, albeit weary at times, they have kept their vigorous vitality. The soil of Britain has not withered; its humanities, I am afraid, may have done – this part of the story is to be continued.

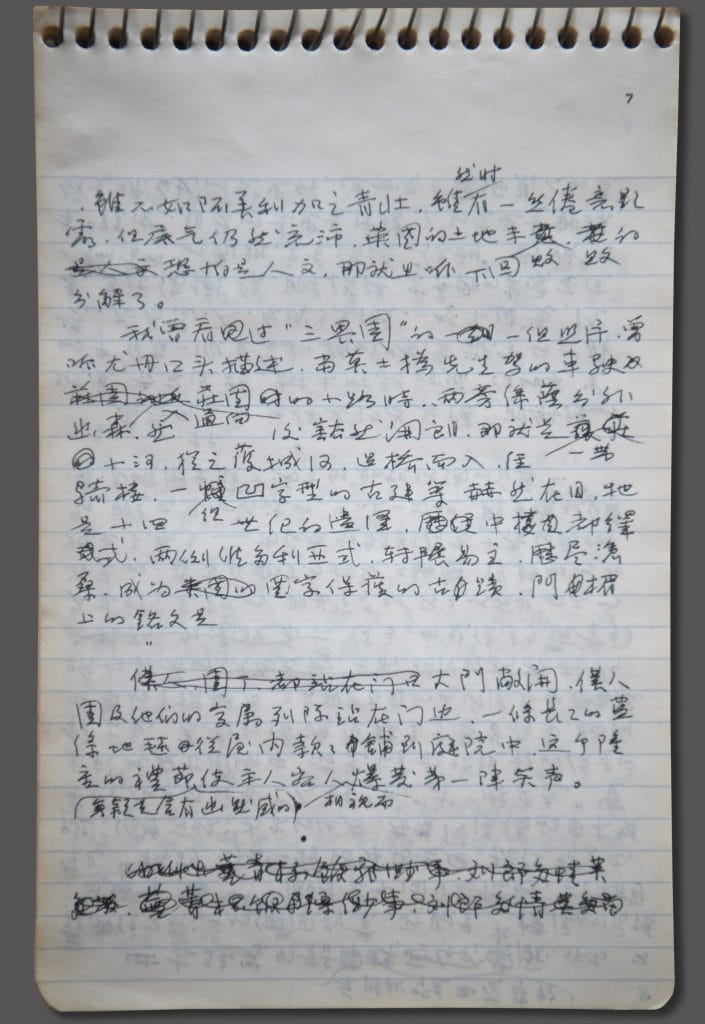

I had seen photographs of the manor and heard Liu Dan describe it. As Moss’s car turned onto a path leading to his home, the greens on both sides, cloistered and profuse, suddenly opened up. We came upon a small river, like a moat. Over the bridge and past the veranda, an assortment of old concave architecture came impressively into sight. Handed down from the fourteenth century, Tudor in the centre and Victorian on the wings, it had changed owners throughout history and was now a listed building. The engraving on the lintel read: ___ [3]

The gate opened. Servants, gardeners and their families stood by. A long blue-green carpet stretched elegantly out into the courtyard. There was certainly humour in this grand ceremony. The hosts and the guests looked at one another, and burst into laughter.

The architecture’s brilliance was everywhere seen, the main hall being its focal point. The private country house of one of the two sons of the Duke of ___, [4] it embodied a plainness of style, distinct from old castles and fancy mansions. The wood structure had deteriorated but not dissipated; apparently it could no longer burn, as if becoming fossils of the wood; now it is greyish brown, the essence of wood’s hue. This seemed to be the hue of humanity, or of history. Standing in this hall, I was first and foremost enchanted by the hue of the wood. Wealth and rank had its own misery, veiled in stories bygone; as I touched it, hundreds of years flew through my fingers. I imagined this hall as it was newly built; I would have no doubt disliked it. After centuries of being sculpted by time, it became what I liked. Why do I favour works of art from antiquity? I cannot bear spelling it out. Let me simply say: history is my self-esteem. Or: only a sense of history appeases my self-esteem, athirst.

England’s innate beauty lies in its hills. Delicate slopes, roaming meadows, trees now dense, now sparse, white sheep and black cows, a feeling of bighearted largeness as if it had been thus since always. Houses and humans seem, on the contrary, embellishments. Cars and high-voltage wire frames are a mistake. Aircrafts going loudly through clouds are still more a mistake. ‘Convenience and comfort’ is no excuse. Nature wishes this, and humans wish that; I listen to nature. This world is filled with the wishes of humans; I look everywhere for nature’s wishes. In the English countryside, I am thrilled that nature’s wishes are all present, all intact: trees, slopes, robust oaks, yellow cup-shaped flowers, fair herds of sheep, jet black cattle, moist noses of oxen, blue sky and white clouds – is this it? Yes, this happens also to be my own wish, no more and no less. Gone are shepherds and shepherdesses. Gone are gods, angels and elves. Yesterday the Queen was out on some occasion in London. Those who saw her reported in jubilation: guard of honour, military band, carriages with flowers… the wishes of humans. I too am human, one with few human wishes left, walking in the countryside. Britain, at once Europe and neighbouring Europe, is all the more ‘dead, but still alive’, a sigh the length of five hundred years. On either side of the little path, there were racetracks; women were practising equestrian skills, and men washing their cars. A dog rushed out to offer solace; cows and horses brayed at me, hesitantly coming toward the fence. I caressed and combed their cheeks, heads, and necks. Their furs and my fingers bonded in an affinity between brothers. This feeling was identical a few millennia ago. I am thinking: that a feeling can go through thousands of years without change is astonishing. This is the theme of museums precisely. On the streets of the Metropolitan, everywhere I am being cut off from history. Hills in the countryside bring history back to me; it matters little whether it be nature or humanities. The Duke of Normandy became the King of England, his might lying in his being foreign.

脚注

Translated by: Dr. Hu Mingyuan

The text in the article is © Mu Xin Art Foundation. It may not be reproduced without permission.

撰稿人: Mu Xin

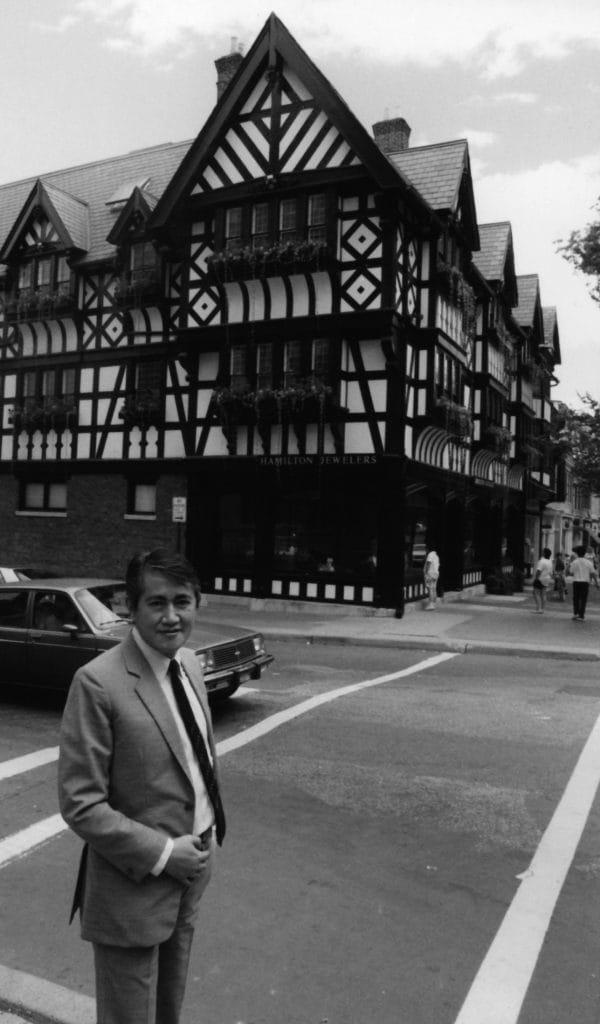

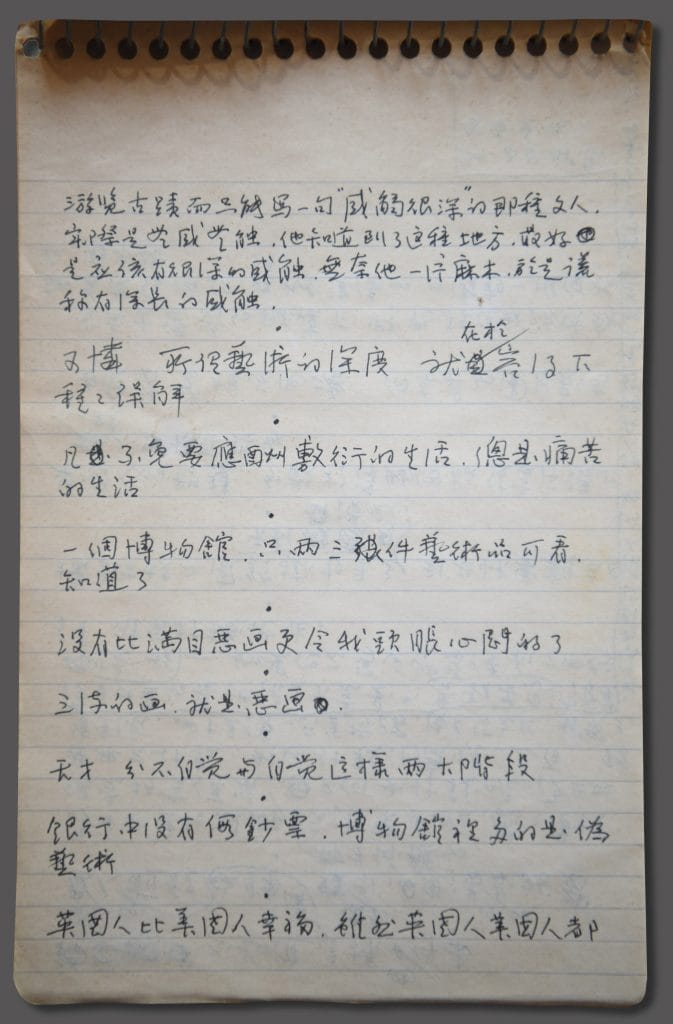

Mu Xin (1927-2011), artist, writer, and poet, was born in Wuzhen, China. He started writing poems at the age of twelve, and at sixteen published an essay in a local newspaper. He later studied at Shanghai Art Academy. In the early 1950s, he taught in a middle school in Shanghai. Between mid-1950s and early 1980s, he was an arts and crafts designer. Twenty volumes of his unpublished writing were confiscated at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), during which he was thrice imprisoned. Whilst in prison, he wrote sixty-six pages of Prison Notes. Exonerated in 1979, he later served as Secretary General of the Arts and Crafts Association before moving in 1982 to New York, where he continued to paint, and began writing again. More than thirty volumes of his poetry and prose essay have since appeared in print on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. In 2001, an exhibition of his painting was held at Yale University Art Gallery before touring to the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, the Honolulu Academy of Arts, and Asia Society Museum in New York. A catalogue of the exhibition, The Art of Mu Xin, was published. In 2006, at the invitation of his hometown, Mu Xin returned to Wuzhen. In 2011, the first English translation of his short stories, An Empty Room, was released in the United States. In 2012, Memoirs of World Literature – notes taken from Mu Xin’s lecture series given between 1989 and 1994 in New York – was published; it became a sensation in both mainland China and Taiwan. In 2017, the first English translation of Mu Xin’s poetry, Toward Bravery, was published in Britain.